Abstract

Gga proteins represent a newly recognized, evolutionarily conserved protein family with homology to the “ear” domain of the clathrin adaptor AP-1 γ subunit. Yeast cells contain two Gga proteins, Gga1p and Gga2p, that have been proposed to act in transport between the trans-Golgi network and endosomes. Here we provide genetic and physical evidence that yeast Gga proteins function in trans-Golgi network clathrin coats. Deletion of Gga2p (gga2Δ), the major Gga protein, accentuates growth and α-factor maturation defects in cells carrying a temperature-sensitive allele of the clathrin heavy chain gene. Cells carrying either gga2Δ or a deletion of the AP-1 β subunit gene (apl2Δ) alone are phenotypically normal, but cells carrying both gga2Δ and apl2Δ are defective in growth, α-factor maturation, and transport of carboxypeptidase S to the vacuole. Disruption of both GGA genes and APL2 results in cells so severely compromised in growth that they form only microcolonies. Gga proteins can bind clathrin in vitro and cofractionate with clathrin-coated vesicles. Our results indicate that yeast Gga proteins play an important role in cargo-selective clathrin-mediated protein traffic from the trans-Golgi network to endosomes.

INTRODUCTION

Clathrin-coated vesicles mediate protein transport from the plasma membrane and the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to endosomes. Biogenesis of clathrin-coated vesicles initiates with assembly of clathrin coats on the appropriate organelle membrane, followed by budding and release of clathrin-coated membrane vesicles, then coat disassembly before vesicle docking and fusion to the target membrane (Schmid, 1997). The primary structural constituents of clathrin coats are clathrin and adaptor protein (AP) complexes (reviewed in Hirst and Robinson, 1998; Pishvaee and Payne, 1998; Kirchhausen, 1999). Clathrin is a hexameric complex of heavy and light chains arranged to form three appendages splayed from a central vertex (triskelion). Clathrin triskelia assemble into polyhedral cages that form the outer shell of clathrin coats. AP complexes are heterotetramers that lie between the clathrin shell and the membrane. APs interact with clathrin and other proteins involved in coat assembly, as well as sorting signals on transmembrane cargo proteins (Hirst and Robinson, 1998; Kirchhausen, 1999; Marsh and McMahon, 1999). These interactions presumably allow APs to coordinate coat formation with cargo packaging.

Four AP complexes have been identified in mammalian cells. AP-1 and AP-2 distinguish clathrin-coated vesicles originating from the Golgi complex and the plasma membrane, respectively (Robinson and Pearse, 1986; Robinson, 1987; Ahle et al., 1988). AP-3 plays a role in traffic from the TGN to lysosomes (Cowles et al., 1997a; Dell'Angelica et al., 1997; Simpson et al., 1997; Dell'Angelica et al., 1999b); whether AP-3 functionally interacts with clathrin is unclear (Simpson et al., 1996; Dell'Angelica et al., 1998; Vowels and Payne, 1998). AP-4 does not appear to interact with clathrin but is otherwise functionally uncharacterized (Dell'Angelica et al., 1999a; Hirst et al., 1999). Each AP complex contains two large subunits (γ/α/δ/ε and β1/2/3/4 in AP-1/2/3/4), one medium subunit (μ1–4), and one small subunit (ς1–4) (reviewed in Kirchhausen, 1999). Functions of individual subunits have been analyzed most extensively in the case of the endocytic adaptor AP-2. β2 binds clathrin, appears to interact with other coat components, and is thought to play a direct role in clathrin cage assembly (Gallusser and Kirchhausen, 1993; Owen et al., 2000). The μ2 and possibly the β2 subunits interact with sorting signals in the cytoplasmic domains of transmembrane proteins, thereby collecting appropriate vesicle cargo (Ohno et al., 1995; Owen and Evans, 1998; Rapoport et al., 1998). The α subunit, through a C-terminal “ear” domain, acts to recruit additional factors that facilitate clathrin-coated vesicle formation (Owen et al., 1999; Traub et al., 1999). The roles of AP-1 subunits in TGN clathrin-coated vesicle formation are thought to be generally analogous to those of their AP-2 counterparts at the plasma membrane; however, the functions of AP-1 subunits and the process of TGN clathrin-coated vesicle formation are much less characterized.

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, genetic experiments indicate that clathrin acts in endocytosis and protein sorting from the TGN to endosomes (Seeger and Payne, 1992; Tan et al., 1993; Pishvaee et al., 2000). Three yeast AP complexes, AP-1, AP-2R, and AP-3, are homologous to mammalian AP-1, AP-2, and AP-3. Yeast AP-1 physically interacts with clathrin but AP-2R and AP-3 do not (Yeung et al., 1999; Pishvaee et al., 2000). Consistent with the physical interactions, only AP-1 subunit gene disruptions genetically interact with mutations in the clathrin heavy chain gene (CHC1) (Phan et al., 1994; Rad et al., 1995; Stepp et al., 1995; Panek et al., 1997; Yeung et al., 1999). Combining an AP-1 subunit gene disruption with mutations in CHC1 causes more severe defects in TGN protein sorting than either mutant allele alone, suggesting that AP-1 acts with clathrin at the TGN. In contrast, mutations in AP-2R or AP-3 subunit genes have little or no effect on clathrin-mediated protein transport when present together with chc1 alleles. AP-3 is necessary for protein transport through a clathrin-independent pathway from the TGN to vacuoles that bypasses endosomes (Cowles et al., 1997a; Panek et al., 1997). The role of AP-2R is uncertain. Unexpectedly, in cells expressing wild-type clathrin, complete elimination of the AP-1 complex or disruption of all three AP complexes does not affect clathrin-coated vesicle formation or clathrin-mediated protein transport (Huang et al., 1999; Yeung et al., 1999). These findings suggest the existence of other factors that contribute to clathrin assembly and cargo selection at the TGN in the absence of AP-1.

The recently discovered Gga protein family consists of members with homology to the AP-1 γ subunit (Boman et al., 2000; Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Hirst et al., 2000; Poussu et al., 2000; Takatsu et al., 2000). Gga proteins share a common domain organization. The N-terminal region contains a VHS homology domain related to certain proteins involved in intracellular trafficking and signal transduction (Lohi and Lehto, 1998). The central region contains a domain that binds to the activated form of the small GTPase, ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) (Boman et al., 2000; Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2000; Zhdankina et al., 2001). ARF regulates coat protein recruitment to Golgi membranes (reviewed in Chavrier and Goud, 1999; Donaldson and Jackson, 2000). The C-terminal region of Gga is homologous to the C-terminal ear domain of the AP-1 γ subunit. Mammalian Gga proteins associate with the TGN and adjacent vesicles, but tests for association with clathrin and AP-1 have been negative (Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Hirst et al., 2000). Yeast cells contain two genes encoding Gga proteins, GGA1 and GGA2. Strains lacking both genes display protein sorting defects that implicate Gga1p and Gga2p in protein traffic between the TGN and endosomes (Black and Pelham, 2000; Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Hirst et al., 2000; Zhdankina et al., 2001). Here we present genetic evidence for a functional interaction of yeast Gga proteins with clathrin and AP-1 in protein transport from the TGN to endosomes. We also demonstrate that Gga proteins physically interact with clathrin and are components of clathrin-coated vesicles. Together these results support a model in which Gga proteins and AP-1 both contribute to the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles from the TGN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General Methods and Media

General molecular biology methods were performed as described (Sambrook et al., 1989). Restriction endonucleases were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Unless noted, all reagents were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Monoclonal antibody SKL-1 against yeast clathrin heavy chain is a gift from S. K. Lemmon (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH). Antibodies against Apl1p, Apl2p, Clc1p, and Apl6p have been described previously (Phan et al., 1994; Cowles et al., 1997b; Yeung et al., 1999). Primers used in this study are available on request.

YP medium is 1% Bacto-yeast extract (Difco, Detroit, MI) and 2% Bacto-peptone (Difco). YPD is YP with 2% dextrose. The composition of SD medium is 0.67% of yeast nitrogen base (Difco) and 2% dextrose. Supplemented SD media contains 20 μg/ml histidine, uracil, and tryptophan, and 30 μg/ml leucine, adenine, and lysine. SDYE is supplemented SD plus 0.2% yeast extract. Cell densities were measured by spectrophotometry.

