Abstract

Through processing peptide and protein C termini, carboxypeptidases participate in the regulation of various biological processes. Few tools are however available to study the substrate specificity profiles of these enzymes. We developed a proteome-derived peptide library approach to study the substrate preferences of carboxypeptidases. Our COFRADIC-based approach takes advantage of the distinct chromatographic behavior of intact peptides and the proteolytic products generated by the action of carboxypeptidases, to enrich the latter and facilitate its MS-based identification. Two different peptide libraries, generated either by chymotrypsin or by metalloendopeptidase Lys-N, were used to determine the substrate preferences of human metallocarboxypeptidases A1 (hCPA1), A2 (hCPA2), and A4 (hCPA4). In addition, our approach allowed us to delineate the substrate specificity profile of mouse mast cell carboxypeptidase (MC-CPA or mCPA3), a carboxypeptidase suggested to function in innate immune responses regulation and mast cell granule homeostasis, but which thus far lacked a detailed analysis of its substrate preferences. mCPA3 was here shown to preferentially remove bulky aromatic amino acids, similar to hCPA2. This was also shown by a hierarchical cluster analysis, grouping hCPA1 close to hCPA4 in terms of its P1 primed substrate specificity, whereas hCPA2 and mCPA3 cluster separately. The specificity profile of mCPA3 may further aid to elucidate the function of this mast cell carboxypeptidase and its biological substrate repertoire. Finally, we used this approach to evaluate the substrate preferences of prolylcarboxypeptidase, a serine carboxypeptidase shown to cleave C-terminal amino acids linked to proline and alanine.

Carboxypeptidases (CPs)1 catalyze the release of C-terminal amino acids from proteins and peptides (1, 2), and are grouped according to the chemical nature of their catalytic site. Accordingly, there are three types of carboxypeptidases: metallocarboxypeptidases (MCPs), serine carboxypeptidases (SCPs), and cysteine carboxypeptidases. CPs can also be classified based on their substrate specificity; CPs that prefer hydrophobic C-terminal amino acids (A-like MCPs or C-type SCPs), those that cleave C-terminal basic residues (B-like MCPs or D-type SCPs), those that recognize substrates with C-terminal aspartate or glutamate residues, and other CPs that display a broad substrate specificity (3, 4).

CPs were initially considered as degrading enzymes associated with protein catabolism. However, accumulating evidence demonstrates that some CPs are (more) selective and play key roles in controlling various biological processes (2, 5). Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a MCP homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) that belongs to the M2 family of proteolytic enzymes according to the MEROPS classification, is a potent negative regulator of the renin-angiotensin system and plays a key role in maintaining blood pressure homeostasis. ACE2 cleaves off a C-terminal phenylalanine thereby converting angiotensin II to the heptapeptide angiotensin-(1–7), a peptide hormone that opposes the vasoconstrictor and proliferative actions of angiotensin II (6). Cathepsin A, a lysosomal SCP, is also believed to function in blood pressure regulation, in this case through its action against vasoactive peptides like endothelin-1 or angiotensin I (7). Human carboxypeptidase A4 (hCPA4), a MCP from the M14 family, presumably functions in neuropeptide processing and was linked to prostate cancer aggressiveness (8).

Besides their biological importance, CPs are also exploited in biotechnological and biomedical applications. Carboxypeptidase B (CPB) for instance, is a M14 MCP used for manufacturing recombinant human insulin. Recombinant preproinsulin is enzymatically processed in vitro by pancreatic trypsin and carboxypeptidase B to generate the active insulin form (9). Further, carboxypeptidase digestion has been used for determining the C-terminal sequence of purified proteins or peptides. The most popular CPs being the SCPs C, P and Y (10). In addition, the food industry uses different SCPs to process protein products to reduce their bitter taste (11–13).

Identifying a protease's specificity and its natural substrates provides key information to understanding the molecular role of proteases (14, 15). Moreover, determination of a protease's specificity also provides a framework for the design of selective probes and potent and selective inhibitors (16). Although several factors impact on substrate selection, a key factor is the complementarity of a protease binding site with specific substrate side-chains.

Several approaches for determining protease substrate specificity based on peptide libraries have been developed, including substrate phage/bacterial display libraries, peptide microarrays, positional-scanning peptide libraries, mixture-based peptide libraries, and proteome-derived peptide libraries (17). The latter were more recently introduced by Schilling et al. (18) and make use of natural peptide libraries generated by proteolysis of a model proteome using a specific protease (e.g. trypsin, chymotrypsin). Such peptide libraries are subsequently digested by a protease of interest and the resulting neo-N-terminal products are enriched and identified following LC-MS/MS analyses. This technology allows profiling of the substrate specificity of endoproteases and aminopeptidases. However, viewing the fact that only C-terminal cleavage products are isolated by this method, it cannot be used to study CPs because their resulting primed site cleavage products are typically only a single amino acid and thus are not compatible for subsequent LC-MS/MS based identification.

Currently, two different peptide-centric degradomic approaches (19) are available for CP substrate profiling. Recently, a multiplex substrate profiling by mass spectrometry (MSP-MS) method, which applies mass spectrometry-based peptide sequencing to detect cleavage products in a mixture of synthetic peptides, was used to determine the substrate preferences of prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP) (20). Further, peptidomic studies have made use of natural peptides isolates from cells and tissues as natural substrate pools to test cleavages by CPs (8, 21, 22). In this list of degradomic approaches, we can additionally consider the protein-centric positional proteomics approaches; C-terminal COFRADIC (23) and C-TAILS (24), capable of identifying in vivo CP proteolytic events, based on the identification of protein neo-C termini.

We here exploited the COFRADIC technology (25) and developed a proteome-derived carboxypeptidase peptide library assay that was used to determine the substrate specificity profile of 5 selected human carboxypeptidases: 4 enzymes belonging to the MCP family and PRCP, which is a SCP. Given that MCPs are the most studied and thus a highly relevant group of CPs, the human metallocarboxypeptidases A4 (hCPA4), A2 (hCPA2), and A1 (hCPA1) were used as model CPs. Two different peptide libraries, created using chymotrypsin or metalloendopeptidase Lys-N as peptide library generating proteases, were used to extensively profile the proteolytic substrate specificities of these MCPs. In addition, we profiled the substrate preferences for the yet uncharacterized mast cell carboxypeptidase (MC-CPA or mCPA3). Besides, using Lys-N proteome-derived peptide libraries and making use of shorter protease incubation times, information on sequential cleavages of these enzymes could be obtained. Finally, this assay was additionally applied to PRCP, a pharmaceutically relevant SCP that differs from MCPs in its enzymatic characteristics, further demonstrating the more universal applicability of our method.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Human K-562 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CCL-243, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and cultured in GlutaMAX™ containing RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Protein Production and Purification

The human carboxypeptidases A1 (hCPA1), A2 (hCPA2) and A4 (hCPA4) were obtained as recombinant proteins using the pPIC9 expression vector and the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris as an expression host. Enzyme purifications were performed as described previously (26–28). These enzymes were purified in their zymogen form and the active enzymes were obtained through tryptic activation (at a 1/50 (w/w) ratio) for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting mature and activated enzymes were subsequently purified by anion-exchange chromatography (TSK-DEAE 5PW) on a FPLC-Äkta system using a linear salt gradient (ranging from 0 to 30% of 0.4 m ammonium acetate in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 9.0). Eluted fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the purest fractions containing the enzyme were pooled, desalted, and concentrated to 1 mg/ml by Amicon centrifugal filter devices (Ultra 0.5 ml 10 kDa MWCO columns (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA)).

Mouse CPA3 (mCPA3) was purified from mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) (kindly provided by Dr Gunnar Pejler, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences) using a two-step purification procedure. Mast cells were lysed in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 4 m NaCl, 0.1% PEG 3350 supplemented with a Complete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Mixture Tablet (Roche Diagnostics) (buffer A) for 30 min at 4 °C. The lysate was subsequently centrifuged and the supernatant was diluted twenty-fold in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 and 100 mm NaCl, supplemented with a Complete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Mixture Tablet (buffer B). The diluted extract was loaded on a Heparin HyperD® M column (Pall Biosepra, Cergy-Saint-Christophe, France) equilibrated with buffer B. mCPA3 was eluted using 5 volumes of buffer A. The eluate was concentrated on Amicon centrifugal filters devices, and fractionated on a Superdex 75 column in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 m NaCl and 0.025% PEG 3350. The purest eluted fractions (analyzed by SDS-PAGE) showing the highest activity toward N-(4-methoxyphenylazoformyl)-Phe-OH (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland) were pooled and concentrated by Amicon centrifugal filters devices (Ultra 0.5 ml 10 kDa MWCO columns, Millipore).

Preparation of Proteome-derived Peptide Libraries

Proteome-derived peptide libraries were generated from human K-562 cell extracts. Cells were repeatedly (3×) washed in digestion buffer (50 mm NH4CO3, pH 7.9) and re-suspended in this buffer at 2 × 107 cells per ml. Then, these cell suspensions were subjected to three rounds of freeze-thaw lysis and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation for 10 min at 16,000 × g at 4 °C. To prepare the chymotryptic and metalloendopeptidase Lys-N proteome-derived peptide libraries, the lysates were respectively digested for 4 h at 37 °C using sequencing-grade chymotrypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1/200 (w/w) or recombinant Lys-N (1/85, w/w) for two hours at 37 °C (U-Protein Express BV, Utrecht, The Netherlands). To stop proteolytic digestion, acetic acid was added to a 4% final concentration.

