Abstract

Background

Reverse obliquity fractures of the proximal femur have biomechanical characteristics distinct from other intertrochanteric fractures and high implant failure rate when treated with sliding hip screws. Intramedullary hip nailing for these fractures reportedly has less potential for cut-out of the lag screw because of their loadbearing capacity when compared with extramedullary implants. However, it is unclear whether nail length influences healing.

Questions/purposes

We compared standard and long types of intramedullary hip nails in terms of (1) reoperation (fixation failure), (2) 1-year mortality rate, (3) function and mobility, and (4) union rate.

Methods

We conducted a pilot prospective randomized controlled trial comparing standard versus long (≥ 34 cm) intramedullary hip nails for reverse obliquity fractures of the proximal femur from January 2009 to December 2009. There were 15 patients with standard nails and 18 with long nails. Mean age was 79 years (range, 67–95 years). We determined 1-year mortality rates, reoperation rates, Parker-Palmer mobility and Harris hip scores, and radiographic findings (fracture union, blade cut-out, tip-apex distance, implant failure). Minimum followup was 12 months (mean, 14 months; range, 12–20 months).

Results

We found no difference in reoperation rates between groups. Two patients (both from the long-nail group) underwent revision surgery because of implant failure in one and deep infection in the other. There was no difference between the standard- and long-nail groups in mortality rate (17% versus 18%), Parker-Palmer mobility score (five versus six), Harris hip score (74 versus 79), union rate (100% in both groups), blade cut-out (zero versus one), and tip-apex distance (22 versus 24 mm).

Conclusions

Our preliminary data suggest reverse obliquity fractures of the trochanteric region of the femur can be treated with either standard or long intramedullary nails.

Level of Evidence

Level II, therapeutic study. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Intertrochanteric hip fracture incidence is expected to increase as the population ages. It is one of the most important causes of mortality and morbidity in the geriatric population [27]. The major fracture in most fractures runs obliquely from the greater trochanter proximally to the lesser trochanter distally. The reverse obliquity fracture has the opposite configuration and is characterized by having a fracture exiting the lateral femoral cortex distal to the vastus ridge. The incidence of reverse obliquity fractures of the proximal femur is reportedly relatively low. Haidukewych et al. [10] calculated the incidence as 5.3% during a 10-year period and Min et al. [17] found an incidence of 4.3%. Park et al. [19], on the other hand, reported an incidence of 15% and Honkonen et al. [12] 23% in busy, centralized trauma centers.

Sliding hip screws (SHSs) are reportedly reliable implants for treating many intertrochanteric fractures of the proximal part of the femur. In a prospective randomized study of 210 patients with intertrochanteric fractures treated with either a SHS or a long Gamma® nail, Barton et al. [3] found no differences between groups in reoperation rates, mortality rates, or EuroQol 5D scores. Although many surgeons prefer a SHS for fixing stable fractures [4, 24, 26], the intramedullary nail (IMN) reportedly has greater mechanical resistance to failure, a loadbearing device, and thus increased mechanical stability in unstable fractures, especially the reverse oblique types [15, 20, 22]. The proximal thick part of the nail leans against the proximal fragment preventing medialization of the shaft. As there is no medial buttress in this type of fracture, some studies [1, 13, 17, 19] suggest reverse oblique fractures of the proximal femur should be treated with an IMN to reduce the risk of implant failure and subsequent nonunion or cut-out of the lag screw.

Almost every hip IMN has standard and long versions (varying from 30 to 42 cm) for fixing the proximal part of femoral fractures. Although the number of lengths available for long versions would not be suitable for all femurs from the greater trochanter to the condylar notch, the routine use of long IMNs for the fixation of proximal femoral fractures seems logical for splinting the maximum length of the bone. However, the indications for choosing either a standard or long IMN are somewhat unclear and usually subjective [2], and it is unclear whether long nails reduce the rates of reoperation and nonunion.

