Abstract

Ovarian hormone decline after menopause may influence cognitive performance and increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in women. Amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) has been proposed to be the primary cause of AD. In this study, we examined whether ovariectomy (OVX) could affect the levels of cofactors Aβ-binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE), which have been reported to potentiate Aβ-mediated neuronal perturbation, in mouse hippocampus, correlating with estrogen and Aβ levels. Female ICR mice were randomly divided into ovariectomized or sham-operated groups, and biochemical analyses were carried out at 5 weeks after the operation. OVX for 5 weeks significantly decreased hippocampal 17β-estradiol level, while it tended to reduce the hormone level in serum, compared with the sham-operated control. In contrast, OVX did not affect hippocampal Aβ1-40 level, although it significantly increased serum Aβ1-40 level. Furthermore, we demonstrated that OVX increased hippocampal ABAD level in neurons, but not astrocytes, while it did not affect RAGE level. These findings suggest that the expression of neuronal ABAD depends on estrogen level in the hippocampus and the increase in serum Aβ and hippocampal ABAD induced by ovarian hormone decline may be associated with pre-stage of memory deficit in postmenopausal women and Aβ-mediated AD pathology.

Keywords: Ovariectomy, Alzheimer’s disease, β-Amyloid, ABAD

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia among the aging population worldwide. The well-known risk factors for AD are increasing age, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, stroke and ApoE 4 polymorphism. Moreover, clinical studies have shown that ovarian hormone deprivation after menopause can increase AD prevalence (Tang et al., 1996), and that the prevalence and incidence of AD are higher in postmenopausal women than in age-matched men (Gao et al., 1998).

The deposition of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) is a hallmark of AD pathology, and cytotoxic Aβ production plays an essential and pivotal role in neuronal degeneration (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Tanzi and Bertram, 2005). In vitro findings from cultured neurons suggest that estrogen may prevent AD pathogenesis by reducing Aβ generation, protecting against Aβ-mediated neurotoxicity, and enhancing Aβ clearance (Xu et al., 2006; Li et al., 2000). In addition, recent studies indicate that estrogen protects against Aβ-induced neuronal death by maintaining mitochondrial function (Yao et al., 2007; Nilsen et al., 2006). These finding indicate that Aβ and estrogen relate closely and incompatibly regulate Aβ-mediated AD pathology.

Meanwhile, there is much evidence showing that a lower amount of Aβ oligomers can perturb synaptic dysfunction (Lacor et al., 2007; Haass and Selkoe, 2007), which may be implicated in pathogenesis in an early stage of AD. These findings also suggest the presence of cofactors potentiating Aβ neurotoxicity. Indeed, Yan et al. identified Aβ-binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) (the same molecule as endoplasmic reticulum-associated Aβ-binding protein or short chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase) (Yan et al., 1997) and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) (Yan et al., 1996) as such cofactors, which can bind Aβ in the nanomolar range and amplify Aβ-induced neuronal stress. In addition, these studies have demonstrated that the protein levels of ABAD and RAGE are increased in AD brains (Yan et al., 1996, 1997). Furthermore, ABAD is shown to enrich in mitochondria of neurons, has enzymatic activity toward a broad array of substrates, linear alcohols and steroid substrates, S-acetoacetyl-CoA and β-hydroxybutyrate (Yan and Stern, 2005), and catalyzes the oxidation of 17β-estradiol, a potent estrogen, and weaken its protective effects (He et al., 1999). On the other hand, RAGE, known as a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell surface molecules, is expressed in a variety of cell types including neurons (Brett et al., 1993) and interacts with a broad repertoire of ligands in addition to its first recognized ligands, advanced glycation end products (Bierhaus et al., 2005). The interaction of RAGE with its ligands generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) followed by activation of proinflammatory transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB, which may contribute to the acceleration and development of aging and chronic neurodegenerative disorders by stimulating the expression of numerous target genes including RAGE itself (Mukhopadhyay and Mukherjee, 2005). Recent study further indicated that estrogen decreased brain mitochondrial ROS production (Razmara et al., 2007). However, it is entirely unknown whether estrogens decline after menopause influences the expression of ABAD and RAGE.

