Abstract

Objective

Invasive pneumococcal disease is a major cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States, particularly among the elderly (>65 years). There are large racial disparities in pneumococcal vaccination rates in this population. Here, we estimate the cost-effectiveness of a hypothetical national vaccination intervention program designed to eliminate racial disparities in pneumococcal vaccination in the elderly.

Methods

In an exploratory analysis, a Markov decision-analysis model was developed, taking a societal perspective and assuming a 1-year cycle length, 10-year vaccination program duration, and lifetime time horizon. In the base-case analysis, it was conservatively assumed that vaccination program promotion costs were $10 per targeted minority elder per year, regardless of prior vaccination status and resulted in the elderly African American and Hispanic pneumococcal vaccination rate matching the elderly Caucasian vaccination rate (65%) in year 10 of the program.

Results

The incremental cost-effectiveness of the vaccination program relative to no program was $45,161 per quality-adjusted life-year gained in the base-case analysis. In probabilistic sensitivity analyses, the likelihood of the vaccination program being cost-effective at willingness-to-pay thresholds of $50,000 and $100,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained was 64% and 100%, respectively.

Conclusions

In a conservative analysis biased against the vaccination program, a national vaccination intervention program to ameliorate racial disparities in pneumococcal vaccination would be cost-effective.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, disparities, invasive pneumococcal disease, vaccination

Introduction

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, causing 40,000 hospitalizations and 4,000 deaths annually [1]. Elderly populations are particularly vulnerable, with greater than 30% of IPD-attributable hospitalizations and 50% of IPD-attributable deaths occurring in this group [2].

The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) prevents IPD and is universally recommended at age 65 years in the United States [3,4]. Current pneumococcal vaccination rates in the elderly, however, remain far below the 90% goal set by the Healthy People 2010 objective, with substantial racial disparities; only 65% of Caucasians, 45% of African Americans, and 40% of Hispanics in this age group reported having ever received pneumococcal vaccination in 2009 [5]. Racial vaccination disparities are particularly concerning given significantly higher IPD incidence in African American, Hispanic, and Native-American populations [2,6–8].

Prior research suggests that national programs to reduce disparities in influenza vaccination in elderly minorities can be cost-effective [9]. This work, however, has not been extended to pneumococcal vaccination and, thus, it remains unclear as to whether a program to reduce disparities in pneumococcal vaccination would also be cost-effective. Here, a Markov decision-analysis model was used to assess the cost-effectiveness of a hypothetical national vaccination intervention program designed to eliminate known racial disparities in pneumococcal vaccination rates in the elderly. The goal of this exploratory analysis was to quantify broad cost and effectiveness parameters that a cost-effective vaccination program would need to satisfy, and not to specifically delineate program parameters.

Methods

Perspective and Model Cohort

In the base-case analysis, a societal perspective was taken, including both direct medical and direct nonmedical costs and following the reference case recommendations of the US Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine [10]. The model cohort was the combined 2006 US 65-year-old African-American and Hispanic birth cohort. We assumed that individuals had either not previously received the PPSV23 or, if they had, there was no residual IPD protective immunity.