We therefore compared (1) reoperation rate during the first postoperative year, (2) 1-year mortality rate, (3) Parker-Palmer mobility score and Harris hip score (HHS) at latest followup, and (4) fracture union and tip-apex distance (TAD) at latest followup in patients who had either standard or long nails.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a prospective randomized study comparing the use of a standard or long Proximal Femoral Nail-Antirotation™ (PFN-A; Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland; FDA-approved) to treat reverse obliquity type fractures of the trochanteric femoral region. During the 12-month period from January 2009 through December 2009, 40 patients who sustained a reverse oblique type trochanteric fracture were enrolled in the study at two university-based centers. During this period, we treated 173 patients with intertrochanteric fractures at the two centers. All patients with reverse oblique type (AO/OTA Type 31-A3 [16]) fractures were included in the study. We excluded 133 patients with AO/OTA 31-A1 to A2 fractures, pathologic fractures, previous proximal femoral fractures, and open fractures; patients with polytrauma who had an Injury Severity Score of greater than 16; and patients who had a severe concomitant medical condition (Grade V American Society of Anesthesiologists score). We then randomized patients into two groups using random allocation software [23]. Eighteen patients (Group 1) were treated with a 130°, standard PFN-A, which was 24 cm in length, and 22 patients (Group 2) were treated with a 130°, long PFN-A in variable lengths ranging from 34 to 42 cm. The patients were not blinded to their treatments. The mean age of all patients was 79 years (range, 67–95 years). All patients were followed up until fracture union or a revision operation was performed. No patient was lost to followup up to the end of first year. Seven patients (18%) died within 12 months of the operation, three in Group 1 and four in Group 2, leaving 33 patients for clinical study, 15 in the standard-nail group and 18 in the long-nail group. The minimum followup was 12 months in both groups (Group 1: average, 14 months; range, 12–19 months; Group 2, average, 14.5 months; range, 12–21 months).

We did not perform an a priori power analysis and consider this a pilot study. The groups were comparable with regard to all demographic and background data (Table 1). The two groups did not differ in terms of perioperative variables, except for operation and fluoroscopy times, which were longer (p < 0.001) in Group 2 (Table 1). The mean preoperative Parker-Palmer mobility scores were similar (p = 0.64) in the two groups: 7.3 ± 1.8 in Group 1 and 7.2 ± 1.7 in Group 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and perioperative data of patients with reverse oblique fractures of the proximal femur treated with standard or long proximal femoral nails

| Variable | Standard nail (n = 15) | Long nail (n = 18) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age (years)* | 78 (67–95) | 81 (73–89) | 0.255 |

| Sex (number of males/females) | 4/11 | 4/14 | 0.767 |

| Side (number on right/left) | 7/8 | 6/12 | 0.493 |

| Followup (months)* | 14 (12–18) | 15 (12–20) | 0.153 |

| Perioperative | |||

| Operation time (minutes)* | 52.6 (34–65) | 71.8 (57–94) | < 0.001 |

| Fluoroscopy time (seconds)* | 58.6 (45–79) | 75.3 (56–103) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital stay (days)* | 5.4 (2–11) | 4.9 (2–9) | 0.51 |

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses.

Patients were admitted to the emergency department after injury, and after stabilization of their systemic condition, they were transferred to the orthopaedic ward. Definitive surgery was performed as soon as possible but within 6 days after injury in all patients. Three experienced orthopaedic trauma surgeons (GO, NO, KA) performed all operative procedures. Patients were positioned supine on a radiolucent table. The choice of anesthetic method was made by the anesthesiologist. Closed reduction under C-arm control with manual traction and rotation of the injured extremity was performed in every patient in both groups before fixation. Afterwards, standard closed nailing and placement of blade and locking screws were performed by following the steps of the manufacturer-recommended technique. All nails were implanted without reaming. The nailing procedure did not start without obtaining a satisfactory reduction. Satisfactory reduction was defined as up to 10° of malalignment in any plane (varus, valgus, anteversion or retroversion) without any shortening, apposition, and rotational problems [25]. Every effort was made to place the helical blade of the nail as central as possible in two planes with its tip between 5 to 10 mm from the subchondral bone [5]. The standard PFN-A used in Group 1 had diameters of 10, 11, and 12 mm and a neck-shaft angle of 130°. The long PFN-A implanted in Group 2 had diameters of 9 and 10 mm and a neck-shaft angle of 130°. All nails were locked distally in static position with one 5-mm screw in Group 1 and two 5-mm screws in Group 2. No suction drain was used in any patient.

