Abstract

Background:

Strong working relationships between pharmacists and physicians are needed to optimize patient care. Understanding attitudes and barriers to collaboration between pharmacists and physicians may help with delivery of primary health care services. The objective of this study was to capture the opinions of family physicians and community pharmacists in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) regarding collaborative practice.

Methods:

Two parallel surveys were offered to all community pharmacists and family physicians in NL. Surveys assessed the following: attitudes and experience with collaborative practice, preferred communication methods, perceived role of pharmacists, areas for more collaboration and barriers to collaborative practice. Results for both groups were analyzed separately, with comparisons between groups to compare responses with similar questions.

Results:

Survey response rates were 78.6% and 7.1% for pharmacists and physicians, respectively. Both groups overwhelmingly agreed that collaborative practice could result in improved patient outcomes and agreed that major barriers were lack of time and compensation and the need to deal with multiple pharmacists/physicians. Physicians indicated they would like more collaboration for insurance approvals and patient counselling, while pharmacists want to assist with identifying and managing patients’ drug-related problems. Both groups want more collaboration to improve patient adherence.

Conclusion:

Both groups agree that collaborative practice can positively affect patient outcomes and would like more collaboration opportunities. However, physicians and pharmacists disagree about the areas where they would like to collaborate to deliver care. Changes to reimbursement models and infrastructure are needed to facilitate enhanced collaboration between pharmacists and physicians in the community setting.

Knowledge Into Practice.

Community pharmacists and family physicians agree that collaborative practice can optimize patient outcomes and would like to collaborate more.

Physicians and pharmacists have differing opinions regarding the role of the community pharmacist, as reflected by the areas in which they would like to collaborate. Physicians would like to collaborate to improve patient adherence and for support in insurance approvals, while pharmacists would like to provide more support in identifying and managing patients’ drug-related problems.

Physicians and pharmacists agree that major barriers to collaboration include lack of compensation, insufficient time and the need to collaborate with multiple pharmacists/physicians to provide care to patients.

Future research is warranted to gather the impact of changes to the pharmacist scope of practice on collaboration.

Mise En Connaissance En Pratique.

Les pharmaciens communautaires et les médecins de famille s’entendent sur le fait que la collaboration interprofessionnelle permet d’améliorer l’état de santé des patients et souhaitent une collaboration accrue.

Les médecins et les pharmaciens ont des perceptions différentes du rôle du pharmacien communautaire. Leurs opinions divergent quant aux types d’interventions pour lesquelles ils seraient prêts à collaborer. Les médecins souhaiteraient collaborer pour améliorer l’adhésion au traitement et pour favoriser la prise en charge des assurances, alors que les pharmaciens souhaiteraient participer davantage à la détection et à la gestion des problèmes reliés à la pharmacothérapie.

Les médecins et les pharmaciens sont d’avis que les principaux obstacles à la collaboration incluent l’absence de rémunération, le manque de temps et la nécessité de collaborer avec plusieurs pharmaciens ou médecins pour la prestation de soins aux patients.

D’autres études sont nécessaires pour mieux comprendre l’influence de l’élargissement du champ de pratique des pharmaciens sur la collaboration interprofessionnelle.

Introduction

The primary role of the pharmacist is evolving from a focus on dispensing medications to taking increased responsibility for and facilitating optimal medication use through collaboration.1 The increasing complexity of medication therapies underscores the need for strong working relationships between pharmacists and physicians to optimize patient care. The organized structure of institutional settings facilitates communication and collaboration between health care professionals. Hospital pharmacists have demonstrated their ability to improve care by decreasing mortality and morbidity, reducing adverse drug events and reducing health care costs.2,3 However, collaborative practice in the community is more challenging.

