Abstract

Family caregivers (FCGs) of lung cancer patients face multiple challenges which impact their quality of life and well-being. Whether challenged physically, emotionally, socially or spiritually, distress in one area may compound challenges in other areas. In order to maintain function and health of FCGs as they provide valuable care for the health and well-being of the patient, attention must be given to the needs of FCGs for support and education. The purpose of this article is to describe the multifaceted challenges that FCGs of lung cancer patients experience using case studies selected from a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded Program Project Grant “Palliative Care for Quality of Life and Symptom Concerns in Family Caregivers of Lung Cancer Patients.” The cases are discussed in terms of how the FCG’s quality of life is impacted by the caregiver role as well as how stressors in one or more domains of quality of life compound difficulties in coping with the demands of the role. The importance of the oncology nurse’s assessment of FCGs’ needs for support, education, and self-care through the lung cancer illness trajectory is discussed while presenting accessible community resources to meet those needs.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer and the number one cause of death in the United States with over 200,000 cases diagnosed each year accounting for 14% of all new cancer cases (American Cancer Society, 2011; Siegel, Naishadham, & Jemal, 2012). Recommended treatment can be complex with surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy alone or in combination. Symptom burden of the disease or treatment is profound, and impacts the patient as well as the family caregiver (FCG) who supports the patient.

FCGs face multiple challenges throughout the illness trajectory, evolving over time from the initial diagnosis of a life threatening illness, throughout treatment, to living with the potential for disease progression and end-of-life care. Each FCG brings his/her own life experience, coping abilities, and support systems to the role. How FCGs respond to the challenges of their roles impacts their ability to continue care for their family member through the illness trajectory. Anticipating, assessing and addressing the challenges of the FCG are integral to caring for and supporting the lung cancer patient. The oncology nurse must address the FCG’s needs throughout the illness trajectory to support the health and well-being of the lung cancer patient as well as his/her caregiver.

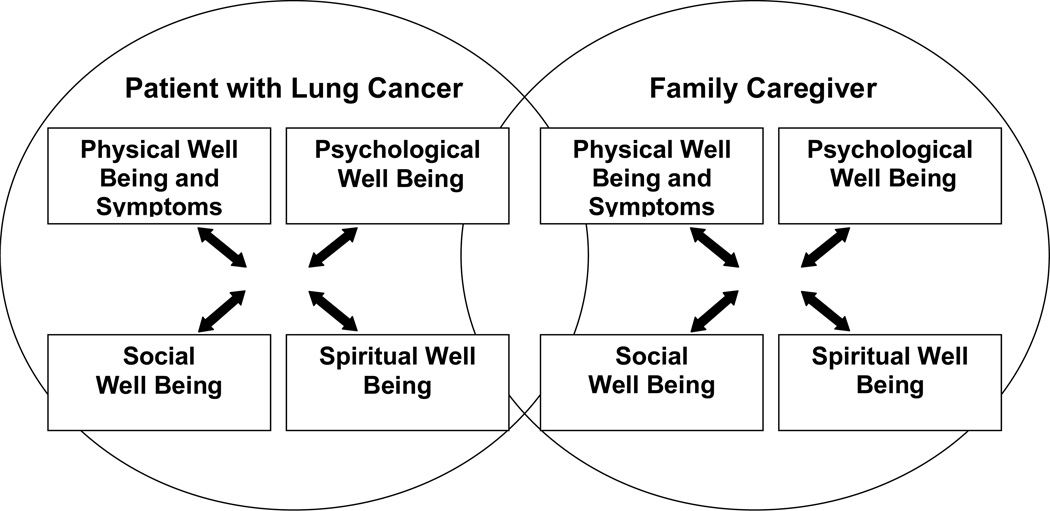

Examining lung cancer’s impact on FCG quality of life (QOL) is one way to better understand the experience and assess the challenges of the caregiver. QOL was defined by Grant and colleagues (Grant, Padilla, Ferrell, & Rhiner, 1990) as ‘a personal statement of the positivity or negativity of attributes that characterize one’s life.’ Each FCG brings his/her own physical, psychological, social and spiritual strengths and weaknesses to the role. The QOL of the FCG and the QOL of the patient with lung cancer affect each other throughout the illness trajectory (Northouse, 2005; Ryan, Howell, Jones, & Hardy, 2008; Siminoff, Wilson-Genderson, & Baker, 2010) (Figure 1). The demands of the FCG role as well as FCG’s bearing witness to the patient’s suffering impact FCG’s QOL and ability to function.

Figure 1.

Quality-of-Life Model Applied to Lung Cancer

Ferrell B, Primary investigator (2009) 5 P01 CA136396-02: Palliative Care for Quality of Life and Symptom Concerns in Lung Cancer. National Cancer Institute. City of Hope National Medical Center.

