Abstract

Objective

To determine the feasibility of therapy-based, risk-stratified follow-up guidelines for childhood and teenage cancer survivors by evaluating adverse health outcomes in a survivor cohort retrospectively assigned a risk category.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Tertiary level, single centre, paediatric cancer unit in South East Scotland.

Participants

All children and teenagers diagnosed with cancer (<19 years) between 1 January 1971 and 31 July 2004, who were alive more than 5 years from diagnosis formed the study cohort. Each survivor was retrospectively assigned a level of follow-up, based on their predicted risk of developing treatment-related late effects (LEs; levels 1, 2 and 3 for low, medium and high risk, respectively). Adverse health outcomes were determined from review of medical records and postal questionnaires. LEs were graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event, V.3.

Results

607 5-year survivors were identified. Risk stratification identified 86 (14.2%), 271 (44.6%) and 250 (41.2%) as levels 1, 2 and 3 survivors, respectively. The prevalence of LEs for level 1 survivors was 11.6% with only one patient with grade 3 or above toxicity. 35.8% of level 2 survivors had an LE, of whom 9.3%, 58.8%, 18.5%, 10.3% and 3% had grades 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 toxicity, respectively. 65.2% of level 3 survivors had LE, of whom 5.5% (n=9), 34.4% (n=56), 36.2% (n=59), 22.1% (n=36) and 1.8% (n=3) had grades 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 toxicity, respectively.

Conclusions

Therapy-based risk stratification of survivors can predict which patients are at significant risk of developing moderate-to-severe LEs and require high-intensity long-term follow-up. Our findings will need confirmation in a prospective cohort study that has the power to adjust for all potentially confounding variables.

Article summary.

Article focus

Therapy-based risk stratification of survivors can predict which survivors of childhood and teenage cancer are at significant risk of developing moderate-to-severe late effects and require high-intensity long-term follow-up (LTFU).

Key messages

Patients who had received the most complex cancer treatments had the largest number and most severe late effects. Those patients assigned to low-risk category of follow-up had few late effects and those late effects were mild.

Long-term survivors of childhood and teenage cancer can be assigned to primary care, nurse-led or hospital follow-up based on the intensity of treatment they received for the original cancer.

Stratification of patients according to risk of late morbidity will maximise the use of National Health Service resources and provide age appropriate care as locally as possible.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study shows that it is possible to predict which survivors of childhood cancer are at significant risk of developing moderate-to-severe late effects. Life long follow-up for all childhood cancer survivors is not only cost ineffective but also difficult to organise. Until now, there was no evidence available to define the optimum follow-up for long-term survivors.

Risk stratification will enable young adult survivors to benefit from a transition process that takes them into an appropriate follow-up model and can help to identify those survivors who can be discharged from hospital-based follow-up.

Thirty per cent of the cohort had not been seen in the hospital-based late effects service for more than 2 years and health problems may be underestimated in this group.

It would be helpful in future studies to determine the proportion of late effects detected as a direct result of clinic attendance and to determine the proportion of late effects which are treatable.

The study population is small (n=607) and the median age at follow-up is only 19 years, but it does reflect a single centre's clinical practice and as such the findings should stimulate an interesting clinical debate about the utility of LTFU of childhood cancer survivors.

Our findings will need confirmation in a prospective cohort study that has the power to adjust for all confounding variables and in particular for length of follow-up.

Introduction

Dramatic improvements in survival for children with cancer have highlighted the need for evidence-based long-term follow-up (LTFU) for these young people. Approximately 80% of children diagnosed with cancer can now expect to survive more than 5 years, and around 70% will survive 10 years from their diagnosis.1 It is estimated that 1 in 640 young adults is a survivor of childhood cancer.2 As many as two-thirds of long-term survivors are reported to be at increased risk of substantial morbidity and even mortality, due to adverse late effects secondary to cancer or cancer therapy.3–5 Late effects are diverse and include secondary malignancies, organ system damage, infertility, cognitive impairment and disorders of growth and development.6 7 Appropriate LTFU of these patients is essential to detect, treat and prevent morbidity and mortality.8

There is a wide variation of LTFU practices throughout the UK with a propensity for hospital dependency, often in age-inappropriate settings.9 A recent study has highlighted how excess morbidity in survivors translates into increased use of healthcare facilities.10 An awareness of the need for an integrated and systematic approach to follow-up was recognised by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) who developed an evidence-based approach to LTFU.11 This has recently been revised and superceded by SIGN132.12 13 The risks of developing treatment-related late effects depend on the underlying malignancy, the site of the tumour, the type of treatment and the age at time of treatment. A risk-stratified approach to health surveillance was developed which identified three groups of survivors who require an increasing intensity of follow-up.8 In the UK, we published a Practice Statement ‘Therapy Based Long-term Follow-up’ which is designed to inform and guide clinicians responsible for the LTFU of childhood cancer survivors.14 The Practice Statement recommends follow-up assessments and investigations based on the treatment that the individual has received and is informed by the evidence-based recommendations published by SIGN76.