Community pharmacists can improve patient care in a variety of ways, including medication management, patient counselling and health professional education.4 Unfortunately, the silos in which pharmacists practise act as barriers to collaboration. Few Canadian studies have examined the collaborative relationship between community pharmacists and physicians in the provision of patient care.5-8 Ontario pharmacists and physicians were found to have differing opinions regarding appropriate roles for pharmacists, and there was a recognized need to clarify professional roles, identify efficient ways to communicate and determine compensation mechanisms to enhance collaboration.5,6 A Saskatchewan study solicited opinions from family physicians about increased collaboration with community pharmacists to increase patient adherence.7 Although most agreed that more collaboration would improve adherence, barriers identified included time commitments and financial reimbursement.

Understanding attitudes and barriers to collaboration between community pharmacists and family physicians may further optimize delivery of primary health care services. The objective of this study was to capture the opinions of family physicians and community pharmacists in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) regarding collaborative approaches to patient care.

Methods

A literature search was conducted to identify published works regarding collaborative practice between pharmacists and physicians in community settings, to inform the development of survey questions.9-16 Based on the literature and the questions of interest from the research team, 2 original surveys were developed, one for pharmacists and one for physicians. Each survey consisted of 6 themes. Where possible, the same questions were asked of each group. For 5 of the themes, both groups were asked the same questions to determine attitudes regarding collaborative practice, personal experience with collaborative practice, preferred methods of communication, areas where more collaboration is desired and barriers to collaborative practice. A final theme was related to the perceived role of community pharmacists. In this section, pharmacists were asked their level of agreement with statements about specific roles or duties of pharmacists. Physicians were asked to rank the same list of roles or duties in order of importance. Demographic information about respondents was also collected. The pharmacist and physician surveys were piloted with groups of community pharmacists and family physicians, respectively, and revised for clarity and to improve face validity prior to being submitted for ethics approval.

Formal collaborative practice arrangements or agreements were not required in order for pharmacists and physicians to participate in the study. We did not identify a standard definition of collaborative practice from the literature that met the needs of this project. Therefore, for consistency purposes, we defined collaborative practice as follows: “Family doctors and community pharmacists sharing information and working together to improve health care delivery for a specific patient.” The study received approval from the Human Investigations Committee at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Pharmacist survey

All community pharmacists licensed in NL and working in either hospital or community pharmacy, as identified through the provincial registry on the NL Pharmacy Board website, were invited to participate. Community pharmacists were called at their place of work and invited to participate. If they agreed, they were able to complete the survey at the time of the call or at an agreed upon convenient time. Hospital pharmacists were sent a letter inviting them to participate. If they met the eligibility criteria of having worked in a community pharmacy within the previous 12 months and were interested in participating, they were directed to call one of the telephone interviewers to complete the survey.

During November 2007, trained callers administered the survey. A computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) technique was used by the callers to record data in real time directly into an MS Access database.

Physician survey

The most appropriate method to survey physicians was chosen in consultation with the NL Medical Association (NLMA). During the first week of January 2008, all family physicians in NL were sent an e-mail with a link to complete the online survey (via SurveyMonkey) or were mailed a paper survey, according to their preferred means of corresponding with the NLMA. A reminder was sent 2 weeks after the first mailing to optimize response rates. Responses were collected up to the end of January 2008.

Data analysis

Most survey responses were scored using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. For these questions, responses were collapsed to 3 categories of agree (included strongly agree and agree), neutral and disagree (included strongly disagree and disagree) and reported as percentage of agreement or disagreement for each statement. One question on the physician survey asked respondents to rank a series of pharmacist functions in order of their ability to significantly improve patient care. These data were analyzed by the frequency with which each function was considered to be among the top 3 most important functions. Data were entered into SPSS (version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, Illinois), and descriptive statistics were used to compile the results for each group separately.

Results

Of 518 pharmacists invited to participate, 407 surveys were completed for a response rate of 78.6%. For the physician survey, 33 of the 462 (7.1%) family doctors invited completed the survey.

