Abstract

Objectives

To quantify mortality associated with sepsis in the whole population of England.

Design

Descriptive statistics of multiple cause of death data.

Setting

England between 2001 and 2010.

Participants

All people whose death was registered in England between 2001 and 2010 and whose certificate contained a sepsis-associated International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code.

Data sources

Multiple cause of death data extracted from Office for National Statistics mortality database.

Statistical methods

Age-specific and sex-specific death rates and direct age-standardised death rates.

Results

In 2010, 5.1% of deaths in England were definitely associated with sepsis. Adding those that may be associated with sepsis increases this figure to 7.7% of all deaths. Only 8.6% of deaths definitely associated with sepsis in 2010 had a sepsis-related condition as the underlying cause of death. 99% of deaths definitely associated with sepsis have one of the three ICD-10 codes—A40, A41 and P36—in at least one position on the death certificate. 7% of deaths definitely associated with sepsis in 2001–2010 did not occur in hospital.

Conclusions

Sepsis is a major public health problem in England. In attempting to tackle the problem of sepsis, it is not sufficient to rely on hospital-based statistics, or methods of intervention, alone. A robust estimate of the burden of sepsis-associated mortality in England can be made by identifying deaths with one of the three ICD-10 codes in multiple cause of death data. These three codes could be used for future monitoring of the burden of sepsis-associated mortality.

Keywords: STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH

Article summary.

Article focus

A large proportion of patients admitted to critical care units with sepsis die; if sepsis is identified and treated earlier, mortality can be reduced producing cost-effective benefits in terms of life years/quality-adjusted life years gained.

Assessing sepsis-associated mortality is not straightforward as there are no codes for sepsis in International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) and sepsis-related conditions are often not selected as the underlying cause of death.

Multiple cause of death (MCOD) data are now available for deaths in the UK and provide a way of determining those that are associated with sepsis.

Key messages

In 2001–2010, 1 in 20 deaths in England was associated with sepsis based on information recorded on death certificates,

Ninety-nine per cent of deaths definitely associated with sepsis include one of three ICD-10 codes, A40, A41 and P36, somewhere on the list of causes of death.

These deaths occur across a wide range of specialty areas and 15 000 (7%) deaths definitely associated with sepsis in 2001–2010 did not occur in hospital; this should prompt a much wider population-based approach to future quality improvement.

Strengths and limitations of this study

MCOD data are collected for all deaths, allowing us to count all those whose deaths are associated with sepsis, not just those who die in hospital, or those for whom septicaemia is the underlying cause.

Our population estimates are based on the 2001 UK census, which will shortly be updated by the 2011 Census.

The study relies on the accuracy of coding. There is no specific code for sepsis within ICD-10, which may lead to misclassification of causes. We may have underestimated the true impact of sepsis.

Introduction

Sepsis is defined as systemic inflammatory response syndrome caused by infection.1 2 Severe sepsis is sepsis with organ system dysfunction, while septic shock is defined as sepsis with hypotension refractory to fluid resuscitation, leading to inadequate tissue perfusion. These entities lie on a spectrum of diseases culminating with death caused by multiple organ dysfunction.

Twenty-seven per cent of intensive care admissions in England and Wales are for severe sepsis and almost half of these patients die in hospital.3 In 1995–1996, in an adult general intensive care unit (ICU) in a UK university hospital, the median cost of treating a patient with sepsis was six times the cost of treating a patient without sepsis. The mortality rate was also significantly higher for the sepsis patients, despite the increased spending, at 53% compared with 29% for non-sepsis patients.4 More recent studies have found that using integrated sepsis treatment protocols, including those developed by the International Surviving Sepsis Campaign, can be effective at reducing mortality rates.5–7 Such protocols may increase costs through lengthier ICU stays, but appear cost-effective in terms of life years and quality-adjusted life years gained. Estimates of the incidence of sepsis, and associated mortality, are hard to obtain. Recent estimates suggest that the incidence of severe sepsis in the general population is 38/100 000 in Finland8 and 25/100 000 in Spain,9 while older studies have found rates as high as 240–300/100 000 population in the USA.10 11 However, these estimates are based on administrative inpatient data. It is likely that these underestimate the incidence of sepsis as they only count those admitted to hospital. Using multiple cause of death (MCOD) data, it has been estimated that 6% of all deaths in the USA are associated with sepsis.12

