Abstract

Rationale: The effect of indoor air pollutants on respiratory morbidity among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in developed countries is uncertain.

Objectives: The first longitudinal study to investigate the independent effects of indoor particulate matter (PM) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations on COPD morbidity in a periurban community.

Methods: Former smokers with COPD were recruited and indoor air was monitored over a 1-week period in the participant’s bedroom and main living area at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. At each visit, participants completed spirometry and questionnaires assessing respiratory symptoms. Exacerbations were assessed by questionnaires administered at clinic visits and monthly telephone calls.

Measurements and Main Results: Participants (n = 84) had moderate or severe COPD with a mean FEV1 of 48.6% predicted. The mean (± SD) indoor PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations were 11.4 ± 13.3 µg/m3 and 10.8 ± 10.6 ppb in the bedroom, and 12.2 ± 12.2 µg/m3 and 12.2 ± 11.8 ppb in the main living area. Increases in PM2.5 concentrations in the main living area were associated with increases in respiratory symptoms, rescue medication use, and risk of severe COPD exacerbations. Increases in NO2 concentrations in the main living area were independently associated with worse dyspnea. Increases in bedroom NO2 concentrations were associated with increases in nocturnal symptoms and risk of severe COPD exacerbations.

Conclusions: Indoor pollutant exposure, including PM2.5 and NO2, was associated with increased respiratory symptoms and risk of COPD exacerbation. Future investigations should include intervention studies that optimize indoor air quality as a novel therapeutic approach to improving COPD health outcomes.

Keywords: indoor air, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, exacerbations

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines identify indoor air pollution resulting from burning wood and other biomass fuels as a major risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); however, exposures under these conditions are significantly higher than in developed country households. Lower-level pollutant exposure in homes may have adverse health effects in susceptible individuals, such as those with COPD; however, these effects remain largely unknown.

What This Study Adds to the Field

The present study addresses a significant gap in the current evidence base by investigating longitudinal health effects of indoor air quality in patients with COPD in a periurban community. Our results show that despite overall relatively low pollutant burden, indoor pollutant exposures, including particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide, were associated with increased respiratory symptoms and increased risk of COPD exacerbations. These results suggest that future studies investigating the effectiveness of environmental interventions aimed at reducing indoor pollutant concentrations in homes of patients with COPD are warranted.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the third leading cause of death in the United States and the fifth leading cause worldwide, is expected to become increasingly prevalent in upcoming decades (1, 2). Most COPD is caused by environmental exposures; in developed countries, this exposure is primarily cigarette smoke. After COPD begins, evidence indicates that it can be worsened by other environmental exposures. For example, outdoor particulate matter (PM) concentrations have been associated with an increase in COPD hospitalizations and mortality (3, 4). Similarly, outdoor nitrogen dioxide (NO2) exposure has been linked to worse COPD morbidity, including higher rates of exacerbations (4–6).

Although substantial evidence shows that outdoor air pollutants impact COPD, there is much less evidence for the impact of indoor air on COPD, especially in developed countries. Although the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines identify indoor air pollution resulting from burning wood and other biomass fuels as a major risk factor for COPD (7), exposures under these conditions are two to three orders of magnitude higher than in developed country households. In the United States, indoor air quality is important because Americans spend most of their time indoors (8), and individuals with COPD spend more time at home than their age-matched counterparts: approximately 82% of their time is spent indoors in their own home (9). It is critical to determine if the impact of indoor air quality on COPD is harmful, because feasible interventions, such as the placement of high-efficiency particulate air cleaners (10), could be used to improve in-home air quality.

To determine whether common indoor air pollutants represent an adverse effect on COPD health, we conducted a longitudinal study investigating the effects of indoor air quality on COPD health, including respiratory symptoms and exacerbations. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (11, 12).

Methods

Participant Recruitment

Former smokers with COPD were recruited from the Baltimore area. Inclusion criteria included (1) age greater than or equal to 40 years; (2) post-bronchodilator FEV1 less than or equal to 80% predicted; (3) FEV1/FVC less than 70%; and (4) more than 10 pack-years smoking, but having quit more than 1 year before enrollment and exhaled carbon monoxide level less than or equal to 6 ppm (13). Exclusion criteria are presented in the online supplement. Participants provided written informed consent and the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutional Review Board approved the protocol.

