Abstract

A proposed immune mechanism that potentially modifies or exacerbates neurodegenerative disease presentation in older adults has received considerable attention in the past decade, with recent studies demonstrating a strong link between pro-inflammatory markers and neurodegeneration. The overarching aim of the following review is to synthesize recent research that supports a possible relationship between inflammation and clinical features of neurodegenerative diseases, including risk of development, cognitive and clinical correlates, and progression of the specified diseases. Specific emphasis is placed on providing a temporal context for the association between inflammation and neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Inflammation, Cognition, Neuropsychology, Neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer’s

The age-associated dysregulation of the immune system is a well-established finding, and may contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Although an interface between inflammation and dementia has received considerable empirical support, the mechanisms by which inflammation might impact cognition and neurodegeneration remain poorly understood. Of particular importance is the temporal link between inflammation and cognitive decline, as knowing when inflammation affects clinical presentation is critical for determining the point at which anti-inflammatory interventions might be most beneficial. Thus, while it is important to isolate patterns of inflammatory markers that discriminate between neurodegenerative diseases and healthy older adults, a more pressing issue is to identify how inflammation affects patients’ clinical presentation and when inflammation exerts its most deleterious impact.

The purpose of this paper is to review research findings that address how inflammatory markers might affect risk for cognitive decline, progression of disease, and cognitive presentation in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Frontotemporal dementia. In this review, we utilize a model that explores the temporal relationship between inflammatory markers and the clinical manifestation of neurodegenerative diseases. Considering that inflammatory markers might represent both precipitating and reactionary responses to neurodegeneration, the time course and specific cognitive processes involved in the immune cascade are carefully considered.

INFLAMMATORY MECHANISMS OF NEURODEGENERATION

Inflammatory processes represent a normal response to pathogen invasion that are critical for initiating tissue repair, upholding basal cognitive functions, and maintaining homeostatic function (Giunta, 2008). However, sustained neuroinflammation has injurious effects on neurological functioning that can disrupt cognition and affect neurodegeneration. The extant literature on inflammation and neurodegeneration suggests that while inflammation was initially conceptualized as solely a secondary effect of protein accumulation and neuronal death, it is now thought to be a relatively early event that interacts with and potentially precedes evidence of neurodegeneration (Hoozemans, Veerhuis, Rozemuller, & Eikelenboom, 2006; Schuitemaker et al., 2009).

The complex and at times paradoxical role of inflammation is evident, albeit poorly understood, in neurodegenerative diseases. At an undetermined stage in the disease process, an inflammatory response is mounted to facilitate clearance of abnormal protein aggregates and dying neurons in the brain, thereby participating in a coordinated attempt to remove altered cells. Although pro-inflammatory, this response can be couched as a beneficial mechanism that attempts to circumvent further neuronal degradation. However, part and parcel of the inflammatory response is the generation of inflammatory mediators, such as acute-phase proteins (e.g., C-reactive protein), chemokines (e.g., MCH-1), and cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, Interleukin-6, Interleukin-1β), which can engender toxic effects on neuronal function and further stimulate abnormal protein synthesis if chronically sustained (Wyss-Coray & Mucke, 2002). Thus, while immune surveillance is crucial for the recognition and destruction of altered cells, chronically activated microglia (i.e., innate immune cells in the brain) can also induce apoptosis in neighboring, functioning cells and decrease the production of neuroprotective hormones (Blasko et al., 2004; Eikelenboom, Rozemuller, & van Muiswinkel, 1998; Liu & Hong, 2003). The resulting milieu provides favorable conditions for an active, chronic degenerative process; however, determining a causal rather than contributory role of inflammation in decline has proven to be a more difficult task.

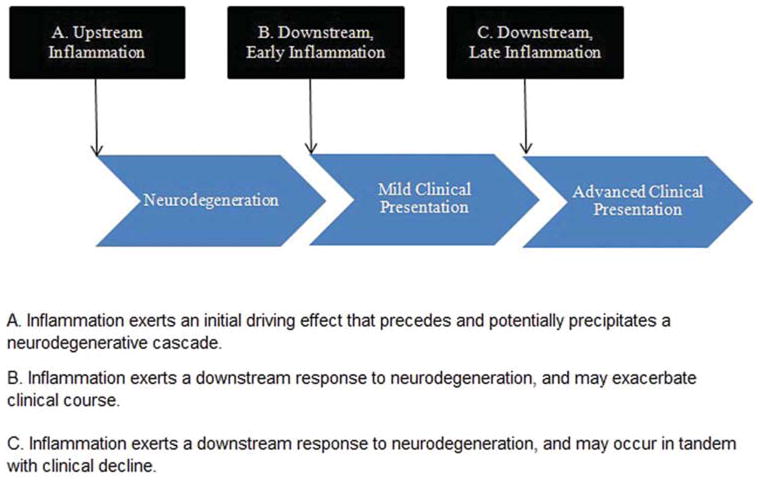

The point at which inflammatory processes come ‘on line’ alters the conceptualization of how inflammation might play a role in disease manifestation. As shown in Figure 1, if inflammation plays a precipitating role (A), then inflammatory markers should be elevated prior to imaging evidence of disease burden (e.g., amyloid) or neurodegeneration (i.e., atrophy). Importantly, this cannot definitively rule out a reactionary response to early degeneration, particularly given that the genesis of these diseases is hypothesized to extend 10–20 years prior to clinical manifestation (Dickerson et al., 2011); in addition, it does not rule out a contributory role for inflammation secondary to chronic, age-related diseases. However, an elevation in inflammatory markers directly preceding evidence of disease would nonetheless suggest an early pathogenic role in neurodegeneration. If instead, inflammation plays a contributory rather than precipitating role (B), then inflammatory markers should be elevated after neurodegeneration commences. Inflammatory markers may peak at early clinical stages (e.g., Mild Cognitive Impairment, MCI), and decline later as the immune system is overwhelmed. Finally, the impact of inflammation may also be primarily reactionary (C), with inflammatory markers increasing in concert with clinical severity, and thereby peaking at later stages of the disease course. In order to elucidate the stage at which anti-inflammatory medications might be most useful, if at all, in staving off cognitive decline, a more comprehensive understanding of the temporal mechanisms and relative tradeoffs (i.e., positive versus negative) of the inflammatory response is needed. Despite limited information regarding the temporal course and cognitive sequelae of inflammation, this model will be used in the current review to guide the interpretation of current clinical findings (Figure 1 here).

Figure 1.

Temporal course of inflammation in neurodegenerative disease, within the context of possible points of impact. Inflammation may play a precipitating (A), contributory (B), or reactionary (C) role in the disease process.

INFLAMMATION AND COGNITION

In addition to a mechanistic role in neurodegeneration, inflammation also exerts direct and indirect effects on cognition in older adults. During quiescent periods, inflammatory mediators play an important role in promoting cognitive functions, mainly in the domain of learning and memory (see Yirmiya & Goshen, 2011 for extensive review). Animal studies have demonstrated that cytokines like Interleukin-1 (IL-1) not only facilitate long-term potentiation (LTP), but also contribute to the maintenance of hippocampal neurogenesis (Ekdahl, Kokaia, & Lindvall, 2009; Vitkovic, Bockaert, & Jacque, 2000; Yirmiya & Goshen, 2011; Ziv et al., 2006). Further evidence supporting a central role of inflammatory cytokines in healthy cognitive functioning includes recent demonstration of an increase in IL-1 gene expression following induction of LTP, as well as thwarting of LTP in the face of altered IL-1 signaling (Yirmiya & Goshen, 2011).

