Abstract

The synthesis and properties of two responsive magnetoluminescent iron oxide nanoparticles for dual detection of DNA by MRI and luminescence spectroscopy are presented. These magnetoluminescent agents consist of iron oxide nanoparticles conjugated with metallointercalators via a polyethylene glycol linker. Two metallointercalators were investigated: Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz), which turns on upon DNA intercalation, and Eu-DOTAm-Phen, which turns off. The characteristic light-switch responses of the metallointercalators are not affected by the iron oxide nanoparticles; upon binding to DNA the luminescence of the ruthenium complexes increases by ca. 20 fold, whereas that of the europium complex is > 95 % quenched. Additionally, the 17–20 nm magnetite cores, having permeable PEG coatings and stable dopamide anchors, render the two constructs efficient responsive contrast agents for MRI with unbound longitudinal and transverse relaxivities of 12.4 – 9.2 mM−1Fes−1 and 135 – 128 mM−1Fes−1, respectively. Intercalation of the metal complexes in DNA results in the formation of large clusters of nanoparticles with a resultant decrease of both r1 and r2 by 32 – 63 % and 24 – 38 %, respectively. The potential application of these responsive magnetoluminescent assemblies and their reversible catch-and-release properties for the purification of DNA is presented.

Keywords: iron oxide nanoparticles, luminescence, DNA intercalator, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, lanthanide

INTRODUCTION

Multimodal nanocomposite probes – nanoparticle assemblies that enable imaging by two or more techniques – have become increasingly prevalent over the last decade. Of these, magnetoluminescent1–8 and magnetoplasmonic9–10 agents are receiving the most attention due to their ability to combine two widespread techniques, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and confocal or dark field microscopy, which are complementary in terms of three-dimensional imaging capability and spatial resolution, respectively. Particulate magnetoluminescent probes are most often composed of superparamagnetic metallic nanoparticles, preferentially magnetite or maghemite, which confers to the assembly the high transverse relaxivity necessary for MR imaging. The metallic crystals are either directly functionalized with luminescent dyes, or the dyes are embedded in a surrounding silica matrix. Organic dyes are employed most commonly in these assemblies due to their commercial availability and high quantum yield. More recently, complexes of ruthenium11–14 and luminescent lanthanides (terbium and europium)15–16 have also been reported. These offer the notable advantage of long luminescence lifetimes that enable time-gated detection and thus improved sensitivity in complex biological media. More importantly, their large Stokes shifts also minimize intrananoparticle luminescence quenching. This is particularly beneficial as recent studies by Simard have indicated that decreased luminescence of magnetoluminescent assemblies containing organic dyes is not due to quenching from the iron oxide nanoparticles but to aggregation of the dyes in the silica matrix.17 This quenching is substantially reduced with the use of dyes with long luminescence lifetimes, such as the ruthenium and lanthanide complexes used herein. Although the design and behavior of magnetoluminescent probes are increasingly understood, all current work has so far focused on non-responsive probes that do not report on the presence or absence of specific, targeted biomarkers. Aside from our recent example of a dual-responsive magnetoplasmonic assembly,18 no dual responsive multimodal nanoparticle has yet been reported. Yet, as the increasing number of publications on particulate-responsive MRI contrast agents indicates, such probes are particularly sought after by the biomedical community. Herein we report the synthesis and evaluation of two responsive magnetoluminescent nanocomposites that detect dsDNA by MRI, as determined by a change in longitudinal and transverse relaxivities, and by luminescence.