Postoperatively, all patients had antibiotic prophylaxis for 48 hours and deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis for 4 weeks. The postoperative rehabilitation protocol was identical for both groups. Patients were mobilized as soon as possible, usually on the second postoperative day with unrestricted weightbearing. Formal therapy was instituted, working on muscle strengthening, conditioning, and hip and knee ROM exercises.

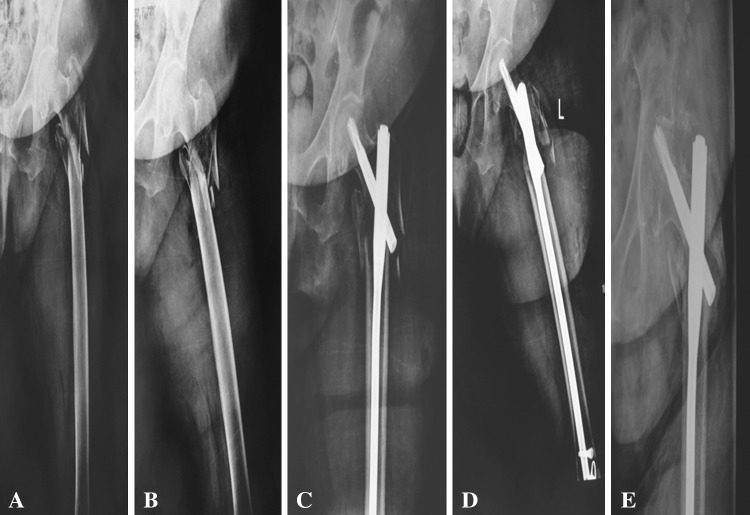

Patients were evaluated at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. Perioperative and postoperative data were recorded, including operating (from skin to skin) and fluoroscopy times. A colleague who was blinded to the groups and not involved in the treatment (SE) assessed walking ability at the end of first year from 0 to 9 using the mobility score of Parker and Palmer [21]. This score was calculated as the sum of the ability to walk indoors, walk outdoors, and participate in social activities of daily life. A value of 9 indicated no difficulty and a value of 0 indicated complete disability. Functional state and mobilization were also evaluated by the HHS [11] scaled from 1 to 100. Radiographs consisting of AP and lateral views of the hip and femur were obtained at the second postoperative day and every followup visit. Complications were noted prospectively and classified from Grade I to V according to Dindo et al. [7]. Superficial wound infection requiring only antibiotic therapy was classified as a Grade II complication. Deep infection requiring operative débridement under anesthesia and antibiotic administration was classified as a Grade IIIb complication. Fixation failure with loss of reduction was also considered Grade IIIb (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1A–E.

Images illustrate the case of a 74-year-old woman treated with a long PFN-A. Initial (A) AP and (B) lateral views show the left hip with a reverse obliquity fracture of the trochanteric region of the femur. (C) AP and (D) lateral views show the hip after fixation with a long PFN-A. (E) Perforation of the joint with the helical blade after 5 months is shown.

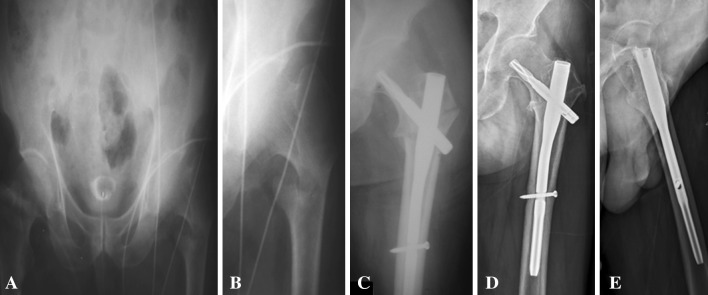

One of us (CO) not involved in surgical management of the patients evaluated the initial postoperative, every followup, and latest radiographs (Fig. 2). All radiographs were uploaded to a DICOM viewer software (Angora Viewer V.1.65; Datamed, Ankara, Turkey) that allows precise measurement of length and angles. First postoperative radiographs were compared to the radiographs obtained at latest followup on the same screen with this software. Change in the neck-shaft angle, migration of the blade, and TAD were measured digitally. Loss of fixation was defined as cut-out or penetration of the blade into the joint or nail breakage. Malunion was defined as angulation or rotational deformity of more than 10° or shortening of the limb of more than 1 cm when compared with the uninjured side [13]. Nonunion was defined as radiographic lucency around the implants, persistent fracture line that failed to show progressive healing after 9 months, loss of fixation, and pain associated with radiographic findings described above during walking at latest followup.

