Abstract

In the context of future adeno-associated viral (AAV)–based clinical trials for Duchenne myopathy, AAV genome fate in dystrophic muscles is of importance considering the viral capsid immunogenicity that prohibits recurring treatments. We showed that AAV genomes encoding non-therapeutic U7 were lost from mdx dystrophic muscles within 3 weeks after intramuscular injection. In contrast, AAV genomes encoding U7ex23 restoring expression of a slightly shortened dystrophin were maintained endorsing that the arrest of the dystrophic process is crucial for maintaining viral genomes in transduced fibers. Indeed, muscles treated with low doses of AAV-U7ex23, resulting in sub-optimal exon skipping, displayed much lower titers of viral genomes, showing that sub-optimal dystrophin restoration does not prevent AAV genome loss. We also followed therapeutic viral genomes in severe dystrophic dKO mice over time after systemic treatment with scAAV9-U7ex23. Dystrophin restoration decreased significantly between 3 and 12 months in various skeletal muscles, which was correlated with important viral genome loss, except in the heart. Altogether, these data show that the success of future AAV-U7 therapy for Duchenne patients would require optimal doses of AAV-U7 to induce substantial levels of dystrophin to stabilize the treated fibers and maintain the long lasting effect of the treatment.

Introduction

The dystrophinopathies are pathologies caused by anomalies in the DMD gene that encodes a subsarcolemmal protein called dystrophin. This protein is absent in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), whereas it is present but qualitatively and/or quantitatively altered in the more moderate Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD). This clinical heterogeneity is the result of the genetic heterogeneity of the mutations in the DMD gene (2.4 Mb, 79 exons). With regard to the large deletions, the most frequent genetic alteration, the severity of the phenotype is primarily conditioned by the impact of the mutation on the protein reading frame of the dystrophin transcript. It is known that the modular structure of the dystrophin (central rod-domain made of 24 spectrin-like repeats) tolerates large internal deletions.1 This observation led to the development of two main therapeutic strategies: classical gene therapy with transfer of functional mini- or micro-dystrophin cDNAs in muscles, and targeted exon skipping. Both approaches have shown encouraging results using adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors, which allow efficient gene transfer into muscles. Although exon-skipping strategies have demonstrated some success using antisense oligonucleotides, in particular in recent clinical studies,2,3 we and others have also shown that the antisense sequences could be disguised in a small nuclear RNA such as U7 snRNA or U1 snRNA.4,5,6 These therapeutic molecules can be vectorized in lentivectors as well as in AAV vectors, which ensures a permanent production of the therapeutic antisense in transduced cells. The effectiveness of these approaches has been validated ex vivo (myoblasts of DMD patients in culture transduced with lentivectors expressing U7 snRNA)7,8 and in vivo (intramuscular or intravascular injections of AAV-U7 or -1 snRNA) using DMD murine models5,6,9 as well as the canine GRMD.10,11 These preclinical data made the rationale of engrafting an antisense factory within dystrophic fibers by means of gene therapy very attractive. Indeed, a single treatment was sufficient to attain substantial levels of restored dystrophin, which was associated with a significant improvement of the muscle force.

AAV-mediated gene transfer holds promise as a treatment for DMD, particularly because of its efficacy and persistence in transduced tissues. Viral genomes might clearly persist in normal muscles for several years as non-integrative episomal chromatin, as previously shown in primates.12,13 However, one must remain cautious regarding their persistence in dystrophic muscle as the beneficial expression of the antisense may disappear over time as observed recently in both severe dystrophic mice and GRMD dogs treated with AAV-U7.9,11 In the context of clinical trials with AAV-U7 and AAV-mini-dystrophin for Duchenne myopathy, this genome loss over time might represent a significant complication or at least be challenging considering that vectors capsids are immunogenic rendering recurring treatments unlikely.14

As muscular dystrophies are characterized by repeated cycles of necrosis-regeneration, we hypothesized that AAV episomal genomes could be lost throughout this process. We thus investigated AAV genome fate in dystrophic muscles by quantifying AAV genome copy numbers after AAV-U7 injections in two dystrophin-deficient mouse models, mdx and dystrophin/utrophin double-knockout (dKO), compared with wild-type mice. The mdx mouse, which is historically the primary animal model for DMD, presents histological signs of muscular dystrophy, but has little muscle weakness and relatively normal life span whereas the dKO mouse suffers from a much more severe and progressive muscle wasting.15,16 Here, we demonstrate that non-therapeutic AAV genomes are drastically and rapidly lost from moderately dystrophic mdx muscles in contrast to therapeutic AAV genomes allowing optimal dystrophin rescue. We observed a similar loss of vector genomes in cardiotoxin-treated normal muscles suggesting that muscle necrosis-regeneration was the most likely cause of this loss. We also followed AAV therapeutic genomes after systemic injection into dKO mice and showed that even the therapeutic AAV genomes were lost over time in severe dystrophic muscles. Without calling into question the future development of gene therapy for DMD, we demonstrate that optimal restoration of dystrophin will be required to protect dystrophic muscles from their pathological turn-over. If not, the inexorable loss of the therapeutic gene will at best endow only a transient improvement.

