Abstract

Neonatal hypoxia-ischemia (HI) induces immediate early gene (IEG) c-fos expression as well as neuron death. The precise role of IEGs in neonatal HI is unclear. We investigated the temporal and spatial pattern of c-Fos expression in postnatal day 7 mice following unilateral carotid ligation and exposure to 8% oxygen. Messenger RNA levels of c-fos quantitated by real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) increased nearly 40-fold (log 1.2 ± 0.4) in the ipsilateral hippocampus 3 h following neonatal HI then returned to basal levels within 12 h while no change was observed in c-jun mRNA. Frozen coronal brain sections were stained with cresyl violet or used for immunohistochemical detection of c-Fos, cleaved caspase-3, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the mature neuron marker NeuN. c-Fos immunoreactivity increased throughout the injured hippocampus 3 h after HI but became restricted to the CA2−3 subregion and the dentate gyrus (DG) at 6−12 h and declined by 24 h. In contrast, cleaved (activated) caspase-3 immunoreactivity was most abundant in the ipsilateral CA1 region at 3−6 h after neonatal HI, then became more prominent in CA2−3 and DG. Double labeling experiments showed c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity localized in spatially distinct neuron subpopulations. Prominent c-Fos immunoreactivity was observed in surviving CA2−3 and external granular DG neurons while robust cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was observed in pyknotic CA1, CA2−3 and subgranular DG neurons. The differential expression of c-Fos in HI-resistant hippocampal subpopulations versus cleaved caspase-3 in dying neurons suggests a neuroprotective role for c-Fos expression in neonatal HI.

Keywords: Hypoxia-ischemia, neonatal, c-fos, apoptosis, caspase

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of neurological disability in adults and there is growing appreciation that stroke can occur in infants and children as well (Lynch et al., 2002). In the developing brain, neonatal hypoxia-ischemia (HI) can lead to long-term cognitive and motor deficits, such as those seen in cerebral palsy (Ferriero, 2004). Neuronal death following neonatal HI can result from necrosis, apoptosis or a combination of death pathways (Northington et al., 2005). In the developing brain, cleavage and resultant activation of caspase-3 plays a prominent role in apoptotic death. Apoptotic death pathways can be further modulated by gene transcription but in neonatal HI, the role of immediate early genes (IEG) such as c-Fos remains unclear.

IEG expression is a common feature for many cellular processes including differentiation, proliferation, long-term plasticity, apoptosis and repair (Eferl et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006). c-Fos is the prototype of the Fos IEG family (c-Fos, FosB, Fos related proteins 1 and 2) which heterodimerizes with members of the Jun family (c-Jun, JunB, JunD) to form activator protein 1 (AP-1). Although Jun family members can homodimerize with each other, Fos:Jun heterodimers bind to the AP-1 consensus site, TCA(G/C)TGA, with a 30-fold higher affinity than the Jun:Jun homodimers (Rauscher, III et al., 1988). Thus, these many forms of AP-1 enable a broad array of transcriptional responses required for divergent processes including neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration (Raivich et al., 2006). Increased c-fos transcription and c-Fos protein expression are observed following insults such as excitotoxicity, trauma and axotomy (Smeyne et al., 1992; Herdegen et al., 2001). Focal HI also results in increased Fos protein and mRNA levels in adult (Nowak, Jr. et al., 1990; Uemura et al., 1991) and neonatal rodent brain (Gunn et al., 1990; Blumenfeld et al., 1992; Gubits et al., 1993; Munell et al., 1994; Aden et al., 1994) but it is unclear whether c-Fos promotes neuroprotection, neurodegeneration or a combination of both.

We have previously demonstrated that c-Fos is protective in a kainic acid (KA)-induced seizure model using mutant mice with a conditional hippocampal deletion of c-fos (Zhang et al., 2002) that is expressed beginning at 3 weeks of age. CA2−3 hippocampal neurons of mice selectively deficient in c-fos exhibited increased excitability and increased death in response to KA compared to wild-type mice with similar seizure severity suggesting that c-fos is neuroprotective. We hypothesized that c-Fos expression within the neonatal hippocampus following HI may also promote neuroprotection. Our current study compared the distribution of c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity to determine the spatial and temporal relationship between c-Fos expression and neuron apoptosis following neonatal HI insult.

