Abstract

Background Drinking alcohol has a long tradition in Chinese culture. However, data on the prevalence and patterns of alcohol consumption in China, and its main correlates, are limited.

Methods During 2004–08 the China Kadoorie Biobank recruited 512 891 men and women aged 30–79 years from 10 urban and rural areas of China. Detailed information on alcohol consumption was collected using a standardized questionnaire, and related to socio-demographic, physical and behavioural characteristics in men and women separately.

Results Overall, 76% of men and 36% of women reported drinking some alcohol during the past 12 months, with 33% of men and 2% of women drinking at least weekly; the prevalence of weekly drinking in men varied from 7% to 51% across the 10 study areas. Mean consumption was 286 g/week and was higher in those with less education. Most weekly drinkers habitually drank spirits, although this varied by area, and beer consumption was highest among younger drinkers; 37% of male weekly drinkers (12% of all men) reported weekly heavy drinking episodes, with the prevalence highest in younger men. Drinking alcohol was positively correlated with regular smoking, blood pressure and heart rate. Among male weekly drinkers, each 20 g/day alcohol consumed was associated with 2 mmHg higher systolic blood pressure. Potential indicators of problem drinking were reported by 24% of male weekly drinkers.

Conclusion The prevalence and patterns of drinking in China differ greatly by age, sex and geographical region. Alcohol consumption is associated with a number of unfavourable health behaviours and characteristics.

Keywords: Alcohol, drinking, cohort study, descriptive analysis, China

Introduction

Drinking alcohol is an established part of Chinese culture, often taking place during festivals and celebrations, with toasting at banquets or during business meetings.1 Alcohol production in China may date back several thousand years, and traditional types of alcoholic drink include fermented and distilled beverages made from rice or wheat.2 Over the past few decades, China has undergone rapid economic development and urbanization, and alcohol production and availability have increased; annual adult per capita consumption rose from below 2 litres of alcohol in 1981 to 5.9 litres in 2005.3,4 The prevalence of alcohol dependence and several alcohol-related diseases has also increased.5,6

Prospective studies, mainly in European or North American populations, have shown that alcohol consumption, especially heavy drinking, can cause liver cirrhosis, pancreatitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, injuries, mental illness and certain types of cancer (e.g. mouth, oesophagus, liver).7,8 Light to moderate drinking, however, has been associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases.9,10 As well as amount, the patterns of drinking (e.g. heavy drinking episodes) and exposure to other risk factors may modify the health effects of alcohol.7,11,12 An understanding of the patterns and main correlates of alcohol consumption is therefore essential for an unbiased assessment of the health effects of alcohol use in different populations. However, there is limited large-scale evidence on drinking patterns and the correlates of alcohol use in China.5,6,13,14

We report here the prevalence and patterns of alcohol consumption, and investigate the relationship between alcohol consumption and socio-demographic and health-related characteristics, among 512 891 men and women, using cross-sectional data collected during the baseline survey of the China Kadoorie Biobank.15,16

Methods

Study design and participants

The study objectives and design are described elsewhere.15,16 In brief, 512 891 men and women aged 30–79 years (mean 52 years) were enrolled between 2004 and 2008 from 10 diverse rural and urban areas in China, selected according to local disease patterns, exposure to certain risk factors, population stability, quality of death and disease registries, local commitment and capacity. Within each area, permanent residents without major disability in each of 100–150 administrative units (rural villages or urban residential committees) selected for the study were identified from local records and sent an invitation letter and leaflet inviting them to participate. The participation rate was 33% in rural areas and 27% in urban areas, and the main reasons for non-participation (reported anecdotally by field staff) were absence from the home and reluctance to spend a few hours visiting the screening centre.

The baseline survey was conducted in local assessment centres set up specifically for the study. Trained health workers administered a standardized questionnaire using a laptop-based direct data-entry system, with built-in functions to avoid logical errors and missing items. It included detailed questions on general demographic and socioeconomic status, medical history and health status, smoking, alcohol drinking, diet, physical activity and other lifestyle behaviours.

Physical measurements were made including height, weight, waist and hip circumference, heart rate and blood pressure. Blood pressure was measured twice using a UA-779 digital monitor after participants had remained at rest in a seated position for at least 5 min. A 10-ml blood sample was collected, and a venous blood spot test for random glucose level was done. The physical measurement procedures were standardized across the 10 study areas, and all physical measurements were made by trained study personnel. All devices used were regularly maintained and calibrated to ensure consistency of measurements.

Ethical approval for the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Beijing, China) and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee, University of Oxford (UK). All participants provided written informed consent.

Assessment of alcohol consumption

In the baseline survey questionnaire, participants were asked how often they had drunk alcohol during the previous 12 months (never or almost never; occasionally; only at certain seasons; every month but less than weekly; usually at least once a week). Those who had not drunk weekly in the past 12 months were asked if there was period of at least a year prior to that when they had drunk some alcohol at least once a week.

