Abstract

Background & objectives:

Regular practice of slow breathing has been shown to improve cardiovascular and respiratory functions and to decrease the effects of stress. This pilot study was planned to evaluate the short term effects of pranayama on cardiovascular functions, pulmonary functions and galvanic skin resistance (GSR) which mirrors sympathetic tone, and to evaluate the changes that appear within a short span of one week following slow breathing techniques.

Methods:

Eleven normal healthy volunteers were randomized into Pranayama group (n=6) and a non-Pranayama control group (n=5); the pranayama volunteers were trained in pranayama, the technique being Anuloma-Viloma pranayama with Kumbhak. All the 11 volunteers were made to sit in similar environment for two sessions of 20 min each for seven days, while the pranayama volunteers performed slow breathing under supervision, the control group relaxed without conscious control on breathing. Pulse, GSR, blood pressure (BP) and pulmonary function tests (PFT) were measured before and after the 7-day programme in all the volunteers.

Results:

While no significant changes were observed in BP and PFT, an overall reduction in pulse rate was observed in all the eleven volunteers; this reduction might have resulted from the relaxation and the environment. Statistically significant changes were observed in the Pranayama group volunteers in the GSR values during standing phases indicating that regular practice of Pranayama causes a reduction in the sympathetic tone within a period as short as 7 days.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Beneficial effects of pranayama started appearing within a week of regular practice, and the first change appeared to be a reduction in sympathetic tone.

Keywords: Galvanic skin resistance, Pranayama, sympathetic tone

Pranayama, meaning ‘breath control’, is an ancient technique involving slow and rhythmic breathing. It is known that the regular practice of pranayama increases parasympathetic tone, decreases sympathetic activity, improves cardiovascular and respiratory functions, decreases the effect of stress and strain on the body and improves physical and mental health1,2,3,4. Regular practice of rhythmic slow breathing has been shown to increase baroreflex sensitivity and reduce chemoreflex activation5, and to reduce systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressures as well as heart rate variations in hypertensive patients6. Practice of slow breathing has also been advocated for the treatment of anxiety disorders as it attenuates cardiac autonomic responses in such patients7.

It has been reported in one study that a single 10-minute session of slow breathing caused a temporary fall in blood pressure, heart rate, electromyograph (EMG) activity, and a rise in skin temperature8. Another study showed that slow breathing over a span of 4 wk increased parasympathetic activity9. A couple of studies observed that regular practice of slow breathing exercise for a minimum of three months improved autonomic functions10,11. Thus, there is lack of consensus regarding the latency of onset of the beneficial effects of pranayama. Hence, this pilot study was designed to evaluate the short term effects of slow breathing exercise on various cardiovascular functions, pulmonary functions and galvanic skin resistance (GSR) which mirrors sympathetic tone, and to evaluate how early does it take for the changes to appear because of slow breathing techniques, in normal healthy volunteers.