In 1993, the redevelopment of the Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality database allowed all the diseases and conditions mentioned on the death certificate to be coded and stored. Up to 15 mentioned causes of death can be coded in addition to the underlying and secondary causes of death.13 MCOD data have been used in England to examine the contribution to mortality of many different diseases and conditions.14–19 Analysis of mortality by the cause of death usually uses the underlying cause of death, which is the ‘disease or injury which initiated the train of morbid events leading directly to death or the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury.’20 For many patients, sepsis may be part of that causal sequence, but it would not be listed as the underlying cause of death. For example, in cases where sepsis is hospital acquired, the original reason for hospitalisation would generally be the underlying cause of death. Consequently, examining mortality from sepsis using the underlying cause of death would not identify those deaths as being sepsis associated.

In this paper, MCOD data have been used to estimate the number of deaths in England associated with sepsis.

Methods

Mortality data were obtained from the ONS mortality database, for the period from 2001 to 2010. As sepsis deaths cannot be directly identified in International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), a list of codes related to sepsis was selected. Using the underlying question—‘If this condition appears on the death certificate, what is the chance this person would have had sepsis?’—a list of conditions was derived. These were then divided into two categories: those definitely meaning sepsis and those which may mean sepsis were involved. The ICD-10 codes associated with these conditions were identified using the ICD-10 index21 and online searching tool developed by WHO and the German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information.22 The first three authors then reviewed the list of codes, by asking the question ‘If this code was recorded on a death certificate, what is the probability that the deceased had severe sepsis?’ If the probability was considered to be more than 50%, then the code was included in a candidate list. This candidate list of codes was crosschecked with the Melamed and Sorvillo12 paper and the ICD ‘List of conditions unlikely to cause death’23 to ensure that no unlikely codes were included and that no likely codes had been overlooked. The ICD-10 codes that are definitely or maybe associated with sepsis are listed in the online supplementary appendix.

Deaths were extracted from the mortality database if they had a mention of any of the identified codes anywhere on the death certificate. Age-specific and sex-specific rates were calculated using mid-year population estimates for England, published in June 2010, as denominators for the relevant year and, where appropriate, death rates were directly age standardised using the European Standard Population.

To look at patterns of sepsis-associated mortality, we also examined the underlying cause of death for these deaths, other comorbidities mentioned on the certificate and the total number of contributing causes mentioned on the death certificate. We compared these with the overall patterns for all deaths in England. We also examined sepsis-associated mortality by the place of death: home, hospital, care home, etc. We restricted these analyses to those deaths definitely considered to be sepsis associated. Deaths under 28 days have a separate death certificate and only mentioned causes are coded for these deaths—an underlying cause of death cannot be selected from them.24 These deaths were included in the majority of analyses in this study and where they have been excluded this has been noted in the results.