METHODS

Animals

All mice were housed in microisolator cages with food and water provided ad libitum. The animal rooms were on a 14 h on-10 h off-light cycle. All animal procedures were approved by the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Neonatal hypoxia-ischemia

Litters of P7 mice were removed from the dam and kept warm using a heating pad. Mice were anesthetized using 3% halothane followed by a 3 mm midline cervical incision. The left carotid artery was exposed and coagulated using a bipolar electrocautery unit (Valleylab, Boulder, CO). The incision was then closed using topical surgical adhesive (Nexabond, Closure Medical Corp, Raleigh, NC). After a 2 h recovery period, the mice were then placed in a 600 ml chamber in which 8% O2/92% N2 was circulated for 45 min; normothermia was maintained by placing the hypoxia chamber in a 37°C waterbath. Peri-operative mortality was less than 20%. Mice were sacrificed one to 24 h following the onset of hypoxia. Control mice (designated as time 0) were anesthetized and underwent exploration of left carotid artery without cauterization then were sacrificed 2 h later. Tissue from the right and left hippocampus, cortex and striatum were isolated, snap-frozen and stored at −80°C in RNAse-free microfuge tubes prior to preparation for real-time PCR. For immunohistochemical studies, whole brains were immersion-fixed in Bouin's fixative overnight at 4°C then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mmol/l Na2HPO4, 1.4 mmol/l KH2PO4 , 140 mmol/l NaCl, 2.7 mmol/l KCl, pH 7.2 ), frozen in liquid 1,1,1,2-tetra-fluoroethane on dry ice and sectioned by cryostat into 10 micron sections.

Real time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (1 μg) was incubated with 200 ng random hexamers, 0.5 mM dNTPs, and RNase-free water at 65°C for 10 min (all from Invitrogen). Then, 5 ×first strand buffer, 5 mM DTT, 40 U RNAseOUT, and 200 U SuperScript III was added and the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min, at 50°C for 60 min, at 70°C for 15 min, and at 4°C for 10 min.

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using an ABI 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). Assays for target cDNA levels were performed using TaqMan MGB probes labeled with FAM dye (ABI Assay-on-Demand Gene Expression assays) in a 20 μl reaction containing 2 μl of cDNA, ROX passive reference dyes and TaqMan Universal PCR mix (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). The specific primer sets used and their part number are: c-fos (Mm00_ml) and c-jun (Mm00658541_m1). Levels of 18S ribosomal cDNA were assayed in parallel reactions using TaqMan MGB probes labeled with VIC dye (Applied Biosystems #4319413E). All assays were performed in triplicate.

Experimental results were analyzed using Applied Biosystems Sequence Detection Software (Version 1.3.1.22). Relative quantities of c-fos and c-jun mRNAs were established by normalizing their levels to that of 18S in the same cDNA; data were expressed relative to time 0 animals. No template controls were performed in parallel to verify an absence of contamination. Each data point represents the mean log-change of c-fos or c-jun mRNA from at least 3 animals per time point.

Immunohistochemistry

Adjacent sections were either stained with cresyl violet for morphological analysis or processed for immunohistochemical studies as previously described (Ness et al., 2006; Srinivasan et al., 1998). Primary antibodies used to assess the effect of HI included rabbit anti-c-Fos (SC52, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-cleaved “activated” caspase-3 (Asp175, #9691, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), mouse anti-NeuN to identify neurons (#MAB377, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), an astrocyte marker (G9269; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Slides were rinsed 3 times in PBS, then incubated 30 min at room temperature in PBS-blocking buffer (PBS-BB; 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% powdered skim milk, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS). Incubation with primary antibodies diluted in PBS-BB was performed overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed 3 times with PBS followed by incubation with donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:2000, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) at room temperature for 30 min. Direct tyramide signal amplification (TSA; Perkin-Elmer Life Science Products, Boston, MA) was performed according to manufacturer's instruction. When double staining was performed using primary antibodies generated from the same species, detection of the second primary antibody was performed using anti-rabbit IgG directly conjugated to Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) (Shindler et al., 1996). Cell nuclei were labeled with bisbenzimide (Hoeschst dye 33,258; Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Quantitation of immunohistochemical labeling

Prior studies of neonatal HI from our laboratory have shown most consistent injury in the anterior hippocampus (Ness et al., 2006) so c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 staining were assessed in sections from the anterior hippocampus corresponding to plates #44−45 in a mouse brain atlas (Franklin et al., 1997). Specific regions of the hippocampus (CA1, CA2−3, dentate gyrus (DG), and the stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare, identified as STR in Figure 4) were outlined using ImagePro version 4.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc. Silver Spring, MD). The mean number of individual c-fos or cleaved caspase-3 immunopositive cells and double-labeled cells from each region were then counted for each animal. The mean number of immunopositive c-Fos and caspase-3 cells were calculated from at least 3 animals per time point.