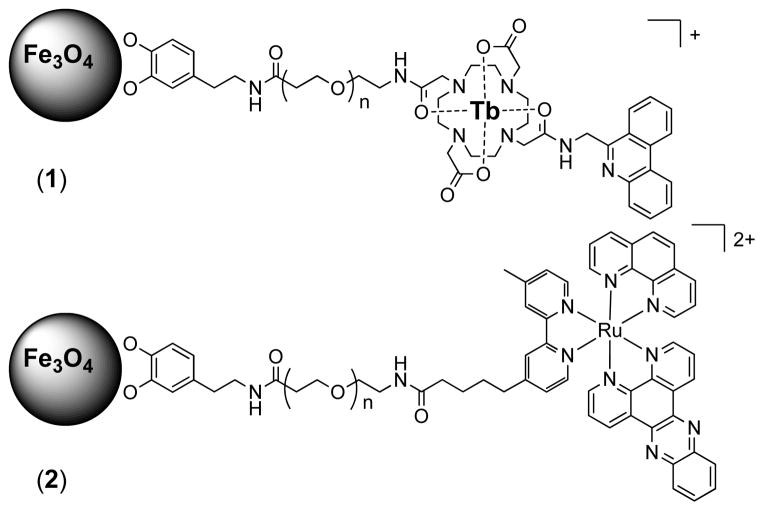

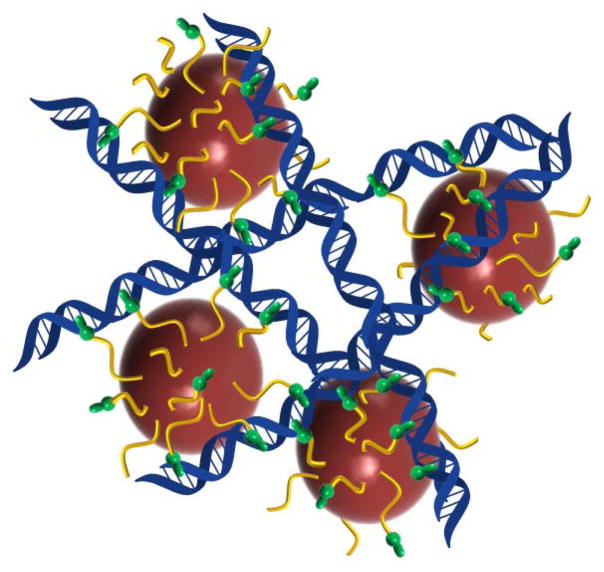

The responsive magnetoluminescent probes, Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAm-Phen (1) and Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2), consist of a magnetite core with high saturation magnetization functionalized with either a lanthanide or a ruthenium metallointercalator bound to the iron oxide surface via a stable dopamide anchor (Figure 1).19 Both metallointercalators behave as DNA light-switches. The time-gated luminescence of europium and terbium complexes of DOTAm-Phen are quenched > 95 % upon intercalation of the phenanthridine antenna in the DNA base stack. This observation correlates to photoelectron transfer of guanosine, and to a lesser extent, adenosine, to the phenanthridine.20–25 As a result Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAm-Phen (1) is expected to behave as a turn-off magnetic light switch. On the other hand, the luminescence of the ruthenium dppz complex in aqueous solution increases over 10 fold upon intercalation in the major groove of dsDNA,26–34 such that Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2) was designed as a turn-on light switch. Importantly, both magnetoluminescent probes were also designed to behave as responsive MRI contrast agents. Intercalation of the phenanthridine and dppz ligands of (1) and (2) in the base stack of DNA, respectively, was anticipated to create three-dimensional arrays of nanoparticles intermingled with DNA (Figure 2). Such aggregation is known to affect both the longitudinal and the transverse relaxivity of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, and is the basis for responsive particulate MRI contrast agents.35–41 As such, the response of both probes to DNA was expected to be observable not only by luminescence but also by MRI.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the dual responsive magnetolight-switches, Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1) and Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2).

Figure 2.

Principle of action of the dual responsive magnetolight-switches. Intercalation of the Phen and dppz ligands in DNA causes the europium and ruthenium complex to turn off and on, respectively. Intercalation also causes aggregation of the iron oxide nanoparticles which decreases both their r1 and r2.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and characterization of the magnetoluminescent assemblies

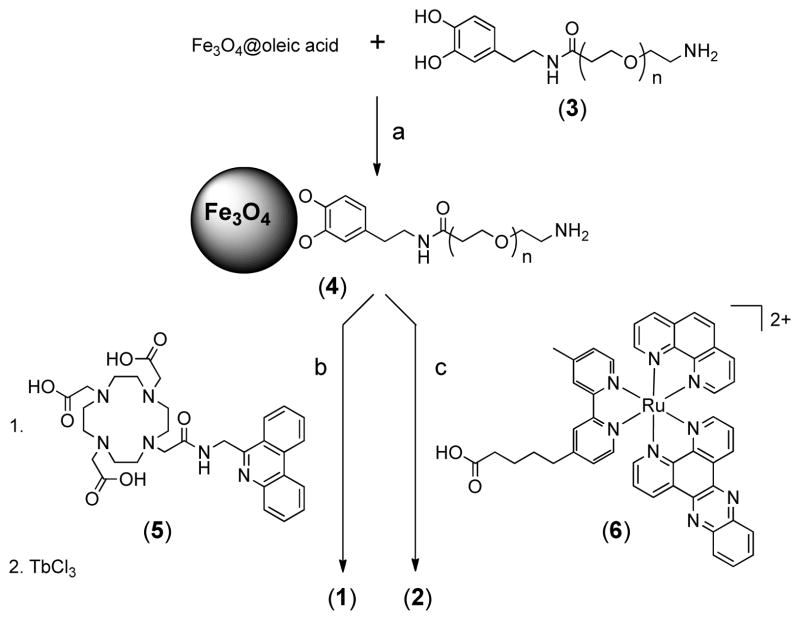

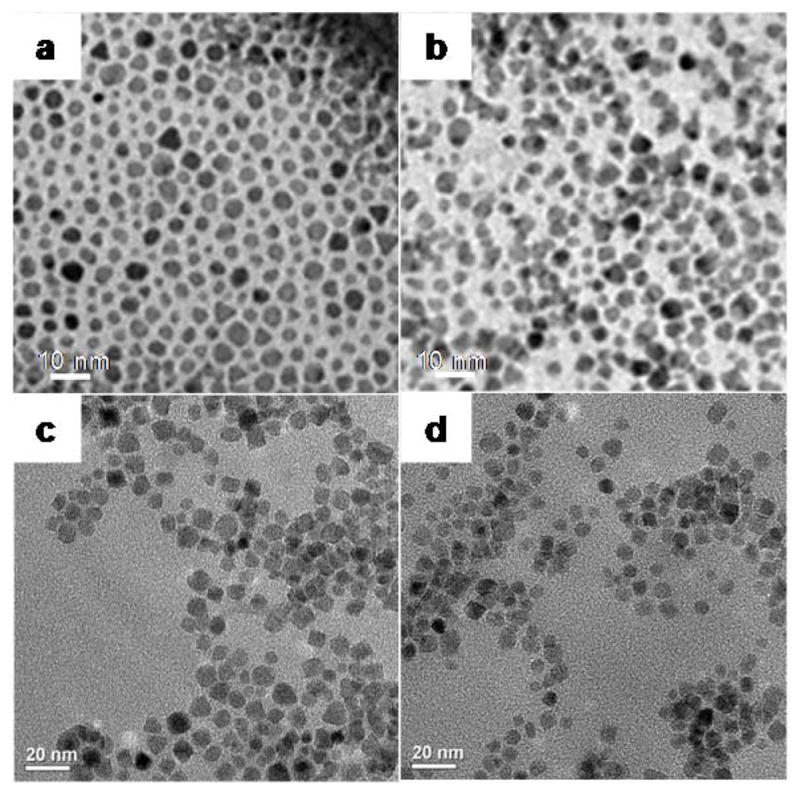

The two bimetallic nanocomposites were synthesized from a common intermediate, Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-NH2 (4, Scheme 1), which was obtained by re-functionalizing oleic acid coated magnetite nanoparticles with a catechol-terminated polymer according to a biphasic procedure previously reported.19 The peripheral amines of the nanoparticles were then conjugated either to the macrocyclic ligand DOTA-Phen (5) or to the acid-functionalized Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) using standard amide coupling conditions. The syntheses of Fe3O4@oleic acid nanoparticles,42 the catechol-terminated polymer Dop-PEG-NH2 (3),41 the macrocyclic ligand DOTA-Phen (5), 20,25 and the ruthenium intercalating complex, Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (6) 26,43–45 were performed as previously reported. The iron/lanthanide composite is then obtained by heating the DOTA-Phen coated nanoparticles at 40°C with an excess of EuCl3 at neutral pH. The efficacy of the conjugation was established by ICP-MS in terms of Fe:Eu and Fe:Ru ratio, respectively, and by infrared spectroscopy (Figure 3). TEM (Figure 4) confirmed that the size of the nanoparticles was not affected by the reactions. The Fe:Eu and Fe:Ru assemblies were 17.8 ± 1.4 nm and 20.4 ± 1.6 nm in diameter, respectively. This size was selected as it is the optimum size to achieve maximum longitudinal and transverse relaxivities.46

