Abstract

Objective

To assess the effect of initial visit with a specialist on disease understanding in women with pelvic floor disorders.

Methods

Women with referrals or chief complaints suggestive of urinary incontinence (UI) or pelvic organ prolapse (POP) were recruited from an academic urology clinic. Patients completed a Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) and scripted interview sessions before and after the physician encounter. Physician treatment plans were standardized based on diagnosis and were explained using models. Interview transcripts were analyzed using qualitative grounded theory methodology.

Results

Twenty women with pelvic floor disorders (UI or POP) were recruited and enrolled in this pilot study. The mean age was 60.5 years (range 31–87 years) and the majority of women were Caucasian with a college degree or beyond. TOFHLA scores indicated adequate to high levels of health literacy. Preliminary themes before and after the physician encounter were extracted from interviews, and two main concepts emerged: 1) After the initial physician visit, knowledge of their diagnosis and the ability to treat their symptoms relieved patient concerns related to misunderstandings of the severity of their disease 2) Patients tended to focus on treatment and had difficulty grasping certain diagnostic terms. This resulted in good understanding of treatment plans despite an inconsistent understanding of diagnosis.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrated a significant effect of the initial physician visit on patient understanding of her pelvic floor disorder. Despite the variation in diagnostic recall after the physician encounter, patients had good understanding of treatment plans. This served to increase perceived control and adequately relieve patient fears.

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic floor disorders considerably impair the quality of life for many women. They include pelvic organ prolaspe (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI), and are defined by the International Continence Society.1 POP is the descent of the anterior wall, posterior wall, or apex of the vagina. Urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine, and may be classified into stress urinary incontinence (SUI) which is leakage on effort, exertion, sneeze or cough; Urge urinary incontinence (UUI) which is also referred to as overactive bladder (OAB); or mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) which includes both SUI and UUI.1,2

Population projections using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and National Health Nutrition Examination Survey have estimated that the incidence of women with at least one pelvic floor disorder will nearly double by the year 2050 from 28.1 million to 43.8 million.3 These extrapolations predict that in this time, the incidence of women with POP will increase by 46% and UI by 55%. Moreover, approximately 11% of women will have to undergo surgery for POP or UI by the age of 80.4,5 Of these, 29% will require re-operation for recurrence of symptoms.4 It is estimated that from 2010 to 2050, the total number of women undergoing surgery for SUI and POP will increase by 47.2% and 48.2%, respectively.6

Currently, there is a paucity of data regarding the concerns of women with pelvic floor disorders. We previously conducted focus groups of women with OAB to better comprehend their experiences with OAB and their level of understanding. We found that women lacked an understanding about the cause of OAB, its chronicity, and the rationale for various diagnostic tests. This resulted in dissatisfaction with care.7 Disease understanding has been shown to correlate to health literacy, which is defined by the American Medical Association Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy as “the ability to perform basic reading and numerical tasks required to function in the health care environment” and may be determined by the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA).8 We conducted an initial pilot study comparing health literacy and disease understanding in women with pelvic floor disorders. We found that, despite high health literacy levels, 30% of patients with POP had poor recall and understanding of their disease and treatment plan.9 The purpose of this pilot study was to better assess these gaps in disease understanding by measuring the effect of the initial visit with a specialist on patient understanding of diagnosis and treatment plan.

METHODS

Patient Recruitment

We obtained approval from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) institutional review board, and recruited patients from a single female urology specialty clinic within the UCLA healthcare system. Women eligible for our study included new patients with referrals or chief complaints suggestive of any types of urinary incontinence (UI) or pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Potential subjects were excluded if they did not speak English, were younger than 21 years of age, or had dementia prohibiting effective interviewing.

Files of all new female patients were screened on patient arrival to the office for referrals or chief complaints of stress urinary incontinence (SUI), overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms, mixed urinary incontinence (MUI), and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) of any compartment at any stage. Patients with chief complaints consistent with POP or UI were recruited at their first office visit and informed consent was obtained. Diagnoses were confirmed by the physician based on history and physical. Patients were excluded if once examined, they were determined to not have a diagnosis of UI or POP. Patients participated in a health literacy assessment and interview session with a trained female research assistant before and after their physician encounter (Appendix 1). Participants were provided with a small honorarium for their time.