Peptide Library-based Carboxypeptidase Assay

For the chymotryptic peptide library and to prevent oxidation of methionines between the primary and secondary RP-HPLC runs, methionines were oxidized before the primary run. The methionine oxidation reaction proceeded in the injector compartment by transferring 20 μl of a freshly prepared aqueous 3% H2O2 solution to a vial containing 90 μl of the acidified peptide mixture (final concentration of 0.54% H2O2). This reaction proceeded for 30 min at 30 °C after which the sample was immediately injected onto the RP-HPLC column. No prior methionine oxidation was performed when the Lys-N peptide libraries were assayed (see “Results”). From these mixtures, 100 μl (equivalent to ∼350 μg of digested proteins) was injected onto a RP-column (Zorbax 300SB-C18 Narrow Bore, 2.1 mm internal diameter (I.D.) x 150 mm length, 5 μm particles; Agilent Technologies) for the first RP-HPLC run. Following 10 min isocratic pumping with solvent A (10 mm ammonium acetate in water/acetonitrile (98/2, v/v), pH 5.5), a gradient was started of 1% solvent B (10 mm ammonium acetate in water/acetonitrile (30/70, v/v), pH 5.5) increase per minute. The column was then run at 100% solvent B for 5 min, switched to 100% solvent A and re-equilibrated for 20 min with solvent A. The flow was kept constant at 80 μl/min using Agilent's 1100 series capillary pump with an 800 μl/min flow controller. Twenty fractions of 2 min intervals (from 20 to 60 min after sample injection) and 26 fractions (from 20 to 72 min after sample injection) were collected for the chymotryptic library and the Lys-N library respectively.

Each peptide fraction was dried and re-dissolved in 20 μl of CP-supplemented assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 and 100 mm NaCl prepared with 90% H218O water (Cambridge Isotope Labs, Andover, MA, USA) containing 7.3 units of MCP per ml (which is approximately equivalent to a 10 nm CP concentration)). Note that one unit of MCP activity was defined as the amount of enzyme hydrolyzing 1 nmol of N-(4-methoxyphenylazoformyl)-l-phenylalanine substrate per min at 37 °C. For PRCP (BPS Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), a 5 nm final assay concentration was used. CP hydrolysis was allowed to proceed for 2 h at 37 °C and stopped by addition of 33 μl of 4% acetic acid in solvent A. All 20 (chymotryptic library) or 26 (Lys-N library) samples were reloaded on the same RP-column and separated using identical conditions. Per sample, twenty secondary “shifted” fractions of 1 min wide were collected in a time interval ranging from 21 to 1 min before the fraction collection interval (but eluting the earliest at 10 min (start of the gradient)) used for the primary fraction. Whenever the “nonshifted” fractions were additionally analyzed, six extra 1 min wide fractions were collected in a time interval ranging from 1 min before to 3 min after the original fraction collection interval. All peptide fractions were dried and, secondary fractions eluting 4 min apart were pooled by re-dissolving these in a final volume of 20 μl of 2 mm TCEP and 2% acetonitrile, similar to a pooling strategy described previously (29). In total, 40 (when shifted fractions were analyzed alone) or 52 (in the case the extra “nonshifted” fractions were additionally analyzed) peptide fractions per setup were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using an Ultimate 3000 RSLC nano LC-MS/MS system (Dionex, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) in-line connected to a LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Fisher, Bremen, Germany). 2 μl of the sample mixture was first loaded on a trapping column (made in-house, 100 μm I.D. × 20 mm length, 5 μm Reprosil-Pur Basic-C18-HD beads, Dr. Maisch, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany). After back-flushing from the trapping column, the sample was loaded on a reverse-phase column (made in-house, 75 μm I.D. × 150 mm length, 3 μm C18 Reprosil-Pur Basic-C18-HD beads). Peptides were loaded with solvent A' (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in 2% acetonitrile) and were separated with a linear gradient from 98% of solvent A″ (0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile) to 50% of solvent B' (0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile) with a linear gradient of a 1.8% solvent B' increase per minute at a flow rate of 300 nl/min followed by a steep increase to 100% of solvent B′. The Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent mode, automatically switching between MS and MS/MS acquisition for the ten most abundant peaks in a MS spectrum. Full scan MS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap at a target value of 1E6 with a resolution of 60,000. The ten most intense ions were then isolated for fragmentation in the linear ion trap, with a dynamic exclusion of 20 s. Peptides were fragmented after filling the ion trap at a target value of 1E4 ion counts. From the MS/MS data in each LC run, Mascot Generic Files were created using the Mascot Distiller software (version 2.3.2.0, Matrix Science, www.matrixscience.com/Distiller.html). Although generating these peak lists, grouping of spectra was allowed with maximum intermediate retention time of 30 s and maximum intermediate scan count of 5. Grouping was done with a 0.005 Da precursor tolerance. A peak list was only generated when the MS/MS spectrum contained more than 10 peaks. There was no de-isotoping and the relative signal-to-noise limit was set at 2. The generated MS/MS peak lists were then searched with Mascot using the Mascot Daemon interface (version 2.3, Matrix Science). The Mascot search parameters were set as follows. Searches were performed in the Swiss-Prot database with taxonomy set to human (either the 2011_05, 2011_06 or 2013_01 UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database release containing respectively 20,286, 20,312 and 20,307 human protein sequence entries were used). Single 18O modification of peptide C termini, acetylation of protein N termini and pyroglutamate formation of N-terminal glutamine were set as variable modifications. Methionine oxidation to methionine-sulfoxide was set as fixed modification for the chymotryptic library assays and as a variable modification for the Lys-N library assays. For the chymotryptic library the enzyme was set to “none” (because up to 3 missed cleavages could be detected), whereas for the Lys-N library a semi-Lys-N/P (semi Lys-N specificity with lysine-proline cleavage allowed) was set as enzyme allowing for one missed cleavage. The mass tolerance on the precursor ion was set to 10 ppm and on fragment ions to 0.5 Da. The peptide charge was set to 1+, 2+ or 3+ and the instrument setting was put on ESI-TRAP. Only peptides that were ranked one and scored above the threshold score, set at 95% confidence, were withheld. According to the method described by Käll et al. (30), the false discovery rate was estimated and was found <2% at the spectrum level and <3% at the peptide level. Identified MS/MS spectra are available on-line in the PRoteomics IDEntifications database (PRIDE) (31) under the project entitled “Proteome-derived peptide libraries to study the substrate specificity profiles of carboxypeptidases” under the accessions 26851–26859, 27075–27076 and 28756–28757.

Post-analysis of the LC-MS/MS Data

Primed side residues of the full-length peptidic substrates were inferred using an in-house java-based script named PeptideRetriever. This command-based tool maps the identified peptides onto a database of choice in a protein accession dependent manner, enabling extraction of protein-matching N- and/or C-terminal residues. Unless stated otherwise, we only considered the ultimate products of cleavage (i.e. we assumed that only one amino acid was released), as inferred from the database and, to reconstruct the sequence of the original peptide substrates, the proteolytically removed primed side residue was added to the C terminus of the identified peptide (Fig. 1B). All identified 18O-labeled proteolytic products were considered for the analysis.

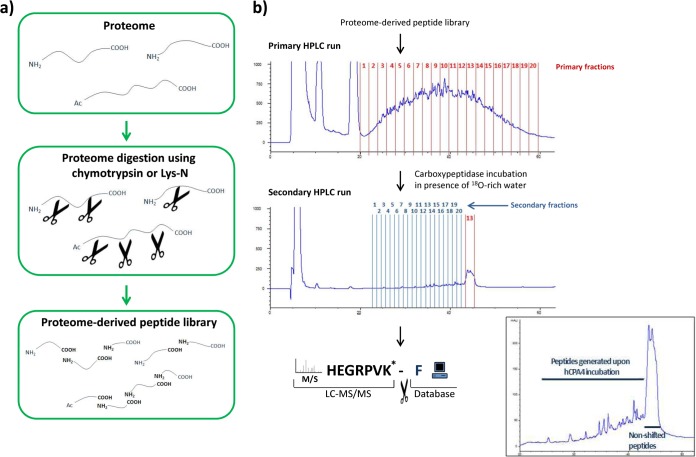

Fig. 1.

Proteome-derived peptide library generation and carboxypeptidase substrate screen. A, Peptide library generation workflow. Peptide libraries are generated from whole proteomes by digestion using a peptide library-generating protease (e.g. chymotrysin or Lys-N). Ac- is indicative of N-terminal protein acetylation in vivo. B, Chymotryptic proteome-derived peptide library-based carboxypeptidase substrate screen. The peptide library is separated by reverse-phase HPLC (primary COFRADIC run) and collected in 20 primary fractions. Each dried fraction is reconstituted in a CP compatible buffer prepared in 95% 18O-rich water and incubated with the CP of interest (i.e. hCPA4 in this case). These altered primary fractions are then re-separated on the same column using identical conditions (secondary COFRADIC run). The shifted carboxypeptidase products are collected in 1 min fractions (secondary fractions) starting from 21 to 1 min before the elution time of the primary collection interval containing the unaltered peptides. The CP products contain a C-terminal 18O-label (here indicated with an asterisk) and can therefore be distinguished from their C-terminal unmodified counterparts following LC-MS/MS analyses and database searching. The cleaved C-terminal amino acid is subsequently inferred from the database. The inset displays a detailed zoom of a secondary COFRADIC run and shows that hydrophilic shifts were observed on hCPA4 mediated C-terminal amino acid release.