Clinical Evaluation

Clinic visits occurred at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. Validated questionnaires assessed quality of life (St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ]) (14); dyspnea (Medical Research Council [MRC] dyspnea scale) (15); and respiratory health (modified American Thoracic Society [ATS]-Division of Lung Disease) (16). Presence of cough and sputum was determined by the following questions from the ATS-Division of Lung Disease: “Do you usually have a cough”? and “Do you usually bring up phlegm from your chest” at each visit and was dichotomized to “yes” or “no.” Frequency of wheeze in the last 4 weeks was assessed as “almost every day, several days a week, a few days a month, only with respiratory infections, or not at all.” Nocturnal symptoms defined as coughing or breathing that disturbs sleep was dichotomized to “yes” or “no.” Frequency of rescue medication use (0, 1, 2, 3, or >4 times daily) was assessed by daily diary. Responses were averaged over each 1-week monitoring period. Spirometry, before and after albuterol, was performed according to ATS criteria (17, 18).

Exacerbations were assessed by questionnaires at each clinic visit and by monthly telephone calls. Any exacerbation was defined as worsening respiratory symptoms requiring antibiotics, oral steroids, or an acute care visit. Severe exacerbations were defined as worsening respiratory symptoms leading to an emergency department visit or hospitalization (19).

Air Quality Assessment

A home inspection was conducted by a trained technician. Air sampling was performed for 1 week at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months in the participant’s bedroom and the main living area, identified as an additional room where the participant reported spending the most time. Indoor air sampling for PM2.5 (PM with aerodynamic size ≤ 2.5 μm) and NO2 was conducted as described previously and in the online supplement (20). The limit of detection for PM2.5 was 0.64 μg/m3. NO2 was measured using a passive sampler (Ogawa badge) (21) and the limit of detection was 0.52 ppb. Secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure was assessed by air nicotine at baseline and hair nicotine at all visits (10, 22), with a limit of detection of 0.02 μg/m3 and 0.025 ng/mg, respectively. Any sample with detectable nicotine was considered evidence of SHS exposure.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were analyzed using Spearman correlations, chi-square tests, and t tests, as appropriate. At each time point, the PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations were used as exposure variables in generalized estimating equations models (23) to account for the correlation arising from repeated measures of the outcomes over time, adjusting for age, sex, education, season, and % predicted FEV1. To evaluate the effect of pollutants on respiratory health, continuous outcomes and binary outcomes (i.e., nocturnal symptoms, exacerbations) were analyzed using negative binomial and logistic regression models, respectively, with PM2.5 and NO2 included as continuous predictors. Both PM2.5 and NO2 were included in models simultaneously, and interaction between pollutants was tested. Interactions between pollutants and sex were also tested. Models were run separately to determine effects of exposure from the bedroom and the main living area. Additional analyses were conducted to include air or hair nicotine as confounding variables. To tease apart whether the adverse health effect of pollutant levels was caused by overall high pollutant burden or whether changing levels within a home contributed to morbidity, joint models estimating the combined effect of variability and mean level of exposure were fit by including both exposure metrics into the model simultaneously (see online supplement).

All analyses were performed with StataSE statistical software, version 11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was defined as P less than 0.05.

Results

Participant Characteristics

All participants (n = 84) had moderate or severe COPD with a mean baseline FEV1 % predicted of 48.6% (Table 1). The mean baseline SGRQ total score and MRC score (± SD) were 39.4 (± 18.0) and 2.5 (± 1.1), respectively. At baseline, 26% of participants reported nighttime awakenings caused by COPD; 36% and 43% of participants reported usual cough and phlegm, respectively; and 18% reported wheeze at least several days a week. Thirty-six (43%) participants reported having an exacerbation in the previous year, with a total of 39 moderate and 16 severe exacerbations.

TABLE 1.

BASELINE PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS

| Participant Characteristics | N = 84 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean yr (SD) |

