Abstract

Four randomized phase III trials conducted recently in melanoma patients in the adjuvant setting have been based in part on the correlation between antibody responses in immunized patients and improved survival. Each of these randomized trials demonstrated no clinical benefit, although again there was a significant correlation between antibody response after vaccination and disease free and overall survival. To better understand this paradox, we established a surgical adjuvant model targeting GD2 ganglioside on EL4 lymphoma cells injected into the foot pad followed by amputation at variable intervals. Our findings are (1) comparable strong therapeutic benefit resulted from treatment of mice after amputation with a GD2-KLH conjugate vaccine or with anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody 3F8. (2) The strongest correlation was between antibody induction in response to vaccination and prolonged survival. (3) Antibody titers in response to vaccination in tumor challenged mice as compared to unchallenged mice were far lower despite the absence of detectable recurrences at the time. (4) The half life of administered 3F8 monoclonal antibody (but not control antibody) in challenged mice administered was significantly shorter than the half life of 3F8 antibody in unchallenged controls. The correlation between vaccine-induced antibody titers and prolonged survival may reflect, at least in part, increased tumor burden in antibody-negative mice. Absorption of vaccine-induced antibodies by increased, although not detected tumor burden may also explain the correlation between vaccine-induced antibody titers and survival in the adjuvant clinical trials described above.

Keywords: GD2 ganglioside, GD2-KLH conjugate, mAb, 3F8, EL4, Cancer vaccines

Introduction

Antibodies are the primary mechanism for active elimination of circulating and early invasive pathogens from the bloodstream and tissues. They are ideally suited for eradication of free tumor cells and systemic or intraperitoneal micrometastases and they have accomplished this in a variety of preclinical studies [2–8]. In humans, human monoclonal antibodies against cell surface antigens on lymphomas and solid tumors, such as CD20, CD33 and CD52, and HER2/neu, epidermal growth factor receptor and VEGF have shown significant antitumor efficacy. At least in the case of trastuzumab, a human mAb against the HER2/neu antigen, this was especially significant in the post-surgical, adjuvant setting [9]. Vaccine-induced antibodies in cancer patients against a variety of tumor antigens have been shown to correlate with improved disease free and overall survival [10–17]. Four of these were related to randomized trials performed in melanoma patients testing a GM2 ganglioside vaccine or a whole cell melanoma vaccine targeting gangliosides and a variety of other antigens. In each case, despite the clear correlation between antibody response against targeted antigens and survival, there was no clinical benefit from vaccination when the vaccine and placebo or no treatment arms of the trial were compared [18–21]. The experiments described below were designed to address this paradox.

Gangliosides have been uniquely effective targets for both active and passive antibody therapies [5, 7, 8, 22, 23]. GD2 is a disialoganglioside expressed on tumors of neuroectodermal origin, including neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma and to a lesser extent, malignant melanoma [24], J and monoclonal antibodies (mAb) 3F8 and CH14.18 recognizing GD2 have been extensively used to treat children with neuroblastoma [22, 23, 25]. Several preclinical models have addressed the role of immunization with GD2 or peptide mimics of GD2 (GD2 mimotopes) in protection from tumor challenge [26–28]. In our experience, the optimal way to induce antibodies against gangliosides, such as GD2 has been to conjugate the ganglioside to KLH and use a potent saponin immunological adjuvant such as QS-21 [10, 29]. We have described a syngeneic preclinical model for studying the impact of GD2 antibodies in the minimal disease setting [8]. 3F8 administered 2 or 4 days after intravenous challenge with syngeneic EL4 murine lymphoma cells (which naturally express GD2) was able to eradicate disease in most mice. Immunization with a vaccine containing GD2 covalently conjugated to KLH (GD2-KLH) plus QS-21 [30] results in induction of antibodies against GD2 in most mice [8] and protection from challenge when the vaccinations are started before challenge or immediately after challenge. More delayed administration of either 3F8 or GD2-KLH vaccine resulted in minimal or no protection. These studies have all demonstrated that when antibodies of sufficient titer can be induced or administered, residual circulating tumor cells or micrometastases can be eliminated and tumor recurrence prevented. The antibody effector mechanisms in this EL4 model have been explored utilizing IgG (3F8) and IgM mAbs against GD2. Antibody mediated protection involves both complement independent and complement-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), mediated primarily by IgG and IgM antibodies, respectively [31].