Those who had drunk weekly in the past 12 months were asked further questions about: frequency of drinking (1–2, 3–5 or 6–7 days per week); types of beverage (beer, grape wine, rice wine, weak spirits <40% alcohol content, strong spirits ≥40% alcohol content) and amount of alcohol drunk [reported by number of small (250 ml) or large (640 ml) bottles for beer, and number of liang (50 g) for wines and spirits] both on a typical drinking day, on special occasions and at the last time of drinking; experience of indicators of problem drinking in the past month (drinking in the morning, unable to work or do anything due to drinking, depressed, irritated or loss of control due to drinking, unable to stop drinking, shakes when stopping drinking); time of drinking in relation to meals; at what age they started drinking weekly; whether their consumption had changed significantly in the past few years; and the experience of flushing or dizziness after drinking, which in China is often due to genetically determined deficiency in alcohol metabolizing enzymes.17

For this report, participants were classified into five main drinking categories: abstainers were defined as those who had never or almost never drunk alcohol in the past 12 months and had not drunk weekly in the past; ex-weekly drinkers as those who had never or almost never drunk alcohol in the past 12 months but had drunk weekly in the past; reduced-intake drinkers as those who had drunk alcohol occasionally, at certain seasons, or every month but less than weekly, in the past 12 months but had drunk weekly in the past; occasional drinkers as those who had drunk alcohol occasionally, at certain seasons, or every month but less than weekly, in the past 12 months and had not drunk weekly in the past; and weekly drinkers as those who usually drank alcohol at least once a week during the past 12 months. These drinking categories are broadly in line with those discussed in the World Health Organization (WHO) guide for monitoring alcohol consumption,18 but use the additional information collected in the study questionnaire to classify participants based on current or past weekly drinking, which may have implications for assessing reliably the health effects of alcohol consumption.

Level of alcohol consumption was calculated as grams of pure alcohol per week, based on the beverage type, amount drunk and frequency (days per week), assuming the following alcohol content by volume (v/v) typically seen in China:2 beer 4%, grape wine 12%, rice wine 15%, weak spirits 38% and strong spirits 53%. Only one beverage type was allowed to be reported for a typical drinking day, and this defined the type of beverage drunk habitually. This is a limitation of the study questionnaire, but is in line with a previous study we conducted in China where over 95% of drinkers consumed a single beverage type.13 Heavy drinking episodes were classified as the consumption of >60 g of alcohol on one occasion for men, and >40 g for women.18

Statistical methods

Percentages of the population in each category of alcohol consumption, and the mean alcohol consumption per week, were directly standardized to the age (in 10-year groups) and area (10 groups) structure of the study population. Associations between socio-demographic variables and alcohol drinking category were evaluated with a chi-square test for association, controlling for age and area. Associations of mean weekly alcohol consumption with these variables were evaluated using the type III Wald chi-square from a general linear model, adjusted for age and area.

Baseline characteristics presented by drinking category were also directly standardized as above. For variables measured in weekly drinkers, standardization was done according to the age and area structure of weekly drinkers. Heterogeneity of baseline characteristics across drinking categories, and trend by amount drunk in weekly drinkers, were evaluated with a type III Wald chi-square from a logistic or general linear model, adjusted for age and area. Analyses further adjusted for smoking status used the smoking categories current regular, ex-regular, occasional and never.

All analyses were done separately by gender. Analyses were done in SAS version 9.2.

Results

Overall, 76% of men and 36% of women surveyed reported having drunk some alcohol in the past year, with 33% of men and 2% of women drinking at least weekly (Table 1). In men, the prevalence of weekly drinking was higher at younger ages, in urban areas and in those with higher income, but varied little by education. The mean amount of alcohol consumed by male weekly drinkers was 286 g/week (i.e. four drinks a day on average assuming one drink contains 10 g of pure alcohol), and was higher in rural than in urban drinkers (333 g/week vs 238 g/week, P < 0.001), and in drinkers with less education or lower income. In women the mean amount consumed by weekly drinkers was 116 g/week (i.e. one to two drinks a day) and was also higher in rural areas and in those with less education and income. The mean age at which weekly drinking started was 28 years in male and 38 years in female weekly drinkers. Nine percent of men were either ex-weekly drinkers or had reduced their intake from weekly drinking in the past to occasional drinking, and this prevalence increased with age. In men and women, the prevalence of occasional drinking was higher at younger ages, and in those with more education.

Table 1.

Prevalence of drinking alcohol and amount drunk, by socio-demographic characteristics

| Current non-drinkers |

Current drinkers |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly |

|||||||

| Abstainers | Ex-weekly | Reduced-intake | Occasional | Meanb (S.E.) | |||

| N | % | % | % | % | % | g/week | |

| Men | |||||||

| All | 210 222 | 20.3 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 37.7 | 33.3 | 286 (0.9) |

| Regiona | |||||||

| Urban | 91 339 | 15.1 | 3.1 | 5.3 | 38.0 | 38.5 | 238 (1.1) |

| Rural | 118 883 | 24.3 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 37.4 | 29.3 | 333 (1.4) |

| Age group (years)a | |||||||

| 30-39 | 29 594 | 14.2 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 48.0 | 33.8 | 256 (2.4) |

| 40-49 | 59 230 | 15.4 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 41.1 | 37.6 | 287 (1.6) |

| 50-59 | 63 715 | 19.7 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 36.2 | 34.7 | 301 (1.6) |

| 60-69 | 41 331 | 27.5 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 31.9 | 27.7 | 275 (2.0) |

| 70-79 | 16 352 | 33.6 | 8.1 | 5.6 | 29.5 | 23.2 | 244 (3.4) |

| Highest education levela | |||||||

| No formal school | 18 660 | 26.7 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 31.6 | 31.9 | 324 (11.8) |

| Primary school | 70 110 | 22.0 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 35.0 | 33.7 | 311 (3.5) |

| Middle/high school | 104 899 | 19.4 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 39.1 | 33.0 | 272 (1.6) |