68.9 (7.4) |

| Sex, n (%) male |

49 (58) |

| Race, n (%) |

|

| White |

74 (88) |

| Black/African American |

8 (10) |

| Other |

2 (2) |

| Marital status, n (%) |

|

| Single |

8 (10) |

| Married |

39 (46) |

| Widowed |

21 (25) |

| Separated or divorced |

16 (19) |

| Education, n (%) |

|

| Less than high school |

17 (20) |

| High school |

17 (20) |

| Some college |

27 (32) |

| Bachelor’s degree |

10 (12) |

| At least some graduate school |

13 (15) |

| Smoking history, mean (SD) |

|

| Pack-years |

56.8 (28.7) |

| Years smoked |

36.7 (10.7) |

| Last cigarette (years since) |

13.1 (9.1) |

| Secondhand smoke exposure, n (%) |

|

| Reported smoking in the home |

14 (17) |

| Presence of hair nicotine |

21 (28) |

| Baseline lung function, mean (SD) |

|

| Pre-BD FEV1, L |

1.34 (0.6) |

| Pre-BD FEV1, % predicted |

48.6 (15.9) |

| Pre-BD FEV1/FVC, % |

51 (10.2) |

| Post-BD FEV1, L |

1.46 (0.6) |

| Post-BD FEV1, % predicted |

52.8 (16.7) |

| Post-BD FEV1/FVC, % |

52 (10.3) |

| Baseline health status |

|

| GOLD stage n (%) |

|

| II |

38 (45) |

| III |

35 (42) |

| IV |

11 (13) |

| SGRQ, mean (SD) |

39.4 (18.0) |

| MMRC, mean (SD) |

2.5 (1.1) |

| Nocturnal symptoms, n (%) |

22 (26) |

| Usual cough, n (%) |

30 (36) |

| Usual phlegm, n (%) |

36 (43) |

| Severe exacerbations previous year, n (%) | 16 (19) |

Definition of abbreviations: BD = bronchodilator; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; MMRC = Modified Medical Research Council; SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Participants reported spending 92% of time indoors, of which 80% was in their own home, including an average of 9.3 hours in their bedroom and 7.5 hours in the main living area where the monitors were placed.

Pollutant Concentrations

The mean (± SD) indoor PM2.5 concentrations for the bedroom and main living area were 11.4 (13.3) and 12.2 (12.2) μg/m3, respectively. The median (interquartile range) PM2.5 concentrations were 8.3 (4.9, 14.4) and 8.3 (4.8, 15.1) μg/m3, respectively. The mean (± SD) indoor NO2 concentrations for the bedroom and main living area were 10.8 (10.6) and 12.2 (11.8) ppb, respectively. The median (interquartile range) NO2 concentrations were 6.8 (4.2, 14.5) and 8.0 (5.2, 16.1) ppb, respectively. No statistical differences existed in PM2.5 or NO2 concentrations between baseline, 3-month, or 6-month visits or by season. Indoor pollutant concentrations were higher in row homes. Indoor NO2 concentrations were higher in homes with a gas stove, gas furnace for heating, and homes that were closer to the street and in front of an arterial street. Indoor PM concentrations were higher in homes with detectable air nicotine and lower in homes that had central air conditioning or were rated as being in above-average condition (see Table E1 in the online supplement).

At baseline, 14 participants (17%) reported having a smoker living in their home; however, approximately half of homes had detectable air nicotine in the bedroom (44%) and main living area (54%). Of those with detectable levels, the mean air nicotine concentration was 0.25 (SD 0.44) and 0.26 (SD 0.57) μg/m3 in the bedroom and main living area, respectively. Most participants provided hair samples (92%); of these, 28% and 47% of participants showed evidence of nicotine exposure at baseline or at any of the three visits, respectively.

Association of Indoor Pollutant Concentrations and Respiratory Health

Bivariate analyses

Higher PM2.5 concentrations in the main living area were associated with increased respiratory symptoms. Each 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was associated with worse dyspnea assessed by modified MRC score (β = 0.18; P = 0.01); more wheeze (β = 0.27; P = 0.001); higher risk of having nocturnal symptoms (odds ratio [OR], 1.44; P = 0.02); and an increase in rescue medication use (β = 0.13; P = 0.02). Each 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 also tended to be associated with higher risk of severe exacerbations (OR, 1.38; P = 0.05) and worse quality of life (SGRQ β = 1.63; P = 0.05). PM2.5 concentrations were not associated with cough, phlegm production, or lung function. Bedroom PM2.5 concentrations were not associated with any measured respiratory outcomes.

Increasing NO2 concentrations in both the main living area and the bedroom were associated with worse dyspnea and a 20-ppb increase in bedroom NO2 concentration was associated with an increased risk of having any exacerbation (OR, 1.90; P = 0.03) and severe exacerbations (OR, 2.16; P = 0.03). NO2 concentrations were not associated with other respiratory symptoms or lung function. There were no effect modifications between pollutants or by sex identified.