Plasmids and Strains

PCR was used to amplify GGA1 from nucleotides −546 to +2012, where nucleotide +1 represents the beginning of the coding region. PCR amplifications were performed with Klentaq DNA Polymerase (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The PCR product was cloned directly into pCR2.1 TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to create pCR2.1GGA1. The insert of pCR2.1GGA1 was verified by sequencing. Plasmid pCR2.1gga1::TRP1 was created by inserting a blunt-ended fragment containing the TRP1 locus from pBKSTRP1 (Yeung et al., 1999) into pCR2.1GGA1 cleaved with SacII and HindIII and made blunt ended with Klenow DNA Polymerase. To create pGEX-KG-Gga1C, a HincII–XhoI fragment from pCR2.1GGA1 containing sequences corresponding to codons 255–557 of GGA1 was inserted in frame into pGEX-KG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) cleaved with SmaI and XhoI.

Plasmids pKKd28 (vps28Δ::URA3) (Rieder et al., 1996), papl4::TRP1 (Yeung et al., 1999), and YKL560D2, here renamed papl2::URA3 (Rad et al., 1995) have been described previously.

Table 1 lists the strains used in this study. GGA1 and GGA2 were deleted in GPY strains by PCR-based gene replacement with the use of auxotrophic markers from plasmid pRS303 or pRS304 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). YCS150 was created through PCR-generated gga2::KanMX6 and transformation into YCS149 as described (Longtine et al., 1998). Strain YCS149 was generated with the use of an EcoRI fragment from pCR2.1gga1::TRP1 by single-step gene replacement into SEY6210. Similarly, GPY2420 was created with the use of a BstXI fragment from papl2::URA3 into GPY2240, GPY2424 with the use of a KpnI–SacI fragment from papl4::TRP1 into SEY6210, and YCS41 with the use of a BglII–HindIII fragment from pKKd28 into YCS16. The 3 hemaglutinin (HA)-tags for Gga1p and Gga2p were added at the C terminals as described (Longtine et al., 1998). Haploid strains that contain mutations in one or more GGAs in combination with any AP β subunit or AP-1 γ subunit gene deletions were obtained through sporulation of heterozygous diploid strains and tetrad dissections. GPY2420–3C and GPY2420–4D were derived from GPY2420, GPY2422–9D, and GPY2422–11B from GPY2422, GPY2425–15B, and GPY2425–29C from GPY2425, GPY2426–14B, and GPY2426–38C from GPY2426; YCS201 was obtained from a diploid formed by mating YCS150 and YCS41. Gene deletions were checked by PCR or Southern blotting, or both. Expression of HA-tagged forms was checked by immunoblotting. Deletion of VPS28 was assessed by the presence of a class E compartment with the use of the vital dye FM4-64 as described (Rieder et al., 1996).

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SEY6210 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 | (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| SEY6211 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 ade2-101 suc2-Δ9 | (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| YCS16 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 sst1-Δ5 | This study |

| YCS41 | YCS16 vps28Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| TVY614 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 pep4∷LEU2 prb1∷HISG prc1∷HIS3 | (Vida and Emr, 1995) |

| GPY982 | SEY6210 chc1-521 | (Bensen et al., 2000) |

| GPY2149 | SEY6210 gga2Δ∶HIS3 | This study |

| GPY2151 | SEY6210 gga1Δ∷HIS3 | This study |

| YCS149 | SEY6210 gga1Δ∷TRP1 | This study |

| GPY2225 | SEY6211 gga1Δ∷TRP1 | This study |

| GPY2273 | GPY982 gga2Δ∷HIS3 | This study |

| GPY2275 | GPY982 gga1Δ∷HIS3 | This study |

| GPY2385 | GPY6210 gga1Δ∷TRP1 gga2Δ∷HIS3 | This study |

| GPY2276 | GPY6211 gga1Δ∷TRP1 gga2Δ∷HIS3 | This study |

| YCS150 | SEY6210 gga1Δ∷TRP1 gga2Δ∷KANMX6 | This study |

| GPY2373 | GPY6210 GGA2-3HA∷HIS3MX6 | This study |

| GPY2374.2 | GPY6210 GGA1-3HA∷HIS3MX6 | This study |

| GPY2387 | GPY982 GGA2-3HA∷HIS3MX6 | This study |

| GPY2388 | GPY982 GGA1-3HA∷HIS3MX6 | This study |

| GPY2240 | GPY2149 × GPY2225 | This study |

| GPY1783-21D | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 apl1Δ∷LEU2 | (Yeung et al., 1999) |

| GPY1783-25A | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 apl6Δ∷URA3 | (Yeung et al., 1999) |

| GPY2424 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 apl4Δ∷TRP1 | This study |

| GPY2420 | GPY2149 × GPY2225 apl2Δ∷URA3/APL2 | This study |

| GPY2420-3C | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 gga2Δ∷HIS3 apl2Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| GPY2420-4D | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 suc2-Δ9 gga1Δ∷HIS3 apl2Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| GPY2422 | GPY2276 × GPY1783-21D | This study |

| GPY2422-9D | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 suc2-Δ9 gga2Δ∷HIS3 apl1Δ∷LEU2 | This study |

| GPY2422-11B | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 suc2-Δ9 gga1Δ∷TRP1 apl1Δ∷LEU2 | This study |

| GPY2425 | GPY2276 × GPY1783-25A | This study |

| GPY2425-29C | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 suc2-Δ9 gga2Δ∷HIS3 apl6Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| GPY2425-15B | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 suc2-Δ9 gga1Δ∷TRP1 apl6Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| GPY2426 | GPY2276 × GPY2424 | This study |

| GPY2426-14B | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 ade2-101 suc2-Δ9 gga1Δ∷TRP1 gga2Δ∷HIS3 apl4Δ∷TRP1 | This study |

| GPY2426-38C | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 ade2-101 suc2-Δ9 gga2Δ∷HIS3 apl4Δ∷TRP1 | This study |

| YCS201 | YCS150 vps28Δ∷URA3 | This study |

Nondenaturing Immunoprecipitation

Cells were grown to midlogarithmic phase in YPD medium. A total of 5 × 108 of cells were converted to spheroplasts and lysed by resuspension in a final volume of 1 ml of Buffer A (100 mM MES-NaOH, pH 6.5, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM sodium azide, and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 1% Triton X-100 and a protease inhibitor mixture containing 1 μg/ml antipain, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 μg/ml chymostatin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin, and 1 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PIC). The extract was clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 16,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated for 30 min in the presence of IgSorb (The Enzyme Center, Malden, MA), followed by a 20-min centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was brought to 1 ml in lysis buffer and 1 μg of anti-HA antibody (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was added; the samples were incubated for 16 h at 4°C. The antibodies were collected with the use of protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and analyzed by immunoblotting as described (Burnette, 1981), with the use of either goat anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) as a secondary antibody.

Subcellular Fractionation

Cells were grown to midlogarithmic phase in YPD, and a total of 5 × 108 cells were converted to spheroplasts and lysed in 400 μl of Buffer A by agitation with glass beads. The homogenate was sedimented for 5 min at 1500 × g at 4°C, and a low-speed pellet (P1) and supernatant (S1) were obtained. The S1 was subjected to centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 9 min at 4°C, and P2 and S2 were obtained. Finally, S2 was subjected to centrifugation for 17 min at 257,000 × g at 4°C, generating P3 and S3. Equivalent volumes from each fraction were analyzed by immunoblotting. For Sephacryl S-1000 column chromatography, cells were grown to midlogarithmic phase in YPD. A total of 1.2 × 1011 cells were converted to spheroplasts and lysed in Buffer A by agitation with glass beads, processed as described (Chu et al., 1996), and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Metabolic Labeling and Immunoprecipitations

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation of α-factor were performed as described (Yeung et al., 1999), except that the labeling media also contained 10 μg/ml α2-macroglobulin. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was metabolically labeled and immunoprecipitated as described (Seeger and Payne, 1992). For analysis of carboxypeptidase S (CPS), Kex2p, and Vps10p, cell labeling and immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (Cereghino et al., 1995) with the following variations. Log-phase cultures were concentrated to 2 × 107 cells/ml and labeled with 2 μl/1 × 107 cells of Trans 35S label (DuPont NEN, Boston, MA) for 10 min in supplemented SD containing 100 μg/ml BSA and 10 μg/ml α2-macroglobulin. Cells were then incubated with unlabeled 5 mM methionine, 2 mM cysteine, and 0.2% yeast extract for the indicated chase times, and proteins were precipitated with 9% trichloroacetic acid. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with antisera against CPS (Cowles et al., 1997b), Vps10p (Cereghino et al., 1995) or Kex2p (Seeger and Payne, 1992). Endoglycosidase H (DuPont NEN) treatment of radioactive CPS immunoprecipitates was performed as described (Odorizzi et al., 1998). After fluorography, image processing and quantitations were performed with the use of a Molecular Dynamics PhosphoImager (Sunnyvale, CA) using ImageQuant software.

