Abstract

A polymorphism on the MUC5B promoter (rs35705950) has been associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) but not with systemic sclerosis (SSc) with interstitial lung disease (ILD). We genotyped the MUC5B promoter in the first 142 patients of the French national prospective cohort of IPF, in 981 French patients with SSc (346 ILD), 598 Italian patients with SSc (207 ILD), 1383 French controls and 494 Italian controls. A meta-analysis was performed including all American data available. The T risk allele was present in 41.9% of the IPF patients, 10.8% of the controls (P = 2×10–44), OR 6.3 [4.6–8.7] for heterozygous patients and OR 21.7 [10.4–45.3] for homozygous patients. Prevalence of the T allele was not modified according to age, gender, smoking in IPF patients. However, none of the black patients with IPF presented the T allele. The prevalence of the T risk allele was similar between French (10%) and Italian (12%) cohorts of SSc whatever the presence of an ILD (11.1% and 13.5%, respectively). Meta-analysis confirmed the similarity between French, Italian and American cohorts of IPF or SSc-ILD. This study confirms 1) an association between the T allele risk and IPF, 2) an absence of association with SSc-ILD, suggesting different pathophysiology.

Introduction

Lung fibrosis is a common trait of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and systemic sclerosis (SSc) with interstitial lung disease (ILD). Indeed, ILD is present in almost 40% of the patient with SSc and is the major cause of death during SSc [1]. However the most common histological and radiological pattern observed in SSc-ILD is non specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), whereas the pattern associated with IPF is usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) [2]. There is still a debate concerning the pathophysiology of NSIP and UIP, there is evidence that both patterns share aetiologies and can occur in the same context.

Both IPF and SSc are considered as genetic complex diseases, and occur in genetically predisposed individuals who have experienced certain environmental or stochastic stimuli [3]. An association between a functional polymorphism located in the putative promoter region of the MUC5B gene (rs35705950) and sporadic and familial IPF has been recently identified in 3 American cohorts including 916 patients [4], [5] and was recently confirmed in 2 genome wide association studies [6], [7]. A candidate gene association study which investigated MUC5B rs35705950 in 109 individuals having SSc-ILD suggested a lack of association [8]. Moreover a recent gene association study in England confirmed an association with IPF (n = 110) and a lack of association with SSc-ILD (n = 440) or sarcoidosis (n = 180) [9]. To date, no information is available regarding the association between MUC5B rs35705950 and IPF or SSc-ILD in French or Italian populations. These findings prompted us to test an association between the MUC5B rs35705950 variant and i) IPF in the French population, and ii) SSc-related ILD in two large European Caucasian populations. We then performed a meta-analysis of the American and European data in IPF and SSc.

Methods

Study populations

IPF populations

A French prospective and multicentric cohort of recently diagnosed IPF (the COFI cohort) was established starting in 2008. Inclusion criteria comprised a diagnosis of IPF based upon either surgical biopsy or a characteristic CT scan pattern according to the 2001 ATS/ERS consensus [10]. The first imaging allowing the diagnosis of IPF had to date back to a maximum of 9 months prior to inclusion. All demographic, comorbidity, clinical and functional data were prospectively and serially recorded.

SSc populations and controls

We studied two European cohorts of patients with SSc and their associated controls. The French cohort included 981 SSc patients and 1229 controls coming from the French network as previously described [11]. The replication step came from Italy included 598 SSc patients and 494 controls [11]. Of note all SSc patients and controls were Caucasian. Patients were classified according to LeRoy's cutaneous subtypes [12]. SSc patients were tested for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) using indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) and HEp-2 cells as antigen substrate (Antibodies Inc., Davis, CA). Specific SSc antibodies were systematically assessed; anti-centromere antibodies (ACAs) were determined by their distinctive IIF pattern on HEp-2 cells. Anti-topoisomerase I antibodies (TOPO) were determined by counter immuno-electrophoresis.

ILD was defined as the presence of ground glass opacity and/or reticular opacities in a peripheral distribution on chest CT scan, however a classification according to the UIP or NSIP pattern was not performed. CT scan was not available for 99 and 7 patients of the French and Italian cohorts respectively.

Local institutional review board approval was obtained for every study subject and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (Ethical Committee of Firenze, Comité pour la Protection des Personnes Ile de France X, Aulnay sous Bois).