Fig 2A–E.

Images illustrate the case of a 76-year-old-man treated with a standard PFN-A. Initial AP views of the (A) pelvis and (B) left hip with a reverse obliquity fracture of the proximal femur are shown. (C) An AP view shows the hip after fixation with a standard nail. (D) AP and (E) lateral views of the hip after 12 months show bony union.

We used the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test to compare the proportions of the following variables between groups: sex, fracture side, fracture classification, union rate, and quality of reduction. Student’s t-test was used for determining any differences in age, operative and fluoroscopy times, and followup times between groups. We determined the differences in reoperation and 1-year mortality rates between groups using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. A Mann-Whitney rank-sum test was used to compare Parker-Palmer mobility scores and malunion rates between groups. The unpaired t-test was used to compare HHS and TAD [5] between groups. We performed statistical analyses using SPSS® Version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Two patients in Group 2 required a revision operation because of Grade IIIb complications: blade penetration into the joint in one and deep infection in the other. None of the patients required a revision operation in Group 1. We found no difference (p = 0.41) in reoperation rates between groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative data at 1-year followup after use of standard or long proximal femoral nails

| Postoperative outcome | Standard nail (n = 15) | Long nail (n = 18) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tip-apex distance (mm)* | 22 (14–31) | 24 (15–39) | 0.58 |

| Malunion (number of fractures) | 3 (20%) | 6 (33.3%) | 0.39 |

| Harris hip score (points; 1–100)* | 74 (61–88) | 79 (59–92) | 0.11 |

| Parker-Palmer mobility score (points)* | 5.2 (0–7) | 5.5 (0–7) | 0.53 |

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses.

We found no difference (p = 0.9) in 1-year mortality rate between Group 1 (16.6%) and Group 2 (18.1%).

At latest followup, mean Parker-Palmer mobility scores (Group 1: 5.2 ± 1.9; Group 2: 5.5 ± 1.7) and mean HHSs (Group 1: 74 ± 8; Group 2: 79 ± 10) were similar (p = 0.53 and p = 0.11, respectively) between groups (Table 2).

All fractures in both groups were united at latest followup. The rate of malunion was similar (p = 0.39) between groups: three patients (20%) in Group 1 and six patients (33.3%) in Group 2. There was no difference (p = 0.58) in mean TAD between groups: Group 1, 22 ± 5.2 mm and Group 2, 24 ± 6.5 mm (Table 2). The TAD measured 25 mm or less in 73% of the patients in Group 1 and 72% of the patients in Group 2.

One patient in Group 1 had a superficial wound infection (Grade II complication) that resolved with antibiotic therapy and wound care.

Discussion

SHSs are reliable fixation devices for treating most intertrochanteric fractures of the proximal femur [3, 24, 28] because of controlled impaction of the fracture to much more stable configuration during the postoperative period. This concept necessitates that the direction of impaction be perpendicular to the fracture line, which is present in most intertrochanteric fracture patterns [3, 14, 24]. However, reverse obliquity fractures are distinct from the other intertrochanteric fractures with respect to the direction of the major fracture line. The application of the concept of controlled impaction cannot be applied to reverse obliquity fractures because sliding of the proximal fragment and medialization of the distal fragment can lead to fracture distraction and subsequent loss of fixation. A number of investigators [17, 19, 20, 25] recommend treating reverse obliquity fractures with an IMN. Although there is a trend toward more frequent use of intramedullary fixation of intertrochanteric fractures, a number of authors have reported the use of IMNs for reverse obliquity fractures [3, 6, 8, 9, 12, 17–19, 25]. These authors suggest using IMNs for this fracture type because of fewer implant failures and high union rates. While some authors [8, 25, 26] report mobility scores, union rate, and revision rates of reverse obliquity fractures fixed with standard IMNs, the criteria for choosing a standard or long nail for the management are not stated clearly. We therefore compared (1) reoperation rate during the first postoperative year, (2) 1-year mortality rate, (3) Parker-Palmer mobility score and HHS, and (4) union rate and TAD in patients who had either a standard or long nail.