Affinity Chromatography with GST Fusion Proteins

pGEX-KG or pGEX-KG-Gga1C were expressed in XL1-Blue cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and affinity purified with glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). For preparation of yeast extracts, strain TVY614 was grown to midlogarithmic phase in YPD. Cells (5 × 109) were converted to spheroplasts and resuspended at 1 × 109 cells/ml in ice-cold Buffer A containing 1% Triton X-100 and PIC. Cells were further lysed by 30 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer. After centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 30 min, 2 × 109 cell equivalents of the supernatant were applied to glutathione-Sepharose beads carrying either GST alone or GST-Gga1C fusion protein and incubated for 2 h at 4°C with rotation. Beads carrying either GST or GST-Gga1C fusion protein and associated proteins were washed three times with lysis buffer and then eluted in Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) containing 4 M urea. Bound proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Coomasie blue staining and immunoblotting.

RESULTS

Genetic Interactions between GGA Genes and CHC1

As an approach to identify proteins involved in clathrin-mediated transport, we previously performed a screen for mutations that cause severe growth defects in cells carrying a thermosensitive allele of CHC1 (chc1-ts) (Bensen et al., 2000). Among the mutant alleles uncovered in the screen was tcs4, which by itself caused weak defects in TGN protein sorting. A plasmid complementing tcs4 was isolated from a yeast genomic DNA library carried by a centromere-containing vector. Subcloning and sequence analysis revealed GGA2 as the complementing gene (our unpublished results). To characterize genetic interactions among GGA2, the related GGA1, and CHC1, the individual GGA genes were deleted in combination with chc1-ts. For comparison, congenic CHC1 strains containing single or double GGA deletions were also generated. At any of the temperatures tested, single GGA deletions did not cause growth defects (Table 2). Combining gga2Δ with chc1-ts accentuated growth defects caused by chc1-ts at the semipermissive temperature of 30°C and the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C (Table 2). In contrast, gga1Δ together with chc1-ts did not affect growth. The effect on growth of gga1Δ and gga2Δ together was mild at 24 and 30°C, and stronger at 37°C (Table 2). Immunoblot analysis of epitope-tagged versions of Gga1p and Gga2p indicates that Gga1p is expressed at only ∼10–20% of the level of Gga2p (our unpublished results), suggesting that distinct effects of gga1Δ and gga2Δ are likely due to differences in total Gga protein abundance after deletion of single GGA genes rather than functional differences between the Gga proteins.

Table 2.

Growth effects of combining GGA gene deletions and chc1-ts

| 24°C | 30°C | 37°C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| gga1Δ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| gga2Δ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| chc1-ts | +++ | ++ | + |

| chc1-ts gga1Δ | +++ | ++ | + |

| chc1-ts gga2Δ | +++ | + | − |

| gga1Δ gga2Δ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

Cells were streaked onto YPD plates and grown at the indicated temperatures for 2–3 d. The number of + symbols represents relative colony size compared with wild type. For example, ++ represents a colony size of approximately half the diameter of a ++++ colony. No growth is indicated by −.

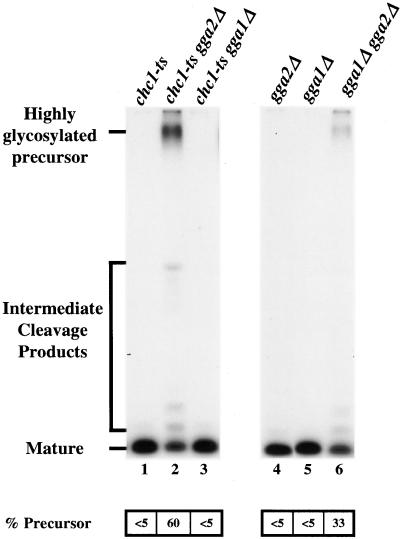

As a test of Gga protein function in clathrin-mediated transport from the TGN, we monitored maturation of the mating pheromone α-factor. Maturation of α-factor precursor is initiated in the TGN by the furin-like protease, Kex2p (Fuller et al., 1988). Kex2p cycles between the TGN and endosomes and optimal localization to the TGN depends on clathrin-dependent sorting to endosomes (reviewed in Conibear and Stevens, 1998). When clathrin is inactivated, Kex2p is mislocalized to the cell surface, resulting in depletion of TGN Kex2p and inefficient maturation of α-factor precursor (Payne and Schekman, 1989; Seeger and Payne, 1992). Thus, the extent of α-factor maturation can serve as a convenient diagnostic for clathrin function in Kex2p localization. To monitor α-factor maturation, cells were labeled with [35S]methionine, and α-factor was immunoprecipitated from the medium. At 24°C, the permissive temperature for chc1-ts, cells harboring gga1Δ, gga2Δ, or chc1-ts secreted fully mature α-factor (Figure 1, lanes 1, 4, and 5). In contrast, a striking defect was apparent in gga2Δ chc1-ts cells (60% highly glycosylated precursor) but not in gga1Δ chc1-ts cells (Figure 1, lanes 2 and 3). The gga1Δ gga2Δ cells secreted 33% of α-factor in the precursor form (Figure 1, lane 6). Accentuation of growth and α-factor maturation defects by gga2Δ when combined with chc1-ts, and the α-factor maturation defect in gga1Δ gga2Δ cells, suggest that Gga proteins participate in clathrin-mediated protein sorting at the TGN.

Figure 1.

Deletion of GGA2 in combination with gga1Δ or chc1-ts affects α-factor maturation. chc1-ts (GPY982; lane 1), chc1-ts gga2Δ (GPY2273; lane 2), chc1-ts gga1Δ (GPY2275; lane 3), gga2Δ (GPY2149; lane 4), gga1Δ (GPY2151; lane 5), and gga1Δ gga2Δ (GPY2385; lane 6) cells were metabolically labeled at 24°C for 45 min, and secreted α-factor was immunoprecipitated from the culture supernatants. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Precursor levels of α-factor were quantified by phosphoimage analysis.

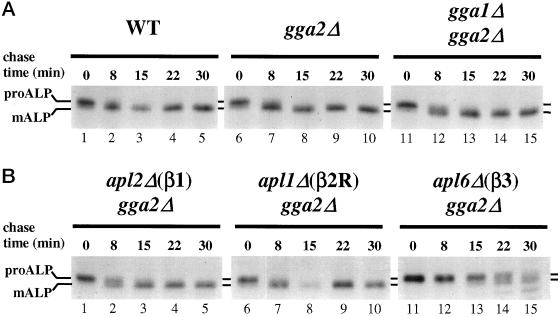

To determine whether the effects of gga mutations are specific for clathrin-dependent protein trafficking from the Golgi complex, we monitored maturation of the vacuolar membrane protein ALP in gga1Δ gga2Δ cells. Precursor ALP (proALP) is normally transported from the Golgi complex to vacuoles via an AP-3–dependent, clathrin-independent pathway (Cowles et al., 1997a; Panek et al., 1997; Vowels and Payne, 1998). Delivery to the vacuole results in proteolytic maturation of proALP to yield a smaller mature ALP form (mALP). Proteolytic maturation of newly synthesized proALP was assessed by pulse–chase immunoprecipitation. ALP maturation was not significantly affected in strains carrying gga1Δ or gga2Δ, or both (Figure 2A). These results indicate that the gga mutations do not have nonspecific pleiotropic effects on protein sorting from the Golgi complex.