Although these intravenous or subcutaneous challenge models demonstrated the ability of antibodies to eliminate circulating tumor cells and micrometastasis, they had limitations as adjuvant models for improving antibody-based approaches to therapy of human cancers and for exploring the dichotomy between the clear correlation of vaccine-induced antibody titers to prolonged patient survival and the lack of benefit of these same vaccines in randomized clinical trials [18, 19]. In particular, the 2–4-day window of opportunity after intravenous tumor challenge is hard to extrapolate to adjuvant therapy in the clinic. We demonstrate here a more clinically relevant post-surgical adjuvant model for the prevention of regrowth of EL4 cells and use this model to explore the correlation between vaccine-induced antibody levels, tumor burden and survival [25].

Materials and methods

Mice and cell lines

C57BL/6J mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The EL4 cell line was established from lymphoma induced in a C57BL/6J mouse by 9,10-dimethyl-1,2-benzanthracene [33] and has been shown to express GD2 [34]. EL4 was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS.

Monoclonal antibodies and vaccine

The origin of mAb 3F8 (IgG3) against GD2 has been described [22]. It was purified by protein A affinity chromatography. Immunological adjuvant QS-21, a purified saponin fraction [30], was obtained from Aquila Biopharmaceuticals Inc. (now Antigenics Inc., NYC, NY). Midway through these studies, QS-21 was no longer available for our use. The semi-synthetic saponin adjuvant, GPI-0100, was substituted based on our previous study demonstrating that GPI-0100 was at least as potent an adjuvant as QS-21 [35]. GD2 was prepared from bovine GD1b by treatment with β-galactosidase [36] and provided by Progenics Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Tarrytown, NY). It was conjugated to KLH as previously described [32]. The conjugated ratio of GD2/KLH was 951/1. Before vaccination, GD2-KLH in saline was mixed with QS21 or GPI-0100 in a total volume of 0.1 ml. Each dose of GD2-KLH vaccine contained 5 μg GD2, 60 μg KLH and 10 μg QS-21 or 200 μg GPI-0100. Vaccines and KLH plus QS-21 control were administered s.c. 3–4 times at 3 to 7-day intervals, as we have published previously [8]. Titers are comparable with these different vaccination intervals, but occur earlier with the shorter intervals.

Protection experiment

EL4 cell GD2 expression was confirmed using flow cytometry with mAb 3F8. EL4 cells were washed three times in PBS and 5 × 105 cells were injected into the footpad. When increase in footpad thickness exceeded 0.9 mm in the majority of mice (generally days 24–30), amputation was performed below the knee joint using a Surgicare fine tip cautery unit (American White Cross, Dayville, CT). Before amputation, ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) were administered i.p. for general anesthesia. After amputation, local anesthesia 25% bupivacaine was applied and the wound was sutured with vicryl absorbable suture (Ethicon, Sommervile, NJ). To prevent shock and help recovery in anesthetized mice, 1 ml physiologic saline was injected subcutaneously or intraperitoneally after operation. After challenge foot pads were amputated on day 24 or 31. Groups of mice amputated on day 24 were treated with 5µg GD2-KLH plus QS-21 or KLH plus QS-21 or PBS alone on days 25, 29, 33 and 37, or with 100 µg of mAb 3F8 on days 31 and 38. Groups of mice amputated on day 31 were treated with 5 µg GD2-KLH plus QS-21 or KLH plus QS-21 or PBS alone on days 32, 36, 40 and 44, or 100 µg of mAb 3F8 on days 32 and 39 or on days 38 and 45. Experimental groups were compared with controls for the number of hepatic metastases and survival by one-way analysis of variance. To confirm tumor-free status, autopsies were performed in long-term survivors.

