Abstract

Mounting evidence shows that selenium possesses chemotherapeutic potential against tumor cells, including leukemia, prostate cancer and colorectal cancer (CRC) cells. However, the detailed mechanism by which sodium selenite specifically kills tumor cells remains unclear. Herein, we demonstrated that supranutritional doses of selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells through reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent modulation of the PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a signaling pathway. First, we found that selenite treatment in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells caused inhibition of AKT and the nuclear accumulation of FoxO3a by western blot and immunofluorescence analyses, respectively, thereby facilitating transcription of the target genes bim and PTEN. Modulation of the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway by chemical inhibitors or RNA interference revealed that these events were critical for selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells. Additionally, we discovered that FoxO3a-mediated upregulation of PTEN exerted a further inhibitory effect on the AKT survival pathway. We also corroborated our findings in vivo by performing immunohistochemistry experiments. In summary, our results show that selenite could induce ROS-dependent FoxO3a-mediated apoptosis in CRC cells and xenograft tumors through PTEN-mediated inhibition of the PI3K/AKT survival axis. These results help to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying selenite-induced cell death in tumor cells and provide a theoretical basis for translational applications of selenium.

Keywords: selenite, apoptosis, AKT, FoxO3a, reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Selenium, an essential metalloid trace element, has been shown to possess chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic efficacy against multiple malignant cancers.1, 2 For example, epidemiologic and preclinical data have shown an inverse relationship between selenium intake and cancer risk in humans.3, 4 However, the precise underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for these anticarcinogenic activities have not been resolved. Sodium selenite, a common form of inorganic selenium, was recently reported to induce apoptosis in several cancer cell lines.5, 6, 7 Our previous findings demonstrated that sodium selenite could specifically kill colorectal cancer (CRC) cells through the induction of apoptosis.8, 9 In the present study, we further delineated the detailed mechanisms underlying selenite-induced apoptosis.

Forkhead box O (FoxO) transcription factors are crucial regulators of diverse cellular activities, such as proliferation, differentiation, defense against oxidative stress, apoptosis and autophagy.10, 11 These factors are also associated with multiple diseases, including cancer.12, 13 The FoxO family members include four highly related factors—FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4 and FoxO614—that can be posttranslationally regulated by various signaling molecules, of which AKT acts as an important upstream regulator.15 AKT directly phosphorylates FoxO family proteins and promotes their degradation. Consequently, less FoxO protein accumulates in the nucleus to execute protranscriptional actions towards target genes involved in cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis, such as bim, puma and p27.16, 17, 18 PI3K/AKT signaling has been shown to be frequently deregulated in various cancers, particularly in CRC.19, 20 Therefore, exploration of the effects of sodium selenite on this signaling pathway and its involvement in apoptosis is of great significance for future clinical applications of selenium.

In the current study, we discovered that selenite conferred its proapoptotic effect through modulation of the PI3K/AKT/FOXO3a signaling hub in both CRC cells and a colon xenograft model. We present clear evidence that sodium selenite inhibited the PI3K/AKT survival pathway in a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent pathway. Furthermore, inhibition of AKT led to the activation of FoxO transcription factors and enhanced the expression of the target genes bim and PTEN; as a result, Bim was shown to promote selenite-induced apoptosis, and PTEN amplified the proapoptotic effect of sodium selenite by inhibiting the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling axis.

Results

Selenite-induced apoptosis is associated with the Src/PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a signaling axis

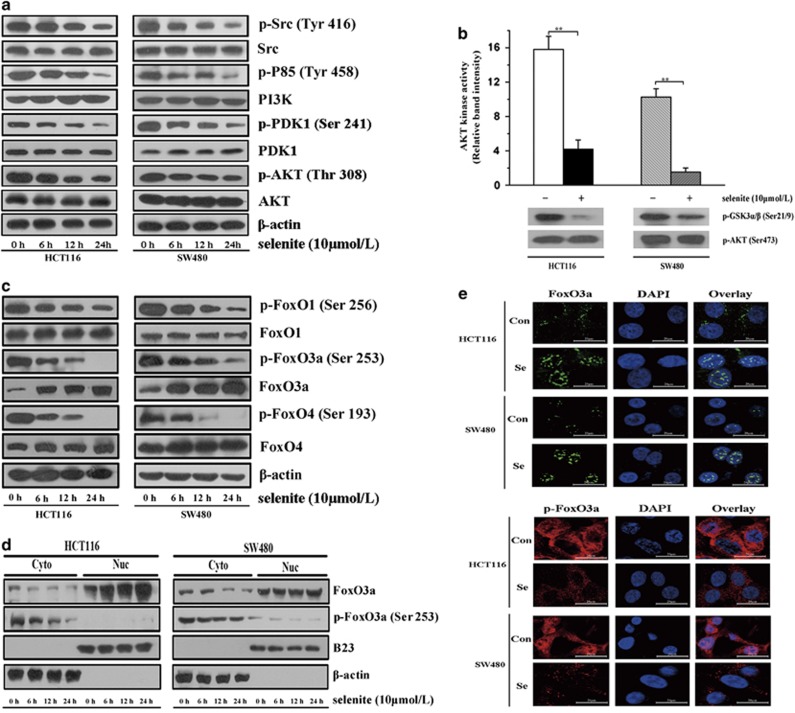

Following our previous study showing that supranutritional doses of selenite induced apoptosis in CRC cells, we aimed to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms. Thus, we conducted experiments to investigate whether selenite could influence the AKT survival pathway in CRC cells. As shown in Figure 1a, we found that supranutritional doses of selenite time-dependently inhibited the Src/PI3K/PDK1/AKT survival pathway in both HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. Additionally, in vitro PI3K and AKT assays (Figure 1b; Supplementary Figure S1) showed that selenite treatment inhibited AKT and PI3K activation in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. We therefore postulated that FoxO family proteins may be regulated by selenite-inhibited AKT. To test this hypothesis, we immunoblotted FoxO family proteins in selenite-treated samples and found that selenite consistently suppressed the phosphorylation of these proteins (Figure 1c), indicating that FoxO proteins may be activated when AKT is inhibited by selenite. To further corroborate this finding, we extracted cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from cells and immunoblotted for FoxO3a and p-Foxo3a in both control and selenite-treated samples and discovered that selenite increased the nuclear levels of FoxO3a but decreased its levels of phosphorylation (Figure 1d). Furthermore, immunofluorescence results (Figure 1e) also supported the above conclusion that selenite induced FoxO3a accumulation in the nucleus. Taken together, these results indicated that selenite inhibited Src/PI3K/PDK1/AKT signaling and activated FoxO family proteins in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells.

Figure 1.

