Abstract

Objectives

For healthy women at high risk of developing breast cancer, a bilateral mastectomy can reduce future risk. For women who already have unilateral breast cancer, removing the contralateral healthy breast is more difficult to justify. We examined trends in the number of women who had a bilateral mastectomy in England between 2002 and 2011.

Design

Retrospective cohort study using the Hospital Episode Statistics database.

Setting

NHS hospital trusts in England.

Participants

Women aged between 18 and 80 years who had a bilateral mastectomy (or a contralateral mastectomy within 24 months of unilateral mastectomy) with or without a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Main outcome measures

Number and incidence of women without breast cancer who had a bilateral mastectomy; number and proportion who had a bilateral mastectomy as their first breast cancer operation, and the proportion of those undergoing bilateral mastectomy who had immediate breast reconstruction.

Results

Among women without breast cancer, the number who had a bilateral mastectomy increased from 71 in 2002 to 255 in 2011 (annual incidence rate ratio 1.16, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.18). In women with breast cancer, the number rose from 529 to 931, an increase from 2% to 3.1% of first operations (OR for annual increase 1.07, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.08). Across both groups, rates of immediate breast reconstruction roughly doubled and reached 90% among women without breast cancer in 2011.

Conclusions

The number of women who had a bilateral mastectomy nearly doubled over the last decade, and more than tripled among women without breast cancer. This coincided with an increase in the use of immediate breast reconstruction.

Keywords: Oncology, Preventive Medicine, Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery

Article summary.

Article focus

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines in England support the use of bilateral mastectomy among healthy women with a high risk of developing breast cancer.

In the USA, bilateral mastectomy among women with unilateral breast cancer has become more common but evidence of improved survival is weak.

We examined trends in use of bilateral mastectomy in English National Health Service (NHS) hospitals among women with and without breast cancer between 2002 and 2011.

Key messages

In 2002, 71 women without breast cancer had a bilateral mastectomy. By 2011, this had increased to 255 women.

Among women with breast cancer who had surgical treatment, the proportion that had a bilateral mastectomy rose from 2.0% in 2002 to 3.1%.

The proportion of women who had immediate breast reconstruction also increased for both groups of women over this period.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study comes from using a national administrative database of all NHS hospital admissions in which we could identify women having a mastectomy and procedure laterality.

The database does not distinguish unilateral from bilateral breast cancer, so we were could not exclude women who had a therapeutic bilateral mastectomy.

Introduction

There are two distinct groups of women who undergo bilateral mastectomy (BM): those without breast cancer but with familial breast cancer or known genetic mutations (BRCA1 or BRCA2) and those with breast cancer in one or both breasts. Guidelines produced by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) state that risk-reducing BM may be appropriate for high-risk women without breast cancer. High-risk is defined as a lifetime risk of 30% or higher, compared with an average risk of 11% in the UK women.1 This advice is consistent with clinical evidence that removal of both healthy (non-cancerous) breasts can reduce the future incidence of breast cancer in high-risk women.2–5

Some women with unilateral breast cancer have the healthy breast removed to reduce their risk of contralateral breast cancer. Both breasts can be removed simultaneously or the contralateral healthy breast can be removed at a later date. Although the contralateral mastectomy may reduce the risk of developing a future malignant breast tumour and the need for further breast cancer treatments, a 2010 Cochrane Review found insufficient evidence of improved survival.5

Over the last two decades in the USA the use of contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy has increased, from 1–2% to around 5% of women having breast cancer surgery.6–9 Several reasons have been suggested for this increase, including wider availability of genetic testing, avoidance of long-term breast surveillance and increased availability of immediate breast reconstruction. Patients and health professionals may also overestimate the risk of contralateral breast cancer.10 However, trends in the UK and rest of Europe may be different as a result of different medical and cultural attitudes toward extensive ablative surgery and aesthetic surgery.11

Our aim was to investigate trends in bilateral mastectomy for women without and with a breast cancer diagnosis in England between 2002 and 2011. We also examined trends in immediate breast reconstruction to assess the role that this might have played.

