Abstract

Highly curved bilayer lipid membranes make up the shell of many intra- and extracellular compartments, including organelles and vesicles. Using all-atom molecular dynamics simulations, we show that increasing the density of lipids in the bilayer membrane can induce the membrane to form a curved shape.

Membranes define the intra- from extracellular environment and compartmentalize the interior of the cell. Dynamic changes in membranes, such as budding, fission, and fusion, occur via alterations of membrane shape and curvature. The shape of the membrane is driven by a combination of lipid composition, transmembrane and surface proteins, as well as forces from the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix.1, 2 The molecular shape of the lipids in a membrane dictate the membrane’s spontaneous curvature. For example, lysophospholipids, which have a large hydrophilic head group and small hydrophilic tail, form highly curved membrane structures.3 In the cell, lipid flippases move lipids between the two leaflets of the bilayer, creating asymmetric distributions that can also cause the membrane to spontaneously form a curved shape.4 The asymmetry between the two leaflets can be in absolute number of lipids or distributions of different lipid head groups.5, 6

Both transmembrane and membrane surface proteins can induce a flat membrane to form more complex shapes.7–12 The confinement of the cell membrane by a solid support, such as the extracellular matrix or cytoskeleton in the cell, restricts how the membrane can deform when subjected to perturbing forces.1 The physical interplay between membrane and membrane protein is not unidirectional. For example, embedding a mechanosensitive transmembrane protein in a curved membrane can alter the structure of that protein.13

Computational simulations provide a powerful tool to study membrane biophysics. The atomistic detail and temporal resolution available through simulations has made them a useful tool for investigating the dynamics of lipid membranes.14, 15 Membranes of different organelles and vesicles require different representations in simulations; i.e. lipid composition and membrane shape both need to be considered.

Most eukaryotic cells have diameters > 8 µm.16 Typical computational simulations of the plasma membrane use a simulation box size on the scale of tens of nanometers and model the membrane as a planar surface with no defined curvature. This approximation is reasonable because on the scale that the membrane is being modeled, curvature does not have an appreciable effect on lipid organization or membrane shape. For example, a 100×100 nm2 square plasma membrane represents only ~0.001% of the surface area of an 8 µm cell. Nonetheless, many membrane-bound compartments found either within or released by cells are submicroscopic in size. For example, exosomes—released into the extracellular environment by cells and thought to be mediators of intracellular communication—are highly curved vesicles 30–100 nm in diameter (curvature is defined as the reciprocal of the radius).17 In this case, a 100×100 nm2 membrane could represent as much as ~90% of an exosomal membrane surface area. In simulations modeling the bilayer membrane of submicroscopic particles such as exosomes, consideration of the effects of curvature on the shape of the membrane and lipid packing and ordering has the potential to more accurately represent the membrane and elucidate more biologically relevant lipid/protein interactions.

Using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we describe here a method of inducing membrane curvature by increasing the density of lipids in a model bilayer membrane. The bilayer membrane was composed of 500 lipids (250 per leaflet) and was a mixture of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylserine (POPS). This lipid composition was chosen to approximately represent the charge distribution of a cellular membrane.18 The POPS composition was varied between 0%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% of the total lipids. Variations in POPS concentration were introduced to explore whether changing the concentration of a negatively charged head group has an effect on the curvature of the model bilayers. Two independent simulations for each POPS concentration were performed. Initially, flat bilayers of these lipid mixtures were simulated using reported equilibrium lipid surface area values of POPC and POPS.19 Curvature was induced by scaling the x and y coordinates of the system. The z coordinate was kept coupled to a pressure reservoir to maintain the pressure, which ensures very slight changes in the height of the box during the course of the simulation. The lateral area of the simulation box was maintained for both the flat and curved bilayer simulations. That is, every time there is a scaling of coordinates, the size of the primary simulation box is also changed so differently scaled systems have the same lateral area.