| College/university | 16 553 | 16.0 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 46.0 | 29.9 | 210 (6.0) |

| Annual household income (yuan)a | |||||||

| <10 000 | 54 737 | 23.7 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 35.9 | 30.8 | 300 (3.8) |

| 10 000-19 999 | 59 558 | 20.9 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 37.1 | 33.1 | 291 (1.9) |

| 20 000-34 999 | 53 400 | 19.3 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 37.8 | 34.0 | 284 (2.2) |

| ≥35 000 | 42 527 | 16.2 | 3.3 | 6.3 | 36.7 | 37.5 | 274 (3.2) |

| Occupationa | |||||||

| Agricultural | 91 274 | 24.5 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 34.8 | 32.6 | 312 (3.5) |

| Factory | 40 224 | 18.6 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 38.8 | 35.1 | 283 (4.1) |

| Professional/sales | 32 529 | 16.4 | 3.2 | 5.7 | 39.7 | 35.0 | 268 (3.3) |

| Retired/other | 46 195 | 25.8 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 32.9 | 29.1 | 304 (6.2) |

| Women | |||||||

| All | 302 669 | 63.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 33.5 | 2.1 | 116 (1.6) |

| Regiona | |||||||

| Urban | 134 847 | 60.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 36.5 | 2.1 | 68 (1.5) |

| Rural | 167 822 | 65.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 31.3 | 2.1 | 150 (2.4) |

| Age group (years)a | |||||||

| 30-39 | 48 210 | 57.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 40.3 | 1.5 | 93 (4.4) |

| 40-49 | 93 519 | 58.8 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 38.5 | 2.1 | 115 (2.8) |

| 50-59 | 93 841 | 65.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 31.7 | 2.1 | 119 (3.0) |

| 60-69 | 50 440 | 70.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 25.6 | 2.4 | 111 (3.1) |

| 70-79 | 16 659 | 73.7 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 22.1 | 2.6 | 105 (5.0) |

| Highest education levela | |||||||

| No formal school | 76 561 | 71.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 25.6 | 2.3 | 133 (4.6) |

| Primary school | 95 106 | 67.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 29.6 | 1.8 | 120 (5.4) |

| Middle/high school | 117 541 | 60.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 36.3 | 2.0 | 103 (3.5) |

| College/university | 13 461 | 47.8 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 49.7 | 2.1 | 106 (4.8) |

| Annual household income (yuan)a | |||||||

| <10 000 | 90 095 | 67.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 29.5 | 1.9 | 122 (3.1) |

| 10 000-19 999 | 89 455 | 64.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 32.6 | 1.8 | 114 (3.2) |

| 20 000-34 999 | 73 321 | 61.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 35.8 | 2.0 | 108 (5.9) |

| ≥35 000 | 49 798 | 57.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 39.0 | 2.7 | 95 (10.6) |

| Occupationa | |||||||

| Agricultural | 122 733 | 70.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 26.4 | 2.1 | 141 (2.5) |

| Factory | 32 171 | 62.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 35.0 | 2.1 | 102 (16.6) |

| Professional/sales | 33 644 | 57.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 39.2 | 2.7 | 115 (21.4) |

| Retired/other | 114 121 | 67.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 29.7 | 1.7 | 114 (8.5) |

Prevalences and means are adjusted for age and area, as appropriate.

aAssociations between alcohol drinking category and socio-demographic variables, after adjusting for age and area, were evaluated with a chi-square test for association: P < 0.0001 across all variables in men and women.

bDifferences in mean alcohol intake across variables, after adjusting for age and area, were assessed using a general linear model: P < 0.0001 across all variables except age in women (P = 0.005).

Most male and female weekly drinkers consumed spirits on a typical drinking day (70% and 62%, respectively). In rural areas, strong spirits were consumed by 62% of male drinkers and 76% of female drinkers (Table 2). Weak spirits were also commonly consumed by rural drinkers (26% of men and 13% of women). In urban areas, 32% of male drinkers drank strong spirits, 30% beer, 20% weak spirits and 17% rice wine. Female urban drinkers drank beer (41%), grape wine (22%), strong spirits (16%) and weak spirits (13%). Strong-spirit drinkers consumed on average over twice as much alcohol (mean 352 g/week in men, 163 g/week in women) as those who drank beer (146 g/week in men, 60 g/week in women). Considering the proportion drinking each beverage type and the mean amount consumed (Table 2), 82% of the alcohol (g/week) consumed by weekly drinkers in the study population came from spirits (59% from strong spirits and 23% from weak spirits) with beer, rice wine and grape wine accounting for 10%, 8% and <1%, respectively.

Table 2.