Although immune mechanisms positively impact memory consolidation and neurogenesis under basal conditions (e.g., Il-1) and extend protective benefits for memory following brief, stressful conditions (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), sustained inflammatory responses have detrimental effects on a broad range of cognitive functions. More specifically, neuroinflammation has been implicated in impaired memory performance in older adults (Gunstad et al., 2006; Noble et al., 2010) and animal models (Semmler, Okulla, Sastre, Dumitrescu-Ozimek, & Heneka, 2005). In contrast with its role under physiological conditions, sustained neuroinflammation has been show to impair hippocampal functioning by disrupting long-term potentiation and memory formation (Lin et al., 2009; Murray & Lynch, 1998; Semmler et al., 2005; Terrando et al., 2010), suggesting that protracted and severe systemic inflammatory processes may serve as a contributing factor to memory dysfunction. Of particular relevance to clinical presentation in human neurodegenerative disease, recent animal studies have also utilized low-grade inflammatory models that more closely emulate the physiological conditions associated with aging and neurodegenerative disease. In a striking study involving heterochronic parabiosis in mice (i.e., conjoined older and younger mouse), age-dependent systemic elevations in chemokines were observed in both the older mice and the conjoined, parabiotic younger mice, which thwarted neurogenesis and impaired memory functions (Villeda et al., 2011). Additional studies using animal models of aging suggest that inflammation can directly affect the brain endothelium at low doses (Murray, Skelly, & Cunningham, 2011), and further support inflammation-mediated hippocampal dysfunction and memory consolidation deficits in older relative to young animals (Chen, Buchanan et al., 2008). Corroborating basic science work, recent studies indicate that non-demented, older adults with higher levels of systemic inflammatory markers perform worse on verbal memory tests at baseline (Noble et al., 2010; Teunissen et al., 2003) and evidence smaller hippocampi (Anan et al., 2011), left medial temporal lobes (Bettcher et al., in press), and total brain volume (Jefferson et al., 2007) than those with low or undetectable levels.

In addition to impoverished memory profiles, inflammatory markers have also been shown to negatively correlate with measures of executive functions and processing speed in functionally normal older adults (Marioni et al., 2009; Marsland et al., 2006). Recent evidence suggests that cytokine-mediated changes in vascular permeability, endothelial function, and microvascular structure (Sprague & Khalil, 2009) might contribute to dysexecutive patterns of neuropsychological performance. Specifically, higher levels of CRP have been linked with worse executive functions (Hoth et al., 2008) and lower global and frontal fractional anisotropy scores in community dwelling older adults, suggesting an indirect, vascular mechanism for cognitive dysfunction (Wersching et al., 2010).

In examining the time course, longitudinal studies of healthy older adults generally corroborate the observed negative relationship between inflammation and cognitive function (Dimopoulos et al., 2006; Komulainen et al., 2007; Marioni et al., 2009; Rafnsson et al., 2007; Weaver et al., 2002; Yaffe et al., 2003, 2004), although isolated studies suggest minimal to no relationship with cognitive decline (Alley, Crimmins, Karlamangla, Hu, & Seeman, 2008; Gimeno, Marmot, & Singh-Manoux, 2008). Factors such as ApoE4 status (Schram et al., 2007), metabolic syndrome (Yaffe et al., 2004), and degree of elevation in inflammatory markers (Dik et al., 2005) appear to influence the strength of this relationship; however, the specificity of cognitive domains affected and inflammatory mediators involved is unclear, as recent studies have yielded conflicting, and at times contradictory results (Alley et al., 2008; Dik et al., 2005; Hoth et al., 2008; Schram et al., 2007; Weuve, Ridker, Cook, Buring, & Grodstein, 2006). For example, in the Leiden 85-plus study, higher levels of IL-6 were related to decrements in both global cognition and memory function in older participants, with ApoE4 carriers evidencing the largest decline; in contrast, the Rotterdam Study suggested that higher levels of IL-6 were related to larger annual declines in global cognition in ApoE4 carriers only (Schram et al., 2007), with no association observed between inflammation and episodic memory decline. Over and above controversy surrounding the specificity of cognitive domains affected, other longitudinal studies suggest that the association between inflammation and neuropsychological tests may be largely accounted for by established predictors of cognition, namely age and general health status (Alley et al., 2008). The variability in findings highlight that while an association between inflammation and cognition is widely reported, the mechanisms of action and relative impact on decline remain poorly understood.

INFLAMMATION AND NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASE

To further parse the relative contribution of inflammation to cognitive decline, an appraisal of both the time course and clinical manifestation of the disease process is paramount. Recent attempts to capture early alterations in immune function have focused on older adults diagnosed with MCI, as these patients offer an early window into pathological changes that might contribute to disease progression (Bermejo et al., 2008; Buchhave et al., 2009). Of the few studies published, cross-sectional evaluations of MCI have rendered informative, but potentially concerning findings. Specifically, higher rates of IL-1β (Forlenza et al., 2009; Trollor et al., 2010), CRP (Roberts et al., 2009), and TNF-α(Bermejo et al., 2008; Trollor et al., 2010) have been observed in MCI relative to healthy controls, and more pronounced rates of inflammatory processes have been reported in early MCI (i.e., before plaques and tangles are reflected in CSF A42/tau profiles) compared to Alzheimer’s Disease patients (Schuitemaker et al., 2009). Differences or elevations in inflammatory markers are more frequently reported in MCI patients with non-amnestic or multiple-domain cognitive impairments (Forlenza et al., 2009; Trollor et al., 2010), although isolated studies have found no differences between patients and controls (Lindberg et al., 2005). Salient to the issue of temporal course is whether these patients are evidencing early stages of a neurodegenerative disease or a static process. A recent multi-method PET study by Okello et al. (2009) provides preliminary data linking inflammation to Alzheimer’s disease pathology, as they reported evidence of microglial activation and amyloid deposition in vivo in approximately half of patients with MCI. Collectively, studies on inflammation and MCI suggest that inflammatory mechanisms might render significant effects during early, ‘pre-clinical’ stages of the disease, and are more prominent in cognitive profiles typified by executive dysfunction or multiple impairments. While these studies provide accumulating evidence for a precipitating or contributory role of inflammation in neurodegenerative disease (see Figure 1A, B), it remains unclear whether the elevations in inflammatory markers at this stage represent a toxic or beneficial immune response to pathological changes in the brain.

Pursuant to this discussion, it is important to highlight that while MCI is purported to represent an early manifestation of a neurodegenerative disease, it remains a clinical diagnosis and hence may represent patently different underlying processes that are not necessarily degenerative over time. Thus, in order to clarify the relationship between inflammation, neurodegeneration, and cognition, the following sections will offer a focused review of inflammation in the context of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Frontotemporal dementia. The overarching aim of the following review is to synthesize recent research on the relationship between inflammation and clinical features of neurodegenerative diseases, including risk of development, cognitive and clinical correlates, and progression of the specified diseases. Emphasis will not be placed on isolating diagnostic differences (i.e., disease vs. control) in inflammatory markers, evaluating anti-inflammatory interventions, or delineating the molecular basis of inflammation (Blasko et al., 2004; Glass, Saijo, Winner, Marchetto, & Gage, 2010; Gorelick, 2010; McGeer & McGeer, 1995; Wyss-Coray & Mucke, 2002), but instead will be directed towards elucidating cognitive and neurobehavioral associations with inflammatory burden in neurodegenerative diseases. Inclusion criteria for the review were restricted to human studies published in the past 10 years with a primary cognitive or neurobehavioral outcome variable. Search terms included all diseases aforementioned and variations of the following keywords: inflammation, inflammatory, cytokines, TNF-α, IL-1, CRP, cognitive, mini-mental state examination (MMSE), memory, and executive function. Although studies incorporating a primarily genetic focus were included in the review, this paper does not provide a comprehensive analysis of inflammatory gene polymorphisms (Piehl & Olsson, 2009).

