Abstract

Maintaining blood glucose homeostasis is a complex process dependent on pancreatic islet hormone secretion. Hormone secretion from islets is coupled to calcium entry, which results from regenerative islet cell electrical activity. Therefore, the ionic mechanisms that regulate calcium entry into islet cells are critical to maintaining normal glucose homeostasis. Genome wide association studies have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms, including five located in or near ion channel or associated subunit genes, which show association with human diseases characterized by dysglycemia. This review focuses on polymorphisms and mutations in ion channel genes that are associated with perturbations in human glucose homeostasis and discusses their potential roles in modulating pancreatic islet hormone secretion.

Ion channels are key regulators of glucose homeostasis

Glucose sensitive cells of the pancreatic islet respond to deviations in blood glucose, with corresponding changes in transmembrane ion flux that, in turn, regulate the secretion of metabolic hormones [1–3]. High blood glucose (hyperglycemia) stimulates islet β-cell calcium entry causing insulin secretion, whereas low blood glucose (hypoglycemia) stimulates islet α-cell calcium entry resulting in glucagon secretion [1, 3–6]. Islet cell calcium influx occurs through voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs), which are regulated by glucose-induced changes in membrane potential [3–5, 7]. The membrane potential of islet cells is modulated by the orchestrated activities of potassium, sodium, chloride, and calcium channels; these ion channels are, therefore, key regulators of islet cell hormone secretion [5, 8, 9]. As the number of Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) is growing, it is becoming apparent that heritable mutations or polymorphisms in genes encoding ion channels can lead to dysregulation of islet hormone secretion and metabolic disease [10–19]. This review describes ion channel gene polymorphisms and mutations that are associated with perturbations in human glucose homeostasis and examines how they might cause dysglycemia.

KATP channels and endocrine disorders

ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels are metabolic sensors that couple glucose metabolism to cell excitability [20–22]. The KATP channel complex is an octameric assembly of four pore-forming Kir6.X (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2) subunits and four regulatory nucleotide-binding sulfonylurea receptor (SUR) subunits (SUR1, SUR2A or SUR2B) (Figure 1c, Table 1)[20–22]. In glucose sensitive cells of the pancreatic islet, KATP channels are primarily comprised of the Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) genes [20–22]. The KATP channel is sensitive to intracellular levels of ADP and ATP nucleotides; ATP inhibits the channel, via the Kir6.x subunits, whereas MgATP or MgADP stimulate the channel via the SUR subunits [21, 22]. Under high glucose conditions an increase in the ATP/ADP ratio inhibits KATP channels, whereas a decrease in this ratio during low glucose conditions leads to KATP channel activation [20, 21]. KATP channel activity influences the islet plasma membrane potential, causing membrane hyperpolarization under low glucose conditions and membrane depolarization under high glucose conditions [1, 8, 23]. Depolarization of the islet membrane activates many ion channels including VDCCs, voltage-gated sodium (NaV) channels, and potassium channels, whereas, hyperpolarization inactivates these channels [1, 3, 8, 23]. Islet cell calcium entry and hormone secretion are precisely modulated by changes in the membrane potential, thus, KATP channels play a pivotal role in coupling metabolic state and islet hormone secretion [20–22]. Therefore, mutations and polymorphisms of KATP subunit genes that perturb KATP channel function might affect glucose homeostasis and result in conditions of dysglycemia.

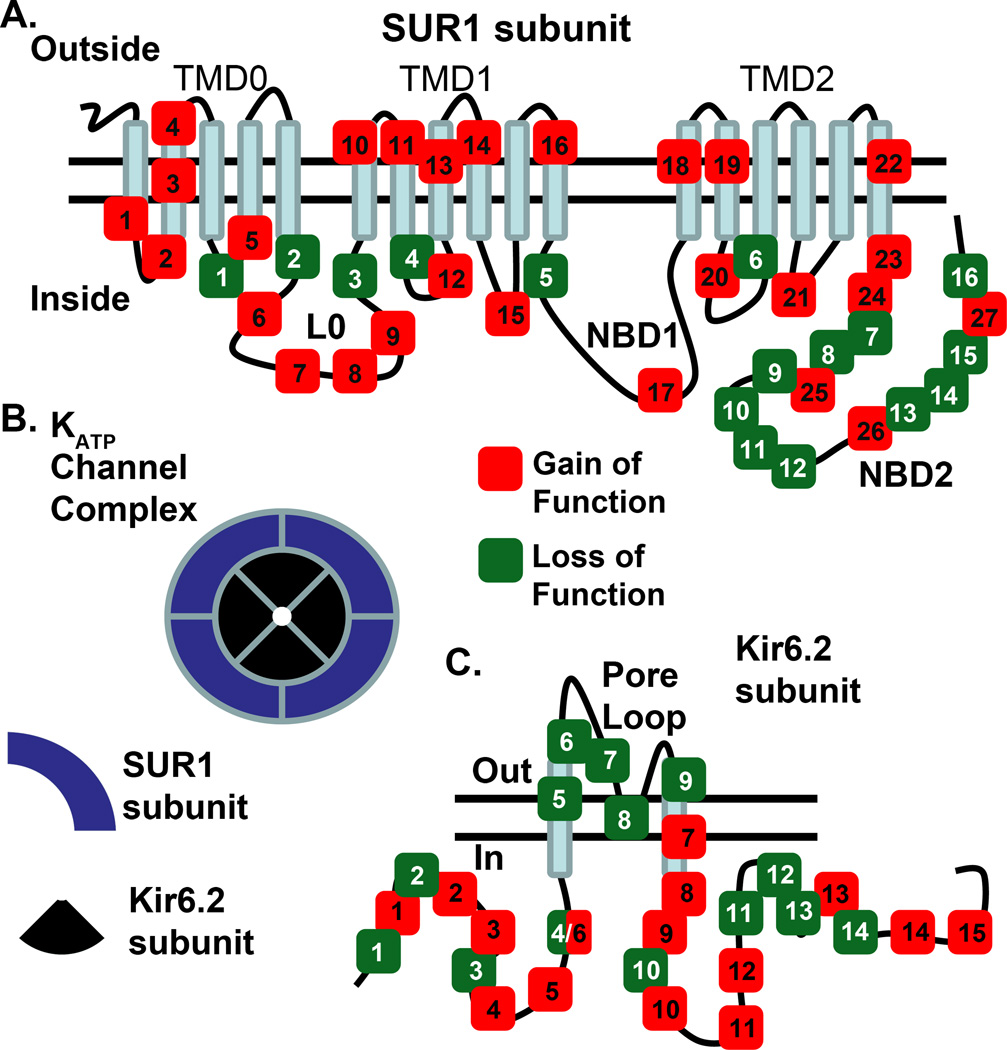

Figure 1.

Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunit mutations that result in either KATP channel gain of function or loss of function. a) Selected mutations in SUR1 that result in a KATP channel with GOF in red or LOF in green (please see table 1); TMD=transmembrane domain, L0 = intracellular linker domain, NBD1= first nucleotide binding domain, NBD2= second nucleotide binding domain . b) Diagram of a functional KATP channel complex octamer, in islet cells. The complex contains four Kir6.2 subunits and four SUR1 subunits; c) Selected mutations in Kir6.2 that result in KATP channels with either GOF in red or LOF in green (please see table 1).

Table 1.

Selected gain and loss of function (GOF and LOF) mutations of KATP channel subunits illustrated in figure 1

| SUR 1 | Kir6.2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GOF | LOF | GOF | LOF |

| 1. P45L; 2. N72S 3. V86A/G; 4. A90V |

1.H125Q | 1. F35L, F35V, G35S |

1. R34H |

| 5. F132L/V, L135P | 2. V187D | 2. H46Y, N48D | 2. G40D |

| 6. P207S, E208K, D209E, Q211K D212I/N, L213R |

3. D310N | 3. R50P, R50Q, Q52R, G53R |

3. F55L |

| 7.L225P, T229I; 8.Y263D, A269D/N |

4. R370G | 4. V59M, V59G, F60Y |

4. K67N |

| 9. R306H; 10.V324M |

5. F591L | 5. L164P | 5. W91R |

| 11. Y356C; 12. E382K |

6. T1139M | 6. I167L | 6. A101D |

| 13. C435R; L438F; 14. L451P; 15. R521Q |

7. R1353H | 7. K170T | 7. S116P |

| 16. L582V, R826W | 8. K1374R | 8. I182V | |

| 17. H1024Y; 18. T1043Q |

9. G1382S | 9. R201H | 8. G134A, R136L |

| 19. N1123D, R1153G | 10. S1386P | 10. R201C | 9. L147P |

| 20. R1183W/Q, A1185E | 11. F1388 deletion |

11. E227K, E227L, E229K |

10. A187V |

| 21. M1290V; 22. R1314H |

12. R1394H | 12. V252A | 11. P254L, H259R |

| 23. E1327K; 24. R1380C/H/L |

13. G1478V | 13. E292G, T293N, I296L |

12. P266L |

| 25. G1401R; 26. I1425V |

14. G1479R | 14. E322K | 13. E282K |

| 27. V1523A/L, V1524M, R1531A |

15. E1507; 16. R1539Q |

15. G334D | 14. R301H |

* The numbers correspond to the location of the mutations illustrated in figure 1 (normal amino acid residue, position, mutant amino acid residue).

Neonatal diabetes

The reduced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) observed in neonatal diabetic patients with mutations in KATP channel subunits, underscores the importance of KATP channels in glucose sensing [10, 12]. Two monogenic neonatal diabetic conditions that arise from KATP channel subunit gene mutations are permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus (PNDM) and transient neonatal diabetes mellitus (TNDM) [11–13]. Both forms of the disease typically present with severe hyperglycemia within the first six months of life [11, 13]. Although the majority of TNDM cases result from an imprinting defect that does not involve KATP channels, mutations in KATP genes also cause TNDM [11, 13]. To date, at least 13 mutations in the Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) subunit and 15 mutations in the SUR1 (ABCC8) subunit have been identified in patients with TNDM [11, 22] and more than 61 KCNJ11 mutations and 27 ABCC8 mutations are known to cause PNDM (Figure 1 and 2, Table 1) [12, 13]. KATP channels carrying these mutations exhibit a gain-of-function (GOF) due to a loss of regulatory inhibition by ATP [10, 21]. Thus, in TNDM or PNDM patients, glucose stimulation fails to evoke β-cell membrane excitability and insulin secretion, leaving blood glucose levels elevated (Figures 1 and 2, Tables 1 and 2) [10, 21]. Fortunately, many of these mutant channels retain sensitivity to inhibitory sulfonylurea derivatives, which interact with SUR1 to induce channel closure (BOX 1) [24, 25]. Sulfonylurea treatment of diabetics with KATP GOF mutations often results in a recovery of GSIS. Thus, oral sulfonylureas have replaced insulin injections for the majority of patients with neonatal diabetes caused by KATP mutations (Box 1) [10].

Figure 2.

Molecular architecture of a prototypical mammalian Kir6.2 potassium channel. a) Ribbon diagram of Kir6.2 tetramer modeled on the chicken Kir2.2 crystal structure (Kir6.2 alpha-subunits in red, yellow, blue, and light blue; potassium ions in green) b) Top view of the tetramer, c) Bottom view of the tetramer, and d) Ribbon diagram of two Kir6.2 subunits modeled on the Kir2.2 crystal, showing approximate location of selected Kir6.2 mutations which result in LOF (green) or GOF (red) of the KATP channel complex. The crystal structure graphics of chicken Kir2.2 (PDB code 3JYC) were generated using the UCSF Chimera package from the Computer Graphics Laboratory, University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIH P41 RR-01081) [89, 90].

Table 2.

