Abstract

The effect of locked nucleic acid (LNA) modification position upon representative DNA polymerase and exonuclease activities has been examined for potential use in primer extension genotyping applications. For the 3′→5′ exonuclease activities of four proofreading DNA polymerases (Vent, Pfu, Klenow fragment and T7 DNA polymerase) as well as exonuclease III, an LNA at the terminal (L-1) position of a primer is found to provide partial protection against the exonucleases of the two family B polymerases only. In contrast, an LNA residue at the penultimate (L-2) position generates essentially complete nuclease resistance. The polymerase active sites of these enzymes also display a distinct preference. An L-1 LNA modification has modest effects upon poly merization, but an L-2 LNA group slows dTTP incorporation somewhat while virtually abolishing extension with ddTTP or acyTTP terminators, even with A488L Vent DNA polymerase engineered for terminator incorporation. These observations on active site preference have been utilized to demonstrate two novel assays: exonuclease-mediated single base extension (E-SBE) and proofreading allele-specific extension (PRASE). We show that a model PRASE genotyping reaction with L-2 LNA primers offers greater specificity than existing non-proofreading assays, whether or not the non-proofreading reaction employs LNA-modified primers.

INTRODUCTION

Locked nucleic acids (LNA, also termed BNA by the Imanishi group) and closely related species such as ENA have been developed with the aim of improving nucleic acid recognition (1–3). Initially, the properties of increased thermal stability and selectivity of LNA:DNA and LNA:RNA duplexes over their natural counterparts encouraged investigation into antisense applications (4). In addition to binding target sequences with high affinity, LNAs were shown to be stable in serum, an important consideration for in vivo usage. Moreover, their lack of toxicity offered an important advantage over phosphorothioates. Further demonstrations of LNAs as antisense molecules (5,6), as well as an understanding of the impact of the modified nucleotide upon structure and RNase H activation (7–9) has confirmed their utility for these applications. Additionally, the unique properties of LNA modifications have been exploited to create DNAzymes (10) and fluorescent in situ hybridization probes (11) with greater target affinities, as well as transcription factor decoys that are nuclease resistant whilst maintaining their target selectivity (12).

Recently, the completion of several genome-sequencing projects has provided the impetus for an explosion in single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping technologies. These technologies are generally based upon the ability to discriminate or identify different nucleotide sequences and rely on at least one of four fundamental methodologies: hybridization, polymerization, ligation or nucleolysis. With LNAs possessing high hybridization affinity and target selectivity, it is unsurprising that they are beginning to be utilized in this arena. Assays based upon the ability of allele-specific LNA capture probes to discriminate between matched and mismatched targets with enhanced signal-to-noise have been described. These enzyme-independent genotyping methods have used colorimetry (13–15), direct fluorescence (16) or fluorescence polarization (17) to signal the hybridization event, and can be run in parallel or multiplexed formats. While hybridization-based assays have the advantage of simplicity, they fail to utilize the well recognized fidelity and robustness of nucleic acid modifying enzymes. In the sole enzyme-dependent LNA genotyping assay reported to date, allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) has been demonstrated using oligonucleotides containing a single LNA nucleotide at the 3′ terminus of the primer (18). In this implementation, the native ability of a polymerase to extend a primer terminus only if correctly matched with the template was improved by the superior discrimination capability of the terminal LNA residue. As this assay has demonstrated, enhanced genotyping methodologies may be developed by merging the compatible properties of LNAs and enzymes. The presence of LNA nucleotides also has a strong effect upon other enzyme functions, as demonstrated by nuclease resistance (1,4,9,12,19,20).

In order for LNAs to be more effectively utilized in genotyping assays, a better understanding of the interactions and effects of these modified nucleic acids upon enzyme function must be obtained. Here we examine the effect of LNA modifications upon exonucleolysis and polymerization of primer oligonucleotides, concentrating on the impact of modification position. Novel functions are developed in proof-of-concept genotyping assays that further demonstrate the value of LNAs in this field.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes were obtained from Promega, Fermentas or New England Biolabs. The A488L Vent DNA polymerase mutant (21) was kindly provided by William E. Jack of New England Biolabs. Basic chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as supplied. Nucleotides were from Promega or Fermentas. Cy3-dCTP was from Amersham Biosciences.

Oligonucleotides

All oligonucleotides were purchased from Proligo in desalted form. LNA modifications are underlined and bold in the sequences of Table 1.

Table 1. Oligonucleotide sequences.

| PAI-L0 |

H2N-GTCCTGGTGAATGCTGTCTACTT |

| PAI-L1 |

H2N-GTCCTGGTGAATGCTGTCTACTT |

| PAI-L2 |

H2N-GTCCTGGTGAATGCTGTCTACTT |

| PAI-L1,2 |

H2N-GTCCTGGTGAATGCTGTCTACTT |

| PAI-T1 |

AAGTAGACAGCATTCACCAGGAC |

| PAI-T2a |

TTGACAAAGTAGACAGCATTCACCAGGAC |

| PAI-T2g |

TTCATGAAGTAGACAGCATTCACCAGGAC |

| PAP-1g |

AGTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAG |

| PAP-1a |

AGTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAA |

| PAP-2a |

GTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAGA |

| PAP-2g |

GTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAGG |

| PAP-1gL1 |

AGTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAG |

| PAP-1aL1 |

AGTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAA |

| PAP-2aL1 |

GTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAGA |

| PAP-2gL1 |

GTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAGG |

| PAP-1gL2 |

AGTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAG |

| PAP-1aL2 |

AGTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAA |

| PAP-2aL2 |

GTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAGA |

| PAP-2gL2 |

GTTACCCCCATGACTCCAGAGG |

| PAP-revL2 | CTCGCAGACTTCTCACCAAAC |

Melting analysis

Complementary oligonucleotides (2 nmol each in 500 µl of phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4) were heated to 98°C and slow-cooled prior to analysis. Quartz cuvettes containing the samples were monitored at 260 nm in a Cary 100 Bio spectrophotometer (Varian). Temperatures were ramped from 20 to 98°C at the rate of 1°C/min. Measurements were performed in triplicate. Melting temperatures were calculated with the Cary 100 Thermal software using either differential or Van’t Hoff methods.