Results

Rescue of high level of dystrophin prevents AAV genome loss in mdx muscles

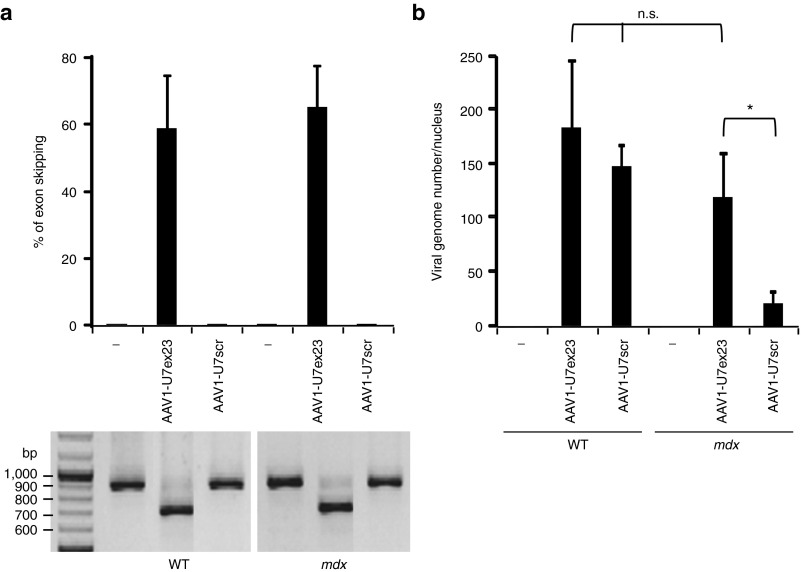

We first investigated the fate of therapeutic versus non-therapeutic AAV vector genomes in wild-type (WT) and dystrophic muscles. For that purpose, we used an AAV1 vector encoding the U7ex23, allowing efficient exon 23 skipping and therefore dystrophin rescue, as a therapeutic vector (AAV1-U7ex23), and an AAV1-U7scr vector, carrying non specific sequences, unable to rescue dystrophin expression, as a non-therapeutic vector. High dose (1.2E+11 vg) of these vectors was injected into Tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of WT and mdx mice. Three weeks after injection, exon 23 skipped DMD transcripts were detected by nested RT-PCR and quantified by relative TaqMan quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Figure 1a). Levels of exon 23 skipping in AAV1-U7ex23 injected TAs were similar in WT and mdx mice (58% versus 64%) and, as expected, null in AAV1-U7scr injected TAs. After AAV1-U7ex23 injection, AAV genome copy number quantified by absolute SYBR Green qPCR was not significantly different in WT and mdx muscles (Figure 1b, 182 vg/nucleus versus 119), showing that AAV1 transduction efficiency is similar in WT and mdx muscles. Western blotting analysis showed that dystrophin was expressed at nearly 50% of the normal level in AAV-U7ex23 mdx injected muscles (Figure 2b, high). Conversely, AAV genome copy number was seven times higher in AAV-U7scr WT muscles than in mdx ones (147 vg/nucleus versus 20), showing that non-therapeutic AAV genomes are drastically lost within 3 weeks after injection in mdx muscles. This loss is however prevented when dystrophin is rescued in mdx TAs by the therapeutic AAV1-U7ex23 (119 vg/nucleus versus 20 in AAV-U7scr mdx muscles).

Figure 1.

Therapeutic and non-therapeutic adeno-associated viral (AAV) genome fate in dystrophic muscles. Tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of wild-type (WT) and mdx mice were injected with 1.2E+11 viral genomes (vg) of AAV1-U7ex23, AAV1-U7scr or PBS1X (-). The mice were killed 3 weeks later. (a) Estimation of exon 23–skipping level by nested RT-PCR (lower panel). The 901 bp PCR product corresponds to full-length dystrophin transcripts whereas the 688 bp product corresponds to transcripts lacking exon 23. The quantification of exon 23 skipping (upper panel) was performed by relative TaqMan qPCR and expressed as a percentage of total dystrophin transcripts. (b) Quantification of AAV vg by absolute SYBR Green qPCR. AAV genome copy number is expressed as an absolute value per diploid nucleus. The data represent the mean values of three muscles per group ± SEM. One of two representative experiments is shown. *P ≤ 0.05, Student's t-test. n.s., non significant.

Figure 2.