Multivariate analyses

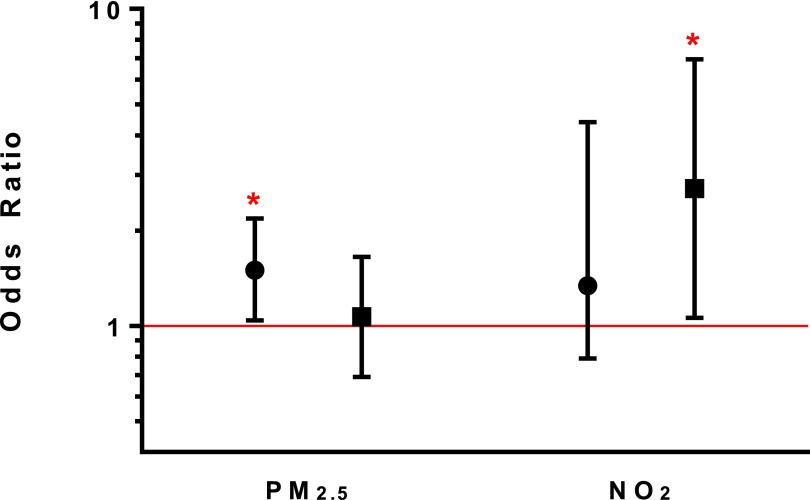

In models including both pollutants of interest (PM2.5 and NO2) and potential confounders, increasing PM2.5 concentrations in the main living area continued to be independently associated with increased wheeze, rescue medication use, and increased risk of nocturnal symptoms and severe exacerbations (Table 2). Specifically, a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentration in the main living area was associated with a 50% higher odds of having a severe exacerbation (OR, 1.50; P = 0.03) (Figure 1). Higher PM2.5 concentrations in the main living area had a borderline association with worse quality of life (β = 1.52; P = 0.05), but were not associated with cough, sputum production, or lung function. Within-person variability in PM2.5 exposure remained an independent predictor of wheeze and frequency of inhaler use, despite adjusting for mean concentration of PM2.5 across all study visits. Similarly, a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentrations between visits had a similar effect (OR) on risk of nocturnal symptoms and severe exacerbations as compared with a 10 μg/m3 difference in overall mean PM2.5 concentration between homes (see Table E2). Bedroom PM2.5 concentrations continued to demonstrate no association with any measured respiratory outcomes (see Table E3).

TABLE 2.

MULTIVARIATE ANALYSES OF ASSOCIATION OF INCREASING PM2.5 AND NO2 CONCENTRATIONS IN MAIN LIVING AREA WITH HEALTH OUTCOMES IN FORMER SMOKERS WITH CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

| |

Per 10 μg/m3 Increase in PM2.5 |

Per 20 ppb Increase NO2 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P Value | 95% CI | β | P Value | 95% CI | ||||||

| |

Lung Function |

||||||||||

| FEV1 % predicted |

0.20 |

0.70 |

(−0.82 to 1.22) |

1.06 |

0.19 |

(0.54 to 2.66) |

|||||

| |

Respiratory Symptoms |

||||||||||

| MMRC (dyspnea) |

0.11 |

0.06 |

(0.006 to 0.24) |

0.42 |

<0.001 |

(0.19 to 0.65) |

|||||

| Wheeze |

0.27 |

0.001 |

(0.11 to 0.43) |

−0.19 |

0.24 |

(−0.51 to 0.13) |

|||||

| Nocturnal symptoms (OR) |

1.44 |

0.01 |

(1.08 to 1.93) |

1.12 |

0.72 |

(0.59 to 2.14) |

|||||

| Usual cough (OR) |

1.05 |

0.75 |

(0.79 to 1.39) |

0.98 |

0.89 |

(0.56 to 1.65) |

|||||

| Usual phlegm (OR) |

1.26 |

0.09 |

(0.96 to 1.64) |

0.74 |

0.24 |

(0.44 to 1.22) |

|||||

| |

Rescue Medication Use |

||||||||||

| Frequency of inhaler use |

0.11 |

0.01 |

(0.02 to 0.20) |

0.18 |

0.02 |

(0.03 to 0.32) |

|||||

| |

Quality of Life |

||||||||||

| SGRQ |

1.52 |

0.05 |

(−0.00 to 3.04) |

0.93 |

0.48 |

(−1.67 to 3.53) |

|||||

| |

Exacerbations |

||||||||||

| |

OR |

P Value |

95% CI |

OR |

P Value |

95% CI |

|||||

| Any exacerbations |

1.05 |

0.79 |

(0.73 to 1.50) |

1.15 |

0.67 |

(0.61 to 2.17) |

|||||

| Severe exacerbations | 1.50 | 0.03 | (1.04 to 2.18) | 1.86 | 0.16 | (0.79 to 4.40) | |||||

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; MMRC = Modified Medical Research Council; OR = odds ratio; PM2.5 = particulate matter with aerodynamic size less than or equal to 2.5 μm; SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Adjusted models include adjustment for age, sex, education, season of sampling, and baseline prebronchodilator % predicted FEV1. Lung function models do not adjust for baseline FEV1. PM2.5 and NO2 were included in models simultaneously to account for independent effects of each pollutant.