Exonucleolytic degradation

Oligonucleotides (100 pmol) were incubated in 20 µl of 1× supplied reaction buffer with 1–3 units of exo+ DNA polymerases [Vent, Pfu, T7 or Klenow fragment (KF)] or 0.1–250 units of exonuclease III (exo III) at optimal enzyme temperatures. Following incubation for 0–36 h (30 min for exo III), reactions were stopped by heating and/or addition of formamide–EDTA and samples run on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, which were stained with Sybr Green II (Sigma), visualized under UV light and densitometry performed with LabImage software (Kapelan). Background-corrected band intensities were fit to the equation I = A(1 + e–kt) to obtain the decay rate constant k. Half-lives were calculated from the rate.

Primer extension

Typically, a 10 µl reaction mixture contained 60 pmol of primer, 60 pmol of PAI-T2a template oligonucleotide, 100 µM nucleotide substrate (dTTP, ddTTP, acyTTP or aminoallyl-dUTP) and 1.0 or 0.2 units of DNA polymerase per 100 pmol of primer. Reactions were allowed to proceed for 0–16 h before stopping by heat treatment (for labile polymerases) or snap freezing in –80°C ethanol (for thermostable polymerases). Subsequent product digestion was performed by overnight incubation with 50 units of exo III at 15°C. All reactions were performed in triplicate. Samples were run on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, stained with Sybr Green II and analysed. Background-corrected intensities were fit to the equation I = A(1 – e–kt) to obtain the extension rate constant k.

Arrayed primer extension (APEX)

Amino-linked oligonucleotide primers were spotted onto epoxide-modified glass slides (Eppendorf) at concentrations ranging from 80 nM to 50 µM in 150 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 8 using a robotic spotter (ESI) and Telechem Stealth pins. Each primer concentration was spotted 20 times, with the entire array set spotted in duplicate on every slide. Following overnight air-drying at room temperature, slides were baked at 65°C for 30 min, then washed for 1 min each in hot 0.1% SDS, 5% ethanol and ddH2O. Reaction mixtures (140 µl) containing 5 µM of either PAI-T2a or PAI-T2g templates, 25 µM Cy3-dCTP (and 25 µM dATP, dTTP, dGTP when required) and 1 unit of Therminator DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) in 1× supplied reaction buffer were incubated below a cover slip on the arrayed slides in a humidity-chamber at 60°C for 2 h. Following three washes with 0.1% SDS and two washes with ddH2O, one array on each slide was covered with reaction buffer only, while the other array was covered with buffer containing 200 units of exo III and incubated overnight at 37°C. After additional washes, slide scans were carried out with an ArrayworX scanner (Applied Precision) monitoring emission at 595 nm. Post-scan analysis was performed using Axon Genepix Pro software.

Allele-specific PCR

In general, reactions (10 µl) were performed using 10 pmol of each primer, with 250 µM dNTPs, 10 amol of template (20 pg of a 3.4 kb plasmid containing a 400 bp PAI-2 gene fragment) and 0.5 units of Vent DNA polymerase in 1× Vent reaction buffer. PCR conditions for the exo– reactions were 25 cycles of 20 s at 96°C, 20 s at 48°C and 90 s at 68°C. For the exo+ reactions, 35 cycles were used.

RESULTS

Melting analysis

To examine the effects of LNA modifications upon oligonucleotide duplex stability, melting analysis was performed on perfect 23mer duplexes derived from the human plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 (PAI-2, SERPINB2) gene. All duplexes contained the native PAI-T1 template strand (Table 1). The other strand of each perfect complement contained LNA nucleotides at either the 3′ terminus (L-1 position: primer PAI-L1), the penultimate position relative to the 3′ terminus (L-2 position: primer PAI-L2), both positions (L-1,-2: primer PAI-L1,2) or neither position (primer PAI-L0). Observed melting temperatures indicate a small destabilization of the duplex with the inclusion of a terminal LNA residue (Tm = 67.0 ± 1.0°C for PAI-L1 versus 70.3 ± 0.7°C for unmodified oligonucleotide), whereas no net change is observed when the LNA nucleotide is at the penultimate position (Tm = 70.4 ± 0.6°C for PAI-L2). When both penultimate and terminal positions are LNA modified, the duplex is again destabilized, but to a lesser degree than that for a terminal LNA alone (Tm = 68.1 ± 0.3°C for PAI-L1,2). This is consistent with reports that multiple internal LNA residues cause large increases in duplex thermal stability (1,19), while oligonucleotides with single terminal LNA residues display somewhat reduced stability (18,22).