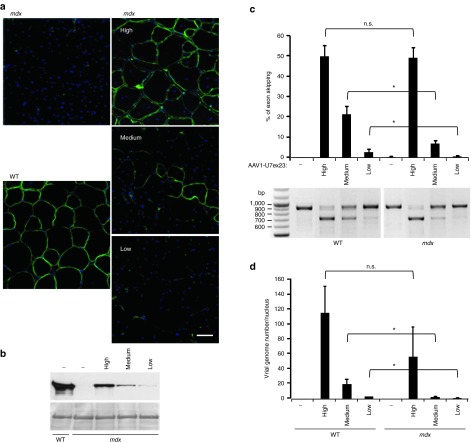

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) genome fate in AAV1-U7ex23 dose escalation study. Tibialis anterior (TAs) of wild-type (WT) and mdx mice were injected with 1.2E+11 vg (high dose), 3E+10 vg (medium dose) or 7.5E+09 vg (low dose) of AAV1-U7ex23 or PBS1X (-). The mice were killed 3 weeks later. (a) Dystrophin rescue was monitored by immunostaining with the anti-dystrophin rabbit polyclonal antibody on transverse sections of TA muscles. One representative immunostained section of three different muscles is shown for each condition. (b) Evaluation of dystrophin levels in mdx muscles by western blotting with NCL-DYS1 monoclonal antibody (upper panel). The membrane was also stained with Ponceau (lower panel). (c) Estimation of exon 23–skipping level by nested RT-PCR (lower panel). The 901 bp PCR product corresponds to full-length dystrophin transcripts whereas the 688 bp product corresponds to transcripts lacking exon 23. The quantification of exon 23 skipping (upper panel) was performed by relative TaqMan qPCR and expressed as a percentage of total dystrophin transcripts. (d) Quantification of AAV vg by absolute SYBR Green qPCR. AAV genome copy number is expressed as an absolute value per diploid nucleus. The data represent the mean values of three TAs per group ± SEM. One of two representative experiments is shown. *P ≤ 0.05, Student's t-test. n.s., non significant.

Viral genomes are poorly maintained in partially rescued mdx muscles

To investigate the fate of therapeutic AAV genomes when the dystrophin rescue is only partial, we injected lower doses of AAV1-U7ex23 in WT and mdx muscles: 1/4 (medium, 3E+10 vg) and 1/16 (low, 7.5E+09 vg) of the optimal dose (high, 1.2E+11 vg). Three weeks after injection, immunofluorescence staining revealed partial dystrophin restoration in mdx injected muscles and its correct localization at the sarcolemma (Figure 2a). Dystrophin levels were quantified in mdx muscles by western blotting and showed that high, medium and low doses injections led respectively to 49.8, 13.8, and 0.13% of normal dystrophin level (Figure 2b). As shown previously, a high dose of AAV1-U7ex23 allowed a strong exon 23 skipping, around 50%, in both WT and dystrophic muscles (Figure 2c). At medium dose, this level dropped down to 21.5% in WT muscle and 6.8% in dystrophic muscle. At low dose, the difference in exon-skipping efficacy was even higher as it was four times lower in mdx TAs than in WT ones (2.8% versus 0.6%). Consistent with these results, in high-dose injected TAs, the genome copy numbers were not significantly different in the two muscular contexts (Figure 2d, 116 vg/nucleus versus 57), whereas in medium and low-dose injected TAs, seven times more genome copies were detected in WT muscles versus dystrophic (respectively, 19.7 vg/nucleus versus 2.5, and 2.6 versus 0.4). These results suggest that viral genomes are poorly maintained in muscle fibers when the dystrophin rescue is partial at the sarcolemma, which could be explained by the cycles of necrosis and regeneration still occurring in the non (or only partially) corrected dystrophic muscle.