Figure 1.

Particulate matter with aerodynamic size less than or equal to 2.5 μm (PM2.5) and NO2 concentrations associated with severe exacerbations. Adjusted models include adjustment for age, sex, education, season of sampling, and baseline prebronchodilator % predicted FEV1. PM2.5 and NO2 were included in models simultaneously to account for independent effects of each pollutant. Bedroom and main living area models run separately. Circles represent odds ratios in the main living area; squares represent odds ratios in the bedroom. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals. *P < 0.05.

Higher NO2 concentrations in the main living area were associated with increased dyspnea and increased rescue medication use (Table 2). NO2 variability during the study period seemed to be the more important predictor of dyspnea and frequency of inhaler use as compared with overall mean NO2 concentration (see Table E2). Higher bedroom NO2 concentrations were associated with increased risk of nocturnal awakenings (OR, 2.54; P = 0.03) and severe exacerbations (OR, 2.71; P = 0.04) (Figure 1; see Table E3). NO2 concentrations were not associated with lung function.

There was no evidence of interaction between the two pollutants in either location, and the association of pollutant concentrations with health outcomes was not significantly different after adjusting for the presence of SHS exposure, as determined by the presence of hair nicotine or baseline air nicotine (see Table E4).

Discussion

In this U.S. population of former smokers with moderate-to-severe COPD, higher indoor PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations were associated with worse COPD health, including increased respiratory symptoms and risk of severe exacerbations, suggesting that indoor pollutants may be important drivers of COPD morbidity. Specifically, in-home PM2.5 concentrations measured in the main living area were independently associated with increased respiratory symptoms, rescue medication use, and risk of severe exacerbations. Higher NO2 concentrations measured in these rooms were independently linked to increased dyspnea and rescue medication use, and higher NO2 concentrations in the bedroom were associated with increased risk of nocturnal awakenings and severe exacerbations caused by COPD. The consistent association between pollutant concentrations and respiratory morbidity was evident despite an overall low pollutant burden, suggesting that patients with COPD are particularly susceptible to even low levels of exposure. In addition, our results suggest that both overall pollutant burden within a home and changing concentrations over time contribute to morbidity. These findings suggest that indoor air pollution, a highly modifiable exposure, may play a substantive role in respiratory health of patients with COPD.

Evidence from international studies in developing countries and several U.S. studies shows that high concentrations of air pollution from indoor burning of biomass fuels cause and exacerbate existing COPD (24). To our knowledge, few studies have examined the effect of indoor air quality on COPD morbidity in developed countries, where pollutant burden may be substantially lower; in addition, these studies have focused on quality of life or lung function and are limited by their small sample size or cross-sectional study design, obscuring the effect of indoor air quality on COPD health (22–28). For example, results from a cross-sectional study by Osman and coworkers (26) suggest that indoor PM2.5 concentrations are associated with worse quality of life in patients with COPD. A study including 35 subjects with COPD showed no association between indoor air quality and lung function, with no assessment of other clinical outcomes (27). Another small panel study including 17 subjects with COPD showed no association between PM2.5 and PM2.5–10 with lung function over 12 days (28). Our study addresses a significant gap in the evidence by investigating longitudinal health effects of indoor air quality in patients with COPD with repeated comprehensive clinical assessments, including lung function, respiratory symptoms, quality of life, and exacerbations.