Selenite treatment caused time-dependent inhibition of PI3K/AKT and activation of FoxO proteins. (a) Selenite inhibited the Src/PI3K/PDK1/AKT signaling pathway. Cells were treated with 10 μmol/l selenite for various time periods as indicated and then immunoblotted for p-Src (Tyr 416), Src, p-p85 (Tyr458), p85, p-PDK1 (Ser241), PDK1, p-AKT (Thr308) and AKT. β-Actin was probed to ensure equal protein loading. (b) AKT kinase activity was inhibited by selenite. HCT116 and SW480 cells were treated with either sodium selenite or PBS solution for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were collected after trypsinization and total cellular cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer. p-AKT was captured using from the lysates and the in vitro kinase reaction was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. The relative intensity of the p-GSK3α/β band reflected the AKT kinase activity and p-AKT was immunoblotted as controls. AKT activity was calculated among groups. The error bars represent the mean values±S.D. from at least three independent experiments (**P<0.01). (c) Selenite decreased the phosphorylation of FoxO family proteins and increased the expression of total FoxO proteins. HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells were treated with either selenite or PBS solution for the indicated time periods. Total cellular lysates were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies against p-FoxO1(Ser256), FoxO1, p-FoxO3a (Ser253), FoxO3a, p-FoxO4 (Ser193) and FoxO4. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (d) Selenite treatment induced dephosphorylation of Foxo3a and its nuclear accumulation. Nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were fractioned from selenite-treated HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells and were then subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies against FoxO3a and p-FoxO3a (Ser253). B23 and β-actin were blotted to demonstrate the purity of each fraction. (e) Foxo3a and p-Foxo3a proteins in selenite-treated or control cells were immunostained with primary antibodies and the corresponding FITC- or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by detection using confocal microscopy. Green signals indicate Foxo3a, whereas red signals indicate p-Foxo3a. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Representative images of each sample are shown

AKT/FoxO3a signaling is correlated with selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells

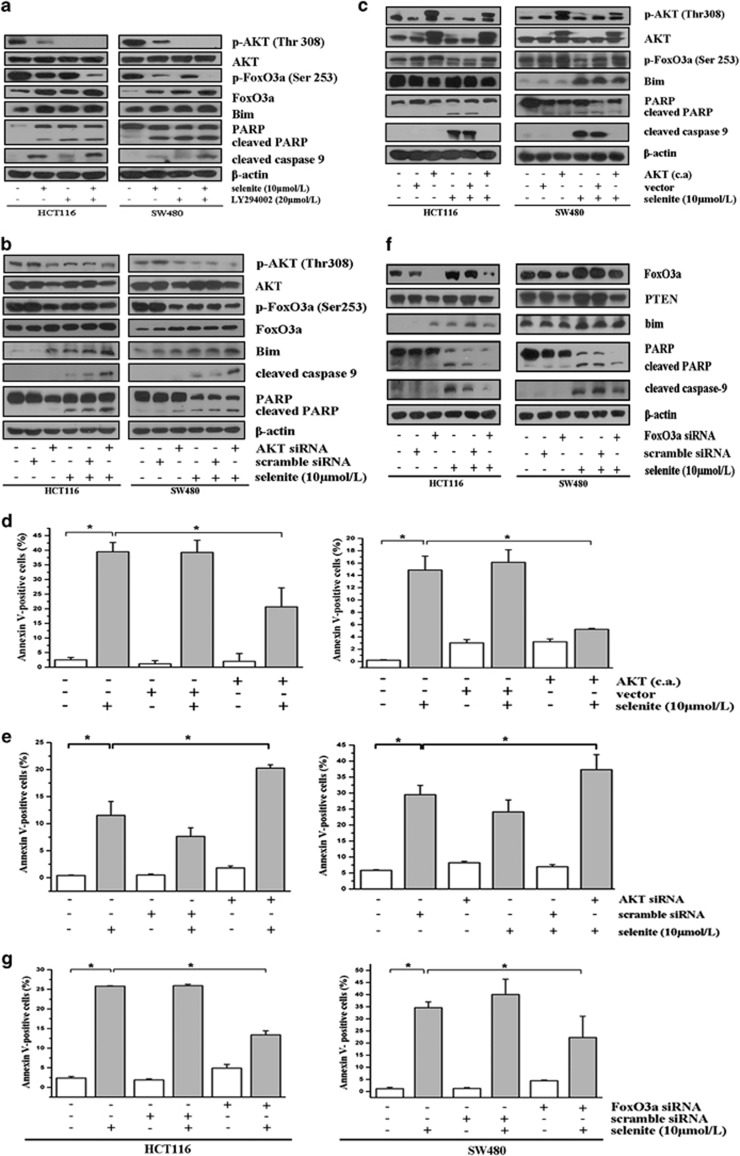

Having discovered that selenite treatment inhibited Src/PI3K/PDK1/AKT signaling and activated FoxO proteins, we conducted a series of experiments to investigate the relationship between AKT and FoxO3a in selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells. On one hand, as revealed in Figures 2a and b, when AKT was inhibited in selenite-treated CRC cells with either the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or AKT siRNA, we found that both treatments further decreased the p-AKT level. As expected, inhibiting AKT further suppressed the phosphorylation of FoxO3a at Ser253 even with selenite treatment. Conversely, when we activated AKT in CRC cells using constitutively activated AKT constructs prior to selenite treatment, we found that, consistent with our hypothesis, constitutively activated AKT increased phosphorylation of AKT and FoxO3a and selenite could no longer reduce phosphorylation of AKT and consequently phosphorylation of FoxO3a (Figure 2c). These results collectively showed that selenite-elicited inhibition of AKT was associated with the activation of FoxO3a. Subsequently, we attempted to determine the role of AKT/FoxO3a in selenite-induced apoptosis of CRC cells. First, from western blot results of the above-mentioned samples, we observed that reactivation of AKT resulted in less cleavage of apoptosis-related markers such as caspase 9 and PARP, whereas further inhibition of AKT led to additional cleavage of these apoptosis-related markers. Analysis of the apoptotic rate by FACS using cells treated as indicated in the panels of Figures 2d and e and Supplementary Figures S2A and B demonstrated that AKT reactivation or inhibition could blunt or enhance, respectively, the apoptosis of CRC cells treated with selenite. Complementary to the above results, silencing FoxO3a with siRNA specifically decreased the level of apoptosis in selenite-treated CRC cells, as revealed by western blotting and FACS (Figures 2f and g; Supplementary Figure S2C). Thus, these findings clearly demonstrate that selenite induced apoptosis in CRC cells through regulation of the AKT/FoxO3a pathway.

Figure 2.