An integrated and systematic approach is now considered a requirement of the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence Improving Outcomes for Children and Young People with Cancer Guidance (2005) and National Delivery Plan for Children and Young People's Specialist Services in Scotland (2008).15 16 In England, the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (NCSI) has developed as a partnership between the Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and supported by National Health Service (NHS) Improvement, to develop models of care to ensure that those living with and beyond cancer have access to safe and effective care and receive the support they need to lead a life as healthy and active as possible. Improved awareness of cancer survivorship as a chronic health problem will facilitate the development of care pathways that will meet the needs of every patient throughout their lifetime.17

Although there is growing guidance on whom, where and how long-term survivors should be followed up, evidence to show that adopting a model of risk-stratified follow-up is safe is lacking. A recent study has shown that assigning patients to one of the three agreed levels of follow-up, as described by Wallace et al was relatively simple for experienced clinic staff.18 The objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of this risk-based follow-up model by retrospectively stratifying an unselected cohort of long-term survivors of childhood cancer from a single centre and objectively evaluating their health status.

Methods

Study population

All patients, aged less than 19 years, who were diagnosed with childhood cancer in a single institution in South East Scotland, between 1971 and 2004, and who were alive at least 5 years from diagnosis, were included in the study. The patients were identified from the Oxford Children's Cancer Registry, established in 1992; patients diagnosed before 1992 were identified from the Scottish Cancer Registry, established in 1958, and hospital records.

Data collection

All health problems directly attributable to cancer, or cancer therapy, were obtained from medical records, electronic hospital record systems, self-reported questionnaires. Medical data were obtained from medical records, electronic hospital records, clinical correspondence from other health professionals and self-completed health status questionnaire and is likely to be an underestimate of the health problems. Cause of death for the deceased patients, as assigned by the General Register Office for Scotland, was obtained from the Scottish Cancer Registry, courtesy of Information Services Division, NHS National Services, Scotland (personal communication).

Therapy-based risk stratification

The SIGN has developed an evidence-based approach to LTFU, incorporating the risk-based levels of follow-up described in 2001.8 Patients are classified into one of the three groups (levels 1, 2 and 3): level 1 patients, treated with surgery alone or low-risk chemotherapy treatment, who could be followed up by postal or telephone contact; level 2 patients, treated with standard risk chemotherapy, such as survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) or lymphoma, who are considered to be at moderate risk of developing late effects, for example, anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, could be followed up by an appropriately trained individual, such as a late effects nurse specialist; level 3 patients, who would require medically supervised follow-up within a multidisciplinary team—that is, those patients that have had a central nervous system (CNS) tumour (treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy), bone marrow transplants, stage 4 disease, any radiotherapy except low-dose cranial radiotherapy and those that have had intensive therapy. Risk-stratified levels of follow-up were independently assigned to all survivors by two researchers. The level of follow-up was retrospectively assigned to each patient, as if they were 5 years from diagnosis and before any medical review of late effects was undertaken.

Grading of late effects

To determine the severity of late effects, each reported late effect was graded independently by two of the authors using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, V.3.0 (CTCAEv3.0, available at http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf), a scoring system developed through the US National Cancer Institute by a multidisciplinary group and adopted in the UK by the Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group.19 The CTCAEv3.0 tool can be used for acute and chronic conditions in patients with cancer and grades conditions as mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe (grade 3), life threatening or disabling (grade 4) or adverse event-related death (grade 5). To investigate and reduce interobserver variability, graded adverse events were compared and inconsistencies were discussed and detailed coding rules were developed (available on request form the authors). Inconsistencies in grading revolved mainly around scoring subjective psychosocial and neuropsychological items of grade 1 or 2, grading of 3 or higher adverse events was straightforward.

Analysis

The statistical package for social sciences Windows V.14.0 was used for the statistical analyses. Data were analysed by descriptive techniques using frequencies, percentages and medians as appropriate.