Material & Methods

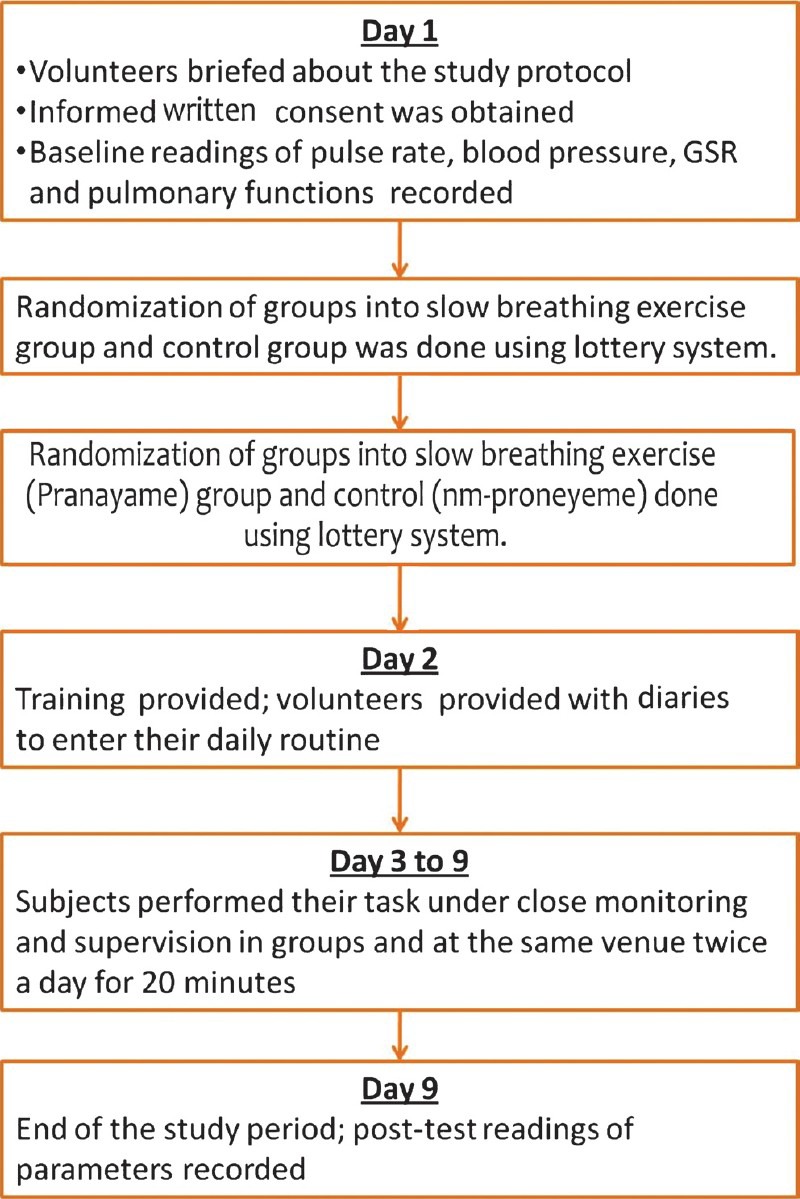

The study was conducted over eight days during August 2009 in the Department of Pharmacology, Grant Medical College, Mumbai, India, on 11 healthy males aged between 18-30 yr. Participants were randomly selected from amongst the teaching staff and postgraduate residents from the department of pharmacology. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee and informed written consent was taken from all the participants. Volunteers outside the body mass index (BMI) range of 18.5 and 25 kg/m2, smokers, alcoholics, suffering from any chronic disease condition, on medication for any condition or following any type of exercise regimes including pranayama and non-consenting individuals were excluded from the study. The volunteers were asked to follow the exercise schedule regularly, be on a uniform, balanced, vegetarian diet throughout the study period, wear lose and comfortable clothes and to avoid tea/coffee 1 h before and food 2 h before the exercise. The entire activity was executed under the proper guidance of an expert who gave the training for the breathing maneuvers. The study methodology is summarized in the Figure.

Fig.

Flow diagram showing the study methodology.

The 11 subjects were randomly assigned to perform either the slow breathing exercise (Pranayama group, n=6) or regular breathing (non-pranayama group, n=5). All were asked to sit in the same environment, once in the morning and once in the evening for 20 min each.

Slow breathing was done by sitting on the ground in Sukhasana (crossed leg with cervical and lumbar spine extended, arms pronated and extended, wrists placed on knees, and fist closed), in an ambient, well-ventilated, quiet room, at room temperature; it was ensured that the subjects had no nasal obstruction. The subjects of the Pranayama group were trained in the Anuloma-Viloma technique of pranayama with Kumbhak (alternative nostril breathing with breath holding). The subjects were asked to breathe in through the left nostril over a period of 6 sec, hold their breath for 6 sec with both nostrils closed, and then to exhale through the right nostril over a period of 6 sec. This constituted one breathing cycle, and the subjects performed about 30 such cycles once in the morning and in the evening12.

The subjects of the non-pranayama group performed regular rhythmic breathing in a sitting posture same as those of the Pranayama group volunteers without any conscious control of respiratory rate and depth.

Recording of body functions: The body functions recorded included pulse rate, galvanic skin resistance (GSR), blood pressure (BP) and pulmonary function tests (PFT). All recordings were done in a quiet room at ambient room temperature. The person who recorded the body functions was blinded for randomization.

The recordings for pulse rate and GSR were made using an 8-channeled polygraph (Medicaid systems, Chandigarh). The subjects were asked to lie down, stand up, again lie down, perform a stepping exercise (the volunteers were asked to step up and down a wooden block 20 cm tall, and complete at least 30 such cycles in one minute), and again lie down, each stage lasting for one minute. The pulse and GSR were recorded during these five stages. The sensors of the GSR electrodes were placed on the pulp of index and middle finger of the right hand, and those of the pulse electrodes were placed on the pulp of the right index finger. The mid phase (reading at 30 sec) pulse rate and amplitude of GSR were noted.