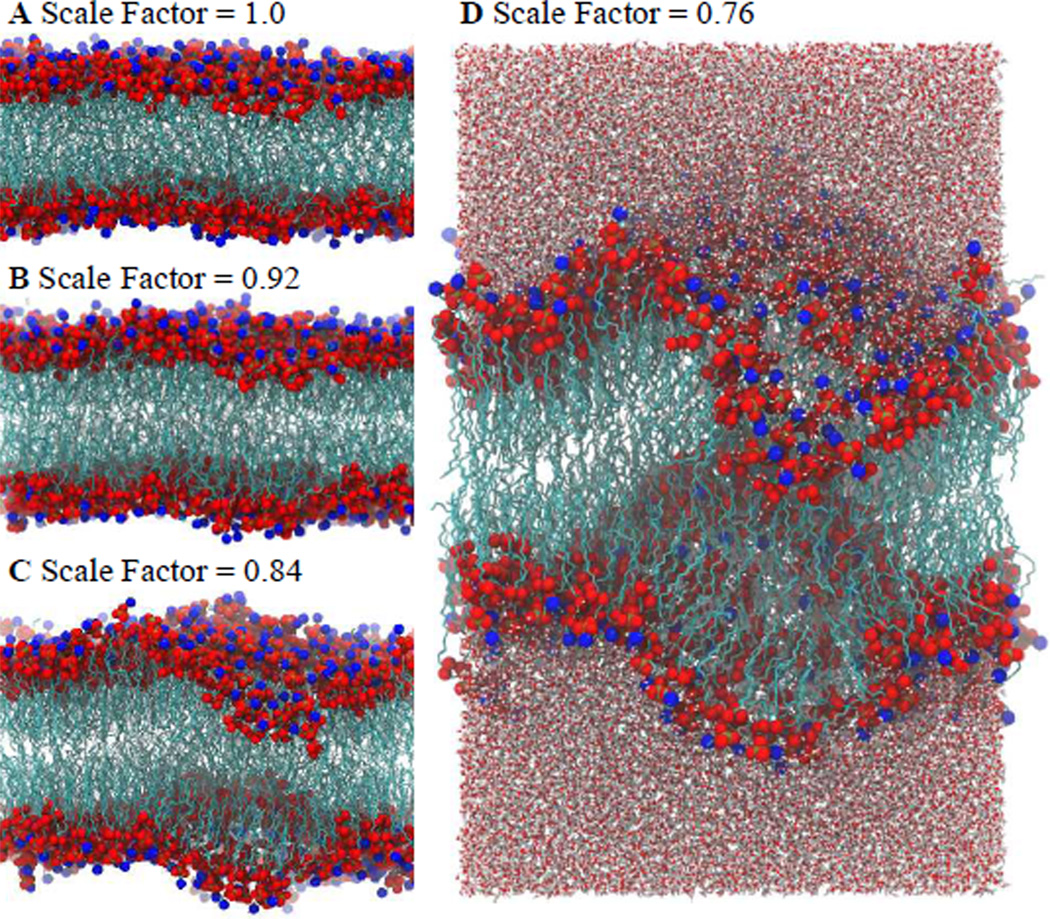

The scaling procedure involves a gradual compression of equilibrated flat bilayers. After equilibrating the flat membranes for 2 ns, the x and y coordinates of the systems were scaled by 2% (creating a 0.98 scale factor after the initial compression). This scaling of coordinates has the effect of moving the system components towards the center of the simulation box, increasing the density of the lipids. Likewise, the size of the simulation box was also scaled accordingly to maintain the density of the system. The system then underwent an energy minimization followed by a short dynamics run of 5 ps. These steps were repeated—scaling, energy minimization, and short dynamics—successively until the resulting system reached a scale factor of 0.70 relative to the original box size. Snapshots of the resulting structures are shown in Fig. 1. As can be seen, even after only 5 ps of dynamics, curvature of the membrane can be readily observed. Representative videos showing the compression process are included in the Supplementary Information (Video S1, S2, and S3).

Fig. 1.

(A–C) Side views of the bilayer membranes showing increased curvature formation with increasing compression (no compression, scale factor = 1.0). Phosphate atoms are shown in red, nitrogen atoms in blue, and lipid hydrocarbon tails in teal. Waters are not shown for clarity. (D) Side view showing the entire simulation box including waters.