Sequence specificity profiles were generated using iceLogo (32) using percent difference as scoring system. This scoring method uses the difference in frequency for an amino acid in the experimental set and the reference set as a measure of the height of a letter in the amino acid stack. Only significantly under- and over-represented amino acids are visualized at each position. Icelogo compares the amino acid frequencies in the positive set with the frequencies in the reference set. An amino acid will be regulated if the Z-score is not a part of the condence interval defined by a p value p ≤ 0.01 in all the cases. The Z-score is calculated with the formula:

|

where X and μ are the frequency of a specific amino acid on a specific position in the positive set and reference set, respectively, and σ the standard deviation. Further details on the statistics can be found at http://iomics.ugent.be/icelogoserver/manual.pdf.

Comparative Modeling of mCPA3

The protein structure modeling of the active domain of mCPA3 was obtained from computational prediction using the I-TASSER server (33, 34). The confidence level of the models was evaluated by the C-score (1.64 for the model) and the TM-score (0.94 ± 0.05) (33, 34). The model with a hexapeptide in the active site was derived from the structure of hCPA4 with PDB ID code 2PCU (35) in which the amino acid in the P1′ position was mutated to Trp. Molecular visualizations were performed using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

RESULTS

Proteome-derived Peptide Library Generation and Carboxypeptidase Assay Workflow

To profile the substrate specificity of CPs, we opted for the use of proteome-derived peptide libraries, which should allow comprehensive analyses of protease preferences (18). Fig. 1 shows both the peptide library generation strategy and the assay workflow. In this approach, proteome preparations from human K-562 cells were used as starting material, and peptide libraries were generated by proteolysis using either chymotrypsin (cleaves C-terminal of Tyr, Phe, Leu and Met) or metalloendopeptidase Lys-N (cleaves N-terminal of Lys). The resulting peptide mixtures were subsequently used to assay the substrate specificity profiles of carboxypeptidases.

Combined fractional diagonal chromatography (COFRADIC) relies on the principle of diagonal reversed-phase chromatography to select a representative set of peptides (25). A modification step (chemical or enzymatic reaction) is performed between two consecutive, identical chromatographic separations to infer different chromatographic properties to modified peptides, thereby allowing for their isolation. Here, CPs act as peptide modifiers, reducing the length of their respective substrates (by cleaving off a C-terminal residue) and thus altering their chromatographic properties.

The generated peptide library was first fractionated by RP-HPLC, after which each primary fraction was subjected to CP treatment in assay buffers prepared with 18O-rich water. Then, each CP-modified primary fraction was re-separated using identical RP-HPLC conditions. Fig. 1B shows the chromatograms of a typical primary and secondary COFRADIC run (here the primary fraction eluting between 44 and 46 min was treated with hCPA4). Judged from initial tests, a hydrophilic shift was expected for CPA substrates. Consequently, CP peptide products were collected in 20 fractions of 1 min wide intervals, each time starting 21 min before the elution of CP-unmodified peptides (shifted fractions). An analysis of nonshifted fractions for hCPA1 showed that only 0.13% (or 2 of 1504 peptides identified) of all hCPA1 products identified were found in these fractions, supporting analysis of the shifted fractions only.

Given that proteolysis is the hydrolytic cleavage of peptide bonds, we exploited carboxypeptidase-induced 18O-labeling at the C terminus of CP-generated peptides. Following LC-MS/MS analysis and database searching, this 18O-label helps in identifying genuine oligopeptide products of CP-mediated proteolysis. Indeed, 18O-labeling indicates that at least one amino acid was released from the C terminus of the identified peptide (i.e. a sequential removal of more than one amino acid might occur in some cases). When delineating the substrate specificity profiles and during reconstruction of the original substrates being cleaved we considered that only one C-terminal amino acid was removed (Fig. 1B). The sequential release of two or more amino acids from its substrate can easily be deduced for the Lys-N libraries (in contrast to the chymotrypsin libraries), because of the more stringent substrate specificity of Lys-N.

The Substrate Specificity Profile of Human Carboxypeptidase A4

First, we mainly focused on profiling the substrate specificity profiles of members of the M14 family of metallocarboxypeptidases, one of the most distributed and varied groups of CPs. Using proteome-derived chymotrytic peptide libraries, we first assayed the previously characterized human carboxypeptidase A4 (8, 23). We identified 9729 18O-labeled hCPA4 products, representing 93% of all isolated peptides, thus pointing to a very efficient COFRADIC-based enrichment. From these peptides, the C-terminal amino acid cleaved off was inferred by database searching, which allowed determining the substrate preference of hCPA4. Note that the specificity determinants of MCPs are here described according to the model of Schechter & Berger (36) in which each specificity subsite in the protease is able to accommodate the side-chain of a single amino acid residue in the substrate. The amino acids surrounding a MCP cleavage site are indicated as … -P3-P2-P1↓P1′, with the residue C-terminal to the scissile bond being the primed side residue (P1′). The hCPA4 substrate specificity profile obtained by analyzing the hCPA4-treated proteome-derived chymotryptic peptide library, is shown as an iceLogo (32) and as a heat map (Figs. 2A and 2B). For generating such iceLogos and heat maps, the frequency of amino acid occurrence at each position in hCPA4 substrates was compared with the amino acid occurrence found in the chymotryptic peptide library reference set. LC-MS/MS analysis of a representative subset of the original peptide library input, identified 909 peptides and revealed that chymotrypsin generates a library composed of peptides mainly ending with Tyr, Leu, Phe or Met, although up to three missed cleavages could be observed (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S1). Importantly, to create representative enzyme substrate specificity profiles using iceLogo, the reference set was used to correct for the bias introduced by the amino acid composition of the peptide library. The hCPA4-derived specificity profile reveals that the P1′ position is the major specificity determinant for this M14 CP, and that amino acids at the P1 position also contribute to the substrate specificity. hCPA4 shows a preference for aliphatic and aromatic hydrophobic amino acids at P1′ (Fig. 3). At the P1 position, basic and hydrophobic amino acids are preferred, whereas acidic amino acids, Thr, and Gly are disfavored and Pro is even absent at this position (supplemental Fig. S2).

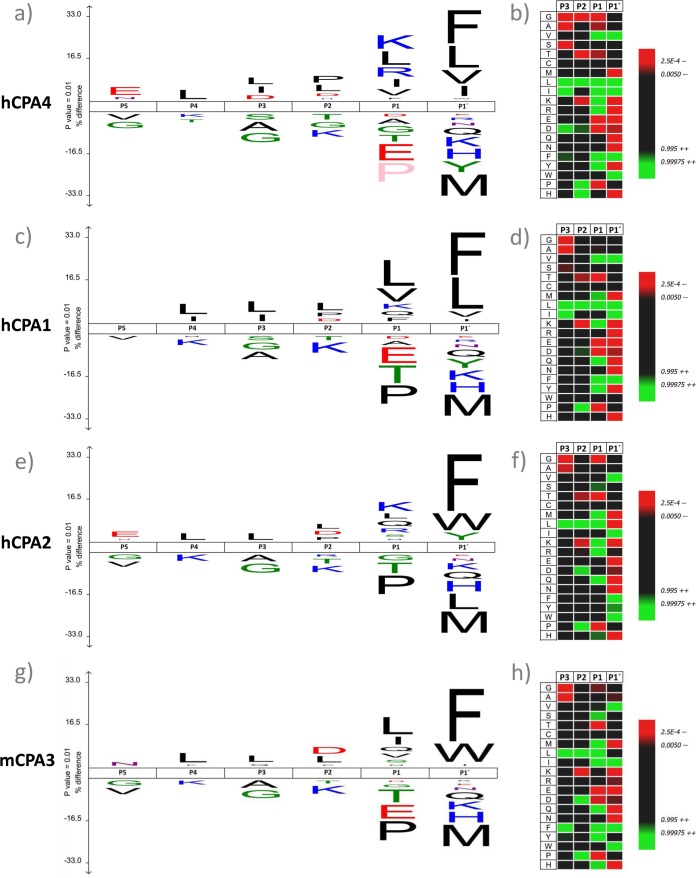

Fig. 2.

Substrate specificity profiles of hCPA4, hCPA1, hCPA2, and mCPA3 using a chymotryptic proteome-derived peptide library. IceLogo and heat map representations of the substrate peptide sequences for hCPA4 (A and B respectively), hCPA1 (C, D), hCPA2 (E, F) and mCPA3 (G, H). These representations show the enriched and depleted residues present at the different identified MCP substrate positions as compared with the reference set. 9729 unique hCPA4 substrate peptides were identified, 4467 for hCPA1, 4207 for hCPA2, and 9680 for mCPA3. In all representations the substrate residues are depicted according to Schechter & Berger nomenclature (36). The frequency of the amino acid occurrence at each position in the sequence set was compared with the occurrence in the peptide library reference set. This comparison corrects for the bias introduced by the amino acid composition of the peptide library. Only statistically significant residues with a p value ≤ 0.01 are plotted in the iceLogo or colored in the heat map. Amino acids height (iceLogo) or color (heat map) shows the degree of difference in the frequency of an amino acid in the experimental set as compared with the frequency in the reference set. In the iceLogo, residues that are statistically over- or underrepresented in the experimental set are respectively shown in the upper or lower part of the iceLogo. Residues colored in pink never occurred at a given position.

Fig. 3.

Amino acid occurrence at P1′ of the identified carboxypeptidase substrates identified using chymotryptic proteome-derived peptide libraries. Percentage of amino acid occurrence at the C terminus of the identified hCPA1 (light gray), hCPA2 (thin downward diagonal lines), mCPA3 (dark gray) and hCPA4 (wide upward diagonal lines) oligopeptide substrates using chymotryptic peptide libraries are plotted and compared with the occurrence at that position for the reference chymotryptic peptide library (black).