In our study, mean indoor PM2.5 concentrations were approximately 12 μg/m3 in the bedroom and main living area. Although these PM concentrations are relatively low, studies show that even low levels of exposure have clinical effects. For example, outdoor PM2.5 concentrations were associated with mortality with a linear concentration-response relationship down to PM2.5 concentrations of 8 µg/m3 (29). Because Americans spend most of their time indoors, and individuals with COPD spend more time at home than their age-matched counterparts (9), it is critical to understand the health effects of indoor pollutant exposure. Our results show a consistent association between PM2.5 concentrations in the main living area and respiratory symptoms, including worse dyspnea, increased risk of nocturnal symptoms, and increased frequency of wheeze and rescue medication use. Higher PM2.5 concentrations also had a borderline association with worse quality of life and, importantly, higher PM2.5 concentrations were associated with increased risk of severe exacerbations. For instance, a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentrations was associated with a 44% higher odds of having nocturnal symptoms and a 50% higher odds of having a severe COPD exacerbation. Based on the risk of severe exacerbations in our study population of 38% per year, we would predict that the risk of a severe exacerbation would be 9.9% higher (range of error in that estimate being 1–19%) if PM2.5 concentrations in a home were 10 μg/m3 higher.

We did not find an association between PM2.5 concentrations in the bedroom and respiratory morbidity. The reason for the difference in effect of exposure between rooms is not completely clear. One possibility is that the differing results between rooms are a spurious finding caused by modest sample size. The reason our study was explicitly designed to investigate the health effect of pollutants from each room separately was that we expected variations in pollutant concentrations between rooms may exist, and people may spend varying amounts of time within various rooms (30, 31). Despite overall similar average concentrations, it is possible that the PM characteristics may differ between the bedroom and living areas. Furthermore, the main living area may represent the location where subjects are awake and active, therefore having higher minute ventilation and increased particle deposition (32), and subsequently increased susceptibility to adverse effects of pollutant exposure. We found no link between pollutant concentrations and changes in lung function, similar to results of previous studies showing no clear association between indoor PM and lung function in few patients with COPD (27, 28).

NO2, a by-product of combustion with indoor sources including gas-burning appliances, may lead to worse respiratory health through airway epithelial damage, or lowering the threshold for viral-induced exacerbations (33, 34). A cross-sectional study by Osman and coworkers (26) found no association between indoor NO2 concentrations and worse quality of life in subjects with COPD. Although our longitudinal study also did not show a significant association between NO2 concentrations and quality of life, we found a link between indoor NO2 concentrations in the main living area and increased dyspnea and higher rescue medication use. Bedroom NO2 concentrations were also associated with higher risk of nocturnal symptoms and severe COPD exacerbations, and this adverse effect of NO2 was independent of PM exposure.

Although SHS exposure has been associated with worse COPD health and greater risk of COPD exacerbations (35, 36), it did not likely explain our findings. We showed a consistent association with PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations with poor respiratory health in homes where SHS exposure was relatively low. Almost half of homes did not have detectable air nicotine levels at baseline, and among the homes that had detectable levels of air nicotine, average levels were relatively low (37). The lack of correlation between reported SHS and airborne nicotine concentrations is consistent with literature suggesting that self-report of SHS often has low reliability (37). In addition, in our homes with detectable air nicotine, the concentrations were quite low and were equivalent to what one would expect from one to two cigarettes per day being smoked in the home (38). These concentrations are not inconsistent with an occasional visitor (nonresident) smoking in the house. In addition, hair nicotine estimates personal SHS exposure over the last 3 months, and may represent exposures occurring outside the home. Hair nicotine concentrations can vary depending on the amount of time spent in the home when a smoker is present; time spent around smokers outside the home; absorption of nicotine from surfaces (so-called third-hand tobacco exposure); the race of the participant; and the presence or absence of hair treatments (38, 39). In our study we chose a comprehensive assessment of potential exposure to SHS that included self-reporting; airborne nicotine concentrations in the home; and a biomarker of exposure (hair nicotine). Adjusting our analyses for SHS assessed by either the presence of detectable hair or air nicotine did not materially change our results.

The limitations of our study warrant consideration. Our results are derived from a population in Baltimore City and surrounding areas and the indoor environment may not be generalizable to other communities. In addition, we did not measure outdoor or personal exposure to PM and NO2; however, previous results from Baltimore City homes show that although outdoor PM and NO2 concentrations contribute to indoor concentrations, indoor sources, such as smoking, cooking, combustion sources, and cleaning practices, are the dominant determinants of indoor pollutant concentrations (20, 40). To confirm a similar association in our sample of homes of subjects with COPD, in a subgroup (n = 26) of our participants who lived within 3 miles of an outdoor monitoring station, we found that outdoor PM2.5 concentrations explained only 5% of the variance in indoor PM2.5 concentrations; outdoor NO2 concentrations explained approximately 25% of the variance in indoor NO2 concentrations. A small study of 10 subjects with COPD in Boston showed that indoor PM concentrations explained between 40 and 91% of the variability in personal exposures and were strongest for PM2.5 (41). In addition, misclassification of personal exposure would likely bias our results toward the null. Despite our modest sample size, we found consistent results with PM2.5 concentrations in the main living area and respiratory health, strengthening the validity of our results.