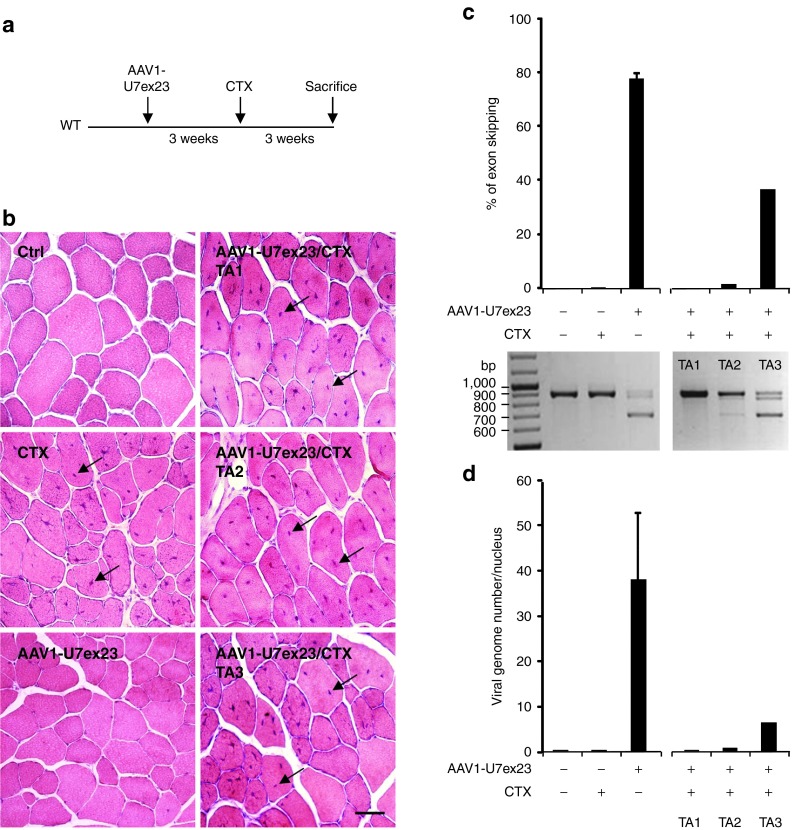

AAV viral genomes are cleared from WT muscles by cardiotoxin treatment

To investigate further the viral genome fate in the context of muscle degeneration and regeneration, we used an artificial model of muscle injury by cardiotoxin injection. Cardiotoxin is a peptide isolated from snake venom that causes depolarization and contraction of muscle fibers leading to cell death via inhibition of protein kinase C.17 WT TAs were injected with 1.2E+11 vg of AAV1-U7ex23 and 3 weeks later with cardiotoxin to induce muscle degeneration (CTX, Figure 3a). Three weeks after CTX injection, muscle damage was evaluated by calculating the percentage of centronucleation in muscle sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Forty to 80% of the nuclei were in a central position in CTX-injected TAs that received AAV1-U7ex23 (AAV1-U7ex23/CTX in Figure 3b) or not (CTX) 3 weeks before. For AAV1-U7ex23/CTX injected TAs, sections from three different muscles are represented: TA1 and TA2 with 80% of centronucleation and TA3 with 37%. In this experiment, a mean value of 78% of DMD transcripts were skipped in TAs injected with AAV1-U7ex23 only, whereas in TAs injected with AAV1-U7ex23 and CTX, it dropped down to 3% for TA1 and TA2, and 37% for TA3 (Figure 3c). Interestingly, this drastic decrease in exon 23–skipping efficiency was nicely correlated to the number of viral genomes: an average of 38 vg per nucleus were detected in AAV1-U7ex23 injected TAs whereas in AAV1-U7ex23/CTX-injected TAs this number was close to zero for TA1 and TA2 and six for TA3 (Figure 3d). Hence, the CTX-induced muscle regeneration is accompanied by a drastic loss of AAV genomes from muscle fibers and a decrease in the exon-skipping therapeutic effect, confirming that muscle degeneration/regeneration in dystrophic muscles may be the cause for viral genome loss.

Figure 3.

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) genome fate in cardiotoxin-injured muscles. (a) Tibialis anterior (TAs) of wild-type (WT) mice were first injected with 1.2E+11 vg of AAV1-U7ex23 or PBS1X (-). Three weeks later, the same muscles were injected with 0.5 nmol of cardiotoxin (CTX) or PBS1X (-). The mice were killed 3 weeks after the second injection. (b) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of TA transversal sections. Ctrl, TA injected twice with PBS1X; AAV1-U7ex23, TA injected with AAV1-U7ex23 and PBS1X; CTX, TA injected with PBS1X and CTX; AAV1-U7ex23/CTX, TA injected with AAV1-U7ex23 and CTX. Arrows indicate internal nuclei. Scale bar = 100 µm. (c) Estimation of exon 23–skipping level by nested RT-PCR (lower panel). The 901 bp PCR product corresponds to full-length dystrophin transcripts whereas the 688 bp product corresponds to transcripts lacking exon 23. The quantification of exon 23 skipping (upper panel) was performed by relative TaqMan qPCR and expressed as a percentage of total dystrophin transcripts. The data represent the mean values of three muscles per group ± SEM for Ctrl, CTX and AAV1-U7ex23 injected TAs, whereas individual results are presented for three TAs injected with AAV1-U7ex23 and CTX. (d) Quantification of AAV vg by absolute SYBR Green qPCR. AAV genome copy number is expressed as an absolute value per diploid nucleus. The data represent the mean values of three muscles per group ± SEM for Ctrl, CTX and AAV1-U7ex23 injected TAs, whereas individual results are presented for three TAs injected with AAV1-U7ex23 and CTX.