Figure 4. Quantification of c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity within regions of the ipsilateral hippocampus after neonatal HI.

The total numbers of cells per section within the ipsilateral hippocampus with c-Fos immunoreactivity (Fig 4A, solid bars) or cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity (Fig 4A, hatched bars) were counted 0−48 h after neonatal HI. At least 3 animals from separate litters were used for each time point (bar = mean ± SD). c-Fos immunoreactivity at 3 h was significantly increased compared to c-Fos at Time 0 and to cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity at 3 h (*p<0.05). Cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was also significantly increased relative to Time 0 cleaved caspse-3 at 12 and 24 h (**p<0.01). Analysis of the time course within hippocampal sub-regions (CA1, CA2−3, DG and STR) identified significant increases in c-Fos immunoreactivity 3 h after neonatal HI for the CA1 and STR regions (Fig 4B, *** p<0.001). In contrast, significant increases in cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity (Fig 4C) were not observed until 6h following neonatal HI in the CA1 (**p<0.01), 12 h in the CA2−3 region (**p<0.01) and DG (*p<0.05) and persisted until 24 h in the DG (***p<0.001).

Statistical analysis

Each time point was compared to time 0 using one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett multiple comparisons test. Significance was set at P< 0.05.

RESULTS

Neonatal HI causes selective increases in c-fos mRNA

We quantitated levels of c-fos mRNA from the ipsilateral hippocampus using real time PCR. c-fos mRNA was normalized to 18S mRNA from each sample, then expressed as a log increase compared to control animals subjected to sham operation without hypoxia (Time 0). As illustrated in Figure 1, c-fos mRNA peaked 3 h after neonatal HI with a mean log increase of 1.2 ± 0.4 (Figure 1; black bars, n=5; mean fold-increase 39.7 ± 26.5) compared to Time 0 control animals. Increases in c-fos mRNA persisted until 6 h after neonatal HI. In contrast, no change in hippocampal c-jun mRNA expression was observed at any time point. These results show that neonatal HI leads to abundant transcription of c-fos but not c-jun in the ipsilateral hippocampus so we next examined c-Fos protein expression following neonatal HI.

Figure 1. Neonatal hypoxia-ischemia causes a rapid, transient increase of c-fos mRNA in the ipsilateral hippocampus.

Total RNA was prepared from left hippocampal tissue collected 0−24 h following neonatal HI. Real time PCR was used to quantitate mRNA levels of c-fos and c-jun which were normalized to 18S mRNA in each sample, then changes in c-fos and c-jun mRNA were expressed as log change relative to Time 0 (defined as log 0 in each experiment). The bars represent the mean log change ± SEM of c-fos mRNA (solid bars) and c-jun mRNA (open bars) of 3−5 animals per time point.

Neonatal HI leads to increased c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity in spatially distinct neuron subpopulations

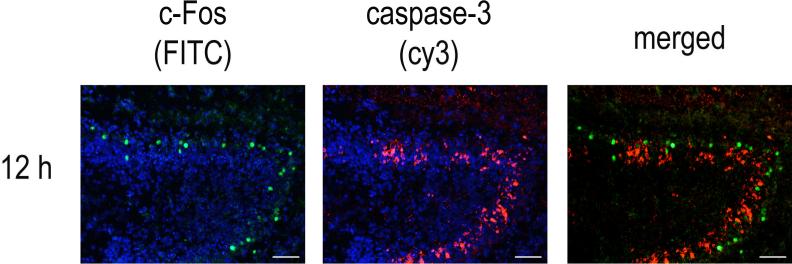

c-Fos can promote death or survival depending on the cell type and stimulus while cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity is a marker of cells undergoing apoptotic death. Therefore we compared immunoreactivity of c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 in neonatal mice at varying times following neonatal HI. Little or no c-Fos or cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was detectable in control animals subjected to sham-operation only (Time 0; Figure 2A; c-Fos, green FITC; cleaved caspase-3, orange cy3) or 1 h after neonatal HI (data not shown). Three h following HI, a robust increase in c-Fos immunoreactivity was observed throughout the ipsilateral hippocampus, particularly the stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare. In contrast, cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity at this time point localized to scattered pyramidal neurons of CA1 and CA 2−3 (Figure 2A). Double labeling experiments demonstrated cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity in less than 5% of c-Fos immunopositive cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. c-Fos immunoreactivity does not co-localize with cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity after neonatal HI.