Methods

Data definitions and selection of cohort

We used data extracted from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database,12 which covers all admissions to English National Health Service (NHS) hospital trusts. A unique patient identifier allows same patient admissions to be linked. Each HES record captures up to 24 procedures, using the UK Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) classification, V.4.4. Diagnoses are recorded using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revisions (ICD-10). Our extract from HES covered the period from 2002 to 2011, using financial years (1 April to 31 March).

Bilateral mastectomy performed as a single operation was identified by the OPCS codes B27 (mastectomy) and Z94.1 (bilateral). Unilateral mastectomy was identified by the code B27 in addition to Z94.2 (right sided), Z94.3 (left sided) or Z94.4 (unilateral). We excluded women with missing information on laterality. Because high rates of missing information were concentrated in 4 of 162 NHS trusts, we re-ran our analyses after excluding these NHS trusts to check the robustness of the estimated trends. Breast-conserving operations were identified by the OPCS codes B28.1, B28.2, B28.3, B28.8 and B28.9.

Breast reconstruction was identified using OPCS codes B29 (breast reconstruction, excluding B29.5 revision), B38 (reconstruction using buttock flap), B39 (reconstruction using abdominal flap), B30.1 (insertion of prosthesis) and S48.2 (insertion of skin expander).

We identified women with breast cancer using the ICD-10 diagnosis codes C50 (malignant neoplasm) and D05 (carcinoma-in situ). The ICD-10 codes do not distinguish bilateral from unilateral breast cancer so it was not possible to identify how many women had a therapeutic BM for bilateral breast cancer. The number of women diagnosed with synchronous bilateral breast cancer is thought to be extremely small and relatively stable since the 1980 s, based on Swedish Cancer Register data and studies from Australasia and the Netherlands.13–16

We selected women aged 18–80 years who fulfilled one of the following two inclusion criteria: (1) they had a BM between 2002 and 2011 or (2) they had a first breast cancer operation between 2002 and 2011 and had a current or previous diagnosis of breast cancer. A previous diagnosis of breast cancer was determined by checking women's HES records going back to April 2000.

From this cohort, we distinguished between two groups of women who underwent BM. The first group comprised of women who did not have a current or previous diagnosis of breast cancer. All women in this group had BM as a simultaneous procedure.

The second group included women who had a current or previous diagnosis of breast cancer. Women in this group underwent simultaneous BM or had a contralateral mastectomy as a separate procedure within 24 months of the unilateral mastectomy. This approach is referred to in this paper as two procedure BM. Removal of a contralateral breast may be decided at the time of the initial cancer diagnosis but only be performed after completion of adjuvant therapies (chemotherapy or in particular radiotherapy). Alternatively, the decision for contralateral mastectomy may be made after genetic assessment/testing and appropriate counselling, during or after any adjuvant treatments.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the number of women who underwent BM each financial year from 2002 to 2011. Of the women without breast cancer we identified, all were aged between 25 and 69 years. We therefore calculated the incidence of BM per 100 000 women in the English population aged 25–69 as a denominator, using figures published by the Office for National Statistics.17 We then used Poisson regression to estimate an annual trend in the use of BM, including year as a linear term.

Among women with breast cancer, we calculated the BM rate as a proportion out of all the first breast cancer operations undertaken that year. We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate the annual trend in the proportion undergoing BM, including year as a linear term, with and without adjusting for age. We report average trends for the period 2002–2009. This is because the number of two procedure BMs is underestimated for 2010 and 2011 because our extract from the HES database extended only up to 31 March 2012, allowing 24 months of follow-up only for women who had a mastectomy before 1 March 2010.

We calculated the percentage of women who underwent immediate breast reconstruction following BM each year, along with the 95% CIs.

In all cases, we tested for a change in trends using spline terms, but only describe linear trends for simplicity of presentation. Reported p values are based on likelihood ratio tests. All analyses were carried out in Stata V.11.