Model Structure

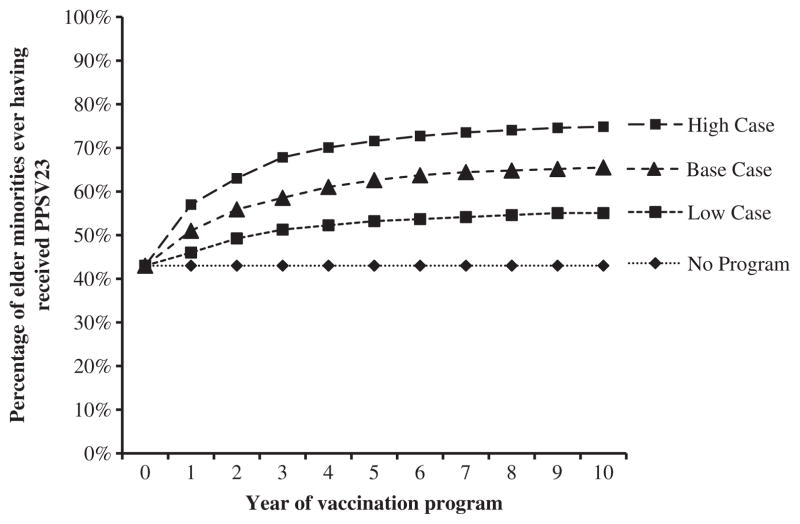

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of a hypothetical US national vaccination intervention program to eliminate racial disparities in pneumococcal vaccination rates, a Markov decision-analysis model was developed by using TreeAge Pro 2009 (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA). The model used a 1-year cycle length and a lifetime time horizon, examining a 10-year vaccination intervention program. The 10-year program duration allowed for assumptions regarding declining program impact on population vaccination rates and declining vaccination-related IPD immunity with time. In both the intervention and no-intervention arms of the model, the target population began in a well (-unvaccinated) health state and transitioned to well (-vaccinated), IPD, disabled, or dead health states on the basis of annual probabilities of receiving vaccination, acquiring IPD, becoming disabled because of IPD, or dying because of IPD or other causes (Fig. 1). Annual mortality rates due to other causes were modeled on the basis of 2006 US mortality tables [11]. Given little data on the likelihood of disability with IPD, we used IPD meningitis rates as a proxy, understanding that not all meningitis leads to disability and that other forms of IPD can. We assumed that all IPD cases were hospitalized and did not first seek outpatient care, biasing the model against the vaccination program [2]. The only differences between the model arms were vaccination program costs and the probability of vaccination in model years 1 to 10.

Fig. 1.

The Markov state transition diagram. The only differences between the intervention and no-intervention arms of the model are the cost of the vaccination program and the probability of receiving pneumococcal vaccination in every Markov cycle.

IPD Incidence, Disability, and Mortality

Age-specific estimates of IPD incidence, disability (meningitis), mortality, vaccine serotype coverage, and the likelihood of immunocompromising conditions were obtained from 2007–2008 Active Bacterial Core surveillance data (Table 1). As IPD incidence—but not IPD case fatality—is known to vary by race, race-specific estimates of IPD incidence were incorporated [2,6–8]. African American IPD incidence was estimated by assuming that the proportion of IPD cases for each African American age cohort was the same as the proportion of IPD cases for each age cohort in the entire elderly population. This assumption was tested in sensitivity analyses in which IPD incidence was varied from 80% to 120% of the base-case value to examine model robustness when this assumption was relaxed. Lacking empirical data, we estimated IPD incidence in Hispanics on the basis of relative incidence rates of IPD in African American and Hispanic pediatric populations (relative risk 1.22:1) [7]. Because these are pediatric literature data, a secondary analysis was performed in which the relative IPD risk in these populations was varied from 80% to 120% of the base-case value, based on author estimates, to account for possible differences between pediatric and elderly cohorts. A population-weighted average IPD incidence was then estimated from the elderly African American and Hispanic populations on the basis of the relative size of these two populations (ratio 1.49:1) [12]. This IPD incidence estimate is in part a function of current pneumococcal vaccination uptake and thus likely underestimates IPD incidence when the theoretical absence of PPSV23 is modeled. To account for current pneumococcal vaccination effects on IPD incidence rates, elderly African American and Hispanic IPD rates were adjusted on the basis of data from a previous study suggesting that PPSV23 had led to IPD incidence reductions of 27.8, 13.5, 11.0, 1.7, and 3.4%, respectively, in the 65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85 years and older age cohorts across races (Table 1) [13]. We elected not to model changes in herd immunity for several reasons. First, the elderly IPD incidence rate has been stable from 2005 to 2010 [1,14]. Second, it is difficult to predict the impact of the recently introduced childhood 13-valent conjugate vaccine on the elderly IPD incidence rate and serotype epidemiology. In one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses, IPD incidence, IPD disability, IPD mortality, vaccine serotype coverage, and percentage of immunocompromised were varied across triangular distributions on the basis of maximum variation in values reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance network between 2003 and 2010 [1].

Table 1.

Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in the US elderly population, 2007–2008.

| Age cohorts (y)

|

Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65–69 | 70–79 | ≥80 | ||

| IPD cases per 100,000 per year in the general population (all races) | 25.9 | 33.9 | 60.1 | ABCs |

| African American population | 41.6 | 54.5 | 96.4 | Estimate*† |

| Hispanic population | 34.0 | 44.6 | 78.9 | Estimate*‡ |

| African American, Hispanic weighted average | 38.5 | 50.5 | 89.3 | Estimate*§ |

| IPD outcomes per 100,000 per year in the general population (all races) | ||||

| IPD meningitis | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.3 | ABCs |

| IPD death | 2.9 | 3.9 | 11.9 | ABCs |

| PPSV23 vaccine serotype coverage (all races) | 74.1% | 65.8% | 62.9% | ABCs |

| Population immunocompromised (all races) | 13.1% | 20.2% | 23.8% | ABCs |

ABCs, Active Bacterial Core surveillance network; PPSV23, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

Estimates of race-level IPD incidence do not include corrections for prior vaccination status explained in the text.

Based on ABCs population-level data on the incidence of IPD in the African American population.

Based on relative incidence of IPD in African American and Hispanic pediatric populations [7].

Based on incidence of IPD in African American and Hispanic elderly populations and relative population sizes [12].

Vaccine Effectiveness

Vaccine effectiveness was defined as a function of baseline vaccine effectiveness, declining effectiveness with time, vaccine serotype coverage, and the percentage of the population that was immunocompromised. PPSV23 was assumed effective only against IPD [4]. Declines in PPSV23 effectiveness over time and PPSV23 ineffectiveness in immunocompromised populations were modeled on the basis of expert panel estimates of PPSV23 effectiveness (Table 2) [15]. There is little evidence that PPSV23 effectiveness varies by race. To evaluate this parameter’s impact, PPSV23 effectiveness was varied ±10% in sensitivity analyses on the basis of author estimates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameter values for base-case and sensitivity analyses.

| Description | Base | Parameter range

|

Distribution | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Probabilities | |||||

| African American, proportion in minority cohort | 0.40 | Not varied | Not varied | Not varied | 12 |

| Hispanic, proportion in minority cohort | 0.60 | Not varied | Not varied | Not varied | 12 |

| IPD incidence | Table 1 | −6.6% | +6.6% | Triangular | 1 |

| IPD disability | Table 1 | −17.5% | +17.5% | Triangular | 1 |

| IPD mortality | Table 1 | −16.3% | +16.3% | Triangular | 1 |

| Percentage of elderly immunocompromised | Table 1 | −11.7% | +11.7% | Triangular | 1 |

| PPSV23 serotype coverage | Table 1 | −6.3% | +6.3% | Triangular | 1 |

| Vaccine effectiveness (year post vaccination)* | Triangular | 27 | |||

| Year 1 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.90 | ||

| Year 3 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.83 | ||

| Year 5 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.80 | ||

| Year 7 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.48 | ||

| Year 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | ||

| Year 15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | ||

| Change in vaccine effectiveness due to race | Base | −10% | +10% | Triangular | Estimate |

| Vaccination rate with no program (cumulative) | |||||

| Elderly African American population | 0.45 | Not varied | Not varied | Not varied | 5 |

| Elderly Hispanic population | 0.40 | Not varied | Not varied | Not varied | 5 |

| Vaccination rate with program (cumulative) | Figure 2 | Figure 2 | Figure 2 | Triangular | Estimate |

| Vaccine side effects† | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | Beta | 28 |

| Excess mortality due to disability (per year) | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | Triangular | 29 |

| Costs ($) | |||||

| Program, per targeted elder per year | 10 | 5 | 15 | Triangular | 9 |

| Pneumococcal vaccine and administration | 33.47 | 16.74 | 55.79 | Gamma | 29 |

| Treatment of vaccine side effects | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.75 | Gamma | Estimate |

| IPD | |||||

| Hospitalization without death | 27,357 | 25,224 | 30,093 | Gamma | 29 |

| Hospitalization with death | 37,688 | 33,919 | 41,458 | Gamma | 29 |

| Disability (annual) | 12,683 | 10,451 | 14,914 | Gamma | 30 |

| Durations | |||||

| Vaccine side effects (d) | 3 | 1 | 8 | Gamma | 28 |

| IPD hospitalization (d) | 12 | 9 | 15 | Gamma | 31 |

| Utilities | |||||

| One year of healthy life for >65-y-olds (QALY) | Uniform | 21, 32 | |||

| 65–70 y | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.81 | ||

| 70–75 y | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.79 | ||

| 75–80 y | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.75 | ||

| 80–85 y | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.68 | ||

| >85 y | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.56 | ||

| Vaccine side effects | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.99 | Uniform | 10, Estimate |

| IPD, hospitalized | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.25 | Uniform | 32 |

| IPD, disabled | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.60 | Uniform | 10, Estimate |

IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; PPSV23, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Expert panel estimates of PPSV23 effectiveness in the immunocompetent, well, 65-y-old cohort.