In the present study, we examined the effects of ovariectomy (OVX) on protein levels of ABAD and RAGE in the mouse hippocampus correlating with estrogen and Aβ levels, to elucidate the association between postmenopausal ovarian hormone decline and Aβ-mediated AD pathology.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and treatment

Female ICR mice (Japan SLC Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan) were obtained at 8–9 weeks old and used for the experiments. They were housed under a standard light/dark cycle (12-h light starting at 8:45 h) at a constant temperature of 23 ± 1 °C. The animals had free access to food and water and were handled in accordance with the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kanazawa University, the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals approved by the Japanese Pharmacological Society, and the United States National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

One week after arrival, all experimental animals were bilaterally ovariectomized or sham-operated under pentobarbital (40 mg/kg) anesthesia. We have recently found that combination of OVX and restraint stress for totally 5 weeks causes an increase β-secretase activity in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions, and OVX alone for 5 weeks shows similar effect in dentate gyrus (DG) (Fukuzaki et al., 2008). Thus, in this study, biochemical analyses were performed 5 weeks after the operation.

2.2. Sample preparation for measurement of 17β-estradiol and Aβ levels

Animals were sacrificed by rapid decapitation and trunk blood was collected, permitted to clot for 30 min at room temperature, and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min. The resulting serum fraction of each sample was stored at −80 °C until assay. The brains were immediately removed, and the hippocampi were dissected away and lysed in with standard diluent and disrupted with a handheld homogenizer. The homogenates were centrifuged at 800 × g at 4 °C for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant was stored at −80 °C until assay. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

2.3. Quantification of 17β-estradiol level

The 17β-estradiol level was determined using the estradiol EIA kit (Cayman chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The diluted sample, standards, AChE tracer and rabbit anti-estradiol were put into the appropriate wells of microtiter plates coated with mouse anti-rabbit IgG. After incubation for 60 min at room temperature, all wells were washed five times and developed with Ellman’s reagent for 60 min. Absorbance at 405 nm was determined using the Bio-Rad Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Data are expressed as pg of 17β-estradiol per ml (serum) or mg protein (hippocampus).

2.4. Quantification of Aβ level

The Aβ level was determined using the Human/Rat β amyloid (40) ELISA Kit Wako (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The diluted serum and standards were put into the appropriate wells of microtiter plates coated with anti-human Aβ11-18 monoclonal antibody (clone BNT77). After incubation overnight at 4 °C, all wells were washed five times and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-Aβ1-40 monoclonal antibody (clone BA27) for 60 min at 4 °C. All wells were further washed five times and reacted with TMB solution. Absorbance at 450 nm was determined using the Bio-Rad Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Data are expressed as a percentage of the control. Data are expressed as fmol of Aβ1-40/ml (serum) or mg protein (hippocampus).

2.5. Immunoblot analyses of ABAD and RAGE

Animals were sacrificed by rapid decapitation and the brains were quickly removed and coronally sliced at 1 mm thick using a Brain Matrix (BrainScience Idea, Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Tissue blocks of the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions, and dentate gyrus were isolated from coronal sections on ice under a microscope with 10-fold magnification, homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 250 mM sucrose, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin A) and disrupted with 20 strokes of a Daunce homogenizer. Nuclei and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were further separated into cytosol and membrane fractions by centrifugation at 20,400 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The supernatants (cytosolic fractions) were transferred to new tubes and the pellets (membrane fractions) were resuspended in 15 μl of lysis buffer. The protein content of each fraction was determined using a Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay.

For immunodetection of ABAD, cytosolic fractions containing equal amounts of protein (20 μg: CA1, DG; 10 μg: CA3) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (reduced 10%). The separated proteins were transferred electrophoretically to a hydrophobic polyvinylidene diflouride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore Co., Billerica, MA). The blotted membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% non-fat skim milk/TBS-T (20 mM Tris–HCl and 137 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.6), and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary polyclonal antibodies raised against mouse anti-ERAB (ABAD) IgG1 (clone 23, 1:1000; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in 5% skim milk/TBS-T. Membranes were then washed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:2000; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). The immune complexes were visualized using Amersham ECL Plus™ Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare BioSciences, Piscataway, NJ). The blots were incubated for 15 min at 55 °C in stripping buffer (PBS including 0.2% mercaptoethanol) and washed four times with TBS-T, followed by saturation in 5% skim milk/TBS-T for 1 h at room temperature. To quantify the relative amount of proteins, the blots were incubated with the primary antibody detecting GAPDH (clone 6C5, 1:2000; EMD Chemicals, Inc., San Diego, CA) in 5% skim milk/TBS-T overnight at 4 °C, and then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody as described above. The result was processed using Amersham ECL™ Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare BioSciences). Quantification was performed using a light-capture cooled CCD camera system for bio/chemiluminescence detection (AE-6972FC; Atto Co., Tokyo, Japan).