This data is in good agreement with previous analyses using synthetic substrates, positional proteomics and peptidomics (8, 23), and thus validates our approach. However, a major difference is the nearly complete absence of Met at the P1′ position, which was previously considered to serve as a good P1′ substrate residue for this enzyme. Considering that Met oxidation might alter its cleavage susceptibility, additionally a slightly modified assay was performed. Here, the methionine oxidation step preceding the primary HPLC run was omitted and as a result, the frequency of Met-ending peptides cleaved by hCPA4 increased 36-fold, from 0.11% to 4.11% at P1′ in the oligopeptide substrates (supplemental Fig. S3).

The Substrate Specificity Profile of the Human Carboxypeptidases A1 (hCPA1) and A2 (hCPA2)

We further validated our approach by assessing the specificity profiles of two previously characterized MCPs. A chymotryptic peptide library was used to assay hCPA1, yielding 4467 18O-labeled peptides (84% of all identified peptides), and hCPA2, yielding 4207 18O-labeled peptides (92% of all identified peptides). The hence derived specificity profiles are shown in Figs. 2C and 2D for hCPA1 and Figs. 2E and 2F for hCPA2. The amino acid occurrences used to build these profiles are further shown in Fig. 3 for the P1′ position and in supplemental Fig. S2 for the P1 position. The P1′ substrate preferences of hCPA1 are similar to those of hCPA4, though a decreased preference for basic amino acids at P1 is observed for hCPA1. Our data further confirm the previously described strong preference of hCPA2 for aromatic residues at the C-terminal position. Lys, Arg, Gln and Leu show an increased frequency of occurrence at P1 for hCPA2 as compared with the reference set. An inhibitory effect of Pro and a decreased occurrence of Thr and Gly when compared with the reference set at P1 can also be observed for hCPA2.

Substrate Specificity Characterization of Mast Cell Carboxypeptidase

Mast cell carboxypeptidase, or CPA3, is found in mast cell granules. Recent reports suggested a role for CPA3 in regulating innate immune responses and mast cell granule homeostasis (37). Although CPA3 is known for many years, its functional properties remain poorly characterized. The difficulty to obtain large amounts of purified CPA3 from natural sources, its instability and the failures in establishing recombinant production of this MCP help to explain the lack of functional CPA3 studies. Previously, CPA3 was shown to hydrolyze the typical substrates of pancreatic CPA and peptides carrying a C-terminal hydrophobic residue, indicative of A-like MCP activity. Taking advantage of the fact that our approach requires only small amounts of CP for substrate specificity characterization, we used the chymotryptic library to assay purified mCPA3 from mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells to characterize its substrate preferences (mouse and human CPA3 display 81.3% identity and 94.2% similarity). LC-MS/MS analysis of the COFRADIC-isolated peptides identified 9680 mCPA3 cleaved peptides (85% of all identified peptides). The substrate preferences of mCPA3 reveal a typical MCP specificity profile, as P1′ mainly determines substrate selection additionally influenced by the amino acid at P1 (Figs. 2G and 2H). Interestingly, preferred substrates of mCPA3 contained large aromatic amino acids at their C termini (Phe, Tyr, or Trp), similar to hCPA2 (Fig. 3). Hydrophobic amino acids (Leu and Ile), are the main representatives at the penultimate position in the oligopeptide substrates identified, whereas Thr, Gly, Pro and acidic amino acids are again poorly represented (supplemental Fig. S2).

Carboxypeptidase Substrate Specificity Profiling Using Proteome-derived Lys-N Peptide Libraries

Protease-derived peptide libraries generated with endoproteases are composed of peptides with a characteristic amino acid preference at one of the peptide termini. Chymotrypsin cleavage generates a vast number of potential substrates for A-like MCPs, hence possibly introducing a substrate bias. Therefore, we evaluated a peptide library created using the metalloendopeptidase Lys-N. This protease selectively cleaves the peptide bond N-terminal of Lys, and as a result it generates a C-terminal unbiased peptide library (i.e. C termini of Lys-N generated peptides do not display any amino acid preference (supplemental Fig. S4)) (38, 39). This library typically contains longer peptides and thus on average more hydrophobic peptides that elute over a larger interval as compared with chymotryptic peptides. As a consequence, in the first RP-HPLC separation primary fractions were collected in a broader time-interval when compared with the chymotryptic library. The substrate specificities of hCPA1, hCPA2, mCPA3 and hCPA4 were then profiled using these peptide libraries. 3275 unique substrates for hCPA1 were identified (46% of all identified peptides), 2064 unique peptides for hCPA2 (36%), 2440 unique substrates for mCPA3 (51%), and 3503 unique peptides for hCPA4 (52%).

The derived substrate preferences were further visualized as iceLogos (Fig. 4A) and heat maps (supplemental Fig. S5). In addition, the amino acid occurrences used to build these profiles are shown in Fig. 4B for the P1′ position and in supplemental Fig. S6 for P1. Of note here is that, in contrast to the chymotryptic peptide library, and given the unbiased nature of the Lys-N generated peptide C termini, the iceLogos show an overall higher contribution of P1′ to the substrate specificity profile. Correspondingly, P1 is shown to contribute moderately to the MCP specificity.

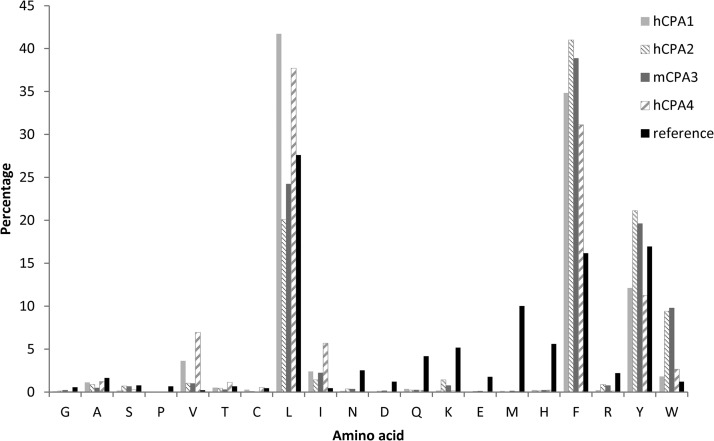

Fig. 4.

Lys-N proteome-derived peptide library assay. A, IceLogo representations of the substrate preferences for hCPA1 (upper left), hCPA2 (upper right), mCPA3 (lower left) and hCPA4 (lower right) derived from Lys-N peptide libraries. These representations show the enriched and depleted residues present at the different identified MCP substrate positions as compared with the Lys-N peptide library reference set. 3275 hCPA1 substrate peptides were identified, 2064 for hCPA2, 2440 for mCPA3 and 3503 for hCPA4. In all representations, the substrate residues are depicted according to the Schechter & Berger nomenclature (36). The frequency of the amino acid occurrence at each position in the sequence set was compared with the occurrence in the peptide library reference set. Only statistically significant residues with a p value < 0.01 are plotted in the iceLogo. Amino acids height show the degree of difference in the frequency of an amino acid in the experimental set as compared with the frequency in the reference set. In the iceLogo, residues that are statistically over- or underrepresented in the experimental set are respectively shown in the upper or lower part of the iceLogo. B, Amino acid occurrences at the P1′ position for the substrates of hCPA1 (light gray), hCPA2 (thin downward diagonal lines), mCPA3 (dark gray) and hCPA4 (wide upward diagonal lines) using Lys-N peptide libraries are plotted and compared with the occurrence at that position for the reference Lys-N peptide library (black).

A general analysis of the displayed specificity profiles reveals strong similarities with those derived using the chymotryptic library, in which hCPA2 and mCPA3 are more efficient in removing large hydrophobic amino acids like Trp or Tyr, when compared with hCPA1 and hCPA4 (Fig. 4B). For the Lys-N library, no methionine oxidation step was performed, enabling for a better evaluation of the occurrence of Met in the overall substrate specificity profiles. As a consequence, Met appears even among the preferred P1′ residues (supplemental Fig. S5).

As mentioned above, the Lys-N library offers the possibility to incorporate in the analysis those substrates from which the CP has released two (or more) amino acids. To assess the occurrence of two sequential cleavages, 18O-labeled peptides matching the following pattern: KX1X2…X(n-1)Xn↓x1x2K (where KX1X2…X(n-1)Xn is the 18O-labeled identified peptide product and x1x2K the bioinformatically deduced primed side sequence) were considered. The presence of a Lys at P3′ position suggests that both KX1X2…X(n-1)Xnx1, and KX1X2…X(n-1)Xnx1x2 can be considered as CP substrates. The hCPA1 specificity profile presented in Fig. 4A only considered KX1X2…X(n-1)Xnx1 as substrates, but we can now also incorporate the 646 hCPA1 peptide substrates matching the KX1X2…X(n-1)Xnx1x2 pattern (i.e. 16% of the total substrate peptides considered). As a result, we obtain a more stringent substrate specificity profile (supplemental Fig. S7A), including information on double hCPA1 cleavages. More specifically, a higher frequency of hydrophobic amino acids like Phe, Leu or Val at P1 can be observed when compared with the original profile (Fig. 4A). For example, the frequency of Leu at P1 went from 10.8% to 14.2% when double cleavages were considered. Similarly, we introduced the information of two sequential cleavages in the iceLogos of hCPA2, mCPA3, and hCPA4 (supplemental Figs. S7B, S7C, and S7D).

Alternatively, we can reduce the occurrence of sequential cleavages by making use of shorter protease incubation times. When hCPA1 was incubated with the Lys-N peptide library for a short time, the number of peptides double processed by the CP diminished to ∼5%, whereas the resulting specificity profile shows again the increased preference of hydrophobic amino acids at P1 position (supplemental Figs. S7E and S7F). Interestingly, differences in P1′ specificity are also observed, when compared with the standard long incubation experiment (Fig. 4A). At short times, Tyr, Phe and Leu are relatively favored at this position, most likely reflecting a kinetic preference for these amino acids (supplemental Fig. S7F).