Vaccine side effects include mild redness, swelling, and soreness at the injection site.

Vaccination Program Effectiveness

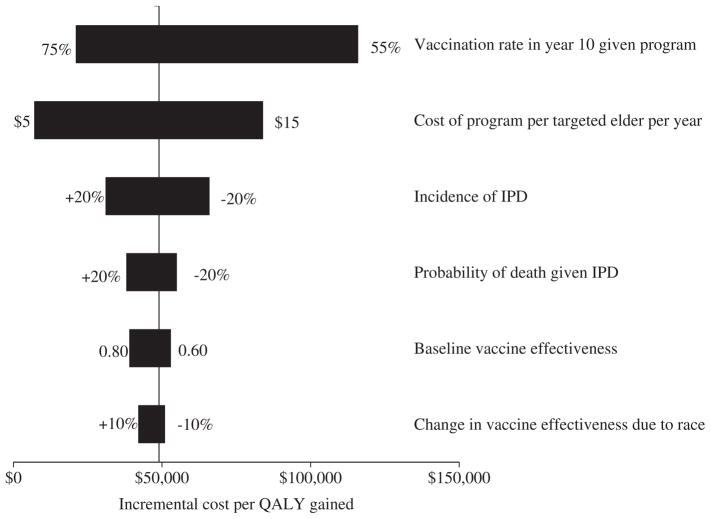

Based on the current percentage of elderly African Americans (45%) and Hispanics (40%) reporting having ever received PPSV23 in 2009 and the relative size of those populations, a population-weighted average of ever having received pneumococcal vaccination of 43% was calculated [5,12]. In the no-intervention arm, 43% of the cohort was vaccinated in year 1 with no incremental increases in years 2 to 10, thus incorporating the entire reported vaccination uptake for the minority population aged 65 years and older at age 65 years. This concentrates the benefits of vaccination in the no-intervention arm to early in the model time frame, biasing against the intervention arm because of the effects of discounting and age-related decreases in vaccine effectiveness. With the intervention program, 51% of the cohort was vaccinated in year 1 and further incremental increases in annual vaccination over years 2 to 10 resulted in 65% of the population receiving PPSV23 by year 10, equaling the current pneumococcal vaccination rate seen in the elderly Caucasian population (Fig. 2) [5]. In the base-case analysis, it was assumed that program-associated increases in vaccination rates were greater earlier in the program and decreased in later years to reflect decreasing program impact because of response fatigue and a ceiling effect at higher vaccination rates (Fig. 2). This rapid increase in vaccination rates from 43% to 62% in the program’s first 5 years is reasonable given evidence suggesting that multimodal interventions result in a median 16% increase in vaccination rates over a single year [16]. The final vaccination rate achieved with the program (65%) is well within the range of achievable pneumococcal vaccination rates reported elsewhere for the elderly African American (73%) and Hispanic (76%) populations [17]. In a secondary analysis, we evaluated the assumption that program-associated gains in vaccination rates were linear, still assuming that a vaccination rate of 65% was reached in year 10. When the program ended at year 10, the incremental vaccination rate dropped immediately to zero, with no residual effect of the program, possibly biasing results against the program. In sensitivity analyses to establish a range of possible improvements in vaccination rates, minimum and maximum possible vaccination rates at 10 years of 55% and 75%, respectively, were examined, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative pneumococcal vaccination rates used in the model. Three scenarios are presented here, each one assuming that increases in the vaccination rate were driven by the deployment of a national program to decrease racial disparities in pneumococcal vaccination rates. Pneumococcal vaccination rates in Caucasians aged 65 years and older are 65%. PPSV23, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