Selenite-induced inhibition of AKT directly activated FoxO3a in CRC cells, an event closely correlated with apoptosis. (a, b) Inhibition of AKT with either LY294002 or AKT siRNA led to an inhibition of FoxO3a and increased apoptosis in selenite-treated HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. Cells were treated with LY294002 for 1 h prior to selenite treatment or were transfected with AKT siRNA followed by treatment with either selenite or PBS for 24 h. Cells were then collected, and total cellular lysates were immunoblotted for p-AKT (Thr308) and p-Foxo3a (Ser253), Bim, cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 9 and β-actin. (c) Activation of AKT protected cells from selenite-induced apoptosis and modulation of AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling. HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells were transfected with constitutively activated (c.a.) AKT constructs to restore AKT prior to selenite treatment for 24 h and were then subjected to western blot assays using antibodies against p-AKT, AKT, p-FoxO3a, Bim, cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 9. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (d, e) The apoptotic rate of cells was determined by FACS in cells transfected with constitutively activated (c.a.) AKT constructs or AKT siRNA and treated with selenite. The results were calculated and are statistically represented as bar graphs. *P<0.05 indicates statistical significance between groups. (f, g) Foxo3a-mediated selenite-induced apoptosis downstream of AKT. Cells were transfected with FoxO3a siRNA prior to treatment with selenite for 24 h, after which time apoptosis was analyzed using western blotting or FACS

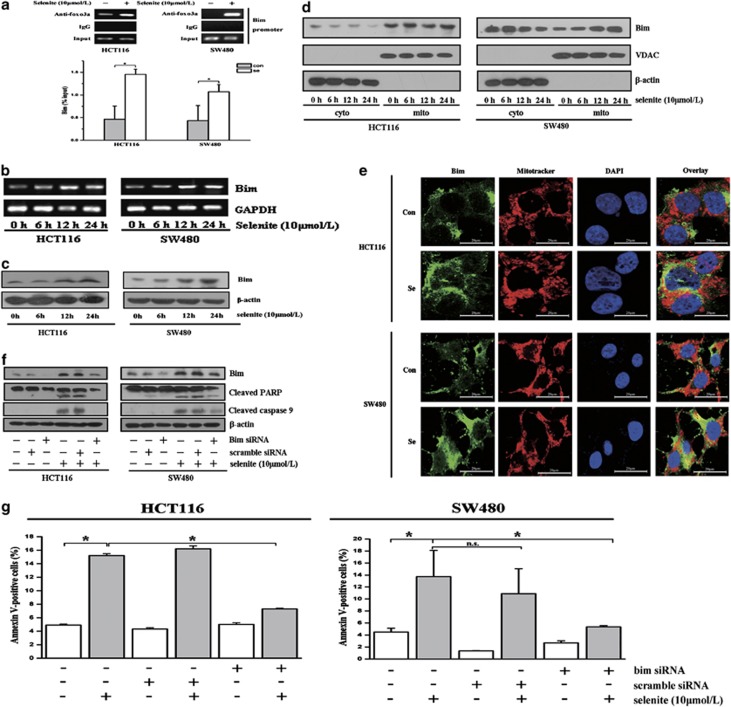

Bim acts as a pivotal downstream factor of FoxO3a and thereby contributes to apoptosis

Accumulated FoxO3a in the nucleus can bind to promoters containing a consensus sequence to enhance the transcription of various molecules involved in apoptosis and the cell cycle, such as bim, puma, p27 and p21.21 Our previous results showed that Bcl-2 family proteins are critical regulators of selenite-induced apoptosis.22 Thus, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments to examine whether selenite could influence the binding of FoxO3a to the bim promoter to drive bim transcription. Indeed, as shown in Figure 3a, selenite treatment in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells enhanced FoxO3a binding to the bim promoter, thus enhancing its transcription (Figure 3b). Accordingly, western blot results also showed that selenite treatment enhanced the expression of bim (Figure 3c). To explore whether Bim participated in selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells, we separated mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions from selenite-treated cells, immunoblotted for Bim and found that selenite treatment could induce the translocation of Bim from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria (Figure 3d). Moreover, immunostaining for Bim in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells also corroborated the finding that selenite induced the colocalization of Bim with the mitochondria (Figure 3e). Finally, to further confirm the role of Bim in apoptosis, we knocked down the expression of Bim with siRNA in cells treated with selenite and found that Bim silencing markedly blocked selenite-induced apoptosis in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells, as demonstrated by western blotting and FACS. (Figures 3f and g; Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 3.

FoxO3a promoted the transcription and expression of bim, thereby enhancing apoptosis. (a) Selenite facilitated FoxO3a binding to the bim promoter. HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells were treated with or without selenite for 24 h followed by subjection to the ChIP assay. The relative band intensity of PCR products revealed the binding of FoxO3a to the bim promoter. (b, c) Selenite increased the transcription of bim in both HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. Cells were treated with selenite for the indicated time periods followed by reverse transcription PCR and western blotting. (d) Selenite treatment caused the translocation of Bim from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells were treated with selenite for the indicated time periods, and the mitochondria were then isolated and immunoblotted for Bim. VDAC and β-actin were used as markers of the mitochondria and cytoplasm, respectively. (e) Colocalization results of Bim in selenite-treated HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. Cells were treated with selenite for 24 h, and Mitotracker (red) solution was added to the medium to stain the mitochondria in cells. Cells were collected and stained with a Bim primary antibody and a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Nuclei are shown as blue signals. (f, g) Knockdown of Bim attenuated apoptosis in selenite-treated CRC cells. Bim siRNA was used to silence the expression of bim in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells that subsequently were treated with selenite for 24 h. All groups of cells were analyzed using western blotting and FACS