Respondents to both surveys were similar in demographics, although the proportion of recent graduates (<10 years since graduation) was higher for the pharmacist group (Table 1). There was similar distribution in both groups among those who practised in smaller vs larger communities.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | Pharmacist respondents* (n = 407), n (%) | Physician respondents* (n = 33), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 195 (47.9) | 12 (36.4) |

| Age, y | ||

| 20-29 | 64 (15.7) | – |

| 30-39 | 109 (26.8) | 10 (30.3) |

| 40-49 | 134 (32.9) | 9 (27.3) |

| ≥50 | 95 (23.3) | 11 (33.3) |

| Number of years since graduation | ||

| <10 | 122 (30) | 4 (12.1) |

| 10-19 | 88 (21.6) | 11 (33.3) |

| 20-29 | 128 (31.4) | 8 (24.2) |

| ≥30 | 66 (16.2) | 7 (21.2) |

| Community size | ||

| Rural area (<2000) | 38 (9.3) | 4 (12.1) |

| Small town (2000–10,000) | 167 (41) | 11 (33.3) |

| City (>10,000) | 201 (49.4) | 15 (45.5) |

Not all respondents answered each question.

Forty-five percent of pharmacists reported practising in an independent pharmacy setting, while the remainder worked for banner (14%), supermarket (24%) or chain (17%) pharmacies. Two-thirds of physicians indicated they practised in a multiphysician practice. Approximately 50% of pharmacists and 41% of physicians self-declared an academic affiliation with Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Attitudes and experience with collaborative practice

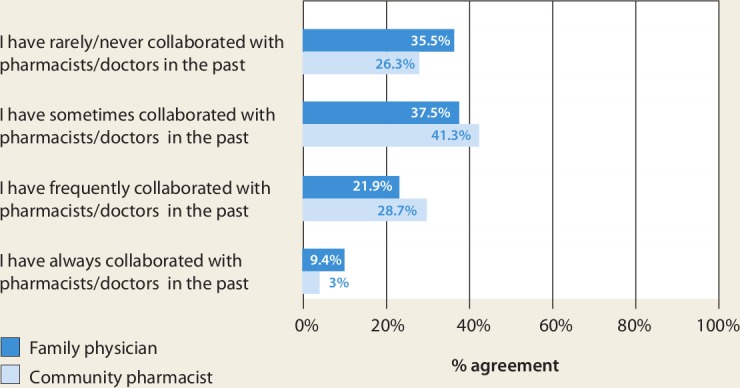

Pharmacists and physicians agreed that collaborative practice can result in improved health outcomes for patients (Figure 1); however, this was not a routine part of their practice. While most pharmacists and physicians reported collaborating in the past, more than one-third of physicians and one-quarter of pharmacists have never or rarely practised collaboratively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Attitudes toward collaborative practice

Figure 2.

Experience with collaborative practice

Preferred methods of communication

Regarding sharing patient information, pharmacists preferred telephone or face-to-face communication over fax or paper correspondence with physicians. Physicians preferred telephone or fax communication (Figure 3). Fifty-eight percent of pharmacists believed that electronic transfer of information should be explored.

Figure 3.