Seven-day old B57BL6/J mice were subjected to left carotid ligation, allowed to recover for 2 h, then exposed to 8% O2 for 45 min and sacrificed at the indicated times. The Time 0 animal was subjected to a sham operation without carotid ligation, then sacrificed 2 h later. Frozen sections underwent immunofluorescence staining as described in the methods. Figure 2A: A time course of 0−48 h is shown with c-Fos immunoreactivity was detected with FITC (green) and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was detected with cy3 (red). Scale bar = 200 microns. Figure 2B: Higher magnification of the CA1 region is shown to illustrate the distinct localization of c-Fos (left column) and cleaved caspase-3 (middle column) within the CA1 region at 3, 6 and 12 h after neonatal HI. Nuceli are counterstained with bisbenzamide. Merged photomicrographs of c-Fos and cleaved caspase immunoreactivity are shown in the right column. (Scale bar = 50 micron). Figure 2C: Higher magnification of the DG at 12 h (scale bar = 100 micron) illustrates differential distribution of c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity within the granule neurons of the DG.

Six h after neonatal HI, c-Fos localized to DG granule neurons and pyramidal neurons within the CA3 and to a lesser extent CA1 region within the ipsilateral hippocampus; 2 animals out of 7 also exhibited a small increase in c-Fos immunoreactivity in the contralateral CA1 region (data not shown). c-Fos immunoreactivity was observed only in non-pyknotic neurons whereas cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was most abundant in pyknotic pyramidal neurons of CA1 and CA 2−3 (Figure 2B, showing higher magnification of c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity in the CA1 region counterstained with bisbenzamide). Twelve h after neonatal HI, increased c-Fos immunoreactivity persisted within the CA2−3 region; no c-Fos immunoreactivity was observed in the contralateral hippocampus of any animal. Cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was also found diffusely throughout the CA2−3 pyramidal neuron layer but did not co-localize with c-Fos, Within the DG, c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 were also expressed in distinct neuron subpopulations. A discrete layer of c-Fos immunoreactive neurons outlined the external layer of the DG granule neurons whereas cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity predominated in the internal layer of DG granule neurons (Fig 2C).

c-Fos immunoreactivity decreased markedly by 24 h with only scattered immunoreactive neurons found in the remaining pyramidal neurons. Low levels of c-Fos immunoreactivity were detected at 48 h after neonatal HI in surviving neurons within the CA1 and CA2−3 regions. In contrast, cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was detectable through 48 h within a subpopulation of CA2−3 and DG neurons that was distinct from those with c-Fos immunopositivity.

To verify that the increased c-Fos immunoreactivity was in neurons, we performed double staining with c-Fos and NeuN, a marker for mature neurons, and GFAP to identify astrocytes. At 3, 6 and 12 h after neonatal HI, c-Fos immunostaining co-localized with NeuN but not GFAP positive cells indicating the selective expression of c-Fos in neurons (Fig 3, left column) but not in astrocytes (Fig 3, right column).

Figure 3. c-Fos immunoreactivity is restricted to neurons after neonatal HI.

Frozen sections from animals 3, 6 and 12 h after neonatal HI were immunostained with c-Fos detected with cy3 (red) and then double labeling was performed using antibodies against NeuN (detected with FITC, in green; left column) or with antibodies against GFAP detected with FITC (right column). Scale bar = 100 microns.

Neuron loss in the hippocampus was detectable in the CA1 region as early as 6 h after neonatal HI and by 24 h resulted in loss of most of the CA1 layer with punctuate regions of neuron loss in the CA2−3 and DG by 48 h. Interestingly, regions with highest c-Fos expression remained intact which is consistent with prior studies in our laboratory and others showing that CA2−3 and DG neurons are relatively resistant to neonatal HI compared to the CA1 region (Ness et al., 2006).

We further verified our observations by counting c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactive cells within the ipsilateral hippocampus 0−48 h following neonatal HI from at least 3 animals per time point. We took care to ensure that cell counts from each animal were obtained from the same level within the anterior hippocampus corresponding the plates #44−45 from a standard mouse brain atlas (Franklin et al., 1997). As shown in Fig 4A, there was a rapid increase in c-Fos immunoreactivity (black bars) at 3 h with a mean 499 ± 98 (mean ± SEM, n = 5) cells per section within the ipsilateral hippocampus which was significantly increased compared to c-Fos immunoreactivity at Time 0 (2.8 ± 6.3, p <0.05). There was also a significant increase in the number of c-Fos versus cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactive cells at 3 h (57 ± 26, n=7, hatched bars, p<0.001). Although there were slightly fewer cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactive cells overall, there was a significant increase in cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactive cells at 12 h (189 ± 44 cells, n=5, p<0.01) and 24 h (187 ± 36, n=5, p<0.01) compared to cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity at Time 0 (1.5 ± 0.7, n=4).