Health Literacy Assessment

To assess the health literacy of participants, they were asked to complete the long form (22-minute) of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) under the supervision of a trained female assistant. The TOFHLA consisted of two timed sections: numeracy (10 minutes) and reading comprehension (12 minutes).10 The TOFHLA scores were then graded and scored on a 100-point scale, with scores above 75 indicating adequate health literacy.

Patient Interviews

After completion of the health literacy test and prior to initial physician visit, a trained female assistant used pre-scripted questions to interview patients. The interviewer was a research coordinator with medical knowledge and training in qualitative theory methodology. The questions included the following: “Please explain to me why you are here to see the doctor today and what you think your diagnosis might be.” After the physician visit, the female assistant interviewed patients again using pre-scripted questions: “Can you please tell me what the doctor told you your diagnosis was today?” and “What treatment options did your doctor offer you today?” All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Initial Physician Visit

Physician treatment plans were based on patient diagnosis and were consistent with current standars of care. All patients were counseled on their diagnosis and treatment plan with the use of pelvic models. During physical exam, all patients were also tested on pelvic muscle strength and given a demonstration on how to perform pelvic floor exercises.

Qualitative Analysis

The interview transcripts were analyzed using qualitative grounded theory methodology as outlined by Charmaz.11 Unlike quantitative research methodology, qualitative methodology does not test a hypothesis. Instead, it allows the researcher to search for a theory implicit in the data. The researcher identifies key issues by coding and finding categories, which includes initial line-by-line coding of transcripts using key phrases in the patient’s own words. Next, similarly coded phrases are grouped together into preliminary themes. Then, preliminary themes are aggregated to develop categories. Finally, core categories or emergent concepts are derived from these themes. To reduce subjectivity, three individual investigators performed line-by-line coding and derived preliminary themes that were later compared and merged. The investigators included a combination of clinical MDs and PhDs with expertise in female urology and qualitative methodology.

RESULTS

Twenty women with pelvic floor symptoms suggestive of UI (N=16) or POP (N=4) were recruited and enrolled in this study. Mean age was 60.5 years (range 31–87 years) and the majority of women were Caucasian with a college degree or beyond (Table 1). The average TOFHLA score was 93 (range 84–100), indicating high health literacy levels. Qualitative data analysis was utilized to extract key phrases that emerged from patient interviews before and after physician encounter. Preliminary themes were extracted during data analysis (Table 2, Table 3), and patients’ level of understanding was compared before and after the office visit (Table 4). These preliminary themes fell into two main categories: 1) After the initial physician visit, patients’ fears were relieved by regaining control and understanding of their disease, 2) Patients tended to focus on treatment and had difficulty grasping diagnostic terms. This resulted in a good understanding of their treatment plan, yet an incomplete understanding of their diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Mean Age (range) | 60.5 (31–87) |

| Average TOFHLA score (range) | 93 (84–100) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 15 |

| Hispanic | 3 |

| African American | 1 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Education Level | |

| College + | 8 |

| Some college | 6 |

| High school | 4 |

| Declined to state | 2 |

Table 2.

Preliminary themes and representative quotes before physician encounter

| Preliminary Themes | Representative Patient Quotes | Physician’s Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Focus on bladder as the cause | Weak bladder. | SUI |

| Leaky bladder. | OAB | |

| I have bladder problems. | MUI | |

| The bladder is sagging. | MUI | |

| I think she's going to find my bladder is a little worn. | Prolapse (cystocele) | |

| Felt like my bladder was in the wrong place. | Prolapse (cystocele) | |

| Incorrect diagnosis by other healthcare provider | I was told that I have severe prolapse. | SUI |

| I was told that I have a tear. | SUI | |

| I was told there might be something wrong with the urethra. | OAB | |

| Misconception that their problem is due to aging | Getting old. | OAB |

| My muscles are getting weaker as I age. | MUI | |

| After 48 years my bladder is a little worn. | Prolapse (cystocele) | |

| Feeling of lack of control over problem | I want to prevent wearing depends. | OAB |

| It's a problem beyond my control. | OAB | |

| I have uncontrollable bladder leakage. | OAB | |

| I have no control over it. | MUI | |

| Unsure of cause of symptoms | Probably due to weak muscles due to subcervical hysterectomy. | MUI |

| There's something hanging out of my vagina. | Prolapse (cystocele) |

SUI, Stress Urinary Incontinence; OAB, overactive bladder; MUI, mixed urinary incontinence

Table 3.