Serological assays

ELISA assays were performed to determine IgM and IgG serum antibody titers against GD2 as previously described [8]. In brief, 0.1 μg GD2 per well in ethanol was coated on ELISA plates overnight at room temperature. Nonspecific sites were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in saline for 2 h. Serially diluted antiserum was added to each well. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were washed and alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgM or IgG was added at 1:200 dilution. The antibody titer was defined as the highest dilution with absorbance of 0.1 or greater over that of control mouse sera. Pretreatment sera were consistently negative (absorbance <0.1 at a dilution of 1/5). Post-vaccination sera with titers >1/20 were considered positive.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival was defined as the time from footpad challenge to date of death or day 80. Survival distributions were generated using Kaplan–Meier methodology and comparisons between treatment group and control (PBS and KLH plus QS21) were made via the log-rank test for groups of 15 or fewer mice and the χ2 test for larger groups.

Results

Effect of mAb administration or vaccination on survival

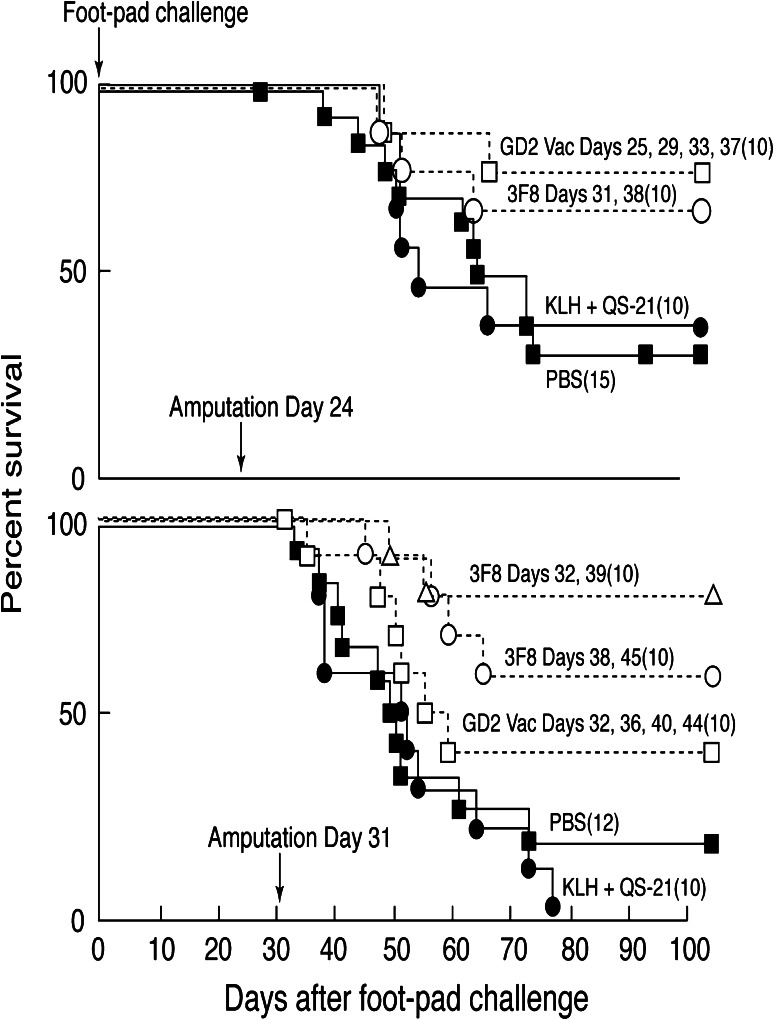

The ability of adoptively administered mAb 3F8 and of GD2-KLH plus QS21 vaccine induced antibodies (generally detectable 6–10 days after initial immunization) to prevent tumor recurrence in this post-surgical model was determined. In five separate consecutive experiments (10–15 mice per group) mAb and/or vaccine treatments administered after amputation (when there was no visible or palpable tumor) significantly prolonged survival when compared with the relevant controls (p values between ≤ 0.08 and ≤ 0.001). Figure 1 demonstrates the results of experiments performed with amputation at two relatively late intervals as examples. Amputation when footpad tumors measured about 1 mm (day 24 in this experiment) resulted in cure of 35% of mice in the control groups (PBS or KLH plus