The blood pressure was recorded using an automatic BP measuring apparatus (Omron, India) with the cuff tied to the right arm. The systolic and diastolic BP (SBP and DBP) were noted down at the end of all stages and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated using the formula MAP=[SBP* (1/3) + DBP* (2/3)]. Pulmonary functions were recorded in standing posture using polygraph. The forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1) were noted.

The post-test recording of the parameters was done after one hour of the last pranayama session after allowing for the normal bodily functions to return to baseline.

Statistical analysis: Changes in values of pulse rate, GSR, MAP and PFT due to various phases of exercise with respect to baseline recordings were calculated and compared within each group. The change of parameters between resting (phase 1) and standing (phase 2), and between resting (phase 3) and stepping exercise (phase 4) were also compared both within the group and between the groups. The within-group analysis was done by paired ‘t’ test, inter-group analysis was done by unpaired ‘t’ test.

Results

In both the groups, age and BMI of all subjects were comparable. In the Pranayama group, the mean age was 27.83 ± 0.91 yr and mean BMI was 23.58 ± 0.74 kg/m2. In non-pranayama group, the mean age was 28.80 ± 2.15 yr and mean BMI was 24.95 ± 1.23 kg/m2.

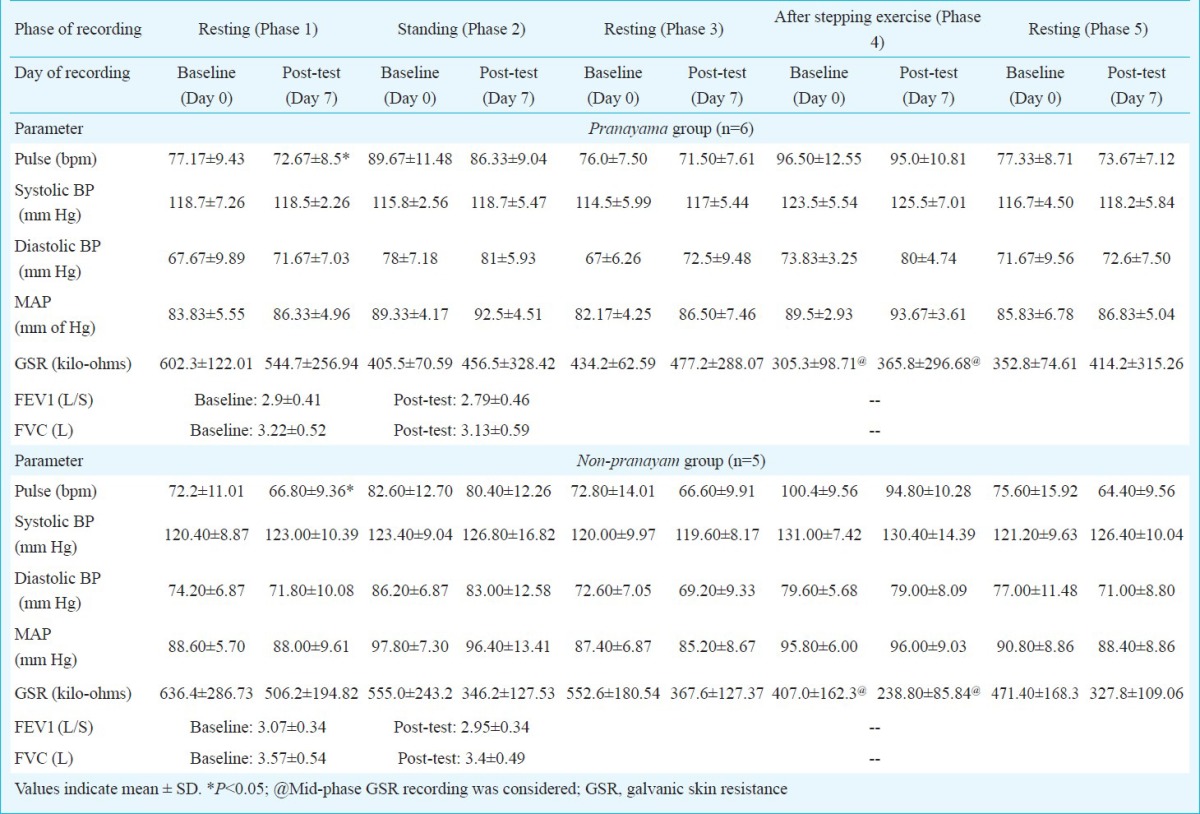

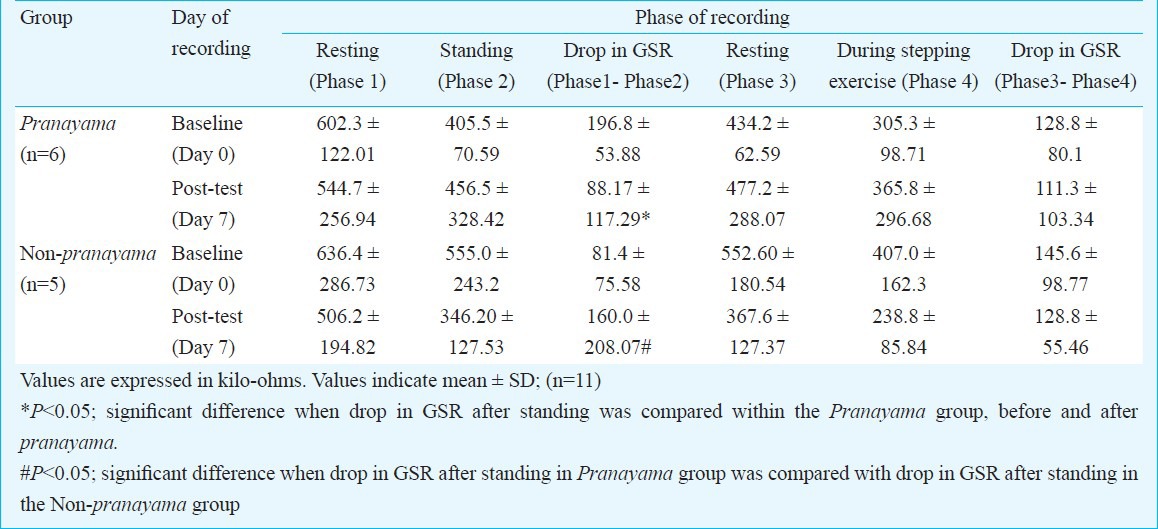

In the Pranayama group, though there was a general fall in pulse rate in all the five phases of recording, a significant drop was only seen in the resting pulse at the end of the study. There were no statistically significant changes in SBP, DBP and MAP in any of the phases. The GSR in the resting phase was decreased in the post-study recording; there was a rise in GSR in the other phases; none of the changes were significant (Table I). There was a significant decrease in ‘drop in GSR’ after standing; the reduction in ‘drop in GSR’ after stepping exercise was not significant (Table II). There was no significant change in FEV1 and FVC (Table I).

Table I.

Effect of pranayama and non-pranayama on pulse, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure and pulmonary function test (MAP) and (PFT)