Preliminary themes and representative quotes after physician encounter

| Preliminary Themes | Representative Patient Quotes | Physician’s Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Relief because their disorder is not as bad as they feared | The doctor doesn't think it's as severe as the original person I saw. I'm relieved because I don't need surgery. | SUI |

| It's no major biggie, I feel more at ease. | OAB | |

| Surgery would be a final resort. | MUI | |

| I have cystocele and it doesn't seem to be real bad. | Prolapse (cystocele) | |

| The surgery would be minorly intrusive and I can recover pretty quickly, so good news. | Prolapse (cystocele) | |

| Relief because something can be done to gain control or problem | The doctor found problems and can fix them. | SUI |

| The pessary is temporary, I'd rather have the operation. | Prolapse (cystocele) | |

| The surgery would alleviate the feeling of pressure in my vagina. | Prolapse (cystocele) | |

| I feel much better. She put the thing (pessary) in and I can really feel the difference. | Prolapse (apical) | |

| Good understanding of treatment despite incomplete understanding of diagnosis | I don't know what kind of incontinence I have but I'm a good candidate for sling surgery. | SUI |

| I have leakage and I need a sling. | SUI | |

| Umm, I think I have a hormone situation. I have to do Kegels and use estrogen cream. | OAB | |

| I didn't even hear my diagnosis. She gave me Vesicare and Kegel exercises. | OAB | |

| If the medication doesn't work, the sling method would definitely help with the laugh, cough, sneeze urgency. | MUI | |

| I have stress incontinence and laugh, cough, sneeze incontinence. I should restrict fluid intake, do Kegel exercises, and try the medication. | MUI | |

| The vagina is dropping down and the repair would involve attaching something to the sacrum to lift it up. | Prolapse (apical) | |

| I can't remember the diagnosis but she offered me the circular diaphragm thing or surgery. | Prolapse (cystocele) |

SUI, Stress Urinary Incontinence; OAB, overactive bladder; MUI, mixed urinary incontinence

Table 4.

Diagnosis in Patient’s Own Words: Before and After Physician Encounter

| Physician's Diagnosis |

Patient Diagnosis (before) | Patient Diagnosis (after) |

|---|---|---|

| SUI (N=4) | Weak bladder that may require surgery. | Incontinence due to having babies. |

| Severe prolapse, rectocele and cystocele. | The doctor doesn't think the prolapse is as severe as the original person I saw. | |

| I don't know. | My bladder, irritation. | |

| I was told there were two different conditions I could have. One is taking medicine orally and two is having stitches to sew up the tear. | I have leakage. | |

| OAB (N=9) | Urinary incontinence. | Low estrogen. |

| Leaky bladder. | Bad bladder. | |

| Weak muscles, getting old. | Overactive bladder. | |

| I have incontinence. | Urge incontinence. | |

| Something wrong with the urethra. | Overactive bladder. | |

| Chronic irritation of the bladder. | A hormone situation, irritation due to that. | |

| Incontinence, I think. | Incontinence, urge. | |

| Hopefully cystitis; dreadfully cancer. | I didn't even hear it, she was going to order tests. | |

| Bladder leakage. | It sounds like I have overactive bladder. | |

| MUI (N=3) | Incontinence. | Incontinence, it was urgent. |

| Urinary incontinence. | Urinary icontinence, stress and urge incontinence. | |

| Issue with urine leaking. | Two different things. The stress incontinence and the laugh, cough, sneeze incontinence. | |

| Prolapse (N=4) | Incontinence and prolapse in rectocele. | The top of the vagina is dropping down. |

| A slight infection. I have a cystocele. | I have a cystocele and it doesn't seem to be real bad. | |

| Prolapsed uterus. | Stage 1 prolapse. | |

| My primary care physician said it might be the uterus but I suspect it's the bladder. | The uterus is going into the vagina and it's pushing the bladder out. |

SUI, Stress Urinary Incontinence; OAB, overactive bladder; MUI, mixed urinary incontinence