The selected structures resulting from these short, iterative scaling processes were then allowed to further evolve for an additional 4 ns simulation. The systems scaled to 0.84, 0.80, and 0.76 (labelled as sc0.84, sc0.80 and sc0.76) were chosen for further MD simulations. In total, 30 independent bilayer systems were simulated each of which responded to compression similar to that shown in Videos S1, S2 and S3, showing curvature as a response to lateral compression. Characteristics of the simulated systems are summarized in Table S1 (Supplementary Information). Further details on the MD simulations can be also found in the Supplementary Information. The systems with 15% POPS were simulated for a total of approximately 10 ns and the time series of the radius of curvature is shown in Fig. S1. Here it can be observed that there are no major transitions occurring after ~2.5 ns. Figure S2 shows the time series of the radius of curvature from the beginning of compression, showing the drop in the radius as curvature is induced and maintained.

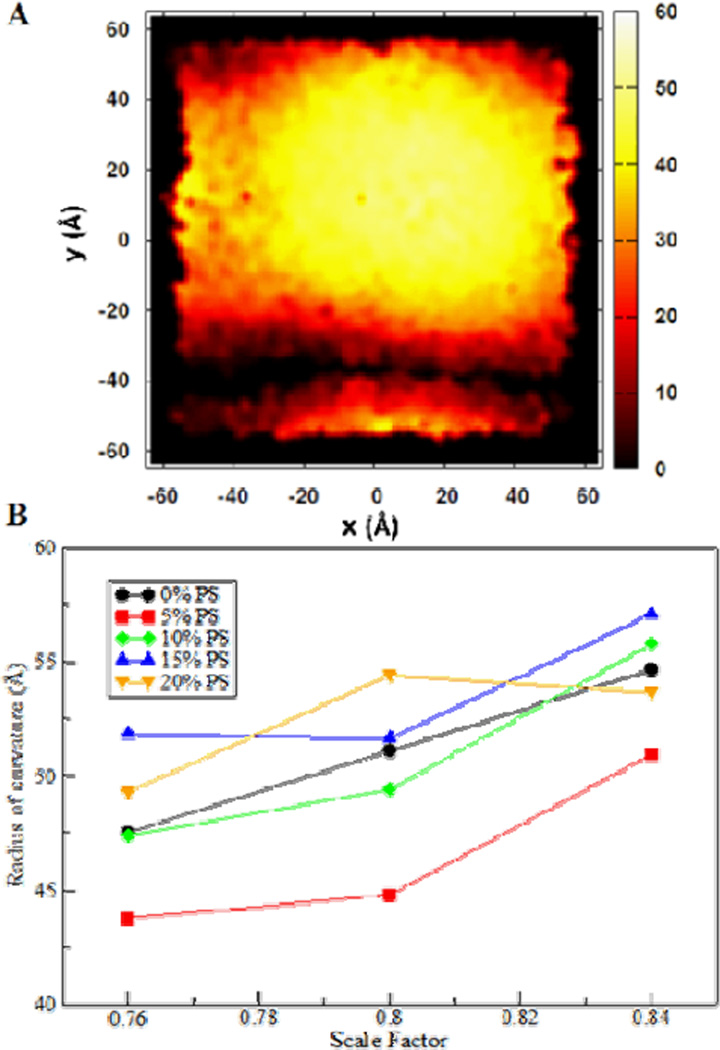

To characterize the compressed bilayers, a single value was used to describe the bilayer curvature in the primary simulation box. In particular, we chose the leaflet that represents the convex or exterior side of the membrane. Computing the radius of the localized curvature found in the primary simulation box involves extracting coordinates of the phosphorus atoms from the simulation trajectories. From these, a distribution of z-coordinates can be constructed along an x-y surface. A sample distribution is shown in Fig. 2A. The crest of the resulting distribution, via periodic boundary conditions, was centered within the primary simulation box. The distribution, containing the average P atom positions over 3 ns, is then fitted to a sphere to obtain a radius of curvature. Fig. 2B shows the membrane curvature measures for the different simulated systems. It is expected that the smaller the scaling factor, or more compressed the system is, the more the resulting membrane would be curved. This trend is clearly demonstrated in Fig. 2B. Except for the sc0.84/sc0.80 scaled bilayers of the 20% POPS systems, it can be observed that the curvature increases with increased compression of the system. The anomalous points are perhaps due to insufficient equilibrium in a ~ns timescale.