Table II.

Effects on galvanic skin resistance (GSR) in pranayama and non-pranayama groups

In the non-pranayama group, while there was a general fall in pulse rate in all the five phases of recording, a significant drop was only seen in the resting pulse after the study period. There was no significant change in SBP, DBP and MAP in any of the phases. There was a non-significant general fall in GSR in all the phases during the post-study recording (Table I). The ‘drop in GSR’ was increased after standing but decreased after stepping exercise (Table II).

There was no significant difference between the two groups with regards to the baseline readings, pulse rate during resting, standing and stepping exercise phases, and other parameters. The changes during standing phase in GSR were significant in favour of slow breathing exercise group rather than the non pranayama group.

Discussion

A significant drop was observed in resting pulse rate in both groups following the week-long relaxation practice whether or not involving pranayama. This may be because of the similar body posture adopted by the subjects and the same peaceful environment to which both the groups were exposed. Apart from the breathing exercise there was no other condition which differentiated both the groups. There was no significant change in SBP, DBP or MAP in either of the groups. All subjects in our study were normotensives. The reason for this might be twofold: one all the subjects in the study were normotensives, and two, the short period of study, i.e. 7 days. A previous study demonstrated a temporary fall in blood pressure following a ten minute session of slow breathing and mental relaxation but the study was performed on hypertensives8. Another study also performed on hypertensive individuals6, reported a fall in blood pressure following slow breathing exercise. Other studies on healthy normotensive volunteers which reported a fall in blood pressure were conducted for a duration of 4 wk and above1,9. Another study4 reported a fall in blood pressure after 5 min of pranayama; however, the procedure of slow breathing exercise was different from the procedure followed in our study.