Preliminary themes were generated from key phrases in the patient’s own words. Table 2 provides examples of representative quotes used to exemplify the five preliminary themes from the pre-visit interview. The first preliminary theme identified was a focus on the bladder as the cause of their symptoms. Across all types of UI and in some cases of POP, patients identified their bladders as the causes of their problems (Table 2). The second theme was that healthcare providers gave patients incorrect information. One patient without physical examination findings of POP had been told that she had severe prolapse. The third identified theme was a misconception that their disease was a normal part of aging and therefore something that they must accept. The fourth identified theme was that patients felt an initial lack of control over their problem. Some patients complained of having to wear pads in order to feel protected against leaking, while one patient blatantly stated, “It’s a problem beyond my control.” Finally, patients often had a poor understanding of their pelvic anatomy and the cause of their symptoms.

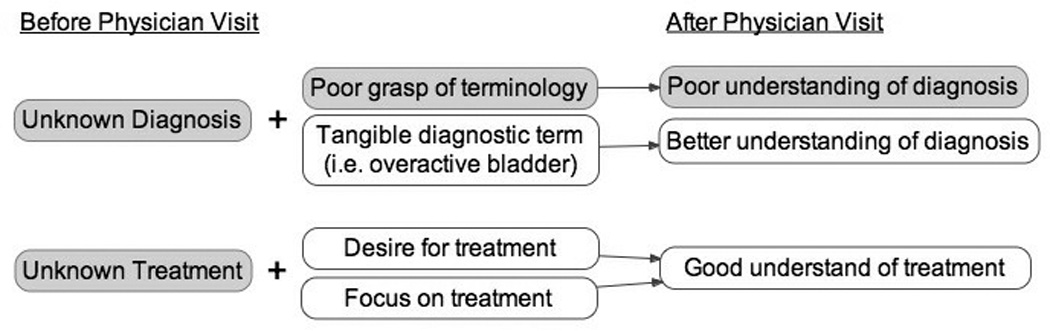

The interview after the initial physician visit yielded three preliminary themes, as seen in Table 3. The first finding was that patients felt relief when they learned that their diagnosis was not as severe as they initially feared. Several patients were thankful to discover they did not have cancer, while others were relieved to learn that their condition did not warrant surgery. The second theme identified was a sense of relief patients felt because they could do something to gain control of their condition. Patients with prolapse expressed a sense of relief that their symptoms would resolve. The last theme identified was that patients had a good understanding of treatment, despite incomplete understanding of their diagnosis. Even patients who could not recall their diagnosis could explain their treatment options. One patient was confused about her diagnosis of mixed urinary incontinence, but understood her treatment and said, “I have stress incontinence and laugh, cough, sneeze incontinence. I should restrict fluid intake, do Kegel exercises, and try the medication.” This lack of understanding of diagnosis is further demonstrated in Table 4, in which the diagnoses in the patients’ own words were assessed before and after the physician visit. When tangible terms such as “overactive bladder” are given, patients had a better recall of their diagnosis.