QS21). Therapy with mAb 3F8 beginning on day 31 or with vaccine beginning on day 25 resulted in significantly prolonged survival (p < 0.04 and p < 0.01, respectively) and 70–80% of mice were free of detectable tumor at killing on day 80. Delaying amputation until footpad tumor measured 2–3 mm (day 31 in this experiment) resulted in cure of 0–10% of control mice, 80% of mice treated with 3F8 beginning day 32 (p < 0.001), and 60% of mice treated with 3F8 beginning on day 38 (p < 0.01). Vaccination with GD2-KLH plus QS21 beginning day 32 resulted in detectable antibodies by day 42 and cure of 40% of mice (p < 0.08).

Fig. 1.

Survival of groups of 10–15 C57BL/6 mice (numbers indicated in parenthesis) challenged with 5 × 105 EL4 cells by footpad injection on day 0, all tumor removed by amputation on days 24 or 31 and treated with 100 μg 3F8 mAb, 5 μg GD2-KLH plus 10 μg QS-21 vaccine, or various control treatments. Survival in treated mice when compared with survival in PBS and KLH + QS-21 controls (pooled) was determined using Kaplan–Meier methodology and are indicated. Amputation day 24: 3F8 p < 0.04, GD2-KLH p < 0.01. Amputation day 31: 3F8 day 32 p < 0.001, 3F8 day 38 p < 0.01, GD2-KLH p < 0.08

Correlation between vaccine-induced antibody titer and protection

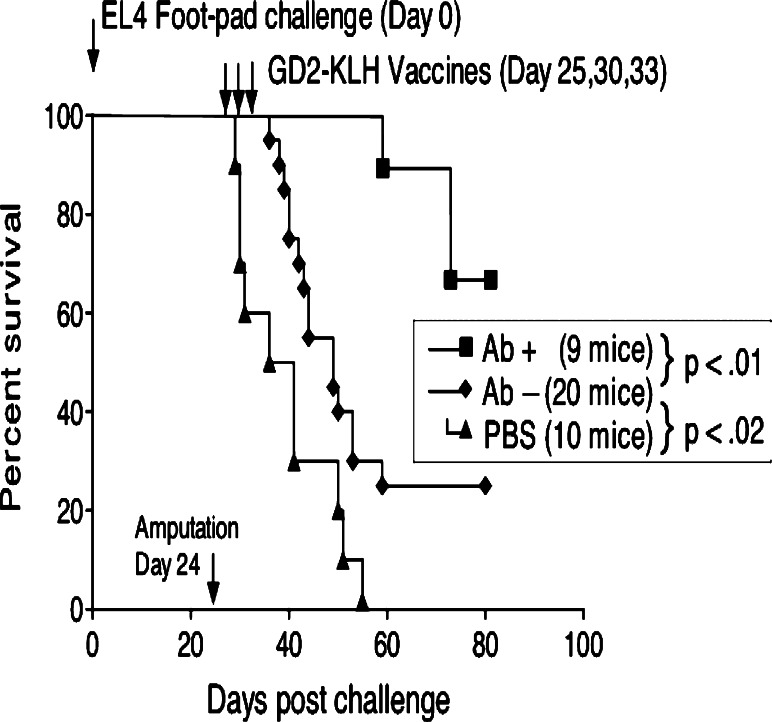

Mice receiving the GD2-KLH vaccine after footpad challenge and amputation in these experiments consistently survive longer as described above. There was an even more significant correlation between antibody titer (predominantly IgM) and survival. Mice with detectable anti-GD2 antibodies (titer >1/20 by ELISA) after challenge and vaccination have prolonged survival, generally remaining tumor-free (p values compared with antibody-negative vaccinated mice range between 0.001 and 0.0001 in the 5 experiments). The results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 2. Challenged and vaccinated mice that developed no detectable antibodies are also protected when compared with mice not vaccinated, but to a lesser degree (p values 0.2–0.01 in 5 experiments).