Genotyping

All the subjects were genotyped for the MUC5B rs35705950 SNP using a competitive allele specific PCR system (Kaspar genotyping, Kbioscience, Hoddeston, UK) and Taqman SNP genotyping assay-allelic discrimination method (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA) as previously described [11]. The average genotype completeness was 99% for SSc and IPF and controls samples for the SNP investigated. The accuracy was >99%, according to duplicate genotyping of 10% of all samples.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the R computer package software (version 2.10.1). The level of significance for all the tests corresponds to a type-I error-rate α = 5%. Tests for conformity to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) were performed using a standard χ 2 test (1 degree of freedom) to test for differences between observed and expected genotype distributions based on control population allele frequencies.

Individual association analyses of the MUC5B rs35705950 SNP with IPF or SSc were performed by comparing cases and controls with a Fisher's exact or Chi2 test on genotypes. Blacks individuals with IPF were excluded from analysis as our controls were all Caucasians. The corresponding ORs were assessed using a standard logistic regression analysis with the most frequent homozygous genotype in the control population taken as the reference. The same procedure was applied in subgroups stratified according to SSc phenotypes, compared to controls.

Meta-analysis of rs35705950

We performed a systematic review and the meta-analysis of all data published up to December 2012. We searched Medline via PubMed with the terms “MUC5B” for articles published in English that provided 3 relevant articles. We did not find other articles with hand-searched reference lists of clinically relevant articles. We contacted the corresponding author that provided us the full data. We therefore fulfilled the PRISMA guidelines.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

The meta-analysis included the data obtained in the French IPF population from this study, and the data from American IPF patients coming from Denver (n = 488), Chicago (n = 95) and Pittsburgh (n = 246), previously published [4], [5].

Systemic sclerosis

The meta-analysis included data obtained in the French and Italian populations from this study, and data from American population of SSc patients from Northwestern Scleroderma Program (n = 231) and controls from Denver (n = 322), Chicago (n = 636) and Pittsburgh (n = 166) [4], [5], [8].

The combined data including the 4 populations of IPF, 3 populations of SSc and 5 populations of controls were analyzed by calculation of homogeneity of ORs among the cohorts using the Breslow-Day and Woolf Q methods, and by calculation of the pooled ORs under a fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel metaanalysis) or random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird) when necessary and assessed by logistic regression analysis genetic effects under 3 modes of inheritance: additive, dominant, and recessive.

Results

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. The genotypic frequencies for rs35705950 were consistent with in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the controls populations.

Table 1. Characteristics of the French IPF patients.

| French Population N 142 | |

| Female | 18% |

| Age, years | 69.8±8.9 |

| Smoker (active) | 68% (4%) |

| Ethnic status | |

| Caucasian | |

| European | 82% |

| North African | 14% |

| Black | 4% |

| Pulmonary Fonction | |

| FVC (%) | 76±20 |

| DLCO (%) | 47±19 |

Data are expressed as % or mean± SD. IPF Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Case-control analysis shows association of the rs35705950 SNP with IPF (Table 2). The minor-allele frequency was 41.9% in the IPF cohort compared to 10.8% in controls (P = 2.9×10−44). Odds ratios for IPF in subjects who were heterozygous and homozygous for the minor allele of rs35705950 were 6.3 (95% confidence interval, [CI], 4.6 to 8.7) and 21.7 (95% CI, 10.4 to 45.3) respectively.

Table 2. Association between the MUC5B rs35705950 polymorphism and IPF, SSc and SSC-ILD in the European population.

| TT (%) | GT (%) | GG (%) | T (%) | P | OR [95% CI] | ||

| French populations | |||||||

| IPF n = 142 | 11.90 | 53.57 | 34.52 | 38.69 | GT TT | 4×10 −29 9×10 −29 | 6.4[4.5–9]19[9–36] |

| SSc n = 981 | 1.22 | 17.53 | 81.24 | 9.99 | G GG GT | 0.36 0.61 0.42 | 0.91[0.76–1.11]0.83[0.40–1.71]0.92[0.74–1.14] |

| SSc-ILD+ n = 346 | 1.39 | 19.50 | 79.11 | 11.14 | G GG GT | 0.79 0.95 0.74 | 1.04[0.79–1.34]0.97[0.36–2.61]1.05[0.78–1.41] |

| SSc-ILD- n = 536 | 0.93 | 17.72 | 81.34 | 9.79 | G GG GT | 0.36 0.63 0.93 | 0.89[0.71–1.13]0.63[0.24–1.70]0.93[0.72–1.20] |