GSR is the electrical resistance recorded between two electrodes placed on the hand with a feeble electric current running between them. A change in autonomic tone, largely sympathetic, results in alteration of GSR. For example, following sympathetic stimulation, there is a slight increase in sweating, and this slight increase is enough to lower the skin resistance since the sweat contains water and electrolytes, both of which increase the conductivity of skin. Thus a fall in GSR indicates a rise in sympathetic tone. A significant increase was observed in the GSR reading on standing in the pranayama group; this was not seen with the non-pranayama group. It indicates a decrease in the sympathetic tone while performing routine daily activities. The fact that this change was observed following the practice of pranayama for a short span of 7 days suggests that a decrease in sympathetic tone might be the earliest change amongst the various physiological changes seen following a regular practice of pranayama. No such change was seen in the non-pranayama group. This difference in GSR between the two groups seen during standing phase was significant, thus indicating the early-onset benefits of pranayama.

Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain this decrease in sympathetic tone, and the associated increase in parasympathetic tone following pranayama. These include an increase in vagal tone following the slow breathing exercise1,10, an increase in baroreflex sensitivity5, an increase in tissue oxygenation10, and interaction of pranayamic breathing with the nervous system affecting metabolism and autonomic functions13.

To conclude, this pilot study showed that the practice of slow breathing exercise (pranayama) on a regular basis attenuated the sympathetic tone of body in healthy volunteers, and that the changes began to appear in a short period of seven days, the changes in GSR observed at the earliest. Further studies on a large number of individuals for a long duration are required to confirm the findings.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Dr M.M. Jain, Associate professor and in-charge of Clinical Pharmacology Unit, GMC and Sir JJ Group of Hospitals, Mumbai for his co-operation and Dr Ashwini Pawar for being the time manager for the events of pranayam.

References

- 1.Bhargava R, Gogate MG, Mascarenhas JF. Autonomic responses to breath holding and its variations following pranayama. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1988;42:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telles S, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. Breathing through a particular nostril can alter metabolism and autonomic activities. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;38:133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohan M, Saravanane C, Surange SG, Thombre DP, Chakrabarty AS. Effect of yoga type breathing on heart rate and cardiac axis of normal subjects. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1986;30:334–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pramanik T, Sharma HO, Mishra S, Mishra A, Prajapati R, Singh S. Immediate effect of slow pace bhastrika pranayama on blood pressure and heart rate. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:293–5. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph CN, Porta C, Casucci G, Casiraghi N, Maffeis M, Rossi M, et al. Slow breathing improves arterial baroreflex sensitivity and decreases blood pressure in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:714–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000179581.68566.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinheiro CH, Medeiros RA, Pinheiro DG, Marinho Mde J. Spontaneous respiratory modulation improves cardiovascular control in essential hypertension. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;88:651–9. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakakibara M, Hayano J. Effect of slowed respiration on cardiac parasympathetic response to threat. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:32–7. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaushik RM, Kaushik R, Mahajan SK, Rajesh V. Effects of mental relaxation and slow breathing in essential hypertension. Complement Ther Med. 2006;14:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upadhyay Dhungel K, Malhotra V, Sarkar D, Prajapati R. Effect of alternate nostril breathing exercise on cardiorespiratory functions. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10:25–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal GK, Velkumary S, Madanmohan Effect of short term practice of breathing exercises on autonomic functions in normal human volunteers. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:115–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udupa K, Madanmohan, Bhavanani AB, Vijayalakshmi P, Krishnamurthy N. Effect of pranayam training on cardiac function in normal young volunteers. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breathing exercise (Pranayama) - alternate nostril (Anuloma Viloma) 2007. [accessed on December 1, 2011]. Available from: http://www.abc-of-yoga.com/pranayama/basic/viloma.asp .

- 13.Jerath R, Edry JW, Barnes VA, Jerath VS. Physiology of long pranayamic breathing; neural respiratory elements, may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]