Results

Study population

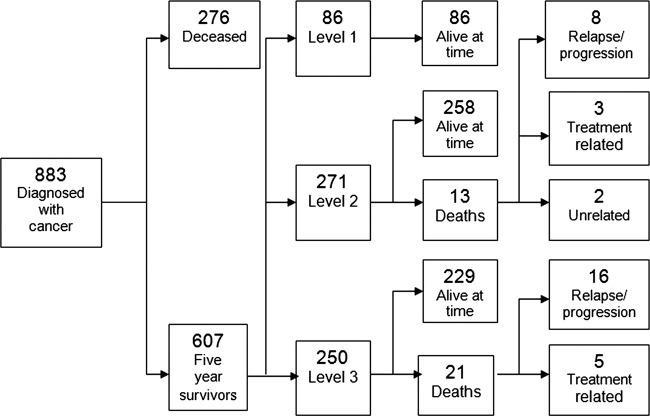

In total, 883 patients were diagnosed with childhood and teenage cancer between 1 January 1971 and 1 July 2004 and 607 of these patients were alive 5 years from diagnosis (5-year overall survival rate 69%). Medical information was collected from a retrospective case-note review, regional electronic hospital systems and self-reported health outcomes from questionnaires. Of the 607 5-year survivors, 34 patients were deceased (5.6%) at the time of the study (figure 1). Of the 573 long-term survivors alive at the time of this study, 122 patients were not known to be under any kind of hospital review (21%). Of the 451 patients under hospital follow-up, 370 (82%) were followed up within the South East Scotland Late Effects Service, either by postal questionnaire follow-up (n=67, 17%) or clinic appointment (n=307, 83%). The remaining 81 (18%) survivors attended other paediatric hospital-based clinics within the same paediatric setting (n=14) or in Tayside (n=26) or Adult Services in South East Scotland (n=31) and in other cities throughout the UK (n=10). Data were gathered from medical records from information based on a clinic visit of more than 2 years previously, without supplementation from postal questionnaires in 178 patients (31%) and is likely to represent an underestimate of late effects.

Figure 1.

Study flow of childhood and teenage patients with cancer. Flow chart showing the study population and the risk stratification of patients into levels 1, 2 and 3 and the proportion of patients alive at the time of the study.

Demographics

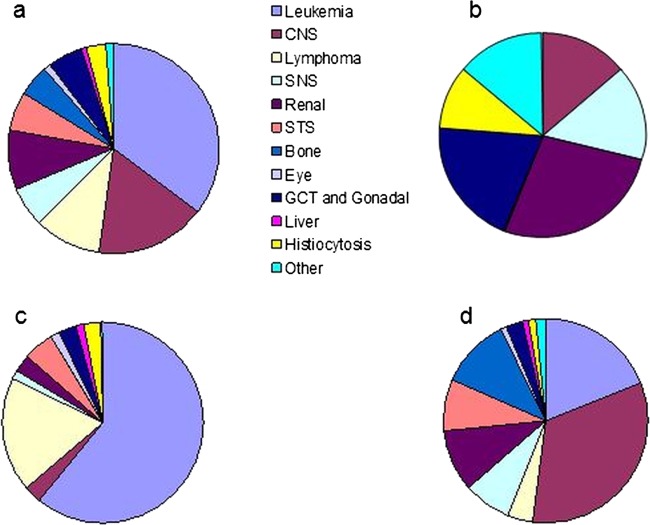

In this population-based study, 607 long-term survivors were identified (males 321 (52.9%)) with median age (range) of 19.2 (5.1–45.1) years and median age (range) at diagnosis 5.1 (0.0–17.5) years. Of the cohort, 34 (5.6%) were deceased, with a median overall survival (range) of 9.9 (5.0–30.9) years. Of the 573 long-term survivors alive at the time of the study, the median age (range) was 19.4 (5.1–45.1) years and disease-free survival (range) 11.3 (0.8–38.3) years (table 1). The primary cancer diagnosis is shown for all patients and within each risk level (figure 2). Risk stratification of all long-term survivors (n=607) identified 86 (14.1%), 271 (44.6%) and 250 (41.2%) at levels 1, 2 and 3, respectively, with detailed breakdown of ages and survival interval for each level of patients alive at the time of the study only (n=573), shown in table 1 and figure 1. Demographic data are similar between the three populations.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of all the 5-year survivors alive at the time of the study (n=573) and for levels 1, 2 and 3 subgroups

| Characteristic | Five-year survivors (n-573) |

Level 1(n=86) |

Level 2 (n=258) |

Level 3 (n=229) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 303 | 52.9 | 37 | 43 | 137 | 53.1 | 129 | 56.3 |