We recognize limitations to our study. First, we had a relatively small number of patients in each group. A larger sample size is required to ensure a representative distribution of the population and to be considered representative of groups of patients to whom results will be generalized. However, the incidence of reverse obliquity intertrochanteric fractures is low. As we did not perform a priori power analysis to calculate the required sample and effect size, we consider our study a pilot study to allow subsequent power analyses. Second, the surgeons were not blinded throughout the study and rather informed patients before surgery about the implant that would be used. However, the evaluator was blinded to the treatment. Third, approximately 1/5 of the patients could not be evaluated at the end of first year because of mortality. We obviously had no followup data on these patients and there is a possibility that we did not identify patients who would have had evidence of implant failure or malunion if radiographs had been possible.

The reoperation rate in our study was comparable with those of other studies in the literature (Table 3). Min et al. [17] reported 22 reverse obliquity fractures among 635 fractures treated with either a standard proximal femoral nail (PFN) or a Gamma® nail. Three patients in the Gamma® nail group had major revision procedures. Only one patient in the PFN group had a revision procedure. In another study [25], 55 fractures were fixed with standard PFNs and 48 with Gamma® nails. Although statistically not different, reoperation rate was slightly higher in the PFN group (18.4%) than in the Gamma® nail group (12.2%). Honkonen et al. [12] reported 72 reverse obliquity fractures of the trochanteric region treated with cephalomedullary nails. The overall reoperation rate was 8.3% (six patients). In another study [19], 40 patients treated with either PFN or intertrochanteric-subtrochanteric nails were reported. Fixation failures occurred in four fractures with posteromedial defects all in the PFN group. Although their study was not randomized, they suggested fractured lesser trochanteric fragments and posteromedial defects were negative signs for failures. In our series, there were two reoperations (in Group 2) because of deep infection in one and implant failure in the other.

Table 3.

Outcome after surgical treatment of AO/OTA 31-A3 proximal femur fractures

| Study | Study design | Treatment | Number of fractures | Mean followup (months) | Reoperation/ failure of fixation rate (%) | Mortality rate (%) | Functional score (points) (at latest followup) | Union rate (%) | TAD (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haidukewych et al. [10] | RCS | SHS, DCS, CMN, BP | SHS: 16 DCS: 10 CMN: 6 BP: 15 |

18 | 32 | 19 (1st year) | NR | SHS: 44 DCS: 70 CMN: 80 BP: 87 |

NR |

| Sadowski et al. [22] | RCT | DCS vs PFN | DCS: 19 PFN: 20 |

13 | DCS: 35 PFN: 0 |

8 (1st year) | DCS: 6 (PMS) PFN: 5 (PMS) |

DCS: 59 PFN: 94 |

NR |

| Hohkonen et al. [12] | RCS | CMN | 72 | 5 | 8 | 18 (3nd month) | NR | 99 | NR |

| Park et al. [19] | RCS | CMN | 40 | 6 | 10 | 9 (6th month) | Recovered to preinjury level in 65% | 90 | < 20 |

| Willoughby [28] | RCS | SHS | 35 | NR | 11 | 24 (time NR) | NR | 91 | NR |

| Min et al. [17] | RCS | GN vs PFN | GN: 11 PFN: 11 |

18 | GN: 27 PFN: 9 |

0 (1st year) | 73% excellent and good outcomes in both groups (SWS) | GN: 91 PFN: 100 |