Figure 2.

Deletion of GGA2 in combination with gga1Δ or any AP β subunit gene deletion does not affect ALP transport to the vacuole. (A) Wild-type (WT, SEY6210; lanes 1–5), gga2Δ (GPY2149; lanes 6–10), gga1Δ gga2Δ (GPY2385; lanes 11–15) cells. (B) apl2Δ gga2Δ (GPY2420–3C; 1–5), apl1Δ gga2Δ (GPY2422–9D; lanes 6–10), and apl6Δ gga2Δ (GPY2425–29C; lanes 11–15) cells were metabolically labeled for 10 min at 30°C and then subjected to a chase for the indicated times. ALP was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Precursor (proALP) and mature (mALP) forms are indicated.

Genetic Interactions between gga2Δ and AP-1 Gene Deletions

Like gga2Δ, deletions of AP-1 subunits genetically interact with chc1-ts to perturb TGN protein sorting (Phan et al., 1994; Rad et al., 1995; Stepp et al., 1995; Yeung et al., 1999). This similarity prompted us to evaluate the consequences of combining GGA and AP-1 subunit gene deletions. For this purpose, a deletion of the AP-1 β (β1) subunit gene, apl2Δ, was used because previous studies showed that loss of β1 abolishes AP-1 activity (Yeung et al., 1999). To generate haploid strains containing combinations of gga1Δ, gga2Δ, and apl2Δ(β1), a heterozygous diploid strain was induced to undergo meiosis and dissected into tetrads. As controls, the same strategy was used to produce haploids carrying combinations of gga1Δ, gga2Δ, and deletions of either the AP-2R or AP-3 β subunit genes (apl1Δ(β2R) and apl6Δ(β3), respectively). Tetrad analysis revealed that apl2Δ(β1) gga1Δ gga2Δ cells formed only microcolonies, indicating that the absence of AP-1 and Gga proteins severely compromises growth (Table 3). In contrast, gga1Δ gga2Δ tetrad segregants lacking either β2R or β3 were obtained at the expected frequency (Table 3). Although apl2Δ (β1) gga2Δ mutants formed colonies, growth of these strains was impaired (Table 4). None of the other combinations of mutations affected growth except apl6Δ (β3) gga2Δ, which caused a mild growth defect at 37°C (Table 4). These results demonstrate specific interactions between gene deletions eliminating the Gga proteins and the clathrin-associated AP-1 complex.

Table 3.

Segregation analysis of diploid strains heterozygous for GGA and AP β subunit gene deletions

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| apl2Δ (β1) gga1Δ | apl2Δ (β1) gga2Δ | apl2Δ (β1) gga1,2Δ | |

| Expecteda | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Obtaineda | 11 | 8 | 0 ← |

| a 22 tetrads. | |||

| apl1Δ (β2R) gga1Δ | apl1Δ (β2R) gga2Δ | apl1Δ (β2R) gga1,2Δ | |

| Expectedb | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Obtainedb | 17 | 17 | 12 |

| b 34 tetrads. | |||

| apl6Δ (β3) gga1Δ | apl6Δ (β3) gga2Δ | apl6Δ (β3) gga1,2Δ | |

| Expectedc | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Obtainedc | 12 | 17 | 14 |

32 tetrads

Heterozygous strains were sporulated and dissected into tetrads. The expected and actual number of segregants with the indicated genotype is presented. The arrow highlights the observed result that does not correlate with expectations. Expected values were calculated on the basis of the predicted segregation frequencies of each of the three heterozygous markers (0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5).

Table 4.

Growth effects of combining GGA2 and AP β subunit gene deletions

| 24°C | 37°C | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ++++ | ++++ |

| gga2Δ | ++++ | ++++ |

| gga1Δ gga2Δ | +++ | ++ |

| apl2Δ (β1) gga2Δ | ++ | + |

| apl1Δ (β2R) gga2Δ | ++++ | ++++ |

| apl6Δ (β3) gga2Δ | ++++ | +++ |

| apl4Δ (γ) gga2Δ | ++++ | ++++ |

Cells were streaked onto YPD plates and grown at the indicated temperatures for 2–3 d. Relative growth is indicated as described in the legend to Table 2.

Because of the homology between Gga proteins and the AP-1 γ subunit, we also assessed the consequences of combining gga1Δ and gga2Δ with a deletion of the γ subunit gene APL4. In previous studies of genetic interactions between AP-1 subunit genes and chc1-ts, we observed that apl4Δ produced substantially milder defects than apl2Δ (β1) when combined with chc1-ts, suggesting that AP-1 retains a significant function in the absence of the γ subunit (Yeung et al., 1999). Similar results were obtained when apl4Δ was combined with gga2Δ: growth of apl4Δ gga2Δ cells was more robust than apl2Δ (β1) gga2Δ cells (Table 4).

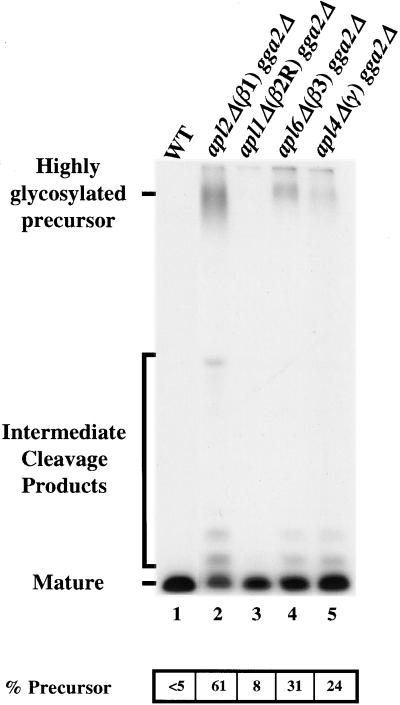

To address whether clathrin-dependent protein sorting at the TGN was affected by combining AP-1 and Gga gene deletions, we assayed α-factor precursor maturation. Figure 3 shows that gga2Δ apl2Δ(β1) cells predominantly secreted precursor (lane 2; 61% of the total α-factor secreted), revealing a strong maturation defect. Lesser defects were apparent in gga2Δ apl6Δ(β3) cells (lane 4; 31% precursor) and gga2Δ apl1Δ(β2R) cells (lane 3; 8% precursor). The level of α-factor precursor secreted from apl4Δ gga2Δ (lane 5; 24% precursor) cells was less than that secreted from the apl2Δ (β1) gga2Δ cells.

Figure 3.

Deletion of the AP-1 β subunit gene in combination with gga2Δ strongly affects α-factor maturation. Wild-type (WT, SEY6210; lane 1), apl2Δ gga2Δ (GPY2420–3C; lane 2), apl1Δ gga2Δ (GPY2422–9D; lane 3), apl6Δ gga2Δ (GPY2425–29C; lane 4), and apl4Δ gga2Δ (GPY2426–38C; lane 5) cells were processed and quantified as described in the legend to Figure 1.

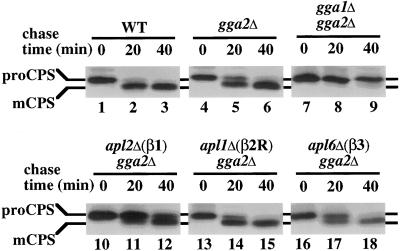

We also analyzed the effects of Gga and AP-1 subunit gene deletions on transport of the vacuolar protease CPS. CPS, an integral membrane protein, is synthesized as an inactive precursor (proCPS) that is transported through the secretory pathway to the TGN, sorted to endosomes, and then delivered to the vacuole where proteolytic maturation yields the active mature form (mCPS) (Cowles et al., 1997b). Like other vacuolar proteins that are sorted from the TGN to endosomes for delivery to the vacuole, CPS maturation is severely affected by clathrin inactivation (B. Yeung, and G. Payne, our unpublished results). By pulse–chase immunoprecipitation, proCPS was completely converted to mature CPS after a 40-min chase period in wild-type cells (Figure 4, lanes 1–3). A mild maturation delay was detected in gga2Δ cells (Figure 4, lanes 4–6). In contrast, the combination of gga1Δ and gga2Δ caused a strong defect in proCPS maturation (Figure 4, lanes 7–9). Of the other deletion combinations, gga2Δ with apl2Δ(β1) resulted in the most significant impairment, with substantial levels of proCPS still present as the precursor form after the chase period (Figure 4, lanes 10–12). The gga2Δ apl6Δ(β3) combination caused a minor maturation delay, and gga2Δ apl1Δ(β2R) had no effect (Figure 4, lanes 13–18).