| Female | 270 | 47.1 | 49 | 57 | 121 | 46.9 | 100 | 43.7 |

| Current age (years) | ||||||||

| 5–9 | 44 | 7.7 | 11 | 12.8 | 15 | 5.8 | 18 | 7.8 |

| 10–14 | 110 | 19.2 | 19 | 22.1 | 56 | 21.7 | 35 | 15.3 |

| 15–19 | 148 | 25.8 | 31 | 36.0 | 66 | 25.6 | 51 | 22.3 |

| 20–24 | 129 | 22.5 | 19 | 22.1 | 51 | 19.8 | 59 | 25.8 |

| 25–29 | 69 | 12.0 | 6 | 7.0 | 30 | 11.6 | 33 | 14.4 |

| 30–34 | 40 | 7.0 | – | – | 16 | 6.2 | 24 | 10.5 |

| 35–39 | 21 | 3.7 | – | – | 15 | 5.8 | 6 | 2.6 |

| 40–44 | 11 | 1.9 | – | – | 8 | 3.1 | 3 | 1.3 |

| 45–49 | 1 | 0.2 | – | – | 1 | 0.4 | – | – |

| Median (range) | 19.4 | 5.1–45.1 | 17.5 | 5.1–28.4 | 19.4 | 8.0–45.1 | 20.1 | 5.6–43.7 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||||

| 0–4 | 286 | 49.9 | 54 | 62.8 | 140 | 54.3 | 92 | 40.2 |

| 5–9 | 144 | 25.1 | 16 | 18.6 | 68 | 26.4 | 60 | 26.2 |

| 10–14 | 122 | 21.3 | 15 | 17.4 | 48 | 18.6 | 59 | 25.8 |

| 15–19 | 21 | 3.7 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.7 | 18 | 7.8 |

| Median (range) | 5.0 | 0–20.9 | 2.9 | 0–15.4 | 4.5 | 0–20.9 | 6.5 | 0–17.5 |

| Time from diagnosis (years) | ||||||||

| 5–9 | 197 | 34.4 | 33 | 38.4 | 80 | 31.0 | 84 | 36.7 |

| 10–14 | 166 | 29.0 | 32 | 37.2 | 76 | 29.5 | 58 | 25.3 |

| 15–19 | 100 | 17.5 | 11 | 12.8 | 38 | 14.7 | 51 | 22.3 |

| 20–24 | 58 | 10.1 | 8 | 9.3 | 30 | 11.6 | 20 | 8.7 |

| 25–29 | 30 | 5.2 | 2 | 2.3 | 16 | 6.2 | 12 | 5.2 |

| 30–34 | 12 | 2.1 | – | – | 10 | 3.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| 35–39 | 10 | 1.7 | – | – | 8 | 3.1 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Median (range) | 12.4 | 5.0–39.3 | 11.0 | 5.0–26.9 | 13.0 | 5.0–38.4 | 12.9 | 5.0–39.3 |

| DFS (years) | ||||||||

| 0–4 | 36 | 6.3 | 1 | 1.2 | 20 | 7.7 | 15 | 6.5 |

| 5–9 | 198 | 34.5 | 34 | 39.5 | 82 | 31.8 | 82 | 35.8 |

| 10–14 | 160 | 27.9 | 31 | 36.0 | 67 | 26.0 | 62 | 27.1 |

| 15–19 | 84 | 14.7 | 10 | 11.6 | 34 | 13.2 | 40 | 17.5 |

| 20–24 | 57 | 9.9 | 8 | 9.3 | 31 | 12.0 | 18 | 7.9 |

| 25–29 | 19 | 3.4 | 2 | 2.4 | 8 | 3.1 | 9 | 3.9 |

| 30–34 | 17 | 3.0 | – | – | 15 | 5.8 | 2 | 0.9 |

| 35–39 | 2 | 0.3 | – | – | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Median (range) | 11.3 | 0.5–38.3 | 10.9 | 4.4–26.9 | 11.6 | 1.9–36.4 | 11.6 | 0.5–38.3 |

| Time since last seen in hospital-based late effects clinic (years) | ||||||||

| 0–2 | 328 | 57.2 | 31 | 36.0 | 143 | 55.4 | 154 | 67.2 |

| 3–4 | 75 | 13.1 | 16 | 18.6 | 36 | 13.9 | 23 | 10.1 |

| 5–7 | 78 | 13.6 | 20 | 23.3 | 40 | 15.5 | 18 | 7.9 |

| 8–10 | 28 | 5.0 | 6 | 7.0 | 10 | 3.9 | 12 | 5.2 |

| >10 | 41 | 7.1 | 8 | 9.3 | 19 | 7.4 | 14 | 6.1 |

| Unknown | 23 | 4.0 | 5 | 5.8 | 10 | 3.9 | 8 | 3.5 |

| Median (range) | 2.3 | 0–13.1 | 4.5 | 0–12.7 | 2.2 | 0–12.7 | 1.8 | 0–13.1 |

DFS, disease free survival.