For immunodetection of RAGE, membrane fractions containing equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (reduced 10%) and transferred electrophoretically to a PVDF membrane. RAGE proteins were detected using rabbit anti-RAGE IgG (1:1000; Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; KPL) and Amersham ECL™ Western Blotting Detection Reagents. The relative amount of proteins were quantified by reprobing with mouse anti-β-actin IgG1 (clone AC-15, 1:5000, Sigma–Aldrich Co.)

2.6. Immnohistochemistry of ABAD, NeuN and GFAP

Immunohistochemistry was carried out according to standard procedures (Caspersen et al., 2005). Animals were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused intracardially with 4% PFA in PBS. The brains were removed, post-fixed with the same fixative and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose-containing PBS. Sections (20 μm) containing hippocampus were obtained using a rotary microtome (HM505E; MICROM International GmbH, Walldorf, Germany), mounted on slides, and stored at −80 °C until use. The sections were fixed with 4% PFA, washed with 0.4% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PBS and incubated with a mixture of 10% donkey serum and 1% BSA in 0.1 M PBS to block a nonspecific binding by antibodies. The sections were then incubated with mouse anti-NeuN IgG (clone A60, 1:200; Millipore Co.) mouse, anti-GFAP IgG (clone G-A-5, 1:1500; Sigma–Aldrich Co.) and rabbit anti-ABAD IgG (1:75) (Yan et al., 2000) overnight at room temperature, and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor®546 anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-rabbit IgG (1:100; Invitrogen Co.) for 1.5 h. After the reaction, the sections were washed five times with 0.1 M PBS, mounted on coated slides, dehydrated, and cover-slipped.

Photomicrographs were taken using a microscope digital camera system (AxioCam/Axio Imager; Carl Zeiss) at 5× magnification and a confocal-laser scanning microscope (LSM 510) at 40× magnification. To prevent variability in staining due to each experimental procedure, the brains of four mice, equated across experimental groups, were processed at the same slide using the same reagents and temperature conditions.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The experimental data were statistically analyzed using StatView 5.0 Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The significance of differences was determined by the unpaired t-test. The criterion for statistical significance was p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of OVX on 17β-estradiol and Aβ levels in serum and hippocampus

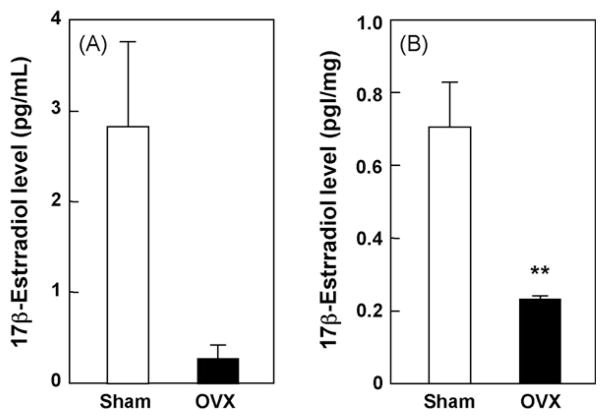

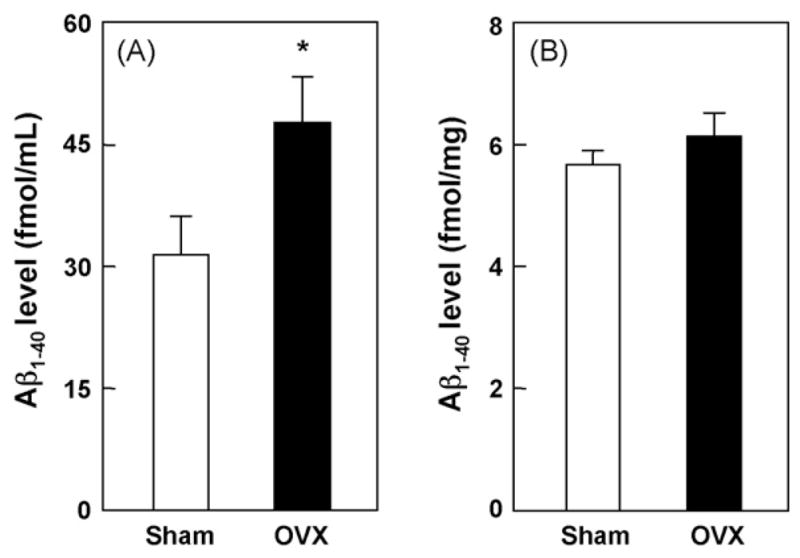

We first examined the effects of OVX on 17β-estradiol level in serum and hippocampus. OVX tended to reduce the 17β-estradiol level in serum (Fig. 1A) (p = 0.607), and significantly decreased the 17β-estradiol level in the hippocampus (Fig. 1B) (p < 0.05), compared with sham-operated control group including all estrous cycle mice. We also examined the effects of OVX on Aβ level in serum and hippocampus. As it is generally known that the ratio of generation for two major isoforms of Aβ, 1–40 and 1–42 fragments is 5:1 (Basun et al., 2002), we measured Aβ1-40 levels by ELISA in this study, which showed that OVX for 5 weeks significantly increased serum Aβ1-40 level in mice, compared with the sham-operated control (Fig. 2A) (p < 0.05). However, OVX for 5 weeks did not affect hippocampal Aβ1-40 level (Fig. 2B) (p = 0.3238).