Costs and Effectiveness

The following costs were included in the model: vaccine program promotion, vaccine dose and administration, vaccine side effect treatment, IPD hospitalization with and without death, and annual disability due to IPD (Table 2). No differences in outpatient care costs between patients who did and did not acquire IPD were modeled, which could bias against the intervention. Costs were mainly drawn from the published literature and 2006 Nationwide Inpatient Sample data. To estimate the costs of a program to decrease pneumococcal vaccination disparities, conservative costs from our previous work on the cost-effectiveness of a similar national vaccination intervention program to ameliorate disparities in influenza vaccination were used [9]. Briefly, three cost scenarios for the intervention were assumed: $5, $10 (base case), and $15 per targeted minority elder per year, regardless of previous vaccination status. These estimates were based on previous research suggesting that broad strategies to increase vaccination rates that are feasible on a national level—patient reminder interventions, standing order implementations, or public health education—would individually be unlikely to cost more than $5 per targeted minority elder per year [18–20]. Programs using multiple strategies to increase vaccination rates are more effective than single-component strategies [16]. Thus, in the base-case analysis, it was assumed that the vaccination intervention program deployed two discrete strategies to increase the minority elder vaccination rate, at a cost of $5 per targeted living minority elder per year for each strategy, resulting in a cost of $10 per targeted minority elder per year. These program costs are conservative, because they are allocated to every living minority elder on an annual basis regardless of prior vaccination status and were chosen to bias results against the intervention. All costs were kept constant except for intervention program costs, which were increased 3% annually. All costs are in 2011 dollars.

Effectiveness was measured in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), assuming that QALYs were time spent in a particular health state multiplied by the utility of that state, with utilities ranging from 1 (perfect health) to 0 (death) (Table 2). Utility values are defined by activity limitation and perceived health and are based on 1990 data from the National Health Interview Survey, a sample of noninstitutionalized residents in 50,000 US households [21]. Given the absence of available health status data from institutionalized residents in correctional facilities, nursing homes, and long-term care facilities, assumptions were made regarding activity limitation and perceived health to estimate utility weights for these populations [21]. All cost and effectiveness values were discounted at 3% per year in the base case and 3% to 5% in a secondary analysis [10].

Analyses

A cost-effectiveness analysis was performed to determine the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of the vaccination program relative to no program. Subsequently, one-way sensitivity analyses were examined to identify parameters having the greatest impact on results. Based on preliminary analyses suggesting that the vaccination program cost and vaccination rate achieved in year 10 had a substantial impact on the ICER, these parameters were varied in a two-way sensitivity analysis to estimate threshold values for cost-effectiveness. For one-way and two-way sensitivity analyses, threshold analyses were performed to determine parameter values that caused the program ICER to cross $50,000 and $100,000 per QALY gained thresholds. Three probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed for the base-, low-, and high-cost scenarios, with all parameter values simultaneously varied over distributions (Table 2). To account for both parameter uncertainty and population heterogeneity in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, we stratified the cohort by race, separately varying the probability of receiving vaccination with the intervention in elderly African American and Hispanic populations. For each parameter, the listed range and distribution mirrors the 95% confidence interval for that parameter, based on data from the reference or from approximations for ranges. Although $50,000 per QALY gained has been frequently used as a cost-effectiveness criterion, recent research suggests that a threshold of $100,000 per QALY is reasonable [22]. Both criteria were used as lower and upper thresholds for cost-effectiveness. This study was completed between October 2011 and February 2012.

Results

Base-Case Analysis

In the base-case analysis, the national vaccination intervention program to eliminate disparities in pneumococcal vaccination rate among elderly minority populations was both more costly ($238 vs. $185) and more effective (9.71249 vs. 9.71131 QALYs gained) than no program, costing $45,161 per QALY gained. Over its 10-year duration, in the approximately 396,000 in the 65-year-old minority birth cohort, the intervention prevented 853 IPD cases and 134 IPD deaths at a cost of $22.7 million, or $26,626 per IPD case avoided and $169,027 per IPD death avoided. In the secondary analysis, in which constant incremental gains in vaccination rate over the 10-year program period were assumed, the program cost $52,432 per QALY gained.