Results

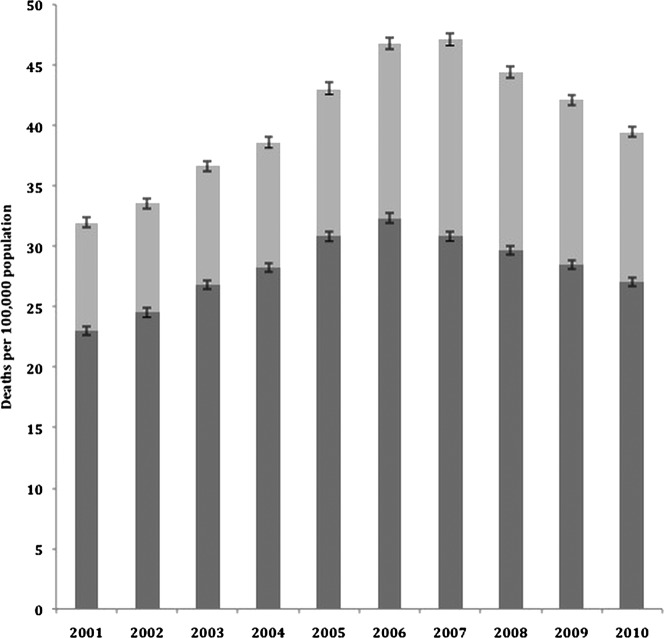

Between 2001 and 2010, there were 226 547 deaths that were definitely directly associated with sepsis in England, 4.7% of all deaths. Adding those that may be related to sepsis increased this to 332 757, 6.9% of all deaths. In 2010 alone, 5.1% of deaths were definitely associated with sepsis, and adding in those deaths that may be related increased that percentage to 7.7%. Figure 1 shows mortality rates for deaths that are definitely and maybe linked to sepsis for each year. For both sexes combined, the rate rose to a peak in 2007 and then declined. Excluding the ‘maybe’ group brings the peak in mortality forward to 2006. The number of deaths definitely associated with sepsis was also the highest in 2006. The number rose from 16 800 in 2001 to a peak of 26 150 in 2006, before decreasing every year to 23 700 in 2010. The remaining analyses in this paper present results only for those deaths definitely associated with sepsis.

Figure 1.

Direct age-standardised rates of death definitely, dark grey, and maybe, light grey, associated with sepsis, England 2001–2010, with 95% CI for the rate.

In 2010, the percentage of deaths associated with sepsis was higher for females (5.5%) than males (4.8%). However, when direct age-standardised rates were calculated (which take into account the differences in the age structures of the population between the sexes), the rate in 2010 was higher for males (29.8 deaths/100 000 population) than females (24.8/100 000). Between 2001 and 2010, the annual death rate for males was 20–28%, higher than the rate for females.

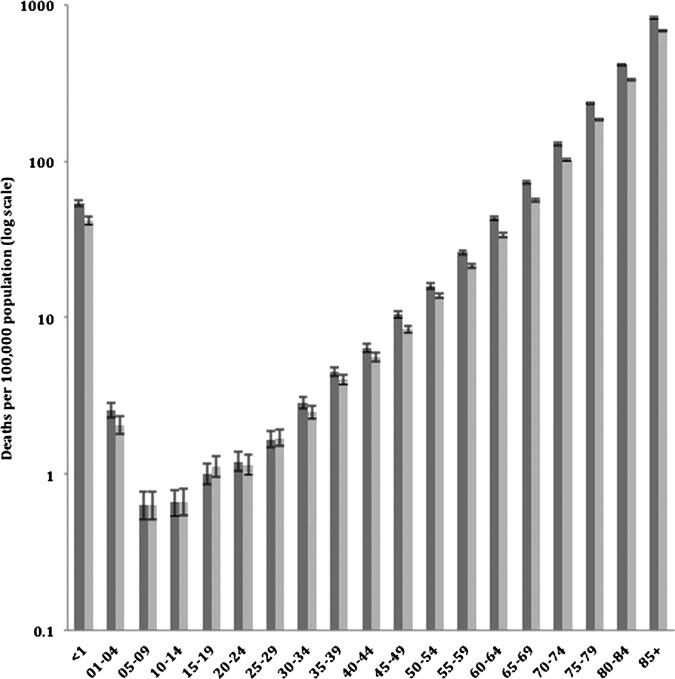

Age-specific mortality rates were higher in the very youngest and elderly, with the rate in the under 1s being similar to the rate among those in their 60s (figure 2). At younger ages, the rate declined rapidly after age 1. In 2001–2010, the age-specific mortality rate for deaths associated with sepsis in ages 5–14 was less than 1/100 000 population for both males and females. Rates then rose with age, with particularly marked increases in the oldest age groups. For both males and females, the rate in the 85+ age group was double the rate for those aged 80–84. The age-specific rate for males was significantly higher than females for deaths under age 1 and for every age group from age 40 onwards. For deaths at age 85 and above, the age-specific rate for men was 822 deaths/100 000 population, compared with 683/100 000 for women.

Figure 2.

Age-specific death rates for males, dark grey, and females, light grey, of deaths definitely associated with sepsis, England, 2001–2010, with 95% CI for the rate.