Fig. 1.

Effect of OVX on 17β-estradiol levels in serum and hippocampus. Samples were prepared 5 weeks after OVX and 17β-estradiol levels were determined by EIA. Values indicate the mean ± S.E. (sham: n = 4; OVX: n = 4). **p < 0.01, compared with the sham-operated control group (unpaired t-test).

Fig. 2.

Effect of OVX on Aβ levels in serum and hippocampus. Samples were prepared 5 weeks after OVX and Aβ1-40 levels were determined by ELISA. Values indicate the mean ± S.E. (sham: n = 5; OVX: n = 5). *p < 0.05, compared with the sham-operated control group (unpaired t-test).

3.2. Effects of OVX on expressions of ABAD and RAGE in the hippocampus

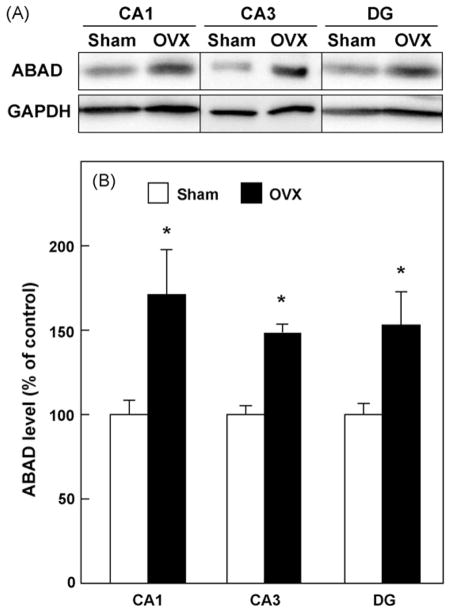

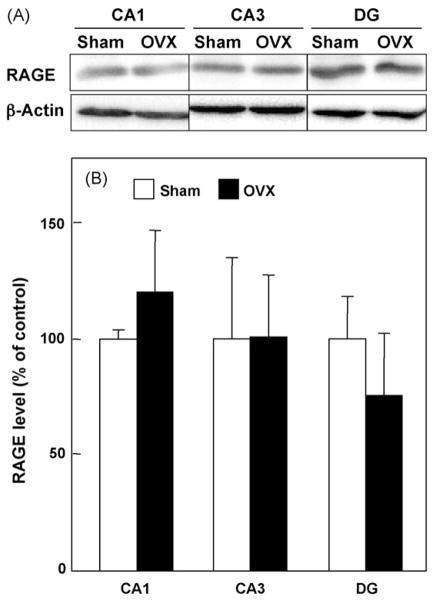

Next, we examined the effects of OVX on the expression of ABAD and RAGE in hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions and DG by immunoblot analyses. As shown in Fig. 3, OVX for 5 weeks increased the protein levels of ABAD in CA1, CA3 and DG regions of the hippocampus, compared with the sham-operated control (p < 0.05). In contrast, OVX for 5 weeks did not influence the protein levels of RAGE in CA1 (p = 0.2717), CA3 (p = 0.9909) and DG regions (p = 0.4420) of the hippocampus (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Effect of OVX on ABAD protein levels in hippocampal CA1, CA3 regions and dentate gyrus (DG). The indicated tissue homogenates were prepared 5 weeks after OVX and subjected to SDS-PAGE. (A) Typical immunoblot images detected by antibodies against ABAD (upper) and GAPDH (lower) are shown from four independent experiments. (B) ABAD levels, which were normalized by GAPDH levels, were expressed as % of the sham-operated control. Values indicate the mean ± S.E. (sham: n = 4; OVX: n = 4). *p < 0.05, compared with the sham-operated control group.

Fig. 4.

Effect of OVX on RAGE protein levels in hippocampal CA1, CA3 regions and dentate gyrus (DG). (A) Typical immunoblot images detected by antibodies against RAGE (upper) and β-actin (lower) are shown from four independent experiments. (B) RAGE levels, which were normalized by β-actin levels, were expressed as % of the sham-operated control. Values indicate the mean ± S.E. (sham: n = 4; OVX: n = 4).