Association of ion channel genes with aberrant islet hormone secretion

| Gene (protein) | Islet expression | Human disease association | Change in human islet function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KCNJ11 (Kir6.2) |

Beta, Alpha (human) |

Gain of function = neonatal diabetes or type-2 diabetes |

Reduced GSIS | [10–13] |

| Loss of function = hyperinsulinemia |

Glucose independent insulin secretion |

[12, 41] | ||

|

ABCC8 (SUR1) |

Beta, Alpha (human) |

Gain of function = neonatal diabetes or type-2 diabetes |

Reduced GSIS | [12, 13, 44] |

| Loss of function= hyperinsulinemia |

Glucose independent insulin secretion |

[12, 33] | ||

|

KCNJ15 (Kir4.2) |

Beta (human) |

Type-2 diabetes | Undetermined | [14] |

| KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) |

Islet (human) | Type-2 diabetes | Reduced GSIS | [15, 16, 60–62] |

|

CACNA1E (CaV2.3) |

Not found in human islets |

Type-2 diabetes | Reduced second phase GSIS | [17, 18] |

|

ABCC7 (CFTR) |

Undetermined | Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes |

Reduced GSIS | [19] |

KATP pharmacology utilized to treat diabetes.

Sulfonylureas were found to inhibit β-cell KATP currents 43 years after a treatment study for typhoid fever identified that these sulfonamide derivatives caused hypoglycemia [75, 76]. Sulfonylureas have been successfully utilized to treat diabetes since the mid-1950s [77]. The sulfonamide derivatives diazoxide and chlorothiazide were found to cause hyperglycemia, which was subsequently shown to be caused by activation of the β-cell KATP channel complex [78, 79], and have been utilized to treat hypoglycemia since the mid-1960s [80]. Sulfonamide derivatives bind to the SUR subunits of the KATP channel complex resulting in either KATP channel inhibition or activation depending on their structure [25] and remain the only KATP modulators used clinically to regulate insulin secretion.

Although sulfonylureas induce β-cell insulin secretion primarily via KATP channel inhibition, they may also act through KATP independent mechanism(s) to modulate GSIS [81–83]. For example, SUR1 deficient mouse β-cells show enhanced GSIS in the presence of tolbutamide, thus, implicating a non-KATP induced mechanism of sulfonylurea action [83]. One mechanism that has been implicated in SUR1-independent regulation of mouse GSIS by sulfonylureas is their activation of the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac2) [81–83]. However, recent reports fail to replicate activation of rodent Epac2 by sulfonylureas [84, 85]. Therefore, addressing if sulfonylureas regulate human β-cell GSIS independently of SUR1 should be determined. Interestingly, SUR1 also regulates mouse insulin granule priming, which enhances GSIS independently from its interactions with Kir6.2 [83, 86]. Thus, it is important to assess if any human SUR1 mutations, which result in dysglycemia, modulate human insulin granule priming independently of KATP. The mechanisms responsible for the KATP-independent modulation of GSIS by sulfonylureas and SUR1 subunits are important pathways with potential therapeutic implications for diabetes. However, closure of KATP channels by sulfonylureas is the primary mechanism for increasing GSIS in diabetic patients [20, 21].

Sulfonamide derivatives restore euglycemia in a majority of patients with KATP channel mutations; however, some of the conditions caused by these mutations are not rescued with sulfonamide derivative treatment [26, 40, 87]. Sulfonamide derivative resistant KATP channel mutations are associated with dysglycemia. Furthermore, sulfonylurea treatment does not completely rescue the mental deficits caused by certain GOF KATP mutations [26, 87]. Therefore, potent and selective Kir6.2 activators or inhibitors might provide a therapeutic option for treating sulfonamide derivative resistant dysglycemia and sulfonylurea resistant mental deficits caused by KATP mutations [88].

Some neonatal diabetic patients also show evidence of severe nervous system impairment. Two mutations in the ABCC8 gene and more than 15 mutations in KCNJ11 have been associated with a syndrome characterized by developmental delay, epilepsy, and neonatal diabetes (DEND) [12, 26]. The resulting KATP channels exhibit greater GOF properties than those causing PNDM or TNDM [27]. Since Kir6.2 and SUR1 are expressed in the nervous system, it is possible that overactive KATP channels in neurons may explain some of the clinical manifestations of DEND syndrome [28, 29]. However, diabetes in DEND patients is primarily caused by a significant reduction of β-cell GSIS similar to TNDM and PNDM [12, 26]. Therefore, insulin injections or oral sulfonylureas are utilized to treat the diabetes phenotype of DEND syndrome (Box1) [26].

Studies of the KATP channels causing PNDM, TNDM and DEND reveal insights into the molecular and biophysical mechanisms underlying neonatal diabetes [12, 30]. Four general GOF mechanisms have been described to date: 1) Increased open probability of KATP channels which reduces the ability of ATP to inhibit channel activity (Figure 2) [31]; 2) Decreased affinity of ATP for the KATP channel [32]; 3) Increased Mg-nucleotide activation of KATP channels (due to SUR1 nucleotide binding domain (NBD) mutations) [33]; and 4) Defective transduction between ATP binding and channel closure [27] (Figure 1 and 2, Table 1). Many of the mutations which cause KATP channel GOF reside in protein domains that regulate channel function (Figures 1 and 2, Tables 1 and 2) and these include: 1) the Kir6.2 ATP binding domain [34]; 2) the SUR1 Mg-ATP and MgADP NBDs [35]; 3) the SUR1 ATPase domain [21]; 4) Kir6.2 (Q52 and V59) and SUR1 gating domains (F132) [36, 37]; and 5) domains that transduce nucleotide binding to Kir6.2 channel opening (such as the cytoplasmic loop L0 between transmembrane domains TMD0 and TMD1 of SUR1) [33, 38]. Future analysis of additional KATP GOF mutations will enhance our understanding of how the KATP channel complex is regulated by glucose.