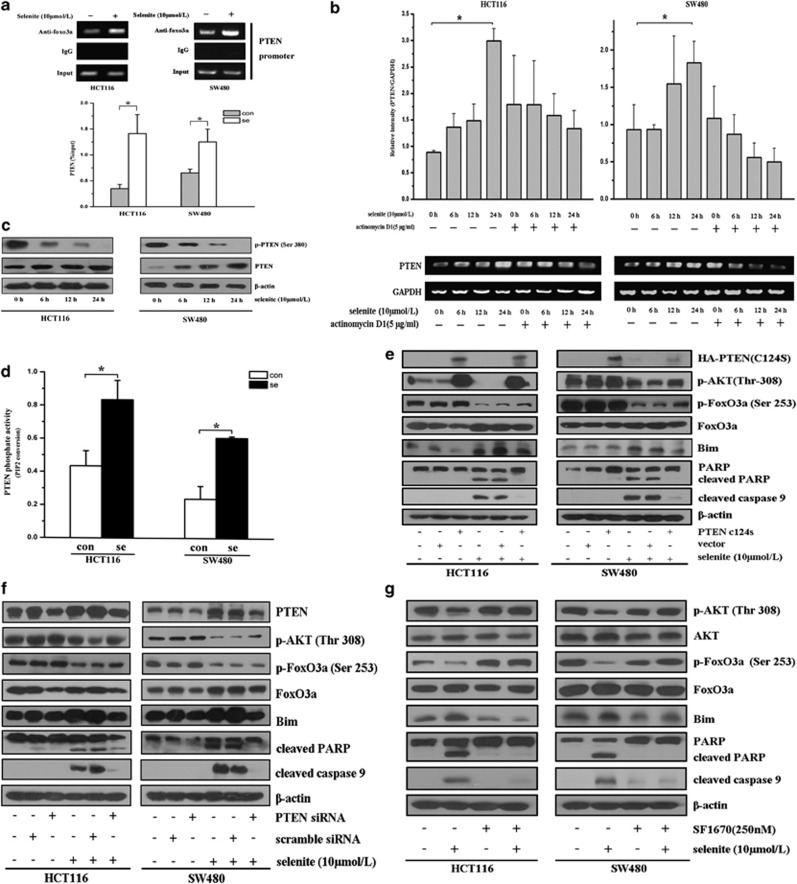

FoxO3a-upregulated PTEN expression is involved in regulating selenite-induced changes in the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway

In our experiments, we unexpectedly found that selenite-induced FoxO3a also binds to the promoter of the PTEN gene (Figure 4a) in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells, a finding also mentioned by Chiacchiera et al.23 Further experiments indicated that FoxO3a directly facilitated PTEN transcription rather than blocking its degradation, as an mRNA synthesis inhibitor clearly inhibited the increase in PTEN mRNA after selenite treatment (Figure 4b). Moreover, the expression of PTEN also increased in a time-dependent manner after selenite treatment (Figure 4c). PTEN activity in selenite-treated cells was also enhanced in both cell lines (Figure 4d). To clarify whether upregulation of PTEN could indeed affect the AKT/FoxO3a signaling pathway, we knocked down PTEN expression or transfected cells with a phosphatase-dead (C124S) mutant. As shown in Figures 4e and f, PTEN knockdown reversed the changes elicited by selenite in both cell lines. In addition, the inhibition of PTEN by SF167024 abrogated the changes in the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim pathway induced by upregulated PTEN (Figure 4g). From these results, we concluded that selenite-induced inhibition of AKT and the activation of FoxO3a/Bim as well as apoptosis were critically regulated by increased levels of PTEN.

Figure 4.

Selenite-induced PTEN modulated the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway. (a) Selenite treatment facilitated the binding of FoxO3a to the PTEN promoter. HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells were treated with selenite for 24 h and then were subjected to ChIP analysis. The binding ability of FoxO3a to the PTEN promoter was calculated and analyzed. (b) Selenite treatment enhanced the synthesis of PTEN mRNA through FoxO3a accumulation in the nucleus. HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells were treated for the indicated time periods with or without actinomycin D1 to inhibit new mRNA synthesis. Total cellular mRNA was then extracted and subjected to reverse transcription PCR. The PTEN mRNA level was determined and calculated from three independent experiments. (c) The expression of PTEN was enhanced in selenite-treated CRC cells. Western blotting was performed to determine the expression of PTEN in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells after selenite treatment. (d) Selenite enhanced PTEN phosphatase activity in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. Twenty-four hours after selenite treatment, cells were collected, and PTEN phosphatase activity in each sample was determined as described in the Materials and Methods section. (e, f) PTEN perturbed the selenite-regulated AKT/FoxO3a signaling axis. Cells were transfected with phosphatase-dead PTEN (C124S) plasmids or PTEN siRNA to efficiently extinguish PTEN activity. Subsequently, cells were treated with or without selenite for 24 h, and then the expression levels of p-AKT (Thr308), p-FoxO3a (Ser253), FoxO3a, Bim, cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 9 were detected using western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (g) Inhibition of PTEN abrogated the further inhibitory effect of PTEN on the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway. HCT116 and SW480 cells were treated with SF1670, a PTEN inhibitor, followed by selenite or PBS for 24 h. The altered expression patterns of p-AKT, AKT, p-FoxO3a, FoxO3a, cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 9 were determined using western blotting. β-Actin was used as a control for equal loading

Selenite-induced ROS are indispensable for AKT/FOXO3a/Bim-mediated apoptosis in CRC cells

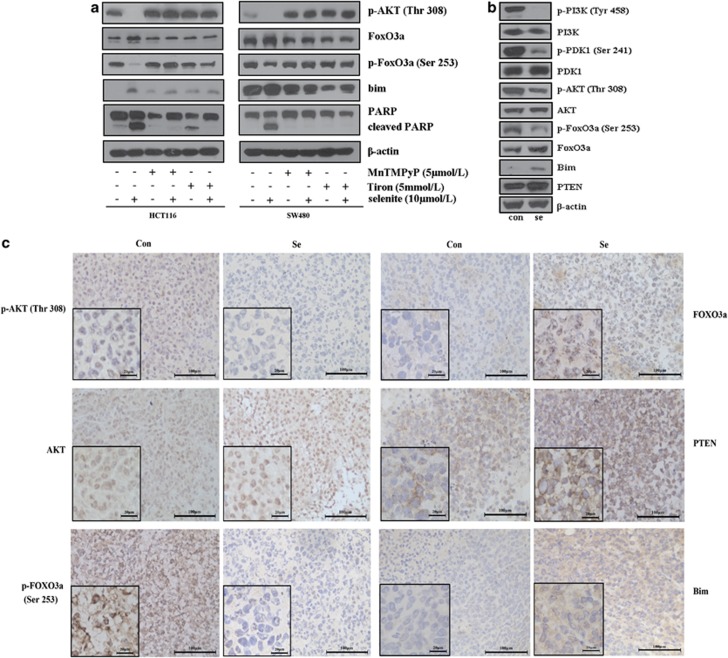

Previous work, including our own, has identified ROS as an important factor in the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells.25, 26, 27 Our previous work showed that sodium selenite treatment could induce an increased level of ROS in CRC cells.9 Thus, we conducted experiments to elucidate whether ROS were involved in selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells. To explore the possible link between ROS and AKT/FOXO3a/Bim-mediated apoptosis, we eliminated ROS in selenite-treated cells using a MnSOD mimic, the widely used ROS scavenger MnTMPyP or another ROS extinguisher (Tiron) and found that depletion of ROS almost completely blocked apoptosis induced by selenite, as observed by the disappearance of cleaved PARP. Furthermore, this signaling pathway regulated by selenite that was also relieved by ROS depletion strongly argues for a role of ROS in selenite-induced AKT/FOXO3a/Bim-mediated apoptosis in CRC cells (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) ROS were involved in selenite-mediated regulation of the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. Cells samples were pretreated with MnTmPyP or Tiron solution and then were treated with selenite or PBS for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blot for the molecules shown in the figures. (b) Western blot analysis of proteins extracted from tumor tissues using antibodies against critical molecules as indicated. (c) Selenite-mediated regulation of the PTEN/AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway in vivo. Tumor tissues from a colon xenograft animal model were subjected to immunohistochemistry analysis using antibodies recognizing p-AKT (Thr308), AKT, p-FoxO3a (Ser253), FoxO3a, PTEN and Bim. Representative images from both control and selenite-treated samples are shown