One-Way and Two-Way Sensitivity Analyses

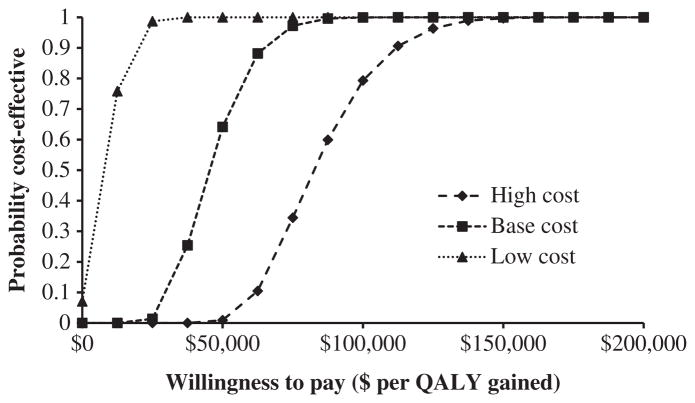

In the one-way sensitivity analysis, six individual parameters resulted in a 10% or more change in the ICER of the vaccination intervention program relative to no program (Fig. 3). The two parameters whose variation most affected the ICER were the vaccination rate in program year 10 ($21,000–$116,000 per QALY) and program cost ($7,000–$84,000 per QALY). For these two variables, the ICER was less than $50,000 per QALY when the year 10 vaccination rate was more than 64.2% or the program cost was less than $10.63 per person, and was less than $100,000 per QALY when the vaccination rate was more than 56.4% or the program cost was less than $17.12 per person. In the two-way sensitivity analysis varying both program costs and the year 10 vaccination rate, the ICER was less than $100,000 per QALY when the program cost less than $8.60 per targeted elder per year and resulted in a year 10 vaccination rate of more than 62.8%. When varying vaccination program costs, the ICER varied from 80% to 120% of its original value when the vaccination rate achieved in year 10 of the program varied between 64.9% and 66.2% in the low-cost scenario, 63.6% to 67.9% in the base-case scenario, and 63.3% to 68.5% in the high-cost scenario. In secondary analyses, when the relative incidence of IPD in the elderly African American and Hispanic populations was varied from 80% to 120% of the base case, the ICER varied from $38,463 to $50,372 per QALY gained. When the discount rate was increased from 3% to 5%, the ICER of the vaccination program increased from $45,161 to $66,270 per QALY gained.

Fig. 3.

One-way sensitivity analysis. The six parameters presented here, when varied individually across their distributions, caused a 10% or more change in the ICER of the vaccination intervention program relative to no program. ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

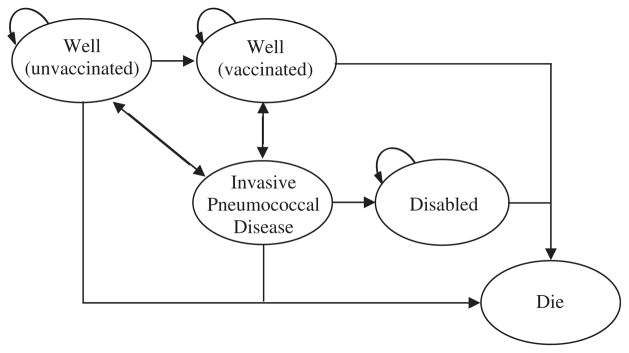

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis

Results from the probabilistic sensitivity analysis examining three different cost scenarios are presented in Figure 4. Compared with no program, the vaccination program had a higher probability of being cost-effective when program costs were lower and the societal willingness-to-pay threshold was higher. At a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained, the probability of the vaccination intervention program being cost-effective under the base-, low-, and high-cost scenarios was, respectively, 64%, 100%, and 1%. At a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per QALY gained, the probability of the program being cost-effective under the base-, low-, and high-cost scenarios was, respectively, 100%, 100%, and 79%.

Fig. 4.

Acceptability curves from probabilistic sensitivity analyses. Depiction of the likelihood of a pneumococcal vaccination intervention program being cost-effective at different costs and willingness-to-pay thresholds. QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Conclusions

This exploratory study outlines the parameters for a cost-effective vaccination program designed to eliminate known disparities in pneumococcal vaccination among elderly minority groups and suggests that such a program would be cost-effective in the base-case scenario ($45,161 per QALY gained). Using conservative assumptions regarding the cost and effectiveness of such a vaccination program, the program was cost-effective by conventional criteria (<$50,000 per QALY gained) and became cost-prohibitive (>$100,000 per QALY gained) only at relatively unlikely values for the vaccination rate achieved in year 10 of the program (<56.4%, compared with 43% prior to year 1 of the program). This study suggests that a pneumococcal vaccination program directed at elder minorities is moderately (64%) and highly (100%) likely to be cost-effective under more and less conservative cost-effectiveness thresholds, respectively.