Hyperinsulinemia

Mutations in KATP subunit genes that result in a loss of channel function lead to hyperinsulinemia of infancy (HI) [21, 39]. Over 150 mutations in ABCC8 and more than 25 mutations in KCNJ11 are known to cause HI, and new mutations continue to be identified (Figures 1 and 2, Tables 1 and 2) [12]. Most cases of persistent HI are caused by autosomal recessive KATP mutations, whereas autosomal dominant transmission of HI occurs with only 24 ABCC8 mutations and 3 KCNJ11 mutations [40, 41]. Patients with HI caused by recessive KATP mutations tend to present with greater plasma insulin levels earlier in life than patients with dominant KATP mutations [40, 41]. In contrast to the β-cell membrane hyperpolarization caused by GOF mutations, loss of function (LOF) mutations in KATP lead to membrane depolarization, constitutive calcium entry, and excessive insulin secretion (Figures 1 and 2, Tables 1 and 2) [30]. These mutations reduce KATP channel activity by: 1) Introduction of a premature stop codon, resulting in a nonfunctional channel [12, 42]; 2) Reducing the ability of MgADP to activate of the KATP channel complex (these mutations cluster near the second of the two NBDs of SUR1 (NBD2), Figure 1, Table 1) [33]; and 3) Reduced trafficking of the KATP channel complex to the plasma membrane [41]. Importantly, the hypoglycemia associated with most dominantly transmitted cases of HI can be treated with the KATP channel openers diazoxide and chlorothiazide (Box1) [43]. Non-responders typically require partial pancreatectomy surgery to improve their blood glucose levels [30, 43].

Type-2 diabetes

Polymorphisms in the KATP channel subunit genes ABCC8 and KCNJ11 have also been associated with increased risk of developing type-2 diabetes [44, 45]. Two polymorphisms that show strong linkage disequilibrium and therefore segregate together include a polymorphism in KCNJ11 (exon 18, codon 23, T/C) resulting in E23K (glutamate 23 to lysine substitution) and a polymorphism of ABCC8 (exon 33, codon 1369, T/G) resulting in S1369A (serine 1369 to alanine substitution) [45]. Large association studies suggest that linkage of these polymorphisms with type-2 diabetes occurs in the homozygous state [46, 47]. The E23K and S1369A variants lead to a modest gain in KATP channel function, in vitro, however, the exact mechanism of increased KATP channel activity is controversial [22, 48, 49]. Development of type-2 diabetes is, therefore, presumably influenced by age related factors that exacerbate the slight GOF in KATP channel activity induced by these variants [50].

The E23K and S1369A variants of KATP channel subunits have been associated with a reduction in GSIS, which may increase the risk of developing type-2 diabetes [49, 51, 52]. Impaired GSIS might result from the slight increase in β-cell KATP channel activity, which would reduce glucose stimulated β-cell calcium influx and insulin secretion [22, 48, 49]. However, reduced GSIS caused by the E23K and S1369A variants does not lead to significant hyperglycemia early in life; thus, decreased insulin secretion is compensated for, possibly through increased insulin sensitivity [49]. Aging related changes in metabolism may exacerbate the slight increase in KATP channel activity observed with these two variants and cause a further diminution of GSIS [50]. Obesity or insulin resistance could also exacerbate the reduction in GSIS observed in carriers of the E23K and S1369A variants [49, 51]. Therefore, one may speculate that a small decrease in GSIS may predispose carriers of E23K and S1369A variants to type-2 diabetes when combined with other factors that reduce either insulin secretion or insulin sensitivity [49, 51]. However, carriers of these variants do not always show reduced GSIS; thus, other KATP associated mechanisms may influence the progression of type-2 diabetes [53, 54].

The E23K and S1369A variants of KATP channel subunits have also been associated with aberrant glucose-induced inhibition of glucagon secretion [54]. This may result from a direct role of KATP channel activity regulating human glucagon secretion from α-cells [5, 6, 55]. The putative mechanism responsible for the KATP regulation of glucagon secretion has to do with VDCC activity [5, 55]. Calcium entry through VDCCs is essential for human α-cell glucagon secretion and is elevated under low glucose conditions as well as by KATP activation [6, 56]. Membrane depolarization activates α-cell VDCCs, however, these channels become inactivated if depolarization persists [6, 7]. Human α-cell depolarization induced with KATP inhibition results in significant inactivation of the VDCCs, which reduces α-cell calcium influx and glucagon secretion [5, 6], whereas activation of KATP channels under low glucose conditions results in membrane polarization to a level that sustains significant VDCC activity, calcium entry and glucagon secretion [5, 6]. Thus, the KATP channel GOF variants E23K and S1369A may reduce α-cell depolarization induced inactivation of VDCCs under high glucose conditions, which would increase calcium influx and glucagon secretion [6, 54, 55]. The resulting increase in hepatic glucose output combined with reduced GSIS in carriers of these variants could increase the risk of developing hyperglycemia and type-2 diabetes. However, only a small number of studies have implicated KATP in regulating human α-cell glucagon secretion [5, 6, 54, 55]. Future studies will improve the understanding of the role KATP channels play in regulating glucagon secretion.

KATP channel activity might also regulate α-cell glucagon secretion indirectly, through control of paracrine signals released by β-cells. Paracrine signals such as insulin, γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA], or Zn2+ ions, are released from β-cells in a glucose-dependent manner and modulate α-cell glucagon release [4, 57]. The exact paracrine signals that influence human islet glucagon secretion are controversial; however, aberrant GSIS caused by type-1 and type-2 diabetes leads to dysregulated α-cell glucagon secretion [6, 57]. Thus, alterations in GSIS and β-cell paracrine signaling that occur with KATP channel variants, such as E23K and S1369A, may also influence glucagon secretion [55, 57]. However, the exact role that human KATP mutations and polymorphisms play in modulating human glucagon secretion via islet cell paracrine signaling is still being determined [57].