Fig. 2.

Quantification of membrane curvature. (A) Top view of averaged 15% POPS sc0.80 system coordinates. Coordinates in the z dimensions are represented by color. The color scale in Å is shown at the right. (B) Radii of curvature of the different lipid bilayer systems compressed by scaling the x and y coordinates (no compression, scale factor = 1.0). The labels refer to the concentration of POPS in the bilayer. Each point represents the average of two separate scaling and simulation dynamics.

The range of curvature radii obtained in this study is in good agreement with the literature reports.7, 20 Such range of curvature values obtained indicate that, for the systems used in this study, the scaling factors 76% to 84% may be used to produce bilayers to model exosomes that are sensed by curvature-binding peptides or proteins (e.g. the MARCKS-ED peptide).21

As shown in Fig. S1 and by the movies (Video. S1, S2 and S3), after undergoing the lateral compression procedure, the induced curvatures in the different bilayer systems do not disappear. Importantly, these results further emphasize that the compressed membrane bilayers are not metastable and are not likely to return to a flat state. As can also be observed from the movies, the chains are not aligning to transition to the gel phase but appear to stay in the fluid phase, which is estimated to be more stable than the gel phase by ~1 kJ/mole at 10 K above the phase transition temperature.

It can also be observed from Fig. 2 that the effect of varying the concentration of POPS is not well defined. At high POPS concentrations, we initially expected that there should be considerable electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged POPS lipid head groups that would lead to greater membrane curvature. The lack of a clear result may be at least in part due to insufficient equilibrium or another yet to be explained phenomenon. Increased simulation time could potentially answer this question, but with an excess of 150,000 atoms in these simulations, such studies would be quite computationally expensive. As a comparison, the simulations presented in this paper represent in excess of 2 million processor hours. We leave the question of the effect POPS lipid composition on membrane curvature open for future investigation.

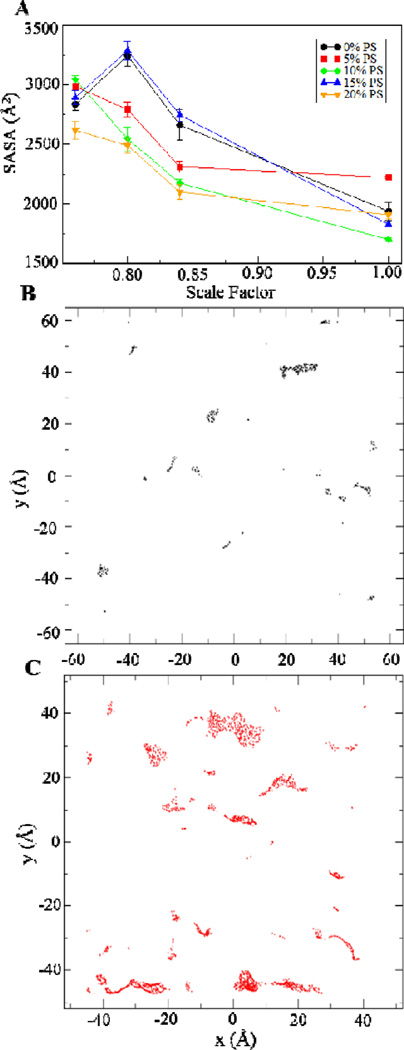

One effect that curvature can be expected to produce in a membrane is defects in the convex surface of a curved bilayer.21, 22 The presence of defects on the surfaces of curved membranes has been suggested to be important in curved bilayer-protein interactions.20. As a measure of the defects produced, the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) was determined for the convex surface of the curved bilayer using a solvent probe approximating the size of a water molecule. Fig. 3 shows the SASA for the different curved bilayers simulated. Except for the sc0.80 scaled bilayers of the 0% and 15% POPS systems, it can be observed that as the bilayer becomes more curved, the SASA also increases. Following the previously reported method by Cui and co-workers, defects determined via SASA calculations were mapped onto a 2D grid.22 Representative defect maps from a single trajectory frame of the 0% PS system are shown in Figs. 3B and C. These figures likewise show the presence of more defects on the curved system. These results indicate that the simulated systems can provide the characteristic surface defects of curved membranes and thus, can be used for in silico studies of biologically relevant curved bilayer-protein interactions. As with the radius of curvature, the concentration of POPS does not appear to have a consistent effect on the extent of surface defect production.