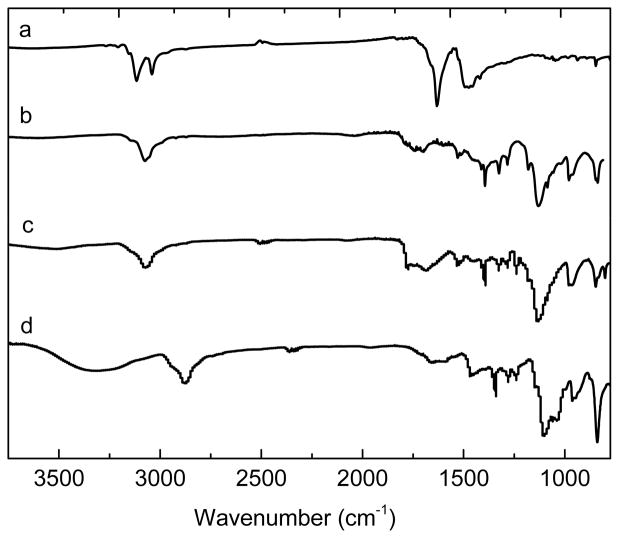

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1) and Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2).a

aReagents and conditions: a) hexanes / H2O pH 14, RT, 12 h; b) i. DOTA-Phen, EDC, NHS, NEt3, RT, 8 h; ii. EuCl3 H2O, pH 7, 40 °C, 24 h; c) EDC, NHS, NEt3, RT, 15 h.

Figure 3.

Infrared spectra of a) Fe3O4@oleic acid, b) Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-NH2 (4), c) Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1) and d) and Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2).

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of a) MION@OA, b) MION@DPEGNH2, c) Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1), and d) Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2).

Although it should be assumed that not all peripheral amines on the nanoparticles have been conjugated to the intercalators, the high Fe:Eu ratio of 67:60 suggests a very effective reaction with the DOTA-Phen ligand. On the other hand, the low Fe:Ru ratio of 87:1 highlights a much less efficient conjugation with the bulkier ruthenium complex which, unfortunately, we were not able to improve by varying reaction conditions. The third advantage of this synthetic approach concerns the Fe/Eu nanoparticles. This core-shell assembly is composed of two hard metals. Our initial attempts to directly functionalize the nanoparticles with the polymer-lanthanide complex, Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTA-Phen, were unsuccessful. The high affinity of the catechol anchor for the lanthanides prevented efficient functionalization of the iron oxide crystals.19 Predictably, direct conjugation of the europium complex, Eu-DOTA-Phen to the amine coated nanoparticles, Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-NH2 also failed; the carboxylate arms of the macrocycle are unreactive when coordinated to the lanthanide ion. The three-step synthesis of the Fe/Eu nanocomposite described above was the highest yielding synthetic route.

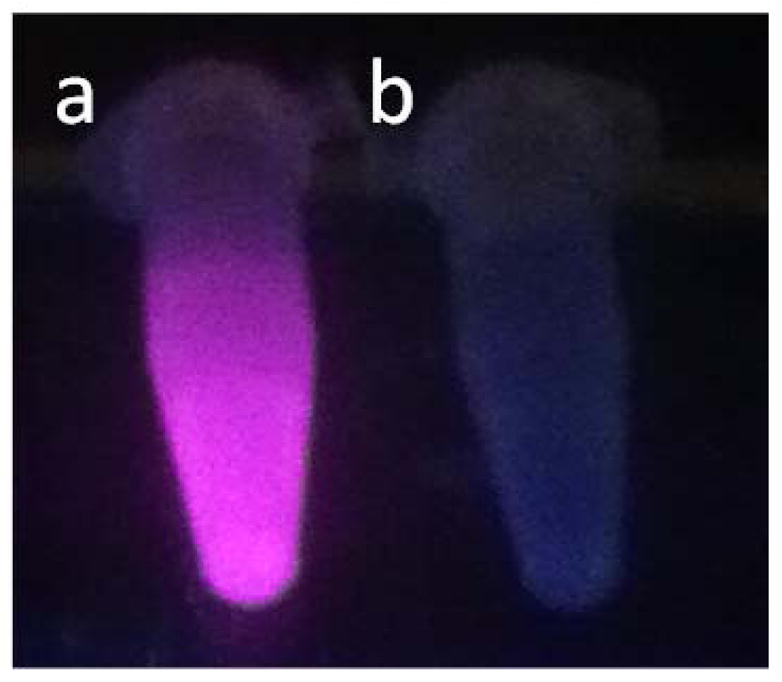

Light switch response

Both the europium and ruthenium coated nanoparticles were designed to behave as luminescent light-switches for DNA detection, albeit with opposite responses. The phenanthridine antenna of the europium complex is known intercalate in dsDNA.21–24 This intercalation quenches both the fluorescence of the antenna and the phosphorescence of the lanthanide. Our group and Parker’s have previously demonstrated that this quenching likely occurs via photoelectron transfer from the purine base guanosine and to a lesser extent adenosine to the phenanthridine antenna.21–24 As predicted, addition of CT DNA or any dsDNA oligonucleotide to the Fe/Eu nanocomposites efficiently quenches lanthanide-centered time-gated luminescence (Figures 5). This quenching is more pronounced at lower excitation wavelengths where PeT is favored: 99 % of the phosphorescence is quenched upon excitation at 254 nm, whereas only 35% is quenched with λexcitation = 347 nm (Figure 6). Advantageously, at the short wavelength of widespread portable UV lamps, the substantial quenching is readily observable with the naked eye (Figure 7). The ruthenium analog, Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2), on the other hand, was designed as a turn-on magnetolight-switch (Figure 8). Unfortunately, poor conjugation of the ruthenium complex on the nanoparticles led to mediocre turn-on activity upon addition of calf-thymus DNA, although it is still noticeable with the naked eye (Figure 9). Notably, the response observed upon intercalation in dsDNA is comparable to that reported by Barton for the parent Ru(bpy)2(dppz).26 Notably, the light switch responses observed for Eu-DOTA-Phen (turn-off) and Ru(bpy)2(dppz) (turn-on) occurs only upon intercalation in double stranded DNA. Mere interactions with single stranded oligonucleotides are not sufficient to yield the same light-switch response. Compared to double stranded DNA, addition of single stranded DNA at the same concentration of base pair does not noticeably impact the luminescence of either Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) or Eu-DOTA-Phen. Note that ssDNA can quench Eu-DOTA-Phen’s luminescence, but only at concentrations that are substantially higher than that needed with dsDNA: i.e. > 20 mM bases for ssDNA versus 50 μM for dsDNA.