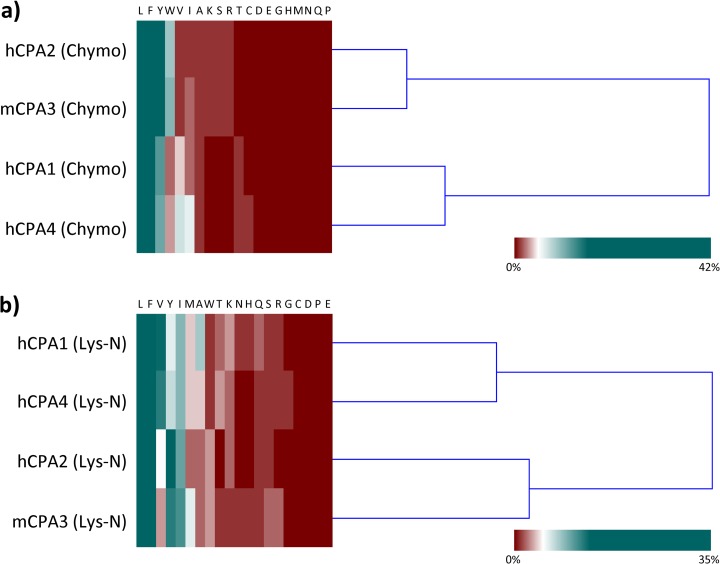

Classification of A-like Metallocarboxypeptidases According to Their Substrate Specificity Profiles

In mammals there are six genes of A-like M14 metallocarboxypeptidases (CPA1 to CPA6) and all of them hydrolyze C-terminal hydrophobic amino acids (8, 21, 40, 41). Given that CPA1 and CPA2 were the first characterized members showing characteristic specificities, A-like enzymes were further classified in A1-like forms (that prefer both small aliphatic as well as bulky aromatic amino acids) and A2-like forms (showing a strong preference for large aromatic residues). Figs. 3 and 4B show the frequencies of the amino acid occurrence at P1′ for each of the MCPs here assayed (CPA1 to 4) and allow for a direct comparison of their substrate preferences. The substrate specificities of these enzymes can similarly be compared by plotting differential iceLogos (supplemental Fig. S8). These comparisons reveal hCPA4 as an A1-like and mCPA3 as an A2-like enzyme according to the established classification. Further, hierarchical cluster analysis of the P1′ substrate specificity profile of the MCPs analyzed using chymotryptic or Lys-N proteome-derived peptide libraries revealed that for both types of libraries, hCPA1 groups close to hCPA4 in terms of its P1′ substrate specificity, whereas hCPA2 and mCPA3 cluster separately (Fig. 5), and thus enables to cluster enzymes according to their differences in the observed substrate preferences.

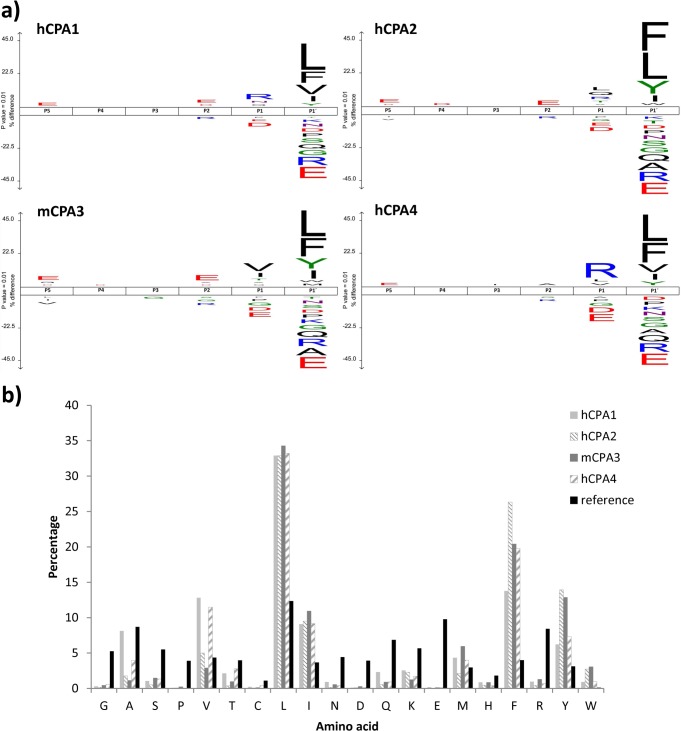

Fig. 5.

Cluster analysis of the P1′ substrate specificity profile of the MCPs analyzed using chymotryptic or Lys-N proteome-derived peptide libraries. A, Cluster analysis of the P1′ substrate specificity data of hCPA1, hCPA2, mCPA3 and hCPA4 using chymotryptic proteome-derived peptide libraries. B, Cluster analysis of the P1′ substrate specificity data of hCPA1, hCPA2, mCPA3 and hCPA4 using Lys-N proteome-derived peptide libraries. Each dendrogram represents the hierarchical Euclidian distance structure between the substrate specificity profiles that was computed using hierarchical clustering with the complete linkage algorithm and indicates the degree of similarity in the P1′ substrate specificity profiles of the four MCPs analyzed. For both types of libraries, hCPA1 groups close to hCPA4 in terms of its P1′ substrate specificity, whereas hCPA2 and mCPA3 cluster separately.

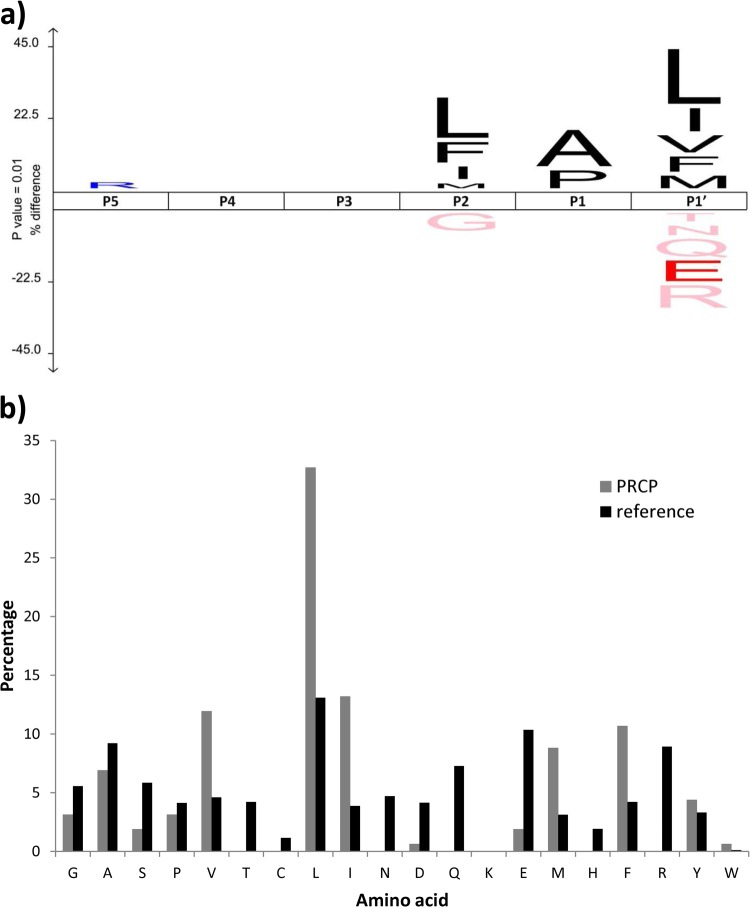

Substrate Preferences for Prolylcarboxypeptidase

Finally, to demonstrate the more universally applicability of our method, we profiled the substrate specificity of prolylcarboxypeptidase (lysosomal Pro-Xaa carboxypeptidase or PRCP), a SCP that plays a key role in energy homeostasis and therefore represents a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of obesity (42). This enzyme is also known as a regulator of cardiovascular functions, with a cardioprotective role against thrombosis and hypertension (43). We here made use of the Lys-N peptide library to evaluate the specificity of recombinant human PRCP and focused our analysis on primary cleavage events by solely taking into account 18O-labeled peptides displaying the KX1X2…X3X4X5↓x1K pattern. The PRCP substrate specificity profile (Fig. 6A), generated using 159 unique identified 18O-labeled peptides, shows a preference of Pro and Ala at P1, in line with the substrate profile obtained using MSP-MS (20), where PRCP was found to cleave single amino acids from the C terminus when proline or alanine occupied P1. As described previously, hydrophobic amino acids (e.g. Leu, Ile, Phe, Val, Met) appear among the preferred residues at P1′ (20, 44, 45), whereas additionally nonhydrophobic amino acids like Ser, Pro, Glu, or Asp can also be tolerated at this position (Fig. 6B). Indeed, an analysis of nonshifted fractions for this experiment shows the presence of 18O-labeled substrates carrying a C-terminal Ser, Pro, or Glu (i.e. 5% of all identified 18O-labeled peptides included in the profile presented in Fig. 6). By contrast, PRCP does not accept Arg, His, Gln, Asn, or Thr in this position. Interestingly, our method has shown to be capable of capturing the extended substrate specificity profile of PRCP, because a clear influence of P2 in substrate selection could be observed; a PRCP feature unnoticed so far. Although hydrophobic residues at P2 favor substrate cleavage, Gly seems to have an adverse effect. The importance of the P2 position might be the result of certain conserved structural features among S28 proteases that besides PRCP includes a dipeptidyl peptidase (DDP7), for which the residue N-terminal to the cleaved Pro/Ala was shown to be of importance for substrate recognition (46).