To our knowledge, our study is the first longitudinal study specifically investigating the adverse respiratory health effects of indoor air pollutant exposure on COPD morbidity in a developed country. We show that indoor pollutant exposure, including PM2.5 and NO2, is associated with increased respiratory symptoms and risk of COPD exacerbations in former smokers with moderate to severe COPD. In addition, our data suggest that overall pollutant burden within a home and changing concentrations over time contribute to morbidity. Current recommendations for improving home indoor air quality focus mostly on avoiding indoor SHS. However, our findings are likely independent of SHS exposure, and there are other important modifiable sources of indoor PM and NO2 (20, 40). Future studies investigating the effectiveness of environmental interventions aimed at reducing indoor pollutant concentrations in homes of patients with COPD, such air cleaner intervention trials that have shown reduction in indoor PM and improved symptoms in asthma (10), are warranted as potential nonpharmacologic approaches to improving COPD health. They may represent more cost-effective and novel therapeutic arenas for a disease with limited treatment options.

Footnotes

Supported by grants by NIEHS (ES01578, ES003819, ES015903, ES018176, and ES016819) and the Environmental Protection Agency (RD83451001).

Author Contributions: N.N.H., M.C.M., G.B.D., and P.N.B. provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. A.J.B., R.D.P., E.C.M., L.P., and C.A. contributed to data analysis and interpretation of data. D.L.W. contributed to data acquisition. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1987OC on March 22, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance—United States, 1971–2000. Respir Care. 2002;47:1184–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominici F, Peng RD, Bell ML, Pham L, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA. 2006;295:1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peacock JL, Anderson HR, Bremner SA, Marston L, Seemungal TA, Strachan DP, Wedzicha JA. Outdoor air pollution and respiratory health in patients with COPD. Thorax. 2011;66:591–596. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.155358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naess O, Nafstad P, Aamodt G, Claussen B, Rosland P. Relation between concentration of air pollution and cause-specific mortality: four-year exposures to nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter pollutants in 470 neighborhoods in Oslo, Norway. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:435–443. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen ZJ, Hvidberg M, Jensen SS, Ketzel M, Loft S, Sorensen M, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Raaschou-Nielsen O. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:455–461. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0937OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (revised 2011). 1–90. 2011 [accessed 2012]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com