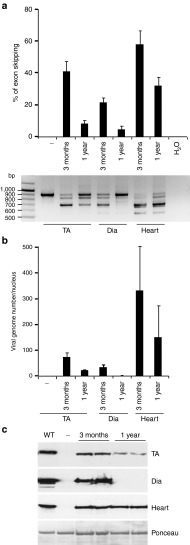

Loss of therapeutic vector genome over time in dKO mice

To evaluate the long term effect of this muscle degeneration/regeneration on a therapeutically relevant mouse model, we studied the fate of viral genomes over time in the severe double knock-out mouse model. The dKO mouse suffers from a much more severe and progressive muscle wasting than the mdx mouse, impaired mobility and premature death, similar to DMD patients. We recently showed that a single intravenous injection of scAAV9-U7ex23 in dKO mice induced near-normal levels of dystrophin expression in all muscles examined and resulted in a considerable improvement of their muscle function and dystrophic pathology.9 Although the lifespan of the treated dKO mice was remarkably extended, mice still died at ~1 year of age. We investigate here the fate of viral genomes in the TA, diaphragm and cardiac muscles of scAAV9-U7ex23 treated dKO mice at 3 months and 1 year of age. Analysis of muscles from treated dKO mice close to the end point revealed that exon 23 skipping and dystrophin expression had decreased drastically in TA and diaphragm compared with the levels observed at 3 months of age, i.e., 10 weeks after the injection (Figure 4a,c). These levels were particularly low in the diaphragm, where dystrophin restoration was no longer detectable by western blot. In contrast, exon 23 skipping and dystrophin restoration levels were still fairly high in the heart, albeit lower than that observed at 3 months of age. These observations correlate nicely to the number of viral genomes detected, which were much higher in the heart than in the TA and diaphragm at 1 year of age (Figure 4b). Although the viral genome copy number was only two times lower in the heart, it was more than three times lower in TA and 30 times lower in diaphragm. These results show that even therapeutic AAV genomes are lost over time in severe dystrophic muscles and suggest that the rate of this loss is correlated with the original levels of dystrophin restoration.

Figure 4.

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) genome fate in dKO mice injected systemically with scAAV9-U7ex23. dKO mice were injected intravenously with approximately 1E+13 vg of scAAV9-U7ex23 and Tibialis anterior (TA), diaphragm and cardiac muscles were analyzed 3 months and 1 year after the injection. (a) Estimation of exon 23–skipping level by nested RT-PCR (lower panel). The 901 bp PCR product corresponds to full-length dystrophin transcripts whereas the 688 bp product corresponds to transcripts lacking exon 23. The quantification of exon 23 skipping (upper panel) was performed by relative TaqMan qPCR and expressed as a percentage of total dystrophin transcripts. (b) Quantification of AAV vg by absolute SYBR Green qPCR. AAV genome copy number is expressed as an absolute value per diploid nucleus. (c) Evaluation of dystrophin levels in dKO muscles by western blotting with NCL-DYS1 monoclonal antibody (upper panels). The membrane was also stained with Ponceau (lower panel). The data represent the mean values of three muscles per group ± SEM for the 3-month-old mice and of two muscles for the two 1-year-old mice that survive after 1 year.

Discussion

In this study, we followed AAV genome fate in WT and dystrophic muscles by performing quantitative PCR on whole muscle extracts. Although this technique allows a global quantification of viral genome levels in muscle, we acknowledge that it cannot discriminate between the different molecular structures (intact or degraded molecules, genomic integrant or episomal monomer/concatemer, encapsidated or free) and their localization (inside or outside the muscle fiber, in the cytoplasm or the nucleus). We first established that AAV-U7ex23 transduction efficiency is similar in WT and mdx muscles, which allowed us to focus our attention on AAV genome persistence in dystrophic muscles.

In mdx mice, which have a rather mild muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy compared with that observed in DMD patients, we demonstrated that non-therapeutic viral genomes were drastically lost within 3 weeks after intramuscular injections compared with therapeutic AAV-U7 inducing dystrophin restoration. These results strongly suggested that dystrophin rescue is necessary for AAV genome maintenance in dystrophic muscle and were somehow expected since the restoration of dystrophin expression stabilizes the fiber, protecting it from contraction-induced damage and subsequent necrosis, with the consequence of both stopping degeneration-regeneration cycles and stabilizing the viral genomes. These observations are also in accordance with previously published observations indicating that the murine secreted alkaline phosphatase (muSeAP) level in blood obtained after injection of AAV-muSeAP into the muscle was very much lower in dystrophic than in WT mice.18 Upon treatment of the dystrophic muscle by gene transfer, the level of muSeAP was restored and correlated with the expression of the therapeutic transgene and with the level of muscle improvement. These results are of crucial importance when using AAV vectors in dystrophic muscle. Any potential therapeutic approaches using AAV delivery in dystrophic muscles would be less beneficial when dystrophin expression is only incompletely restored. For example, the inhibition of myostatin pathway enhances muscle growth and improves muscle force. In a study using RNA interference delivery via AAV injection in mdx muscles to downregulate AcvRIIb mRNA, it has been shown that the shRNA was much more efficient when the dystrophin was also restored, probably due to the decreased cellular turnover in these muscles.19 Therefore, one should be cautious when using AAV vectors to deliver not fully therapeutic genes to dystrophic muscle, as the gene transfer is likely to only be transient.

We also characterized in this study the therapeutic genome fate according to the dose injected and show that viral genomes were poorly maintained in muscle fibers when the dystrophin rescue at the sarcolemma was only partial. This could be intuitively explained by the poor protection of muscle fibers with low doses of vector against contraction-induced damage leading to subsequent necrosis and progressive loss of viral genomes. We observed a similar loss of vector genome in cardiotoxin-treated muscles confirming that muscle degeneration/regeneration was the most probable cause of this loss. It was particularly interesting to note that the TA muscle in which the damage had been less important (probably due to an unsuccessful cardiotoxin injection) presented higher levels of AAV genomes and therefore of exon skipping. However, we can't exclude that inflammation and fibrosis that are part of the degenerative process of the dystrophic muscle may participate also to the loss of viral genomes.