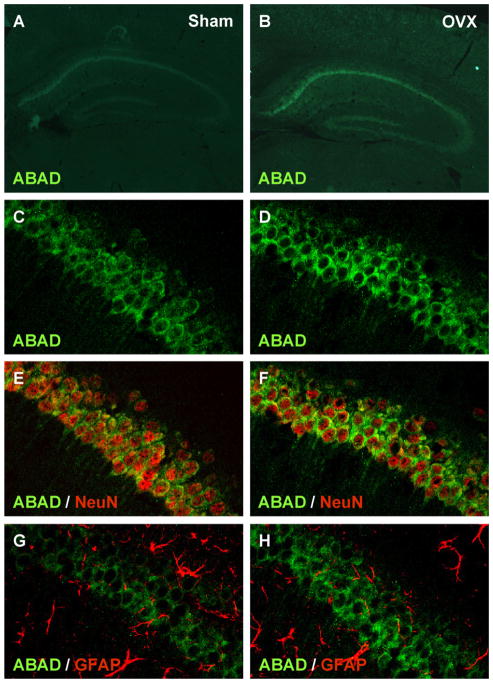

3.3. OVX induces hippocampal ABAD expression in neurons but not astrocytes

To determine the cell type, in which the expression of ABAD was induced by OVX in the hippocampus, we finally carried out immunohistochemical studies using anti-NeuN and anti-GFAP, which detect a neural nuclei protein and an astrocyte structural protein, respectively. Low-magnified immunofluorescent images of brain sections from OVX mice displayed that the enhanced fluorescent signal indicating the ABAD was observed in the both pyramidal and granule cell layers of hippocampus, especially the pyramidal cell layer in the CA1 region (Fig. 5B), compared with the sham-operated control (Fig. 5A). In addition, high-magnified confocal immunofluorescent images demonstrated that ABAD in the pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampal CA1 region was expressed in NeuN-positive cells (Fig. 5E), but not GFAP-positive cells (Fig. 5G). We also showed that OVX increased the neuronal ABAD in the hippocampal region (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, we observed similar ABAD expression in NeuN-positive cells, but not GFAP-positive cells, in the pyramidal cell layer of the CA3 region (Supplementary Fig. 1) and the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

OVX mice show an outstanding localization of ABAD in the hippocampal pyramidal neurons. (A and B) Typical low-magnified immunofluorescent images stained by anti-ABAD/Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-IgG (green) of brain sections including whole hippocampal CA regions from OVX (B) and sham-operated control group (A). (C–H) Typical high-magnified confocal immunofluorescent images stained by anti-ABAD/Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-IgG (green) (C–H), anti-NeuN/Alexa Fluor® 546 anti-IgG (red) (E and F) and anti-GFAP/Alexa Fluor® 546 anti-IgG (red) (G and H) of hippocampal CA1 regions from OVX (D, F and H) and sham-operated control group (C, E and G).

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined whether ovarian hormone depletion influences the Aβ and 17β-estradiol levels in both serum and hippocampus, and then the protein levels of ABAD and RAGE, which were reported as cofactors stimulating Aβ neurotoxicity and might contribute to the pathogenesis in early AD, in mouse hippocampus. As a result, we found that OVX increased the serum Aβ1-40 level, while it tended to reduce the serum 17β-estradiol level. In contrast, OVX significantly decreased the hippocampal 17β-estradiol level, although it did not affect hippocampal Aβ1-40 level. We further demonstrated that OVX increased hippocampal ABAD level in neurons, but not in astrocytes, while it did not affect RAGE level. These results suggest that ovarian hormone decline after menopause is involved in both the initiation and progression of AD by increasing serum Aβ and neuronal ABAD levels, and that the expression of neuronal ABAD depends on estrogen level in the hippocampus.