Table 1 shows the underlying cause for deaths that are definitely sepsis associated, by chapter of the ICD, and the percentage of each ICD chapter, that is, sepsis associated. This does not attempt to identify the cause of sepsis for these deaths, but merely identifies the disease or injury that initiated the train of morbid events leading directly to death. The underlying causes of deaths with a mention of sepsis are spread across a wide spectrum of ICD chapters. The ICD chapter that accounts for the biggest percentage of sepsis-associated deaths is genitourinary diseases (17.8%). The leading causes of death also account for high percentages, such as respiratory diseases (15.4%), digestive diseases (14%), cancer (13.4%) and circulatory diseases (11.5%), while 11.7% of deaths have an underlying cause in the infectious diseases chapter. Almost half of the deaths with an underlying cause of infectious disease are associated with sepsis (49.1%). There are wide differences in the percentages in other chapters. Only 1.5% of circulatory disease deaths are associated with sepsis, but for deaths with an underlying cause of skin disease, three-quarters are associated with sepsis (75.7%). Twenty per cent of deaths from diseases originating in the perinatal period also had a sepsis-associated cause of death on the death certificate. However, it must be borne in mind that deaths under 28 days were not included in the analysis of deaths by the underlying cause, as a different death certificate is used to register these deaths in England.24

Table 1.

Deaths that are definitely associated with sepsis, by underlying cause of death and comparison with all deaths, occurring in England 2001–2010 excluding neonatal deaths

| ICD-10 codes | ICD-10 chapter | Sepsis deaths | All deaths | Percentage of sepsis-associated deaths in chapter | Percentage of all deaths in chapter that are sepsis associated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A00-B99 | Infectious diseases | 26296 | 53543 | 11.7 | 49.1 |

| C00-D48 | Neoplasms | 30210 | 1307155 | 13.4 | 2.3 |

| D50-D89 | Diseases of the blood | 1696 | 9610 | 0.8 | 17.6 |

| E00-E90 | Endocrine diseases | 6995 | 69483 | 3.1 | 10.1 |

| F00-F99 | Mental and behavioural disorders | 1899 | 150122 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| G00-G99 | Nervous system diseases | 3199 | 149773 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| H00-H59 | Eye diseases | 40 | 112 | 0.0 | 35.7 |

| H60-H95 | Ear diseases | 53 | 206 | 0.0 | 25.7 |

| I00-I99 | Circulatory diseases | 25803 | 1708766 | 11.5 | 1.5 |

| J00-J99 | Respiratory diseases | 34581 | 654960 | 15.4 | 5.3 |

| K00-K93 | Digestive diseases | 31550 | 234960 | 14.0 | 13.4 |

| L00-L99 | Skin diseases | 12251 | 16190 | 5.5 | 75.7 |

| M00-M99 | Musculoskeletal diseases | 5215 | 41617 | 2.3 | 12.5 |

| N00-N99 | Genitourinary diseases | 40090 | 96988 | 17.8 | 41.3 |

| O00-O99 | Pregnancy | 41 | 429 | 0.0 | 9.6 |

| P00-P96 | Perinatal period | 372 | 1958 | 0.2 | 19.0 |

| Q00-Q99 | Congenital abnormalities | 568 | 11545 | 0.3 | 4.9 |

| R00-R99 | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings | 17 | 109542 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| V01-Y98, U50.9 | External causes | 3849 | 162139 | 1.7 | 2.4 |

| Total | 224725 | 4800260 | 100.0 | 4.7 |

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision.

We also examined the percentage of sepsis-associated deaths where sepsis was also the underlying cause of death. For deaths definitely considered to be sepsis associated, this was 8.6% in 2010. Of the cases definitely associated with sepsis, 99% contained one of three ICD-10 codes in at least one position on the death certificate: A40 (streptococcal septicaemia), A41 (other septicaemia) and P36 (bacterial sepsis of newborn).