Figure 2.

Diagnoses of 5-year survivors (n-607). (1a) All survivors (n=607), (1b) level 1 (n=86), (1c) level 2 (n=271), (1d) level 3 (n=250). CNS, central nervous system tumours; GCT, germ cell tumours; SNS, sympathetic nervous system tumours; STS, soft tissue sarcomas.

Adverse health outcomes according to level of risk

Among the 34 deaths in the 5-year survivors (n=607), 26 (76.5%) died from progression or relapse of the underlying primary cancer, 2 (5.9%) died from unrelated causes and 6 (17.6%) died from treatment-related sequelae; 5 died from second primary malignancy and 1 from end-stage renal failure. Of the five survivors who went on to die from second primary malignancy, three patients (all level 2) had a meningioma, presumed to be secondary to low-dose cranial irradiation as part of CNS-directed therapy for the treatment of childhood ALL, one (level 3) developed extensive intra-abdominal desmoid tumour having previously been treated for medulloblastoma and with a background of APC gene and Turcot's syndrome and the other patient (level 3) developed acute myeloid leukaemia, presumed to be related to previous topoisomerase II inhibitor therapy for primary bone sarcoma (figure 1).

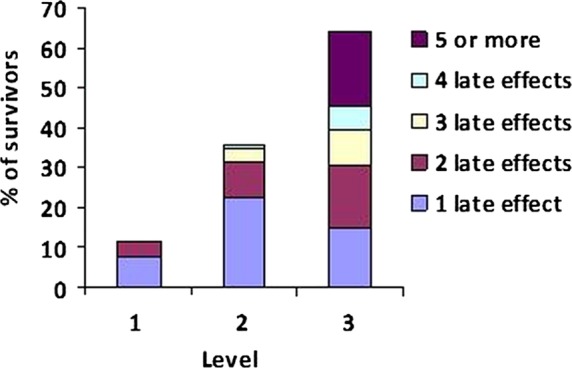

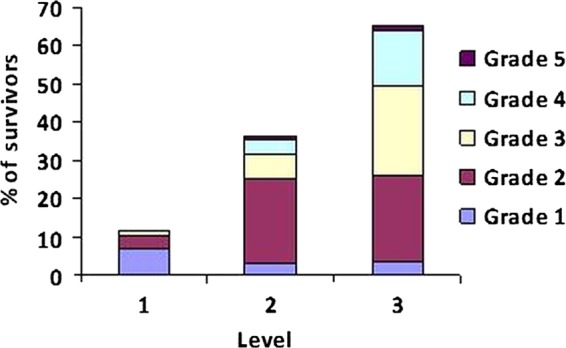

Prevalence and severity of treatment-related late effects were determined for each patient with an assigned level of follow-up (n=607, figures 3 and 4). Among level 1 survivors (n=86), 11.6% (n=10) had late effects, of whom seven (8.1%) had one late effect and three (3.5%) had two late effects: 60% (n=6) of whom were of grade 1 toxicity, 30% (n=3) of whom were of grade 2 toxicity and 10% (n=1) were of grade 3 toxicity. Within the level 2 group (n=271), the prevalence of late effects was 35.8% (n=97), of whom 62 (22.9%) had one late effect, 23 (8.5%) had two late effects, 9 (3.3%) had three late effects and 3 (1.1%) had four late effects, of whom 9.3% (n=9) had a maximum toxicity grade of 1, 58.8% (n=57) grade 2, 18.5% (n=18) grade 3, 10.3% (n=10) grade 4 and 3% (n=3) grade 5. The prevalence of late effects in the level 3 survivors (n=250) was 65.2% (n=163) of whom 37 (14.8%) had one late effect, 39 (15.6%) had two late effects, 22 (8.8%) had three late effects, 16 (6.4%) had four late effects and 46 (18.4%) had five or more late effects, of whom 9 (5.5%), 56 (34.4%), 59 (36.2%), 36 (22.1%) and 3 (1.8%) had grades 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 toxicity, respectively.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of late effects by risk-stratified level of follow-up for all 5-year survivors (n=607).

Figure 4.

Severity of late effects by risk-stratified level (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, V.3.0): grade 1—mild, grade 2—moderate, grade 3—severe, grade 4—life threatening or disabling and grade 5—death for all 5-year survivors (n=607).19

Discussion

We have shown that therapy-based risk stratification of long-term survivors of childhood and teenage cancer can predict which patients are at risk of developing moderate-to-severe side effects and require high-intensity clinic-based LTFU. Retrospective assignment of patients into a risk category identified that almost half (45%) of patients could be considered at moderate risk of developing late effects, while 41% were deemed to be at high risk of developing late effects, with only a small proportion felt to be at low risk of late complications. The prevalence and severity of side effects increased with increasing level of follow-up.