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease represents the most common form of dementia in the United States, and not surprisingly, is the most well researched in terms of how inflammation might impact neurodegeneration in older adults. Pathologically, Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by extracellular deposits of β-amyloid (senile plaques) and intracellular aggregates of phosphorylate tau protein (tangles), and is typified by relatively early neuropathological and atrophic changes in the medial temporal and temporoparietal regions, followed by progression to temporal and parietal neocortex and frontal lobes (Rabinovici et al., 2007).

The degree to which inflammation affects AD pathogenesis and progression remains controversial; however, there is growing consensus that inflammatory processes play at least a contributory role in AD pathology (McGeer & McGeer, 2001). Elevations in inflammatory cytokines and acute-phase proteins such as IL-1, IL-6, and CRP have been documented in Alzheimer’s patients (Bermejo et al., 2008; Grammas & Ovase, 2001; Kravitz, Corrada, & Kawas, 2009; Mancinella et al., 2009; Swardfager et al., 2010), and TNF-α elevations are reported to be as much as 25-fold higher in CSF relative to age-matched controls (Tarkowski, Blennow, Wallin, & Tarkowski, 1999). Interpretations of what these elevations means for AD pathology are often obscured by the mixed profile and roles of inflammatory mediators. At low levels, inflammatory mediators may buffer against A-β induced cytotoxicity and aid in the clearance of altered cells, suggesting that elevations may reflect a protective role in neurodegeneration (Barger et al., 1995). In addition, some cytokines possess robust anti-inflammatory properties that attempt to harness the immune response (e.g., IL-10; IL-11) in AD. Accumulating evidence suggests, however, that sustained elevations in cytokines may render an environment that is not only conducive for neurodegeneration, but also favorable for increased production of Aβ. At high levels, inflammatory mediators can stimulate the production and the synthesis of β amyloid precursor protein (Blasko et al., 2004; Grilli, Goffi, Memo, & Spano, 1996). In turn, Aβ can also induce the production of cytokines, particularly TNF-α(Galimberti, Fenoglio, & Scarpini, 2008).

Inflammation and later risk of developing AD

In considering the role of inflammation in AD clinical presentation, an understanding of how inflammatory mediators contribute to the longitudinal risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease is critical. An early, seminal report from the Honolulu-Asia Aging study indicated that men in the upper three quartiles of high-sensitivity serum CRP had a 3-fold increased risk for all dementias combined (including AD) when assessed 25 years later at follow-up (Schmidt et al., 2002). Associations between baseline peripheral levels of IL-6 and CRP (Engelhart et al., 2004), as well as baseline production of IL-1 and TNF-α(Tan et al., 2007) and future development of AD have been corroborated in other prospective cohort studies, suggesting that elevations in inflammatory mediators may be present years before clinical presentation of the disease. Further support for inflammation as a risk factor for future neurodegeneration also stems from a study that examined the likelihood of conversion from MCI to AD, noting that dysregulation in the TNF-α signaling pathway conferred greater risk for progressing to an AD dementia diagnosis (Diniz et al., 2010; Tarkowski, Andreasen, Tarkowski, & Blennow, 2003). Specifically, MCI patients who later progressed to AD had significantly higher serum soluble TNF receptor 1 levels (sTNFR1) compared to individuals who maintained an MCI diagnosis longitudinally (Diniz et al., 2010).

In contrast, other longitudinal studies have reported no association between inflammation and AD risk (Ravaglia et al., 2007; Sundelof et al., 2009). For example, a prospective 4-year follow-up study reported that inflammatory markers failed to predict AD development when considering other vascular risk factors, irrespective of whether inflammatory mediators were examined in isolation or in combination with other cytokines or acute-phase proteins (Ravaglia et al., 2007). Instead, they noted a robust independent relationship between hyperhomocysteinemia and AD risk, further highlighting not only the complex relationship between inflammatory markers and neurodegeneration, but also inflammation and vascular risk factors. Considering that mechanistically, sustained inflammation affects endothelial functioning and vascular permeability, this study begs the question of whether the frequently reported association between inflammation and AD risk is mediated or moderated by other vascular risk factors.

Cognitive correlates of inflammation in AD

In addition to the risk of developing a dementia, inflammation has also been show to associate with other important clinical aspects of AD, namely cognitive functioning. Consistent with the course of pathology progression, clinically, Alzheimer’s disease patients tend to present with early changes in episodic memory, followed by declines in visuospatial functioning, executive functions and language. Although the majority of efforts to characterize the relationship between inflammation and cognition have focused on cognitive decline in healthy elders or MCI, several studies suggest that elevations in inflammatory markers are related to both global cognitive impairment and verbal episodic memory declines in AD.

Specifically, elevations in acute phase proteins (i.e., alpha-1-antichymotrypsin; ACT), as well as cytokines (i.e., IL-1beta; IL-2; IL-18) have been shown to negatively correlate with global cognitive performance in AD patients (i.e., MMSE), suggesting that worse overall cognition is associated with higher levels of peripheral inflammatory markers (Bonotis et al., 2008; Bossu et al., 2008; Forlenza et al., 2009; Licastro et al., 2000; Tarkowski et al., 2003). Consistent with these findings, studies examining the functioning of immune cells also point to a negative correlation between the spontaneous release of cytokines (i.e., TNF-α) from natural killer cells and MMSE scores in AD (Solerte, Cravello, Ferrari, & Fioravanti, 2000). This further highlights that the function of immune cells, in addition to the levels of inflammatory mediators are related to global cognitive functioning in AD.

It is important to underscore, however, that additional cross-sectional studies report no significant correlations between inflammation and MMSE (Olgiati et al., 2010; Ozturk et al., 2007; Popp et al., 2009), positive correlations (Kim et al., 2008; Sala et al., 2003), or report associations only with specific cytokines (e.g., IL-1 levels, but not TNF-α) (Tarkowski et al., 2003). For example, Sala et al. (2003) reported a positive relationship between MMSE and three pro-inflammatory markers, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, and interpreted these findings as preliminary evidence for downregulation of inflammation in late clinical stages of the disease. While this muddies the interpretation of cognitive findings from a mechanistic standpoint (i.e., does inflammation simply respond to the degenerative process, or does it help drive it?), it also suggests that the association between inflammation and cognition may not be a robust linear relationship.

In addition, further information is needed regarding the relationship between inflammatory mediators and specific cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s disease. While isolated reports indicate a negative correlation between inflammatory mediators and episodic memory (Forlenza et al., 2009), there is a dearth of information regarding how inflammation might associate or interact with particular cognitive domains in AD. Recent studies have addressed other neurobehavioral correlates of inflammation, and reported significant associations between cytokine levels and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Olgiati et al., 2010; Ozturk et al., 2007); in particular, TNF-α levels have been shown to positively correlate with symptoms associated with sickness behavior (Holmes et al., 2011), including depression, anxiety, agitation, and apathy on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) in Alzheimer’s disease. However, there continues to be a lack of specificity in the literature regarding how and to what degree inflammation relates to specific cognitive and neurobehavioral processes.

Inflammation and clinical progression of AD

The potential association between inflammatory markers and clinical severity speaks to a larger issue regarding the role of inflammation in AD pathogenesis. The reported negative correlation between inflammation and cognitive functioning points to a possible reactionary role of inflammation in AD (see Figure 1C), as inflammatory markers may reach their peak later in the disease course. As noted, however, this relationship remains tenuous at best, suggesting that a more focused examination of inflammatory markers in the context of clinical trajectory is needed.

Both imaging and autopsies studies provide support for a relatively early role of inflammation in AD pathogenesis. Postmortem studies of patients with low Braak stages of AD pathology demonstrate colocalization of microglia and Abeta deposits (Arends, Duyckaerts, Rozemuller, Eikelenboom, & Hauw, 2000; Hoozemans et al., 2006; Vehmas, Kawas, Stewart, & Troncoso, 2003). Although imaging studies that address inflammation and AD are sparse, isolated reports corroborate these findings and further suggest that activation of microglia occurs prior to evidence of cerebral atrophy in AD patients (Cagnin et al., 2001).