Table 2 shows the total number of causes mentioned on the death certificate for all deaths and for sepsis-associated deaths. Sepsis-associated deaths tend to have more conditions mentioned than all other deaths. For all deaths, two is the most common number of causes mentioned; whereas for sepsis-associated deaths, the most common number is three. Very few sepsis-associated deaths have only one cause of death on the death certificate. This is because ‘sepsis’ alone is not a sufficient feature to allow death to be registered without reference to a coroner: the certificate must mention the cause of the sepsis for this to be acceptable under law. However, it also seems that overall sepsis-associated deaths have proportionally more conditions mentioned, as might be expected given the severity of illness among these individuals. For sepsis-associated deaths, 23.2% have five or more conditions mentioned, compared with 7.2% of all deaths. Neonatal deaths were excluded from this part of the analysis because the conditions mentioned on their death certificates include conditions in the mother and in the baby, so they are not directly comparable to those deaths where the deceased were aged 28 days or older.

Table 2.

Percentage of deaths with given number of diseases or conditions mentioned on the death certificate in deaths definitely associated with sepsis, excluding neonatal deaths, compared with all deaths in England 2001–2010

| Number of causes mentioned | All deaths (%) | Sepsis- associated deaths (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25.1 | 1.1 |

| 2 | 35.1 | 18.8 |

| 3 | 21.9 | 33.0 |

| 4 | 10.6 | 23.9 |

| 5 | 4.4 | 12.8 |

| 6 | 1.7 | 6.0 |

| 7 or more | 1.1 | 4.4 |

Many of the chronic conditions known to be associated with sepsis appear on the death certificates of sepsis-associated deaths: 16.8% of certificates mentioned cancer and 9.4% diabetes (table 3).

Table 3.

Comorbidities mentioned on the death certificates of deaths definitely associated with sepsis, excluding neonatal deaths, in England 2001–2010

| Number of deaths | Percentage of all sepsis-associated deaths | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 37727 | 16.8 |

| Diabetes | 21086 | 9.4 |

| Congestive heart failure | 9957 | 4.4 |

| Chronic renal failure | 12611 | 5.6 |

| Chronic lower respiratory Diseases | 13666 | 6.1 |

| Hypertension | 9375 | 4.2 |

| Chronic liver disease | 6033 | 2.7 |

| HIV | 298 | 0.1 |

| Chronic alcohol abuse | 3719 | 1.7 |

Table 4 shows that 93.4% of all sepsis-associated deaths took place in hospital, compared with 55.6% of all deaths. Nearly 7% of sepsis-associated deaths, therefore, did not take place in the hospital. Less than 2% of sepsis-associated deaths occurred in the deceased's own home, compared with nearly 20% of all deaths. Almost 8% of deaths in hospital were associated with sepsis, compared with less than half a percentage of deaths that took place in the deceased's own home, hospices or elsewhere.

Table 4.

Deaths definitely associated with sepsis, excluding neonatal deaths, compared with all deaths by place of death in England 2001–2010

| Place of death | Sepsis-associated deaths (number (%)) | All deaths (number (%)) | Sepsis-associated deaths (% of all deaths in location) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care home | 10 165 (4.5) | 865 755 (18.0) | 1.2 |

| Elsewhere | 315 (0.1) | 96 632 (2.0) | 0.3 |

| Home | 3495 (1.5) | 915 919 (19.1) | 0.4 |

| Hospice | 609 (0.3) | 232 899 (4.9) | 0.3 |

| Hospital | 211 695 (93.4) | 2 669 925 (55.6) | 7.9 |

| Other communal establishment | 268 (0.1) | 19 131 (0.4) | 1.4 |

| Total | 226 547 (100) | 4 800 261 (100) | 4.7 |

Discussion

Using the information recorded on death certificates for the whole population, we have estimated that at least 1 in 20 of all deaths in England is associated with sepsis. The sepsis-associated death rate has been increasing over the last decade, reaching a peak in 2006. The rate has decreased in more recent years, but not yet to the level in the earlier part of the decade. This was an observational study; but now that this trend in sepsis-related deaths has been identified, it would be a worthwhile research exercise to investigate further why rates have changed over time. We have shown that 6.6% of patients with definite severe sepsis die outside of a hospital, indicating that in 2001–2010 up to 15 000 deaths associated with sepsis may have been missed if we had only counted deaths in hospital. Sepsis-associated deaths appear to have larger numbers of conditions on their death certificates than do all deaths.