Fig. 3.

Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of the convex surface of the compressed bilayer systems. (A). Average SASA values. The labels refer to the concentration of POPS in the bilayer. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. (B and C). 2D map of defect locations across the surface of a flat (B) and curved (C) bilayer.

The biological role of submicroscopic particles, such as exosomes, is increasingly of interest. A main characteristic of these particles is a high degree membrane curvature. Through the use of MD simulations, we have devised a method for inducing curvature in lipid bilayers that can be used to investigate highly curved bilayers. Our method induces curvature by increasing the density of lipids through compression of the simulation box. We have found that curvature can be induced relatively quickly (within 5 ps) in model bilayer systems. The degree of curvature of the bilayer is found to increase with elevated lipid density. Cellular processes such budding off of highly curved vesicles are likely to give rise to extremely curved regions which could be modelled by the range of curvatures observed in this work. Such range of curvatures are also observed in computational studies of tubulation7 and buckled bilayers20. Curvatures with greater radii may be induced in larger bilayers. For a fully atomistic study such described in this work, this will greatly add to the computational expense and thus, we leave the investigation of larger bilayers for future investigation. The amount of surface defects produced by membrane curvature also increases with lipid density. The bilayer membranes produced by this method can be used as models to study lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions in highly curved bilayers, providing a useful tool to investigate biologic processes that involve dynamic changes in membrane shape.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Science Foundation (CHE 0954819) and the National Institutes of Health (GM 103843) for financial supports. NK gratefully acknowledges the support of NIH MSTP training grant T32 GM008497. This work utilized the Janus supercomputer, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (award number CNS-0821794) and the University of Colorado Boulder. The Janus supercomputer is a joint effort of the University of Colorado Boulder, the University of Colorado Denver and the National Center for Atmospheric Research. We also thank Prof. Edward Lyman of the University of Delaware for the defect mapping protocol and Peter Tieleman of the University of Calgary and James Kindt of Emory University for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Additional details on the method and system characteristics are provided. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Staykova M, Holmes DP, Read C, Stone HA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:9084–9088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102358108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller N, Rand RP. Biophys. J. 2001;81:243–254. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75695-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devaux PF, Herrmann A, Ohlwein N, Kozlov MM. BBA-Biomembranes. 2008;1778:1591–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daleke DL. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:821–825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markvoort AJ, van Santen RA, Hilbers PA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:22780–22785. doi: 10.1021/jp064888a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin Y, Arkhipov A, Schulten K. Structure. 2009;17:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arkhipov A, Yin Y, Schulten K. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2806–2821. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyman E, Cui HS, Voth GA. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1783–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui HS, Ayton GS, Voth GA. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2746–2753. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsin J, Gumbart J, Trabuco LG, Villa E, Qian P, Hunter CN, Schulten K. Biophys. J. 2009;97:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blood PD, Voth GA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:15068–15072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603917103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer GR, Gullingsrud J, Schulten K, Martinac B. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1630–1637. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.080721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo J, Cui Q. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2267–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandt C, Ash WL, Tieleman DP. Methods. 2007;41:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gyorgy B, Szabo TG, Pasztoi M, Pal Z, Misjak P, Aradi B, Laszlo V, Pallinger E, Pap E, Kittel A, Nagy G, Falus A, Buzas EI. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68:2667–2688. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denzer K, Kleijmeer MJ, Heijnen HFG, Stoorvogel W, Geuze HJ. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:3365–3374. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman JE, Lenard J. Science. 1977;195:743–753. doi: 10.1126/science.402030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jo S, Lim JB, Klauda JB, Im W. Biophys. J. 2009;97:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang H, de Joannis J, Jiang Y, Gaulding JC, Albrecht B, Yin F, Khanna K, Kindt JT. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2647–2657. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton LA, Yang HW, Saludes JP, Fiorini Z, Beninson L, Chapman ER, Fleshner M, Xue D, Yin H. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:218–225. doi: 10.1021/cb300429e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui HS, Lyman E, Voth GA. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.