Non-KATP ion channels associated with diabetic conditions

Type-2 diabetes and KCNJ15 polymorphisms

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the KCNJ15 gene encoding the inward rectifier potassium channel Kir4.2 (Table 2) are associated with type-2 diabetes [14]. The SNPs are located in exon 4 of the KCNJ15 and are specifically associated with the development of lean type-2 diabetes in the Japanese population [14]. Kir4.2 expression has been identified in human pancreatic β-cells and Kir4.2 potassium channel activity, similar to that of KATP, is predicted to polarize the β-cell membrane and thus antagonize the ability of the β-cell to depolarize in response to glucose [14, 58]. One of the KCNJ15 SNPs associated with type-2 diabetes, rs3746876 (T), increases Kir4.2 mRNA stability in human peripheral blood cells [14]; an observation that has led to the speculation that increased Kir4.2 channel transcript stability and density in β-cells may limit insulin secretion during the progression of diabetes [14]. However, this preliminary work requires confirmation in human β-cells to determine the potential role of Kir4.2 during GSIS. Future studies will also determine if Kir4.2 channel activity in other glucose sensitive tissues influences glucose homeostasis or if KCNJ15 polymorphisms regulate nearby genes that modulate the progression of type-2 diabetes.

Type-2 diabetes and KCNQ1 polymorphisms

Polymorphisms in KCNQ1, which encodes a voltage-gated delayed rectifier potassium channel, Kv7.1, are associated with type-2 diabetes (Table 2). The most significant association with type-2 diabetes occurs with carriers of the KCNQ1 SNP rs2237892 (C) in intron 15 [15]. Mutations in the KCNQ1 gene (also known as KvLQT1) cause perturbations in cardiac tissue action potential repolarization during contraction, causing a syndrome termed long QT (the interval between the Q wave and T wave of an electrocardiogram recording), an observation that underscores the important role Kv7.1 channels play in regulating membrane repolarization of cardiac cells [59]. However, mutations in Kv7.1 that result in long QT syndrome do not predispose these subjects to diabetes [15, 16, 60]. How polymorphisms in KCNQ1 associate with type-2 diabetes is currently being determined and three independent potential mechanisms have recently emerged [61–64].

One mechanism implicates a role of KCNQ1 polymorphisms in decreasing islet insulin secretion. Human islets isolated from nondiabetic donors with and without the KCNQ1 SNP, rs2237892 (C) were analyzed for insulin secretion [61]. Islets from carriers of the diabetic-associated KCNQ1 SNP, rs2237892 (C), obtained from the Nordic network for clinical islets, showed significantly reduced GSIS compared with controls, despite equivalent levels of KCNQ1 mRNA [61]. Although these data suggest a role for human islet Kv7.1 channels in regulating islet insulin secretion, human β-cells have little to no endogenous Kv7.1 current [8]. Therefore, the rs2237892 (C) SNP may influence insulin secretion through signaling from a glucose sensitive cell other than the β-cell.

The KCNQ1 SNP, rs2237892 (C) has been implicated in modulating GSIS indirectly from pancreatic islets through perturbations in glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) levels [62]. A study of a German cohort has suggested that oral GSIS, which is dependent on intestinal incretin secretion, is significantly impaired in subjects carrying the rs151290 (C) SNP [62]. L-cells of the intestine secrete the incretin GLP-1 in response to oral glucose stimulation, thus, L-cells may be regulated by Kv7.1 channel activity. Although Kv7.1 expression in human L-cells has not been determined, mouse L-cells express significant amounts of Kv7.1 [65]. Subjects with the type-2 diabetes associated KCNQ1 SNP rs151290 (C) also have significantly reduced GLP-1 levels in response to oral glucose, compared with controls [62]. Therefore, Kv7.1 channel activity may regulate L-cell GLP-1 secretion and thus influence GSIS from the β-cell. Although changes in Kv7.1 channel activity or expression could predispose carriers of the KCNQ1 SNP rs151290 (C) to diabetes, there is currently no evidence that this polymorphism regulates Kv7.1 channel activity. Another possibility is that the KCNQ1 SNP rs151290 (C) does not influence Kv7.1 but instead influences DNA signaling from the KCNQ1 locus, which could regulate secondary gene expression and influence glucose homeostasis.

A DNA signaling perturbation of an imprinting domain located in intron 10 of KCNQ1 has been implicated in linking KCNQ1 polymorphisms to type-2 diabetes [63, 64]. The KCNQ1 gene is itself imprinted and harbors an imprinting control element that influences neighboring gene expression [66, 67]. Thus, polymorphisms near the KCNQ1 imprinting control element may lead to aberrant expression of the genes that it influences in a parent-of-origin specific manner. Evidence for this has been established by looking at the heritability of type-2 diabetes association with KCNQ1 SNPs [63]. Interestingly, significant association of KCNQ1 SNPs rs2237892 (C) or rs231362 (C) with type-2 diabetes occurs only when maternally transmitted [63]. Therefore, perturbed imprinting in the KCNQ1 gene locus may result in diabetes through influences on secondary gene expression that regulate glucose homeostasis [66, 67]. For example, the KCNQ1 gene locus has been shown to influence expression of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), thus, dysregulation of IGF2 expression by KCNQ 1 polymorphisms may lead to aberrant islet cell development and function [66–68]. Future studies will determine differences in the expression of genes that are impacted by polymorphisms in the KCNQ1 imprinting control region and how they affect progression of type-2 diabetes.

Type-2 diabetes and CACNA1E polymorphisms

Polymorphisms of the human CACNA1E gene, which encodes the VDCC CaV2.3, are associated with the development of type-2 diabetes (Table 2) [17, 18]. Two association studies, one done on a Swedish and Botnia prospective cohort, and one done with a Pima Indian cohort identified strong association of SNPs within the CACNA1E gene, with type-2 diabetes [17, 18]. Carriers of the SNP rs679931 (TT) in CACNA1E show reductions in both intravenous and oral glucose tolerance as well as a diminished 2nd phase GSIS [17]. Although these data suggest a possible involvement of CaV2.3 in human GSIS during the progression of type-2 diabetes, other data show 1) no detectable expression of CaV2.3 mRNA in human islets [8] and 2) that human β-cells VDCC currents are not inhibited by a potent and specific peptide inhibitor of CaV2.3 [8]. Therefore, the role for CaV2.3 in regulating human islet insulin secretion is unclear. One may speculate that human CaV2.3 channel activity plays a more prominent role influencing β-cell insulin secretion when insulin demand is increased and blood glucose levels are elevated during the progression of type-2 diabetes. Future studies will determine if the CACNA1E SNP rs679931 (TT) modulates the expression or function of human CaV2.3, which glucose sensitive cells CaV2.3 influences and how this modulates human glucose homeostasis.

Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes

Mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), which cause cystic fibrosis (CF), can perturb islet cell function and result in diabetes. The first description of CF in 1938 described pancreatic fibrosis and its relation to celiac disease [69]. Almost all CF patients show exocrine tissue damage in the pancreas due to impairments in pancreatic duct epithelium salt and water transport. Although exocrine pancreas damage may influence the development of cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD), some CF patients develop diabetes in the first decade of life indicating that CFRD may be a condition coincident with exocrine disease [70]. CFRD results in part from a reduction in pancreatic β-cell number and function leading to decreased GSIS [71]. CFTR is an important anion channel that regulates epithelial cell function, however, a role for CFTR in human islet hormone secretion as well as its expression in human β-cells is not known and should be determined. Three possible mechanisms for CFRD-induced reduction of insulin secretion have emerged: 1) Mutant CFTR induces severe pancreas pathology resulting in β-cell stress and reduced β-cell number and function [19]; 2) Mutant CFTR expression in the β-cell induces ER stress, accounting for reduced β-cell function [19, 72]; and 3) CFTR expression in the human anterior hypothalamus regulates glucose sensitive neuron excitability [73], which may perturb insulin secretion. The exact mechanism of how mutations in CFTR reduce human islet function remains to be determined. Future studies using specific channel inhibitors will begin to address how CFTR regulates hormone secretion from human islet cells [74].

Conclusions

The orchestrated activity of functionally diverse ion channels regulates islet cell calcium entry, which is influenced by blood glucose levels and coupled to islet hormone secretion. The importance of ion channels in maintaining glucose homeostasis has become clear with the identification of heritable mutations and polymorphisms in ion channel encoding genes that alter glucose regulated islet hormone secretion. Currently mutations or polymorphisms in or near the genes of five ion channels have been associated with human conditions that show aberrant islet hormone secretion. More are certain to follow. However, there is a virtual continuum of metabolic conditions with overlapping symptoms resulting from defects in islet hormone secretion, making it difficult to pinpoint metabolic conditions caused by individual gene mutations. Ongoing studies utilizing new technologies such as exome and whole-genome sequencing, coupled with conventional methods in electrophysiology and imaging, should yield exciting new insights into the functions of ion channels in the regulation of islet hormone secretion. This work will lead to novel therapeutic strategies for fighting diabetes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K01 DK081666-02, DAJ; and R01 DK082884-01, JSD).

Glossary

- Action Potential

a brief depolarization of the membrane potential.

- Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)

an ATP dependent plasma membrane transporter of chloride and thiocyanate.

- Developmental delay, epilepsy, and neonatal diabetes (DEND)

a syndrome caused by significant overactivity of KATP channels.

- Hyperinsulinemia (HI)

a condition characterized by excessive insulin secretion, which is commonly associated with mutations that decrease KATP channel activity.

- KATP Gain of Function (GOF)

Mutation in a KATP subunit gene that results in increased activity of the KATP channel complex.

- KATP Loss of Function (LOF)

mutation in a KATP subunit gene that results in decreased activity of the KATP channel complex.

- Nucleotide Binding Domain (NBD)

protein motifs that bind nucleotides such as ATP, MgATP, or MgADP.

- Permanent Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus (PNDM)

a monogenic form of diabetes that typically develops within the first six months of life.

- Transient Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus (TNDM)

a type of diabetes that develops shortly after birth preceding normal glycemia in infancy; some TNDM patients (~50%) become hyperglycemic again later in life.

- Voltage Dependent Calcium Channel (VDCC)

calcium channels that are activated by membrane depolarization.

Contributor Information

Jerod Scott Denton, Departments of Anesthesiology and Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, 37232, USA.