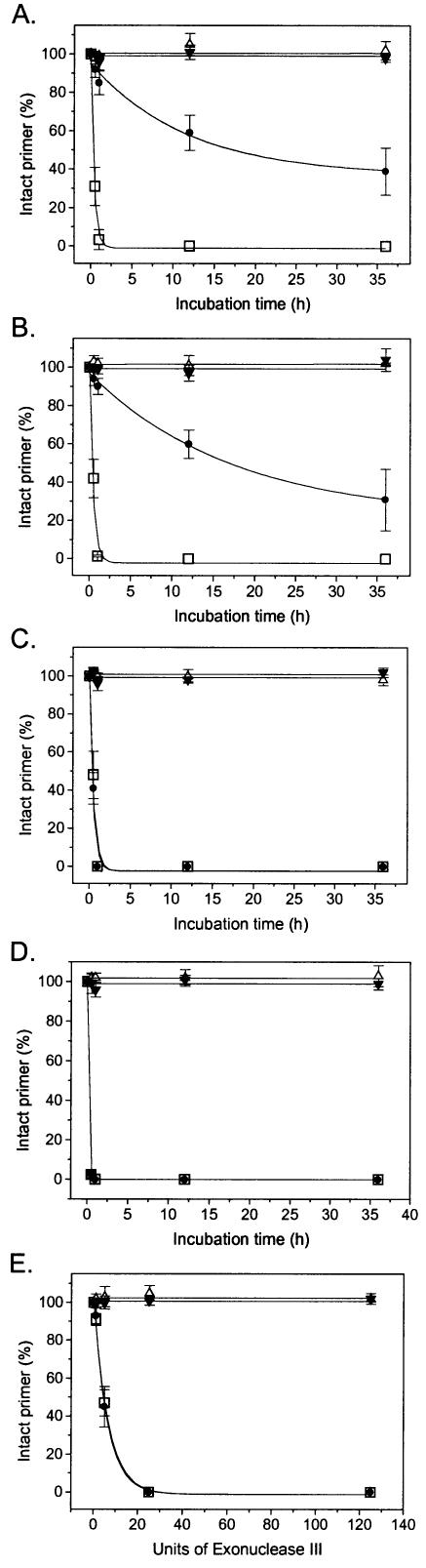

Exonuclease resistance

In addition to being essential for applications in biological fluids, stabilization of oligonucleotides against exonucleases is also important for genosensing and genotyping methodologies that utilize polymerases with proofreading 3′→5′ exonuclease activities (exo+). Such enzymes can be used for high fidelity nucleotide addition in SNP genotyping assays (23,24), but degrade any oligonucleotides that are not protected at their 3′ termini. To test the ability of LNA nucleotides to retard exonucleolysis, primers were incubated with various exo+ polymerases as well as exo III and the amount of intact oligonucleotide measured over time (Fig. 1A–E). While the native DNA oligonucleotide PAI-L0 is rapidly degraded in an exponential manner by the exonuclease activities of all polymerases (t1/2 = 0.10–0.36 h), the LNA-modified oligonucleotides display different patterns. The L-1 LNA-modified PAI-L1 is partially protected against both Pfu and Vent DNA polymerases, with degradation rates (t1/2 = 17.3 and 16.9 h, respectively, for 3 units of enzyme) significantly slower than that of PAI-L0. However, when incubated with KF or T7 DNA polymerase (t1/2 = 0.32 and 0.1 h, respectively), the L-1 LNA modification is degraded as rapidly as the native oligonucleotide. In contrast, no degradation could be detected for the PAI-L2 (L-2-modified) and PAI-L1,2 (L-1,-2-modified) species with any of the polymerases tested, even following extended incubations at high enzyme concentrations (Fig. 1A–D). Exo III degraded these oligonucleotides in a pattern mirroring that of KF and T7 DNA polymerases (Fig. 1E). This set of results indicates that a single LNA at the penultimate (L-2) nucleotide position relative to the 3′ terminus is sufficient to provide complete protection against 3′→5′ exonuclease activity.

Figure 1.

Exonucleolysis of natural and LNA-modified oligonucleotides with (A) Pfu DNA polymerase, (B) exo+ A488L Vent DNA polymerase, (C) exo+ Klenow DNA polymerase, (D) T7 DNA polymerase and (E) exo III. Oligonucleotides are PAI-L0 (squares), PAI-L1 (circles), PAI-L2 (triangles) and PAI-L1,2 (inverted triangles).

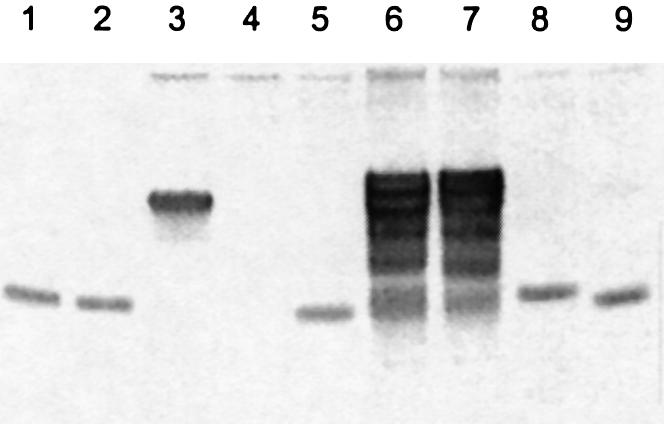

To further explore this observation, both the L-1-modified (PAI-L1) and L-2-modified (PAI-L2) primers (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 2) were extended by exo– Vent DNA polymerase in the presence of all four natural nucleoside triphosphates and the complementary PAI-T2a template (Fig. 2, lane 3) that contains a six base overhang. As expected, PAI-L2 is the only nuclease-resistant species prior to extension (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 5). Following primer extension (Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 7), excess exo III was used to degrade all sensitive nucleotides (Fig. 2, lanes 8 and 9). The extended PAI-L2 primer is degraded back to its original length by this treatment (Fig. 2, lane 9), as expected. On the other hand, PAI-L1 is converted to a form that could no longer be degraded, one nucleotide longer than the original (Fig. 2, lane 8). This unequivocally demonstrates that oligonucleotides are protected against 3′→5′ exonucleolysis when an LNA residue is present at the L-2 position. The extension of an L-1 LNA primer followed by 3′→5′ exonuclease degradation thus provides a novel mechanism for protecting an incoming nucleotide from subsequent removal.

Figure 2.

Exonucleolysis of LNA-modified primers before and after primer extension. Lanes: 1, PAI-L1 standard; 2, PAI-L2 standard; 3, PAI-T2a template standard; 4, exonuclease-III-treated PAI-L1 + PAI-T2a duplex; 5, exonuclease-III-treated PAI-L2 + PAI-T2a duplex; 6, PAI-L1 + PAI-T2a duplex extended with dTTP; 7, PAI-L2 + PAI-T2a duplex extended with dTTP; 8, exonuclease-III-treated PAI-L1 + PAI-T2a duplex following extension with dTTP; and 9, exonuclease-III-treated PAI-L2 + PAI-T2a duplex following extension with dTTP.