This study adds to the wealth of research supporting the cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination in elderly populations and to more recent studies suggesting that national programs to promote vaccination in elderly populations, in general, and in elderly minority populations, more specifically, are likely to be cost-effective [9,20]. In this analysis, the ICER of the minority pneumococcal vaccination program ($45,161 per QALY gained) was comparable to the ICER of a similar minority influenza vaccination program ($48,617 per QALY gained) reported in our previous work, providing further evidence that vaccination programs aimed at reducing racial disparities in vaccination rates are cost-effective [9]. This similarity in the ICERs of influenza and pneumococcal minority elder vaccination programs is likely the result of counterbalancing differences in disease incidence and cost. Influenza is more common but less costly, whereas IPD is less common but more costly. Beyond suggesting that a pneumococcal vaccination intervention program is likely to be cost-effective, this study also provides broad guidelines for cost thresholds required to maintain a cost-effective program.

Findings supporting a minority vaccination intervention program are particularly important in the context of the substantially higher IPD incidence seen in many minority groups, particularly the African American population, in which IPD incidence has been reported to be greater than twice that seen in Caucasians [2]. The reasons for this racial difference are likely multifactorial. Disadvantaged racial groups have higher rates of substance abuse, including tobacco and alcohol, which are associated with increased IPD [23]. HIV incidence is also higher is some minority groups, and HIV is associated with increased IPD incidence [24]. Race also influences crowding and poverty, further complicating potential IPD risk factors [25]. Hence, there are many potential approaches for interventions to reduce racial disparities in IPD incidence.

Several aspects of this study are worthy of mention. First, the model incorporates conservative assumptions regarding the cost and effectiveness of the vaccination intervention program to bias the model against it. We assumed that the program deployed two independent strategies to increase vaccination rates, cost $10 per targeted minority elder per year regardless of prior pneumococcal vaccination status, and increased the cumulative minority elder vaccination rate to 65% to match the elderly Caucasian vaccination rate by program year 10. Second, no potential ancillary benefits of the vaccination intervention program, such as concomitantly improved vaccination rates in the elderly Caucasian population, were modeled. Depending on the strategies deployed, it is possible that a vaccination intervention program targeted toward minority elders would also have beneficial effects for all elders. Third, only with relatively large program costs and small gains in vaccination rates did the program become cost-prohibitive (ICER >$100,000 per QALY gained).

Several important limitations bear mentioning. First, the model considered a single birth cohort of minority elders age 65 years and did not consider multiple birth cohorts age 65 years or more. Thus, it is not possible to directly generalize our findings to the entire elderly minority population. Given that IPD incidence and case fatality increases after age 75 years, however, this modeling choice is likely to bias the model against the vaccination program. Second, declines in vaccine effectiveness with time were based on expert opinion due to the absence of rigorous empirical data. This parameter, however, was varied widely in sensitivity analyses and was found to have a relatively small impact (Fig. 3). Third, because of few data on IPD incidence in the elderly Hispanic population, IPD incidence was estimated on the basis of relative IPD incidence in pediatric African American and Hispanic populations [7]. Published epidemiologic data, however, do not suggest large differences in IPD disease burden across age cohorts between African American, Caucasian, and “other” populations, and sensitivity analyses suggest a modest impact of this parameter on the ICER [2]. Fourth, we assumed that the elderly minority population achieves a vaccination rate that is equivalent to the elderly Caucasian population rate (65%) by program year 10. If elderly minority populations, however, are less responsive than elderly Caucasian populations to strategies aimed at improving vaccination rates, the program may be less cost-effective than currently assessed. Given historical distrust of health care providers and differences in health care–seeking behavior reported among minority populations, this is not an unreasonable concern [26]. From 2000 to 2009, however, absolute increases in pneumococcal vaccination rates in elderly African Americans and Hispanics (13.9% and 9.7%, respectively) outpaced increases in vaccination rates in elderly Caucasians (8.1%) [5]. Furthermore, outcomes from an urban network of 11 federally qualified urban health centers in Denver have shown pneumococcal vaccination rates in African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian populations of 73%, 76%, and 61%, respectively, suggesting that higher pneumococcal vaccination rates in elderly minority populations are achievable [17].

This analysis suggests that even with conservative assumptions, a national program to reduce disparities in pneumococcal vaccination rates among elderly minority groups would be cost-effective. This work has important policy implications, suggesting that up to $10.63 per targeted elder per year can be spent on a vaccination program targeted at elder minorities and that this program would remain cost-effective at the $50,000 per QALY threshold provided there are reasonable gains in the pneumococcal vaccination rate. This analysis will serve as a basis for future evaluation of specific vaccination program strategies to increase the vaccination rate among minority elders.