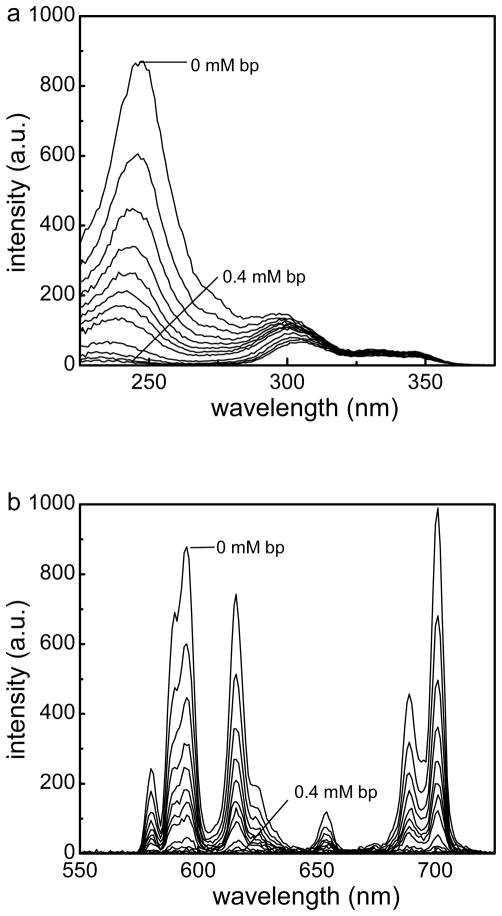

Figure 5.

(a) Time-gated excitation spectra and (b) time-gated emission spectra of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1) upon addition of increasing concentrations of CT DNA. Experimental conditions: PBS, pH 7.4, [Fe]total = 11 μM, [Eu]total = 9.8 μM, T = 20 °C, time delay = 0.1 ms, (a) λemission = 615 nm, (b) λexcitation = 254 nm.

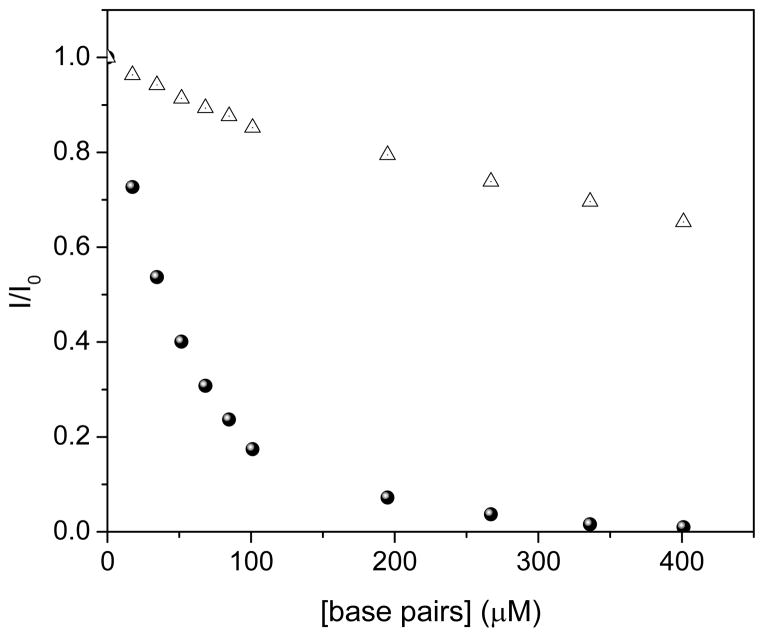

Figure 6.

Decrease in time-gated luminescence intensity of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1) upon addition of CT DNA base pairs upon excitation a λexcitation = 254 nm (filled circles) and 347 nm (open triangles). Experimental conditions: PBS, pH 7.4, [Fe]total = 11 μM, [Eu]total = 9.8 μM, T = 20 °C, time delay = 0.1 ms, integrated emission between λ = 550 nm – 750 nm.

Figure 7.

Luminescence of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1) upon excitation with a portable UV lamp in the absence (a) and presence (b) of CT DNA. Experimental conditions: PBS, pH 7.4, T = 20 °C, λexcitation = 254 nm.

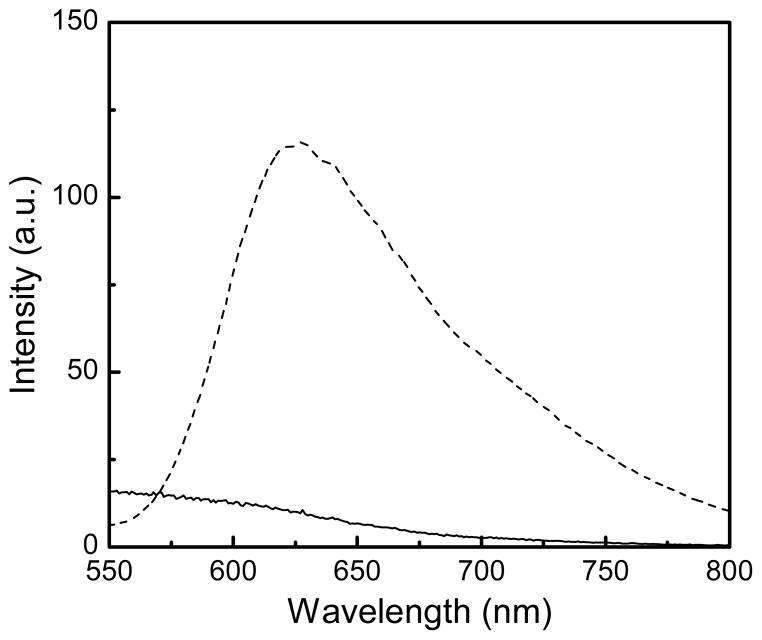

Figure 8.