| Controls n = 1383 | 1.45 | 18.73 | 79.83 | 10.81 | |||

| Italian populations | |||||||

| SSc n = 598 | 1.34 | 21.40 | 77.26 | 12.04 | G GG GT | 0.82 0.54 0.55 | 1.03[0.79–1.34]0.75[0.29–1.95]1.09[0.81–1.47] |

| SSc-ILD+ n = 207 | 1.45 | 24.15 | 74.40 | 13.53 | G GG GT | 0.35 0.79 0.21 | 1.17[0.84–1.65]0.84[0.22–3.14]1.28[0.87–1.82] |

| SSc-ILD-n = 384 | 1.30 | 19.79 | 78.91 | 9.79 | G GGGT | 0.72 0.54 0.95 | 0.9[0.71–1.13]0.71[0.24–1.70]0.99[0.72–1.20] |

| Controls n = 494 | 1.82 | 19.84 | 78.34 | 11.74 | |||

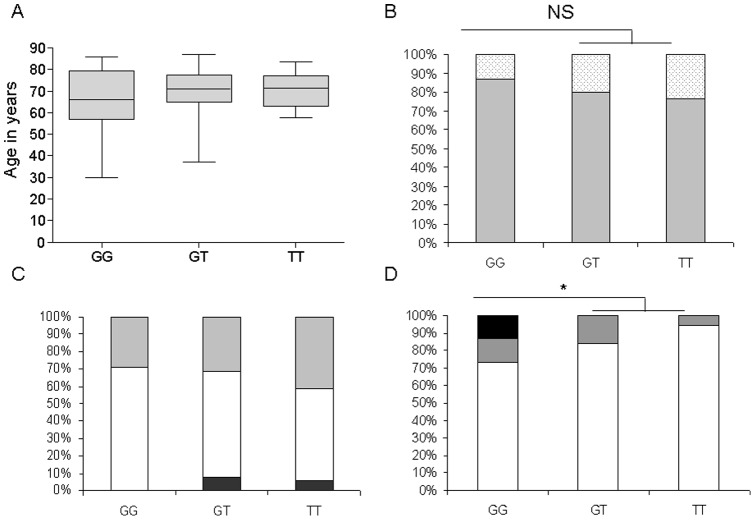

In the IPF cohort, the distribution of homozygous and heterozygous patients was not different according to gender, age, smoking habitus, pulmonary function test or presence of a cancer at diagnosis, even in subgroup analysis according to gender (Figure 1). The MUC5B rs35705950 IPF risk allele was not detected in the French black individuals with IPF (P = 0.0008).

Figure 1. Distribution of clinical characteristic according to the MUC5B genotype.

(A) Distribution of age according to genotype. The centre line of the box denotes the mean, the extremes of the box the interquartile range and the bars the highest and lowest values. (B) Distribution of the gender according to the genotype. Percentage of men is represented in grey; percentage of women is represented in white with black dots. NS non significant. (C) Distribution of the smoking status according to the genotype. Percentage of never smokers is represented in grey, percentage of past smokers is represented in white, and percentage of active smokers is represented in black. (D) Distribution of the ethnic status according to the genotype. Percentage of European is represented in white, percentage of North African is represented in grey, and percentage of black patients is represented in dark. * P = 0.0008.

Systemic sclerosis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Characteristics of the SSc patients in the 2 investigated European populations.

| French Population n = 981 | Italian Population n = 598 | |

| Female (%) | 83.6 | 86.1 |

| Mean age, years | 57.2±12.8 | 53.6±10.9 |

| Mean disease duration, years | 10.9±8.7 | 11.5±8.9 |

| Limited cutaneous subtype (%) | 64.5 | 69.9 |

| Anti-Topo I positive patients (%) | 27.3 | 29.9 |

| ACA positive patients (%) | 40.3 | 42.1 |

| ILD on CT scan (%) | 35.2% | 34.6% |

Anti-Topo I: anti-topoisomerase I antibodies; ACA: anti-centromere antibodies; ILD interstitial lung disease. Data are expressed as % or mean ± SD. SSc systemic sclerosis. ILD Interstitial lung disease.