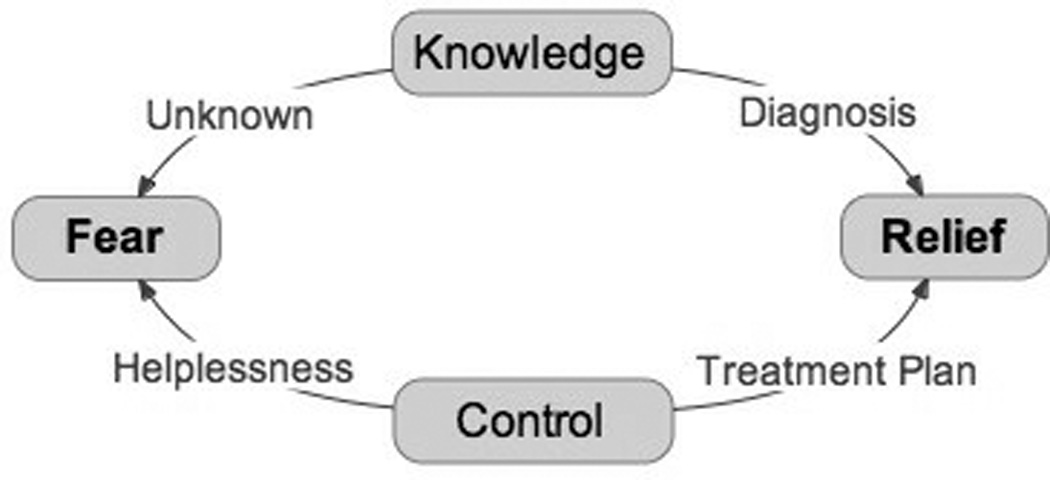

From these preliminary themes, two emergent concepts developed. First, after the initial physician visit, knowledge of their diagnosis and the ability to treat their symptoms relieved patient concerns related to misunderstandings of the severity of their disease (Figure 1). Patients initially had a lack of knowledge of their disease and feared the possibility of an unknown severe diagnosis or the need for surgery. They also felt as though they had a lack of control over their symptoms. In these cases, patients were relieved to find that they did not have a serious illness that mandated surgery. Furthermore, patient concerns were allayed by a treatment plan, which returned to them a sense of control over their condition. Second, patients had a good understanding of their treatment plan, yet an incomplete understanding of their diagnosis. They had the tendency to focus on treatment, rather than diagnosis (Figure 2). Contributing to a poor understanding of diagnosis was that new or abstract concepts, like stress incontinence, were difficult for patients to readily recall. However, coined diagnostic terms such as “overactive bladder” were easier for patients to grasp.

Figure 1.

Emergent concept: Resolution of fear after physician visit due to gain of knowledge and control of condition

Figure 2.

Emergent concept: Focus on treatment and poor understanding of diagnostic terms yielded good understanding of treatment plan despite incomplete understanding of diagnosis

DISCUSSION

Through open-ended interviewing before and after initial physician encounter, we noted a significant effect of the initial visit with a specialist on patient perceptions and disease understanding. The first emergent concept, that patient education caused significant relief after the initial visit, is in accordance with information desired by patients with chronic diseases as described by Holman and Lorig.10 They reported that patients with chronic diseases, such as overactive bladder and urge incontinence, desire different information than patients with acute diseases, such as diagnosis and available treatments, consequences of diagnosis and treatment, and the potential impact on the patient’s future.12 Furthermore, studies in patients with chronic diseases, such as back pain, have shown that patients given supplemental information and education on supporting active management of their condition have significantly greater reductions in worry and fear-avoidance beliefs.13 Similarly, studies in heart failure patients found that patients with high perceived control had better functional status, less anxiety, less depression and better quality of life than patients with low perceived control.14, 15

The second emergent concept was that after their initial office visit, patients had a good understanding of their treatment plan despite incomplete understanding of their diagnosis (Figure 2). We hypothesize that this lack of understanding could be due to one of two reasons. First, patients seemed to focus on treatment because they had a difficult time recalling new or abstract concepts, like stress incontinence. However, tangible or popularly used terms such as “overactive bladder” were easier for patients to grasp (Table 4). Although there are many problems with the term “overactive bladder,” because it encompasses several disease entities and is problematic diagnostically,16 it is one of the few terms patients could readily recall. Secondly, patients may have forgotten their diagnosis because it was less important to them than their need to treat their bothersome symptoms. Patients were able to recall every step of a multifaceted treatment plan despite being unable to correctly name their diagnosis. This finding is in line with previous focus group work in patients with OAB, which revealed a “desperate quest for a cure” among patients.7 Further supporting the hypothesis that patients may be preoccupied with treatment was a qualitative study in patients with end stage renal disease who underwent kidney transplantation. Fisher et al. found that patients had an overwhelming desire to undergo transplantation in order to avoid routine dialysis, and this preoccupation resulted in poor recall of information regarding the negative effects of transplantation.17 Our patients seemed to focus on treating their condition, which resulted in a good understanding of treatment that did not correlate to understanding of their diagnoses.

The use of qualitative methodology is valuable for describing and interpreting patient views and subjective themes that may influence patient perceptions.18 It also provides a means for analyzing data not readily extracted from clinical charts. Furthermore, qualitative research may generate theories that can serve as the basis for future quantitative studies.18 Two topics that would be useful to examine in the future are: 1) Patient expectations for treatment options prior to the visit; 2) Specific obstacles to patient understanding and what strategies were most helpful to overcoming these barriers in communication.

