Abstract

Background:

Obesity and overweight are the major health problems in Iran. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents living in Zabol settled in Sistan va Baluchistan, one of economically underprivileged provinces in South Eastern of Iran, based on four different definitions.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study was accomplished among a sample of 837 Zaboli adolescents (483 males; 354 females) aged 11-15 years. Anthropometric measurements including weight and height were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Sex-specific BMI-for-age reference data of the Iranian national data, Centers for Disease Control data (CDC 2000), International Obesity Task Force data (IOTF) and recent World Health Organization (WHO) data was used to define overweight and obesity.

Results:

Mean age of the studied population was 13.14 year. Underweight was prevalent among almost 18.7% and 18.4% of adolescents by the use of WHO 2007 and CDC 2000 cut-off points. The prevalence rates reached 25.8% and 27.2% by IOTF and Iranian national criteria, respectively. The highest prevalence of overweight was obtained by IOTF cut-points (10.8%) followed by CDC 2000 criteria (9.4%), WHO 2007 (8.8%) while national Iranian cut-points resulted in the lowest prevalence (2.4%). 7.5% of the studied population were found to be obese by WHO 2007 definition, while this rate was 2.2%, 3.4% and 1.5% by IOTF, CDC 2000 and national Iranian cut-points.

Conclusions:

Almost all definitions revealed coexistence of underweight, overweight, and obesity among Zaboli adolescents. Huge differences exist between different criteria. To understand the best appropriate criteria for Iranian adolescents, future studies should focus on the predictability of obesity-related co-morbidities by these criteria.

Keywords: Adolescents, body mass index, Iran, obesity, overweight, prevalence, Zabol

INTRODUCTION

Underweight and overweight are two spectrums of nutritional disorders that result from under- and over-nutrition, respectively. Due to the experience of nutrition transition in developing countries, these disorders coexist simultaneously in these regions. While overweight and obesity in childhood as a global crisis[1] have been linked to insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, hypertension and coronary artery disease in adulthood,[2] underweight in earlier life has been associated with the incidence of infection,[2,3,4,5] hypertension[6] and obesity in adulthood.[7] About 33% of world adult population were obese in 2005 and the projections for 2030 are that about more than 57% of adult population would be affected.[8]

In Iran, national estimates indicate that almost 16% and 22% of 15-35 years old people are overweight and obese, respectively.[9] Published data about under-nutrition and wasting among Iranian children and adolescents are scant and updated results are present for underprivileged areas.[10] A nationwide study concluded that 17.3% and 17.7% of Iranian school students were underweight and overweight or obese, respectively.[11] Therefore, it seems that Iran faces double burden of disease; a phenomenon that has been known in many other developing countries.

This is particularly important in deprived districts of the country Zabol, a city which is located in Sistan va Baluchestan province, South Eastern of Iran. Compared to other provinces of Iran, Sistan va Baluchistan is more economically underprivileged.[12] Iranian national anthropometrics nutritional indicators survey in 1988 showed that under-nutrition (stunting (34.5%), under-nutrition (22.5%) and wasting (7.5%) is the major problem of this province.[13] Another study done in 2009 showed that the prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity based on Centers for Disease control (CDC) are 16.2%, 8.6% and 1.5% respectively, in adolescent girls living in this province.[12] These rates were calculated using World Health Organization (WHO), First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I), and International Obesity Task Force criteria (IOTF), and were similar to those obtained based CDC criteria.

This study was, therefore, undertaken to estimate the prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity among adolescents in Zabol by the use of an age-specific national[14] and three international references (CDC 2000, WHO 2007 and IOTF).

METHODS

Study population

In this cross-sectional study, 837 adolescent (483 girls and 354 boys) with the mean age of 13.2 years were selected by the use of a clustered random sampling method from adolescents studying in nine Zabol guidance schools.