We further characterized the distribution of c-Fos and cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactive cells within discrete regions of the ipsilateral hippocampus following neonatal HI. c-Fos immunoreactive cells were widely distributed throughout the hippocampus, particularly CA1, stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare of the ipsilateral hippocampus 3 h after neonatal HI but became restricted to the CA2−3 and DG regions at 6−12 h (Fig 4B). c-Fos immunoreactivity typically preceded the onset of cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity within a given region. However, no cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was detected in the stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare despite prominent c-Fos immunoreactivity in that region at 3 h. Analysis of the time course within each hippocampal sub-region identified sharp increases in c-Fos immunoreactivity at 3 h in the CA1 and stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare regions (Fig 4B, p<0.001) with lower but sustained c-Fos immunoreactivity in the ipsilateral CA2−3 and DG. In contrast, significant increases in cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity (Fig 4C) were not observed in the CA1 region until 6 h following neonatal HI (p<0.01), 12 h in the CA2−3 region (p<0.01) and in DG beginning at 12 h (p<0.05) through 24 h (p<0.001).

Taken together, these studies show that HI in the neonatal mouse results in rapid, transient increase of hippocampal c-Fos mRNA and immunoreactivity in concert with a slower, sustained increase in cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity that occurs in spatially distinct neuron subpopulations within the ipsilateral hippocampus.

DISCUSSION

In this report we show that neonatal mice subjected to HI at P7 exhibit a robust, transient increase in c-Fos immunoreactivity in neurons spatially distinct from those undergoing apoptosis. c-Fos immunoreactivity precedes cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity within a given hippocampal region. However, c-Fos immunoreactivity is most prominent in neuron subpopulations that are resistant to neonatal HI, suggesting that c-Fos may induce survival-promoting genes.

We used quantitative real time PCR to demonstrate that neonatal HI in mice induces a greater than 10-fold increase in hippocampal c-fos mRNA. Similar findings of HI-induced c-fos expression in neonatal rat brain have been reported using non-quantitative methods (Blumenfeld et al., 1992; Gubits et al., 1993; Aden et al., 1994; Munell et al., 1994; Jiang et al., 2005). We did not find a significant change in c-jun expression within 24 h after neonatal HI, similar to observations by another group (Bona et al., 1997) but in contrast to other investigators who found increased c-jun transcription within hours of neonatal HI in rats (Gubits et al., 1993; Munell et al., 1994). These differing observations in neonatal HI-induced c-jun transcription may be due to strain or species differences in IEG expression. Alternatively, c-jun transcription may be a slower onset process occurring in neurons undergoing delayed death (Dragunow et al., 1994; McGahan et al., 1998; Walton et al., 1998).

In C57BL/6J mice, the ipsilateral hippocampus is selectively vulnerable to neonatal HI so we concentrated our analysis on that region. Similar to previous observations by our laboratory and others (Sheldon et al., 1998; Ness et al., 2006; Towfighi et al., 1998), we found the CA1 region to be particularly susceptible to neonatal HI-induced death while the CA2−3 and DG neurons were relatively resistant to this form of injury. Three hours after neonatal HI, c-Fos immunoreactivity increased diffusely in the ipsilateral hippocampus in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare and stratum radiatum of the CA regions plus the molecular layers of the DG but by 12 h, c-Fos is selectively increased in non-pyknotic CA2−3 pyramidal neurons and DG granule neurons that are negative for cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity.

Prior studies have demonstrated increased c-Fos protein expression in neonatal rat brain following HI (Gunn et al., 1990; Blumenfeld et al., 1992; Gubits et al., 1993; Munell et al., 1994; Aden et al., 1994) but to our knowledge no prior studies have been performed in neonatal mice that examine c-Fos induction in conjunction with cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity. Our finding that c-Fos and active caspase-3 localize in distinct neuron subpopulations can be explained by (1) c-Fos expression precedes caspase-3 cleavage or occurs only in neurons undergoing caspase-3-independent death; or (2) c-Fos induction promotes neuron survival by triggering expression of neuroprotective genes. If c-Fos is a precursor to HI-induced cell death, then CA1 pyramidal neurons would be expected to have the highest c-Fos immunoreactivity. We did find increased c-Fos immunopositive cells within the CA1 region at 3 h, but primarily in cells outside of the pyramidal neuron layer. At 6−48 h after HI, lower levels of c-Fos expression were identified in the CA1 region within clusters of surviving CA1 pyramidal neurons. It is unlikely that a peak of early c-Fos expression was missed as no c-Fos immunoreactivity was observed in animals sacrificed 1 h after neonatal HI.