Type of alcohol and amount consumed in weekly drinkers, by region

| Strong spirits (≥40% v/v) |

Weak spirits (<40% v/v) |

Beer |

Rice wine |

Grape wine |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (S.E.) | Mean (S.E.) | Mean (S.E.) | Mean (S.E.) | Mean (S.E.) | |||||||

| N | % | g/week | % | g/week | % | g/week | % | g/week | % | g/week | |

| Men | |||||||||||

| All | 69 904 | 46.8 | 352 (1.5) | 22.8 | 298 (1.9) | 18.2 | 146 (1.3) | 11.3 | 209 (2.1) | 0.9 | 73 (4.0) |

| Rural | 34 881 | 61.5 | 373 (2.0) | 25.7 | 318 (2.6) | 6.4 | 118 (3.1) | 6.2 | 227 (4.0) | 0.3 | 119 (13.2) |

| Urban | 35 023 | 32.2 | 315 (2.2) | 20.1 | 273 (2.6) | 29.7 | 153 (1.4) | 16.6 | 202 (2.5) | 1.5 | 66 (4.2) |

| Women | |||||||||||

| All | 6248 | 49.1 | 163 (2.6) | 12.7 | 97 (4.0) | 22.2 | 60 (1.8) | 6.2 | 66 (4.1) | 9.8 | 30 (1.2) |

| Rural | 3428 | 75.9 | 173 (2.9) | 12.8 | 99 (4.9) | 4.8 | 59 (6.1) | 5.1 | 80 (6.5) | 1.4 | 37 (4.8) |

| Urban | 2820 | 16.0 | 120 (4.9) | 13.3 | 97 (6.7) | 40.7 | 63 (1.8) | 8.2 | 55 (5.3) | 21.7 | 31 (1.3) |

Prevalences and means are adjusted for age.

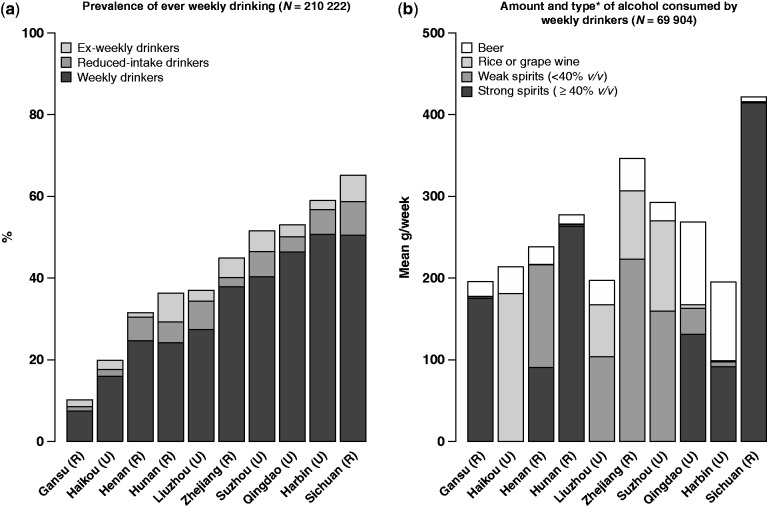

There was large variation in the prevalence and patterns of drinking by study area in both men and women (see Supplementary Figure 1 for a map showing the location of the 10 study areas, available at IJE online). In men, the prevalence of current weekly drinking ranged from 7% (Gansu) to 51% (Harbin) and the mean amount consumed per drinker from 195 g/week (Harbin) to 422 g/week (Sichuan) (Figure 1). Spirit drinking, particularly strong spirits, was predominant in four rural areas (Sichuan, Henan, Hunan and Gansu), beer drinking common only in the two most northern cities (Harbin and Qingdao) and wine drinking (mainly rice wine) frequent in southern and coastal areas (Liuzhou, Haikou, Suzhou and Zhejiang). Substantial regional variation was also seen in women, with the prevalence of current weekly drinking ranging from 0.2% (Gansu) to 6% (Sichuan) and mean consumption from 53 g/week (Liuzhou) to 182 g/week (Sichuan) (Supplementary Figure 2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of drinking and amount and type of alcohol drunk among men, in the 10 study areas. Prevalence estimates and mean amount drunk are adjusted for age. The shaded areas in (b) represent the proportion (%) of drinkers in each area consuming each type of alcohol (*only one type was reported for each drinker). Areas are ordered by prevalence of ever weekly drinking. U, urban; R, rural