The PTEN/AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway is regulated by selenite in vivo

Having defined the role of PTEN/AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling in selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells, we sought to test whether selenite could regulate this signaling pathway in vivo. We previously observed that selenite treatment could markedly inhibit tumor growth and induce apoptosis in a SW480 colon xenograft model.8 To verify these results in additional tissues, we first performed western blot analysis of tissues from both control and selenite-treated samples, and the results revealed that selenite could inhibit the phosphorylation of PI3K/PDK1/AKT and FoxO3a, thereby upregulating Bim and PTEN (Figure 5b). Additionally, in a series of immunohistochemistry experiments, we examined the expression patterns of critical molecules in this signaling pathway, including p-AKT, AKT, FoxO3a, p-FoxO3a, Bim and PTEN, and discovered that each of these proteins displayed a similar pattern as that seen in tumor cell lines (Figure 5c; Supplementary Figure S5).

Discussion

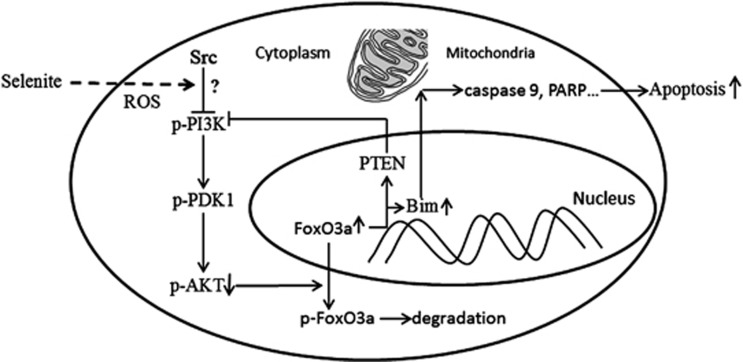

The present study presents evidence that the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim/PTEN signaling axis is closely associated with selenite-induced apoptosis in CRC cells and xenograft tumors. A model depicting our findings is shown in Figure 6. Together, our results suggest that supranutritional doses of selenite inhibit Src/PI3K/PDK1/AKT signaling and activate FoxO proteins. Further experiments revealed that inhibiting or activating AKT genetically or pharmacologically together with selenite treatment resulted in the further regulation of FoxO3a as well as its target bim. We also confirmed that selenite-induced activation of FoxO3a could enhance the transcription of bim and PTEN via increased promoter binding of FoxO3a. Enhanced levels of bim were further shown to translocate from the cytoplasm to mitochondria, which played a crucial role in the activation of caspase 9 and PARP resulting from selenite treatment. Furthermore, we found that FoxO3a-induced PTEN played a role in the selenite-regulated AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway, further amplifying the proapoptotic effect of selenite. Moreover, depletion of ROS via treatment with MnTmPyP or Tiron in selenite-induced cells reversed the changes observed in the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway, implying that ROS may be involved in selenite-induced regulation of the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells.

Figure 6.

A schematic illustration delineating the role of the AKT/Foxo3a/Bim pathway in selenite-induced apoptosis of CRC cells. Selenite treatment inhibited Src/PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway and accumulation of FoxO3a in the nucleus possibly through induced ROS in CRC cells. On one hand, upregulated FoxO3a enhanced the transcription and expression of bim, which led to apoptosis. Additionally, PTEN was also upregulated by FoxO3a, indicating further regulation of AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling and apoptosis in response to selenite

FoxO family proteins have emerged as master regulators that control a plethora of cellular activities through the orchestration of different patterns of gene expression in response to diverse stimuli.28 Notably, studies by the group of David T Scadden revealed a role for FoxO3a in maintaining a differentiation blockade in AML cells,29 which is in contrast to its canonical tumor suppressor role. Furthermore, these cells could be regulated by many upstream factors such as AKT, ERK, IKKβ and JNK under different contexts.30, 31, 32, 33 In the present study, we focused on the effect of AKT on FoxO3a and its downstream targets because AKT was shown to be aberrantly expressed in multiple malignant tumors, particularly in CRC. Thus, exploring the molecular mechanisms of drugs targeting AKT could be of great significance for treating cancer, particularly for tumors harboring aberrantly upregulated AKT activity. First, we found that selenite inhibited AKT and its canonical upstream regulator PI3K and PDK1. We demonstrated that AKT inhibition directly activated FoxO3a in response to selenite, an event crucial for selenite-induced apoptosis. The AKT/FoxO3a signaling hub has also been shown to be regulated by many other chemotherapy drugs, such as 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, isoflavone and paclitaxel.34, 35, 36 FoxO3a is phosphorylated by AKT at Thr32, Ser256 and Ser319, and phosphorylation of these amino acids provides binding sites for 14-3-3 proteins, resulting in the retention of FoxO3a by 14-3-3 in the cytoplasm. Accordingly, selenite treatment drastically decreased 14-3-3 binding sites on FoxO3a proteins, indicating that FoxO3a was retained in the nucleus (Supplementary Figure S2D). Furthermore, inhibition of AKT by selenite was shown to be directly related to the reduced phosphorylation of FoxO3a (Figures 2a and b), which resulted in FoxO3a accumulation in the nucleus. This prompted us to further investigate the role of FoxO3a in the nucleus following treatment with selenite in CRC cells.

Bim is widely known for its pro-apoptotic functions in mitochondria, and it induces apoptosis by interacting with proteins harboring anti-apoptotic function such as Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. Such interactions release proteins, including Bax and Bak, at the mitochondria to initiate apoptosis.37, 38 Bim was also shown to be a direct target of FoxO3a.39 In the present study, we found that activated FoxO3a could bind more intensely to the promoter of bim, thereby facilitating bim transcription. In parallel, an increased Bim level was correlated with translocation from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria, and knockdown experiments showed that selenite-induced bim expression was involved in selenite-induced apoptosis.