Figure 4.

Transport of CPS to the vacuole is impaired in gga1Δ gga2Δ and gga2Δ apl2Δ cells. Wild-type (WT, SEY6210; lanes 1–3), gga2Δ (GPY2149; lanes 4–6), gga1Δ gga2Δ (GPY2385; lanes 7–9), apl2Δ gga2Δ (GPY2420–3C; lanes 10–12), apl1Δ gga2Δ (GPY2422–9D; lanes 13–15), and apl6Δ gga2Δ (GPY2425–29C; lanes 16–18) cells were metabolically labeled for 10 min at 30°C and subjected to a chase for the indicated time points. Lysates were prepared and CPS was immunoprecipitated and treated with endoglycosidase H before SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Precursor (proCPS) and the mature forms (mCPS) are indicated.

As a test for specificity of the effects of gga2Δ apl2Δ(β1) on clathrin-mediated traffic, ALP maturation was analyzed. No significant ALP maturation delay was detected in gga2Δ apl2(β1) cells (Figure 2B, lanes 1–5). The same results were obtained with gga2Δ apl1Δ(β2R) cells (Figure 2B, lanes 6–10). By comparison, a clear ALP maturation defect was apparent in the gga2Δ apl6Δ(β3) strain (Figure 2B, lanes 11–15), attributable to the requirement for AP-3 in ALP sorting to the vacuole. These results provide evidence that the combination of gga2Δ and apl2Δ(β1) does not generally perturb transport from the Golgi complex.

Taken together, the specific genetic interactions between gga2Δ and apl2Δ(β1) suggest that Gga proteins and AP-1 both contribute to clathrin-dependent TGN protein sorting.

Gga Proteins Are Required for TGN-to-Endosome Traffic

If Gga proteins are acting in clathrin-dependent protein traffic from the TGN, then gga1Δ gga2Δ cells should be defective in protein transport from the TGN to endosomes. The defects in CPS maturation and Kex2p-mediated α-factor processing reported here, and in vacuolar carboxypeptidase Y sorting reported previously (Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Hirst et al., 2000; Zhdankina et al., 2001), are consistent with impaired TGN-to-endosome traffic but could be due to defects at other steps in traffic within the Golgi–endosome–vacuole system.

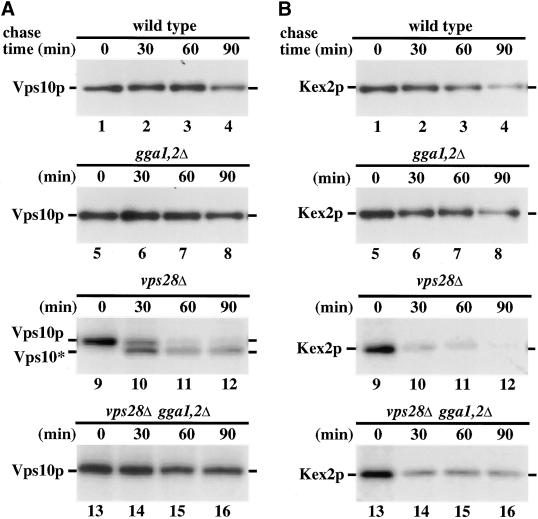

To analyze the TGN-to-endosome pathway more directly, we monitored delivery of Kex2p and Vps10p, the carboxypeptidase Y sorting receptor (Marcusson et al., 1994), to the prevacuolar endosome. For this purpose, we took advantage of the properties of class E vps mutants (Raymond et al., 1992). These mutants are impaired in transport from prevacuolar endosomes, both to the vacuole and to the TGN. Because of this defect, these mutant cells accumulate abnormal endosomal structures that are expanded and proteolytically active (class E compartments). Consequently, TGN proteins such as Vps10p and Kex2p, which normally cycle between the TGN and endosomes, become trapped in class E compartments and are degraded (Cereghino et al., 1995; Piper et al., 1995). Mutations that block transport from the TGN to the endosomal system restore stability to TGN proteins when introduced into a class E vps mutant (Bryant and Stevens, 1997; Seaman et al., 1997). Thus, the role of the Gga proteins in anterograde transport from the TGN was examined with the use of pulse–chase immunoprecipitation to measure the stability of Vps10p and Kex2p in cells containing combinations of the class E vps28Δ allele, gga1Δ and gga2Δ. There was no difference in the stability of Vps10p or Kex2p in wild-type and gga1Δ gga2Δ mutants (Figure 5, A and B, lanes 1–8). This result argues against a specific block in retrieval from endosomes to the TGN in gga1Δ gga2Δ cells because this retrieval pathway is necessary for sorting of TGN proteins away from the pathway to the vacuole (reviewed in Conibear and Stevens, 1998). In vps28Δ cells, both Vps10p and Kex2p were unstable, with half-lives <30 min (Figure 5, A and B, lanes 9–12). In the case of Vps10p, exposure to vacuolar proteases results in formation of a protease-resistant fragment (Figure 5A, lanes 9–12). The presence of gga1Δ and gga2Δ in vps28Δ cells completely stabilized Vps10p (Figure 5A, lanes 13–16). Kex2p was also stabilized in these cells but to a lesser extent (Figure 5B, lanes 13–16). Analysis of the endocytic pathway in triple mutant cells with the vital dye FM4–64 indicated that these cells retained expanded prevacuolar endosomes (our unpublished results), indicating that the gga1Δ gga2Δ combination does not cause TGN protein stabilization by eliminating the class E compartment. These results offer further evidence that Gga1p and Gga2p participate in protein traffic from the TGN to endosomes.

Figure 5.

Deletion of the GGA genes in a class E vps mutant impairs Vps10p and Kex2p transport to endosomes. Wild-type (WT, SEY6210; lanes 1–4), gga1Δ gga2Δ (YCS150; lanes 5–8), vps28Δ (YCS41; lanes 9–12), and vps28Δ gga1Δ gga2Δ (YCS201; lanes 13–16) cells were metabolically labeled for 10 min at 30°C and subjected to a chase for the indicated times. Lysates were prepared and either Vps10p (A) or Kex2p (B) was immunoprecipitated before SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Full-length Kex2p, Vps10p, and the protease-resistant form of Vps10p (Vps10*) are indicated.

Physical Association of Gga Proteins and Clathrin

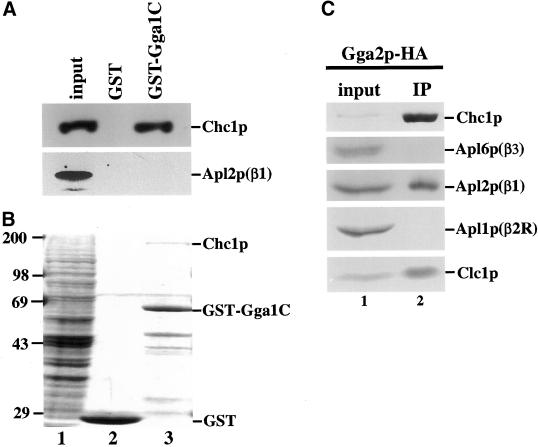

We adopted several strategies to determine whether the genetic interactions described above reflect physical association of Gga proteins with clathrin. GST fusions to the C-terminal regions of the Gga proteins, including the γ ear-related domains, were tested for the ability to bind clathrin and AP-1 in nondenatured cell extracts. Proteins bound to GST fusions or to GST alone were analyzed by both immunoblotting and staining with Coomassie blue. GST-Gga1p bound clathrin but not AP-1 as assayed by immunoblotting (Figure 6A, lane 3). Similar results were obtained with GST-Gga2p (our unpublished results). GST alone did not bind clathrin (Figure 6A, lane 2). Thus, the C-terminal domain of Gga proteins can interact with clathrin independent of the clathrin-binding activity of AP-1. Further support for the specificity of the interaction was obtained by Coomassie blue staining of proteins associated with GST-Gga1p. A single predominant species at the size expected for clathrin heavy chain was apparent in the region of the gel above the GST fusion (Figure 6B, lane 3).