Studies examining the relationship between inflammation and clinical stage (i.e., mild, moderate, severe) provide mixed results, although generally favor an early role for inflammation in AD. In support of an early role for inflammation in AD pathogenesis, several recent studies have reported lower levels of inflammatory markers in late or severe stages of AD compared to early or mild (Galimberti et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2008; Motta, Imbesi, Di Rosa, Stivala, & Malaguarnera, 2007; Sala et al., 2003). Motta et al. (2007) found that inflammatory cytokines (e.g., il-12, il-15, il-18) were higher in mild AD, ‘slightly lower’ in moderate AD, and comparable to non-demented age-matched controls in severe AD. Similarly, when analyzing a proxy analyte for inflammation (plasma fractalkine), Kim et al. (2008) reported significantly greater levels in patients with mild to moderate AD than in patients with severe AD, underscoring that inflammatory markers may reach their peak in early stages of the disease course, and subsequently decline as the immune system is overwhelmed. Furthermore, baseline levels of inflammatory markers (e.g., TNF-α) have also been shown to predict an increased rate of cognitive deterioration in AD, as indexed by the ADAS-COG score (Holmes et al., 2009). While older adults with high levels of TNF-α evidenced an accelerated decline over 6 months in this study, participants with low levels of TNF-α displayed minimal decline over the same time period (see later section on Comorbidity and Contributing Inflammatory Factors), suggesting that early elevations in inflammatory markers might exacerbate decline (Holmes et al., 2009).

Although the preliminary evidence on AD clinical stage and inflammatory markers points to an early role for inflammation in AD pathogenesis, isolated reports also suggest that it may play a reactionary role (Blasko et al., 2007; Scali et al., 2002). For example, when examining the progression of decline in AD, elevations in immune cell count were positively correlated with disease severity (i.e., higher basal CD11b levels in patients with more severe cognitive impairment) (Scali et al., 2002). In terms of AD progression and rate of change, contradictory findings are also evident, as evidenced by a relatively recent study suggesting that low levels of baseline CRP are associated with increased rapidity of decline in AD (Locascio et al., 2008).

Collectively, the evidence suggests that sustained inflammation detrimentally impacts cognitive functioning and may interact with neurodegeneration; however, whether inflammation is primarily culpable for these changes or precipitates cognitive decline in AD remains an unanswered question. More specifically, inconsistent findings render it difficult to interpret whether inflammatory mediators simply respond to increasing AD pathology (i.e., Figure 1C), even at an early stage, or if they play a pivotal role in the development and maintenance of disease (i.e., Figure 1A, B). Our understanding of how inflammation affects clinical presentation and neurodegeneration in AD is thus still in its infancy, with many unaddressed questions. For example, if inflammation accelerates decline in AD, what are the neurobiological processes by which this happens? Is the mechanism due to interruptions in long-term potentiation or even phagocytosis? Is it due to increased apoptosis or mediated by vascular mechanisms? Clearly, inflammation plays an integral role in Alzheimer’s disease course; however, the mechanism by which it interacts with neurodegeneration and affects clinical presentations remains unclear.

NSAID use and AD

Although the corpus of literature on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use is outside the scope of this review, the utility of NSAIDs in delaying cognitive decline is germane to the discussion of temporal course and role of inflammation in AD pathogenesis. While early epidemiological studies highlighted a reduced incidence of AD in NSAID users (McGeer, Rogers, & McGeer, 2006; in t’ Veld et al., 2001), results from clinical trials have been mixed, with many showing no effect of NSAID use on incident risk (Arvanitakis et al., 2008) or later development of AD (Lyketsos et al., 2007). One of the many critiques is that participants are often symptomatic prior to NSAID administration in these studies; thus, the application of NSAIDs may have been too late in the process to truly confer benefit. In support of an early, protective role of NSAID use in delaying AD, recent studies suggest that these medications may confer protection if given to asymptomatic participants several years prior to their first cognitive symptoms (Hayden et al., 2007).

Furthermore, the impact of NSAIDs on clinical presentation may differ based on the stage of disease progression. The ADAPT study (Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-Inflammatory Prevention Trial) has provided increased clarity on this complex topic by disentangling individual differences in disease progression and associating them with treatment response. By identifying 3 classes of participants (i.e., non-decliners, slow decliners, fast decliners), the ADAPT group recently demonstrated that NSAIDs may uniquely affect progression based on pre-clinical presentation. In particular, naproxen appeared to lessen cognitive decline in ‘slow decliners’, and accelerated decline in the ‘fast decliners’ (Breitner et al., 2011; Leoutsakos, Muthen, Breitner, & Lyketsos, 2011). Thus, while preliminary analyses suggested that NSAIDs might induce a net cognitive decline in older adults (Martin et al., 2008), secondary analyses of CSF biomarkers indicated reduced rates of ongoing AD pathogenesis in asymptomatic participants treated with naproxen, particularly after 2–3 years. The mechanistic role of COX-1 and COX-2 pathways in these findings remains unclear; however, ongoing examination of the ADAPT study has clearly drawn attention to the complex role of inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases, and highlighted that the impact of the inflammatory response (and the effectiveness of NSAIDs) may change over disease course. These findings also suggest that pre-clinical stages of disease progression may also be subdivided further into ‘critical’ stages in which NSAIDs might be maximally beneficial.

Parkinson’s disease

Although research studies have focused primarily on the role of inflammation in AD, a primary role for inflammation in Parkinson’s disease (PD) has garnered burgeoning attention in the past decade. Cardinal neuropathological features of PD include intracellular inclusions of α-synuclein (i.e., lewy bodies) and the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta of the midbrain. Although the pathological changes associated with PD involve prototypic degeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway, as the disease progresses, pathology is distributed more broadly and can be characterized as multisystemic in end stages.

Both human and animal models suggest that PD entails a significant inflammatory component (McGeer & McGeer, 2004), and indicate a selective vulnerability of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), basal ganglia and dopaminergic system to inflammatory insult. The SNpc ganglia are densely rich with microglia, rendering them potentially more susceptible to the effects of sustained inflammation in PD. Animal injected with inflammation-inducing agents (i.e., lipopolysaccaride) directly or proximally into the SNpc result in permanent depletion of nigral dopamine production (Herrera, Castano, Venero, Cano, & Machado, 2000), highlighting a causal link between inflammation and dopaminergic dysfunction. In toxic mouse models of PD (i.e., MPTP models), increases in SNpc cytokine levels, particularly TNF-α, are observed and have been shown to be highly toxic to dopaminergic neurons (Letiembre et al., 2009; McGeer & McGeer, 2008; Przedborski, 2010; Rogers, Mastroeni, Leonard, Joyce, & Grover, 2007). Furthermore, in corroboration of a central inflammatory mechanism in PD, prior administration of anti-inflammatory drugs (i.e., dexamethasone) results in less severe dopaminergic depletion in MPTP animal models (Kurkowska-Jastrzebska et al., 2004).

In human patients with PD, research findings regarding inflammatory mediators and NSAID use mirror those found in AD participants. Specifically, cytokine levels (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) are elevated in plasma and CSF relative to controls, and NSAID use is possibly associated with reduced risk of developing PD (Chen et al., 2003, 2005; McGeer & McGeer, 2004; Rentzos et al., 2009). In-vivo imaging and autopsy studies also confirm the presence of activated and reactive microglia, respectively, in the SNpc and striatum of PD patients (Block & Hong, 2007; Gerhard et al., 2006; McGeer & McGeer, 2008; Rogers et al., 2007); although these findings do not isolate a temporal course for inflammation and PD, they suggest an overlap between patholological changes and locus of inflammation.