Regarding the French population of SSc, no allelic association was detected between the MUC5B rs35705950 SNP and the overall disease: the minor allele was found in 10% of SSc individuals compared to 10.8% in controls (P = 0.36). We failed to detect any statistical difference of the genotypes distribution between SSc patients with and without ILD and the controls in the French population (Table 2). Similar allelic and genotypic frequencies were observed in the Italian population, the lack of association between SSc with or without ILD and MUC5B rs35705950 being replicated (Table 2). In the SSc cohorts, the distribution of homozygous and heterozygous patients was not different according to gender.

Meta-analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Characteristics of the populations investigated for meta-analysis.

| IPF | Controls for IPF | SSc | SSc-ILD+ | Controls for SSc | |

| N | 975 | 2353 | 1810 | 662 | 2045 |

| Female (%) | 26.8 | 55.5* | 89.9 | 83.6 | 62.4* |

| Caucasian (%) | 100 | 100 | na | na | 100 |

| Mean age, years | 68.7 | 48.0* | 54.5 | 56.5 | 45.2* |

| FVC (%) | 66.9* | na | 85.5* | 82.4* | NA |

| DLCO (%) | 45.9* | na | 65.1* | 54.9* | NA |

some data may be missing but data expressed represent always more than 2/3 of the populations. na not available.

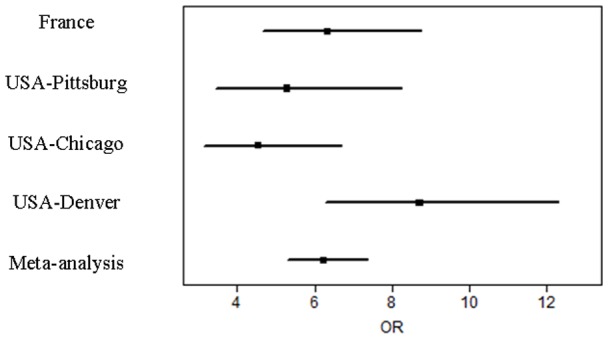

Remarkably, the genotypic frequencies were very similar in the French and American populations of IPF and controls. The meta-analysis of the 4 IPF populations evidenced a strong association between MUC5B rs35705950 T allele and IPF: P = 5×10−105, OR 6.2 95% CI[5.3–7.3] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of the MUC5B rs35705950 T allele risk in the three American cohorts and the French cohort of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Forrest plots of the meta-analysis of the association of the MUC5B rs35705950 T polymorphism and IPF. Bars represent the 95% interval.

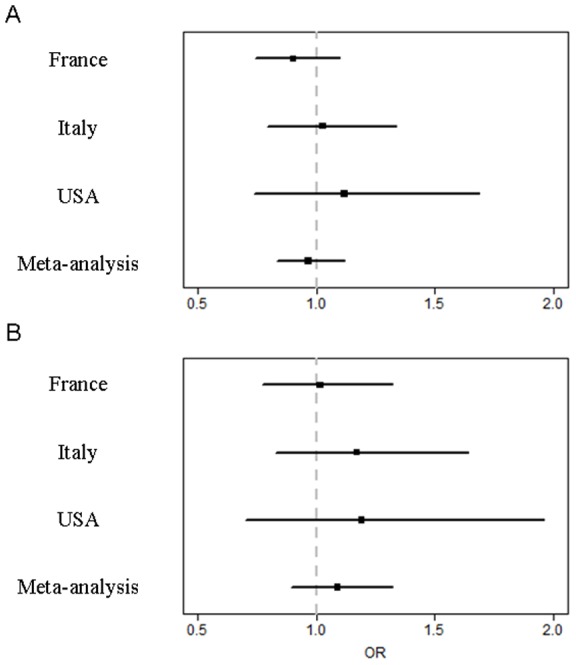

The genotypic frequencies of the herein study were very similar to that observed in the North American populations of SSc and SSc-ILD. The meta-analysis of the 3 SSc populations confirmed the absence of association between MUC5B rs35705950 T allele and SSc whatever the presence of an ILD, OR 0.97 (95% CI, 0.84 to 1.12), P = 0.64, for the association with SSc, and OR 1.09 (95% CI, 0.9 to 1.32), P = 0.38, for the association with SSc-ILD (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of the MUC5B rs35705950 T allele risk in the two European (French and Italian) cohorts and the American cohort of systemic sclerosis (SSc).

Forrest plots of the meta-analysis of the association of the MUC5B rs35705950 T polymorphism and (A) all SSc and (B) SSc with interstitial lung disease. Bars represent the 95% interval.