Figure 6.

Interaction of Gga proteins and clathrin in vitro. The C-terminal half of Gga1p (aa 282–585) fused to GST (GST-Gga1C) or GST was bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with extract from TVY614. Proteins bound to GST beads (lane 2) or GST-Gga1C beads (lane 3) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (A) or Coomassie blue staining (B) and compared with extract from TVY614 (input, lane 1). Inputs correspond to 100% (A) or 10% (B) of the amount of extract incubated with beads. (C) Extract from cells expressing Gga2p-3HA (GPY2373; lane 1) was subjected to nondenaturing immunoprecipitation with the use of anti-HA antibodies (IP, lane 2), followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The input corresponds to 2% of the amount of extract subjected to immunoprecipitation.

To analyze interacting proteins by coimmunoprecipitation, influenza HA epitopes were introduced by homologous recombination into the chromosomal GGA2 gene to generate a functional Gga2p protein tagged at the C terminus. Gga2p-HA was immunoprecipitated from whole-cell extracts solubilized with Triton X-100, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting for clathrin and the β subunits of AP complexes. As shown in Figure 6C, both clathrin heavy and light chains were coprecipitated with Gga2p-HA, providing further support for physical association of Gga2p and clathrin. AP-1, but not AP-2R or AP-3, was also coprecipitated; however, a similar experiment with the use of a sample prepared by mixing extracts from Gga2p-HA apl2Δ cells and gga2Δ cells revealed that an equivalent level of AP-1 interaction with Gga2p can occur after lysis (perhaps by assembly into preexisting coats; our unpublished results). Thus, these experiments show that clathrin, Gga proteins, and AP-1 can associate in a specific manner in vitro.

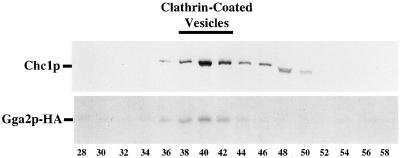

The interaction of Gga proteins with clathrin and AP-1 suggested that Gga proteins could be components of clathrin-coated vesicles. To evaluate this possibility, cell extracts were subjected to differential centrifugation and gel filtration chromatography of a high-speed pellet to generate fractions enriched for clathrin-coated vesicles. In fractions from differential centrifugation, the majority of Gga2p-HA associated with medium speed and high speed pellets (P2 and P3), but significant levels were also detected in the high-speed supernatant (our unpublished results). Chromatography of a P3 fraction through Sephacryl S-1000 revealed peak levels of Gga2p-HA (and Gga1p-HA; our unpublished results) in clathrin-coated vesicle fractions 38–42 (Figure 7), providing strong evidence for incorporation of Gga proteins into vesicular clathrin coats.

Figure 7.

Gga2p cofractionates with clathrin-coated vesicles. Shown is an S-1000 column chromatography elution profile of a high-speed pellet fractionation (60 min, 100,000 × g) from Gga2p-HA–expressing cells (GPY2373). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies against Chc1p and HA.

DISCUSSION

We have identified GGA2 in a screen for mutations that accentuate growth defects caused by chc1-ts (Bensen et al., 2000) and characterized genetic and physical interactions between yeast Gga proteins and components of clathrin coats. Our results demonstrate that combining mutant alleles of GGA genes, CHC1, and AP-1 subunit genes accentuates growth and TGN protein sorting defects compared with single alleles. In addition, Gga proteins physically interact with clathrin and AP-1 in vitro and are components of clathrin-coated vesicles. Finally, elimination of Gga proteins impedes transport of TGN proteins to endosomes. These results indicate that Gga proteins function with clathrin in protein sorting from the TGN.

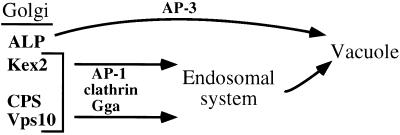

In otherwise wild-type yeast cells, AP-1 is not required for clathrin-mediated protein transport or clathrin-coated vesicle formation, although it is the only clathrin-interacting AP in yeast (Huang et al., 1999; Yeung et al., 1999). The severe growth defect of cells lacking functional AP-1 and both Gga proteins argues that functions supplied by Gga proteins account for AP-1 dispensability. In principal, this type of genetic redundancy could be due to AP-1 and the Gga proteins functioning in separate pathways or providing overlapping functions in the same pathway(s) (Guarente, 1993). A recent report has invoked function in separate pathways, with AP-1 acting in traffic from the TGN to early endosomes and Gga proteins in traffic from the TGN to prevacuolar endosomes (Black and Pelham, 2000). Our results are generally consistent with the possibility that AP-1 and Gga proteins are present on distinct clathrin-coated vesicles (Figure 8). Cells lacking Gga proteins (but expressing AP-1) exhibit a more severe CPS maturation defect than cells lacking Gga2p and β1 (but expressing Gga1p), suggesting that Gga1p is more important than AP-1 in CPS sorting to endosomes. We observed similar mutant effects on Vps10p-mediated sorting of carboxypeptidase Y, which has been suggested to occur primarily from the TGN to prevacuolar endosomes (our unpublished results). Conversely, cells lacking Gga2p and β1 display a stronger α-factor maturation defect than cells lacking Gga1p and Gga2p, suggesting that AP-1 function is more critical than Gga1p for Kex2p sorting. This result could be explained by an AP-1-dependent pathway that is primarily responsible for directing Kex2p to endosomes. In further support of a differential role for Gga proteins in TGN-to-endosomal sorting, eliminating the Gga proteins in a class E vps mutant blocks transport of Vps10p from the TGN to endosomes more completely than Kex2p. Function of Gga proteins and AP-1 in mostly separate pathways would also be consistent with the small degree of colocalization between mammalian Gga proteins and AP-1 (Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Hirst et al., 2000).

Figure 8.

Gga proteins and AP-1 act with clathrin in Golgi-to-endosome transport. In this model, Kex2p, CPS, and Vps10p are packaged into clathrin-coated vesicles for transport to endosomes. ALP is sorted into AP-3–dependent, clathrin-independent vesicles for transport directly to the vacuole. The two arrows leading to the endosomal system signify the possibilities that AP-1 and Gga proteins act in separate clathrin-dependent pathways or act in the same clathrin-dependent pathway but exhibit different cargo selectivities. See DISCUSSION for details.

An alternative possibility is that AP-1 and Gga proteins function together in clathrin coats, but with different cargo selectivity (Figure 8). Coimmunoprecipitation of AP-1 and clathrin with Gga proteins indicates that AP-1 and Gga proteins have the potential to associate in a common complex. The association appears to be specific because neither AP-2R nor AP-3 nor other clathrin-interacting proteins Ent2p and AP-180 (Wendland and Emr, 1998; Wendland et al., 1999) were coprecipitated (Figure 6C; and our unpublished results); however, further analysis will be required to determine whether these proteins act together in the same clathrin coats in vivo.

Cells carrying gga2Δ and a deletion of the AP-3 β subunit displayed detectable α-factor and CPS maturation defects. Several factors make a case that these phenotypes do not reflect a significant role for Gga2p in AP-3–mediated transport. First, ALP transport through the AP-3–dependent Golgi to vacuole pathway is not affected in gga1Δ gga2Δ cells. Second, Gga proteins are not physically associated with AP-3 by coimmunoprecipitation. Third, mutations in AP-3 do not affect the TGN-to-endosome transport pathway involved in Kex2p localization (Cowles et al., 1997a; Panek et al., 1997). Thus, it is likely that the α-factor and CPS maturation defects in gga2Δ apl6Δ(β3) cells are indirect effects of perturbing independent pathways using either AP-3 or Gga proteins. Nevertheless, our data do not exclude the possibility that Gga proteins act in other clathrin-independent transport steps. The severe growth defect in apl2Δ gga1Δ gga2Δ cells is consistent with this possibility.