In addition to the direct protective effects against Aβ neurotoxicity (Cordey et al., 2003), estrogen has been shown to ameliorate AD-related neurodegeneration by regulating Aβ metabolism (Xu et al., 2006). In this study, we demonstrated that OVX for 5 weeks increased Aβ1-40 level in serum prepared from ICR female mice at 13–14 weeks old. In accordance with our finding, several clinical studies have demonstrated that plasma Aβ1-40 level is elevated in sporadic AD (Mayeux et al., 2003; Mehta et al., 2000) and that platelets are the major contributor of peripherally generated Aβ to the plasma (Colciaghi et al., 2004). Such abnormalities in the platelet amyloid precursor protein (APP) metabolism are observed in patients with mild cognitive impairment, as well as Alzheimer’s disease (Padovani et al., 2002). Recent study has indicated that circulating Aβ can across the blood brain barrier in both directions via RAGE and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein, and this may play an important role in the regulation of brain Aβ levels, and plaque formation (Zlokovic, 2004). In addition, circulating Aβ has been reported to cause in microvascular dysfunction and cerebral amyloid angiopathy, linked to cognitive impairment in the elderly (Gurol et al., 2006; Bibl et al., 2007). Therefore, although there is no sufficient evidence explaining a pivotal role of serum Aβ elevation in OVX mice, we assume that the OVX-induced increase in serum Aβ level may reflect the clinical observation in AD patients and further contribute to the neuropathological sequelae of AD.

In contrast, we could not detect the Aβ accumulation in the hippocampus of the OVX mice at 5 weeks after the operation. Similarly, recent data also indicated that OVX for 3 months, by which serum estrogen level were markedly decreased, did not affect estrogen level and Aβ plaque formation in the brains of AD model transgenic mice (APP23) overexpressing a mutant amyloid precursor protein transgene, but significantly decreased the brain estrogen level followed by Aβ plaque formation in APP23 mice with an aromatase gene knockout (Yue et al., 2005). In addition, it has been reported that reducing estrogen levels by blocking aromatase activity with letrozole, a reversible non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor, reduces the density of spines and synapses in hippocampal slice cultures (Kretz et al., 2004). These findings suggest that brain-derived estrogens, which are converted from C19 steroids by aromatase, have more important role in the Aβ clearance and the maintenance of neural environment than ovary-derived estrogens. In contrast, it was demonstrated that OVX for 10 weeks caused a 1.5-fold increase in total brain Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 levels compared to intact guinea pigs (Petanceska et al., 2000) and that OVX for 6 weeks resulted in a significant increase in the Aβ1-42 level and a trend toward an increase in Aβ1-40 peptides in the brains of AD model transgenic mice double overexpressing mutant APP and presenilin 1 transgenes (Zheng et al., 2002). Taken together, these findings suggest that brain Aβ accumulation depends on not only ovarian hormone decline but also the brain aromatase activity and the genetic background, and its regulation appears to be complex.

ABAD was found as an intramitochondrial Aβ-binding protein and was overexpressed in neurons affected in AD (Yan et al., 1997). In addition, we recently elucidated that the interaction of ABAD and Aβ caused mitochondrial dysfunction leading to neuronal apoptosis (Lustbader et al., 2004; Takuma et al., 2005). Interestingly, the present study demonstrated that OVX for 5 weeks increased neuronal ABAD level in the mouse hippocampus. Taken together with recent studies showing that estrogen protects neuronal cells from Aβ-induced apoptosis by regulating the expression of mitochondrial proteins (Yao et al., 2007; Nilsen et al., 2006), it is suggested that estrogen also directly regulates ABAD expression and that the cessation of negative regulation by OVX results in the overexpression of ABAD. On the other hand, it is also demonstrated that ABAD expression is increased in an Aβ-rich environment (Yan et al., 1997; He et al., 2002). However, we could not detect an increase in the hippocampal Aβ level in OVX mice. This evidence suggests that the regulation of ABAD expression is more sensitive to estrogen level than Aβ level. Moreover, in the behavioral performance of the OVX mice, we could never detect the memory impairment, which were measured by a novel objective recognition test and a contextual fear conditioning test, at 5 weeks after the operation (unpublished observation). Although further experiments are required to clarify the exact mechanism and pathological role of ABAD overexpression by ovarian hormone decline, this study gives the first evidence demonstrating that postmenopause-like hormone decline influences the expression of a cofactor critically magnifying Aβ-induced neuronal perturbation.