PTEN is commonly mutated in various cancers,40, 41 as it normally functions as a tumor suppressor to antagonize the effects of PI3K through its lipid phosphatase activity. Consequently, AKT activation is balanced by both PTEN and PI3K. In the present study, we observed that selenite inhibited the phosphorylation of Src and the p85 subunit of PI3K and its downstream effectors PDK1 and AKT. Additionally, PTEN expression was upregulated by FoxO3a and (Figures 2f and 4c), and PTEN activity was enhanced in response to selenite treatment (Figure 4d). These findings are supported by work from Meuillet and coworkers.42 Therefore, we hypothesized that selenite-induced activation of PTEN was involved in regulation of the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway. We transfected cells with lipid phosphatase-dead PTEN plasmids or PTEN siRNA as well as inhibiting PTEN with SF1670 and discovered that selenite-mediated modulation of the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim pathway was abrogated when PTEN was inhibited. Furthermore, activating PTEN with NaBT in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells exerted further inhibitory effects on the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway (Supplementary Figure S4). We concluded that selenite-induced PTEN was associated with the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim pathway and apoptosis in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells, which is consistent with the findings from other groups showing that PTEN directly regulates AKT/FoxO3a under various circumstances.43, 44 However, whether a positive feedback loop exists between PTEN and the AKT/FoxO/Bim signaling pathway requires further study.

Our previous results, along with the findings of other studies, have implicated ROS as a potential mediator of selenite-induced apoptosis and its related signaling pathway in tumor cells.5, 7, 9 To define the role of selenite-induced ROS in the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway, we inhibited selenite-induced ROS in CRC cells and observed that the above change in the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim pathway was blocked completely. Additionally, selenite-induced apoptosis was blunted when cells were pretreated with ROS scavengers. Thus, the selenite-regulated PTEN/AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling hub and apoptosis are critically modulated by ROS in HCT116 and SW480 cells. However, much work still needs to be done to clarify the relationship between ROS and selenite-modulated FoxO proteins, as work by Schulze coworkers45 found that FoxO proteins could reduce the ROS level in cells by impairing the expression of genes with mitochondrial function rather than in the canonical SOD2-independent manner. Moreover, work by Yoon et al.46 concluded that selenite inhibits apoptosis through activation of PI3K/AKT signaling, and Xiangjia Zhu together with his colleagues discovered that selenite inhibits 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene-induced apoptosis in human lens epithelial cells through activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway.47 However, it should be noted that the concentration of selenite used in these previous studies was very low (2–3 μmol/l) and was a physiological dose that caused different effects regarding cell survival and the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Our previous study also provided evidence that low-dose selenite could promote cell survival, whereas supranutritional doses of selenite could induce apoptosis in CRC cells.48 The effects of selenite on cell fate and regulation of this signaling axis depend on the doses and different cellular systems, which also applies to in vivo experiments. Although we used a colon xenograft model to strengthen our findings, we paid much attention to the heterogeneity of cancer cells when reaching our conclusion. Thus, much work needs to be done to define the role of selenite in vivo, which is a main focus of our future research.

In summary, the ensemble of evidence presented in the current study demonstrates that sodium selenite could induce apoptosis specifically in CRC cells by inhibiting Src/PI3K/AKT survival factors and activating FoxO proteins along with the targets bim and PTEN. Activated FoxO3a bound more intensely to the Bim and PTEN promoters, thereby enhancing their transcription and expression, and our immunofluorescence and western blot results both demonstrated that increased levels of Bim translocated from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. Furthermore, RNA interference experiments revealed that this process was essential for selenite-induced apoptosis. Selenite-induced PTEN further amplified this effect on the AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling pathway. However, whether selenite can directly affect PTEN activity through somehow mechanisms warrants further study. These findings help to elucidate the molecular effects of selenite treatment and provide a theoretical basis for its clinical application, and exploration of the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying the efficacy of selenite in treating malignant cancer is of great significance for translational medicine.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture

The human CRC cell lines HCT116 and SW480 were purchased from the cell culture center of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. All cell cultures were monitored routinely, all cell lines were discarded after 2 months, and new lines were propagated from the frozen stocks.

Reagents and antibodies

Sodium selenite, Tiron, NaBT and SF1670 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). A 10 mmol/l stock solution of selenite was prepared by dissolving selenite powder in sterile PBS solution, and a final 10 μmol/l working solution was used in the current study (as determined previously). LY294002 was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Manganese (III) tetrakis (1-methyl-4-pyridyl) porphyrin (MnTMPyP) was purchased from Merck Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Insulin was purchased from Roche (Auckland, NZ, USA). Actinomycin D and DAPI were purchased from Beyotime (Haimen, Jiangsu, China).

The antibody against β-actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies recognizing cleaved caspase 9, cleaved PARP, p-Src (Tyr416), Src, p-p85 (Tyr458), p85, p-PDK1 (Ser241), PDK1, p-AKT(Thr308), AKT, p-FoxO1 (Ser256), FoxO1, p-FoxO4 (Ser193), FoxO4, the Pho-(Ser) 14-3-3 binding motif, PTEN, Bim, p-PTEN(Ser380), Myc-tag, VDAC and HA-tag were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies against B23, FoxO3a and p-FoxO3a (Ser253) were obtained from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Immunoblotting

To prepare lysates, cells were collected after trypsinization and washed twice with cold PBS. Total cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin and 1 mM PMSF). Specifically, nuclear fractions were obtained using the NE-PER nuclear/cytoplasmic extraction kit. Mitochondria were fractionated using the Mitochondria Isolation Kit for Mammalian Cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The protein concentration in each sample was determined using the Bradford assay. After normalization, equal amounts of proteins were fractionated on 8–15% SDS-PAGE gels. The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and incubated with the indicated primary antibodies and corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. The immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA).

Plasmids transient transfection analysis

Approximately 4 × 105 cells were plated into six-well plate 1 day before transfection experiments to allow for cell attachment and growth. When grown to 50% confluency, cells were transfected with indicated plasmids by lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), according to the protocol. Briefly, about 4 μg plasmids were transfected into cells together with 5 μl lipofectamine 2000 reagent per well. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated as indicated.

Small interfering RNAs

AKT1 siRNA (5′-AAGGAGGGUUGGCUGCACAAA-3′); FOXO3a siRNA (5′-AAUGUGACA-UGGAGUCCAUUA-3′); Bim siRNA (5′-AAGGUAGACAAUUGCAGCCUG-3′); PTEN si RNA (5′-GACUUGAAGGCGUAUACAGtt-3′) and the control siRNA (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCA-CGUTT3′) were chemically synthesized by GenePharm (Shanghai, China). Cells cultured in six-well plates were transfected with 100 pM siRNA by lipofectamine 2000 according to the guideline as described above. Cells were then subjected to further treatment as demanded.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested and total cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer. In all, 200 μg aliquots of lysates were immunoprecipitated by the appropriate antibodies and normal immunoglobulin antibodies as a control. The immunoprecipitates were then captured by 25 μl protein A+G agarose beads (Santa Cruz). After being washed and elutioned, the immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blot assays.