Luminescence of Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) in the absence (solid line) and presence (dotted line) of CT DNA. Experimental conditions: PBS, pH 7.4, λexcitation = 482 nm, T = 20 °C.

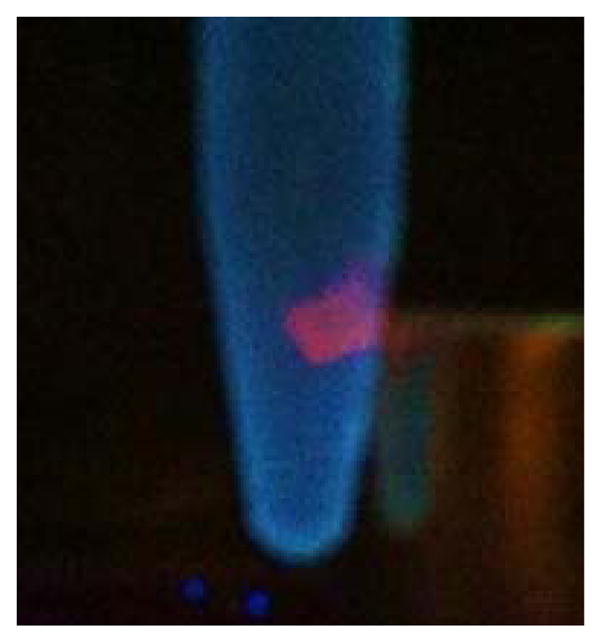

Figure 9.

Luminescence of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) in the presence of CT DNA upon excitation with a portable UV lamp. The (2) • DNA cluster is readily and reversibly separated with a rare earth magnet. Experimental conditions: PBS/ethanol, pH 7.4, λexcitation = 254 nm, T = 20 °C.

Relaxivity response

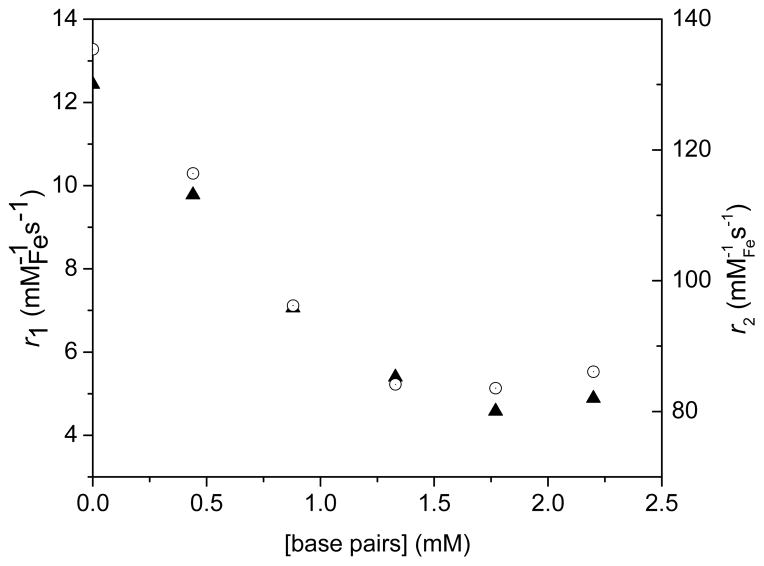

Intercalation of the phenanthridine (Phen) or dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (dppz) ligands in dsDNA results in three-dimensional networks of nanoparticles intertwined with DNA (Figure 2). The formation of this network affects both their longitudinal (r1) and transverse (r2) relaxivities. In terms of longitudinal relaxivity, addition of DNA to the Fe/Eu (1) and Fe/Ru (2) nanocomposites decreases r1 by 33 % (Figure 10) and 61% (Figure 11), respectively. This result is consistent with prior observations from our group41 and others47–48 and is likely due to the formation of two pools of water that exchange significantly slower than the NMR time scale. The water trapped within the network relaxes rapidly due to its proximity to multiple iron oxide nanoparticles. This fast-relaxing water pool is, however, negligible compared to the bulk water that resides outside of the array and which is little affected by the DNA/nanoparticle cluster. Since the water between the two pools exchange slowly, the overall result is a decrease in r1.

Figure 10.

Decrease in longitudinal (r1, filled triangles) and transverse (r2, open circles) relaxivities of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAmPhen (1) upon addition of CT DNA. Experimental conditions: PBS, pH 7.4, 1.5 T (60 MHz), T = 37 °C.

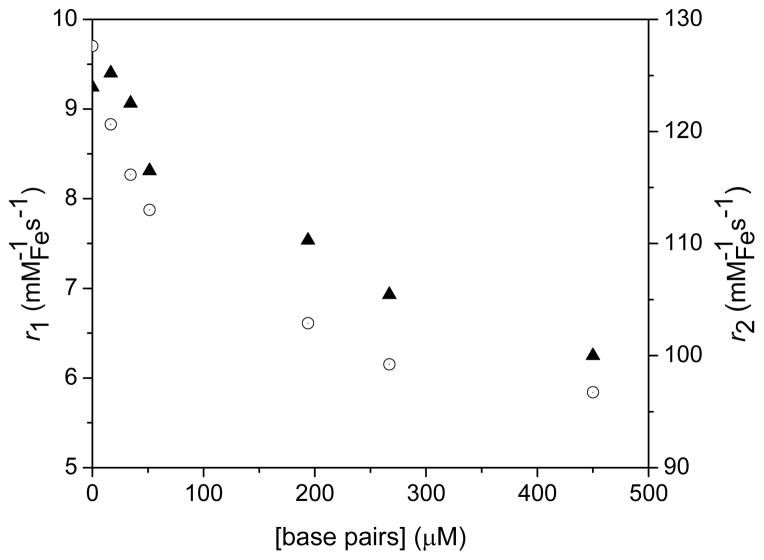

Figure 11.

Decrease in longitudinal (r1, filled triangles) and transverse (r2, open circles) relaxivities of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2) upon addition of CT DNA. Experimental conditions: PBS, pH 7.4, 1.5 T (60 MHz), T = 37°C.