David Aaron Jacobson, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, 37232, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henquin JC, et al. Nutrient control of insulin secretion in isolated normal human islets. Diabetes. 2006;55:3470–3477. doi: 10.2337/db06-0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun M, et al. Exocytotic properties of human pancreatic beta-cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1152:187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drews G, et al. Electrophysiology of islet cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;654:115–163. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gromada J, et al. Alpha-cells of the endocrine pancreas: 35 years of research but the enigma remains. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:84–116. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramracheya R, et al. Membrane potential-dependent inactivation of voltage-gated ion channels in alpha-cells inhibits glucagon secretion from human islets. Diabetes. 2010;59:2198–2208. doi: 10.2337/db09-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald PE, et al. A K ATP channel-dependent pathway within alpha cells regulates glucagon release from both rodent and human islets of Langerhans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang SN, Berggren PO. The role of voltage-gated calcium channels in pancreatic beta-cell physiology and pathophysiology. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:621–676. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun M, et al. Voltage-gated ion channels in human pancreatic beta-cells: electrophysiological characterization and role in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.2337/db07-0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun M, et al. Somatostatin release, electrical activity, membrane currents and exocytosis in human pancreatic delta cells. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1566–1578. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1382-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gloyn AL, et al. Activating mutations in the gene encoding the ATP-sensitive potassium-channel subunit Kir6.2 and permanent neonatal diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1838–1849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flanagan SE, et al. Mutations in ATP-sensitive K+ channel genes cause transient neonatal diabetes and permanent diabetes in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2007;56:1930–1937. doi: 10.2337/db07-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flanagan SE, et al. Update of mutations in the genes encoding the pancreatic beta-cell K(ATP) channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and sulfonylurea receptor 1 (ABCC8) in diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinism. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:170–180. doi: 10.1002/humu.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greeley SA, et al. Update in neonatal diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17:13–19. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328334f158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto K, et al. Identification of KCNJ15 as a susceptibility gene in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasuda K, et al. Variants in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1092–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voight BF, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:579–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmkvist J, et al. Polymorphisms in the gene encoding the voltage-dependent Ca(2+) channel Ca (V)2.3 (CACNA1E) are associated with type 2 diabetes and impaired insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2467–2475. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller YL, et al. Variants in the Ca V 2.3 (alpha 1E) subunit of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels are associated with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 2007;56:3089–3094. doi: 10.2337/db07-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali BR. Is cystic fibrosis-related diabetes an apoptotic consequence of ER stress in pancreatic cells? Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McTaggart JS, et al. The role of the KATP channel in glucose homeostasis in health and disease: more than meets the islet. J Physiol. 2010;588:3201–3209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Remedi MS, Koster JC. K(ATP) channelopathies in the pancreas. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:307–320. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0756-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnett DW, et al. Voltage-dependent Na+ and Ca2+ currents in human pancreatic islet beta-cells: evidence for roles in the generation of action potentials and insulin secretion. Pflugers Arch. 1995;431:272–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00410201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sturgess NC, et al. Effects of sulphonylureas and diazoxide on insulin secretion and nucleotide-sensitive channels in an insulin-secreting cell line. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;95:83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb16551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trube G, et al. Opposite effects of tolbutamide and diazoxide on the ATP-dependent K+ channel in mouse pancreatic beta-cells. Pflugers Arch. 1986;407:493–499. doi: 10.1007/BF00657506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zwaveling-Soonawala N, et al. Successful transfer to sulfonylurea therapy in an infant with developmental delay, epilepsy and neonatal diabetes (DEND) syndrome and a novel ABCC8 gene mutation. Diabetologia. 2011;54:469–471. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1981-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proks P, et al. A gating mutation at the internal mouth of the Kir6.2 pore is associated with DEND syndrome. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:470–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langmann T, et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR expression profiling of the complete human ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily in various tissues. Clin Chem. 2003;49:230–238. doi: 10.1373/49.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miki T, et al. The structure and function of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in insulin-secreting pancreatic beta-cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999;22:113–123. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0220113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols CG, et al. Adenosine diphosphate as an intracellular regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1996;272:1785–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mannikko R, et al. Interaction between mutations in the slide helix of Kir6.2 associated with neonatal diabetes and neurological symptoms. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:963–972. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koster JC, et al. DEND mutation in Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) reveals a flexible N-terminal region critical for ATP-sensing of the KATP channel. Biophys J. 2008;95:4689–4697. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.138685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Q, et al. Neonatal Diabetes Caused by Mutations in Sulfonylurea Receptor 1: Interplay between Expression and Mg-Nucleotide Gating Defects of ATP-Sensitive Potassium Channels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trapp S, et al. Identification of residues contributing to the ATP binding site of Kir6.2. EMBO J. 2003;22:2903–2912. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguilar-Bryan L, et al. Cloning of the beta cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koster JC, et al. ATP and sulfonylurea sensitivity of mutant ATP-sensitive K+ channels in neonatal diabetes: implications for pharmacogenomic therapy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2645–2654. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proks P, et al. Molecular basis of Kir6.2 mutations associated with neonatal diabetes or neonatal diabetes plus neurological features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17539–17544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404756101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan KW, et al. N-terminal transmembrane domain of the SUR controls trafficking and gating of Kir6 channel subunits. EMBO J. 2003;22:3833–3843. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas PM, et al. Mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor gene in familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Science. 1995;268:426–429. doi: 10.1126/science.7716548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macmullen CM, et al. Diazoxide-unresponsive congenital hyperinsulinism in children with dominant mutations of the beta-cell sulfonylurea receptor SUR1. Diabetes. 2011;60:1797–1804. doi: 10.2337/db10-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinney SE, et al. Clinical characteristics and biochemical mechanisms of congenital hyperinsulinism associated with dominant KATP channel mutations. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2877–2886. doi: 10.1172/JCI35414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hugill A, et al. A mutation in KCNJ11 causing human hyperinsulinism (Y12X) results in a glucose-intolerant phenotype in the mouse. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2352–2356. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1866-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palladino AA, Stanley CA. A specialized team approach to diagnosis and medical versus surgical treatment of infants with congenital hyperinsulinism. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2011;20:32–37. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inoue H, et al. Sequence variants in the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR) gene are associated with NIDDM in Caucasians. Diabetes. 1996;45:825–831. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.6.