Discussion

In this study, we confirm in European populations an association between the MUC5B rs35705950 T allele and IPF and a lack of association with SSc related ILD. Despite a relative low number of IPF patients included, the meta-analysis provides a definitive conclusion about this association in Caucasian population. Interestingly, we observed that this polymorphism was absent in the six black patients with IPF.

Our meta-analysis provides a more accurate evaluation of the IPF risk associated with the T allele in Caucasian population. Remarkably the prevalence of the T allele risk in the cohorts of controls, SSc, SSc-ILD or IPF was almost similar in every population, including the English cohorts [9]. Indeed these cohorts are large and probably representative of the entire Caucasian population.

The Odd Ratio for IPF in heterozygotous carriers of the T allele is 6, whereas almost 10% of the control population presents with the T allele. The exact role of this polymorphism in IPF pathophysiology remains to be determined. Seibold et al. suggested that rs35705950 was functional [4]. Indeed, in unaffected subjects, the presence of the T allele was associated with a 37 fold increased expression of MUC5B gene in the lung. Furthermore, MUC5B expression was increased 14-fold in the lung in IPF patients when compared to controls. MUC5B is the dominant gel-forming mucin in the normal distal airway epithelium. Plantier and colleagues demonstrated by immunohistochemistry that, in contrast to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MUC5B was the predominant mucin detected in the abnormal mucus cells observed in the honeycombing areas of the fibrotic lung in patients with IPF [13]. This result was confirmed by Seibold and coll. [14]. Interestingly a trend was observed by Stock and colleagues between the MUC5B variant and slower decline in forced vital capacity, whereas no difference was evidenced in this cohort regarding age or severity at diagnosis between carriers or non carriers of the T allele risk [9]. Some have suggested that a therapy targeting MUC5B transcriptional activity should be evaluated in IPF [15]. The association between increased expression of MUC5B and IPF suggest that MUC5B may have a direct role in the pathogenesis of IPF. MUC5B may interfere with the normal repair process of the alveolar epithelium. For instance, MUC5B overexpression leads to an aggressive behavior of breast cancer MCF7 cells with increased proliferation and invasion in vitro, although the mechanisms involved are unknown [16]. One may speculate whether MUC5B overexpression stimulates a fibroproliferative response, or associates with abnormal mucosal defences to exogenous injury. Very recently, the MUC5B rs35705950 T allele has been shown to be associated with better survival among patients with IPF [17]. Further studies are clearly needed to better understand this elective link between MUC5B overexpression and IPF and the absence of link with other fibrotic lung diseases.

Our meta-analysis clearly suggests that the T allele is not associated with an increase risk of SSc or ILD in SSc in the Caucasian population. This is a very important result as it may shed some light on specific lung fibrotic process in SSc. The radiological and pathological pattern in IPF is UIP. In SSc, different patterns have been described but the prominent pattern is NSIP [2], [18], [19]. To date, the SSc-ILD pathogenesis remains poorly understood. If the exact genetic contribution to SSc-ILD remains unknown, a population-based study provided evidence for the heritability of ILD in SSc, first-, third-, and fourth-degree relatives of individuals with SSc having significantly elevated relative risks for ILD [20]. In line with this, it has been previously identified that some of the SSc risk variants, such as IRF5 rs20046640, STAT4 rs7574865 and NLRP1 rs8182352 susceptibility alleles, contribute to a disease-specific phenotype, notably SSc-ILD [11], [21], [22]. The lack of an association between the MUC5B rs35705950 T allele and SSc related ILD suggest that this polymorphism does not associate with lung fibrosis in general, but might be specific for either IPF or UIP. Evaluating the prevalence of MUC5B polymorphism in large cohorts of idiopathic or non-idiopathic ILD may improve our understanding of the pathophysiology of these diseases.

Our IPF population included only 6 black patients with IPF; the MUC5B polymorphism was absent in all of them. There is paucity of data regarding prevalence of IPF in black populations. In the 3 American cohorts of IPF evaluating the prevalence of MUC5B polymorphism, all subjects were white [4], [5]. Nathan and al. reported a 13.8% prevalence of black in their IPF cohort from Fairfax [23], whereas Swigris and al. recently reported twice less IPF and a decreased risk of death from IPF in black descendents [24]. Further studies including a re-sequencing of MUC5B in other populations than Caucasian are required to better evaluate the contribution of MUC5B in the genetic IPF background in distinct populations. Distribution of T allele risk was not different according to gender. However woman represent only 18% of the cohort, that is less than the 28% of the Fairfax cohort [23].