Fig. 6.

Substrate specificity profile of PRCP using a Lys-N proteome-derived peptide library. A, IceLogo representation of 159 unique substrate peptide sequences for PRCP (i.e. 18O-labeled peptides displaying the KX1X2…X3X4X5↓xaK pattern). These representations show the enriched and depleted residues present at the different identified PRCP substrate positions as compared with the Lys-N peptide library reference set. In all representations, the substrate residues are depicted according to the Schechter & Berger nomenclature (36). The frequency of the amino acid occurrence at each position in the sequence set was compared with the occurrence in the peptide library reference set. Only statistically significant residues with a p value < 0.01 are plotted in the iceLogo or colored in the heat map. Amino acids height show the degree of difference in the frequency of an amino acid in the experimental set as compared with the frequency in the reference set. Residues that are statistically over- or underrepresented in the experimental set are respectively shown in the upper or lower part of the iceLogo. B, Amino acid occurrences at the P1′ position for the PCRP substrates (gray) are compared with the occurrence at that position for the reference Lys-N peptide library (black).

DISCUSSION

Carboxypeptidases participate in C-terminal peptide and protein processing and are thereby implicated in the regulation of a great variety of biological processes including blood coagulation/fibrinolysis (47), blood pressure regulation (6, 7), pro-hormone and neuropeptide processing (8, 48–50), and are also implicated in various pathological conditions such as cancer (51). Despite the importance of these processes, the lack of tools enabling the study of C-terminal processing has hampered identification of CP substrates. The inherently low chemical reactivity of the carboxylic acid group and the difficulty to discriminate peptide/protein C-terminal carboxyl functions from carboxyl functions of the acidic amino acid side chains have long been important obstacles for developing specific methodologies for enriching C termini (52, 53). In addition, C-terminal sequencing has generally been less accessible and reliable than N-terminal sequencing, hampering the study of C-terminal proteolysis (53–55). Finally, C-terminal modifications usually affect the ability of CPs to recognize and cleave these peptides, thereby limiting the strategies for the design of probes.

In the present study we took advantage of the altered chromatographic behavior of intact peptides as compared with their proteolytic fragments to develop a sensitive and comprehensive method to profile carboxypeptidase substrate specificities in vitro. We present a proteome-derived peptide library approach that allows for the MS-based identification of CP cleavage products, concomitantly allowing for cleavage site identification (both primed and nonprimed side specificities). Further, 18O-labeling of neo-C termini permits to discriminate CP products from copurifying peptides and we showed that up to a 90% of all COFRADIC-sorted and identified peptides report CP activity. Additionally, our approach can provide information about subsite cooperativity, although no such cooperativity was observed for the here analyzed CPs (data not shown). Our approach was optimized using CPs of the M14 family that show a strong preference for hydrophobic amino acids and as a result mainly hydrophilic shifts were observed on C-terminal amino acid release (inset in Fig. 1B). We evaluated different members of the A-like subclass of MCPs and presented results that agree with previous data obtained using synthetic substrates, positional proteomics and peptidomics (8, 23). All of this suggests that our technique is of general use for assaying CPs that prefer hydrophobic amino acids (A-like in MCPs or C-type in SCPs). Further, we profiled the serine carboxypeptidase PRCP, which showed a substrate specificity profile not restricted to the removal of hydrophobic amino acids and matching and extending previously published observations. However, some PRCP substrates with Ser, Pro, or Glu at their C terminus were identified in the nonshifted fractions. Given that these fractions are very crowded, this may hamper 18O-labeled peptide identification because of peptide ionization suppression, and thus most likely our approach underestimates the occurrence of these particular amino acids at P1′. Further optimization might be required to apply this approach to CPs with other type of substrate preferences (e.g. for basic or acidic amino acids). In addition, our approach might enable assaying the specificities of other C-terminal exopeptidases such as peptidyl dipeptidases, which include the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE).

When our approach is compared with other peptide-centric approaches to study CP substrate preferences, such as MSP-MS or peptidomics (8, 20–22), we observe that one of the advantages of our proteome-derived approach is the ability to identify much larger numbers of substrates, which ensures a statistical more sound analysis of specificity profiles. As an example, a peptidomic analysis of hCPA4 (8) identified 44 oligopeptide substrates, as compared with the 9729 and 3503 peptide substrates identified in our study using respectively a chymotryptic and a Lys-N peptide library. This is partially explained by the fact that proteome-derived libraries offer a much greater number of possible substrates with broader sequence diversities. In addition, and as shown for PRCP, our method enables the evaluation of extended substrate specificity profiles and thus the importance of the different CP subsites in substrate selection. When making use of shorter protease incubation times and in analogy with the previous reported quantitative approaches (e.g. MSP-MS), efficient substrates can be distinguished from less efficient ones. Further, alternative strategies to assess the efficiency of CP cleavage could be integrated when making use of proteome-derived peptide libraries (56).

The main focus of this study was on A-like MCPs that display overlapping but clearly distinctive substrate specificities. It was proposed that evolutionary traits allowed CPA1 and CPA2 to diverge from one another with respect to their substrate selectivity (57). hCPA2 displays a stronger preference for bulkier hydrophobic amino acids in comparison to hCPA1, which is able to more efficiently cleave small aliphatic residues (8). This in contrast with bovine CPA, which is the only pancreatic CPA gene in Bos taurus and displays a broad substrate specificity. Our analysis confirms the characteristic preference of hCPA2 for large hydrophobic amino acids like Phe, Tyr, or Trp. As for hCPA1, it confirms its less restricted specificity profile, because this enzyme performs better against amino acids like Leu, Val, or Ala. Profiling the optimal peptide substrates of hCPA4 identified in this study, demonstrates that this enzyme is essentially an A1-like enzyme, as suggested previously (8). The performance of the chymotryptic library seems to be better when describing the P1′ substrate specificity of MCPs. The chymotryptic library-derived specificity profile for hCPA2 displays a more restricted preference for large aromatic hydrophobic amino acids at P1′, in analogy with previously published kinetic data (8). The Lys-N library seemingly is not able to discriminate between the differences in affinity for Leu or Ile that exist between hCPA1 and hCPA2 (Fig. 4B). It is important to note that the use of chymotrypsin or Lys-N generates libraries with different peptide composition and length. In the former and although up to 3 missed cleavages could be observed, there is a lower content of internal hydrophobic residues, whereas the latter lack internal Lys residues and thus the presence of this amino acid cannot be profiled. Some of these particularities might explain why both libraries perform differently when assessing certain aspects of MCP substrate preferences. The use of two different peptide libraries should minimize the bias introduced by each of them, and as a result, generates a better overall profile of enzyme preferences.

All the analyzed MCPs display overlapping specificity profiles at the P1 position, although some subtle differences can be observed (Figs. 2 and 4, and supplemental Figs. S2, S5, and S6). It is striking to note the generally strong negative effect of a P1 Pro on substrate selection. Another common feature at P1 is the presence of Gly as a disfavored amino acid, although this effect it is less pronounced for hCPA1. This negative effect of Pro and Gly in the penultimate position seems to be a general feature for MCPs as it has also been observed for CPM (58), CPB (58), CPU/TAFI (59), CPN (59), CPE (60), CPD (61), and CPA6 (21). Through molecular modeling and docking studies of CPM with different substrates, Deiteren et al. (58) suggest that a Gly at the P1 position permits an excessive flexibility of the substrate, explaining the unfavorable catalytic parameters for such substrates. In addition, the here studied enzymes in general disfavor acidic amino acids at P1, an observation which is more pronounced for hCPA4. Conversely, basic amino acids are favored for most of them, although again this effect is clearer for hCPA4, being most probably the most discriminating carboxypeptidase in the case of acid or basic P1 residues. In all cases, hydrophobic amino acids are among the preferred amino acids at P1 and their occurrence is even underestimated at this position, viewing the fact that hydrophobic amino acids at the P1 position favor the CP-mediated release of a second C-terminal amino acid, and as a result only the products of the ultimate cleavage are evaluated. Shorter incubation times or the use of the Lys-N library to determine sequentially cleaved substrates can partially overcome the bias introduced by sequential cleavages (supplemental Fig. S7). In this context, the Lys-N library additionally provided information about the occurrence of sequential cleavages for these proteases, a phenomenon difficult to address otherwise.