Preferred methods of communication for collaborative practice

Perceptions of the pharmacists’ role

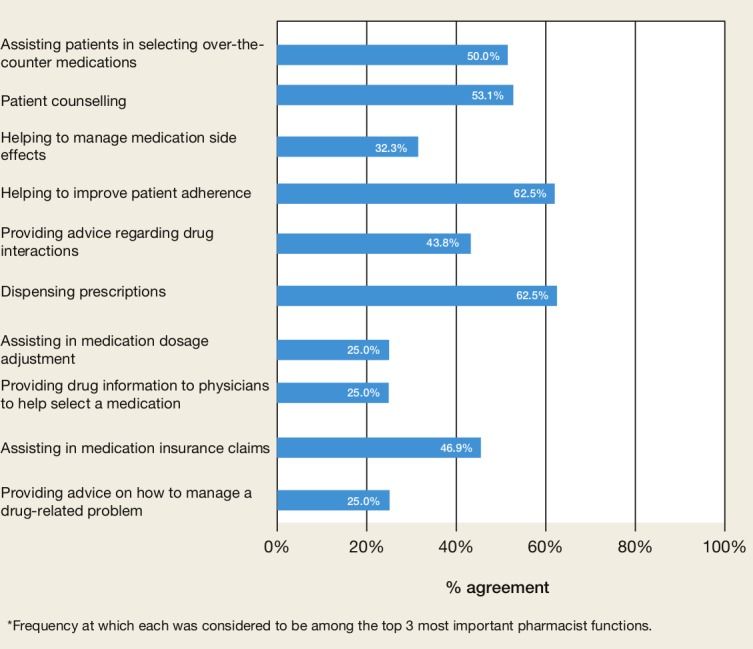

Pharmacists were asked to indicate the extent to which each of the tasks cited in Figure 4 were components of their role. There was a high level of agreement among pharmacists that all tasks were important, although assisting in medication insurance claims ranked the lowest.

Figure 4.

Pharmacist perceptions of the role of the community pharmacist

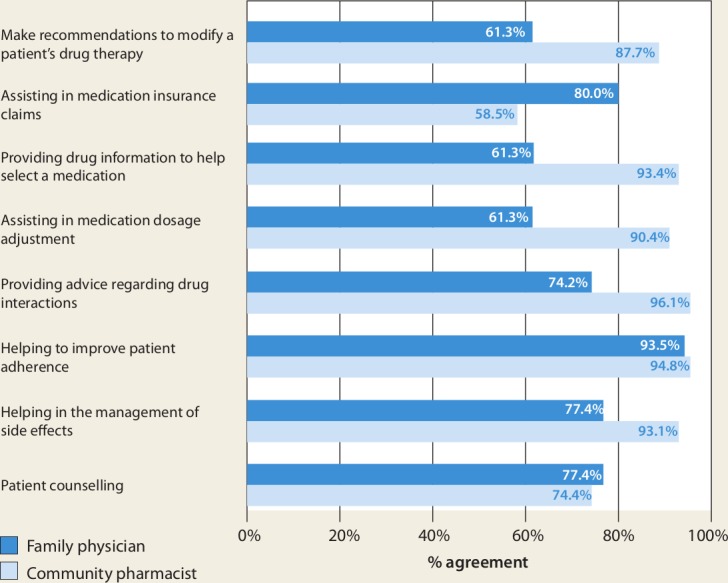

Physicians were asked to rank these same pharmacist functions in order of ability to improve patient care. Figure 5 describes the frequency with which each function was considered to be among the top 3 most important tasks of community pharmacists with respect to ability to improve patient care.

Figure 5.

Family physician perception of the importance of community pharmacist functions*

Physicians believed that the most important pharmacist functions were to help improve patient adherence and to fill prescriptions. They rated functions in which the pharmacist made recommendations to physicians regarding modification of a patient’s drug therapy as least important.