In the context of future clinical evaluation of the AAV-U7 approach in DMD patients, we wanted to investigate the long term effect of muscle degeneration/regeneration in a therapeutically relevant mouse model. We therefore studied the fate of viral genomes over time in the severe double knock-out mouse model following a single systemic injection of scAAV9-U7ex23. Although the treatment led to high and widespread levels of exon 23 skipping and dystrophin restoration 10 weeks after injection, these levels dramatically dropped 9 months later (at ~1 year of age). Interestingly, the loss of viral genome was particularly high in the diaphragm (30-fold decrease) which was also the least transduced muscle, suggesting that the lower the level of dystrophin restoration, the quicker it will be lost. This could also be explained by the severely affected nature of the diaphragm muscle in mouse models (both mdx and dKO), compared with the cardiac muscle which has much less regenerative capacity. These findings reveal that even though levels of transduction were originally quite strong allowing high and widespread restoration of dystrophin, the vector genomes are still progressively lost in severe dystrophic muscle. We believe that the decline we observed in dKO mice over time was due to the ongoing pathological process itself, which was not entirely stopped by expressing a truncated dystrophin that do not have the full functionality of a normal full-length dystrophin. Although expressing such a truncated dystrophin markedly improved muscle function, we must keep in mind that it merely converted transduced DMD fibers into BMD-like fibers, which are known to be less resilient than control fibers as very mild BMD patients still display elevated serum CK activities. In BMD, damaged fibers are replaced by new BMD fibers, whereas the same degenerating progression in AAV-transduced DMD muscles would gradually clear the cassette expressing U7-antisense, leading inexorably to the reconstitution of the original DMD phenotype.

Interestingly, Pacak et al.20 followed therapeutic AAV genome fate in another dystrophic context, the alpha-sarcoglycan (sgca) knockout mice, animal model of Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy Type 2D (LGMD 2D). Similarly to our own results, they observed the loss of vector genomes in skeletal muscles that were not protected by the benefits of therapeutic gene transfer. In their study, the therapeutic vector expressing the sgca protein led to a drastic reduction and nearly the elimination of the viral genome loss at 1 year after injection, whereas we showed a dramatic decrease of the number of viral genomes in the dKO mice over the same period of time. At the opposite of AAV-U7 treatment, AAV-sgca gene therapy produces full-length therapeutic protein—presumably more protective than truncated rescued protein—that could explain the better maintenance of viral genomes. In addition, AAV injections had occurred at the neonatal period, before the disease onset, when muscles have not yet undergone cycle of necrosis-regeneration. And finally, dKO mouse suffers from a much more severe and progressive muscle wasting than sgca KO mouse that could explain the differences observed between the two studies.

This loss of viral genome and therefore dystrophin over time highlights the need for readministration of AAV-U7 vector to achieve long-term or potential permanent therapeutic benefit in DMD patients. However, the immune response against the AAV capsid leading in particular to the production of neutralizing antibodies prohibits today any reinjection, posing a major issue for the therapeutic potential of the AAV-U7 approach. A functional miniaturized dystrophin transgene partially restored muscle force in DMD murine models.21,22,23 Nevertheless, in recent human trials with AAV-mediated mini-dystrophin delivery to DMD patient muscles, no mini-dystrophin transgene expression was detected.24 Conversely, the authors could detect dystrophin-specific T cells and speculated that T cells targeting self or non-self dystrophin epitopes may have eliminated mini-dystrophin expressing muscle fibers. In accordance with this comment, intramuscular injection to deliver AAV6-canine micro-dystrophin in cxmd dystrophic dogs along with a brief course of commonly used immunosuppressants allowed micro-dystrophin expression that was maintained for at least 18 months after discontinuing immunosuppression.25

In contrast to what we observed with AAV-U7, the antisense oligonucleotides levels (2'OMe as well as PMO) in dystrophin-deficient muscle fibers are much higher than in healthy fibers, leading to higher exon-skipping levels.26 According to Hoffman,27 the absence of dystrophin leads to membrane instability, and the affected myofibers tear holes in their cell walls, leading to an efflux of creatine kinase and an influx of calcium. DMD patients probably have a disease-specific delivery advantage, since antisense oligonucleotides might cross the myofiber membrane through the same holes through which creatine kinase leaks out. This disease-specific delivery advantage could turn into a problem when considering viral genomes during AAV-U7 treatment and participate to the viral genome loss when dystrophin rescue is not optimal.

This dark painting of AAV mediated clinical trials can be tempered by the fact that dystrophin levels as low as 30% are sufficient to avoid muscular dystrophy in humans.28 In addition, a minimal level of dystrophin partially ameliorates hind limb muscle passive mechanical properties in dystrophin-null mice.29 However, to achieve long-term restoration of dystrophin expression, one can imagine a two-step treatment with firstly, a single systemic injection of AAV-U7 vector to induce a strong and widespread expression of dystrophin in muscles, and secondly, recurrent systemic injections of antisense oligonucleotides to prevent the progressive reappearance of a dystrophic phenotype caused by the partial loss of AAV genomes over time.