Lifelong follow-up is recommended for survivors of childhood cancer because many of the health problems may be reduced by prevention or early detection.18 However, follow-up should be individually tailored and hospital-based follow-up should not be necessary for all survivors.20 The incidence of chronic conditions continues to increase with time21 and there is therefore no safe time after which these patients can be discharged.22 There is increasing evidence that with increasing time from diagnosis, medical problems associated with ageing, including second cancers, cardiovascular disease, infertility and osteoporosis, may exhibit an accelerated course following certain cancer treatments.23 Mertens et al24 showed that while recurrent disease remains the most important contributor to late mortality in 5-year survivors, there is a significant excess mortality risk associated with treatment-related complications that is present in the 25 years after the initial cancer diagnosis.

It is reported that up to 50% of long-term survivors do not attend Late Effects Clinics and many of these patients are considered to be at high risk of developing treatment-related late complications.25 There are many reasons why survivors choose not to participate in LTFU including the lack of awareness of risks of late morbidity, desire to ‘move on’, lack of appropriate adult services and clinical discharge. In a study by Blaauwbroek et al,26 they assessed late effects in a group of adult survivors of childhood cancer who were not involved in regular LTFU and reported that almost 40% of survivors suffered from moderate-to-severe late effects and 33% had previously unknown late effects. This reiterates the need to educate survivors about their medical history, their treatment and the importance of engaging in regular survivorship programmes.

Low rates of participation in LTFU are universally reported. In 2004, a Delphi panel of 20 expert childhood cancer survivors in the USA identified a number of barriers contributing to this.27 Understanding these barriers will lead to improved medical care for these patients. It was recognised that most childhood cancer survivors are not aware of their adverse health risks and often unaware of the details of their cancer or its treatment. Even where LTFU clinics are attended, much of the education of late effects was directed at parents and often not transferred to the child. The Delphi panel also highlighted the limitations within the healthcare setting including lack of LTFU service, discharge to primary care physician who lacks expertise in this field and often receive no communication about the child's medical history. Improving communication between professionals and patients is essential and will be an integral part of development of survivorship programmes.

The traditional model of LTFU has been in paediatric oncology clinics, generally jointly with paediatric endocrinologists, neurologists and clinical oncologists, long into adulthood which brings with it the advantage of continuity of care, familiarity with treatments, but there are a number of disadvantages to this system. This is not only an age appropriate environment for these patients but also an unsustainable situation for paediatric oncologists, as the population of long-term survivors increase and age. In addition, survivors are protected in this paediatric environment and do not develop the skills necessary to navigate the healthcare system as they develop into adulthood. Ideally, once the long-term survivor reaches adulthood, he/she should be transitioned into the appropriate adult late effects services. At present, such a service does not exist and it is difficult to identify which clinicians should take on this role, especially with increasing subspecialisation in adult medicine. In a busy and overstretched tertiary oncology healthcare service, medical and clinical adult oncology consultants are unlikely to be in a position to take on this responsibility, and may well feel inadequately trained in caring for childhood cancer survivors. In current practice, the only adult services supporting the LTFU of those patients requiring specialist hospital follow-up are the adult endocrine and neurology clinics.

It has been highlighted that improved communication of cancer information to patients/families and between healthcare providers may contribute to greater engagement in follow-up programmes, raises awareness of potential late effects among survivors and enable clinicians to diagnose and, where possible, treat late effects earlier.12 13 Based on national guidelines, we have developed a template for the End of Treatment Summary and Individualised Care Plan, or ‘Health Passport’, which has been introduced nationally, and welcomed by health professionals and survivors.

Models of care for LTFU of survivors of childhood cancer must be flexible enough to accommodate the needs of the young survivor as they transition throughout their life cycle and also to accommodate the individual heterogeneity of cancer survivors, reflecting the wide range of treatment exposure and adverse long-term sequelae. Development of a service that can deliver individualised, comprehensive, therapy-based patient-centred care is essential.

The UK NCSI is currently exploring models of aftercare services for children and young people who have been treated for cancer. National pathways that identify how follow-up can be delivered in line with current pressures and aspirations are being developed. Clinical risk stratification will play an integral role in tailoring individualised care to meet the clinical, psychological and practical needs of each survivor. A recent study from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) has reviewed how data derived from the CCSS have characterised specific groups that are deemed to be at highest risk of morbidity and subsequent cancers.28 Our study has shown that those patients at highest risk of late morbidity can be identified and appropriately stratified into a high risk (level 3) follow-up programme.