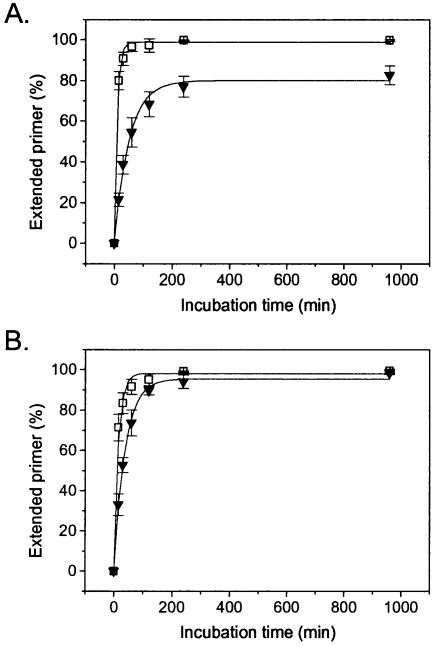

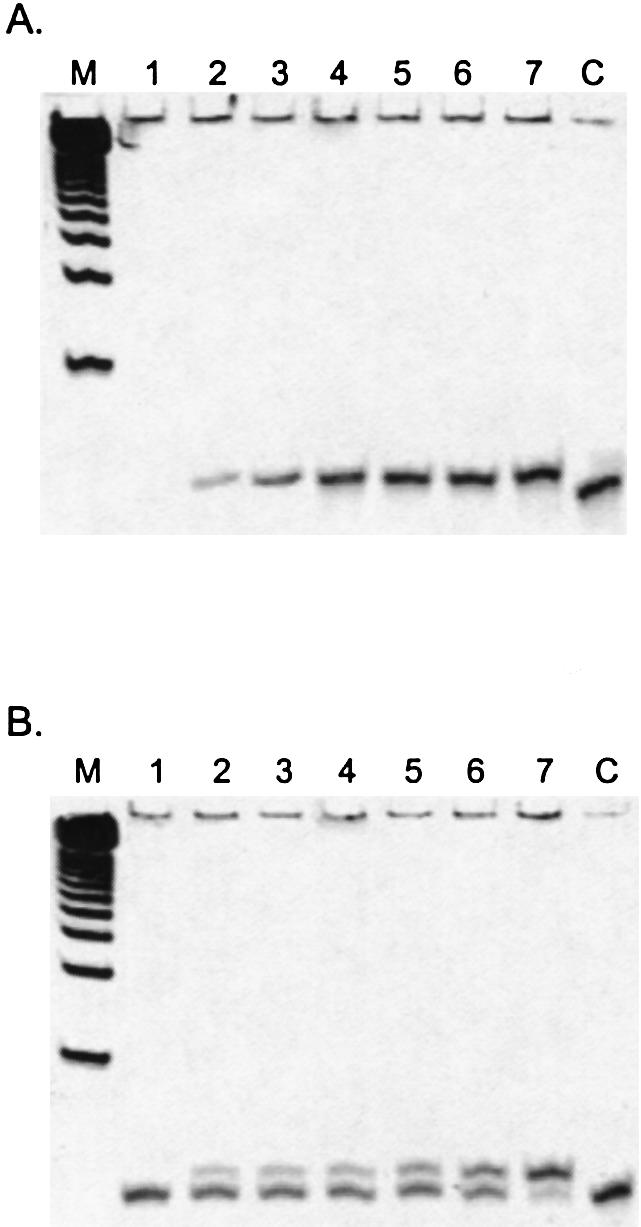

Primer extension

With many genotyping methods based upon primer extension (25), the effect of LNA residues on polymerase reaction rate becomes an important consideration. By using L-1 LNA-modified PAI-L1 and the L-1,-2 LNA-modified PAI-L1,2 primers, extension reactions can be followed by exo III digestion to reveal the degree of extension solely at the level of the first incoming nucleotide, even for non-terminating substrates. For PAI-L1, only extended primer remains following degradation (Fig. 3A), while PAI-L1,2 is partitioned between unextended and mono-extended forms (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Polyacrylamide gel time course of LNA-modified primer extension by 0.2 units of exo– A488L Vent DNA polymerase with aminoallyl-dUTP, followed by exo III digestion. (A) PAI-L1. (B) PAI-L1,2. Lanes: M, 25 bp ladder; 1, 0 min; 2, 15 min; 3, 30 min; 4, 60 min; 5, 120 min; 6, 240 min; 7, 960 min; and C, undigested oligonucleotide control.

Whereas extension of PAI-L1 with dTTP proceeds rapidly for either exo– KF or exo– A488L Vent DNA polymerase, PAI-L1,2 is extended 3- to 6-fold more slowly, an effect more pronounced for KF than for A488L Vent DNA polymerase (Fig. 4A and B and Table 2). Under the conditions employed here, the rate of KF extension drops from 10.0 to 1.6 pmol/min, while A488L Vent DNA polymerase slows from 8.0 to 2.5 pmol/min (Table 2). When nucleobase-modified aminoallyl-dUTP is used as substrate, KF can only extend PAI-L1 at a modest rate (0.9 pmol/min), with no measurable extension of PAI-L1,2. In contrast, A488L Vent DNA polymerase is unaffected by the use of this substrate, with extension rates comparable to those observed with dTTP for both primers (Table 2). When the terminators ddTTP or acyTTP are used as substrates, KF does not extend either primer, consistent with the known incompatibility of this enzyme with terminators (26). The A488L Vent DNA polymerase mutant, engineered for use with terminators (21), successfully extends PAI-L1 at rates similar to that observed with the natural dTTP substrate (Table 2). Interestingly, no extension of PAI-L1,2 is observed for either A488L Vent-terminator combination, even following long incubation periods at high enzyme concentrations (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Polymerase-mediated extension of LNA-modified primers with dTTP by (A) exo– Klenow DNA polymerase and (B) exo– A488L Vent DNA polymerase. Oligonucleotides are PAI-L1 (squares) and PAI-L1,2 (inverted triangles).