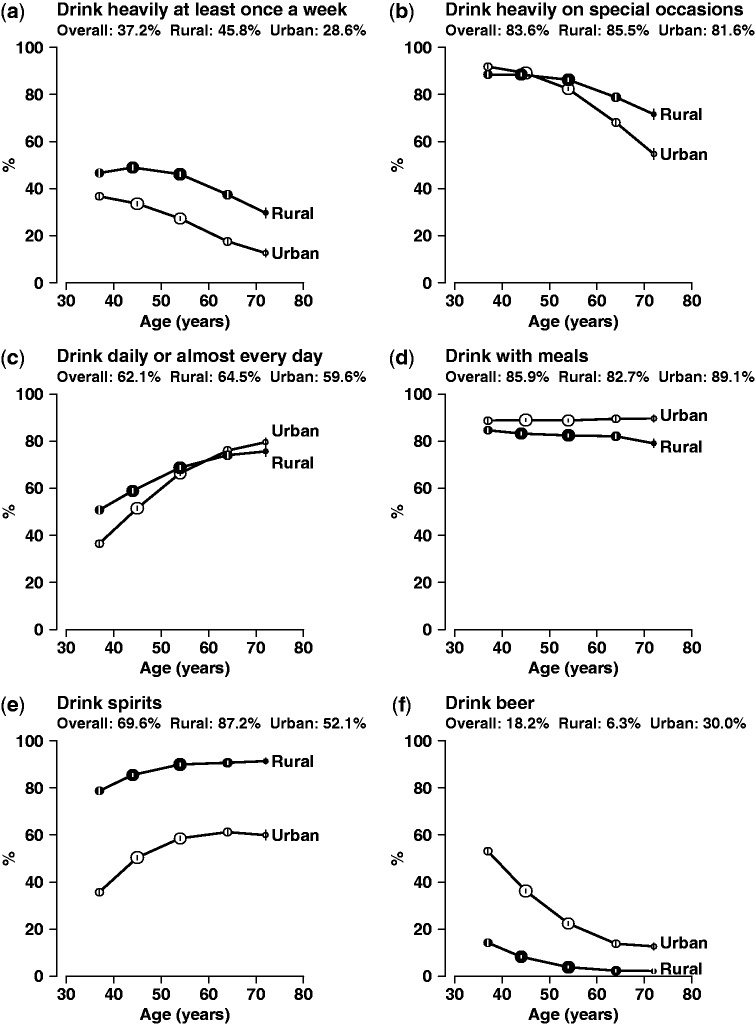

A high proportion of male weekly drinkers reported heavy drinking episodes (i.e. >60 g of alcohol in a drinking session) on a weekly basis (37%) or on special occasions (84%), and the prevalence was generally highest at younger ages (Figure 2). Drinking daily or almost daily was reported by 62% of male weekly drinkers (21% of all men), and the prevalence increased sharply with age. At all ages most male weekly drinkers usually drank with meals (86% overall), but this varied greatly by area from 20% (Gansu) to 99% (Suzhou). Beer drinking was more common among younger people, with 34% of male weekly drinkers aged 30–39 years drinking beer compared with 8% of those aged 70–79 years. Conversely younger drinkers, particularly in urban areas, were less likely than older drinkers to drink spirits. Drinking patterns by age and region in the 6248 female weekly drinkers were broadly similar to those in men (Supplementary Figure 3, available as Supplementary data at IJE online)

Figure 2.

Drinking patterns in 69 904 male weekly drinkers, by age group. The prevalence in weekly drinkers in urban and rural regions of: (a) drinking heavily (>60 g in one session) at least once a week; (b) drinking heavily on special occasions; (c) drinking daily or almost every day; (d) drinking usually with meals; (e) drinking spirits; (f) drinking beer. Values are plotted at the mean age of each 10-year age group. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. The circle area is proportional to the sample size

In both men and women, heart rate and blood pressure were positively associated with amount of alcohol consumed. In male weekly drinkers, each 140 g/week (or 20 g/day) of alcohol consumed was associated with approximately 2 mmHg higher systolic and 1 mmHg higher diastolic blood pressure, and 1 beat per min higher heart rate (Table 3). There was no apparent relationship between alcohol consumption and body mass index in men or women, although waist:hip ratio tended to be slightly higher in heavy drinkers (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Table 3.

Association of alcohol consumption with selected variables in 210 222 men

| Current non-drinkers |

Current drinkers |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount drunk by weekly drinkers Category (g/week) (mean of each category) |

||||||||||||

| Abstainers | Ex-weekly | Reduced- intake | Occasional | Weekly | <140 (80) | 140-279 (223) | 280-419 (370) | 420+ (690) | P-trenda | Heavy episodic drinking | ||

| Number of men (N) | 42 764 | 7923 | 10 371 | 79 260 | 69 904 | 25 096 | 18 910 | 12 830 | 13 068 | 26 014 | ||

| Mean age (years) | 56.5 | 58.7 | 54.6 | 50.5 | 51.0 | 51.0 | 51.2 | 50.3 | 49.7 | 0.0001 | 49.3 | |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 | 23.7 | 24.0 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 23.6 | 0.03 | 24.0 | |

| Mean waist:hip ratio | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 | <0.0001 | 0.92 | |

| Mean SBP (mmHg) | 131.9 | 134.2 | 133.7 | 131.0 | 134.3 | 132.1 | 134.5 | 135.9 | 137.7 | <0.0001 | 136.7 | |

| Mean DBP (mmHg) | 78.3 | 79.7 | 79.6 | 78.2 | 80.4 | 79.1 | 80.4 | 81.4 | 82.3 | <0.0001 | 82.6 | |

| Mean heart rate (beats/minute) | 77.9 | 78.9 | 77.8 | 76.9 | 78.4 | 77.2 | 78.3 | 79.2 | 81.0 | <0.0001 | 79.9 | |

| Mean random blood glucose (mmol/L) | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.0 | <0.0001 | 6.1 | |

| Mean MET hours/week | 9.1 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 0.32 | 9.8 | |

| Regular smoker (%) | 52.3 | 53.6 | 64.7 | 56.9 | 71.7 | 65.8 | 73.1 | 76.3 | 79.8 | <0.0001 | 77.4 | |

| Regular tea-drinker (%) | 43.1 | 46.7 | 52.8 | 46.7 | 60.0 | 58.9 | 59.1 | 59.6 | 62.1 | <0.0001 | 62.4 | |

| Self-reported poor health (%) | 12.8 | 23.5 | 14.0 | 7.7 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 0.95 | 6.8 | |

| History of chronic diseaseb (%) | 27.3 | 46.0 | 33.5 | 21.2 | 17.9 | 19.2 | 17.8 | 17.1 | 18.0 | <0.0001 | 18.1 | |

| Flushing response after drinking (%) | 18.0 | 24.1 | 16.2 | 13.3 | 8.4 | <0.0001 | 12.0 | |||||

| Problem drinking indicatorsc (%) | 23.9 | 10.7 | 23.1 | 31.6 | 41.5 | <0.0001 | 33.2 | |||||

Prevalences and means are adjusted for age and area. BMI, body mass index; S/DBP systolic/diastolic blood pressure; MET, metabolic equivalent task.

aP for trend by amount drunk category within weekly drinkers (P for heterogeneity across the five main drinking categories was <0.0001 for all variables).

bDiagnosed with one or more of: coronary heart disease, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, diabetes, cancer, tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis/cirrhosis, rheumatoid arthritis, peptic ulcer; chronic respiratory disease, gallstone/gallbladder disease, kidney disease.

cReporting one or more in the past month of: drinking in the morning, unable to work or do anything due to drinking; depressed irritated or lost control due to drinking; couldn't stop drinking; had shakes when stopped drinking.