The function of c-Fos in balancing life versus death depends highly on the specific environmental stimulus and/or cell types involved (Akins et al., 1996; Lu et al., 1997; Karin et al., 1997; Shaulian et al., 2002). Increased c-fos transcription or c-Fos immunoreactivity following HI in the immature brain has been suggested to promote neuron death (Nozaki et al., 1992; Oorschot et al., 2000; Binienda et al., 1994). In other studies, c-Fos is selectively expressed in neurons surviving mild to moderate HI injury (Gunn et al., 1990) and in the spared neurons of the contralateral hemisphere (Gubits et al., 1993; Aden et al., 1994; Dragunow et al., 1994; Munell et al., 1994). We also observed small areas of increased c-Fos immunoreactivity in the contralateral hippocampus CA1 region in two of our animals but because it was an infrequent observation we did not quantify it further.

Additional evidence for a neuroprotective role of c-Fos in stroke is found in an ultrastructural study of hippocampal neurons of adult gerbils following transient ischemia and reperfusion (Tomimoto et al., 1999). In this study, CA3 neurons with reversible injury exhibited increased c-Fos expression while dying CA1 neurons had no c-Fos immunoreactivity. Similarly, increased c-Fos was identified in ipsilateral DG and CA2−4 neurons 1−3 hr after transient forebrain ischemia in adult rats (Cho, 2001).

Treatments reported to be neuroprotective in neonatal HI have shown conflicting results with respect to c-Fos induction. c-Fos is proposed to be a death-promoting molecule in several pharmacologic studies which demonstrate concomitant decreases in c-Fos expression and neonatal HI-induced injury following treatment with kynurenic acid, an endogenous excitatory amino acid receptor antagonist, (Nozaki et al., 1992), diazoxide, an activator of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels (Jiang et al., 2005) or dexamethasone (Ekert et al., 1997). However, other treatment approaches suggest c-Fos expression is protective in stroke. Activation of adenosine receptors by theophylline reduced infarct size by nearly 50% in neonatal HI in concert with upregulation of c-fos mRNA (Bona et al., 1997). In adult transient forebrain ischemia, administration of N-acetyl-O-methyldopamine protected CA1 neurons from injury and increased c-Fos expression in that region (Cho, 2001). Intraventricular infusion of antisense oligonucelotides to c-fos prior to carotid occlusion in adult rats also clearly reduced the number of c-Fos positive cells and resulted in increased infarct size (Zhang et al., 1999). In another adult stroke model, the protective effects of hypothermia were associated with increased cortical c-Fos immunoreactivity 3 h after re-perfusion (Akaji et al., 2003). These divergent findings with respect to the role of c-Fos in HI-induced injury may be due to strain-, cell- or stimulus-specific differences in IEG regulation.

Other Fos-related proteins are also postulated to play a neuroprotective role. In an adult middle cerebral artery occlusion model, immunoreactivity of Fos-related antigen FRA-2 was highly upregulated 6 h later in the dentate gyrus while c-Fos was increased in the CA3 region (Butler et al., 2004). Similar to our findings, these authors observed increased c-Fos expression initially in the hypoxia-susceptible CA1 region followed by a delayed increase in the resistant CA3-region. They also observed c-Fos and FRA-2 in other ischemia-resistant neurons although there was little co-localization of c-Fos and FRA-2. The role of Fos-related family members has not yet been investigated in neonatal HI.

A c-fos-deficient animal strain has been developed but these animals develop osteopetrosis due to a hematopoietic defect (Wang et al. 1992). These animals have been shown to be resistant to cryotherapy-induced injury of the cerebral cortex in 4−6 week old animals (Steinbach et al. 1999). To our knowledge, no studies have been published examining the influence of c-fos deficiency in a stroke model at any age. Development of new powerful mouse models has allowed selective, inducible deficiency of c-fos using c-fos gene flanked by loxP sites by homologous recombination (c-fosf/f mice). By cross-breeding with CaMKIIα-cre transgenic mice, animals are generated that have selective deficiency of c-Fos in the hippocampus. These animals are resistant to seizure-induced hippocampal injury (Zhang et al. 2002) suggesting that c-Fos is playing a neuroprotective role in excitotoxic neuron death. It would be interesting to determine whether these animals are equally resistant to HI-induced neuron death. However, neonatal HI is not testable in this model as CaMKIIα transcription does not begin until 3 weeks of age, so selective c-Fos deficiency is not inducible in this model until early adolescence.