Fig. 2.

Survival of 9 IgM antibody-positive and 20 antibody-negative C57BL/6 mice after vaccination with GD2-KLH plus GPI-0100 when compared with 10 unvaccinated mice. Amputation was day 24, after the 5 × 105 EL4 cell footpad challenge, vaccinations were on days 25, 30 and 33, and mice were bled for antibody titers on day 38. Both antibody-positive and antibody-negative vaccinated mice were significantly protected when compared with PBS-treated control mice (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.02, respectively)

Impact of tumor challenge on antibody titers

It was noticed in all of these experiments that vaccine induced GD2 antibody titers, but not KLH antibody titers (data not shown) in tumor challenged mice were significantly lower than we had seen previously in vaccinated mice that had not been challenged. To summarize, of 25 unchallenged mice receiving 3 vaccinations, 23 made GD2 antibody responses >1/20 with a median titer of 1/160. On the other hand, of 70 mice challenged day 0 in the foot pad with EL4, amputated days 20–24 and then immunized with the same vaccine and regimen, 24 made detectable GD2 antibodies with a median titer of 1/40 (comparison of results in 25 unchallenged mice with results in 70 challenged mice, p < 0.0001). To determine whether this decreased antibody response to vaccination could be due to adsorption of GD2 antibodies by undetectable micrometastases, groups of mice were treated in three experiments with 3F8 mAb after footpad challenge (5 × 105 EL4 cells) when footpad tumors measured 0.8–3.3 mm., or as in the forth experiment immediately after footpad (and tumor) amputation. Sera were drawn at intervals after 3F8 administration. Anti-GD2 titers were compared with titers in sera drawn after 3F8 administration to unchallenged control mice in the same experiments (see Table 1). No anti-GD2 reactivity was detectable by days 7–14 in mice with footpad tumor and/or post-amputation micrometastases, while in control mice high titers persisted to at least days 14–21. To further demonstrate the specificity of this shortened circulating half life, mAb R24 which is also an IgG3 murine mAb and is specific for GD3 (not expressed on EL4 cells) was injected. MAb R24 titers persisted in both tumor challenged and unchallenged groups equally. Finally, 200 µg of the IgM murine monoclonal antibody against GD2, 3G6, was injected to mice 7 days after footpad challenge with 2 × 106 EL4 cells or to unchallenged mice and antibody titers determined. In both the groups, the half life of circulating antibody was diminished, as expected for IgM antibodies, but once again the fall off was significantly more rapid in the challenged mice that had a 1-mm footpad tumor at the time of antibody administration.

Table 1.

Median serum anti-GD2 antibody titers after treatment with 3F8 mAb in groups of EL4 challenged or normal mice

| mAb administered | EL4 footpad challenge | ELISA target | ELISA median titer after administration of 100 mg 3F8* | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | Class | No. of mice | Day | Number of cells | Ft pad increase: day 0 | Days 1–2 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | ||||

| 100 µg 3F8 | IgG | 31 | −14 to −25 | 5 × 105 | 1–3 mm | GD2 | 1/2,400 | 1/320 | p < 0.005* | 0 | p < 0.005 | 0 | p < 0.02 |

| 100 µg 3F8 | IgG | 24 | None | None | GD2 | 1/9,600 | 1/4,600 | 1/640 | 1/20 | ||||

| 200 µg 3F8 + 200 µg R24 | IgG | 4 | 22** | 5 × 105 | 1 mm** | GD2 | 1/1,280 | 1/160 | p = 0.025 | 0 | p = 0.05 | 0 | |

| GD3 | 1/800 | 1/300 | 1/50 | 0 | |||||||||

| IgG | 4 | None | None | GD2 | 1/5,120 | 1/960 | 1/80 | 0 | |||||

| GD3 | 1/800 | 1/200 | 1/50 | 0 | |||||||||

| 200 µg 3g6 | IgM | 5 | −7 | 2 × 106 | 1 mm | GD2 | 1/320 | 0 | p < 0.025 | 0 | p < 0.025 | 0 | |

| 200 µg 3G6 | IgM | 5 | None | None | GD2 | 1/1,280 | 1/20 | 0 | 0 | ||||

* p values derived by comparing antibody titers for the challenged mice to the unchallenged (none) mice using the log ranks test