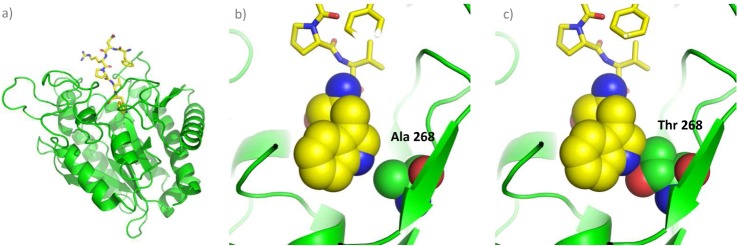

One of the advantages of our approach is that it allows, in a single experiment and using small quantities of a carboxypeptidase, a complete elucidation of CP cleavage site preferences. For instance, using very limited amounts of enzyme we here characterized the substrate specificity of mast cell carboxypeptidase (MC-CPA or CPA3), an enzyme that was discovered 25 years ago (62) but for which no in-depth analysis of its enzymatic properties was available. CPA3 was found to be implicated in the protection against certain snake venom toxins in mice, and as a result this enzyme would play a role in regulating innate immune responses (63, 64). Recently, a mouse strain lacking CPA3 expression (MC-CPA−/− strain) showed altered mast cell staining, compatible with an immature phenotype, and displayed a strongly impaired storage of one of the MC chymases -mouse mast cell proteinase-5 (mMCP-5)- in the granules, indicating that CPA3 may participate in regulating secretory granule homeostasis (65). Although, in vitro assays using synthetic CP substrates and some bioactive peptides have previously provided some insights into the cleavage properties and potential physiological substrates of this mast cell CP, we here generated a comprehensive peptide substrate specificity profile of mCPA3 (Figs. 2 and 4). Mast cell CP was found to represent an A2-like MCP, with a marked preference for large hydrophobic amino acids like Trp, Tyr and Phe. This contradicts predictions based on structural models suggesting a preference of CPA3 for intermediate sized hydrophobic residues (21). A hierarchical cluster analysis, further confirms this classification, because it groups mCPA3 close to hCPA2 in terms of substrate specificity, whereas hCPA1 and hCPA4 cluster separately (Fig. 5). Although clearly being an A2-like MCP, it shows a relative higher preference for amino acids like Leu, Ile or Met, and a lower affinity for Phe in P1′ when compared with hCPA2 (Figs. 3 and 4b). Despite the prediction that Ser 253 of mCPA3 (using the numbering system of bovine CPA) would interfere with the binding of very large amino acids like Trp (21), the here obtained specificity profile suggests that this position would not be critical in substrate specificity determination. As previously suggested (8, 66–68), the amino acid in position 268 would be the key determinant of an A1-like or an A2-like specificity. In the case of mast cell carboxypeptidase, the presence of an Ala in position 268 (Ala-376 in mCPA3), in contrast to the Thr present in hCPA1 and hCPA4, might explain the specificity for bulkier amino acids like Tyr, Trp or Phe (Suppl. Table S1). We built a 3D model of mCPA3 accommodating a hexapeptide in its active site (Fig. 7A), which shows that the amino acid at position 268 restricts the size of the S1′ binding pocket. Figs. 7B and 7C illustrate how the replacement of an Ala for a Thr at this position decreases the pocket dimensions and limits the ability of the enzyme to accommodate bulky C-terminal amino acids.

Fig. 7.

Structural based model of mouse CPA3 in complex with a hexapeptide. A, Cartoon representation of mCPA3 (shown in green) in complex with a Trp-ending hexapeptide (shown as a yellow stick model). B, Close-up view of the S1′ specificity pocket. The hexapeptide is shown as a yellow stick model, with the exception of the C-terminal Trp of which the atoms (except of hydrogens) are shown as spheres. The Ala in position 268 is also indicated and shown as spheres. C, Detailed view of the S1′ pocket of mCPA3 in which the Ala in position 268 has been mutated to Thr (Ala268>Thr). The atom color coding is as follows: green for C (enzyme), yellow for C (peptide), cyan for N, and red for O.

The description of mast cell carboxypeptidase as an A2-like MCP has implications on the products that this enzyme generates on digestion of angiotensin I (Ang-I), one of the putative physiological substrates of CPA3. Recently, Pereira et al. (69) compared the action of rat CPA1 and CPA2 on Ang-I. Although an A2-like enzyme mainly produces Ang-(1–9) on Ang-I digestion, an A1-like enzyme is more efficient in further processing Ang-(1–9) into Ang-(1–7) (69). This observation can be explained based on the more restricted substrate specificity displayed by A2-like enzymes. Knowledge of the optimal cleavage sequences for mast cell carboxypeptidase will be very useful to corroborate in vivo cleavage events and might enable prediction of novel biological mast cell carboxypeptidase substrates, which are key to gain insight into the biological function of this enzyme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Gunnar Pejler for the generous gift of mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells.

Footnotes

* K.G. and L.M. acknowledge support of the Ghent University Multidisciplinary Research Partnership “Bioinformatics: from nucleotides to networks.” K.G. and S.D. have been supported by the PRIME-XS project, grant agreement number 262067, funded by the European Union 7th Framework Program. F.X.A. acknowledges support of the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion (MICINN) of Spain (project BIO2010-22321-C02), and the European Commission (project Strep FP7-Health-2009–241919-LIVIMODE). P.V.D. is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S8 and Table S1.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S8 and Table S1.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- ACE

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ACE2

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- Ang-I

- Angiotensin I

- BMMCs

- Bone marrow-derived mast cells

- COFRADIC

- COmbined FRActional DIagonal Chromatography

- CPs

- Carboxypeptidases

- CPAs

- A-like carboxypeptidases

- hCPA1

- Human carboxypeptidase A1

- hCPA2

- Human carboxypeptidase A2

- mCPA3

- Mouse carboxypeptidase A3

- hCPA4

- Human carboxypeptidase A4

- MC-CPA

- Mast cell carboxypeptidase

- MCPs

- Metallocarboxypeptidases

- mMCP-5

- Mouse mast cell proteinase-5

- MSP-MS

- Multiplex substrate profiling by mass spectrometry

- PRCP

- Prolylcarboxypeptidase

- SCPs

- Serine carboxypeptidases.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vendrell J., Avilés F. X. (1999) Carboxypeptidases. In: Turk V., ed. Proteases: new perspectives, pp. 13–34, Birkhauser, Basel [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arolas J. L., Vendrell J., Aviles F. X., Fricker L. D. (2007) Metallocarboxypeptidases: emerging drug targets in biomedicine. Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 349–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lyons P. J., Fricker L. D. (2011) Carboxypeptidase O is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored intestinal peptidase with acidic amino acid specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39023–39032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mortensen U. H., Olesen K., Breddam K. (1999) Carboxypeptidase C including carboxypeptidase Y. In: Barrett A. J., Rawlings N. D., Woessner J. F., eds. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes, pp. 389–393, Academic Press, London [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodriguez de la Vega M., Sevilla R. G., Hermoso A., Lorenzo J., Tanco S., Diez A., Fricker L. D., Bautista J. M., Avilés F. X. (2007) Nna1-like proteins are active metallocarboxypeptidases of a new and diverse M14 subfamily. FASEB J. 21, 851–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuba K., Imai Y., Ohto-Nakanishi T., Penninger J. M. (2010) Trilogy of ACE2: a peptidase in the renin-angiotensin system, a SARS receptor, and a partner for amino acid transporters. Pharmacol. Ther. 128, 119–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pshezhetsky A. V., Hinek A. (2009) Serine carboxypeptidases in regulation of vasoconstriction and elastogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 19, 11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tanco S., Zhang X., Morano C., Avilés F. X., Lorenzo J., Fricker L. D. (2010) Characterization of the substrate specificity of human carboxypeptidase A4 and implications for a role in extracellular peptide processing. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18385–18396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Son Y. J., Kim C. K., Kim Y. B., Kweon D. H., Park Y. C., Seo J. H. (2009) Effects of citraconylation on enzymatic modification of human proinsulin using trypsin and carboxypeptidase B. Biotechnol. Prog. 25, 1064–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bergman T., Cederlund E., Jornvall H., Fowler E. (2003) C-terminal sequence analysis. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 11, Unit 11.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raksakulthai R., Haard N. F. (2001) Purification and characterization of a carboxypeptidase from squid hepatopancreas (Illex illecebrosus). J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 5019–5030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arai S., Noguchi M., Kurosawa S., Kato H., Fujimaki M. (1970) APPLYING PROTEOLYTIC ENZYMES ON SOYBEAN. 6. Deodorization Effect of Aspergillopeptidase A and Debittering Effect of Aspergillus Acid Carboxypeptidase. J. Food Sci. 35, 392–395 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Umetsu H., Matsuoka H., Ichishima E. (1983) Debittering mechanism of bitter peptides from milk casein by wheat carboxypeptidase. J. Agricultural Food Chem. 31, 50–53 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barrios A. M., Craik C. S. (2002) Scanning the prime-site substrate specificity of proteolytic enzymes: a novel assay based on ligand-enhanced lanthanide ion fluorescence. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 12, 3619–3623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gosalia D. N., Salisbury C. M., Ellman J. A., Diamond S. L. (2005) High throughput substrate specificity profiling of serine and cysteine proteases using solution-phase fluorogenic peptide microarrays. Mol. Cell Proteomics 4, 626–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diamond S. L. (2007) Methods for mapping protease specificity. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11, 46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. auf dem Keller U., Schilling O. (2010) Proteomic techniques and activity-based probes for the system-wide study of proteolysis. Biochimie 92, 1705–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schilling O., Overall C. M. (2008) Proteome-derived, database-searchable peptide libraries for identifying protease cleavage sites. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 685–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van den Berg B. H., Tholey A. (2012) Mass spectrometry-based proteomics strategies for protease cleavage site identification. Proteomics 12, 516–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Donoghue A. J., Eroy-Reveles A. A., Knudsen G. M., Ingram J., Zhou M., Statnekov J. B., Greninger A. L., Hostetter D. R., Qu G., Maltby D. A., Anderson M. O., Derisi J. L., McKerrow J. H., Burlingame A. L., Craik C. S. (2012) Global identification of peptidase specificity by multiplex substrate profiling. Nat. Methods 9, 1095–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyons P. J., Fricker L. D. (2010) Substrate specificity of human carboxypeptidase A6. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38234–38242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lyons P. J., Fricker L. D. (2011) Peptidomic approaches to study proteolytic activity. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 18, Unit18.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van Damme P., Staes A., Bronsoms S., Helsens K., Colaert N., Timmerman E., Aviles F. X., Vandekerckhove J., Gevaert K. (2010) Complementary positional proteomics for screening substrates of endo- and exoproteases. Nat. Methods 7, 512–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schilling O., Barré O., Huesgen P. F., Overall C. M. (2010) Proteome-wide analysis of protein carboxy termini: C terminomics. Nat. Methods 7, 508–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gevaert K., Impens F., Van Damme P., Ghesquière B., Hanoulle X., Vandekerckhove J. (2007) Applications of diagonal chromatography for proteome-wide characterization of protein modifications and activity-based analyses. FEBS J. 274, 6277–6289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pallares I., Bonet R., Garcia-Castellanos R., Ventura S., Aviles F. X., Vendrell J., Gomis-Ruth F. X. (2005) Structure of human carboxypeptidase A4 with its endogenous protein inhibitor, latexin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3978–3983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pallares I., Fernandez D., Comellas-Bigler M., Fernandez-Recio J., Ventura S., Aviles F. X., Bode W., Vendrell J. (2008) Direct interaction between a human digestive protease and the mucoadhesive poly(acrylic acid). Acta Crystallogr. D 64, 784–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reverter D., Garcia-Saez I., Catasus L., Vendrell J., Coll M., Avilés F. X. (1997) Characterisation and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of human pancreatic procarboxypeptidase A2. FEBS Lett. 420, 7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Staes A., Impens F., Van Damme P., Ruttens B., Goethals M., Demol H., Timmerman E., Vandekerckhove J., Gevaert K. (2011) Selecting protein N-terminal peptides by combined fractional diagonal chromatography. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1130–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kall L., Storey J. D., MacCoss M. J., Noble W. S. (2008) Assigning significance to peptides identified by tandem mass spectrometry using decoy databases. J. Proteome Res. 7, 29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martens L., Hermjakob H., Jones P., Adamski M., Taylor C., States D., Gevaert K., Vandekerckhove J., Apweiler R. (2005) PRIDE: the proteomics identifications database. Proteomics 5, 3537–3545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Colaert N., Helsens K., Martens L., Vandekerckhove J., Gevaert K. (2009) Improved visualization of protein consensus sequences by iceLogo. Nat. Methods 6, 786–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roy A., Kucukural A., Zhang Y. (2010) I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc. 5, 725–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang Y. (2007) Template-based modeling and free modeling by I-TASSER in CASP7. Proteins 69, 108–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bayés A., Fernández D., Solà M., Marrero A., Garcia-Piqué S., Avilés F. X., Vendrell J., Gomis-Ruth F. X. (2007) Caught after the Act: a human A-type metallocarboxypeptidase in a product complex with a cleaved hexapeptide. Biochemistry 46, 6921–6930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schechter I., Berger A. (1967) On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 27, 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pejler G., Knight S. D., Henningsson F., Wernersson S. (2009) Novel insights into the biological function of mast cell carboxypeptidase A. Trends Immunol. 30, 401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hohmann L., Sherwood C., Eastham A., Peterson A., Eng J. K., Eddes J. S., Shteynberg D., Martin D. B. (2009) Proteomic analyses using Grifola frondosa metalloendoprotease Lys-N. J. Proteome Res. 8, 1415–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raijmakers R., Neerincx P., Mohammed S., Heck A. J. (2010) Cleavage specificities of the brother and sister proteases Lys-C and Lys-N. Chem. Commun. 46, 8827–8829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wei S., Segura S., Vendrell J., Aviles F. X., Lanoue E., Day R., Feng Y., Fricker L. D. (2002) Identification and characterization of three members of the human metallocarboxypeptidase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14954–14964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goldstein S. M., Kaempfer C. E., Kealey J. T., Wintroub B. U. (1989) Human mast cell carboxypeptidase. Purification and characterization. J. Clin. Invest. 83, 1630–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jeong J. K., Diano S. (2013) Prolyl carboxypeptidase and its inhibitors in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 24, 61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chajkowski S. M., Mallela J., Watson D. E., Wang J., McCurdy C. R., Rimoldi J. M., Shariat-Madar Z. (2011) Highly selective hydrolysis of kinins by recombinant prolylcarboxypeptidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 405, 338–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Odya C. E., Marinkovic D. V., Hammon K. J., Stewart T. A., Erdös E. G. (1978) Purification and properties of prolylcarboxypeptidase (angiotensinase C) from human kidney. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 5927–5931 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tan F., Erdös E. G. (2004) Lysosomal Pro-X carboxypeptidase. In: Barrett A. J., Rawlings N. D., Woessner J. F., eds. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes, pp. 1936–1937, Academic Press, London [Google Scholar]