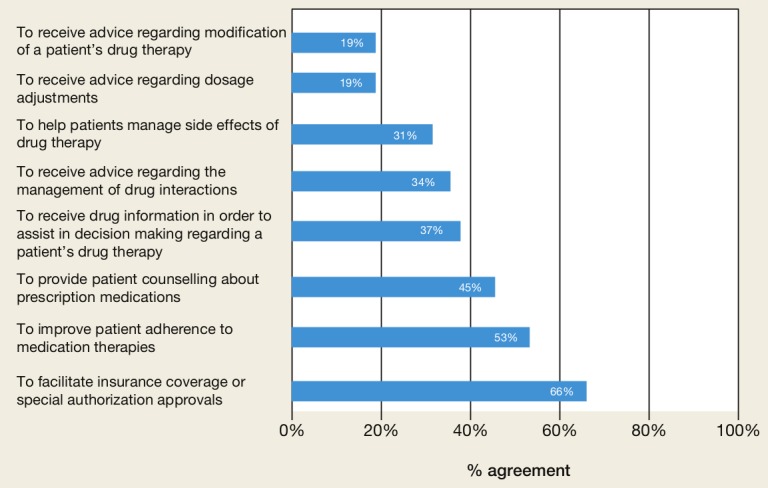

Physicians were also asked to indicate how frequently they use the community pharmacist for each of these tasks to provide patient care (Figure 6). Physicians reported collaborating with pharmacists most frequently to facilitate insurance approvals, to improve patient adherence and to provide counselling about prescription medications. Physicians reported collaborating least frequently to receive advice to adjust drug dosages or to add/discontinue/modify patient drug therapy to manage a specific drug-related problem.

Figure 6.

Areas in which physicians collaborate with pharmacists to provide patient care

Areas for further collaboration

Both groups were asked if they would like more collaboration to provide patient care. Pharmacists and physicians indicated they would like to collaborate more in all areas identified. However, there were slight differences in the level of agreement for some of these. In general, physicians indicated they would like to collaborate more in areas where they are already collaborating—to improve adherence, facilitate insurance approvals and for patient counselling. This is in contrast to pharmacists who responded they would like to participate more in decisions regarding identification and management of drug-related problems—managing drug interactions, providing drug information to inform decisions around patient drug therapy and assisting to modify drug therapy to resolve patient-specific problems. Pharmacists were less interested in collaborating to facilitate insurance approvals, an area that fewer pharmacists considered part of their professional role (Figure 4).

Although physicians indicated that receiving advice for side effect management was less important than other pharmacist functions and was an area where collaboration was not occurring often (Figures 5 and 6), this was an area where both physicians and pharmacists indicated they would like more collaboration (Figure 7). Both groups agreed they would like more collaboration on optimizing medication adherence.

Figure 7.

Areas for further collaboration between pharmacists and family physicians

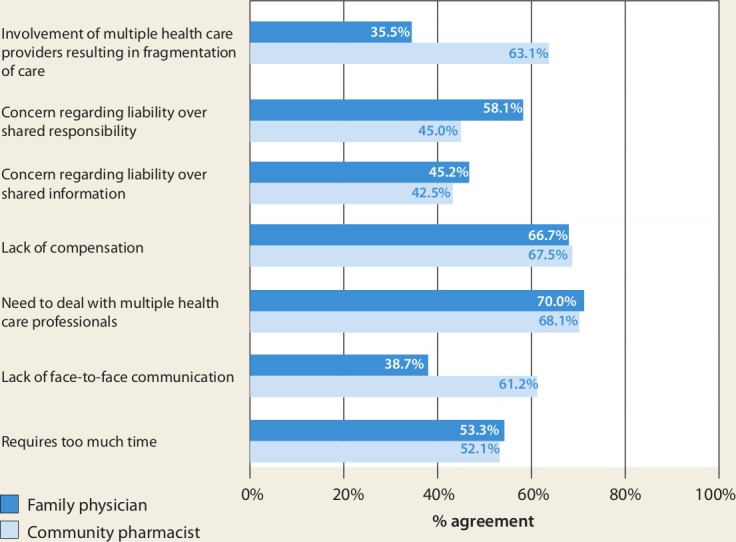

Barriers to collaborative practice

Pharmacists and physicians generally agreed regarding barriers to collaborative practice (Figure 8). Lack of compensation and the need to collaborate with multiple physicians/pharmacists to provide care for patients were viewed as the 2 most significant barriers. More than 50% of pharmacists and physicians agreed that time was also a prohibitive factor.

Figure 8.

Barriers to collaborative practice

Pharmacists expressed concern over the lack of face-to-face communication with physicians and the potential for multiple care provider involvement to result in more fragmented health care delivery. While not overly concerned about sharing patient information from a privacy perspective, physicians did express concern regarding risk-management issues relating to shared patient responsibility that would result from collaborative practice.