** Amputation performed day- 21, before 3F8 administration

Discussion

We demonstrate here that treatment with anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody 3F8 or vaccination with GD2-KLH after delayed amputation results in cure of 30–80% of mice destined to develop metastatic disease after footpad challenge depending on the interval between amputation and treatment. Vaccination with GD2-KLH or treatment with 3F8 mAb are shown to be equally effective except for a 6–10 day delay after initiating vaccination, the time required before serum antibodies are detectable. Interestingly, although vaccination with GD2-KLH had clear therapeutic benefit, the vaccine-induced GD2 antibody titers (but not KLH antibody titers) following EL4 challenge were strikingly less frequent and lower than the consistently high titers induced with the same vaccine in the absence of previous EL4 challenge. Our assumption was that reduced antibody titers against GD2 resulted from increased immunological tolerance to GD2 following exposure to GD2-rich EL4 cells. To rule out the possibility that growing but not yet palpable metastatic lesions may adsorb protective antibodies, we compared the duration of detectable 3F8 antibody titer in the sera of unchallenged mice and mice with small growing tumors or undetectable micrometastases after amputation. Surprisingly, antibody titers at 2–14 days after administration of IgG mAb 3F8, but not mAb R24 targeting GD3 which is not expressed on EL4, and of IgM mAb 3G6 (also targeting GD2) were significantly reduced by the presence of 1–3-mm footpad tumors or undetectable micrometastases after amputation. The clearly diminished half life of serum mAb 3F8 and 3G6 in mice with small footpad tumors or micrometastatic disease indicates that adsorption of antibody on not yet detectable metastases is at least part of the explanation for the diminished antibody titers in EL4 challenged and vaccinated mice.

Despite the lower titer of antibodies induced in vaccinated mice that had been injected with EL4 cells, there was a striking correlation between vaccine-induced antibody titers after vaccination in these mice and protection from tumor regrowth and death. The adsorption of antibody by undetected metastases described above may at least partially explain the correlation between antibody titers in vaccinated mice and survival. Mice with micrometastases that were larger and so no longer curable by the antibodies, although still undetectable, may have had less circulating antibody due to adsorption by tumor cells. The protection seen in vaccinated mice with no detectable antibody is harder to explain. It is likely that even low (undetectable by our assays) levels of vaccine-induced GD2 antibodies and the consequent complement activation and antibody-dependent cell-mediated effector mechanisms were sufficient for protection or to set in motion other protective mechanisms.

We utilized here a syngeneic EL4 tumor challenge model that imitates the post-surgical adjuvant setting in the clinic. In this model, we found that footpad challenge with 2 × 105 or more EL4 cells results in local growth, systemic metastasis and death in over 90% of mice. Early amputation (resection of all known disease) is curative. With amputation delay until footpad thickness was increased by 1 mm or 2–3 mm, disease progressed in 65 or 95% of mice, respectively. This outcome imitates the adjuvant setting in the melanoma clinic after lymph node dissections in which 1, 3–4, or more than 5 positive lymph nodes were detected. This model has the advantage (like adjuvant treatment in patients) that it addresses the role of vaccination in preventing outgrowth of metastatic micrometastases. Unlike our experience with resecting subcutaneous or mammary fat pad tumor challenges which frequently recurred locally, local regrowth of tumor at the amputation site when the footpad measured <3 mm was rare.