Data collection and anthropometric measurements

Demographic data about age, parents’ education and occupation was gathered using a questionnaire filled by participants. Weight was measured by a digital scale (Seca, Germany) to the nearest 0.1 kg, without shoes and minimum clothes. Height was measured with a non-stretchable tape meter which was located on a vertical wall to the nearest 0.1 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Definitions

Underweight, overweight, and obesity were defined based on suggested cut-points by four different criteria. We used CDC 2000,[15] recently published cut-points by WHO,[16] and Iranian National cut-points.[14] Based on these cut-points, underweight was defined as those with BMI < 5th percentile, overweight as those with BMI between 85th and 95th percentile and obesity as those with BMI ≥ 95th percentile. Underweight, overweight, and obesity were also defined by the use of IOTF suggested cut-points for BMI in 2000 and 2007.[17,18]

Statistical analysis

Data were processed, summarized and analyzed using SPSS version 15. Prevalence rates and standard deviations were calculated and reported. Demographic differences were searched for by the use of Chi-square test. Furthermore, mean prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity was compared between different criteria using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and difference between each two criteria was examined using Bonferroni post hoc test. P < 0.05 were considered as significant.

RESULTS

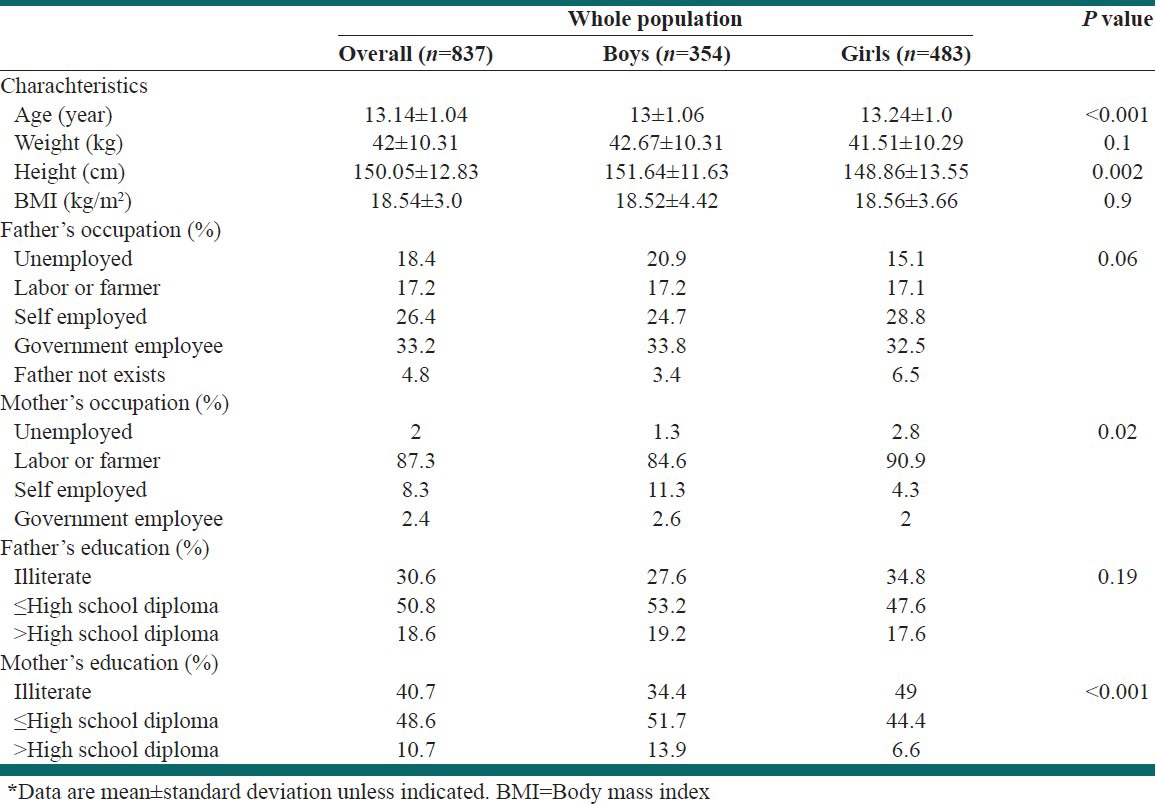

Mean age and its standard error of the studied population was 13.14 ± 1.04 year and mean BMI was 18.5 ± 0.13 kg/m2. In the whole population, girls were significantly older than boys (P < 0.05) while Mean BMI was not significantly different among genders (P = 0.9) [Table 1]. Overall, fathers were mostly government or self-employed and Mothers worked as labor or farmer. Most of fathers in this population had high school diploma or had lower education, and this was true for males too, although this was not true for girls’ mothers, who were mostly illiterate.