We focused our attention on RAGE in this study because its enhanced expression in an Aβ-rich environment has been reported (Yan et al., 1996; Lue et al., 2001; Deane et al., 2003). It has also been reported that RAGE is induced by 17β-estradiol and an estrogen receptor-α agonist, ethinyl estradiol, through activation of the transcription factor Sp-1 in human vascular endothelial cells (Tanaka et al., 2000; Mukherjee et al., 2005). Furthermore, this study demonstrated that OVX for 5 weeks did not affect RAGE level in the hippocampus in mice. Thus, it remains to be resolved whether brain levels of RAGE are increased or reduced by ovarian hormone decline.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that OVX causes increases in serum Aβ level and then ABAD level, but not RAGE, in the hippocampus of mice. In addition, we suggest that estrogen regulates the expression of neuronal ABAD in the hippocampus. These findings support the fact that the prevalence and incidence of AD are higher in postmenopausal women than men. We further propose that the elevation of Aβ and ABAD may be associated with memory deficit in postmenopausal women, as well as pathogenesis in early-stage AD. Therefore, more detailed studies, including behavioral analysis in later life after OVX, are needed to delineate the mechanism of the regulation of these AD-related molecules by ovarian hormone and to define the precise role of overexpressed Aβ and ABAD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant for the 21st Century COE Program (1640102 to Dr. K. Yamada) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (19390062 to Dr. K. Yamada, 18590050 to Dr. K. Takuma) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and grants from Takeda Science Foundation (Dr. K. Takuma) and the Smoking Research Foundation (Dr. K. Yamada), Japan. Dr. S.D. Yan was supported by the grant from the National Institute on Aging (PO1 AG17490).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2008.02.004.