Inflammation and risk of developing PD

Considering the relatively early age of onset, there is a dearth of research available on longitudinal risk for developing PD, particularly in regards to pre-clinical biomarkers of disease onset (Ravina et al., 2009; Wu, Le, & Jankovic, 2011). In the sole prospective study of inflammatory markers and PD, higher plasma levels of baseline IL-6 were associated with greater predictive risk of developing PD over a mean period of 4.3 years (Chen, O’Reilly, Schwarzschild, & Ascherio, 2008). Although this suggests that inflammation may potentially herald the onset of disease, no other inflammatory mediators (i.e., CRP, TNF-α) were associated with risk of developing PD in this study, thus the predictive role of inflammation in PD diagnosis remains unclear. Additional means of parsing out the predictive value of inflammatory markers in later PD diagnosis have included proxy examinations of NSAID use. Although numerous associations have been documented between NSAIDs and reduced PD risk (Gagne & Power, 2010; Gao, Chen, Schwarzschild, & Ascherio, 2011; McGeer & McGeer, 2007; Ton et al., 2006; Wahner, Bronstein, Bordelon, & Ritz, 2007), recent case-control studies suggest otherwise, with some even reporting an increased risk. (Hernan, Logroscino, & Garcia Rodriguez, 2006). For example, Driver, Logroscino, Lu, Gaziano, and Kurth (2011) reported no association between regular NSAID use and decreased PD risk, and highlighted that the heterogeneity in recent study findings may be partially attributable to confounding factors, such as medical comorbidities, duration of treatment, and indication bias (Becker, Jick, & Meier, 2011; Driver et al., 2011).

Neurobehavioral and cognitive correlates of inflammation

In recent cross-sectional evaluations of patients who have already received a diagnosis of PD, several attempts have been made to capture how inflammation might relate to functional and behavioral manifestations of the disease. Using proxy measures of disease staging and symptom severity (i.e., Hoehn and Yahr, H/Y; Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale, UPDRS), inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α; IL-6) and chemokines (i.e., RANTES) have been associated with functional disability (Menza et al., 2010; Reale et al., 2009; Rentzos et al., 2009; Scalzo, Kummer, Cardoso, & Teixeira, 2010), reduced gait speed (Scalzo et al., 2010), and depression (Hassin-Baer et al., 2011), although these relationships do not appear to be consistently linear. While this reiterates the possibility of a ‘threshold effect’, in which inflammatory mediators interact with clinical presentation at a specified level, additional studies are need to clarify these associations and further explicate the mechanisms by which they relate to neurobehavioral symptoms.

Although overt motor symptoms are emblematic of PD, non-demented patients also exhibit mild cognitive difficulties, particularly in the domains of spatial working memory, attention/concentration, and processing speed (Salmon & Filoteo, 2007). Despite the relative specificity in cognitive symptoms, most studies have focused on composite measures or indices of gross cognitive function (Hassin-Baer et al., 2011; Scalzo et al., 2010), yielding variable results (Dufek et al., 2009; Hassin-Baer et al., 2011; Menza et al., 2010; Scalzo et al., 2010). This is not particularly surprising given that the range of scores for gross cognitive measures (e.g., MMSE) is likely restricted in non-demented patients. Of the few studies to address specific cognitive measures, Hassin-Baer et al. (2011) reported no significant differences between individuals with high vs. low CRP levels and measures of attention, memory, and word fluency. In contrast, Menza et al. (2010) reported a negative association between TNF-α and a composite measure of cognition, as well as individual tests of naming (i.e., Boston naming) and inhibition (i.e., Stroop Color-Word test). Differences in cytokines, cognitive assessments, and covariates assessed in these studies make it difficult to interpret the conflicting findings, and suggest a potentially differential role for specific inflammatory analytes in clinical presentation.

Overall, the relative contribution of inflammation to cognitive and neurobehavioral symptoms continues to be an understudied area of clinical etiology in Parkinson’s disease. Although the literature points to a stronger association between inflammatory mediators and functional abilities in PD, the burgeoning work linking inflammation to specific cognitive symptoms is promising and remains uncharted.

Inflammation and clinical progression in PD

In examining the evidence for an inflammatory role in PD pathogenesis, converging evidence suggests that inflammation may play a pivotal position in early stages of disease onset and may in part drive progression; however, much of the support originates from animal studies, thus it is unclear how and to what degree inflammation might impact clinical progression in humans with PD. In a recent review paper, Rogers et al. (2007) clearly delineate several points of consideration, noting that many of the proposed environmental etiologies of PD (e.g., toxins, head trauma, viral exposure) engender activation of microglia, underscoring an inflammatory mechanism that precedes neurodegeneration (see Figure 1A). The authors further highlight that the substantia nigra contains the highest density of microglia in the brain, thereby offering a possible locus of inflammatory insult (Teunissen et al., 2003). While these observations intuitively point to an inflammatory mechanism in PD, the limited corpus of literature cannot definitively rule out a secondary, downstream role for inflammation in PD progression. Of the few studies conducted, evidence suggests that inflammatory mediators are elevated in early stages of PD relative to controls (Song, Chung, Kim, & Lee, 2011). In addition, a longitudinal, in vivo PET imaging study also reported increased uptake of a marker expressed by activated microglia in widespread regions of the brain (i.e., pons, basal ganglia, frontal, and temporal neocortices), corroborating an early role for inflammation in PD; however, no longitudinal change was noted in the 8 subjects they followed over the course of 2 years. The significance of static microglial activation in a small sample is unclear, as it does not speak to the level or function of the inflammatory mediators released, nor does it address the relationship between inflammation and long-term progression of the disease. It does serve to underscore, however, an early presence of inflammation in PD course. Future studies are needed to clarify not only the temporal course, but also the association between inflammatory mediators and rate of change in PD.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: bvFTD

A promising new area of research involves inflammatory cascades that may underlie or contribute to the development of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). FTLD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that results in selective early deterioration of frontal and temporal lobes. Considering the heterogeneity in clinical presentation of the disorder, the following section will cover the most well researched and common FTLD neurobehavioral syndrome, namely behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). The two most common pathologies associated with bvFTD are FTLD with tau-positive inclusions (FTLD-tau) and FTLD with TDP-43 positive inclusions (FTLD-TDP), and the atrophy distribution typically involves early alterations in bilateral frontal, anterior cingulate, anterior insula, and orbitofrontal regions, with later extension to the temporal lobes (Perry et al., 2006).

Although research on inflammatory markers and bvFTD is in its infancy, recent studies point to an increase in cytokine levels in patients compared to healthy controls (Galimberti et al., 2006; Galimberti, Schoonenboom et al., 2008; Rentzos, Zoga et al., 2006; Sheng, Zhu, Jones, Griffin, & Mrak, 2000; Sjogren, Folkesson, Blennow, & Tarkowski, 2004), and early microglial activation has been noted on in vivo PET imaging (Cagnin, Rossor, Sampson, Mackinnon, & Banati, 2004). Considering the absence of amyloid deposition on imaging (i.e., PIB) (Rabinovici et al., 2007), the mechanism by which inflammation affects neurodegeneration in bvFTD may stem from an early dysregulation of inflammatory mediators, particularly the TNF-α super family (Sjogren et al., 2004; Tang, Lu et al., 2011), rather than an induction of and/or response to misfolded protein aggregates. Germane to this hypothesis, Tang, Lu et al. (2011) recently reported that the growth factor, progranulin selectively binds to and inhibits TNF-α signaling in mice. Although altered progranulin levels have been documented in several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, this finding is particularly salient to bvFTD, as haplodeficiency in the gene coding for proganulin (PGRN) has been identified as one cause of the disease (Baker et al., 2006). The link between proganulin, TNF-α, and inflammation is promising, as it speaks to a potential mechanism by which inflammation might influence cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disease progression; however, whether a dysregulation in this system subserves or interacts with the neurodegenerative process and clinical presentation in bvFTD is unclear.