Results

Bilateral mastectomy in women without breast cancer

Between 2002 and 2011, the number of women without breast cancer who underwent simultaneous BM increased from 71 to 255 (table 1). The population incidence increased from 0.4 to 1.3/100 000 women aged 25–69 years with an estimated annual increase of around 16% (incidence rate ratio 1.16, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.18, p<0.001), although increases were smaller in recent years (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Number of women without breast cancer who had a bilateral mastectomy (BM) in England, 2002–2011

| Number of women who had a BM | Incidence per 100 000 women aged 25–69 | Annual trend |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | p Value | |||

| 2002 | 71 | 0.4 | 1.16 (1.13 to 1.18) | <0.001 |

| 2003 | 72 | 0.4 | ||

| 2004 | 101 | 0.6 | ||

| 2005 | 131 | 0.7 | ||

| 2006 | 147 | 0.8 | ||

| 2007 | 201 | 1.1 | ||

| 2008 | 186 | 1.0 | ||

| 2009 | 232 | 1.2 | ||

| 2010 | 238 | 1.3 | ||

| 2011 | 255 | – | ||

Women without breast cancer comprised an increasing fraction of all women undergoing BM, from 11.8% (71/(71+529)) in 2002 to 19.9% in 2009 (232/(232+931); tables 1 and 2). The average age at surgery was 40 years and did not change over this time period.

Table 2.

Number (%) who had a bilateral mastectomy (BM) out of women with breast cancer having their first operation, 2002–2011

| All women who had first breast cancer operation | No of women who had a BM |

Annual trend (2002–2009) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performed as same operation | Performed as two operations | Total (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| 2002 | 25 844 | 308 | 221 | 529 (2.0) | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.08) | <0.001 |

| 2003 | 27 303 | 332 | 263 | 595 (2.2) | ||

| 2004 | 27 643 | 335 | 269 | 604 (2.2) | ||

| 2005 | 29 179 | 369 | 312 | 681 (2.3) | ||

| 2006 | 28 645 | 407 | 307 | 714 (2.5) | ||

| 2007 | 28 702 | 432 | 336 | 768 (2.7) | ||

| 2008 | 29 629 | 493 | 384 | 877 (3.0) | ||

| 2009 | 29 745 | 546 | 385 | 931 (3.1) | ||

| 2010 | 30 760 | 528 | 263* | – | ||

| 2011 | 31 240 | 617 | 93* | – | ||

*These figures are incomplete since our version of the HES database only covers the period up to 31 March 2012.

Bilateral mastectomy in women with breast cancer

Between 2002 and 2009, the number of women with breast cancer who underwent BM increased from 521 to 931, representing an increase from 2.0% to 3.1% of all women undergoing their first breast cancer operation (table 2). The estimated annual increase was around 7% (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.08, p<0.001), with no strong evidence of a change in trends over the period.

The average age at first breast cancer operation was 58 years, for two procedure BM it was 51 years and for simultaneous BM it fell from 57 to 54 years during the study period.

Around two-fifths of BMs were carried out as two procedures, with the contralateral mastectomy being performed within 24 months.

Rates of immediate breast reconstruction 2002–2011

Among women without breast cancer, the immediate breast reconstruction rate increased substantially from 59.2% (95% CI 46.8% to 70.7%) to 90.6% (95% CI 86.3% to 93.9%; table 3). Reconstruction rates were higher among younger women, particularly those under 40 years (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Number (%) of women who underwent immediate breast reconstruction of those who had a bilateral mastectomy (BM), by presence of a breast cancer diagnosis, 2002–2011

| Women without breast cancer |

Women with breast cancer |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM in same operation |

BM in two operations |

|||||

| No | % (95% CI) | No | % (95% CI) | No | % (95% CI) | |

| 2002 | 42 | 59.2 (46.8 to 70.7) | 56 | 18.2 (14.0 to 23.0) | 60 | 27.1 (21.4 to 33.5) |

| 2003 | 47 | 65.2 (53.1 to 76.1) | 43 | 13.0 (9.5 to 17.0) | 80 | 30.4 (24.9 to 36.3) |

| 2004 | 70 | 69.3 (59.3 to 78.1) | 58 | 17.3 (13.4 to 21.8) | 83 | 30.9 (25.4 to 36.7) |

| 2005 | 87 | 66.4 (57.6 to 74.4) | 80 | 21.7 (17.6 to 26.2) | 105 | 33.7 (28.4 to 39.2) |

| 2006 | 106 | 72.1 (64.1 to 79.2) | 93 | 22.9 (18.9 to 27.2) | 142 | 46.3 (40.6 to 52.0) |

| 2007 | 160 | 79.6 (73.4 to 84.9) | 103 | 23.8 (19.9 to 28.1) | 155 | 46.1 (40.7 to 51.6) |