Our study has a number of important but acknowledged limitations. There are only 605 5-year survivors and the median age at follow-up was only 19 years, so the study population is small but it does reflect a single centre's clinical practice and as such the findings should stimulate an interesting clinical debate about the utility of LTFU of childhood cancer survivors. We have not undertaken any formal statistical analysis but believe that our data are best presented as visual figures (3 and 4) showing clearly that both the prevalence and severity of late effects are related to the assigned level of follow-up in our unselected cohort. We have not been able to statistically adjust our analysis to take into account of the current age of survivors for each assigned level of follow-up. The percentage of 5-year survivors with a current age beyond 25 years is 7%, 27% and 29% for levels 1, 2 and 3, respectively. It is possible that as the level 1 group ages, more late effects will appear and although this appears unlikely, as this group has received the least intensive treatment, it should be the subject of the ongoing and further study. The median follow-up time for levels 1, 2 and 3 survivors is 11, 13 and 12.9 years, respectively (see table 1). We believe that the ascertainment of adverse health outcomes is likely to be complete or very nearly complete in our study population, although we must acknowledge that we were not able to access primary care records for our 5-year survivors which could result in an under-reporting of adverse events. It is, however, highly unlikely that missed adverse health outcomes were more likely in level 1 patients as opposed to level 2 or 3 patients.

Stratification of patients according to risk of late morbidity will maximise the use of health service resources and provide age appropriate care as locally as possible. With increasing time from the completion of treatment, it is hoped that the majority of adult survivors will be independent and take responsibility for their own health, with healthcare support provided by their primary care physician. As a result, the primary care team is likely to play an increasing role in the LTFU of survivors of childhood cancer. Primary care services may be already stretched, but general practitioners (GPs) are used to meeting targets and ensuring guidelines are implemented. Good communication between the hospital services and primary care will be essential. Early involvement of GPs in the late effects services will establish collaborations between the two teams and enable primary care physicians to become familiar with the surveillance programme. The feasibility of a shared-care model between cancer paediatric oncology cancer centres and primary-care doctors to deliver survivor-focused risk-based healthcare was tested successfully by a Dutch group. The study showed that patients would see their family doctor for LTFU: the family doctors were interested in sharing survivors’ care and family doctors would return the necessary medical information needed for the continued follow-up.29 Appropriate education of the family doctors, which has resource implications, was a key finding of this study. Recently, this group has shown that a web-based survivor care plan can facilitate the long-term care of survivors by family doctors.30

In order to improve our understanding of treatment-related side effects and help develop treatment protocols to minimise toxicity, lifelong monitoring of health and well-being of all long-term survivors will be necessary. Our understanding of the late effects of the treatment of Hodgkin's lymphoma has led to studies which are ongoing and are designed to reduce the risk of second malignancy by avoiding radiotherapy in selected cases and replace gonadotoxic chemotherapy with drugs that are efficacious in Hodgkin's lymphoma but less likely to compromise reproductive function.31 Balancing safety and efficacy in the treatment of Hodgkin's lymphoma remains an important goal in the treatment of this curable malignancy.32