Interestingly, the transverse relaxivity, r2, also decreases upon addition of DNA for both nanocomposites. This observation appears to be contradictory to that of previous responsive particulate contrast agents. It is, however, predictable given the size of the networks formed. Unlike for longitudinal relaxation, the effects observed for transverse relaxivity arise from changes in the global structure of the cluster and the magnetic field surrounding it. As demonstrated by Gillis47–48 and ourselves41, increase in transverse relaxivity with clustering of nanoparticles is only observed for small substrates and, most importantly, small clusters that maintain the motional averaging condition.47–48 In these cases, the cluster itself behaves as a large magnetized sphere whose total magnetic moment increases according to Langevin’s law. The relaxation is governed by the outer-sphere relaxation theory and is characterized by a long correlation time. In our case, however, the long length of CT DNA leads immediately to the formation of very large nanoparticle/DNA clusters. The motional averaging condition breaks down; r2 is instead governed by the static dephasing regime. The translational diffusion time of a proton across the cluster is slowed enough such that its motion, relative to the cluster, is static. Consequently, as the concentration of DNA increases, r2 decreases further with increasing cluster size. Note that the relaxivities of the “bare” nanoparticles which are not functionalized with either metallointercalators, Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-NH2 (4), actually increases slightly upon addition of dsDNA. This response is opposite to that observed when the nanoparticles are coated with metallointercalators thereby supporting our assertion that the decrease in relaxivities observed for the magnetolight-switches (1) and (2) result from intercalation of the metal complex in dsDNA.

Catch-and-release of DNA

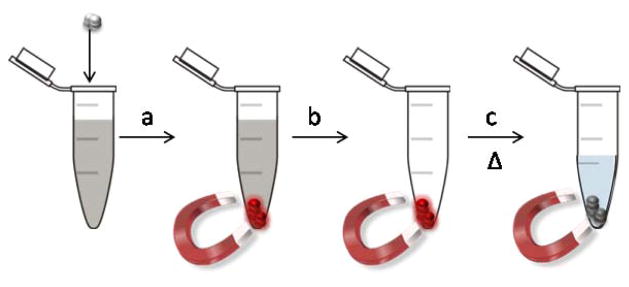

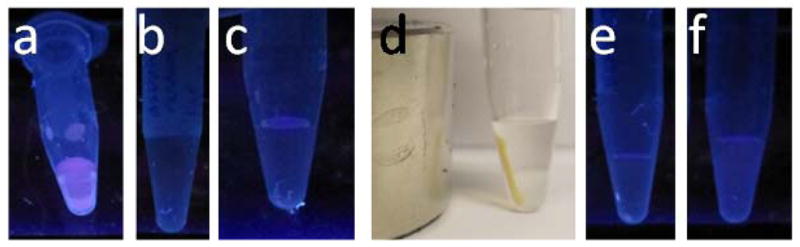

The combination of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with light-switch metallointercalators that bind reversibly to dsDNA opens the intriguing possibility of using the nanocomposites for catch-and-release separation and purification of DNA (Figure 12). Addition of either (1) or (2) to a mixture containing DNA aggregates the polynucleotide with the nanoparticles. The presence of the DNA is at first monitored from the turn-on or turn-off light-switch behavior of the metallointercalator upon UV excitation. For instance, Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTA-Phen is brightly luminescent in water (Figure 13 a). Addition of a dispersion of these nanoparticles to a buffered solution containing dsDNA quenches the lanthanide luminescence (Figure 13 b and c). In this case, nanoparticles were added until some luminescence reappeared so as to ensure that all DNA was caught. At this point, the DNA/nanocomposite clusters can readily be separated from the rest of the mixture with a small rare-earth magnet (Figure 13 d). Note that in the case of the ruthenium functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles (2) this is best observed under UV (Figure 9). At this point, the supernatant which does not contain DNA can be readily pipetted off. The nanoparticles/DNA clusters were re-dispersed in water and heated past the oligonucleotide melting point to release thethe DNA. Note that, unfortunately, the catecholamide linker used to anchor the pegylated metallointercalators is not stable enough at high temperature, such that the Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTA-Phen was released with the DNA. Although the iron oxide nanoparticles could readily be removed magnetically, DNA could only be obtained with the metallointercalators. We are currently investigating more stable anchor to alleviate this problem and increase the efficiency of catch-and-release purification.

Figure 12.

Catch-and-release purification of DNA with (2): a) the nanoparticles are added to a mixture containing DNA; upon intercalation in DNA, the luminescence of the nanoparticles is switched on. b) The clusters of nanoparticles with DNA are magnetically separated from the rest of the mixture. Addition of PBS buffer and gentle heating to 80 °C releases the DNA from the nanoparticles, the unbound nanoparticles are then separated magnetically from the hot suspension.

Figure 13.

a) A dispersion of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTA-Phen in water is luminescent, while b) a solution of dsDNA in PBS buffer is not. c) Addition of the magnetoluminescent nanoparticles to DNA result in extended nucleotide/nanoparticle networks which are no longer luminescent but d) can be readily separated from the rest of the aqueous solution with a magnet. Heating the nanoparticles in water releases both the DNA and the metallointercalators such that neither the nanoparticles redispersed in water (e) nor the supernatant redisolved in water (f) are luminescent.

CONCLUSION

Iron oxide nanoparticles functionalized with light-switch DNA metallointercalators behave as efficient probes with dual response by both luminescence and relaxivity. The luminescence response is a function of the metallointercalator: Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) function as a turn-on light switch upon intercalation in the DNA helix, whereas the lanthanide complex, Eu-DOTA-Phen behaves as an efficient turn-off switch. The response of either intercalator is not affected by the iron oxide nanoparticle. Intercalation of the metal complexes in the DNA helix creates three-dimensional clusters that affect both the longitudinal and transverse relaxivities of the assembly. Regardless of the metallointercalator coating, co-clustering with DNA results in a decrease of both r1 and r2. These decreases are due to the slow exchange of the water molecules trapped inside the cluster with outside bulk solvent and to the very slow translational diffusion time of protons across the cluster, such that the nanoparticles stay in a static dephasing regime. The combination of the two responses and the reversibility in the intercalation opens the possibility to use the magnetoplasmonic light-switches for catch-and-release purification of DNA.