Regardless of the basis for the genetic redundancy between Gga proteins and AP-1, the structural relationship between Gga C-terminal domains and the AP-1 γ subunit ear argues for some degree of functional similarity (Hirst et al., 2000; Takatsu et al., 2000). In assessing this hypothesis, we observed that deletion of the γ gene was not as detrimental as deletion of the β1 gene when combined with gga2Δ. Because loss of β1 but not loss of γ abolishes AP-1 function (Yeung et al., 1999), gga2Δ cells lacking γ retain some level of AP-1 activity. Consequently, the less severe effects of eliminating γ compared with β1 in gga2Δ cells implies that AP-1 subunits other than γ can partially compensate for the absence of Gga proteins. Our results therefore suggest that AP-1 shares functions with Gga proteins that extend beyond the γ subunit.

One likely common function of AP-1 and Gga proteins is clathrin coat assembly, given the shared ability to bind to clathrin. The mammalian AP-1 β subunit is thought to be a critical factor in coat assembly activity because it directly binds clathrin and stimulates in vitro assembly of clathrin coats (Gallusser and Kirchhausen, 1993); however, the requirement for β in assembly has not been specifically addressed in vivo, leaving open the possibility that other coat components can provide assembly activity. In yeast AP-1, both the β and γ subunits can independently bind clathrin (B. Yeung and G. Payne, unpublished observations). The β subunit contains clathrin binding motifs (L L/I D/E/N L/F D/E)], termed clathrin boxes, that in mammalian proteins have been shown to directly bind the N-terminal domain of clathrin heavy chain (Dell'Angelica et al., 1998; ter Haar et al., 2000). The γ subunit likely binds clathrin indirectly by recruiting accessory factors containing the clathrin binding motif, in analogy to the mammalian AP-2 α subunit (Owen et al., 1999; Traub et al., 1999). Our data show that yeast Gga proteins can bind clathrin independently of AP-1. It is worth noting that yeast Gga1p contains two clathrin boxes, and Gga2p contains six related clathrin binding motifs (D/SLL) (Morgan et al., 2000) that could allow direct binding. Considering the multiple clathrin binding activities of AP-1 and Gga proteins, we propose that functional redundancy in clathrin assembly activity accounts for the absence of trafficking phenotypes in cells lacking AP-1, Gga1p, or Gga2p and the exacerbated phenotypes in cells lacking combinations of these proteins.

In further support for Gga protein involvement in coat assembly, mammalian Gga proteins are effectors of the GTP-activated form of ARF, a central factor in recruitment of AP-1 to membranes and nucleation of TGN clathrin coats (Boman et al., 2000; Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2000). In yeast, ARF has been implicated in clathrin function by genetic interaction studies (Chen and Graham, 1998), and yeast Gga proteins, like their mammalian counterparts, bind activated ARF (Zhu et al., 2000; Zhdankina et al., 2001). Furthermore, Gga localization, which is punctate in wild-type cells, becomes diffuse in cells lacking the predominant ARF, Arf1p (our unpublished results). These observations indicate that yeast Gga proteins, like their mammalian counterparts, are also ARF effectors. Our results do not support a model in which ARF acts through Gga proteins to recruit AP-1 to Golgi membranes. The synthetic genetic interactions between deletions of GGA and AP-1 subunit genes are not consistent with a simple sequential pathway from activated ARF to Gga proteins to AP-1. Additionally, by subcellular fractionation, we did not observe a change in AP-1 distribution during deletion of the GGA genes (our unpublished results).

The strong association of yeast Gga proteins with clathrin appears to be at variance with results from analysis of mammalian Gga proteins. Mammalian Gga proteins did not copurify with clathrin-coated vesicles and were not clearly colocalized with AP-1 by immunofluorescence (Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; Hirst et al., 2000); however, it is possible that mammalian Gga protein association with clathrin-coated vesicles is more labile than that of the yeast proteins. A potential example of this difference can be found in results from differential centrifugation experiments in which mammalian Gga proteins are mostly soluble and yeast Gga proteins are mostly sedimentable (Dell'Angelica et al., 2000; our unpublished results). Although mammalian and yeast Gga proteins could function differently, the high degree of similarity, which includes conserved structures, presence of clathrin binding motifs, interactions with ARF, and function at the TGN, leads us to favor the hypothesis that mammalian Gga proteins also function with clathrin at the TGN. In this scenario, the evolutionarily conserved Gga proteins are likely to play a critical, previously unrecognized role in the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles at the TGN (Figure 8).