There was a strong correlation between drinking alcohol and smoking in men, with the prevalence of current regular (i.e. weekly) smoking lowest in abstainers (52%), and highest (80%) in the heaviest drinkers. As smoking may confound relationships between alcohol and health-related characteristics, analyses were also done adjusted for smoking status, which did not materially alter the associations (data not shown). Current weekly tea drinking was also correlated with alcohol consumption in men (43% in abstainers compared with 62% in the heaviest drinkers). Ex-weekly drinkers, followed by those who had reduced their intake, reported the highest levels of physician-diagnosed chronic diseases and were most likely to self-report poor health among men and women (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

A flushing response (hot flushes or dizziness) after drinking a small amount of alcohol was reported by 18% of men and 24% of women who drank weekly. This prevalence was inversely associated with amount drunk (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1), and on average those who experienced a flushing response after drinking consumed less alcohol compared with those who did not (mean 205 g/week vs 303 g/week in men, 98 g/week vs 121 g/week in women, both P < 0.0001). The prevalence of flushing did not vary much with age, but in male weekly drinkers it ranged from 8% (Haikou) to 29% (Sichuan) across the 10 study areas (data not shown).

Potential indicators of problem drinking (including one or more of: drinking in the morning, being unable to work or do anything due to drinking; feeling depressed, irritated or losing control due to drinking; being unable to stop drinking; and having shakes when stopping drinking) were reported by 11% of male weekly drinkers consuming <140 g/week compared with 42% of men consuming over 420 g/week (Table 3), and by 4% of female weekly drinkers consuming <70 g/week compared with 30% of women drinking over 280 g/week (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

This is one of the largest studies of the prevalence and patterns of alcohol consumption in China. In this study, drinking alcohol was much more frequent in men than women and there was striking regional variation in drinking patterns as well as in the types of alcohol consumed, reflecting the level of geographical, economic and cultural diversity present within China. A clustering of lifestyle behaviours associated with alcohol drinking was also observed, with weekly drinkers more likely to smoke and drink tea regularly. Most people drank with meals, largely reflecting traditional Chinese customs; however, heavy episodic drinking was common among younger people, perhaps reflecting a tendency towards more Western drinking styles. Although the study was not designed to be nationally representative, these results provide unique and reliable information about drinking habits in China at a time of rapid economic and social change, when there is a growing risk of alcohol-related health problems.

The overall findings in our study are broadly consistent with those from a nationally representative study of 220 000 men in China, conducted in 1990–91, where the prevalence of regular drinking was also 33%, and heavy consumption was more frequent in rural areas.13 A more recent nationally representative survey of 50 000 adults in 2007 reported 56% of men and 15% of women drinking alcohol in the past year.14 In a survey conducted in 2001 among 25 000 adults from five provinces, 75% of men and 39% of women reported drinking alcohol at least once in the past year,6 and in a similar survey conducted 6 years earlier, the rates were 84% in men and 29% in women.5 Other studies conducted in particular regions of China have reported the prevalence of drinking ranging from 58 to 90% for men and 12 to 55% for women.19–21 Although the overall prevalence and frequency of alcohol drinking in this Chinese population is lower than that typically seen in many Western populations,4 the regional variation observed is probably much more extreme. This is consistent with the substantial regional variation in alcohol drinking reported in a survey of 69 rural counties in China in 1989, in which the prevalence of ever regular drinking (at least three times a week for more than 6 months) in men varied from 3% to 82% across study sites.22 In common with previous reports from China and elsewhere,23 drinking prevalence and consumption levels in our study were much higher among men than women.

A major characteristic of alcohol drinking in China is the widespread consumption of strong spirits in many parts of the country, particularly in the inland rural regions. In the study of 220 000 Chinese men, of whom three-quarters were from rural regions,13 93% were strong spirit drinkers, which was comparable with some of the rural regions in our study. In our study population, over 80% of alcohol consumed was from spirits and 10% from beer. WHO recently reported that 57% of per capita alcohol consumption in China was from spirits and 34% from beer.4 These differences could be due to the much younger population of adults aged 15 years or above or the different regions surveyed in the WHO report. In the 2001 survey of 25 000 adults in five provinces, which had a large proportion of young people aged below 30 years from urban areas, beer was the most popular drink in their study population, followed by strong spirits.6 In our study population aged 30–79 years, beer drinking was most frequent among the younger drinkers, and was highest in Harbin and Qingdao, two northern cities which are famous for their beer production. Weaker spirits and traditional rice wine were relatively favoured in the more prosperous coastal and southern areas in our study, and consumption of grape wine was generally very low in all areas.