Table 1.

General characteristics of Zaboli adolescents*

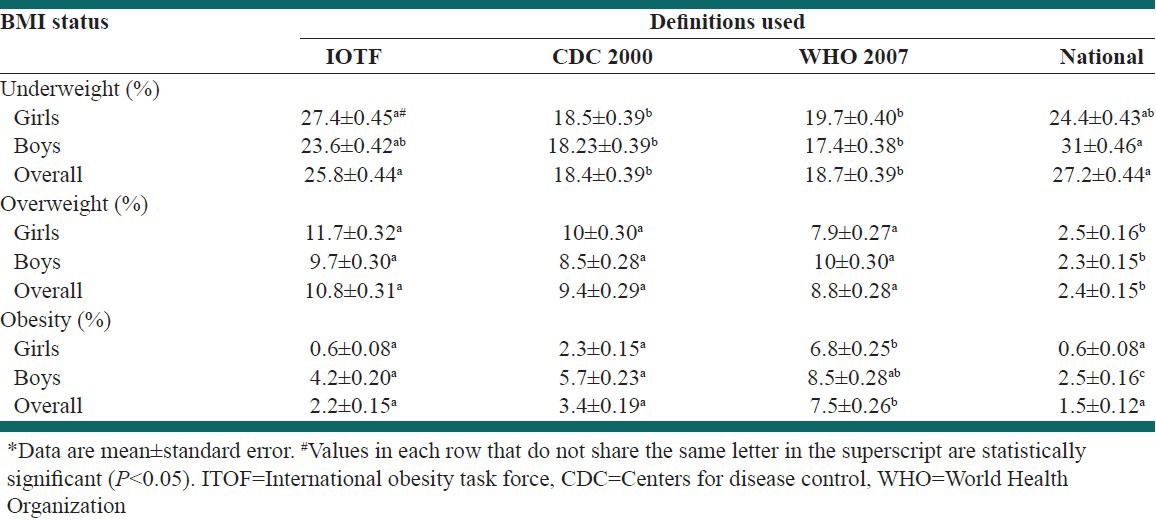

Prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity, separately by sex are indicated in Table 2. Four different criteria were used to obtain prevalence rates. The highest prevalence of underweight was seen by the use of national Iranian cut-off points (27.2%) followed by IOTF cut-off points (25.8%) and their difference was not significant. National criteria indicated that the prevalence of underweight is significantly higher among boys than that in girls (P = 0.03) while this was not true for IOTF criteria (National: 31.8% vs. 25.4%; IOTF: 23.6% vs. 27.6%). The use of both CDC 2000 and WHO 2007 cut-offs revealed a significantly lower prevalence compared to national and IOTF criteria (about 18%) underweight while the prevalence is not statistically significant among genders (CDC 2000: 18.2% vs. 17.5%; WHO 2007: 17.4% vs. 19.7%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity among Zaboli adolescents based on different criteria*

The use of IOTF criteria revealed that over weight is prevalent among 10.8% of adolescents, without any significant difference among genders (9.7% vs. 11.7%) [Table 2]. When we used national, CDC 2000 and WHO 2007 cut-off points, we reached 2.4%, 9.4% and 8.8% prevalence rates of overweight respectively (2.5% vs. 2.3% for national, 8.5% vs. 10% for CDC 2000 and 10% vs. 7.9% for WHO 2007) and males did not have difference in overweight prevalence with females. Using these criteria, overweight did not differ in prevalence among boys and girls while prevalence rate shown by national cut-offs was statistically different compared to other criteria [Table 2].

The highest prevalence of obesity was obtained by the use of WHO 2007 criteria (7.5% for total population) with a significant difference with other cut-offs. Although, Obesity was more prevalent among boys than girls, the difference was not significant (8.5% vs. 6.8%). Obesity was significantly more prevalent in boys than girls based on all other criteria (4.2% vs. 0.6% for IOTF, P < 001; 5.7% vs. 2.3% for IOTF, P = 0.01, and 2.5% vs. 0.6% for National, P = 0.02).