Note added in proof. Very recently it has been shown that mammalian Gga proteins interact with clathrin. Puertollano, R., Randazzo, P.A., Presley, J.F., Hartnell, L.M., and Bonifacino, J.S. (2001). The GGAs promote ARF-dependent recruitment of clathrin to the TGN. Cell 105, 93–102.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Todd Lorenz for technical help and Babak Pishvaee for comments on this manuscript. We also thank Jennifer Hirst and Annette Boman for communicating unpublished results. C.J.S. is a fellow of the American Cancer Society supported by the Holland Peck Charitable Fund. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM39040 (G.S.P) and CA58689 (S.D.E.). S.D.E. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- Ahle S, Mann A, Eichelsbacher U, Ungewickell E. Structural relationships between clathrin assembly proteins from the Golgi and the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 1988;7:919–929. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensen ES, Costaguta G, Payne GS. Synthetic genetic interactions with temperature-sensitive clathrin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Roles for synaptojanin-like Inp53p and dynamin-related Vps1p in clathrin-dependent protein sorting at the trans-Golgi network. Genetics. 2000;154:83–97. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MW, Pelham HR. A selective transport route from golgi to late endosomes that requires the yeast GGA proteins. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:587–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman AL, Zhang C, Zhu X, Kahn RA. A family of ADP-ribosylation factor effectors that can alter membrane transport through the trans-Golgi. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1241–1255. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.4.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant NJ, Stevens TH. Two separate signals act independently to localize a yeast late Golgi membrane protein through a combination of retrieval and retention. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:287–297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette WN. “Western blotting”: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghino JL, Marcusson EG, Emr SD. The cytoplasmic tail domain of the vacuolar protein sorting receptor Vps10p and a subset of VPS gene products regulate receptor stability, function, and localization. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1089–1102. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.9.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavrier P, Goud B. The role of ARF and Rab GTPases in membrane transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:466–475. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Graham TR. An arf1Delta synthetic lethal screen identifies a new clathrin heavy chain conditional allele that perturbs vacuolar protein transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1998;150:577–589. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DS, Pishvaee B, Payne GS. The light chain subunit is required for clathrin function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33123–33130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conibear E, Stevens TH. Multiple sorting pathways between the late Golgi and the vacuole in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404:211–230. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles CR, Odorizzi G, Payne GS, Emr SD. The AP-3 adaptor complex is essential for cargo-selective transport to the yeast vacuole. Cell. 1997a;91:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles CR, Snyder WB, Burd CG, Emr SD. Novel Golgi to vacuole delivery pathway in yeast: identification of a sorting determinant and required transport component. EMBO J. 1997b;16:2769–2782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC, Klumperman J, Stoorvogel W, Bonifacino JS. Association of the AP-3 adaptor complex with clathrin. Science. 1998;280:431–434. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC, Mullins C, Bonifacino JS. AP-4, a novel protein complex related to clathrin adaptors. J Biol Chem. 1999a;274:7278–7285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC, Ohno H, Ooi CE, Rabinovich E, Roche KW, Bonifacino JS. AP-3: an adaptor-like protein complex with ubiquitous expression. EMBO J. 1997;16:917–928. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC, Puertollano R, Mullins C, Aguilar RC, Vargas JD, Hartnell LM, Bonifacino JS. GGAs: a family of ADP ribosylation factor-binding proteins related to adaptors and associated with the Golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:81–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC, Shotelersuk V, Aguilar RC, Gahl WA, Bonifacino JS. Altered trafficking of lysosomal proteins in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome due to mutations in the beta 3A subunit of the AP-3 adaptor. Mol Cell. 1999b;3:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JG, Jackson CL. Regulators and effectors of the ARF GTPases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:475–482. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RS, Sterne RE, Thorner J. Enzymes required for yeast prohormone processing. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:345–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallusser A, Kirchhausen T. The beta 1 and beta 2 subunits of the AP complexes are the clathrin coat assembly components. EMBO J. 1993;12:5237–5244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L. Synthetic enhancement in gene interaction: a genetic tool come of age. Trends Genet. 1993;9:362–366. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90042-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J, Bright NA, Rous B, Robinson MS. Characterization of a fourth adaptor-related protein complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2787–2802. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J, Lui WW, Bright NA, Totty N, Seaman MN, Robinson MS. A family of proteins with gamma-adaptin and VHS domains that facilitate trafficking between the trans-Golgi network and the vacuole/lysosome. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:67–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J, Robinson MS. Clathrin and adaptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404:173–193. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang KM, D'Hondt K, Riezman H, Lemmon SK. Clathrin functions in the absence of heterotetrameric adaptors and AP180-related proteins in yeast. EMBO J. 1999;18:3897–3908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhausen T. Adaptors for clathrin-mediated traffic. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:705–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohi O, Lehto VP. VHS domain marks a group of proteins involved in endocytosis and vesicular trafficking. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:255–257. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie III A, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcusson EG, Horazdovsky BF, Cereghino JL, Gharakhanian E, Emr SD. The sorting receptor for yeast vacuolar carboxypeptidase Y is encoded by the VPS10 gene. Cell. 1994;77:579–586. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh M, McMahon HT. The structural era of endocytosis. Science. 1999;285:215–220. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JR, Prasad K, Hao W, Augustine GJ, Lafer EM. A conserved clathrin assembly motif essential for synaptic vesicle endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8667–8676. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08667.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi G, Babst M, Emr SD. Fab1p PtdIns(3)P 5-kinase function essential for protein sorting in the multivesicular body. Cell. 1998;95:847–858. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H, Stewart J, Fournier MC, Bosshart H, Rhee I, Miyatake S, Saito T, Gallusser A, Kirchhausen T, Bonifacino JS. Interaction of tyrosine-based sorting signals with clathrin-associated proteins. Science. 1995;269:1872–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.7569928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen DJ, Evans PR. A structural explanation for the recognition of tyrosine-based endocytotic signals. Science. 1998;282:1327–1332. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen DJ, Vallis Y, Noble ME, Hunter JB, Dafforn TR, Evans PR, McMahon HT. A structural explanation for the binding of multiple ligands by the alpha-adaptin appendage domain. Cell. 1999;97:805–815. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80791-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen DJ, Vallis Y, Pearse BM, McMahon HT, Evans PR. The structure and function of the beta2-adaptin appendage domain. EMBO J. 2000;19:4216–4227. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panek HR, Stepp JD, Engle HM, Marks KM, Tan PK, Lemmon SK, Robinson LC. Suppressors of YCK-encoded yeast casein kinase 1 deficiency define the four subunits of a novel clathrin AP-like complex. EMBO J. 1997;16:4194–4204. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne GS, Schekman R. Clathrin: a role in the intracellular retention of a Golgi membrane protein. Science. 1989;245:1358–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.2675311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan HL, Finlay JA, Chu DS, Tan PK, Kirchhausen T, Payne GS. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae APS1 gene encodes a homolog of the small subunit of the mammalian clathrin AP-1 complex: evidence for functional interaction with clathrin at the Golgi complex. EMBO J. 1994;13:1706–1717. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper RC, Cooper AA, Yang H, Stevens TH. VPS27 controls vacuolar and endocytic traffic through a prevacuolar compartment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:603–617. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishvaee B, Costaguta G, Yeung BG, Ryazantsev S, Greener T, Greene LE, Eisenberg E, McCaffery JM, Payne GS. A yeast DNA J protein required for uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:958–963. doi: 10.1038/35046619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishvaee B, Payne GS. Clathrin coats—threads laid bare. Cell. 1998;95:443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poussu A, Lohi O, Lehto VP. Vear, a novel Golgi-associated protein with VHS and gamma-adaptin “ear” domains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7176–7183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rad MR, Phan HL, Kirchrath L, Tan PK, Kirchhausen T, Hollenberg CP, Payne GS. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Apl2p, a homologue of the mammalian clathrin AP beta subunit, plays a role in clathrin-dependent Golgi functions. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1605–1615. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport I, Chen YC, Cupers P, Shoelson SE, Kirchhausen T. Dileucine-based sorting signals bind to the beta chain of AP-1 at a site distinct and regulated differently from the tyrosine-based motif- binding site. EMBO J. 1998;17:2148–2155. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CK, Howald-Stevenson I, Vater CA, Stevens TH. Morphological classification of the yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants: evidence for a prevacuolar compartment in class E vps mutants. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1389–1402. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.12.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder SE, Banta LM, Kohrer K, McCaffery JM, Emr SD. Multilamellar endosome-like compartment accumulates in the yeast vps28 vacuolar protein sorting mutant. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:985–999. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JS, Klionsky DJ, Banta LM, Emr SD. Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4936–4948. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS. 100-kD coated vesicle proteins: molecular heterogeneity and intracellular distribution studied with monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:887–895. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS, Pearse BM. Immunofluorescent localization of 100K coated vesicle proteins. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:48–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Maniatis T, Fritsch EF. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid SL. Clathrin-coated vesicle formation and protein sorting: an integrated process. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:511–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MN, Marcusson EG, Cereghino JL, Emr SD. Endosome to Golgi retrieval of the vacuolar protein sorting receptor, Vps10p, requires the function of the VPS29, VPS30, and VPS35 gene products. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:79–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M, Payne GS. Selective and immediate effects of clathrin heavy chain mutations on Golgi membrane protein retention in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:531–540. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.3.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson F, Bright NA, West MA, Newman LS, Darnell RB, Robinson MS. A novel adaptor-related protein complex. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:749–760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson F, Peden AA, Christopoulou L, Robinson MS. Characterization of the adaptor-related protein complex, AP-3. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:835–845. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.4.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp JD, Pellicena-Palle A, Hamilton S, Kirchhausen T, Lemmon SK. A late Golgi sorting function for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Apm1p, but not for Apm2p, a second yeast clathrin AP medium chain-related protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:41–58. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatsu H, Yoshino K, Nakayama K. Adaptor gamma ear homology domain conserved in gamma-adaptin and GGA proteins that interact with gamma-synergin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:719–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan PK, Davis NG, Sprague GF, Payne GS. Clathrin facilitates the internalization of seven transmembrane segment receptors for mating pheromones in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1707–1716. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Haar E, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T. Peptide-in-groove interactions link target proteins to the beta- propeller of clathrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1096–1100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub LM, Downs MA, Westrich JL, Fremont DH. Crystal structure of the alpha appendage of AP-2 reveals a recruitment platform for clathrin-coat assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8907–8912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida TA, Emr SD. A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:779–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vowels JJ, Payne GS. A dileucine-like sorting signal directs transport into an AP-3- dependent, clathrin-independent pathway to the yeast vacuole. EMBO J. 1998;17:2482–2493. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland B, Emr SD. Pan1p, yeast eps15, functions as a multivalent adaptor that coordinates protein-protein interactions essential for endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:71–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland B, Steece KE, Emr SD. Yeast epsins contain an essential N-terminal ENTH domain, bind clathrin and are required for endocytosis. EMBO J. 1999;18:4383–4393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung BG, Phan HL, Payne GS. Adaptor complex-independent clathrin function in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3643–3659. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhdankina O, Strand NL, Redmond JM, Boman AL. Yeast GGA proteins interact with GTP-bound Arf and facilitate transport through the Golgi. Yeast. 2001;18:1–18. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200101)18:1<1::AID-YEA644>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Boman AL, Kuai J, Cieplak W, Kahn RA. Effectors increase the affinity of ADP-ribosylation factor for GTP to increase binding. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13465–13475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]