| 2008 | 151 | 81.2 (74.8 to 86.5) | 135 | 27.4 (23.5 to 31.5) | 173 | 45.1 (40.0 to 57.3) |

| 2009 | 203 | 87.5 (82.5 to 91.5) | 185 | 33.9 (30.0 to 38.0) | 201 | 52.2 (47.1 to 57.3) |

| 2010 | 207 | 87.0 (82.0 to 91.0) | 188 | 35.6 (31.5 to 40.0) | 132* | 50.2 (44.0 to 56.4) |

| 2011 | 231 | 90.6 (86.3 to 93.9) | 252 | 40.8 (36.9 to 44.8) | 50* | 53.8 (43.1 to 64.2) |

*These figures are incomplete since our version of the HES database only covers the period up to 31 March 2012.

Among women with breast cancer who had simultaneous BM, the immediate breast reconstruction rate increased from 18.2% (95% CI 14.0% to 23.0%) to 40.8% (95% CI 36.9% to 44.8%). The immediate reconstruction rate among women who underwent BM in two procedures increased from 27.1% (95% CI 21.4% to 33.5%) to 53.8% (95% CI 43.1% to 64.2%).

Discussion

Summary of results

Over the past decade the total number of women in England who had a bilateral mastectomy nearly doubled, from around 600 to 1000 women/year. Proportionally, the largest increase in BM incidence was seen in women without breast cancer. Their number tripled from 71 to 255 between 2002 and 2009, representing an increase in uptake among women aged 25–69.

Overall, the majority of women who underwent BM had breast cancer. In this group there was an increase in the number who underwent BM (in one or two procedures) between 2002 and 2009, representing a modest increase from around 2% to 3% of women undergoing their first breast cancer operation.

Between 2002 and 2011, rates of immediate breast reconstruction after BM roughly doubled to nearly 50% for women with cancer and over 90% for women who did not have breast cancer.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The comprehensiveness of HES enabled us to identify different hospital admissions for the same woman over a long period of time. Because HES links separate episodes of care for the same patient, we could reliably identify contralateral mastectomies performed within 24 months of a first unilateral mastectomy.

The main limitation of HES is the lack of codes indicating whether a breast cancer diagnosis is unilateral or bilateral. This meant that we were unable to exclude from our analysis women with bilateral breast cancer at initial diagnosis, or diagnosed with an occult or new contralateral breast cancer within 24 months of the index cancer. As a result, among women with breast cancer, those who underwent a therapeutic BM are included in our figures. Of women diagnosed with breast cancer in the Swedish Cancer Register, around 1% of women were first diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer and less than half a per cent were diagnosed with contralateral breast cancer within 24 months of a first diagnosis,13 and these rates have remained stable or decreased since the 1980s.14 Two recent population-based studies from Australasia and the Netherlands reported comparable bilateral breast cancer rates of 2.3% and 2.2%, respectively.15 16 Assuming trends in the UK are comparable, it is unlikely that a change in incidence alone could explain the observed increase in BM rates. Increased detection of bilateral breast cancers through the NHS Breast Screening Programme is also unlikely to explain the increase in BM rates, since we found higher rates and larger increases in rates among women aged under 50 years, who would not have been routinely screened over the study period. Improved MRI detection of occult contralateral breast cancers could have contributed to the increase in the rate of contralateral mastectomy following a unilateral mastectomy.18 However, on checking the use of codes for prophylactic surgery within our database, we were able to confirm that, at a minimum, half of these procedures were intended as risk-reducing operations and more than 60% since 2009.

A further limitation of HES, common to administrative databases, is the potential for inaccuracies and omissions in coding.19 Validation work carried out for breast cancer surgery suggests that procedure codes in HES are accurate, 90–93% agreement with data provided by surgeons.20 We carried out a separate analysis to check the impact of missing procedure codes that indicated whether a mastectomy was bilateral, right-sided or left-sided. The rate of missing laterality codes decreased over the study period from around 5.6% to 1.4% of first mastectomies among women with breast cancer. However, underuse of these codes was concentrated in four NHS trusts, so we re-estimated trends after excluding these trusts from our analysis and were able to confirm that the observed increase in the rate of BM was similar that is, an increase from 2% to 3% among women with breast cancer.