Our study does have some limitations. In using MCOD data, it relies on the accuracy of the recording of causes of death on the death certificate. As a study of sepsis-associated deaths in the USA has noted, codes for septicaemia have to be used as a proxy for sepsis in ICD-10. There is a risk that this may lead to the misclassification of deaths, and possibly an underestimation of the burden of sepsis-related mortality.12 We should also note that our mortality rates were calculated using mid-year population estimates which are based on the 2001 Census. In December 2012, ONS planned to release revised mid-year estimates for England, which will take into account the results of the 2011 Census.

Our estimate of deaths associated with sepsis is similar to that found in the USA using a similar method.12 Many current estimates of mortality due to sepsis look at patients admitted to hospital and who subsequently die, giving an indication of case death. It is estimated that the mortality of patients admitted to critical care units and diagnosed with severe sepsis is 47%.3 Our study is population based, and therefore gives an indication of the burden of sepsis across the whole population. Most analyses of cause of death data only look at the underlying cause, which identifies the disease or injury that initiated the events leading to death. We have shown, however, that less than 10% of deaths associated with sepsis have it as the underlying cause. To fully account for sepsis-related mortality, it is therefore necessary to examine all the recorded causes of death, as we have carried out. Although this analysis is more complex than just examining the underlying cause of death, we have shown that just three ICD-10 codes—A40, A41 and P36—identify 99% of deaths definitely associated with sepsis. These three codes alone could therefore be used for future monitoring and audit of the burden and quality of sepsis care using MCOD data. However, regular review of the ICD-10 codes definitely or possibly associated with sepsis (and the number of deaths with these codes) would be worthwhile as ICD codes are updated. For example, a code for necrotising fasciitis, M72.6, was added by the WHO as an update to ICD-10, but not implemented for coding by ONS until 2011. As the presence of this code on a death certificate may indicate sepsis, this could be considered in future analyses, but counting deaths with one of just the three identified ICD-10 codes would still find the vast majority of sepsis-associated mortality.

Sepsis can no longer be regarded as a niche problem relevant only to the critical care units that treat the most severely affected patients. There is some evidence that recognition of sepsis may be low outside hospitals. For example, patients diagnosed with severe sepsis in one US emergency department were reviewed.25 Only half of these patients had been transported to hospital by ambulance. In this half, the paramedic had explicitly considered sepsis in only a fifth. For those patients where paramedics had recognised sepsis, there was a significant decrease in the time taken to receive antibiotic treatment. By the time patients with sepsis are admitted to critical care, they are very severely unwell and therefore likely to die despite the best efforts of their healthcare team. There is also evidence that treating patients with sepsis earlier and in a more coordinated manner reduces mortality.26 Therefore, if we could find ways to encourage earlier diagnosis and earlier, coordinated treatment, it is probable that the overall mortality from sepsis could be reduced. The reduction of sepsis-related mortality since 2007 may represent the results of the introduction of changes to identify such patients, for example, Early Warning Scoring systems, Critical Care Outreach, efforts to improve awareness and training (eg, Surviving Sepsis Campaign). However, we contend that there is clearly a room for further improvements. There is growing consensus that the clinical treatment of severely ill patients is best carried out initially in a general way, avoiding overemphasis on identifying the exact cause of sepsis. The most important element of the treatment of sepsis is to recognise whether severe illness is present and institute appropriate treatment early and rapidly (with targeted but broad spectrum antibiotics and source control) and resuscitation that aims to correct the physiological abnormalities associated with sepsis, whatever be the underlying cause. Resuscitation efforts are generic, as many elements of the sepsis syndrome are common whatever be the causal pathogen, but are important as part of the ‘bundle of care’ if mortality is to be lowered.