Table 2. Rate of extension (pmol/min) of LNA-modified primers with deoxy-, dideoxy- and acyclo-substrates by 1 unit of exo– KF or exo– A488L Vent DNA polymerase.

| Enzyme | Primer | dTTP | ddTTP | acyTTP | aaUTP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF |

PAI-L1 |

10.0 (3.8) |

0 |

0 |

0.9 (0.4) |

| |

PAI-L1,2 |

1.6 (0.5) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Vent |

PAI-L1 |

8.0 (2.0) |

5.2 (1.7) |

9.4 (2.5) |

8.4 (1.0) |

| PAI-L1,2 | 2.5 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 3.5 (0.2) |

Standard deviations appear in parentheses. Zero rates reflect experimentally undetectable extension over a period of 16 h.

Exonuclease-mediated single base extension (E-SBE) on arrayed primers

Our observations on LNA positional effects were used to generate a single-base APEX microarray genotyping assay that does not require terminator nucleotides. Arrays of L-1 LNA-modified primers were incubated with a solution of Cy3-dCTP, three unlabeled nucleotides, Therminator DNA polymerase and the PAI-T2g or PAI-T2a templates directing either dCTP or dTTP into the first extension position, respectively. One half of a slide was exposed to this treatment only (Fig. 5, panels 1 and 3), while the other half was exposed to an additional incubation with exo III (Fig. 5, panels 2 and 4). For both PAI-L0 and PAI-L1, all extension reactions produce brightly fluorescent spots, indicative of Cy3-dCTP incorporation. Following exo III treatment, the natural PAI-L0 primers are largely degraded, removing previously incorporated Cy3-dCTP nucleotides (Fig. 5A, panels 2 and 4). With the PAI-L1 primer protecting the first extended nucleotide from exonucleolysis, spots incubated with PAI-T2g template retain most of their fluorescence (Fig. 5B, panel 2). On the other hand, the PAI-L1 spots incubated with the PAI-T2a template now display no fluorescence, with every incorporated Cy3-dCTP residue removed, leaving only an unlabeled dTTP as the first incorporated nucleotide (Fig. 5B, panel 4). When the background-corrected median pixel intensity is averaged across 20 replicate spots, the ratio of Cy3 fluorescence from correct and incorrect template incubations gives an indication of the signal-to-noise characteristic for this assay. For PAI-L0, these ratios averaged 2.7 ± 1.3 across all spotted oligonucleotide concentrations. In comparison, the smallest ratio for PAI-L1 was 13.7, with other spotted primer concentrations giving ratios ranging up to infinity. This performance indicates that the E-SBE assay is perfectly suitable for bi-allelic genotyping and can be employed for more quantitative applications following optimization.

Figure 5.

Exonuclease-mediated APEX of five replicated spots with (A) PAI-L0 and (B) PAI-L1. Using PAI-T2g as a template, primers were (1) extended with Cy3-dCTP, dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and then (2) treated with exo III to degrade susceptible nucleotides. Using PAI-T2a as a template, primers were (3) extended with Cy3-dCTP, dATP, dTTP, dGTP and then (4) treated with exo III.