Discussion

Community pharmacists and the family physicians who participated in this study agree that collaborative practice can improve patient outcomes. Participants in this study indicated they had limited experience working collaboratively, which is consistent with findings from another Canadian study.17 However, both groups expressed desire to improve this relationship. There was interest in having more collaboration in all areas identified, although some areas were of greater interest to each group. Physicians wanted more support from pharmacists in areas related to the dispensing of medications—with insurance approvals, improving patient adherence and counselling. Pharmacists wished to collaborate in areas that more fully use their specialized knowledge and skills in assessing medication appropriateness, effectiveness and tolerability. Both groups indicated high agreement with wanting to collaborate more to improve medication adherence, which was identified as an important pharmacist role by both pharmacists and physicians. It has been suggested that the belief of physicians that collaboration will result in improved medication adherence may strongly influence their likelihood of collaborating with community pharmacists.18

There were differences identified in the perceived role of pharmacists. Physicians generally viewed the role to be more technical and tied to dispensing prescriptions, placing less value on more cognitive pharmacist functions. Similar studies have also indicated a disconnect between pharmacist and physician perceptions regarding the pharmacist’s role in patient care.3,6,19 One study found that physicians viewed selecting over-the-counter medication, detecting potential drug interactions and helping with adherence issues as potential pharmacist roles, whereas pharmacists themselves viewed advising physicians about best medication regimens as a major aspect of their role.6 A more recent study also found less physician support for pharmacists recommending the use of certain prescription medications to either patients or physicians or for assisting physicians in designing drug therapy treatment plans for their patients.18

However, attitudes can be changed with experience and observing the benefits of collaborative practice. Working in collaborative practice teams has been shown to help team members better understand each other’s roles and expertise.20,21 It has been suggested that changes directed at patients, care providers and practice environment can result in successful changes in practice.22 One study identified physician concerns related to operational efficiencies, medicolegal implications, effects on patient-physician relationships and work satisfaction prior to working with pharmacists.21 However, after working collaboratively with pharmacists for 12 months, several of these issues had resolved and the benefits of collaboration, including enhanced clinical support and collegiality, were realized. Ideally, both professions should have experience with collaborative practice during their undergraduate professional training and can continue to build on these experiences once in practice, for example, by attending joint continuing education activities and conferences. It has also been suggested that by educating physicians about their patient-focused services and taking advantage of opportunities to illustrate their drug therapy expertise, pharmacists can foster the development of collaborative practice relationships with physicians.17 Indeed, the public’s expectations for an expanded scope and breadth of services from community pharmacists23 support the need for health care professionals to collaborate more effectively.

Lack of time and remuneration were identified as prohibitive factors to collaboration in this study. This is consistent with opinions of Saskatchewan physicians, who believe that collaboration can improve patient outcomes, but find that time constraints and financial barriers limit the extent to which physicians and pharmacists interact to provide care.7 Until recently, in NL as well as most other provinces in Canada, pharmacist services reimbursed by public payers were primarily those associated with dispensing prescriptions. Pharmacists’ desire to apply their knowledge and skills to enhance patient care is hampered in an environment in which remuneration is tied to the dispensing of a product, rather than for services rendered. A recent analysis of remuneration models for pharmacy professional services indicates that the method of remuneration does appear to influence the provision of such services, noting that in countries where pharmacists are paid a flat fee to cover all services provided, there is a lack of incentive to provide more or higher-quality service.24 Physicians who have worked in collaborative practice with pharmacists have also indicated that the fee-for-service remuneration model is not conducive to sustaining these relationships.3,14 Blended payment models used by interdisciplinary Family Health Teams in Ontario allow physicians to collaborate with other health care professionals and provide more services to patients.25 Intuitively, financial models that reimburse the time required for collaboration or provide salary rather than fee-for-service may be more conducive to supporting collaborative practice, but further study is warranted to define an optimal remuneration model.