Acknowledgments

Source of financial support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant no. R01AI076256) and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Clinical Scientist Training Program.

References

- 1.Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003 to 2010. [Accessed January 5, 2013]. Emerging Infections Program Network, Streptococcus pneumoniae. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/surv-reports.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson KA, Baughman W, Rothrock G, et al. Epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in the United States, 1995–1998. JAMA. 2001;285:1729–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro ED, Berg AT, Austrian R, et al. The protective efficacy of polyvalent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1453–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moberly SA, Holden J, Tatham DP, Andrews RM. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD000422. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000422.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed February 1, 2012];National Immunization Survey, 2009 Adult Vaccination Coverage. 2009 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nhis/downloads/2009-nhis-tables.xls.

- 6.Chen F, Breiman R, Farley M, et al. Geocoding and linking data from population-based surveillance and the US census to evaluate the impact of median household income on the epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:1212–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu K, Pelton S, Karumuri S, et al. Population-based surveillance for childhood invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:17–23. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000148891.32134.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortese MM, Wolff M, Almedio-Hill J, et al. High incidence rates of invasive pneumococcal disease in the White Mountain Apache population. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2277–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaelidis CI, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Smith KJ. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of a national program to eliminate disparities in influenza vaccination rates among elderly minority groups. Vaccine. 2011;29:3525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, editors. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arias E. United States life tables, 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(21):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed February 1, 2012];2009 resident population by race. Available from: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0010.pdf.

- 13.Fry AM, Zell ER, Schuchat A, et al. Comparing potential benefits of new pneumococcal vaccines with the current polysaccharide vaccine in the elderly. Vaccine. 2002;21:303–11. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of the conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:32–41. doi: 10.1086/648593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith KJ, Zimmerman RK, Lin CJ, et al. Alternative strategies for adult pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Vaccine. 2008;26:1420–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:97–140. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appel A, Everhart R, Mehler PS, MacKenzie TD. Lack of ethnic disparities in adult immunization rates among underserved older patients in an urban public health system. Med Care. 2006;44:1054–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228017.83672.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank JW, McMurray L, Henderson M. Influenza vaccination in the elderly, 2: the economics of sending reminder letters. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132:516–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middleton DB, Lin CJ, Smith KJ, et al. Economic evaluation of standing order programs for pneumococcal vaccination of hospitalized elderly patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:385–94. doi: 10.1086/587155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel MS, Davis MM. Could a federal program to promote influenza vaccination among elders be cost-effective? Prev Med. 2006;42:240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson P, Wilson R, Shannon I. Statistical notes no 7: years of healthy life. Healthy People. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics 2000; Apr, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braithwaite RS, Meltzer DO, King JT, Jr, et al. What does the value of modern medicine say about the $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year decision rule? Med Care. 2008;46:349–56. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815c31a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Farley MM, et al. Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 200;341:681–689. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003093421002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klemets P, Lyytikäinen O, Ruutu P, et al. Invasive pneumococcal infections among persons with and without underlying medical conditions: implications for underlying medical conditions: implications for prevention strategies. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenmakers MCJ, Fleer A, Aerts PC, et al. Risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease. Rev Med Microbiol. 2002;13:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith KJ, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Roberts MS. Age, revaccination, and tolerance effects on pneumococcal vaccination strategies in the elderly: a cost effectiveness analysis. Vaccine. 2009;27:3159–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson LA, Benson P, Butler JC, et al. Safety of revaccination with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. JAMA. 1999;281:243–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith KJ, Lee BY, Nowalk MP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dual influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in 50-year-olds. Vaccine. 2010;28:7620–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson WL, Armour BS, Finkelstein EA, Weiner JM. Estimates of state-level health-care expenditures associated with disability. Publ Health Rep. 2010;124:44–51. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evers SM, Ament AJ, Colombo GL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination for prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly: an update for 10 Western European countries. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:531–40. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0327-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sisk JE, Whang W, Butler JC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination against invasive pneumococcal disease among people 50 through 64 years of age: role of comorbid conditions and race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:960–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-12-200306170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]