Ideally, to estimate changes in BM use among women without breast cancer, the denominator would be the number of women at a high risk of developing breast cancer. Based on a single study, NICE estimated that up to 2500 women aged 30–49 years in England and Wales could be identified each year as having a genetic risk of breast cancer,21 but actual numbers are not published.

By looking at rates of immediate breast reconstruction, we have underestimated the total number of women with breast cancer who underwent breast reconstruction because many women undergo delayed reconstruction following their mastectomy.22 Delayed reconstruction may be recommended when postmastectomy radiotherapy is anticipated, since this can impair the long-term aesthetic results of breast reconstruction.

Comparison with bilateral mastectomy trends in the USA

The dramatic increase in BM among women without breast cancer in England has not been noted in the USA over the past two decades, although an increase could have occurred earlier in the USA.6 In contrast, several US studies have identified an increase in contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy among women with breast cancer.6–9 Although the definitions and populations studied are not exactly the same as ours, the evidence points toward a larger increase in risk-reducing contralateral mastectomy in the USA than in England.

Various reasons have been suggested for the increase in contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy in the USA. One reason may be increased awareness of hereditary risk and the associated use of genetic testing. Additional drivers may be higher screening recall rates and the need for additional breast assessment arising from annual surveillance mammography and MRI undertaken routinely in the USA.23

Refinements of mastectomy techniques (skin-sparing and nipple-sparing) and increased access to breast reconstruction may also have contributed to the increase of contralateral mastectomy. Higher immediate breast reconstruction rates in the USA (up to 40% in 2008 compared with around 20% in the UK) may also partly account for the relatively greater increase in contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy.11 22

Implications for clinical practice

In women at high risk of developing breast cancer, there has been an increase in BM since the publication of NICE guidance (2004 and 2006).1 In an otherwise healthy woman, BM is a radical approach to risk reduction, but has been estimated to reduce the incidence of breast cancer in BRCA carriers by up to 90%.3 NICE emphasises the importance of patient-led decision-making and provides detailed recommendations regarding the need for a specialist multidisciplinary approach that includes psychological counselling, with clear information provided on the extent of risk reduction and the options for breast reconstruction.

The high rate of immediate breast reconstruction after BM among women without breast cancer suggests that reconstruction is widely available for these patients. This seems appropriate as women who undergo breast reconstruction report higher levels of satisfaction with their postsurgery appearance than women who undergo mastectomy alone.22

In women with a personal history or new diagnosis of unilateral breast cancer the value of contralateral mastectomy for risk reduction is more controversial. For this group of women, decision-making is complicated. It is likely that the risk of dying or the need for further cancer treatment is determined primarily by the biology and stage of the index cancer, rather than by a subsequent cancer in the contralateral breast.5 The risk of subsequent cancers is likely to be reduced by the treatment of the index cancer 24 and any future cancers are likely to be surveillance-detected with a correspondingly better prognosis.25 Consequently, a risk-reducing contralateral mastectomy may not confer any benefit. Some women may still prefer to have a contralateral mastectomy to avoid the stress of long-term regular surveillance and risk of a subsequent cancer and related treatment.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, the number of women having a bilateral mastectomy in England has increased. The increase was proportionately greater in women without breast cancer and within this group, 90% have breast reconstruction at the time of their bilateral mastectomy. However, the majority of women who undergo bilateral mastectomy appear to have had unilateral breast cancer. The evidence to support contralateral risk reducing mastectomy in women with breast cancer is limited.

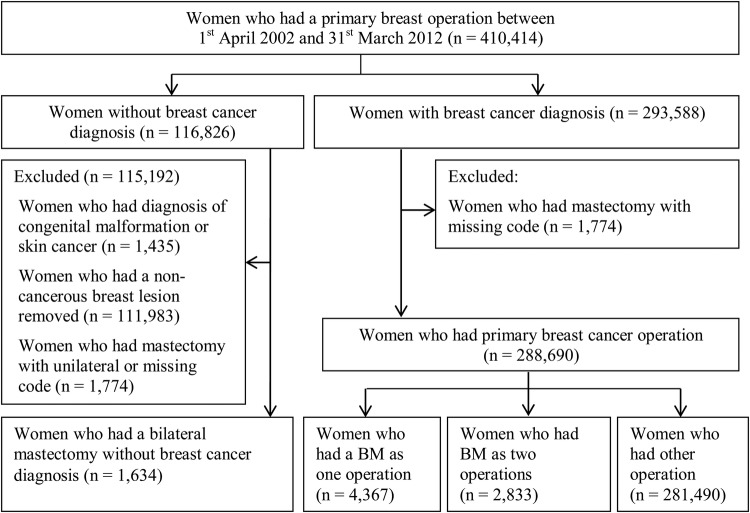

Figure 1.