Smoking and alcohol consumption were highly correlated, as has been observed previously in China and elsewhere.24,25 This must be considered when assessing the health affects of alcohol, although adjustment for smoking did not substantially affect the correlations between alcohol and baseline health characteristics in our study. Drinking alcohol was also associated with tea drinking (mainly green tea), which may have some benefits for health.26,27 Whereas weekly drinking was most common among men living in urban areas, the heaviest drinkers tended to live in rural areas and have poorer education—patterns fairly consistent with other studies in China.20,28 People with high socioeconomic status (e.g. greater education or income) were more likely than others to be occasional drinkers or, if weekly drinkers, to consume less, which may in turn represent a grouping of lifestyle and socioeconomic factors potentially advantageous to health.29

Apart from the total amount consumed, patterns of consumption are also likely to influence the health effects of alcohol.7 Heavy drinking episodes (or ‘binge drinking’) may be particularly harmful to health and also increase the risk of injury and other immediate adverse consequences.18 Binge drinking among adolescents and young people has been rising in many Western populations, causing significant public health concern,30 and in this adult population both weekly and occasional binge drinking were higher among younger people. A similar trend was also reported in a survey of 10 000 Chinese adults in Hong Kong,31 and a survey of 54 000 adolescents in 18 provincial capitals in China found 30% started to drink before the age of 13 years, and 10% reported at least one episode of binge drinking.32 Conversely, drinking alcohol with meals, which is thought to be less harmful to health,33 is a common custom in China and was seen widely in the present study.

As expected, ex-weekly drinkers and those who had reduced their intake were more likely to have poor health status. This is particularly relevant to the appropriate control of reverse causality when assessing the prospective association of alcohol drinking with disease risks in the future.29 Also as expected, a proportion of the population experienced flushing and dizziness in response to alcohol, symptoms of a deficiency in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes which is common in East Asian populations, and may modify the health effects of drinking alcohol.17,34 The observed association between blood pressure and alcohol consumption, a phenomenon widely reported in many populations, is of a similar magnitude to that reported in other studies i.e. an increase of approximately 2 mmHg systolic blood pressure per 20 g alcohol consumed each day,35 which provides an important measure of validation for the self-reported alcohol measures collected in the present study.

To conclude, this large survey found that drinking alcohol remains a predominantly male phenomenon in Chinese adults, although for both men and women there is large heterogeneity in the prevalence and patterns of drinking by area, age, socioeconomic status and other lifestyle behaviours. The wide diversity of alcohol exposures in China creates particular challenges as well as opportunities for evaluating the health effects of alcohol consumption. Large prospective studies like the CKB with a range of measures for alcohol (as well as for other lifestyle and environmental factors), done in many different parts of China, will help to improve our understanding of the effects of alcohol on a wide range of fatal and non-fatal conditions in this country.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at IJE online.

Funding

The CKB baseline survey and first re-survey in China were supported by the Kadoorie Charitable Foundation in Hong Kong; follow-up of the project during 2009–14 is supported by the Wellcome Trust in the UK (grant 088158/Z/09/Z); the Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU) at Oxford University also receive core funding for the study from the UK Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation and Cancer Research UK.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Judith MacKay in Hong Kong; Yu Wang, Gonghuan Yang, Zhengfu Qiang, Lin Feng, Maigen Zhou, Wenhua Zhao and Yan Zhang in China CDC; Lingzhi Kong, Xiucheng Yu and Kun Li in the Ministry of Health of China; and Yiping Chen, Sarah Clark, Martin Radley, Hongchao Pan and Jill Boreham in the CTSU, Oxford, for assisting with the design, planning, organization, conduct of the study and data analysis. The most important acknowledgement is to the participants in the study and the members of the survey teams in each of the 10 regional centres, as well as to the project development and management teams based at Beijing, Oxford and the 10 regional centres. CTSU acknowledges support from the BHF Centre of Research Excellence, Oxford.

Members of CKB collaborative group:

International Steering Committee: Liming Li, Zhengming Chen, Junshi Chen, Rory Collins, Fan Wu (ex-member), Richard Peto

- Study coordinating centres:

- International (ICC, Oxford): Zhengming Chen, Garry Lancaster, Xiaoming Yang, Alex Williams, Margaret Smith, Ling Yang, Yumei Chang, Iona Millwood, Yiping Chen, Qiuli Zhang, Sarah Lewington, Gary Whitlock

- National (NCC, Beijing): Yu Guo, Guoqing Zhao, Zheng Bian, Lixue Wu, Can Hou

- Regional (RCC, 10 areas in China):