Prior studies in our laboratory and others (Ness et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2001; Gibson et al., 2001; Liou et al., 2003) have highlighted the importance of apoptosis in neonatal HI. Caspase-3 activation is a particularly prominent component of HI-induced neuronal death in the immature brain (Wang et al., 2001; Zhu et al., 2005). Our findings of increased c-Fos expression in CA2−3 and DG neurons without cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity suggest that c-Fos is upregulated in neurons resistant to caspase-3 mediated death. Further studies tracking the fate of individual neurons plus development of mouse strains with inducible c-Fos expression during the neonatal period will be critical in determining the role of c-Fos in neonatal HI.

Acknowledgements

Supported by fellowships and grants from NIH K08 NS043220 and NIH 1 K12 HD043397 (JMN), R01 NS048353 (SLC), NS35107 and NS41962 (KAR) and Epilepsy Foundation (JZ). We also thank UAB Neuroscience Core Facilities (NS47466 and NS57098) for technical support.

References

- Aden U, Bona E, Hagberg H, Fredholm BB. Changes in c-fos mRNA in the neonatal rat brain following hypoxic ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 1994;180:91–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaji K, Suga S, Fujino T, Mayanagi K, Inamasu J, Horiguchi T, Sato S, Kawase T. Effect of intra-ischemic hypothermia on the expression of c-Fos and c-Jun, and DNA binding activity of AP-1 after focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Brain Res. 2003;975:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins PT, Liu PK, Hsu CY. Immediate early gene expression in response to cerebral ischemia. Friend or foe? Stroke. 1996;27:1682–1687. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binienda Z, Scallet AC. The effects of reduced perfusion and reperfusion on c-fos and HSP-72 protein immunohistochemistry in gestational day 21 rat brains. Int J Dev.Neurosci. 1994;12:605–610. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld KS, Welsh FA, Harris VA, Pesenson MA. Regional expression of c-fos and heat shock protein-70 mRNA following hypoxia-ischemia in immature rat brain. J Cereb.Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:987–995. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bona E, Aden U, Gilland E, Fredholm BB, Hagberg H. Neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia: the effect of adenosine receptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1327–38. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler TL, Pennypacker KR. Temporal and regional expression of Fos-related proteins in response to ischemic injury. Brain Res Bull. 2004;63:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Park EM, Kim Y, Liu N, Gal J, Volpe BT, Joh TH. Early c-Fos induction after cerebral ischemia: a possible neuroprotective role. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:550–556. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M, Beilharz E, Sirimanne E, Lawlor P, Williams C, Bravo R, Gluckman P. Immediate-early gene protein expression in neurons undergoing delayed death, but not necrosis, following hypoxic-ischaemic injury to the young rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;25:19–33. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl R, Wagner EF. AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat.Rev.Cancer. 2003;3:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekert P, MacLusky N, Luo XP, Lehotay DC, Smith B, Post M, Tanswell AK. Dexamethasone prevents apoptosis in a neonatal rat model of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) by a reactive oxygen species-independent mechanism. Brain Res. 1997;747:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N.Engl.J.Med. 2004;351:1985–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; Sand Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson ME, Han BH, Choi J, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Parsadanian M, Holtzman DM. BAX contributes to apoptotic-like death following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia: evidence for distinct apoptosis pathways. Mol Med. 2001;7:644–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubits RM, Burke RE, Casey-McIntosh G, Bandele A, Munell F. Immediate early gene induction after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;18:228–38. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90194-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn AJ, Dragunow M, Faull RL, Gluckman PD. Effects of hypoxia-ischemia and seizures on neuronal and glial-like c-fos protein levels in the infant rat. Brain Res. 1990;531:105–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T, Waetzig V. AP-1 proteins in the adult brain: facts and fiction about effectors of neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Oncogene. 2001;20:2424–2437. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang KW, Yu ZS, Shui QX, Xia ZZ. Activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels prevents the cleavage of cytosolic mu-calpain and abrogates the elevation of nuclear c-Fos and c-Jun expressions after hypoxic-ischemia in neonatal rat brain. Brain Res Mol.Brain Res. 2005;133:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Liu Z, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr.Opin.Cell Biol. 1997;9:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou AK, Clark RS, Henshall DC, Yin XM, Chen J. To die or not to die for neurons in ischemia, traumatic brain injury and epilepsy: a review on the stress-activated signaling pathways and apoptotic pathways. Prog.Neurobiol. 2003;69:103–142. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XC, Tortella FC, Ved HS, Garcia GE, Dave JR. Neuroprotective role of c-fos antisense oligonucleotide: in vitro and in vivo studies. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2925–2929. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709080-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JK, Hirtz DG, DeVeber G, Nelson KB. Report of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109:116–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGahan L, Hakim AM, Nakabeppu Y, Robertson GS. Ischemia-induced CA1 neuronal death is preceded by elevated FosB and Jun expression and reduced NGFI-A and JunB levels. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;56:146–161. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munell F, Burke RE, Bandele A, Gubits RM. Localization of c-fos, c-jun, and hsp70 mRNA expression in brain after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Brain Res Dev.Brain Res. 1994;77:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness JM, Harvey CA, Strasser A, Bouillet P, Klocke BJ, Roth KA. Selective involvement of BH3-only Bcl-2 family members Bim and Bad in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Brain Res. 2006;1099:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northington FJ, Graham EM, Martin LJ. Apoptosis in perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury: how important is it and should it be inhibited? Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;50:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak TS, Jr, Ikeda J, Nakajima T. 70-kDa heat shock protein and c-fos gene expression after transient ischemia. Stroke. 1990;21:III107–III111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki K, Beal MF. Neuroprotective effects of L-kynurenine on hypoxia-ischemia and NMDA lesions in neonatal rats. J Cereb.Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:400–407. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oorschot DE, Black MJ, Rangi F, Scarr E. Is Fos protein expressed by dying striatal neurons after immature hypoxic-ischemic brain injury? Exp.Neurol. 2000;161:227–233. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Behrens A. Role of the AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun in developing, adult and injured brain. Prog.Neurobiol. 2006;78:347–363. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauscher FJ, III, Voulalas PJ, Franza BR, Jr, Curran T. Fos and Jun bind cooperatively to the AP-1 site: reconstitution in vitro. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1687–1699. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12b.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat.Cell Biol. 2002;4:E131–E136. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA, Sedik C, Ferriero DM. Strain-related brain injury in neonatal mice subjected to hypoxia-ischemia. Brain Res. 1998;810:114–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00892-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindler KS, Roth KA. Double immunofluorescent staining using two unconjugated primary antisera raised in the same species. J.Histochem.Cytochem. 1996;44:1331–1335. doi: 10.1177/44.11.8918908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeyne RJ, Schilling K, Robertson L, Luk D, Oberdick J, Curran T, Morgan JI. fos-lacZ transgenic mice: mapping sites of gene induction in the central nervous system. Neuron. 1992;8:13–23. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90105-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan A, Roth KA, Sayers RO, Shindler KS, Wong AM, Fritz LC, Tomaselli KJ. In situ immunodetection of activated caspase-3 in apoptotic neurons in the developing nervous system. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:1004–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomimoto H, Takemoto O, Akiguchi I, Yanagihara T. Immunoelectron microscopic study of c-Fos, c-Jun and heat shock protein after transient cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Acta Neuropathol.(Berl) 1999;97:22–30. doi: 10.1007/s004010050951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towfighi J, Mauger D. Temporal evolution of neuronal changes in cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in developing rats: A quantitative light microscopic study. Develop Brain Res. 1998;109:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura Y, Kowall NW, Moskowitz MA. Focal ischemia in rats causes time-dependent expression of c-fos protein immunoreactivity in widespread regions of ipsilateral cortex. Brain Res. 1991;552:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90665-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M, MacGibbon G, Young D, Sirimanne E, Williams C, Gluckman P, Dragunow M. Do c-Jun, c-Fos, and amyloid precursor protein play a role in neuronal death or survival? J Neurosci.Res. 1998;53:330–342. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980801)53:3<330::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Karlsson JO, Zhu C, Bahr BA, Hagberg H, Blomgren K. Caspase-3 activation after neonatal rat cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Biol Neonate. 2001;79:172–9. doi: 10.1159/000047087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang D, McQuade JS, Behbehani M, Tsien JZ, Xu M. c-fos regulates neuronal excitability and survival. Nat.Genet. 2002;30:416–420. doi: 10.1038/ng859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang L, Jiao H, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Lou D, Katz JL, Xu M. c-Fos Facilitates the Acquisition and Extinction of Cocaine-Induced Persistent Changes. J.Neurosci. 2006;26:13287–13296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3795-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Widmayer MA, Zhang B, Cui JK, Baskin DS. Suppression of post-ischemic-induced fos protein expression by an antisense oligonucleotide to c-fos mRNA leads to increased tissue damage. Brain Res. 1999;832:112–117. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Wang X, Xu F, Bahr BA, Shibata M, Uchiyama Y, Hagberg H, Blomgren K. The influence of age on apoptotic and other mechanisms of cell death after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Cell Death.Differ. 2005;12:162–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]