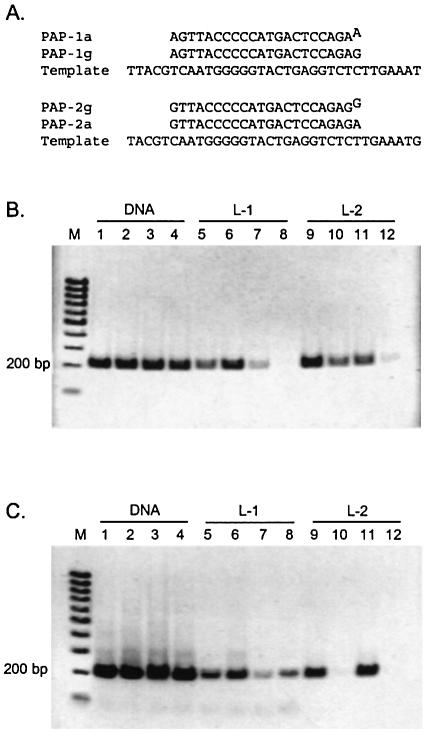

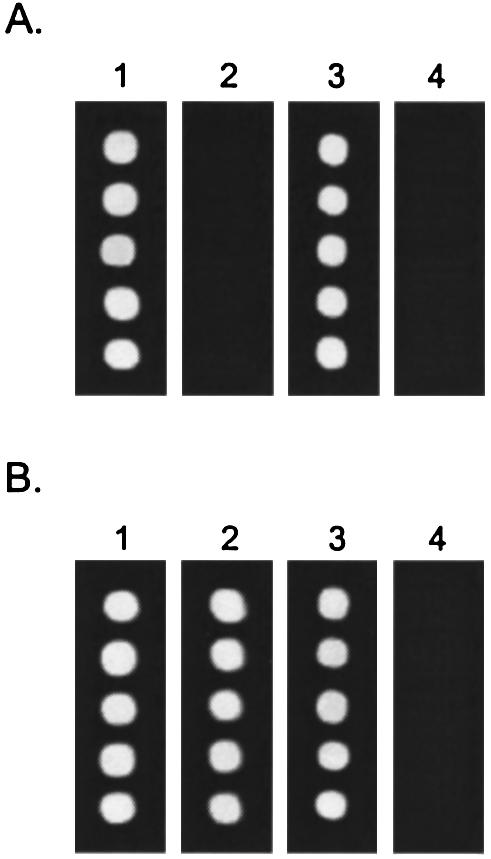

Proofreading allele-specific extension (PRASE) PCR

With conventional allele-specific extension (ASE) limited by the inability of exo– DNA polymerases to discriminate some terminal mismatches using natural oligonucleotides (27,28), we have examined whether the proofreading exo+ Vent DNA polymerase has an increased ability to generate accurate AS-PCR products from LNA-protected primers. Using G:C→A:C and A:T→G:T transitions as model mutations known to be difficult to distinguish by ASE-PCR (18,29), matched and mismatched natural, L-1 or L-2 LNA primers were used in amplification reactions with both exo– and exo+ variants of Vent DNA polymerase. The PAP-1 group of primers was designed to hybridize to the PAI-2 gene such that their 3′ terminal residues lie opposite a C template nucleotide. Likewise, the PAP-2 group of primers hybridize with their 3′ nucleotide opposite to a T template residue (Fig. 6A). Thus, the PAP-1g and PAP-2a primers are fully complementary, while PAP-1a and PAP-2g primers are mismatched at their 3′ position. Amplification of a cloned PAI-2 gene fragment in the presence of the PAP-revL2 reverse primer generates a 207 bp PCR amplicon in this system. In the PAGE images of Figure 6B and C, amplification reactions are shown in groups of four: the second and fourth lanes of each group contain correct amplification products, while the first and third lanes contain incorrect mismatch extension products.

Figure 6.

Demonstration of PRASE PCR. (A) Forward allele-specific primers and template sequences. (B) PCR amplicons generated with exo– Vent DNA polymerase. (C) PCR amplicons generated with exo+ Vent DNA polymerase. Lanes: M, 100 bp marker ladder and PCR amplicons generated with forward primers. Standard primers: 1, PAP-1g; 2, PAP-1a; 3, PAP-2a and 4, PAP-2g; L-1 LNA-modified primers: 5, PAP-1gL1; 6, PAP-1aL1; 7, PAP-2aL1; 8, PAP-2gL1; and L-2 LNA-modified primers: 9, PAP-1gL2; 10, PAP-1aL2; 11, PAP-2aL2; and 12, PAP-2gL2.

Non-proofreading ASE amplifications with exo– Vent DNA polymerase were performed first (Fig. 6B). For these reactions, neither natural DNA nor L-1 LNA series primers exhibit an ability to properly discriminate between correctly matched and mismatched termini (Fig. 6B, lanes 1–4 and 5–8, respectively). In fact, the incorrect amplicon even predominates under some circumstances (Fig. 6B, lane 6). For this non-proofreading assay the L-2 primer series demonstrates improved discrimination over the other primer constructs (Fig. 6B, lanes 9–12), but still produces significant levels of mismatch PCR products (Fig. 6B, lanes 10 and 12).

The introduction of proofreading exo+ Vent DNA polymerase into the ASE assay substantially improves discrimination performance (Fig. 6C). The natural DNA and L-1 series primers continue to poorly discriminate matched from mismatched primer termini (Fig. 6C, lanes 1–4 and 5–8, respectively). However, combination of the L-2 series primers with the proofreading DNA polymerase results in a robust assay outcome, with strong product generation for correctly matched primer termini (Fig. 6C, lanes 9 and 11) and negligible product for incorrectly matched termini (Fig. 6C, lanes 10 and 12). Use of a doubly modified L-1,-2 allele-specific primer yields results comparable to those for the L-2 primer.

DISCUSSION

With an emphasis on improving stability and specificity, nucleic acid analogs are finding numerous applications in contemporary molecular biology. LNA is one such analog that has recently gained much attention for its favorable properties. The stability of LNA-modified oligonucleotides in biological fluids, lack of toxicity and improved hybridization behavior have made this a promising tool for use in antisense applications (1,4). Moreover, the heightened ability to discriminate between matched and mismatched target nucleic acids has promptly attracted the attention of the genotyping community. Since hybridization-based genotyping methodologies are limited by the presence of thermally stable mismatches, the inclusion of LNA residues in probe oligonucleotides has significantly improved their differentiation characteristics (13,14,16–18). With an improved understanding of their interactions with enzymes, it may be possible to develop additional genotyping technologies that integrate and utilize the favorable properties of this modification.

For the majority of enzyme-based genotyping methods, manipulation of oligonucleotide termini forms the basis of the detection mechanism. We have focused upon the impact of LNA nucleotides at the primer 3′ terminus on the basic processes of exonucleolysis and polymerization employed by proofreading DNA polymerases. It is clear from this work that the number and positioning of these modified nucleotides has distinct and specific effects upon enzyme function, which can be utilized for novel assays. These effects appear to be relatively general, but significant differences can be observed between different polymerase families.

Exonucleolysis

In the case of degradation by 3′→5′ exonucleolysis, the presence of a single 3′ terminal (L-1) LNA residue significantly slows degradation by the 3′→5′ proofreading exonuclease activities of the family B DNA polymerases Pfu and Vent (Fig. 1A and B), whereas the exonuclease function of the family A polymerases T7 DNA polymerase and KF is not significantly impeded (Fig. 1C and D). When a single LNA group is moved to the penultimate (L-2) position, however, complete resistance to degradation is observed for all enzymes tested, including exo III (Fig. 1A–E). With Crinelli and co-workers demonstrating that more than one terminal LNA nucleotide is needed to provide protection against the Bal31 exonuclease (12), the penultimate nucleotide at either end of an oligonucleotide is likely to be the critical position for protection against exonucleases of all relevant classes. This conclusion should be applicable to both antisense and genotyping applications.