The findings generated using this tumor challenge model have prognostic and therapeutic implications. Prognostically, in the clinical adjuvant setting, antibody titers after vaccination against a variety of antigens have been shown to correlate with improved survival [10–17] suggesting that the antibodies were responsible for the improved prognosis in these patients. The lack of clinical benefit in randomized trials [18–22] with some of these same vaccines plus the findings presented here suggest an alternative explanation. Our findings suggest that in a setting, where most or all patients are expected to generate a detectable post-vaccination antibody response against one or more cancer antigens, failure to mount a detectable antibody response may be a marker for early disease progression. Therapeutically, administered or induced antibodies against GD2 are able to improve survival. However, our findings with this model also emphasize that to maximize this improvement, antibody-inducing vaccines and mAbs should be administered not only to patients in the adjuvant setting but also to adjuvant patients with the lowest tumor burdens or perhaps administered in combination with chemotherapy or other adjuvant treatments to further reduce tumor burden.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant PO1 CA33049 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Koodish Family Charitable Lead Trust. Dr. Livingston and Dr. Ragupathi are paid consultants and share holders in MabVax Therapeutics Inc. who has licensed the GD2-KLH vaccine from MSKCC.

Abbreviations

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- ADCC

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- CDC

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FCS

Fetal calf serum

- NK cells

Natural killer cells

- IV

Intravenous

- KLH

Keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- sTn

Sialyl Tn

Footnotes

The designations GM2, GD2 and GD3 are used in accordance with the abbreviated ganglioside nomenclature of Svennerholm [1].