- 8.Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, Robinson JP, Tsang AM, Switzer P, Behar JV, Hern SC, Engelmann WH. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11:231–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leech JA, Smith-Doiron M. Exposure time and place: do COPD patients differ from the general population? J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2006;16:238–241. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butz AM, Matsui EC, Breysse P, Curtin-Brosnan J, Eggleston P, Diette G, Williams D, Yuan J, Bernert JT, Rand C. A randomized trial of air cleaners and a health coach to improve indoor air quality for inner-city children with asthma and secondhand smoke exposure. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:741–748. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belli AJ, McCormack MC, Breysse PN, Matsui EC, Diette GB, Williams DL, Aloe C, Curtin-Brosnan J, Peng RD, Paulin LM, et al. Indoor particulate matter concentrations are associated with worse respiratory health in former smokers with COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A6633. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulin LM, McCormack MC, Diette GB, Belli AJ, Williams D, Matsui EC, Curtin-Brosnan J, Aloe C, Peng RD, Breysse P, et al. Indoor nitrogen dioxide concentrations are associated with worsening dyspnea in former smokers with COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A6633. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middleton ET, Morice AH. Breath carbon monoxide as an indication of smoking habit. Chest. 2000;117:758–763. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.3.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr JT, Schumacher GE, Freeman S, LeMoine M, Bakst AW, Jones PW. American translation, modification, and validation of the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Clin Ther. 2000;22:1121–1145. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:581–586. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general US population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han MK, Kazerooni EA, Lynch DA, Liu LX, Murray S, Curtis JL, Criner GJ, Kim V, Bowler RP, Hanania NA, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in the COPDGene study: associated radiologic phenotypes. Radiology. 2011;261:274–282. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansel NN, Breysse PN, McCormack MC, Matsui EC, Curtin-Brosnan J, Williams DL, Moore JL, Cuhran JL, Diette GB. A longitudinal study of indoor nitrogen dioxide levels and respiratory symptoms in inner-city children with asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1428–1432. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmes ED, Gunnison AF, DiMattio J, Tomczyk C. Personal sampler for nitrogen dioxide. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1976;37:570–577. doi: 10.1080/0002889768507522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond SK, Leaderer BP. A diffusion monitor to measure exposure to passive smoking. Environ Sci Technol. 1987;21:494–497. doi: 10.1021/es00159a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger S. The analysis of longitudinal data, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 24.Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fong KN, Mui KW, Chan WY, Wong LT. Air quality influence on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients' quality of life. Indoor Air. 2010;20:434–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osman LM, Douglas JG, Garden C, Reglitz K, Lyon J, Gordon S, Ayres JG. Indoor air quality in homes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:465–472. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-589OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Hartog JJ, Ayres JG, Karakatsani A, Analitis A, Brink HT, Hameri K, Harrison R, Katsouyanni K, Kotronarou A, Kavouras I, et al. Lung function and indicators of exposure to indoor and outdoor particulate matter among asthma and COPD patients. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:2–10. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.040857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu SO, Ito K, Lippmann M. Effects of thoracic and fine PM and their components on heart rate and pulmonary function in COPD patients. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2011;21:464–472. doi: 10.1038/jes.2011.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lepeule J, Laden F, Dockery D, Schwartz J. 120:965–970. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104660. Chronic exposure to fine particles and mortality: an extended follow-up of the Harvard Six Cities Study from 1974 to 2009. Environ Health Perspect 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones J, Stick S, Dingle P, Franklin P. Spatial variability of particulates in homes: implications for infant exposure. Sci Total Environ. 2007;376:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ju C, Spengler JD. Room-to-room variations in concentration of respirable particles in residences. Environ Sci Technol. 1981;15:592–596. doi: 10.1021/es00087a600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daigle CC, Chalupa DC, Gibb FR, Morrow PE, Oberdorster G, Utell MJ, Frampton MW. Ultrafine particle deposition in humans during rest and exercise. Inhal Toxicol. 2003;15:539–552. doi: 10.1080/08958370304468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chauhan AJ, Inskip HM, Linaker CH, Smith S, Schreiber J, Johnston SL, Holgate ST. Personal exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and the severity of virus-induced asthma in children. Lancet. 2003;361:1939–1944. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13582-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persinger RL, Poynter ME, Ckless K, Janssen-Heininger YM. Molecular mechanisms of nitrogen dioxide induced epithelial injury in the lung. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;234–235:71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin P, Jiang CQ, Cheng KK, Lam TH, Lam KH, Miller MR, Zhang WS, Thomas GN, Adab P. Passive smoking exposure and risk of COPD among adults in China: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Lancet. 2007;370:751–757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisner MD, Iribarren C, Yelin EH, Sidney S, Katz PP, Sanchez G, Blanc PD. The impact of SHS exposure on health status and exacerbations among patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:169–176. doi: 10.2147/copd.s4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butz AM, Breysse P, Rand C, Curtin-Brosnan J, Eggleston P, Diette GB, Williams D, Bernert JT, Matsui EC. Household smoking behavior: effects on indoor air quality and health of urban children with asthma. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:460–468. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0606-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Apelberg BJ, Hepp LM, Avila-Tang E, Gundel L, Hammond SK, Hovell MF, Hyland A, Klepeis NE, Madsen CC, Navas-Acien A, et al. Environmental monitoring of secondhand smoke exposure. Tob Control. 2013;22:147–155. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim S, Wipfli H, Navas-Acien A, Dominici F, Avila-Tang E, Onicescu G, Breysse P, Samet JM. Determinants of hair nicotine concentrations in nonsmoking women and children: a multicountry study of secondhand smoke exposure in homes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3407–3414. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCormack MC, Breysse PN, Hansel NN, Matsui EC, Tonorezos ES, Curtin-Brosnan J, Williams DL, Buckley TJ, Eggleston PA, Diette GB. Common household activities are associated with elevated particulate matter concentrations in bedrooms of inner-city Baltimore pre-school children. Environ Res. 2008;106:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rojas-Bracho L, Suh HH, Koutrakis P. Relationships among personal, indoor, and outdoor fine and coarse particle concentrations for individuals with COPD. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2000;10:294–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]