We have shown that it is possible to predict which survivors of childhood cancer are at a significant risk of developing moderate-to-severe late effects and require moderate or high-intensity long-term follow. Importantly, we have also shown in our small population-based cohort of 5-year survivors that there is a group of survivors who can be reliably identified who may be discharged from clinic-based follow-up and followed up by annual questionnaire or telephone contact. Our findings need confirmation in a prospective cohort study that has the power to adjust for all confounding variables and in particular for the length of follow-up. Structured, risk-adapted follow-up of childhood cancer survivors following evidence-based guidelines would reduce cost ineffective or excessive evaluations and focus individual healthcare delivery. Education of survivors and healthcare providers will hopefully reduce the burden of chronic health problems and improve the quality of life for the growing population of children and young people who have been treated for cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr David Brewster, Director, Scottish Cancer Registry and Douglas Clark, Information Analyst, Information Services Division, NHS National Services Scotland, for providing valuable information on the deceased patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: EAB initiated the project, designed data collection tools, monitored data collection for the study, analysed the data and drafted and revised the paper. DK designed data collection tools, monitored data collection for the study, analysed the data and revised the draft paper. BS designed data collection tools, monitored data collection for the study, analysed the data and revised the draft paper. M-SP analysed the data and drafted and revised the paper. WWH designed data collection tools, monitored data collection for the study, analysed the data and drafted and revised the paper. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was requested from the Lothian Research Ethics Committee (LREC). On review by the LREC, the committee decided that ethical approval was not required as long-term follow-up of childhood cancer survivors was deemed to be an acceptable and routine part of clinical practice and there were no experimental interventions.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Dataset available from the corresponding author at angela.edgar@luht.scot.nhs.uk. Consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK Childhood cancer—UK statistics. Cancer Research UK, 2004. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/childhoodcancer/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell J, Wallace WH, Bhatti LA, et al. Cancer in Scotland: trends in incidence, mortality and survival 1975–1999. Edinburgh: Information & Statistics Division, 2004. http://www.isdscotland.org/cancer_information [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lackner H, Benesch M, Schagerl S, et al. Prospective evaluation of late effects after childhood cancer therapy with a follow-up over 9 years. Eur J Pediatr 2000;159:750–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oeffinger KC, Eshelman DA, Tomlinson GE, et al. Grading of late effects in young adult survivors of childhood cancer followed in an ambulatory adult setting. Cancer 2000;88:1687–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens MC, Mahler H, Parkes S. The health status of adult survivors of cancer in childhood. Eur J Cancer 1998;34:694–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DL, Meadows AT. Late effects of childhood cancer therapy. Pediatr Clin North Am 2002;49:1083–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia S, Landier W. Evaluating survivors of pediatric cancer. Cancer J 2005;11:340–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace WH, Blacklay A, Eiser C, et al. Developing strategies for long-term follow-up of survivors of childhood cancer. BMJ 2001;323:271–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor A, Hawkins M, Griffiths A, et al. Long-term follow-up of survivors of childhood cancer in the UK. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004;42:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebholz CE, Reulen RC, Toogood AA, et al. Health care use of long-term survivors of childhood cancer: the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4181–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SIGN 76: Long-term follow-up care of survivors of childhood cancer. http://www.SIGN.ac.uk

- 12.SIGN 132: Long-term follow-up care of survivors of childhood cancer. http://www.SIGN.ac.uk

- 13.Wallace WH, Thompson L, Anderson RA. Guideline development group. BMJ 2013;346:f1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Late Effects Group In: Skinner R, Wallace WHB, Levitt GA, eds. Therapy based long-term follow-up. Practice statement 2nd edn UK Children's Cancer Study Group, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 15.2005. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence Improving Outcomes Guidance for Children and Young People with Cancer. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. http://www.nice.org.uk.

- 16.2008. National Delivery Plan for Children and Young People's Specialist Services in Scotland: Draft for Consultation. http://www.scotland.gov.

- 17.Models of care to achieve better outcomes for children and young people living with and beyond cancer. National Cancer Survivorship Initiative. Children and Young People Workstream. http://www.ncsi.org.uk/what-we-are-doing/children-young-people/

- 18.Eiser C, Absolom K, Greenfield D, et al. Follow-up after childhood cancer: evaluation of a three-level model. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:3186–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute, Common Terminology for Adverse Events. http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf

- 20.Jenney M, Levitt G. Follow-up of children who survive cancer. BMJ 2008;336:732–3 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diller L, Chow EJ, Gurney JG, et al. Chronic disease in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort: a review of published findings. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2339–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklaar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1572–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oeffinger KC, Wallace WH. Barriers to follow-up care for survivors in the United States and United Kingdom. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2006;46:135–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, et al. Late mortality experience in five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3161–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgar AB, Borthwick S, Duffin K, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer lost to follow-up can be re-engaged into active long-term follow-up by a postal health questionnaire intervention. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1066–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blaauwbroek R, Stant AD, Groenier KH, et al. Late effects in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the need for life-long follow-up. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1898–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zebrack BJ, Eshelman DA, Hudson AC, et al. Health care for childhood cancer survivors. Insights and perspectives from a Delphi panel of young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer 2004;100:843–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson MM, Mulrooney DA, Bowers DC, et al. High-risk populations identified in Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Investigations: implications for risk-based surveillance. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2405–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blaauwbroek R, Tuinier W, Meyboom B, et al. Shared care by paediatric oncologists and family doctors for long-term follow-up of adult childhood cancer survivors: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:232–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blaauwbroek R, Barf HA, Groenier KH, et al. Family doctor-driven follow-up for adult childhood cancer survivors supported by a web-based survivor care plan. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6:163–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson AB, Wallace WH. Treatment of paediatric Hodgkins disease: a balance of risks. Eur J Cancer 2002;38:468–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metzger ML, Hudson MM. Balancing efficacy and safety in the treatment of adolescents with Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6071–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.