References

- 1.Svennerholm L. Chromatographic separation of human brain gangliosides. J Neurochem. 1963;10:613–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1963.tb08933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenthal A, Lafreniere R, Lefor AT, Rosenberg SA. Effect of anti-B16 melanoma monoclonal antibody on established murine B16 melanoma liver metastases. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2771–2776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hara I, Takechi Y, Houghton AN. Implicating a role for immune recognition of self in tumor rejection: passive immunization against the brown locus protein. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1609–1614. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Law LW, Vieira WD, Hearing VJ, Gersten DM. Further studies of the therapeutic effects of murine melanoma-specific monoclonal antibodies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1226:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mujoo K, Kipps TJ, Yang HM, et al. Functional properties and effect on growth suppression of human neuroblastoma tumors by isotype switch variants of monoclonal antiganglioside GD2 antibody 14.18. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2857–2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagy E, Berczi I, Sehon AH. Growth inhibition of murine mammary carcinoma by monoclonal IgE antibodies specific for the mammary tumor virus. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1991;34:63–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01741326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasi ML, Meyers M, Livingston PO, Houghton AN, Chapman PB. Anti-melanoma effects of R24, a monoclonal antibody against GD3 ganglioside. Melanoma Res. 1997;7(Suppl 2):S155–S162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Zhang S, Cheung NK, Ragupathi G, Livingston PO. Antibodies against GD2 ganglioside can eradicate syngeneic cancer micrometastases. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2844–2849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helling F, Shang A, Calves M, et al. GD3 vaccines for melanoma: superior immunogenicity of keyhole limpet hemocyanin conjugate vaccines. Cancer Res. 1994;54:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones PC, Sze LL, Liu PY, Morton DL, Irie RF. Prolonged survival for melanoma patients with elevated IgM antibody to oncofetal antigen. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;66:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacLean GD, Reddish MA, Koganty RR, Longenecker BM. Antibodies against mucin-associated sialyl-Tn epitopes correlate with survival of metastatic adenocarcinoma patients undergoing active specific immunotherapy with synthetic STn vaccine. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:59–68. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller K, Abeles G, Oratz R, et al. Improved survival of patients with melanoma with an antibody response to immunization to a polyvalent melanoma vaccine. Cancer. 1995;75:495–502. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950115)75:2<495::AID-CNCR2820750212>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittelman A, Chen GZ, Wong GY, Liu C, Hirai S, Ferrone S. Human high molecular weight-melanoma associated antigen mimicry by mouse anti-idiotypic monoclonal antibody MK2-23: modulation of the immunogenicity in patients with malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morton DL, Foshag LJ, Hoon DS, et al. Prolongation of survival in metastatic melanoma after active specific immunotherapy with a new polyvalent melanoma vaccine. Ann Surg. 1992;216:463–482. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199210000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riethmuller G, Schneider-Gadicke E, Schlimok G, et al. Randomised trial of monoclonal antibody for adjuvant therapy of resected Dukes’ C colorectal carcinoma. German Cancer Aid 17-1A Study Group. Lancet. 1994;343:1177–1183. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winter SF, Sekido Y, Minna JD, et al. Antibodies against autologous tumor cell proteins in patients with small-cell lung cancer: association with improved survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:2012–2018. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.24.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eggermont AM. Randomized phase III trial comparing postoperative adjuvant ganglioside GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccination versus observation in stage II (T3-T4N0M0) melanoma: Final results of study EORTC 18961. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl 15):8505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.9303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkwood JM, Manola J, Ibrahim J, Sondak V, Ernstoff MS, Rao U. A pooled analysis of eastern cooperative oncology group and intergroup trials of adjuvant high-dose interferon for melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(5):1670–1677. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarhini AA, Stuckert J, Lee S, Sander C, Kirkwood JM. Prognostic significance of serum S100B protein in high-risk surgically resected melanoma patients participating in Intergroup Trial ECOG 1694. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(1):38–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terando AM, Faries MB, Morton DL. Vaccine therapy for melanoma: current status and future directions. Vaccine. 2007;25(Suppl 2):B4–B16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung NK, Saarinen UM, Neely JE, Landmeier B, Donovan D, Coccia PF. Monoclonal antibodies to a glycolipid antigen on human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2642–2649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kushner BH, Kramer K, Cheung NK. Phase II trial of the anti-G(D2) monoclonal antibody 3F8 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4189–4194. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S, Cordon-Cardo C, Zhang HS, et al. Selection of tumor antigens as targets for immune attack using immunohistochemistry: I. Focus on gangliosides. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:42–49. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<42::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al. A phase III randomized trial of the chimeric anti-GD2 antibody ch14.18 with GM-CSF and IL2 as immunotherapy following dose intensive chemotherapy following dose intensive chemotherapy for high-risk neuroblastoma: Childrens’ Oncology Group (COG) study ANBL0032. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolesta E, Kowalczyk A, Wierzbicki A, et al. DNA vaccine expressing the mimotope of GD2 ganglioside induces protective GD2 cross-reactive antibody responses. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3410–3418. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fest S, Huebener N, Weixler S, et al. Characterization of GD2 peptide mimotope DNA vaccines effective against spontaneous neuroblastoma metastases. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10567–10575. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowalczyk A, Wierzbicki A, Gil M, et al. Induction of protective immune responses against NXS2 neuroblastoma challenge in mice by immunotherapy with GD2 mimotope vaccine and IL-15 and IL-21 gene delivery. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1443–1458. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0289-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SK, Ragupathi G, Musselli C, Choi SJ, Park YS, Livingston PO. Comparison of the effect of different immunological adjuvants on the antibody and T-cell response to immunization with MUC1-KLH and GD3-KLH conjugate cancer vaccines. Vaccine. 1999;18:597–603. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kensil CR, Patel U, Lennick M, Marciani D. Separation and characterization of saponins with adjuvant activity fro Quillaja saponaria molina cortex. J Immunol. 1991;146:431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imai M, Landen C, Ohta R, Cheung NK, Tomlinson S. Complement-mediated mechanisms in anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody therapy of murine metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10562–10568. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ragupathi G, Livingston PO, Hood C, et al. Consistent antibody response against ganglioside GD2 induced in patients with melanoma by a GD2 lactone-keyhole limpet hemocyanin conjugate vaccine plus immunological adjuvant QS-21. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5214–5220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorer PA, Kaliss N. The effect of isoantibodies in vivo on three different transplantable neoplasms in mice. Cancer Res. 1959;19:824–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao XJ, Cheung NK. GD2 oligosaccharide: target for cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1995;182:67–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SK, Ragupathi G, Cappello S, Kagan E, Livingston PO. Effect of immunological adjuvant combinations on the antibody and T-cell response to vaccination with MUC1-KLH and GD3-KLH conjugates. Vaccine. 2000;19:530–537. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00195-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cahan LD, Irie RF, Singh R, Cassidenti A, Paulson JC. Identification of a human neuroectodermal tumor antigen (OFA-I-2) as ganglioside GD2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7629–7633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]