Cognitive correlates of inflammation in bvFTD

The clinical presentation of FTD is characterized by emotional blunting, reduced empathic concern, diminished insight, and profound changes in social comportment. Although bvFTD patients also evidence decrements in cognitive functioning, their neuropsychological profile is less pronounced than individuals with AD and not well captured by traditional cognitive batteries. Consistent with the topography of their brain atrophy, bvFTD patients often demonstrate relative sparing on simple visuospatial tasks, episodic memory, language, and global cognition, and may perform well on classic measures of executive functions during the early stages of their disease. As such, correlation analyses of inflammatory markers and gross cognitive measures (MMSE) in bvFTD have been non-significant (Galimberti, Schoonenboom et al., 2008; Rentzos, Paraskevas et al., 2006; Sjogren et al., 2004). Of note, evaluating the association between inflammation and cognition was not the expressed purpose of these studies, and individual studies included a heterogeneous mix of FTLD subtypes; however, these findings do underscore the lack of sensitivity of the MMSE in capturing both specific cognitive functions and overall dementia severity in bvFTD. In order to isolate the relation between inflammation and clinical features of bvFTD, it will be important for future studies to incorporate measures that specifically tap into deficits exhibited by bvFTD patients, namely indices of daily functioning, social comportment, and interpersonal behavior. Furthermore, no studies have examined the predictive value of baseline inflammatory markers in tracking future development of bvFTD or clinical progression of the disease.

Comorbidity and contributing inflammatory factors

Although increasing evidence points to a direct interplay between inflammation and neurodegeneration, it is also important to highlight that inflammation might indirectly impact clinical presentation via the cumulative effects of medical comorbidities and acute inflammatory events. Most age-related chronic conditions have an inflammatory component (Pawelec et al., 2002) that potentially ‘primes’ the older adult for exaggerated immune responses. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis, and smoking are comorbid medical conditions that have been shown to amplify an inflammatory response and contribute to cognitive decline (Rudin & Barzilai, 2005; Yaffe et al., 2004). Thus, inflammation may play an integral role in the clinical presentation of AD, PD, and FTD without specifically emanating from the neurodegenerative disease itself.

An older adult’s infection history and specifically, their exposure to systemic inflammatory events are critically important to consider when evaluating the association between inflammation and clinical presentation (Perry, Cunningham, & Holmes, 2007; Tang, Baranov et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2000). More importantly, when overlaid on a neurodegenerative disease, systemic inflammatory events may exacerbate clinical progression and accelerate cognitive decline. In several seminal studies on this topic, Holmes et al. (2003) evaluated the contribution of systemic infections to disease progression in AD patients. In an earlier work, they demonstrated that elevated serum IL-1 was associated with increased cognitive decline over the course of a 2-month period. More recently (Holmes et al., 2009), they demonstrated that not only were baseline TNF-α levels related to faster cognitive decline, but older adults with both elevated inflammatory markers and systemic inflammatory conditions demonstrated the greatest decline over 6 months. Although acute inflammatory events were primarily assessed in this study (e.g., respiratory infection), the authors also proposed that other chronic comorbidites, such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, and obesity may buttress this association between TNF-α and accelerated cognitive decline in dementia. Overall, their studies suggest that systemic inflammatory events may confer additional pathological risk in individual with preexisting neurodegenerative pathology.

Germane to the discussion of inflammatory ‘load’ and exacerbation of decline, considerable attention has been directed to the role of delirum in the clinical progression of neurodegenerative disease. Systemic infection, whether is caused by injury, infections, or surgical procedures, can spur episodes of delirium in older adults. Although anecdotal reports of frank, accelerated cognitive decline in older adults secondary to delirium are frequently discussed, objective evidence clearly suggests that episodes of delirium predict increased likelihood of dementia and institutionalization in older adults (Cunningham, 2011; Witlox et al., 2010). Animal studies have provided compelling support for the deleterious role of acute inflammatory symptoms and delirium in the clinical aggravation of neurodegenerative diseases. Namely, recent studies have demonstrated acute memory deficits (Murray et al., 2012) and extended transcription of CNS inflammatory mediators in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treated prion disease animals compared to LPS treated normal animals, in the face of comparable levels of circulating cytokines (Murray et al., 2011). These studies provide a proxy means of assessing the role of delirium when superimposed on a neurodegenerative disorder, and points to increased vulnerability for acute and prolonged cognitive perturbation in animals with pre-existing pathology (Cunningham et al., 2009). Human studies also underscore the clinical relevance of delirium in neurodegenerative disease progression. In a recent evaluation of patients with AD (Fong et al., 2009), the average decline in an overall measure of global cognitive functioning was 2.5 points per year (based on the Blessed IMC) prior to an episode of delirium. Individuals who experienced a delirium evidenced an increased rate of decline (4.9 points per post-delerium year) that was clinically equivalent to an 18-month decline compared to those who did not experience delirium.

Both animal and human studies highlight that the chronic inflammatory status of the individual, as well as acute inflammatory events, influence the clinical manifestation of neurodegenerative disease and can derail and ultimately accelerate the trajectory of cognitive decline. In order to garner a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms by which inflammation impacts the clinical course of neurodegeneration, more extensive, long-term studies are greatly needed (MacLullich & Hall, 2011).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Collectively, studies evaluating the role of inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases reveal a common thread, emphasizing that while inflammation plays a critical role in the disease course, more comprehensive, prospective evaluations are needed to identify the extent of its involvement. While Alzheimer’s disease has received disproportionate attention in this area of research, other neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Parkinson’s disease and Frontotemporal dementia, may offer promising models in which to evaluate protracted inflammatory processes in the context of age-related diseases. Part and parcel of this discussion is that inflammation is not necessarily a specific marker of individual neurodegenerative disorders, and may not confer risk for selective neuronal vulnerability in these clinically distinguishable disorders. Importantly, however, by assessing the role of immune dysfunction in multiple neurodegenerative diseases, disparate inflammatory narratives may appear. It may be that the ‘inflammation story’ is not the same for each neurodegenerative disease, and the relative ratio of immune benefit to toxicity might differ based on the temporal and functional role of inflammation in the neurodegenerative disease process.

Rather than focusing solely on diagnostic differences in inflammatory markers or debating whether inflammation is a feature of cognitive deterioration, future studies should prioritize efforts to parse the various mechanisms by which inflammation might impact decline and/or exacerbate neurodegeneration. Isolating the contributory role of comorbidities, acute systemic infection, and chronic inflammatory conditions is critical to our understanding of when inflammation comes ‘on line’ and how it impacts clinical presentation. In addition, although not the focus of the current review, genetic studies are crucial to our understanding of causality and mechanism of inflammation-mediated decline. Several studies have identified polymorphisms in inflammatory genes that affect clinical presentation in Alzheimer’s disease (Bossu et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2001; Parachikova et al., 2007; Perry, Collins, Wiener, Acton, & Go, 2001), Parkinson’s disease (Gardet et al., 2010), and Frontotemporal dementia (Rainero et al., 2009). Although likely not the sole mechanism of inflammatory insult, these studies underscore the importance of multi-method designs in understanding the complexity of immune mediated or modulated diseases.

While this review has pitched a deleterious role for inflammation in neurodegeneration, this is not necessarily to suggest that inflammation in the harbinger of disease nor is it to suggest that inflammation will assume the same role over the course of a disease. Clearly, the immune system is critical for maintaining homeostasis and warding off pathogens, and may exert beneficial effects at some time point in the neurodegenerative process. However, overwhelming evidence from animal studies and human research suggests that chronic, sustained elevations in inflammatory mediators likely yield negative consequences at both a cellular and clinical level. Are there methods of harnessing the beneficial profile of immune surveillance in neurodegenerative disease while quashing the adverse, self-propagating effects? Whether this is a tenable goal remains yet to be seen.