Many of the pharmacists from this study believed that electronic transfer of information should be explored as a method of communication. Although a provincial Drug Information System (DIS) was not available in NL when this study was conducted, several provinces across Canada have implemented province-wide DIS, which allows for enhanced communication among health care providers.26 The presence of a DIS will enable the sharing of patient information across the health care continuum and may offer additional opportunities for pharmacists and physicians to engage collaboratively.27

One drawback of this study is that it was conducted several years ago, prior to recent regulatory changes that have enabled expanded scope of pharmacist practice in most provinces in Canada. This may limit its generalizability, as attitudes and barriers to collaborative practice may have changed since this time. In addition, comparative statistics were not used to compare pharmacist and physician responses to similar questions, so only descriptive comparisons of the study results can be made. Another limitation was the low response rate to the physician survey. Other similar studies reported response rates ranging from 22% to 39%.7,17-19 Evidence suggests that physician response rates to surveys or questionnaires may be less than ideal, although the reasons for this are unclear.28,29 Several factors may have negatively affected our response rate, including the inability to survey the physicians via telephone and the lack of incentive offered for completed surveys. The relatively low physician response rate raises the possibility of nonresponder bias, and those with stronger opinions regarding collaborative practice may have been more likely to complete the survey. This limits the generalizability of the results to a broader physician population; however, the consistency of our results with other studies supports the validity of our findings, particularly with respect to the pharmacist data.

The very high pharmacist response rate was a strength of this study. This occurred for several reasons: a comprehensive and current telephone listing for all pharmacists at their place of work was used; trained, professional callers conducted the surveys; and the study investigators were well known to the pharmacy community.

Conclusion

Family physicians and community pharmacists agree that collaborative practice can positively affect patient care and would like to collaborate more in future; however, they differ in the areas in which they would like more collaboration. More traditional areas of collaboration involving insurance approvals and adherence or counselling interventions may have influenced these opinions. Greater collaborative practice experience may be needed to create appreciation and demand for more pharmacist involvement in modifying and monitoring patients’ drug therapy.

Pharmacists and physicians agree that the greatest barriers to collaborative practice include lack of compensation, insufficient time and the need to collaborate with multiple physicians/pharmacists. Changes to reimbursement models and infrastructure such as province-wide DIS and electronic health records may be needed to realize the full benefit of collaborative practice between pharmacists and physicians to support provision of optimal patient care. ■

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. S. Ann Colbourne, Mr. Jerry Young and Dr. Patrick O’Shea to the Community Pharmaceutical Care Project. As well, we express our sincere thanks to the pharmacists and physicians who participated in this project.

Footnotes

Financial acknowledgments:This study was funded by the Best Practices Program, Health Canada and the Office of VP (Research), Memorial University of Newfoundland.