Despite its strengths, qualitative analysis and interview based studies may contain inherent biases. In order to reduce inconsistencies in patient experiences, the physician treatment plans varied with diagnoses, but treatment for each condition was consistent with current standards of care.. All patients received the same explanation of their diagnosis and treatment using pelvic models. A possible study bias may exist in any study where the patients are aware that they are being assessed for recall. However, our findings indicate that despite this potential bias, women still had a poor understanding of their diagnoses. Finally, a repeated criticism of grounded theory methodology is the potential for bias based on individual researcher preconceptions.19 In order to reduce the effects of researcher subjectivity, transcripts were de-identified and independently coded by three separate investigators. The investigators included clinicians and non-clinician researchers, who independently coded transcripts and developed preliminary themes, which were later compared and merged.

We recognize that this pilot study may not be representative of patients as a whole, as our patients were recruited from a single urology clinic where they were referred to a specialist. Therefore, our patients may not represent all women with pelvic floor disorders in the primary care setting. We intend to expand this study to another institution, focusing on a predominantly Hispanic population.

CONCLUSION

The use of grounded theory methodology to analyze interviews before and after the initial physician visit revealed that the physician visit had a significant effect on patients’ perceptions of their pelvic floor disorders. Prior to physician encounter, patients had a poor understanding of both their diagnosis and treatment options, which led to fears regarding severity of diagnosis and lack of control over their condition. After the physician encounter, patients had variable recall of their diagnosis. However, most patients could readily recall a multifaceted treatment plan and had relief of their original concerns due to an increase in perceived control. Regardless of poor diagnostic recall, the relief of initial patient fears and understanding of a treatment plan seems to have adequately addressed the needs of our patients. It is unclear to what extent further elucidation of diagnosis would benefit patient perception or outcome of pelvic floor disorders. This study represents the benefit of grounded theory methodology in understanding the concerns of our patients and their perceived needs in patient care.

Acknowledgments

Funded by a Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award 1 K23 DK080227-01 (JTA), American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Supplement 5K23DK080227-03 (JTA) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:116–126. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.125704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010–2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1278–1283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fialkow MF, Newton KM, Lentz GM, Weiss NS. Lifetime risk of surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:437–440. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Hundley AF, Dieter AA, Myers ER, Sung VW. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:230.e1–230.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anger JT, Nissim HA, Le TX, Smith AL, Lee U, Sarkisian C, Litwin MS, Raz S, Rodriguez LV, Maliski SL. Women’s Experience with Overactive Bladder Symptoms and Treatment: Insight Revealed from Patient Focus Groups. Accepted for publication in Neurourol Urodyn. doi: 10.1002/nau.21004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy American Medical Association. JAMA. 1999;281:552–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anger JT, Nissim HA, Le TX, Smith AL, Lee U, Sarkisian C, Litwin MS, Raz S, Rodriguez LR, Maliski SL. Women’s Experience with Overactive Bladder Symptoms and Treatment: Insight Revealed from Patient Focus Groups. Accepted for publication in Neuro Urol. doi: 10.1002/nau.21004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:437–441. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charmaz K. Discovering chronic illness: using grounded theory. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:1161–1172. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90256-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore E, Von Korff M, Cherkin D, Saunders K, Lorig K. A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral program for enhancing back pain self care in a primary care setting. Pain. 2000;88:145–153. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallas CN, Wray J, Andreou P, Banner NR. Depression and perceptions about heart failure predict quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure. Heart Lung. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.008. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dracup K, Westlake C, Erickson VS, Moser DK, Caldwell ML, Hamilton MA. Perceived control reduces emotional stress in patients with heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:90–93. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapple CR, Artibani W, Cardozo LD, Castro-Diaz D, Craggs M, Haab F, et al. The role of urinary urgency and its measurement in the overactive bladder symptom syndrome: current concepts and future prospects. BJU Int. 2005;95:335–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher R, Gould D, Wainwright S, Fallon M. Quality of life after renal transplantation. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7:553–563. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1998.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rusinova K, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Azoulay E. Qualitative research: adding drive and dimension to clinical research. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S140–S146. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819207e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMillian W. Finding a method to analyze qualitative data: using a study of conceptual learning. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:53–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]