Polymerization

LNA positioning at and near the 3′ terminus of a primer can significantly affect polymerase-mediated extension. Whereas an L-1 LNA nucleotide does not substantially slow primer extension with a natural deoxy-NTP substrate under the conditions we have examined, an additional LNA at the L-2 position causes the polymerization rate to drop by almost an order of magnitude in the case of KF (Figs 3 and 4 and Table 2). The cause of this rate reduction may be inferred from preliminary modeling of an LNA oligonucleotide into the active site of Taq DNA polymerase, a member of the same polymerase family. Whereas native DNA is found in the 2′-endo conformation, the methylene bridge between the 2′-oxygen and 4′-carbon of the sugar in LNA nucleotides results in a 3′-endo conformation (8). For an L-1 LNA oligonucleotide, this change results in very little perturbation of the backbone, with the reactive hydroxyl of the terminal sugar positioned in approximately the same location within the active site. However, locking at the L-2 position causes a significant conformational change of the phosphodiester backbone and repositioning of the terminal nucleotide. The terminal phosphodiester repositioned by the L-2 LNA group is also in close contact with polymerase amino acid side chains, which may further contribute to active site deformation. As the inclusion of several internal LNA nucleotides leads to conformational changes that induce a transition from B-form to A-form duplex DNA (30), this may present an upper limit to the number of modified nucleotides that can be included within a primer to be used in enzymatic reactions sensitive to such structural changes. For KF, the lack of appreciable L-1 LNA primer extension with terminators is consistent with the substrate preference of this enzyme (24), while the A488L Vent DNA polymerase mutant displays behavior consistent with its own terminator preference (21).

The reasons for the complete lack of detectable extension of the double L-1,-2 PAI-L1,2 primer with terminator nucleotides (Table 2), even for the A488L Vent DNA polymerase mutant engineered for terminator incorporation, are less clear. As this refractory behavior is also observed for singly modified L-2 primers (E. Flening and G.C. King, unpublished results), it is a direct consequence of the L-2 modification. Probably, suboptimal binding of terminators in the polymerase active site cannot adequately compensate for the conformational changes due to the L-2 LNA residue. Extensive modeling studies on a variety of polymerases should provide an insight into this issue and may be able to guide future mutagenesis programs. In the meantime, it is clear that the exonuclease protection afforded by the L-2 LNA modification is likely to be utilized only in reactions employing deoxy-NTP substrates, including nucleobase-modified conjugates as we have shown here (Fig. 3 and Table 2).

E-SBE

With the recent growth in the development of LNA-based genotyping assays, the utility of these modified primers in applications beyond antisense is now becoming clear. Here we have first utilized the differential stability of L-1 versus L-2 LNAs against 3′→5′ exonucleases in a novel E-SBE assay implemented in an APEX format. This assay does not require terminator nucleotides (Fig. 5). Because the E-SBE assay generates a final product with the LNA group at the exonuclease-resistant L-2 position, it cannot be used in a proofreading mode, but nonetheless has utility due to its relatively high signal-to-noise. The assay can be conducted with four differently labeled dNTPs as exo III is capable of degrading nucleobase-modified species (M. Aung and G.C. King, unpublished results).

PRASE

The potential fallibility of conventional AS-PCR assays, especially in the erroneous extension of some mismatches (27–29), has lead to the development of LNA-based AS-PCR methods (18,31). Our demonstration here of a robust L-2 LNA-based PRASE PCR assay refines and extends this application for use in SNP detection and allele quantitation. In the stringent test reaction employed here, PRASE outperforms the non-proofreading L-1 LNA-based assay, generating no detectable incorrect amplicon (Fig. 6B and C). The reasons for this improved discrimination are two-fold. The position of the LNA residue has a strong influence upon match/mismatch discrimination (Fig. 6B). The proofreading activity of DNA polymerases has also been described to improve discrimination (32). Further development and validation of real-time PRASE assays is underway.