References

- 1. Task Force on a Blueprint for Pharmacy Blueprint for pharmacy: the vision for pharmacy. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chisholm-Burns M, Lee JK, Spivey CA, et al. US pharmacists’ effect as team members on patient care. Med Care 2010;48:923-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chisholm-Burns M, Graff Zivin JS, Lee JK, et al. Economic effects of pharmacists on health outcomes in the United States: a systematic review. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2010:67:1624-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nkansah N, Mostovetsky O, Yu C, et al. Effect of outpatient pharmacists’ non-dispensing roles on patient outcomes and prescribing patterns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(7):CD000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sellors J, Kaczorowski J, Sellors C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a pharmacist consultation program for family physicians and their elderly patients. CMAJ 2003;169:17-22 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howard M, Trim K, Woodward C, et al. Collaboration between community pharmacists and family physicians: lessons learned from the Seniors Medication Assessment Research Trial. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2003;43:566-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laubscher T, Evans C, Blackburn D, et al. Collaboration between family physicians and community pharmacists to enhance adherence to chronic medications. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:e69-75 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lalonde L, Hudon E, Goudreau J, et al. Physician-pharmacist collaborative care in dyslipidemia management: the perception of clinicians and patients. Res Social Admin Pharm 2011;7:233-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hughes CM, McCann S. Perceived interprofessional barriers between community pharmacists and general practitioners: a qualitative assessment. Br J Gen Pract 2003;53:600-6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dobson RT, Henry CJ, Taylor JG, et al. Interprofessional health care teams: attitudes and environmental factors associated with participation by community pharmacists. J Interprof Care 2006;20:119-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Muijrers PE, Knottnerus JA, Sijbrandij J, et al. Changing relationships: attitudes and opinions of general practitioners and pharmacists regarding the role of the community pharmacist. Pharm World Sci 2003;25:235-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brock KA, Doucette WR. Collaborative working relationship between pharmacists and physicians: an exploratory study. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2004;44:358-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spencer JA, Edwards C. Pharmacy beyond the dispensary: general practitioners’ views. BMJ 1992;304:1670-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bell HM, McElnay JC, Hughes CM, Woods A. A qualitative investigation of attitudes and opinions of community pharmacists to pharmaceutical care. J Soc Adm Pharm 1998;15:284-95 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zillich AJ, McDonough RP, Carter BL, Doucette WR. Influential characteristics of physician/pharmacist collaborative relationships. Ann Pharmacother 2004;38:764-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nathan A, Sutters CA. A comparison of community pharmacists’ and general practitioners’ opinions on rational prescribing, formularies and other prescribing related issues. J Roy Sci Health 1993;113:302-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pojskic N, MacKeigan L, Boon H, et al. Ontario family physician readiness to collaborate with community pharmacists on drug therapy management: lessons for pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2009;142:184-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kucukarslan S, Lai S, Dong Y, et al. Physician beliefs and attitudes toward collaboration with community pharmacists. Res Soc Admin Pharm 2011;7:224-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alkhateeb FM, Unni E, Latif D, et al. Physician attitudes toward collaborative agreements with pharmacists and their expectations of community pharmacists’ responsibilities in West Virginia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2009;49:797-800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dieleman SL, Farris KB, Feeny D, et al. Primary health care teams: team members’ perceptions of the collaborative process. J Interprof Care 2004;18:75-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pottie K, Farrell B, Haydt S, et al. Integrating pharmacists into family practice teams: physicians’ perspectives on collaborative care. Can Fam Physician 2008;54:1714-1717e5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 2003;362:1225-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ipsos Reid poll With inter-provincial working group seeking transformative and innovative healthcare sustainability, majority of Canadians support private sector pharmacies extending products and services into avenues of healthcare. June 25, 2012. Available: www.ipsos-na.com/news-polls/pressrelease.aspx?id=5673 (accessed Aug. 2, 2012).

- 24. Bernsten C, Andersson K, Gariepy Y, Simoens S. A comparative analysis of remuneration models for pharmaceutical professional services. Health Policy 2010;95:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kantarevic J, Kralj B, Weinkauf D. Enhanced fee-for-service model and physician productivity: evidence from family health groups in Ontario. J Health Econ 2011;30:99-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Canada Health Infoway National impact of generation 2 drug information systems technical report, executive summary, September 2010. Available: https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/index.php?option=com_googlesearchcse&n=30&Itemid=1307&cx=004947342097296117226%3A3cbkgdvxvm8&cof=FORID%3A11&ie=ISO-8859-1&q=The+National+Impacts+of+Generation+2&hl=en (accessed July 31, 2012).

- 27. The Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information The Pharmacy Network. Available: www.nlchi.nl.ca/index.php/the-pharmacy-network (accessed July 31, 2012).

- 28. Grava-Gubins I, Scott S. Effects of various methodologic strategies: survey response rates among Canadian physicians and physicians-in-training. Can Fam Physician 2008;54:1424-30 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Creavina ST, Creavina A, Mallena C. Do GPs respond to postal questionnaire surveys? A comprehensive review of primary care literature. Fam Pract 2011;28:461-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]