PI3K kinase assay

The in vitro kinase activity of PI3K in our study was examined using the PI3-Kinase Activity Assay Kit from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake, UT, USA). Briefly, cells were treated as indicated, and then PI3K was immunoprecipitated from cellular lysates using PI3K antibodies. Kinase reactions were performed using PI2P as the substrate. The production of PI3P in each sample was detected using ELISA, according to the methods provided by the manufacturer. The relative activity of PI3K could be calculated based on the concentration of PI3P in each group.

AKT kinase assay

The in vitro kinase activity of AKT kinase in cells treated with or without selenite was determined using the Akt Kinase Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology). Briefly, cells were harvested, and cell lysates were prepared in cell lysis buffer provided by the manufacturer. Subsequently, immobilized Akt antibody was used to immunoprecipitate p-AKT from cell lysates followed by in vitro detection of Akt kinase activity using GSK-3 fusion protein and cold ATP in the kinase buffer. Finally, the activity of AKT kinase in each sample was determined according to GSK-3α/β phosphorylation by western blotting.

In vitro phosphatase activity assay of PTEN

The phosphatase activity of PTEN was determined using the Malachite Green Assay Kit from Echelon Biosciences. Briefly, PTEN was immunoprecipitated from treated cells using PTEN monoclonal antibodies. After thorough washing and purification, the immunocomplexes were dissolved in the enzyme reaction buffer. The enzyme reaction was initiated using the PIP3 substrate provided by the manufacturer. Malachite green solution was added at the termination of the enzyme reaction. The absorbance of the solution was then read in each well. The relative conversion of PI3P to PI2P was calculated to reflect the phosphatase activity of PTEN.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase, oligo dT primer and dNTPs (Promega), and the resultant cDNA was subjected to PCR. Primers for PTEN (forward: 5′-CCAATGTTCAGTGGCGGAACT-3′ reverse: 5′-GAACTTGTCTTCCCGTCGTGTG-3′), Bim (forward: 5′-GAGCCACAAGACAGGAGC-3′ reverse: 5′-AAGGGCAATTCT-GAGGGA-3′) and GAPDH (forward: 5′-CATCTTCCAGGAGC-GAGATC-3′ reverse: 5′-GCTTGA-CAAAGTGGTCGTTG-3′) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai Co. Ltd., China). The band intensities of each band were normalized to the corresponding GAPDH bands.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown on coverslips for 24 h before treatment with 10 μmol/l selenite or PBS solution for 24 h. Cells were then fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 solution for 10 min. After thorough washing with PBS three times, each for 5 min, the samples were blocked with 2% BSA solution for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, slides were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Thereafter, cells were incubated with FITC- or Cy3-labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, followed by counterstaining with DAPI solution. Images were acquired using an Olympus laser scanning confocal FV1000 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed using Olympus Fluoview software. Representative images are shown in figures with identical settings.

Apoptosis assay

The percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was determined using Annexin V/PI double staining with the Apoptosis Detection Kit from Merck Calbiochem. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after performing the indicated treatments, cells were harvested and washed twice with pre-cold PBS buffer, and then cells were stained with Annexin V and PI in 1 × binding buffer. The percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was determined using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Accuri Cytometers Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All experiments were performed three times independently, and the results are expressed as the mean values±S.D.

ChIP assay

ChIP assays were performed using the SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the proteins were crosslinked to DNA in live nuclei using 1% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). The crosslinked chromatin was extracted from cells using buffer A and buffer B provided in the ChIP kit and then digested using micrococcal nuclease for 20 min at 37 °C into small fragments. The crosslinked chromatin was aliquoted and immunoprecipitated using 2 μg of foxo3a antibody and normal rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody overnight at 4 °C with gentle rotation. The complexes were captured by ChIP-Grade Protein G agarose beads for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation. Following thorough washing, bound DNA fragments were eluted and analyzed by subsequent PCR using primers for PTEN and bim as follows: PTEN: forward 5′-GCATTTCCGAATCAGCTCTCT-3′ reverse: 5′-CCAAGTGACTTATCTCTGGTCTGAG-3′ and bim: forward 5′-AGGCAGAACAGGAGGAGA-3′ reverse 5′-AACCCGTTTGTA-AGAGGC-3′.

Immunohistochemistry evaluation

The colorectal xenograft model was established as previously described.8 All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines issued by the committee on animal research of Peking Union Medical College and approved by the institutional ethics committee. At the termination of the experiments, tumor tissues from both the control and selenite-treated groups were sectioned. Half of these samples were homogenized and subjected to western blotting as described above, whereas the remaining tissues were embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemical analysis. First, 4 μm thick tissue sections were prepared on slides and then were dewaxed and rehydrated in xylene and graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was achieved by heating the slides in a 95 °C water bath with 0.01 mol/l citrate buffer at pH 6.0 for 20 min. Subsequently, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution (Zhongshan Gold Bridge, Beijing, China). Thereafter, slides were blocked with 10% goat serum for 0.5 h after which the sections were incubated with primary antibodies as indicated in the figures (Figure 5c and Supplementary Figure S5) for 1 h. After three sequential washes (5 min each) in PBS solution, these samples were incubated with a streptavidin–peroxidase complex for an additional 1 h. All of the above procedures were performed at room temperature. Next, a diaminobenzidine working solution was applied after additional washes. Finally, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. For all the quantitative analyses represented in the histograms, the values are expressed as the mean values±S.D. The significance of the differences between mean values were assessed using Student's t-test. All computations were calculated using the Microsoft Excel program.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Wenji Dong for his AKT plasmids and kind suggestions. This work was supported by the grants from National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scholars of China (Grant No. 31101018), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31170788 and No. 30970655), State Key Laboratory Special Fund (No. 2060204) and Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (No. 20091106110025).