The exploitation of an exo+ DNA polymerase to improve the fidelity of the PRASE assay also contributes further momentum towards the use of proofreading polymerases in genotyping methodologies, where the recent application of this concept has been used in primer extension methods (23,24) and in a novel exonucleolytic assay for SNP detection (33). Increased understanding of the effect of LNA moieties within oligonucleotide primers upon various enzymatic functions should result in further development of enzyme-dependent assays utilizing the novel characteristics of these and other modified nucleic acids.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Bill Jack (New England Biolabs) for the generous provision of A488L Vent DNA polymerases, Yu-Ching Lai for assistance with the processing of APEX microarray data and Eleanor Flening for discussions on LNA applications.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh S.K., Nielsen,P., Koshkin,A.A. and Wengel,J. (1998) LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis and high-affinity nucleic acid recognition. Chem. Commun., 4, 455–456. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obika S., Uneda,T., Sugimoto,T., Nanbu,D., Minami,T., Doi,T. and Imanishi,T. (2001) 2′-O,4′-C-methylene bridged nucleic acid (2′,4′-BNA): synthesis and triplex-forming properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem., 9, 1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morita K., Hasegawa,C., Kaneko,M., Tsutsumi,S., Sone,J., Ishikawa,T. and Imanishi,T. (2002) 2′-O,4′-C-ethylene-bridged nucleic acid (ENA): highly nuclease-resistant and thermodynamically stable oligonucleotides for antisense drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 12, 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahlestedt C., Salmi,P., Good,L., Kela,J., Johnsson,T., Hokfelt,T., Broberger,C., Porreca,F., Lai,J., Ren,K. et al. (2000) Potent and nontoxic antisense oligonucleotides containing locked nucleic acids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5633–5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braasch D.A., Liu,Y. and Corey,D.R. (2002) Antisense inhibition of gene expression in cells by oligonucleotides incorporating locked nucleic acids: effect of mRNA target sequence and chimera design. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 5160–5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elayadi A.N., Braasch,D.A. and Corey,D.R. (2002) Implications of high-affinity hybridization by locked nucleic acid oligomers for inhibition of human telomerase. Biochemistry, 41, 9973–9981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bondensgaard K., Petersen,M., Singh,S.K., Rajwanshi,V.K., Kumar,R., Wengel,J. and Jacobsen,J.P. (2000) Structural studies of LNA:RNA duplexes by NMR: conformations and implications for RNase H activity. Chem. Eur. J., 6, 2687–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen G.A., Singh,S.K., Kumar,R., Wengel,J. and Jacobsen,J.P. (2001) A comparison of the solution structure of an LNA:DNA duplex and the unmodified DNA:DNA duplex. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 7, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurreck J., Wyszko,E., Gillen,C. and Erdmann,V. (2002) Design of antisense oligonucleotides stabilized by locked nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 1911–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vester B., Lundberg,L.B., Sorensen,M.D., Babu,B.R., Douthwaite,S. and Wengel,J. (2002) LNAzymes: incorporation of LNA-type monomers into DNAzymes markedly increases RNA cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 13682–13683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silahtaroglu A.N., Tommerup,N. and Vissing,H. (2003) FISHing with locked nucleic acids (LNA): evaluation of different LNA/DNA mixmers. Mol. Cell. Probes, 17, 165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crinelli R., Bianchi,M., Gentilini,L. and Magnani,M. (2002) Design and characterization of decoy oligonucleotides containing locked nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 2435–2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orum H., Jakobsen,M.H., Koch,T., Vuust,J. and Borre,M.B. (1999) Detection of the factor V Leiden mutation by direct allele-specific hybridization of PCR amplicons to photoimmobilized locked nucleic acids. Clin. Chem., 45, 1898–1905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen N., Fenger,M., Bentzen,J., Rasmussen,S.L., Jakobsen,M.H., Fenstholt,J. and Skouv,J. (2002) Genotyping of the apolipoprotein B R3500Q mutation using immobilized locked nucleic acid capture probes. Clin. Chem., 48, 657–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen N., Bentzen,J., Meldgaard,M., Jakobsen,M.H., Fenger,M., Kauppinen,S. and Skouv,J. (2002) LNA-enhanced detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the apolipoprotein E. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choleva Y., Norholm,M., Pedersen,S., Mouritzen,P., Hoiby,P.E., Nielsen,A.T., Moller,S., Jakobsen,M.H. and Kongsbak,L. (2001) Multiplex SNP genotyping using locked nucleic acid and microfluidics. J. Assoc. Lab. Automat., 6, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simeonov A. and Nikiforov,T.T. (2002) Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using short, fluorescently labeled locked nucleic acid (LNA) probes and fluorescence polarization detection. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latorra D., Campbell,K., Wolter,A. and Hurley,J.M. (2003) Enhanced allele-specific PCR discrimination in SNP genotyping using 3′ locked nucleic acid (LNA) primers. Hum. Mutat., 22, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar R., Singh,S.K., Koshkin,A.A., Rajwanshi,V.K., Meldgaard,M. and Wengel,J. (1998) The first analogues of LNA (locked nucleic acids): phosphorothioate-LNA and 2′-thio-LNA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 8, 2219–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauritsen A., Dahl,B.M., Dahl,O., Vester,B. and Wengel,J. (2003) Methylphosphonate LNA: a locked nucleic acid with a methylphosphonate linkage. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 13, 253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner A.F. and Jack,W.E. (2002) Acyclic and dideoxy terminator preferences denote divergent sugar recognition by archaeon and Taq DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 605–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen U., Christensen,N., Rajwanshi,V., Wengel,J. and Koch,T. (2001) Stopped-flow kinetics of locked nucleic acid (LNA)-oligonucleotide duplex formation: studies of LNA-DNA and DNA-DNA interactions. Biochem. J., 354, 481–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Giusto D.A. and King,G.C. (2003) Single base extension (SBE) with proofreading polymerases and phosphorothioate primers: improved fidelity in single-substrate assays. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J., Li,K., Liao,D., Pardinas,J.R., Chen,L. and Zhang,X. (2003) Different applications of polymerases with and without proofreading activity in single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Lab. Invest., 83, 1147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syvanen A.-C. (2001) Accessing genetic variation: genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature Rev. Genet., 2, 930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner A.F. and Jack,W.E. (1999) Determinants of nucleotide sugar recognition in an archaeon DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2545–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwok S., Kellogg,D.E., McKinney,N., Spasic,D., Goda,L., Levenson,C. and Sninsky,J.J. (1990) Effects of primer-template mismatches on the polymerase chain reaction: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 model studies. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Z., Liu,Q. and Smith,L.M. (1997) Enhanced discrimination of single nucleotide polymorphisms by artificial mismatch hybridization. Nat. Biotechnol., 15, 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang M.M., Arnheim,N. and Goodman,M.F. (1992) Extension of base mispairs by Taq DNA polymerase: implications for single nucleotide discrimination in PCR. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 4567–4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen M., Bondensgaard,K., Wengel,J. and Jacobsen,J.P. (2002) Locked nucleic acid (LNA) recognition of RNA: NMR solution structures of LNA:RNA hybrids. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 5974–5982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ugozzoli L.A., Latorra,D., Pucket,R., Arar,K. and Hamby,K. (2004) Real-time genotyping with oligonucleotide probes containing locked nucleic acids. Anal. Biochem., 324, 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Y.-W., Balaskas,E., Kessler,G., Issid,C., Scully,L.J., Murphy,D.G., Rinfret,A., Giulivi,A., Scalia,V. and Gill,P. (1998) Primer specific and mispair extension analysis (PSMEA) as a simple approach to fast genotyping. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 5013–5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cahill P., Bakis,M., Hurley,J., Kamath,V., Nielsen,W., Weymouth,D., Dupuis,J., Doucette-Stamm,L. and Smith,D.R. (2003) Exo-proofreading, a versatile SNP scoring technology. Genome Res., 13, 925–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]