- Qingdao

- Qingdao CDC: Zengchang Pang, Shaojie Wang, Yun Zhang, Kui Zhang

- Licang CDC: Silu Liu

- Heilongjiang

- Provincial CDC: Zhonghou Zhao, Shumei Liu, Zhigang Pang

- Nangang CDC: Weijia Feng, Shuling Wu, Liqiu Yang, Huili Han, Hui He

- Hainan

- Provincial CDC: Xianhai Pan, Shanqing Wang, Hongmei Wang

- Meilan CDC: Xinhua Hao, Chunxing Chen, Shuxiong Lin

- Jiangsu

- Provincial CDC: Xiaoshu Hu, Minghao Zhou, Ming Wu

- Suzhou CDC: Yeyuan Wang, Yihe Hu, Liangcai Ma, Renxian Zhou, Guanqun Xu

- Guangxi

- Provincial CDC: Baiqing Dong, Naying Chen, Ying Huang

- Liuzhou CDC: Mingqiang Li, Jinhuai Meng, Zhigao Gan, Jiujiu Xu, Yun Liu

- Sichuan

- Provincial CDC: Xianping Wu, Yali Gao, Ningmei Zhang

- Pengzhou CDC: Guojin Luo, Xiangsan Que, Xiaofang Chen

- Gansu

- Provincial CDC: Pengfei Ge, Jian He, Xiaolan Ren

- Maiji CDC: Hui Zhang, Enke Mao, Guanzhong Li, Zhongxiao Li, Jun He

- Henan

- Provincial CDC: Guohua Liu, Baoyu Zhu, Gang Zhou, Shixian Feng

- Huixian CDC: Yulian Gao, Tianyou He, Li Jiang, Jianhua Qin, Huarong Sun

- Zhejiang

- Provincial CDC: Liqun Liu, Min Yu, Yaping Chen

- Tongxiang CDC: Zhixiang Hu, Jianjin Hu, Yijian Qian, Zhiying Wu, Lingli Chen

- Hunan

- Provincial CDC: Wen Liu, Guangchun Li, Huilin Liu

- Liuyang CDC: Xiangquan Long, Youping Xiong, Zhongwen Tan, Xuqiu Xie, Yunfang Peng

Conflict of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

In the China Kadoorie Biobank population of middle-aged adults, drinking alcohol was much more frequent in men than in women.

The prevalence and patterns of drinking varied widely by study area. Spirits were the most commonly consumed beverage, with strong spirits (over 40% alcohol content) predominant, particularly in rural areas.

Heavy drinking episodes were widespread in men, on a regular basis as well as on special occasions, particularly among those aged below 50 years.

Clustering of socio-demographic and behavioural factors potentially influencing health is seen, with heavy alcohol consumption correlated with lower education levels and regular smoking.

Alcohol consumption is positively associated with systolic blood pressure, which provides validation of the self-reported alcohol intake measured in the study questionnaire.

References

- 1.Hao W, Chen H, Su Z. China: alcohol today. Addiction. 2005;100:737–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochrane J, Chen H, Conigrave KM, Hao W. Alcohol use in China. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:537–42. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei H, Derson Y, Xiao S, Li L, Zhang Y. Alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems: Chinese experience from six area samples, 1994. Addiction. 1999;94:1467–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941014673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao W, Su Z, Liu B, et al. Drinking and drinking patterns and health status in the general population of five areas of China. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:43–52. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010;105:817–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schutze M, Boeing H, Pischon T, et al. Alcohol attributable burden of incidence of cancer in eight European countries based on results from prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1584. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrao G, Rubbiati L, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Poikolainen K. Alcohol and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2000;95:1505–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d671. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1705–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaridze D, Brennan P, Boreham J, et al. Alcohol and cause-specific mortality in Russia: a retrospective case-control study of 48,557 adult deaths. Lancet. 2009;373:2201–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L, Zhou M, Sherliker P, et al. Alcohol drinking and overall and cause-specific mortality in China: nationally representative prospective study of 220 000 men with 15 years of follow-up. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1101–13. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Jiang Y, Zhang M, et al. Drinking behaviour among men and women in China: the 2007 China Chronic Disease and Risk Factor Surveillance. Addiction. 2011;106:1946–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Lee L, Chen J, et al. Cohort profile: The Kadoorie Study of Chronic Disease in China (KSCDC) Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1243–49. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Chen J, Collins R, et al. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1652–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eng MY, Luczak SE, Wall TL. ALHD2, ADH1B, and ADH1C genotypes in Asians: a literature review. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30:22–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO) International Guide for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption and Related Harm. Geneva: WHO; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei H, Young D, Lingjiang L, et al. Psychoactive substance use in three sites in China: gender differences and related factors. Addiction. 1995;90:1503–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901115039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, Su Z, Deng H, Xiang X, Chen H, Hao W. A comparative survey on alcohol and tobacco use in urban and rural populations in the Huaihua District of Hunan Province, China. Alcohol. 2006;39:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Casswell S, Cai H. Increased drinking in a metropolitan city in China: a study of alcohol consumption patterns and changes. Addiction. 2008;103:416–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Peto R, Pan W, Liu B, Campbell TC. Mortality, Biochemistry, Diet and Lifestyle in Rural China. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: Patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng H, Lee S, Tsang A, et al. The epidemiological profile of alcohol and other drug use in metropolitan China. Int J Public Health. 2010;55:645–53. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poortinga W. The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an English adult population. Prev Med. 2007;44:124–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan LC, Koh WP, Yuan JM, et al. Differential effects of black versus green tea on risk of Parkinson's disease in the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:553–60. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arab L, Liu W, Elashoff D. Green and black tea consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:1786–92. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.538470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu B, Mao ZF, Rockett IR, Yue Y. Socioeconomic status and alcohol use among urban and rural residents in China. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:952–66. doi: 10.1080/10826080701204961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emberson JR, Bennett DA. Effect of alcohol on risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: causality, bias, or a bit of both? Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2:239–49. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Editors. Calling time on young people's alcohol consumption. Lancet. 2008;371:871. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JH, Lee S, Chow J, et al. Prevalence and the factors associated with binge drinking, alcohol abuse, and alcohol dependence: a population-based study of Chinese adults in Hong Kong. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:360–70. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing Y, Ji C, Zhang L. Relationship of binge drinking and other health-compromising behaviors among urban adolescents in China. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gentry RT. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of alcohol absorption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:403–04. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puddey IB, Beilin LJ. Alcohol is bad for blood pressure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:847–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.