Glossary

- FACS

fluoresence activated cell sorting

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- Bim

Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Stephanou

Supplementary Material

References

- Rayman MP. Selenium and human health. Lancet. 2012;379:1256–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozmanova J. [Selenium and cancer: from prevention to treatment] Klin Onkol. 2011;24:171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LC, Dalkin B, Krongrad A, Combs GF, Turnbull BW, Slate EH, et al. Decreased incidence of prostate cancer with selenium supplementation: results of a double-blind cancer prevention trial. Br J Urol. 1998;81:730–734. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LC, Combs GF, Turnbull BW, Slate EH, Chalker DK, Chow J, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial. Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. JAMA. 1996;276:1957–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Kim JH, Chi GY, Kim GY, Chang YC, Moon SK, et al. Induction of apoptosis and autophagy by sodium selenite in A549 human lung carcinoma cells through generation of reactive oxygen species. Toxicol Lett. 2012;212:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XJ, Duan FD, Zhang HH, Xiong Y, Wang J. Sodium selenite-induced apoptosis mediated by ROS attack in human osteosarcoma U2OS cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012;145:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan L, Han B, Li Z, Hua F, Huang F, Wei W, et al. Sodium selenite induces apoptosis by ROS-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in human acute promyelocytic leukemia NB4 cells. Apoptosis. 2009;14:218–225. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Nie C, Yang Y, Yue W, Ren Y, Shang Y, et al. Selenite induces redox-dependent Bax activation and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Yang Y, Huang F, Li F, Jiang Q, Shi K, et al. Selenite induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells via AKT-mediated inhibition of beta-catenin survival axis. Cancer Lett. 2012;315:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam EW, Francis RE, Petkovic M. FOXO transcription factors: key regulators of cell fate. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34 (Pt 5:722–726. doi: 10.1042/BST0340722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vos KE, Gomez-Puerto C, Coffer PJ. Regulation of autophagy by Forkhead box (FOX) O transcription factors. Advances Biol Regul. 2012;52:122–136. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z, FOXOs TindallDJ. cancer and regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:2312–2319. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gan B, Liu D, Paik J-h. FoxO family members in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:253–259. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.4.15954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden KC. Multiple roles of FOXO transcription factors in mammalian cells point to multiple roles in cancer. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:709–717. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan DR, Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H, Brunet A, Griffith EC, Greenberg ME. The many forks in FOXO's road. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.172.re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon C, Wang P, Sun X, Peng R, Sun Q, Yu J, et al. PUMA induction by FoxO3a mediates the anticancer activities of the broad-range kinase inhibitor UCN-01. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2893–2902. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl M, Dijkers PF, Kops GJ, Lens SM, Coffer PJ, Burgering BM, et al. The forkhead transcription factor FoxO regulates transcription of p27Kip1 and Bim in response to IL-2. J Immunol. 2002;168:5024–5031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy HK, Olusola BF, Clemens DL, Karolski WJ, Ratashak A, Lynch HT, et al. AKT proto-oncogene overexpression is an early event during sporadic colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:201–205. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altomare DA, Testa JR. Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:7455–7464. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KL, Sun YJ, Huang CY, Yang JY, Hung MC, Hsiao CD. Crystal structure of the human FOXO3a-DBD/DNA complex suggests the effects of post-translational modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6984–6994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao TM, Hua FY, Xu CM, Han BS, Dong H, Zuo L, et al. Distinct effects of different concentrations of sodium selenite on apoptosis, cell cycle, and gene expression profile in acute promyeloytic leukemia-derived NB4 cells. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:434–442. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-0046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiacchiera F, Matrone A, Ferrari E, Ingravallo G, Lo Sasso G, Murzilli S, et al. p38α blockade inhibits colorectal cancer growth in vivo by inducing a switch from HIF1α- to FoxO-dependent transcription. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1203–1214. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Prasad A, Jia Y, Roy SG, Loison F, Mondal S, et al. Pretreatment with phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) inhibitor SF1670 augments the efficacy of granulocyte transfusion in a clinically relevant mouse model. Blood. 2011;117:6702–6713. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozmanova J, Manikova D, Vlckova V, Chovanec M. Selenium: a double-edged sword for defense and offence in cancer. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84:919–938. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang N, Zhao R, Zhong W. Sodium selenite induces apoptosis by generation of superoxide via the mitochondrial-dependent pathway in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:351–362. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0745-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralova V, Benesova S, Cervinka M, Rudolf E. Selenite-induced apoptosis and autophagy in colon cancer cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2012;26:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter ME, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R113–R114. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes Stephen M, Lane Steven W, Bullinger L, Kalaitzidis D, Yusuf R, Saez B, et al. AKT/FOXO signaling enforces reversible differentiation blockade in myeloid leukemias. Cell. 2011;146:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J-Y, Zong CS, Xia W, Yamaguchi H, Ding Q, Xie X, et al. ERK promotes tumorigenesis by inhibiting FOXO3a via MDM2-mediated degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:138–148. doi: 10.1038/ncb1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Lee DF, Xia W, Golfman LS, Ou-Yang F, Yang JY, et al. IkappaB kinase promotes tumorigenesis through inhibition of forkhead FOXO3a. Cell. 2004;117:225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen WR, Xing D. A pathway from JNK through decreased ERK and Akt activities for FOXO3a nuclear translocation in response to UV irradiation. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1168–1178. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Kar S, Palit S, Das PK. 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid induces apoptosis through modulation of Akt/FOXO3a/Bim pathway in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1923–1931. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D, Li R, Sarkar SH, Sarkar FH. Regulation of Akt/FOXO3a/GSK-3/AR signaling network by isoflavone in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27707–27716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802759200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunters A, Madureira PA, Pomeranz KM, Aubert M, Brosens JJ, Cook SJ, et al. Paclitaxel-induced nuclear translocation of FOXO3a in breast cancer cells is mediated by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:212–220. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor L, Strasser A, O'Reilly LA, Hausmann G, Adams JM, Cory S, et al. Bim: a novel member of the Bcl-2 family that promotes apoptosis. EMBO J. 1998;17:384–395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A, Puthalakath H, Bouillet P, Huang DC, O'Connor L, O'Reilly LA, et al. The role of bim, a proapoptotic BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family in cell-death control. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;917:541–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkers PF, Medema RH, Lammers JW, Koenderman L, Coffer PJ. Expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by the forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander MC, Blumenthal GM, Dennis PA. PTEN loss in the continuum of common cancers, rare syndromes and mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:289–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008;133:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren M, Sittadjody S, Song Z, Samira JL, Burd R, Meuillet EJ. Sodium selenite increases the activity of the tumor suppressor protein, PTEN, in DU-145 prostate cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:322–331. doi: 10.1080/01635580802521338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Sawai H, Ochi N, Matsuo Y, Xu D, Yasuda A, et al. PTEN regulates angiogenesis through PI3K/Akt/VEGF signaling pathway in human pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;331:161–171. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Qu Y, Mao M, Zhang X, Li J, Ferriero D, et al. Involvement of the PTEN-AKT-FOXO3a pathway in neuronal apoptosis in developing rat brain after hypoxia-ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1903–1913. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber EC, Peck B, Delpuech O, Bell GP, East P, Schulze A. FOXO3a regulates reactive oxygen metabolism by inhibiting mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Death Differ. 2011;19:968–979. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SO, Park SJ, Chung AS. Selenite inhibits apoptosis via activation of the PI3-K/Akt pathway. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;973:221–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Guo K, Lu Y. Selenium effectively inhibits 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene-induced apoptosis in human lens epithelial cells through activation of PI3-K/Akt pathway. Mol Vis. 2011;17:2019–2027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan L, Han B, Li J, Li Z, Huang F, Yang Y, et al. Exposure of human leukemia NB4 cells to increasing concentrations of selenite switches the signaling from pro-survival to pro-apoptosis. Ann Hematol. 2009;88:733–742. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.