Materials and Methods

Viral vector production and animal experiments. A three-plasmid transfection protocol was used with pAAV(U7smOPT-SD23/BP22) and pAAV(U7smOPT-scr) plasmids for generation of single-strand AAV1-U7ex235 and AAV1-U7scr; and scAAV-U7ex23 plasmid for self-complementary scAAV9-U7ex239. pAAV(U7smOPT-scr) plasmid contains the non specific sequence GGTGTATTGCATGATATGT that does not match to any murine cDNAs.

C57BL/6 (WT) and mdx mice were injected into the Tibialis anterior (TA) with 50 µl of AAV1-U7ex23 or AAV1-U7scr containing 1.2E+11, 3E+10 or 7.5E+09 viral genomes (vg). These animal experiments were performed at the Institute of Myology, Paris, France.

Approximately 1E+13 vg of scAAV9-U7ex23 were delivered to dKO mice at 3 weeks of age by intravenous injection in the tail vein. Treated mice were killed at 13 weeks of age or at a humane endpoint by CO2 inhalation. These animal experiments were carried out in the Biomedical Science Building, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. All experimental procedures were performed according to the guidelines and protocols approved by the Home Office. A minimum of three mice were injected per group for each experiments. At sacrifice, muscles were collected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and stored at −80 °C.

Viral genome quantification. Genomic DNA was extracted from mouse muscles using Puregene Blood kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) as described.30 Copy numbers of AAV genome and genomic DNA were measured on 100 ng of genomic DNA by absolute quantitative real-time PCR on a LightCycler480 (Roche, Meylan, France) by SYBR green method, using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Primers were used to specifically amplify the viral genome sequence (ITR-F, CTCCATCACTAGGGGTTCCT and U7-R, GCTTTGATCCTTCTCTGGTTTC) and the mouse titin gene (Titin-F, AAAACGAGCAGTGACGTGAGC and Titin-R, TTCAGTCATGCTGCTAGCGC). As reference samples, pAAV(U7smOPT-SD23/BP22) construct and a plasmid containing the titin cDNA were tenfold serially diluted (from 107 to 101 copies). AAV genome copy number was expressed as an absolute value per diploid nucleus. All genomic DNA samples were analyzed in triplicates.

RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA was isolated from mouse muscle with NucleoSpin` RNA II (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France), and reverse transcription (RT) performed on 200 ng of RNA by using the Superscript II and random primers (Life Technologies, St Aubin, France). Non-skipped and skipped dystrophin transcripts were detected by nested PCR and quantified as described.9

Western blot analysis. Protein extracts were obtained from pooled muscle sections treated with 125 mmol/l sucrose, 5 mmol/l Tris–HCl pH 6.4, 6% of XT Tricine Running Buffer (Bio-Rad), 10% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol. The samples were purified with the Compat-Able Protein Assay preparation Reagent Set (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, IL) and the total protein concentration was determined with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce). Samples were denatured at 95 °C for 5 minutes and 50 μg of protein were loaded onto Criterion XT Tris-acetate precast gel 3–8% (Bio-Rad). Dystrophin protein was detected by probing the membrane with 1:50 dilutions of NCL-DYS1 primary monoclonal antibody (Novocastra, New Castle, UK), followed by incubation with a sheep anti-mouse secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase conjugated; 1:15,000) and ECL Analysis System (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Velizy-Villacoublay, France).