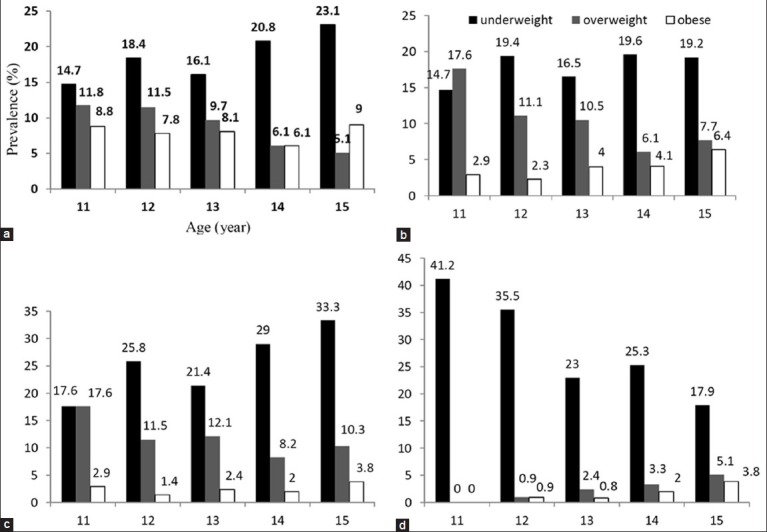

Figure 1a presents the age categorized prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity based on WHO cut-offs. As shown the prevalence of underweight was highest among 15 years old (23.1%) while overweight and obesity was mostly prevalent in 11 year adolescents (11.8% and 8.8% respectively). For CDC 2000 cut-offs [Figure 1b], underweight, overweight, and obesity had the highest prevalence in 14 year (19.6%), 11 year (17.6) and 14 year (4.1%) adolescents, respectively. Considering IOTF cut-offs [Figure 1c], highest prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity was among 15 (33.3%), 11 (17.6%) and 15 year (3.8%) adolescents while for National cut-offs [Figure 1d] the prevalence was highest among 11 year (41.2%), 15 year (5.1%) and 15 year (3.8%) adolescents, respectively.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity based on age using world health organization (a) Centers for disease control (b) International obesity task force (c) and National (d) Criteria

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicated that underweight is prevalent among almost 18.4% and 18.7% of Zaboli adolescents by the use of CDC 2000 and WHO 2007 cut-off points, respectively. The prevalence rates reached 25.8% and 27.2% by IOTF and Iranian national criteria, respectively. The highest prevalence of overweight was obtained by IOTF cut-points (10.8%) followed by CDC 2000 criteria (9.4%), while WHO 2007 and national Iranian cut-points resulted in 8.8% and 2.4% respectively. 7.5% of the studied population were found to be obese by WHO 2007 definition, while this rate was 3.4%, 2.2% and 1.5% by CDC 2000, IOTF and national Iranian cut-points, respectively. Our analysis also showed that IOTF and National criteria reveal significantly higher prevalence of underweight, while national criteria shows a significantly lower rates of overweight, while WHO 2007 tend to approximate higher rates of obesity compared to other criteria in this sample.

Last published report on this region of Iran (Sistan va Baluchistan province), slides back to 2009, by Montazerifar et al.,[12] in which they stated that prevalence of underweight is 16.2% and 10.1% based on CDC and WHO criteria respectively. The prevalence of overweight was reported to be 8.6%, 8.8% and 8.4% using CDC, IOTF and WHO criteria respectively while obesity prevalence was similar based on all mentioned criteria and was reported as 1.5%. In comparison to our results, the prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity is increased, and this raise is tangible particularly for underweight. This shows that underweight is still the major nutritional problem in adolescents living in that district of Iran, while overweight and obesity are becoming more prevalent too, showing that double burden of malnutrition is becoming a problem and implementing a preventive strategies are necessary.