28 |

| Elis et al. [8] | RCS | DCS vs EPFN | DCS: 14 EP N: 19 |

28 | DCS: 14 EPFN: 11 |

24 (time NR) | DCS: 60 (HHS) EPFN: 69 (HHS) DCS: 3 (PMS) EPFN: 5 (PMS) |

DCS: 93 EPFN: 100 |

NR |

| Schipper et al. [25]* | RCT | PFN vs GN | PFN: 211 GN: 213 |

NR | PFN: 18 GN: 12 |

PFN: 25 GN: 24 |

PFN: 67 (HHS) GN: 70 (HHS) |

PFN: 92 GN: 91 |

NR |

| Current study | RCT | Long vs standard PFN-A | Standard: 15 Long: 18 |

14 | Standard: 0 Long: 11 |

Standard: 17 Long: 18 (1st year) |

Standard: 74 (HHS) Long: 79 (HHS) Standard: 5 (PMS) Long: 6 (PMS) |

Standard: 100 Long: 100 |

Standard: 22 Long: 24 |

* The only study that includes AO/OTA 31.A2 and A3 fractures; TAD = tip-apex distance; RCS = retrospective case series; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SHS = sliding hip screw; DCS = dynamic condylar screw; CMN = cephalomedullary nail; BP = blade plate; PFN = proximal femoral nail; GN = Gamma® nail; EPFN = expandable PFN; PFN-A = Proximal Femoral Nail-Antirotation™; NR = not reported; PMS = Parker-Palmer mobility score; SWS = Salvati and Wilson score; HHS = Harris hip score.

We found no difference in 1-year mortality rates between two groups and the overall 1-year mortality rate was 18%, which is comparable with those in other studies. One-year mortality rate after unstable intertrochanteric fracture varies between 11% and 27% in the literature [3, 8, 10, 25].

The overall mean Parker-Palmer mobility score and HHS in our series were 5.3 and 76, respectively. The mean scores did not differ between groups. Postoperative function in patients with reverse obliquity fractures have been reported in a number of studies [8, 12, 18, 19, 25] (Table 3). Functional scores were similar for PFN and Gamma® nails in 103 patients with reverse obliquity fractures [25]. In a small single-cohort retrospective study [18], 13 of 15 patients had “excellent” or “good” HHSs (the authors did not provide raw data on the scores). Elis et al. [8] reported 33 patients treated with either expandable PFNs or 95° dynamic condylar screw plates. They found better functional scores in the expandable-nail group.

We found all fractures of surviving patients in both groups united at latest followup. The malunion rates and average TAD were similar. The union rate of reverse obliquity fractures managed with cephalomedullary nails is reportedly between 80% and 100% in the literature (Table 3). The lowest union rate (80%) was reported by Haidukewych et al. [10]. They reported the outcome of only six patients treated with cephalomedullary nails. The very limited patient group in this study might not accurately reflect the real population. The union rates among subgroups of reverse obliquity fractures were reported by Park et al. [19]. Union time was prolonged and union rate was low in 31-A3.3 fractures compared with 31-A3.1 or 3.2 fractures. In our study, the only patient who had a reoperation due to implant failure also had a 31-A3.3 fracture.

In conclusion, long nails offer no clinical advantage compared to standard nails for the treatment of reverse obliquity fractures of the trochanteric region. Long nails do not appear to have higher union rates or lower reoperation rates than standard nails. Functional scores were also similar. The greater operative and fluoroscopy times when using long nails compared to standard nails may not justify their use for treating reverse obliquity fractures in the elderly with more severe medical comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Serkan Erkan MD for his meticulous efforts in the collection and organization of patients’ walking ability data.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Celal Bayar University (Manisa, Turkey) and Ege University (Izmir, Turkey).