Immunohistochemistry and histology. TA sections of 12 µm were cut and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was used to examine the overall muscle morphology. The cryosections were then examined for dystrophin expression using the C-terminal rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:300; Thermo Scientific Pierce) and a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody Alexa 488 (1:1,000; Life Technologies).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), the Duchenne Parent Project France (DPP) and the Association Monégasque contre les Myopathies (AMM). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Harper SQ, Hauser MA, DelloRusso C, Duan D, Crawford RW, Phelps SF, et al. Modular flexibility of dystrophin: implications for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Med. 2002;8:253–261. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goemans NM, Tulinius M, van den Akker JT, Burm BE, Ekhart PF, Heuvelmans N, et al. Systemic administration of PRO051 in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1513–1522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirak S, Arechavala-Gomeza V, Guglieri M, Feng L, Torelli S, Anthony K, et al. Exon skipping and dystrophin restoration in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy after systemic phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer treatment: an open-label, phase 2, dose-escalation study. Lancet. 2011;378:595–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60756-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun C, Suter D, Pauli C, Dunant P, Lochmüller H, Burgunder JM, et al. U7 snRNAs induce correction of mutated dystrophin pre-mRNA by exon skipping. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:557–566. doi: 10.1007/s000180300047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyenvalle A, Vulin A, Fougerousse F, Leturcq F, Kaplan JC, Garcia L, et al. Rescue of dystrophic muscle through U7 snRNA-mediated exon skipping. Science. 2004;306:1796–1799. doi: 10.1126/science.1104297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denti MA, Rosa A, D'Antona G, Sthandier O, De Angelis FG, Nicoletti C, et al. Chimeric adeno-associated virus/antisense U1 small nuclear RNA effectively rescues dystrophin synthesis and muscle function by local treatment of mdx mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:565–574. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchaouir R, Meregalli M, Farini A, D'Antona G, Belicchi M, Goyenvalle A, et al. Restoration of human dystrophin following transplantation of exon-skipping-engineered DMD patient stem cells into dystrophic mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:646–657. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyenvalle A, Wright J, Babbs A, Wilkins V, Garcia L, Davies KE. Engineering multiple U7snRNA constructs to induce single and multiexon-skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther. 2012;20:1212–1221. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyenvalle A, Babbs A, Wright J, Wilkins V, Powell D, Garcia L, et al. Rescue of severely affected dystrophin/utrophin-deficient mice through scAAV-U7snRNA-mediated exon skipping. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2559–2571. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish LT, Sleeper MM, Forbes SC, Wang B, Reynolds C, Singletary GE, et al. Long-term restoration of cardiac dystrophin expression in golden retriever muscular dystrophy following rAAV6-mediated exon skipping. Mol Ther. 2012;20:580–589. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulin A, Barthélémy I, Goyenvalle A, Thibaud JL, Beley C, Griffith G, et al. Muscle function recovery in golden retriever muscular dystrophy after AAV1-U7 exon skipping. Mol Ther. 2012;20:2120–2133. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera VM, Gao GP, Grant RL, Schnell MA, Zoltick PW, Rozamus LW, et al. Long-term pharmacologically regulated expression of erythropoietin in primates following AAV-mediated gene transfer. Blood. 2005;105:1424–1430. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penaud-Budloo M, Le Guiner C, Nowrouzi A, Toromanoff A, Chérel Y, Chenuaud P, et al. Adeno-associated virus vector genomes persist as episomal chromatin in primate muscle. J Virol. 2008;82:7875–7885. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00649-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorain S, Gross DA, Goyenvalle A, Danos O, Davoust J, Garcia L. Transient immunomodulation allows repeated injections of AAV1 and correction of muscular dystrophy in multiple muscles. Mol Ther. 2008;16:541–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deconinck AE, Rafael JA, Skinner JA, Brown SC, Potter AC, Metzinger L, et al. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady RM, Teng H, Nichol MC, Cunningham JC, Wilkinson RS, Sanes JR. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couteaux R, Mira JC, d'Albis A. Regeneration of muscles after cardiotoxin injury. I. Cytological aspects. Biol Cell. 1988;62:171–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli M, Poupiot J, Goyenvalle A, Perez N, Garcia L, Danos O, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of therapeutic gene transfer in animal models of muscular dystrophies. Gene Ther. 2006;13:20–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumonceaux J, Marie S, Beley C, Trollet C, Vignaud A, Ferry A, et al. Combination of myostatin pathway interference and dystrophin rescue enhances tetanic and specific force in dystrophic mdx mice. Mol Ther. 2010;18:881–887. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacak CA, Conlon T, Mah CS, Byrne BJ. Relative persistence of AAV serotype 1 vector genomes in dystrophic muscle. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2008;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Minami E, Blankinship MJ, Haraguchi M, Meuse L, et al. rAAV6-microdystrophin preserves muscle function and extends lifespan in severely dystrophic mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:787–789. doi: 10.1038/nm1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabb SA, Wells DJ, Serpente P, Dickson G. Adeno-associated virus vector gene transfer and sarcolemmal expression of a 144 kDa micro-dystrophin effectively restores the dystrophin-associated protein complex and inhibits myofibre degeneration in nude/mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:733–741. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.7.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Li J, Xiao X. Adeno-associated virus vector carrying human minidystrophin genes effectively ameliorates muscular dystrophy in mdx mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13714–13719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240335297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JR, Campbell K, Rodino-Klapac L, Sahenk Z, Shilling C, Lewis S, et al. Dystrophin immunity in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1429–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Storb R, Halbert CL, Banks GB, Butts TM, Finn EE, et al. Successful regional delivery and long-term expression of a dystrophin gene in canine muscular dystrophy: a preclinical model for human therapies. Mol Ther. 2012;20:1501–1507. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk H, de Winter C, van Kuik P, Heuvelmans N, Sabatelli P, Rimessi P, et al. Preclinical PK and PD studies on 2'-O-methyl-phosphorothioate RNA antisense oligonucleotides in the mdx mouse model. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1210–1217. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman EP. Skipping toward personalized molecular medicine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2719–2722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0707795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri M, Torelli S, Brown S, Ugo I, Sabatelli P, Merlini L, et al. Dystrophin levels as low as 30% are sufficient to avoid muscular dystrophy in the human. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17:913–918. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim CH, Duan D. A marginal level of dystrophin partially ameliorates hindlimb muscle passive mechanical properties in dystrophin-null mice. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46:948–950. doi: 10.1002/mus.23536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guiner C, Moullier P, Arruda VR. Biodistribution and shedding of AAV vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;807:339–359. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]