- 46. Soisson S. M., Patel S. B., Abeywickrema P. D., Byrne N. J., Diehl R. E., Hall D. L., Ford R. E., Reid J. C., Rickert K. W., Shipman J. M., Sharma S., Lumb K. J. (2010) Structural definition and substrate specificity of the S28 protease family: the crystal structure of human prolylcarboxypeptidase. BMC Struct. Biol. 10, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Declerck P. J. (2011) Thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor. Hamostaseologie 31, 165- 166, 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cawley N. X., Wetsel W. C., Murthy S. R., Park J. J., Pacak K., Loh Y. P. (2012) New roles of carboxypeptidase E in endocrine and neural function and cancer. Endocr. Rev. 33, 216–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang X., Che F. Y., Berezniuk I., Sonmez K., Toll L., Fricker L. D. (2008) Peptidomics of Cpe(fat/fat) mouse brain regions: implications for neuropeptide processing. J. Neurochem. 107, 1596–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lyons P. J., Callaway M. B., Fricker L. D. (2008) Characterization of carboxypeptidase A6, an extracellular matrix peptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7054–7063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vovchuk I. L., Petrov S. A. (2008) [Role of carboxypeptidases in carcinogenesis]. Biomed. Khim. 54, 167–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Toyo'oka T. (1998) Modern Derivatization Methods for Separation Science, Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nakazawa T., Yamaguchi M., Okamura T. A., Ando E., Nishimura O., Tsunasawa S. (2008) Terminal proteomics: N- and C-terminal analyses for high-fidelity identification of proteins using MS. Proteomics 8, 673–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Samyn B., Hardeman K., Van der Eycken J., Van Beeumen J. (2000) Applicability of the alkylation chemistry for chemical C-terminal protein sequence analysis. Anal. Chem. 72, 1389–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hardeman K., Samyn B., Van der Eycken J., Van Beeumen J. (1998) An improved chemical approach toward the C-terminal sequence analysis of proteins containing all natural amino acids. Protein Sci. 7, 1593–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Impens F., Colaert N., Helsens K., Plasman K., Van Damme P., Vandekerckhove J., Gevaert K. (2010) MS-driven protease substrate degradomics. Proteomics 10, 1284–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gardell S. J., Craik C. S., Clauser E., Goldsmith E. J., Stewart C. B., Graf M., Rutter W. J. (1988) A novel rat carboxypeptidase, CPA2: characterization, molecular cloning, and evolutionary implications on substrate specificity in the carboxypeptidase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 17828–17836 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Deiteren K., Surpateanu G., Gilany K., Willemse J. L., Hendriks D. F., Augustyns K., Laroche Y., Scharpé S., Lambeir A. M. (2007) The role of the S1 binding site of carboxypeptidase M in substrate specificity and turn-over. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774, 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Willemse J. L., Polla M., Olsson T., Hendriks D. F. (2008) Comparative substrate specificity study of carboxypeptidase U (TAFIa) and carboxypeptidase N: development of highly selective CPU substrates as useful tools for assay development. Clin. Chim. Acta 387, 158–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chen H., Jawahar S., Qian Y., Duong Q., Chan G., Parker A., Meyer J. M., Moore K. J., Chayen S., Gross D. J., Glaser B., Permutt M. A., Fricker L. D. (2001) Missense polymorphism in the human carboxypeptidase E gene alters enzymatic activity. Hum. Mutat. 18, 120–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Novikova E. G., Eng F. J., Yan L., Qian Y., Fricker L. D. (1999) Characterization of the enzymatic properties of the first and second domains of metallocarboxypeptidase D. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 28887–28892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Goldstein S. M., Kaempfer C. E., Proud D., Schwartz L. B., Irani A. M., Wintroub B. U. (1987) Detection and partial characterization of a human mast cell carboxypeptidase. J. Immunol. 139, 2724–2729 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Metz M., Piliponsky A. M., Chen C. C., Lammel V., Abrink M., Pejler G., Tsai M., Galli S. J. (2006) Mast cells can enhance resistance to snake and honeybee venoms. Science 313, 526–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rivera J. (2006) Snake bites and bee stings: the mast cell strikes back. Nat. Med. 12, 999–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Feyerabend T. B., Hausser H., Tietz A., Blum C., Hellman L., Straus A. H., Takahashi H. K., Morgan E. S., Dvorak A. M., Fehling H. J., Rodewald H. R. (2005) Loss of histochemical identity in mast cells lacking carboxypeptidase A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6199–6210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Faming Z., Kobe B., Stewart C. B., Rutter W. J., Goldsmith E. J. (1991) Structural evolution of an enzyme specificity. The structure of rat carboxypeptidase A2 at 1.9-A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 24606–24612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Garcia-Sáez I., Reverter D., Vendrell J., Avilés F. X., Coll M. (1997) The three-dimensional structure of human procarboxypeptidase A2. Deciphering the basis of the inhibition, activation and intrinsic activity of the zymogen. EMBO J. 16, 6906–6913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Smith G. K., Banks S., Blumenkopf T. A., Cory M., Humphreys J., Laethem R. M., Miller J., Moxham C. P., Mullin R., Ray P. H., Walton L. M., Wolfe L. A., 3rd (1997) Toward antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy with the T268G mutant of human carboxypeptidase A1 and novel in vivo stable prodrugs of methotrexate. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15804–15816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pereira H. J., Souza L. L., Costa-Neto C. M., Salgado M. C., Oliveira E. B. (2012) Carboxypeptidases A1 and A2 from the perfusate of rat mesenteric arterial bed differentially process angiotensin peptides. Peptides 33, 67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.