References

- 1.Banan H, Al-Sabti A, Jimulia T, Hart AJ. The treatment of unstable extracapsular hip fractures with AO/ASIF proximal femoral nail (PFN)—our first 60 cases. Injury. 2002;33:401–405. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barquet A, Francesescoli L, Rienzi D, Lopez L. Intertrochanteric-subtrochanteric fractures: treatment with the long Gamma nail. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:324–328. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton TM, Gleeson R, Topliss C, Greenwood R, Harries WJ, Chesser TJS. A comparison of the long Gamma nail with sliding hip screw for the treatment of AO/OTA 31–A2 fractures of the proximal part of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:792–798. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgaertner MR, Curtin SL, Lindskog DM. Intramedullary versus extramedullary fixation for the treatment of intertrochanteric hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;348:87–94. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199803000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumgaertner MR, Curtin SL, Lindskog DM, Keggi JM. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1058–1064. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorgul K, Reikeras O. Outcome after treatment complications of Gamma nailing: a prospective study of 554 trochanteric fractures. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:231–235. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elis J, Chechik O, Maman E, Steinberg EL. Expandable proximal femoral nails versus 95° dynamic condylar screw-plates for the treatment of reverse oblique intertrochanteric fractures. Injury. 2012;43:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forte ML, Virnig BA, Kane RL, Durham S, Bhandari M, Feldman R, Swiontkowski MF. Geographic variation in device use for intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:691–699. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haidukewych GJ, Israel TA, Berry DJ. Reverse obliquity fractures of the intertrochanteric region of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:643–650. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honkonen SE, Vihtonen K, Jarvinen MJ. Second generation cephalomedullary nails in the treatment of reverse obliquity intertrochanteric fractures of the proximal femur. Injury. 2004;35:179–183. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kregor PJ, Obremskey WT, Kreder HJ, Swiontkowski MF. Unstable pertrochanteric femoral fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:63–66. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200501000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyle RF, Gustilo RB, Premer RF. Biomechanical analysis of the sliding characteristics of compression hip screws. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:1308–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahomed N, Harrington I, Kellam J, Maistrelli G, Hearn T, Vroemen J. Biomechanical analysis of the Gamma nail and sliding hip screw. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;304:280–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, Broderick JS, Creevy W, DeCoster TA, Prokuski L, Sirkin MS, Ziran B, Henley B, Audige L. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium-2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:S1–S133. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200711101-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min WK, Kim SY, Kim TK, Lee KB, Cho MR, Ha YC, Koo KH. Proximal femoral nail for the treatment of reverse obliquity intertrochanteric fractures compared with Gamma nail. J Trauma. 2007;63:1054–1060. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000240455.06842.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozkan K, Eceviz E, Unay K, Tasyikan L, Akman B, Eren A. Treatment of reverse oblique trochanteric femoral fractures with proximal femoral nail. Int Orthop. 2011;35:595–598. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1002-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SY, Yang KH, Yoo JH, Yoon HK, Park HW. The treatment of reverse obliquity intertrochanteric fractures with intramedullary hip nail. J Trauma. 2008;65:852–857. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802b9559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker MJ, Handoll HH. Gamma and other cephalocondylic intramedullary nails versus extramedullary implants for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD000093. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Parker MJ, Palmer CR. A new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:797–798. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadowski C, Lübbeke A, Saudan M, Riand N, Stern R, Hoffmeyer P. Treatment of reverse oblique and transverse intertrochanteric fractures with use of an intramedullary nail or a 95 degrees screw-plate: a prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:372–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saghaei M. Random allocation software. Version 1.0.0. Available at: http://mahmoodsaghaei.tripod.com/Softwares/dnld/RA.zip. Accessed January 19, 2005.

- 24.Saudan M, Lübbeke A, Sadowski C, Riand N, Stern R, Hoffmeyer P. Pertrochanteric fractures: is there an advantage to an intramedullary nail? A randomized, prospective study of 206 patients comparing the dynamic hip screw and proximal femoral nail. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:386–393. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schipper IB, Steyerberg EW, Castelein RM, Van der Heijden FH, Den Hoed PT, Kerver AJ, Van Vugt AB. Treatment of unstable trochanteric fractures: randomized comparison of the Gamma nail and the proximal femoral nail. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Utrilla AL, Reig JS, Munoz FM, Tufanisco CB. Trochanteric gamma nail and compression hip screw for trochanteric fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:229–233. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000151819.95075.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weller I, Wai EK, Jaglal S, Kreder HJ. The effect of hospital type and surgical delay on mortality after surgery for hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:361–366. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willoughby R. Dynamic hip screw in the management of reverse obliquity intertrochanteric neck of femur fractures. Injury. 2005;36:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]