METHODS

General considerations

Unless otherwise noted, starting materials were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Water was distilled and further purified by a Millipore cartridge system (resistivity 18 MΩ). 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 300 at 300 MHz and 75 MHz or on a Varian 500 at 500 MHz and 125 MHz, respectively at the LeClaire-Dow Characterization Facility of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Minnesota. The solvent residual peak was used as the internal reference. Data for 1H NMR as reported as follows: chemical shift (δ, ppm), multiplicity (s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet, m, multiplet), integration, coupling constants (Hz). Data for 13C NMR are reported as chemical shifts (δ, ppm). Mass spectra (LR = low resolution, ESI MS = electrospray ionization mass spectrometry) were recorded on a Bruker BioTOF II at the Waters Center for Innovation in Mass Spectrometry of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Minnesota. TEM images were collected on a JOEL JEM1210, FEI Tecnai T12, or on a JOEL 1200EXII at 120 kV. Relaxivities were measured at 37 °C and 1.5 T (60 MHz) on a Bruker Minispec mq60. The hydrodynamic size of the particles and aggregates were measured by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) with a 90Plus/BI-MAS particle size analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation). Elemental analyses were performed by inductively-coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP OES) on a Thermo Scientific iCAP 6500 duo optical emission spectrometer by the Department of Geology at the University of Minnesota. Solid state infrared spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet 6700 FTIR using an ATR adapter. Data was collected between 700 cm−1 and 3700 cm−1. UV-visible spectra were measured with a Varian Cary 100 Bio Spectrophotometer at T = 20°C. Data was collected between 200 nm and 800 nm using a quartz cell with a path length of 10 mm. Luminescence data were recorded on a Varian Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer using a quartz cell with a path length of 10 mm, excitation slit width of 10 nm, emission slit width of 5 nm at T = 20°C.

Relaxivity

Longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times of the nanoparticles in mQ water were measured on a Bruker Minispec mq60 NMR Analyzer at 60 MHz and 37°C according to the inverse recovery sequence and the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill sequence, respectively. The total concentration of iron of each sample was determined by the equation below. Briefly, 5 μL of each probe was suspended in 200 μL HNO3 (aq) and 100 μL mQ water. Each sample was heated at 100°C overnight, after which T1 of each solution was measured. The resulting concentration of iron was calculated from a calibration plot obtained from standard solutions of FeCl3 in 2:1 HNO3:mQ water calibrated by ICP OES. For each probe, the longitudinal (r1) and transverse (r2) relaxivities were fitted to the following equation.

where i = 1,2

Fe3O4@oleic acid

Oleic acid functionalized magnetite nanoparticles were synthesized according to the procedure reported by Sun et al.42 Nanoparticles were characterized by TEM, DLS, powder XRD and IR.

Dop-PEG-NH2 (3)

The amine terminated poly(ethylene glycol) was synthesized as previously reported.41 Successful synthesis was established by 1H NMR and LR ESI MS.

Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-NH2 (4)

The magnetite nanoparticles were refunctionalized with the catechol-terminated polymer, Dop-PEG-NH2 (3) according to a biphasic procedure previously reported by our group.19 Briefly, a dispersion of Fe3O4@oleic acid in hexane was stirred vigorously with a solution of the poly(ethylene glycol) (3) in mQ water:THF (2:1) at pH 14 for 2 h at 40°C and 12 h at room temperature.The aqueous dispersion was filtered through a microfilterfuge (pore size = 0.6 μm) to remove any clustered nanoparticles. The filtrate was lyophilized, resuspended in mQ water and stored at room temperature as an aqueous dispersion. Successful refunctionalization was established by IR (see Figure 3). Ligand exchange is facilitated by the significantly higher binding affinity of iron for catecholate versus carboxylate. This procedure advantageously minimizes aggregation during refunctionalization while maintaining the magnetism of the metallic core.19

DOTAm-Phen (5)

The macrocylic polyaminocarboxylate ligand was synthesized as previously reported.20,25 Successful synthesis was established by 1H NMR, 13C NMR and LR ESI MS.

Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAm-Phen (1)

The macrocycle DOTAm-Phen (5) (5.0 mg, 8.4 μmol) was dissolved in mQ water (1 mL). N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DDC, 5.0 mg, 24μmol) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 3.0 mg, 26 μmol) were added to the reaction mixture. After stirring for 2 h at room temperature, an aqueous solution of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-NH2 (4, 200 μL, 8.6 mMFe, 1.7 μmolFe) and triethylamine (5 μL, 67 μmol) were added to the reaction mixture which was stirred for an additional 7 h at room temperature. Following the addition of aqueous EuCl3 (50 μL, 40 mM, 2.0 μmol), the pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 7 and further stirred at 40°C for 60 h. The nanoparticles were filtered with a 10kDa MW cutoff filter (Amicon) to remove any unreacted macrocycle and europium. The supernantant was resuspended in mQ water (1.0 mL) and filtered through a 10kDa MW filter again. This last step was repeated thrice. The resulting nanoparticles were resuspended in mQ water. The resulting aqueous dispersion of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Eu-DOTAm-Phen (1) was stored at room temperature. Successful functionalization was assessed by IR and IECP-OES. Elemental analysis (ICP-AES) indicated a ratio of Fe:Eu of 67: 60.

Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (6)

The ruthenium intercalator was synthesized as previously reported26,43–45 with successful synthesis established by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, LR ESI MS and UV/visible spectroscopy.

Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2)

1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC, 1 mg, 6 μmol) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 2 mg, 17 μmol) were added to an aqueous solution of the ruthenium complex Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (6, 1 mg, 0.5 μmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, after which an aqueous solution of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-NH2 (4) was added. The reaction mixture was further stirred at room temperature for 15 h. The nanoparticles were filter with a 10 kDa MW cutoff filter (Amicon) to remove any unreacted macrocycle and europium. The supernantant was resuspended in mQ water (1.0 mL) and filtered through a 10 kDa MW filter again. This last step was repeated thrice. The resulting nanoparticles were resuspended in mQ water and filtered through a microfilterfuge (pore size 0.6 μm) to remove any aggregated nanoparticles. The resulting aqueous dispersion of Fe3O4@Dop-PEG-Ru(bpy′)(phen)(dppz) (2) was stored at room temperature. Successful functionalization was assessed by IR and ICP-OES. Elemental analysis indicated a ratio of Fe:Ru of 87:1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partially by the MRSEC Program of the National Science Foundation (DMR-0819885). Part of this work was carried out in the College of Science and Engineering Characterization Facility, University of Minnesota, which has received capital equipment funding from the NSF through the MRSEC, ERC and MRI programs. EDS gratefully acknowledges partial support from the NIH – Chemical Biology Interface Training Grant (GM 08700). We thank A. Massari and B. Jones for obtaining the IR spectra, and K. Hurley for the TEM images.