While underweight has its own negative consequences on health and quality of life,[2,3,4,5,6,7] overweight, and obesity has long been considered as a predisposing factor that affects individual's health. Yet, the importance of obesity and overweight among children has not been accentuated as much until recently.[19] Overweight children and adolescents are at greater risk of being overweight as adults, and adults who are overweight are at higher risk of numerous health problems including hypertension, coronary heart disease, gallbladder disease, non-insulin dependent diabetes, and some cancers.[20] In Iran, an increasing trend in the prevalence of obesity has recently been documented in youth,[21] and adults.[9] Furthermore, it has been reported that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Iranian children is comparable to those in western societies.[22] A high prevalence of the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype among Iranian children has also been documented,[23] which could make them to cluster metabolic abnormalities. Therefore, childhood obesity is a major crisis in Iran that should be taken into account by health sector to use a preventive approach in this regard.

There is a lack of agreement about the definition of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence,[24] and the absence of a universal definition has led to inability to monitor the worldwide development of childhood obesity. Distribution-based cut-off values, such as 85th and 95th percentiles of BMI has been proposed and used most often in literature.[23] WHO has released the updated cut-off points for percentiles of BMI in 2007. In May 2000, the IOTF Childhood Obesity Working Group published standard definitions for overweight and obesity in childhood.[17] These cut-off points were, however, not chosen on the basis of their empirical relation to risk factors; rather, they were derived by identifying age- and sex-specific BMI values corresponding to cut-offs for overweight (BMI = 25) or obesity (BMI = 30) in adults. The results of previous reports from Iran and other Middle Eastern countries,[25] have always been difficult to interpret as they have relied on different definitions and until now there is no report on the prevalence of overweight comparing Iranian national cut-points with those of WHO 2007, CDC 2000 and IOTF in children and adolescents; the Dorosty et al. study, however, did compare Iranian national reference cut-points with those of IOTF but this was done only in children aged 2-5 years residing in rural provinces of Iran.[21] Therefore, the information provided by this study shed light to some extent on the magnitude of the problem based on different definitions.

Our findings reflect the difference in prevalence estimates based on different definitions. In the whole population, estimates of underweight obtained from CDC 2000 cut-points were lower than those obtained by using National or IOTF, while no significant difference in the estimates was found between CDC 2000 cut-points and WHO 2007 cut-offs. Getting back to the prevalence of overweight and obesity, estimates obtained by the use of Iranian cut-points were lower than those found by CDC 2000, IOTF and WHO 2007 cut-offs. Other investigators have also showed a discrepancy in estimates based on different criteria in other countries. Kuczmarski et al. showed that prevalence of overweight and obesity are always lower with IOTF criteria than the national criteria, even in USA.[26] Reilly et al. showed that IOTF criteria lead to a greater underestimation in boys.[27] Dororsty et al. showed that the prevalence of overweight by using IOTF cut-points was significantly higher in the 2-3 years Iranian children than when using Iranian cut-points.[21] However, we have no children aged 2-3 years in the present study. The recently recommended cut-off points for BMI in Iranian children have provided us the opportunity to identify prevalence based on national criteria. Our study gives appropriate data against which estimates from other studies in Middle Eastern countries and elsewhere can be compared with the same methodology.

The double burden of disease we found in the current study is not unique for Iranian children. Among Turkish adolescent girls, the prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity have been reported to be 11.1%, 10.6% and 2.1%, respectively.[28] In a similar study in Qatari adolescent girls, the rates were 5.8%, 18.9% and 4.7%, respectively.[29] The prevalence of underweight among Chinese youngsters aged 15-20 was has been reported to be 35.9.[30] Therefore, despite the rising trend of obesity worldwide, problems of malnutrition and nutrient deficiencies still dominate the public health nutrition agenda in our area.

This study has several strengths. First, using a population representative sample of Zabol, we found the coexisting high prevalence of underweight and overweight in Iranian population of children and adolescents. Second, the lack of definition-based comparative studies from this part of the world makes our study findings interesting.

Our participants were selected only from Zabol one of the big cities of Sistan va Baluchistn province, while the situation may be different particularly in rural areas. Studies with bigger sample size which cover both urban and rural areas of this economically deprived province are recommended.