Despite the potential for underestimation, this study has demonstrated that sepsis is associated with 1 in 20 deaths, and therefore provides further evidence that sepsis is a major public health problem in England as well as elsewhere in the world. While there is no perfect solution to the question of how levels of sepsis-related mortality should be estimated, we hope that this result, and this method of using MCOD data, will form the basis of future accounting of the burden of sepsis among the whole population of England. These results could also support the audit of the quality of sepsis diagnosis and treatment across the whole healthcare system. Estimating sepsis-associated mortality from MCOD data (rather than estimates based on hospital patients) would also allow more detailed analyses to be undertaken, such as investigating geographic or socioeconomic inequalities in these deaths. This would be a profitable area for future research. It also allows a more nuanced debate to take place, which should now involve policy makers, public health services, primary and emergency care providers as well as critical care specialists. Ultimately, having this more detailed picture should enable improved quality of care and more cost-effective use of resources with respect to preventing, identifying and treating sepsis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DMcP, CG and MW compiled the list of ICD-10 codes to be searched. AB and EK extracted and tabulated the mortality data and calculated the death rates. All authors substantially contributed to conception and design, acquisition of the data or analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. DMcP is the guarantor.

Funding: The departments of the authors funded this study.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study is based on Multiple Cause of Death Data derived from death certificates and obtained in anonymised form only from Office for National Statistics.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.The ACCP/SCCM consensus conference committee Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use on innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest 1992;101:1481–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:530–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padkin A, Glodfrad C, Brady AR, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis occurring in the first 24 h in intensive care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2332–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edbrooke DL, Hibbert CL, Kingsley JM, et al. The patient related costs of care for sepsis patients in a UK adult general intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1999;27:1760–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talmor D, Greenberg D, Howell MD, et al. The costs and cost-effectiveness of an integrated sepsis treatment protocol. Crit Care Med 2008;36:1168–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones AE, Troyer JL, Kline JA. Cost effectiveness of an emergency department based early sepsis resuscitation protocol. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1306–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suarez D, Ferrer R, Artigas A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the surviving sepsis campaign protocol for severe sepsis: a prospective nation-wide study in Spain. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:444–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson S, Varpula M, Ruokonen E, et al. Incidence, treatment and outcome of severe sepsis in ICU-treated adults in Finland: the Finnsepsis study. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:435–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco J, Muriel-Bombin A, Sagredo V, et al. Incidence, organ dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis: a Spanish multicentre study. Critical Care 2008;12:R158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. New Engl J Med 2003;348:1546–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1303–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melamed A, Sorvillo FJ. The burden of sepsis-associated mortality in the United States from 1999 to 2005: an analysis of multiple-cause-of-death data. Crit Care 2009;13:R28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rooney C, Smith SK. Implementation of ICD-10 for mortality data in England and Wales from January 2001. Health Stat Q 2000;8:41–50 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller JH, Elford J, Goldblatt P, et al. Diabetes mortality: new light on an underestimated public health problem. Diabetologia 1983;24:336–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths C, Lamagni T, Crowcroft NS, et al. Trends in MRSA in England and Wales: analysis of morbidity and mortality data for 1993–2002. Health Stat Q 2004;21:15–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce M, Griffiths C, Brock A, et al. Trends in mortality and hospital admissions associated with epilepsy in England and Wales during the 1990's. Health Stat Q 2004;21:23–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nath U, Thomson R, Wood R, et al. Population based mortality and quality of death certification in progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:498–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths C, Rooney C. Trends in mortality from Alzheimer's Disease, Parkinson's disease and dementia in England and Wales 1979–2004. Health Stat Q 2006;30:6–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas SL, Griffiths C, Smeeth L, et al. Burden of mortality associated with autoimmune diseases among females in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2279–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organisation International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Volume 1, Tabular List World Health Organization, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organisation International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Volume 3, Alphabetical Index World Health Organization, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization ICD-10, 2007. http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/

- 23.World Health Organisation International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Volume 2, Instruction Manual World Health Organization, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office for National Statistics Mortality Statistics: Childhood Infant and Perinatal, Series DH3, No. 40. Office for National Statistics, 2009

- 25.Studnek JR, Artho MR, Garner CL, et al. The impact of emergency medical services on the ED care of severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med 2010;30:51–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The surviving sepsis campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:367–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.