Sample of women included in the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) for providing the hospital episode statistics used in this study. We thank Lynn Copley for managing and extracting the required data.

Footnotes

Contributors: FM had the original idea for this study. JN carried out the analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to study design, interpretation and writing. DAC is the guarantor. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethical approval: The study is exempt from UK National Research Ethics Committee approval as it involved secondary analysis of an existing dataset of anonymised data for service evaluation. Approvals for the use of hospital episode statistics data were obtained as part of the standard hospital episode statistics approval process.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Familial breast cancer: The classification and care of women at risk of familial breast cancer in primary, secondary and tertiary care. NICE clinical guideline 41. October 2006. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG41/Guidance/pdf/English

- 2.Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1999;340:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Schaid DJ, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:1633–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: The PROSE study group. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1055–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lostumbo L, Carbine NE, Wallace J. Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer (review). Cochrane Collaboration 2010. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002748.pub3/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mclaughlin CC, Lillquist PP, Edge SB. Surveillance of prophylactic mastectomy: trends in use from 1995 through 2005. Cancer 2011;115:5404–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH, et al. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5203–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuttle TM, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, et al. Increasing rates of contralateral mastectomy among patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol 2011;27:1362–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao K, Stewart AK, Winchester DJ, et al. Trends in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral cancer: a report from the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2007. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:2554–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott A, Rueth N, Pappas-Varco S, et al. Perceptions of contralateral breast cancer: an overestimation of risk. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:3129–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albornoz CR, Bach PB, Mehrara BJ, et al. A paradigm shift in US breast reconstruction: increasing implant rates. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;131:24–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Information Centre Hospital Episode Statistics: HES User Guide, 2010. http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=459

- 13.Hartman M, Czene K, Reilly M, et al. Genetic implications of bilateral breast cancer: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:377–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman M, Czene K, Reilly M, et al. Incidence and prognosis of synchronous and metachronous bilateral breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4210–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roder D, de Silva P, Zorbas H, et al. Survival from synchronous bilateral breast cancer: the experience of surgeons participating in the breast audit of the Society of Breast Surgeons of Australia and New Zealand. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2012;13:1413–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Setz-Pels W, Duijm LEM, Groenewoud JH, et al. Patient and tumor characteristics of bilateral breast cancer at screening mammography in the Netherlands, a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;3:955–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office for National Statistics (ONS) Mid-2010 Population Estimates: England; estimated resident population by single year of age and sex. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-231847

- 18.Lehman CD, Gatsonis C, Kuhl CK, et al. MRI evaluation of the contralateral breast in women with recently diagnosed breast cancer. New Engl J Med 2007;356:1295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PbR Data Assurance Framework 2007/08 Findings from the first year of the national clinical coding audit programme. Audit Commission, 2008

- 20.West Midlands Cancer Intelligence Unit Breast Cancer Clinical Outcome Measures Project newsletter: issue 5 August 2009. West Midlands Cancer Intelligence Unit, 2009

- 21.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Familial breast cancer. Partial update of NICE 14. NICE Clinical Guideline 41; 2006. October, Costing Report. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG41/CostingReport/pdf/English [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeevan R, Browne J, van der Meulen J, et al. Fourth annual report of the national mastectomy and breast reconstruction audit 2011. Leeds: The NHS Information Centre, 2011. http://rcseng.ac.uk/surgeons/research/surgical-research/ceu/docs.html [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung A, Huynh M, Lawrence C, et al. Comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and unilateral total mastectomy in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:2600–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzales A, Lacey JV, et al. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1564–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHS Breast Screening Programme Guidelines on organising the surveillance of women at higher risk of developing breast cancer in an NHS Breast Screening Programme. March 2013. http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbsp73.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.