Finally, longitudinal studies using consistent inflammatory analytes are especially vital to elucidating the etiology, temporal features, and strength of the relationship between inflammation and cognitive functioning. Most importantly, information gleaned from future studies is crucial to solidifying how, when, and to what degree immune intervention efforts might mitigate cognitive deficits.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the research literature suggests that sustained inflammation detrimentally influences cognitive functioning and likely impacts neurodegeneration; however, whether inflammation is primarily culpable for these changes or precipitates neurodegeneration remains an unanswered question. Precipitating, exacerbating, and reactionary roles of inflammation in neurodegeneration are all possible explanations for the study findings, and are not mutually exclusive given the mixed profile of CNS inflammation. While studies on Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Frontotemporal dementia all point to an early role for inflammation in disease pathogenesis, our understanding of how inflammation affects disease inception and progression is still in its infancy.

References

- Alley DE, Crimmins EM, Karlamangla A, Hu P, Seeman TE. Inflammation and rate of cognitive change in high-functioning older adults. Journal of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2008;63:50–55. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anan F, Masaki T, Shimomura T, Fujiki M, Umeno Y, Eshima N, Saikawa T, Yoshimatsu H. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is associated with hippocampus volume in nondementia patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2011;60:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends YM, Duyckaerts C, Rozemuller JM, Eikelenboom P, Hauw JJ. Microglia, amyloid and dementia in alzheimer disease. A correlative study. Neurobiology of Aging. 2000;21:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z, Grodstein F, Bienias JL, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Kelly JF, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Relation of NSAIDs to incident AD, change in cognitive function, and AD pathology. Neurology. 2008;70:2219–2225. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313813.48505.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Sadovnick AD, Rollinson S, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–919. doi: 10.1038/nature05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger SW, Horster D, Furukawa K, Goodman Y, Krieglstein J, Mattson MP. Tumor necrosis factors alpha and beta protect neurons against amyloid beta-peptide toxicity: Evidence for involvement of a kappa B-binding factor and attenuation of peroxide and Ca2+ accumulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1995;92:9328–9332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Jick SS, Meier CR. NSAID use and risk of Parkinson disease: A population-based case-control study. European Journal of Neurology. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo P, Martin-Aragon S, Benedi J, Susin C, Felici E, Gil P, Ribera JM, Villar AM. Differences of peripheral inflammatory markers between mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Immunology Letters. 2008;117:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettcher BM, Wilheim R, Rigby T, Green R, Miller JM, Racine CA, Yaffe K, Miller BL, Kramer JH. C-Reactive protein is related to memory and medial temporal brain volume in older adults. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.240. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasko I, Knaus G, Weiss E, Kemmler G, Winkler C, Falkensammer G, Griesmacher A, Wurzner R, Marksteiner J, Fuchs D. Cognitive deterioration in Alzheimer’s disease is accompanied by increase of plasma neopterin. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41:694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasko I, Stampfer-Kountchev M, Robatscher P, Veerhuis R, Eikelenboom P, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. How chronic inflammation can affect the brain and support the development of Alzheimer’s disease in old age: The role of microglia and astrocytes. Aging Cell. 2004;3:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Hong JS. Chronic microglial activation and progressive dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2007;35:1127–1132. doi: 10.1042/BST0351127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonotis K, Krikki E, Holeva V, Aggouridaki C, Costa V, Baloyannis S. Systemic immune aberrations in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2008;193:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu P, Ciaramella A, Moro ML, Bellincampi L, Bernardini S, Federici G, Trequattrini A, Macciardi F, Spoletini I, Di Iulio F, et al. Interleukin 18 gene polymorphisms predict risk and outcome of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2007;78:807–811. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.103242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu P, Ciaramella A, Salani F, Bizzoni F, Varsi E, Di Iulio F, Giubilei F, Gianni W, Trequattrini A, Moro ML, et al. Interleukin-18 produced by peripheral blood cells is increased in Alzheimer’s disease and correlates with cognitive impairment. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity. 2008;22:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitner JC, Baker LD, Montine TJ, Meinert CL, Lyketsos CG, Ashe KH, Brandt J, Craft S, Evans DE, Green RC, et al. Extended results of the Alzheimer’s disease anti-inflammatory prevention trial. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2011;7:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchhave P, Janciauskiene S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Minthon L, Hansson O. Elevated plasma levels of soluble CD40 in incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience Letters. 2009;450:56–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Kennedy AM, Gunn RN, Myers R, Turkheimer FE, Jones T, Banati RB. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. Lancet. 2001;358:461–467. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnin A, Rossor M, Sampson EL, Mackinnon T, Banati RB. In vivo detection of microglial activation in frontotemporal dementia. Annals of Neurology. 2004;56:894–897. doi: 10.1002/ana.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Jacobs E, Schwarzschild MA, McCullough ML, Calle EE, Thun MJ, Ascherio A. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use and the risk for Parkinson’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 2005;58:963–967. doi: 10.1002/ana.20682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, O’Reilly EJ, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Peripheral inflammatory biomarkers and risk of Parkinson’s disease. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167:90–95. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang SM, Hernan MA, Schwarzschild MA, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Ascherio A. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60:1059–1064. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Buchanan JB, Sparkman NL, Godbout JP, Freund GG, Johnson RW. Neuroinflammation and disruption in working memory in aged mice after acute stimulation of the peripheral innate immune system. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity. 2008b;22:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C. Systemic inflammation and delirium: Important co-factors in the progression of dementia. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2011;39:945–953. doi: 10.1042/BST0390945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Campion S, Lunnon K, Murray CL, Woods JF, Deacon RM, Rawlins JN, Perry VH. Systemic inflammation induces acute behavioral and cognitive changes and accelerates neurodegenerative disease. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Stoub TR, Shah RC, Sperling RA, Killiany RJ, Albert MS, Hyman BT, Blacker D, Detoledo-Morrell L. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 2011;76:1395–1402. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dik MG, Jonker C, Hack CE, Smit JH, Comijs HC, Eikelenboom P. Serum inflammatory proteins and cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2005;64:1371–1377. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158281.08946.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos N, Piperi C, Salonicioti A, Mitropoulos P, Kallai E, Liappas I, Lea RW, Kalofoutis A. Indices of low-grade chronic inflammation correlate with early cognitive deterioration in an elderly Greek population. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;398:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Ojopi EB, Talib LL, Mendonca VA, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV. Higher serum sTNFR1 level predicts conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;22:1305–1311. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver JA, Logroscino G, Lu L, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Parkinson’s disease: Nested case-control study. British Medical Journal. 2011;342:d198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufek M, Hamanova M, Lokaj J, Goldemund D, Rektorova I, Michalkova Z, Sheardova K, Rektor I. Serum inflammatory biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2009;15:318–320. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelenboom P, Rozemuller JM, van Muiswinkel FL. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease: Relationships between pathogenic mechanisms and clinical expression. Experimental Neurology. 1998;154:89–98. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl CT, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Brain inflammation and adult neurogenesis: The dual role of microglia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Meijer J, Kiliaan A, Ruitenberg A, van Swieten JC, Stijnen T, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM. Inflammatory proteins in plasma and the risk of dementia: The rotterdam study. Archives of Neurology. 2004;61:668–672. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong TG, Jones RN, Shi P, Marcantonio ER, Yap L, Rudolph JL, Yang FM, Kiely DK, Inouye SK. Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72:1570–1575. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a4129a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlenza OV, Diniz BS, Talib LL, Mendonca VA, Ojopi EB, Gattaz WF, Teixeira AL. Increased serum IL-1beta level in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2009;28:507–512. doi: 10.1159/000255051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JJ, Power MC. Anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Parkinson disease: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 2010;74:995–1002. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d5a4a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti D, Fenoglio C, Scarpini E. Inflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: Friend or foe? Current Aging Science. 2008;1:30–41. doi: 10.2174/1874609810801010030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti D, Schoonenboom N, Scheltens P, Fenoglio C, Venturelli E, Pijnenburg YA, Bresolin N, Scarpini E. Intrathecal chemokine levels in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2006;66:146–147. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191324.08289.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti D, Venturelli E, Fenoglio C, Guidi I, Villa C, Bergamaschini L, Cortini F, Scalabrini D, Baron P, Vergani C, Bresolin N, Scarpini E. Intrathecal levels of IL-6, IL-11 and LIF in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Journal of Neurology. 2008;255:539–544. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0737-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Chen H, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Use of ibuprofen and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2011;76:863–869. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820f2d79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardet A, Benita Y, Li C, Sands BE, Ballester I, Stevens C, Korzenik JR, Rioux JD, Daly MJ, Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. LRRK2 is involved in the IFN-gamma response and host response to pathogens. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185:5577–5585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard A, Pavese N, Hotton G, Turkheimer F, Es M, Hammers A, Eggert K, Oertel W, Banati RB, Brooks DJ. In vivo imaging of microglial activation with [11C](R)-PK11195 PET in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2006;21:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno D, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A. Inflammatory markers and cognitive function in middle-aged adults: The Whitehall II study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:1322–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunta S. Exploring the complex relations between inflammation and aging (inflamm-aging): Anti-inflamm-aging remodelling of inflamm-aging, from robustness to frailty. Inflammation Research. 2008;57:558–563. doi: 10.1007/s00011-008-7243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick PB. Role of inflammation in cognitive impairment: Results of observational epidemiological studies and clinical trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1207:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammas P, Ovase R. Inflammatory factors are elevated in brain microvessels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2001;22:837–842. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli M, Goffi F, Memo M, Spano P. Interleukin-1beta and glutamate activate the NF-kappaB/Rel binding site from the regulatory region of the amyloid precursor protein gene in primary neuronal cultures. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:15002–15007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunstad J, Bausserman L, Paul RH, Tate DF, Hoth K, Poppas A, Jefferson AL, Cohen RA. C-reactive protein, but not homocysteine, is related to cognitive dysfunction in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;13:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassin-Baer S, Cohen OS, Vakil E, Molshazki N, Sela BA, Nitsan Z, Chapman J, Tanne D. Is C-reactive protein level a marker of advanced motor and neuropsychiatric complications in Parkinson’s disease? Journal of Neural Transmission. 2011;118:539–543. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0535-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden KM, Zandi PP, Khachaturian AS, Szekely CA, Fotuhi M, Norton MC, Tschanz JT, Pieper CF, Corcoran C, Lyketsos CG, et al. Does NSAID use modify cognitive trajectories in the elderly? The Cache County study. Neurology. 2007;69:275–282. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265223.25679.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernan MA, Logroscino G, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the incidence of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;66:1097–1099. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000204446.82823.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera AJ, Castano A, Venero JL, Cano J, Machado A. The single intranigral injection of LPS as a new model for studying the selective effects of inflammatory reactions on dopaminergic system. Neurobiology of Disease. 2000;7:429–447. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Cunningham C, Zotova E, Culliford D, Perry VH. Proinflammatory cytokines, sickness behavior, and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:212–218. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ae07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Cunningham C, Zotova E, Woolford J, Dean C, Kerr S, Culliford D, Perry VH. Systemic inflammation and disease progression in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:768–774. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b6bb95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, El-Okl M, Williams AL, Cunningham C, Wilcockson D, Perry VH. Systemic infection, interleukin 1beta, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2003;74:788–789. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.6.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Rozemuller JM, Eikelenboom P. Neuroinflammation and regeneration in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2006;24:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth KF, Haley AP, Gunstad J, Paul RH, Poppas A, Jefferson AL, Tate DF, Ono M, Jerskey BA, Cohen RA. Elevated C-reactive protein is related to cognitive decline in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2008;56:1898–1903. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01930.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- in t’ Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, Launer LJ, van Duijn CM, Stijnen T, Breteler MM, Stricker BH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1515–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Wolf PA, Seshadri S, Au R, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Keaney JF, Jr, Lipinska I, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with total brain volume: The Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2007;68:1032–1038. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257815.20548.df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TS, Lim HK, Lee JY, Kim DJ, Park S, Lee C, Lee CU. Changes in the levels of plasma soluble fractalkine in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;436:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komulainen P, Lakka TA, Kivipelto M, Hassinen M, Penttila IM, Helkala EL, Gylling H, Nissinen A, Rauramaa R. Serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein and cognitive function in elderly women. Age and Ageing. 2007;36:443–448. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz BA, Corrada MM, Kawas CH. Elevated C-reactive protein levels are associated with prevalent dementia in the oldest-old. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2009;5:318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.04.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I, Litwin T, Joniec I, Ciesielska A, Przybylkowski A, Czlonkowski A, Czlonkowska A. Dexamethasone protects against dopaminergic neurons damage in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. International Immunopharmacology. 2004;4:1307–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoutsakos JM, Muthen BO, Breitner JC, Lyketsos CG. Effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatments on cognitive decline vary by phase of pre-clinical Alzheimer disease: Findings from the randomized controlled Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1002/gps.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letiembre M, Liu Y, Walter S, Hao W, Pfander T, Wrede A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Fassbender K. Screening of innate immune receptors in neurodegenerative diseases: A similar pattern. Neurobiology of Aging. 2009;30:759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licastro F, Pedrini S, Caputo L, Annoni G, Davis LJ, Ferri C, Casadei V, Grimaldi LM. Increased plasma levels of interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Peripheral inflammation or signals from the brain? Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2000;103:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HB, Yang XM, Li TJ, Cheng YF, Zhang HT, Xu JP. Memory deficits and neurochemical changes induced by C-reactive protein in rats: Implication in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2009;204:705–714. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1499-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg C, Chromek M, Ahrengart L, Brauner A, Schultzberg M, Garlind A. Soluble interleukin-1 receptor type II, IL-18 and caspase-1 in mild cognitive impairment and severe Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochemistry International. 2005;46:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Hong JS. Role of microglia in inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanisms and strategies for therapeutic intervention. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;304:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locascio JJ, Fukumoto H, Yap L, Bottiglieri T, Growdon JH, Hyman BT, Irizarry MC. Plasma amyloid beta-protein and C-reactive protein in relation to the rate of progression of Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology. 2008;65:776–785. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.6.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, Green RC, Martin BK, Meinert C, Piantadosi S, Sabbagh M. Naproxen and celecoxib do not prevent AD in early results from a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:1800–1808. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260269.93245.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLullich AM, Hall RJ. Who understands delirium? Age and Ageing. 2011;40:412–414. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancinella A, Mancinella M, Carpinteri G, Bellomo A, Fossati C, Gianturco V, Iori A, Ettorre E, Troisi G, Marigliano V. Is there a relationship between high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and dementia? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2009;49(Suppl 1):185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni RE, Stewart MC, Murray GD, Deary IJ, Fowkes FG, Lowe GD, Rumley A, Price JF. Peripheral levels of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, and plasma viscosity predict future cognitive decline in individuals without dementia. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:901–906. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b1e538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland AL, Petersen KL, Sathanoori R, Muldoon MF, Neumann SA, Ryan C, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Interleukin-6 covaries inversely with cognitive performance among middle-aged community volunteers. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:895–903. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238451.22174.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BK, Szekely C, Brandt J, Piantadosi S, Breitner JC, Craft S, Evans D, Green R, Mullan M. Cognitive function over time in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT): Results of a randomized, controlled trial of naproxen and celecoxib. Archives of Neurology. 2008;65:896–905. doi: 10.1001/archneur.2008.65.7.nct70006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]