CONCLUSIONS

This study indicates the coexisting high prevalence of underweight and overweight among guidance-school students of Zahedan, Iran. Because nutritional patterns and physical activity behaviors develop during childhood, preventive approaches addressing children and adolescents are required to deal with the problem of underweight, overweight, and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

All authors were involved in planning the study design. Ahmad Esmaillzadeh and Amin Salehi- Abargouei are involved in conception of the study hypothesis. Anthropometric measurements were supervised by Hadi Abdollahzad and Zoleykhah Bameri. The data analysis was performed by Amin Salehi-Abargouei and supervised by Ahmad Esmaillzadeh. Amin Salehi-Abargouei and Ahmad Esmaillzadeh wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in revisions and final approval of the manuscript. None of the authors had any financial or personal conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Karnik S, Kanekar A. Childhood obesity: A global public health crisis. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramachandran P, Gopalan HS. Undernutrition and risk of infections in preschool children. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:579–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeremiah ZA, Uko EK. Childhood asymptomatic malaria and nutritional status among Port Harcourt children. East Afr J Public Health. 2007;4:55–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raja’a YA, Mubarak JS. Intestinal parasitosis and nutritional status in schoolchildren of Sahar district, Yemen. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:S189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kossmann J, Nestel P, Herrera MG, El Amin A, Fawzi WW. Undernutrition in relation to childhood infections: A prospective study in the Sudan. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:463–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawaya AL, Sesso R, Florêncio TM, Fernandes MT, Martins PA. Association between chronic undernutrition and hypertension. Matern Child Nutr. 2005;1:155–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2005.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikki N, Abdul-Rahim HF, Awartani F, Holmboe-Ottesen G. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of stunting, underweight, and overweight among Palestinian school adolescents (13-15 years) in two major governorates in the West Bank. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1431–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rashidi A, Mohammadpour-Ahranjani B, Vafa MR, Karandish M. Prevalence of obesity in Iran. Obes Rev. 2005;6:191–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddah M, Shahraki T, Shahraki M. Underweight and overweight among children in Zahedan, south-east Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:1519–21. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelishadi R, Heshmat R, Motlagh ME, Majdzadeh R, Keramatian K, Qorbani M, et al. Methodology and early findings of the third survey of CASPIAN study: A national school-based surveillance of students’ high risk behaviors. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:394–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montazerifar F, Karajibani M, Rakhshani F, Hashemi M. Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity among high-school girls in Sistan va Baluchistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:1293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tehran: Islamic Republic of Iran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education and the United Nations Children's Fund; 1998. Nutritional status of children in the province of Iran: Anthropometrics nutritional indicators survey (ANIS) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosseini M, Carpenter RG, Mohammad K, Jones ME. Standardized percentile curves of body mass index of Iranian children compared to the US population reference. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:783–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2002:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World health organization. The WHO Child Growth Standards. 2011. [Last cited May 2011, Last accessed February 2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en .

- 17.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: International survey. BMJ. 2007;335:194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39238.399444.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradford NF. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. Prim Care. 2009;36:319–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubenstein AH. Obesity: A modern epidemic. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2005;116:103–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorosty AR, Siassi F, Reilly JJ. Obesity in Iranian children. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:388–91. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azadbakht L, Etemadi A, Azizi F. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Iranian adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:377–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azadbakht L, Azizi F. Prevalence of the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype in Iranian adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jebb SA, Rennie KL, Cole TJ. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among young people in Great Britain. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:461–5. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:62–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Wei R, Kuczmarski RL, Johnson CL. Prevalence of overweight in US children: Comparison of US growth charts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with other reference values for body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:1086–93. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reilly JJ, Dorosty AR, Emmett PM Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood Study Team. Identification of the obese child: Adequacy of the body mass index for clinical practice and epidemiology. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1623–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oner N, Vatansever U, Sari A, Ekuklu E, Güzel A, Karasalihoğlu S, et al. Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in Turkish adolescents. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134:529–33. doi: 10.57187/smw.2004.10740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bener A. Prevalence of obesity, overweight, and underweight in Qatari adolescents. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:39–45. doi: 10.1177/156482650602700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko GT, Tang JS. Prevalence of obesity, overweight and underweight in a Hong Kong community: The United Christian Nethersole Community Health Service (UCNCHS) primary health care program 1996-1997. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15:236–41. 30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]