Altogether, European data and meta-analysis confirm a strong association between the MUC5B rs35705950 variant and IPF in Caucasian population whereas this association was absent in SSc-related ILD. Further studies are required to evaluate this genetic susceptibility marker as a prognosis factor in IPF.

Supporting Information

Prisma flowchart.

(DOC)

Prisma guidelines.

(DOC)

Funding Statement

This work was supported by chancellerie des Universites de Paris, the DHU FIRE and PHRC Ile de France. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish,or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Steen VD, Medsger TA (2007) Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis 66: 940–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tansey D, Wells AU, Colby TV, Ip S, Nikolakoupolou A, et al. (2004) Variations in histological patterns of interstitial pneumonia between connective tissue disorders and their relationship to prognosis. Histopathology 44: 585–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Varga J, Abraham D (2007) Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest 117: 557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, et al. (2011) A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 364: 1503–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Y, Noth I, Garcia JG, Kaminski N (2011) A variant in the promoter of MUC5B and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 364: 1576–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, Peljto AL, Brown KK, et al.. (2013) Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Genet: [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma S, Flores C, Barber M, et al.. (2113) Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respiratory Medicine: Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Peljto AL, Steele MP, Fingerlin TE, Hinchcliff ME, Murphy E, et al. (2012) The Pulmonary Fibrosis-Associated MUC5B Promoter Polymorphism does not Influence the Development of Interstitial Pneumonia in Systemic Sclerosis. Chest 146: 1584–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stock CJ, Sato H, Fonseca C, Banya WA, Molyneaux PL, et al.. (2013) Mucin 5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with development of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis or sarcoidosis. Thorax [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161: 646–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dieude P, Guedj M, Wipff J, Ruiz B, Riemekasten G, et al. (2011) NLRP1 influences the systemic sclerosis phenotype: a new clue for the contribution of innate immunity in systemic sclerosis-related fibrosing alveolitis pathogenesis. Ann Rheum Dis 70: 668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, et al. (1988) Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 15: 202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Plantier L, Crestani B, Wert SE, Dehoux M, Zweytick B, et al. (2011) Ectopic respiratory epithelial cell differentiation in bronchiolised distal airspaces in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 66: 651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seibold MA, Smith RW, Urbanek C, Groshong SD, Cosgrove GP, et al. (2013) The idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis honeycomb cyst contains a mucocilary pseudostratified epithelium. PLoS One 8: e58658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahida R, Turner AM (2013) MUC5B: a good target for future therapy in pulmonary fibrosis? Thorax [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16. Valque H, Gouyer V, Gottrand F, Desseyn JL (2012) MUC5B leads to aggressive behavior of breast cancer MCF7 cells. PLoS One 7: e46699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peljto AL, Zhang Y, Fingerlin TE, Ma SF, Garcia JG, et al. (2013) Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JAMA 309: 2232–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bouros D, Wells AU, Nicholson AG, Colby TV, Polychronopoulos V, et al. (2002) Histopathologic subsets of fibrosing alveolitis in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relationship to outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goldin JG, Lynch DA, Strollo DC, Suh RD, Schraufnagel DE, et al. (2008) High-resolution CT scan findings in patients with symptomatic scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. Chest 134: 358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frech T, Khanna D, Markewitz B, Mineau G, Pimentel R, et al. (2010) Heritability of vasculopathy, autoimmune disease, and fibrosis in systemic sclerosis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 62: 2109–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dieude P, Guedj M, Wipff J, Avouac J, Fajardy I, et al. (2009) Association between the IRF5 rs2004640 functional polymorphism and systemic sclerosis: a new perspective for pulmonary fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dieude P, Guedj M, Wipff J, Ruiz B, Hachulla E, et al. (2009) STAT4 is a genetic risk factor for systemic sclerosis having additive effects with IRF5 on disease susceptibility and related pulmonary fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 2472–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nathan SD, Shlobin OA, Weir N, Ahmad S, Kaldjob JM, et al. (2011) Long-term course and prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the new millennium. Chest 140: 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swigris JJ, Olson AL, Huie TJ, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, et al. (2012) Ethnic and racial differences in the presence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at death. Respir Med 106: 588–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Prisma flowchart.

(DOC)

Prisma guidelines.

(DOC)