References

- 1.Gandhi S, Venkatesh S, Sharma U, Jagannathan NR, Sethuraman S, Krishnan UM. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:15698. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cha EJ, Jang ES, Sun IC, Lee IJ, Ko JH, Kim YI, Kwon IC, Kim K, Ahn CH. J Controlled Release. 2011;155:152. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benyettou F, Lalatonne Y, Chebbi I, Benedetto MD, Serfaty JM, Lecouvey M, Motte L. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:10020. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02034f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunzmann A, Andersson B, Thurnherr T, Krug H, Scheynius A, Fadeel B. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 2011;1810:361. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunzmann A, Andersson B, Vogt C, Feliu N, Ye F, Gabrielsson S, Toprak MS, Buerki-Thurnherr T, Laurent S, Vahter M, Krug H, Muhammed M, Scheynius A, Fadeel B. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;253:81. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veiseh O, Sun C, Fang C, Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Kievit F, Du K, Pullar B, Lee D, Ellenbogen RG, Olson J, Zhang M. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6200. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan S, Huang J, Guo M, Zhang H, Cao Y, Yan H, Liu K. J Biomed Mat Res A. 2007;80A:946. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kell AJ, Barnes ML, Jakubek ZJ, Simard B. J Phys Chem C. 115:18412. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smolensky ED, Neary MC, Zhou Y, Berquo TS, Pierre VC. Chem Commun. 2011;47:2149. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03746j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung KCF, Xuan SH, Zhu XM, Wang DW, Chak CP, Lee SF, Ho WKW, Chung BCT. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:1911. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15213k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xi PX, Cheng K, Sun XL, Zeng ZZ, Sun SH. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:11464. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li MJ, Chen Z, Yam VWW, Zu Y. ACS Nano. 2008;2:905. doi: 10.1021/nn800123w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang LH, Liu BF, Dong SJ. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:10448. doi: 10.1021/jp0734427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou JG, Gan N, Hu FT, Zheng L, Cao YT, Li TH. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2011;6:2845. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolensky ED, Zhou Y, Pierre VC. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2012:2141. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xi PX, Cheng K, Sun XL, Zeng ZZ, Sun SH. Chem Commun. 2012;48:2952. doi: 10.1039/c2cc18122c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kell AJ, Barnes ML, Jakubek ZJ, Simard B. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:18412. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weitz EA, Lewandowski C, Smolensky ED, Marjanska M, Pierre VC. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smolensky ED, Park HYE, Berquó TS, Pierre VC. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6:189. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weitz EA, Chang JY, Rosenfield AH, Pierre VC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16099. doi: 10.1021/ja304373u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bobba G, Dickins RS, Kean SD, Mathieu CE, Parker D, Peacock RD, Siligardi G, Smith MJ, Gareth Williams JA, Geraldes CFGC. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 2001:1729. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bobba G, Kean SD, Parker D, Beeby A, Baker G. Journal of the Chemical Society-Perkin Transactions 2. 2001:1738. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bobba G, Frias JC, Parker D. Chem Commun. 2002:890. doi: 10.1039/b201451n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bobba G, Bretonniere Y, Frias JC, Parker D. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2003;1:1870. doi: 10.1039/b303085g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weitz EA, Chang JY, Rosenfield AH, Morrow EA, Pierre VC. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman AE, Chambron JC, Sauvage JP, Turro NJ, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4960. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman AE, Kumar CV, Turro NJ, Barton JK. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartshorn RM, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5919. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins Y, Friedman AE, Turro NJ, Barton JK. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10809. doi: 10.1021/bi00159a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dupureur CM, Barton JK. Inorg Chem. 1997;36:33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson EJC, Hu D, Hormann A, Jonkman AM, Arkin MR, Stemp EDA, Barton JK, Barbara PF. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11458. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmlin RE, Stemp EDA, Barton JK. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:29. doi: 10.1021/ic970869r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim MH, Song H, Olmon ED, Dervan EE, Barton JK. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:5392. doi: 10.1021/ic900407n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song H, Kaiser JT, Barton JK. Nat Chem. 2012;4:615. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogdanov A, Jr, Matuszewski L, Bremer C, Petrovsky A, Weissleder R. Molecular imaging. 2002;1:16. doi: 10.1162/15353500200200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Josephson L, Perez JM, Weissleder R. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:3204. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010903)40:17<3204::AID-ANIE3204>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez JM, Josephson L, O’Loughlin T, Hogemann D, Weissleder R. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:816. doi: 10.1038/nbt720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez JM, O’Loughin T, Simeone FJ, Weissleder R, Josephson L. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2856. doi: 10.1021/ja017773n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez JM, Simeone FJ, Saeki Y, Josephson L, Weissleder R. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10192. doi: 10.1021/ja036409g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao M, Josephson L, Tang Y, Weissleder R. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:1375. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smolensky ED, Marjanska M, Pierre VC. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8039. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30416c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun S, Zeng H, Robinson DB, Raoux S, Rice PM, Wang SX, Li G. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;126:273. doi: 10.1021/ja0380852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sitlani A, Long EC, Pyle AM, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:2303. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holmlin RE, Yao JA, Barton JK. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:174. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmlin RE, Dandliker PJ, Barton JK. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:1122. doi: 10.1021/bc9900791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smolensky ED, Park HYE, Zhou Y, Rolla GA, Marjanska M, Botta M, Pierre VC. J Mat Chem B. 2013;1:2818–2828. doi: 10.1039/C3TB00369H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roch A, Gillis P, Ouakssim A, Muller RN. J Magn Magn Mater. 1999;201:77. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roch A, Muller RN, Gillis P. J Chem Phys. 1999;110:5403. [Google Scholar]