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakura H, et al. Sequence variations in the human Kir6.2 gene, a subunit of the beta-cell ATP-sensitive K-channel: no association with NIDDM in while Caucasian subjects or evidence of abnormal function when expressed in vitro. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1233–1236. doi: 10.1007/BF02658512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hani EH, et al. Missense mutations in the pancreatic islet beta cell inwardly rectifying K+ channel gene (KIR6.2/BIR): a meta-analysis suggests a role in the polygenic basis of Type II diabetes mellitus in Caucasians. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1511–1515. doi: 10.1007/s001250051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gloyn AL, et al. Large-scale association studies of variants in genes encoding the pancreatic beta-cell KATP channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) confirm that the KCNJ11 E23K variant is associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:568–572. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwanstecher C, et al. K(IR)6.2 polymorphism predisposes to type 2 diabetes by inducing overactivity of pancreatic beta-cell ATP-sensitive K(+) channels. Diabetes. 2002;51:875–879. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villareal DT, et al. Kir6.2 variant E23K increases ATP-sensitive K+ channel activity and is associated with impaired insulin release and enhanced insulin sensitivity in adults with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 2009;58:1869–1878. doi: 10.2337/db09-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riedel MJ, et al. Current status of the E23K Kir6.2 polymorphism: implications for type-2 diabetes. Hum Genet. 116:133–145. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nielsen EM, et al. The E23K variant of Kir6.2 associates with impaired post-OGTT serum insulin response and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:573–577. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Florez JC, et al. Haplotype structure and genotype-phenotype correlations of the sulfonylurea receptor and the islet ATP-sensitive potassium channel gene region. Diabetes. 2004;53:1360–1368. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.t Hart LM, et al. Variations in insulin secretion in carriers of the E23K variant in the KIR6.2 subunit of the ATP-sensitive K(+) channel in the beta-cell. Diabetes. 2002;51:3135–3138. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tschritter O, et al. The prevalent Glu23Lys polymorphism in the potassium inward rectifier 6.2 (KIR6.2) gene is associated with impaired glucagon suppression in response to hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2002;51:2854–2860. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rorsman P, et al. K(ATP)-channels and glucose-regulated glucagon secretion. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quoix N, et al. Glucose and pharmacological modulators of ATP-sensitive K+ channels control [Ca2+]c by different mechanisms in isolated mouse alpha-cells. Diabetes. 2009;58:412–421. doi: 10.2337/db07-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unger RH, Orci L. Paracrinology of islets and the paracrinopathy of diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010:16009–16012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006639107. (2010/08/28 edn) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shuck ME, et al. Cloning and characterization of two K+ inward rectifier (Kir) 1.1 potassium channel homologs from human kidney (Kir1.2 and Kir1.3) J Biol Chem. 1997;272:586–593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1205–1253. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan JT, et al. Polymorphisms identified through genome-wide association studies and their associations with type 2 diabetes in Chinese, Malays, and Asian-Indians in Singapore. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:390–397. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jonsson A, et al. A variant in the KCNQ1 gene predicts future type 2 diabetes and mediates impaired insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2009;58:2409–2413. doi: 10.2337/db09-0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mussig K, et al. Association of type 2 diabetes candidate polymorphisms in KCNQ1 with incretin and insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2009;58:1715–1720. doi: 10.2337/db08-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kong A, et al. Parental origin of sequence variants associated with complex diseases. Nature. 2009;462:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature08625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCarthy MI. Casting a wider net for diabetes susceptibility genes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1039–1040. doi: 10.1038/ng0908-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dedek K, Waldegger S. Colocalization of KCNQ1/KCNE channel subunits in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:896–902. doi: 10.1007/s004240100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee MP, et al. Human KVLQT1 gene shows tissue-specific imprinting and encompasses Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 1997;15:181–185. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smilinich NJ, et al. A maternally methylated CpG island in KvLQT1 is associated with an antisense paternal transcript and loss of imprinting in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8064–8069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rabinovitch A, et al. Insulin and multiplication stimulating activity (an insulin-like growth factor) stimulate islet (beta-cell replication in neonatal rat pancreatic monolayer cultures. Diabetes. 1982;31:160–164. doi: 10.2337/diab.31.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andersen DH. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathologic study. Am J Dis Child. 1938;56:344–399. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lombardi F, et al. Diabetes in an infant with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Diabetes. 2004;5:199–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Soejima K, Landing BH. Pancreatic islets in older patients with cystic fibrosis with and without diabetes mellitus: morphometric and immunocytologic studies. Pediatr Pathol. 1986;6:25–46. doi: 10.3109/15513818609025923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ntimbane T, et al. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: from CFTR dysfunction to oxidative stress. Clin Biochem Rev. 2009;30:153–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mulberg AE, et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression in human hypothalamus. Neuroreport. 1998;9:141–144. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199801050-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tradtrantip L, et al. Nanomolar potency pyrimido-pyrrolo-quinoxalinedione CFTR inhibitor reduces cyst size in a polycystic kidney disease model. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6447–6455. doi: 10.1021/jm9009873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Janbon M, CJ, Vedel A, Schaap J. Accidents hypoglycémiques graves par un sulfamidothiadiazol (le VK 57 ou 2254 RP) Montpellier Med. 1942;441:21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sturgess NC, et al. The sulphonylurea receptor may be an ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Lancet. 1985;2:474–475. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Franke H, Fuchs J. A new anti-diabetes principle; results of clinical research. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1955;80:1449–1452. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1116221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Inagaki N, et al. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loubatieres A. A.: Analyse du mecanisme de l'action hypoglycemiante du p-amino-benzene-sulfamido-isopropylthiodiazol. Comp. Rend. Soc. Biol. 1944;138:766–767. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Black J. Diazoxide and the treatment of hypoglycemia: an historical review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;150:194–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb19045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang CL, et al. The cAMP sensor Epac2 is a direct target of antidiabetic sulfonylurea drugs. Science. 2009;325:607–610. doi: 10.1126/science.1172256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herbst KJ, et al. Direct activation of Epac by sulfonylurea is isoform selective. Chem Biol. 2011;18:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eliasson L, et al. SUR1 regulates PKA-independent cAMP-induced granule priming in mouse pancreatic B-cells. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leech CA, et al. Facilitation of ss-cell K(ATP) channel sulfonylurea sensitivity by a cAMP analog selective for the cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor Epac. Islets. 2010;2:72–81. doi: 10.4161/isl.2.2.10582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tsalkova T, et al. Exchange protein directly activated by cyclic AMP isoform 2 is not a direct target of sulfonylurea drugs. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2011;9:88–91. doi: 10.1089/adt.2010.0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eliasson L, et al. PKC-dependent stimulation of exocytosis by sulfonylureas in pancreatic beta cells. Science. 1996;271:813–815. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Slingerland AS, et al. Improved motor development and good long-term glycaemic control with sulfonylurea treatment in a patient with the syndrome of intermediate developmental delay, early-onset generalised epilepsy and neonatal diabetes associated with the V59M mutation in the KCNJ11 gene. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2559–2563. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hansen JB. Towards selective Kir6.2/SUR1 potassium channel openers, medicinal chemistry and therapeutic perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:361–376. doi: 10.2174/092986706775527947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tao X, et al. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic strong inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2 at 3.1 A resolution. Science. 2009;326:1668–1674. doi: 10.1126/science.1180310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]