References

- Basun H, Nilsberth C, Eckman C, Lannfelt L, Younkin S. Plasma levels of Aβ42 and Aβ40 in Alzheimer patients during treatment with the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor tacrine. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14:156–160. doi: 10.1159/000063605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibl M, Esselmann H, Mollenhauer B, Weniger G, Welge V, Liess M, Lewczuk P, Otto M, Schulz JB, Trenkwalder C, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J. Blood-based neurochemical diagnosis of vascular dementia: a pilot study. J Neurochem. 2007;103:467–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierhaus A, Humpert PM, Morcos M, Wendt T, Chavakis T, Arnold B, Stern DM, Nawroth PP. Understanding RAGE, the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Mol Med. 2005;83:876–886. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett J, Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Zou YS, Weidman E, Pinsky D, Nowygrod R, Neeper M, Przysiecki C, Shaw A, Migheli A, Stern D. Survey of the distribution of a newly characterized receptor for advanced glycation end products in tissues. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1699–1712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW, Xu HW, Stern D, McKhann G, Yan SD. Mitochondrial Aβ: a potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:2040–2041. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colciaghi F, Marcello E, Borroni B, Zimmermann M, Caltagirone C, Cattabeni F, Padovani A, Di Luca M. Platelet APP, ADAM 10 and BACE alterations in the early stages of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;62:498–501. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106953.49802.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordey M, Gundimeda U, Gopalakrishna R, Pike CJ. Estrogen activates protein kinase C in neurons: role in neuroprotection. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1340–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R, Yan SD, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, Welch D, Manness L, Lin C, Yu J, Zhu H, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Stern A, Schmidt AM, Armstrong DL, Arnold B, Liliensiek B, Nawroth P, Hofman F, Kindy M, Stern D, Zlokovic B. RAGE mediates amyloid-β peptide transport across the blood–brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. 2003;9:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nm890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzaki E, Takuma K, Himeno Y, Yoshida S, Funatsu Y, Kitahara Y, Mizoguchi H, Ib D, Koike K, Inoue M, Yamada K. Enhanced activity of hippo-campal BACE1 in a mouse model of postmenopausal memory deficits. Neurosci Lett. 2008;433:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S. The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurol ME, Irizarry MC, Smith EE, Raju S, Diaz-Arrastia R, Bottiglieri T, Rosand J, Growdon JH, Greenberg SM. Plasma beta-amyloid and white matter lesions in AD, MCI, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2006;66:23–29. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191403.95453.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XY, Merz G, Mehta P, Schulz H, Yang SY. Human brain short chain L-3-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase is a single-domain multifunctional enzyme. Characterization of a novel 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15014–15019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.15014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XY, Wen GY, Merz G, Lin D, Yang YZ, Mehta P, Schulz H, Yang SY. Abundant type 10 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the hippocampus of mouse Alzheimer’s disease model. Mol Brain Res. 2002;99:46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz O, Fester L, Wehrenberg U, Zhou L, Brauckmann S, Zhao S, Prange-Kiel J, Naumann T, Jarry H, Frotscher M, Rune GM. Hippocampal synapses depend on hippocampal estrogen synthesis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5913–5921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5186-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, Clemente AS, Velasco PT, Wood M, Viola KL, Klein WL. Aβ oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:796–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Shen Y, Yang LB, Lue LF, Finch C, Rogers J. Estrogen enhances uptake of amyloid β-protein by microglia derived from the human cortex. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1447–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue LF, Walker DG, Brachova L, Beach TG, Rogers J, Schmidt AM, Stern DM, Yan SD. Involvement of RAGE–microglial interactions in Alzheimer’s disease: in vivo and in vitro studies. Exp Neurol. 2001;171:29–45. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, Caspersen C, Chen X, Pollak S, Chaney M, Trinchese F, Liu S, Gunn-Moore F, Lue LF, Walker DG, Kuppusamy P, Zewier ZL, Arancio O, Stern D, Yan SS, Wu H. ABAD directly links Aβ to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux R, Honig LS, Tang MX, Manly J, Stern Y, Schupf N, Mehta PD. Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 and Alzheimer’s disease: relation to age, mortality, and risk. Neurology. 2003;61:1185–1190. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000091890.32140.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, Pirttilä T, Mehta SP, Sersen EA, Aisen PS, Wisniewski HM. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid β proteins 1–40 and 1–42 in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:100–105. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee TK, Reynolds PR, Hoidal JR. Differential effect of estrogen receptor α and β agonists on the receptor for advanced glycation end product expression in human microvascular endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1745:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Mukherjee TK. Bridging advanced glycation end product, receptor for advanced glycation end product and nitric oxide with hormonal replacement/estrogen therapy in healthy versus diabetic postmenopausal women: a perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1745:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen J, Chen S, Irwin RW, Iwamoto S, Brinton RD. Estrogen protects neuronal cells from amyloid β-induced apoptosis via regulation of mitochondrial proteins and function. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padovani A, Borroni B, Colciaghi F, Pettenati C, Cottini E, Agosti C, Lenzi GL, Caltagirone C, Trabucchi M, Cattabeni F, Di Luca M. Abnormalities in the pattern of platelet amyloid precursor protein forms in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:71–75. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petanceska SS, Nagy V, Frail D, Gandy S. Ovariectomy and 17β-estradiol modulate the levels of Alzheimer’s amyloid β peptides in brain. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:1317–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razmara A, Duckles SP, Krause DN, Procaccio V. Estrogen suppresses brain mitochondrial oxidative stress in female and male rats. Brain Res. 2007;1176:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuma K, Yao J, Huang J, Xu H, Chen X, Luddy J, Trillat AC, Stern DM, Arancio O, Yan SS. ABAD enhances Aβ-induced cell stress via mitochondrial dysfunction. FASEB J. 2005;19:597–598. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2582fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Yonekura H, Yamagishi S, Fujimori H, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H. The receptor for advanced glycation end products is induced by the glycation products themselves and tumor necrosis factor-α through nuclear factor-κB, and by 17β-estradiol through Sp-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25781–25790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Jacobs D, Stern Y, Marder K, Schofield P, Gurland B, Andrews H, Mayeux R. Effect of oestrogen during menopause on risk and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1996;348:429–432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell. 2005;120:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Wang R, Zhang YW, Zhang X. Estrogen, β-amyloid metabolism/ trafficking, and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:324–342. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, Roher A, Slattery T, Zhao L, Nagashima M, Morser J, Migheli A, Nawroth P, Stern D, Schmidt AM. RAGE and amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1996;382:685–691. doi: 10.1038/382685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SD, Fu J, Soto C, Chen X, Zhu H, Al-Mohanna F, Collison K, Zhu A, Stern E, Saido T, Tohyama M, Ogawa S, Roher A, Stern D. An intracellular protein that binds amyloid-β peptide and mediates neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1997;389:689–695. doi: 10.1038/39522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SD, Stern D. Mitochondrial dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease: role of amyloid-β peptide alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) Int J Exp Pathol. 2005;86:161–171. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2005.00427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SD, Zhu Y, Stern ED, Hwang YC, Hori O, Ogawa S, Frosch MP, Connolly ES, Jr, McTaggert R, Pinsky DJ, Clarke S, Stern DM, Ramasamy R. Amyloid β-peptide-binding alcohol dehydrogenase is a component of the cellular response to nutritional stress. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27100–27109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M, Nguyen TV, Pike CJ. Estrogen regulates Bcl-w and Bim expression: role in protection against β-amyloid peptide-induced neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1422–1433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2382-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue X, Lu M, Lancaster T, Cao P, Honda S, Staufenbiel M, Harada N, Zhong Z, Shen Y, Li R. Brain estrogen deficiency accelerates Aβ plaque formation in an Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19198–19203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505203102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Xu H, Uljon SN, Gross R, Hardy K, Gaynor J, Lafrancois J, Simpkins J, Refolo LM, Petanceska S, Wang R, Duff K. Modulation of Aβ peptides by estrogen in mouse models. J Neurochem. 2002;80:191–196. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic BV. Clearing amyloid through the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem. 2004;89:807–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.