The purpose of the article is to 1) describe the current science regarding QOL of FCGs of lung cancer patients, 2) utilize two FCG cases to describe QOL issues that impact FCGs while caring for someone with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and 3) discuss assessment of FCGs and suggest interventions and resources to address the QOL deficits of FCGs of patients with NSCLC.

CAREGIVER QUALITY OF LIFE

Physical Well-being

The physical and emotional toll of caregiving in NSCLC with high potential for symptom burden may negatively impact the physical health of the FCG. FCGs are concerned about disease progression and treatment outcomes, while working with the practical demands of care (Bevans & Sternberg, 2012). In a study regarding sick leave usage of spouses of cancer patients, spouses of lung cancer patients had the most sick leave episodes, which may correlate with higher physical and emotional burdens of care (Sjovall et al., 2010). As disease progresses, physical care and assisting the patient with daily activities may be necessary. Added caregiver stress may result in sleep disturbance, fatigue, and unhealthy behaviors (Bevans & Sternberg, 2012). Sleep loss may result in changes in stress response, glucose regulation, and immune function (Bevans & Sternberg, 2012; Carter, 2003; Rivera, 2009; Wells-Di Gregorio et al., 2012).

Health behaviors and health changes of the FCG may be negatively impacted following cancer diagnosis (Beesley, Price, & Webb, 2011). This occurs when caregiving interferes with usual daily activities and is associated with negative lifestyle changes (Beesley et al., 2011). Caregivers appear to prioritize the care of the patient and lose focus on self care potentially resulting in decline of QOL (Bevans & Sternberg, 2012; Gibbins et al., 2009).

Psychological Well-being

Caring for a loved one with lung cancer is associated with both positive and negative psychological well-being (Ekwall & Hallberg, 2007). FCGs who are in strong relationships with ample support may find that their relationship grows stronger through the intimacy of caregiving, while those for whom the relationship is more complicated and who lack adequate support for the intensity of this role may experience significant caregiver burden (Chen et al., 2009). Increased caregiver burden increases the risk for depression and anxiety (Bevans & Sternberg, 2012).

FCGs often report a parallel roller-coaster of emotions mirroring the impact of the disease trajectory with the patient (Murray et al., 2010). Both FCG and patient experience the uncertainties and fears associated with a new diagnosis, decisions about treatment choices, symptoms and loss of function. The potential for stress associated with the role of caregiver places those with a history of psychological challenges at increased risk for deepening depression or heightened anxiety (Carter & Acton, 2006; Nijboer, Tempelaar, Triemstra, van den Bos, & Sanderman, 2001). Those who rely upon alcohol or other substances to manage stress are at risk for increased usage and may benefit from additional education and support (Sherwood et al., 2008).

Social Well-being

Adequate social support is critical to success in caregiving (Fineberg & Bauer, 2011). The responsibilities of the caregiving role vary and are influenced by gender, age, culture, and ethnicity (Northouse, 2005). The increased intimacy and vulnerability associated with caring for an increasingly debilitated loved one alters the roles of all involved. Strong relationships may find that bonds are tightened through the caregiving experience, while conflicted relationships or those with limited resources may be overwhelmed (Northfield & Nebauer, 2010; Northouse, 2005).

Worsening illness places increasing burdens upon FCGs who become fatigued and lack the time to continue normal social activities. This loss of a social network increases a sense of isolation and is associated with worse psychological well-being (Glajchen, 2011). FCGs find that the increasing demands of care may lead to missed time from work, decreased productivity, and job resignation (Mazanec, Daly, Douglas, & Lipson, 2011). Financial burden and social isolation are exacerbated by these changes.

Increased caregiving responsibilities can alter sexual expression and increase tension between partners (Gallo-Silver, 2011). Partners can be challenged to maintain a loving intimate relationship when required to assist with wound care or worried about causing pain or symptom distress. Communication is vital to maintain a positive intimate experience while coping with the side effects of treatment and progressive illness (Lindau, Surawska, Paice, & Baron, 2011).

Spiritual Well-being

Spiritual or existential well-being involves a sense of meaning and purpose in life (Lehto, 2012). A diagnosis of lung cancer invites both the patient and caregiver to attempt to find meaning in the illness experience (Kim, Carver, Spillers, Crammer, & Zhou, 2011; Northouse, 2005). Each must find a source of inner strength to face the inherent uncertainties associated with lung cancer (Murray et al., 2010).

For both patients and FCGs, hope evolves over time and each may find that they are hoping for different things. Initially, both patients and their loved ones may hope that the diagnosis was a mistake, or hope that the treatment will be successful. If end of life approaches, FCGs may vacillate between hope that their loved one is “miraculously cured” and hope that they will die “in peace.” FCGs may feel guilt about their own good health while a loved one is dying. Culturally sensitive spiritual and existential care is especially important in addressing the anticipatory grief of FCGs and in providing compassionate bereavement support to families following the death of the patient (Otis-Green, 2011).

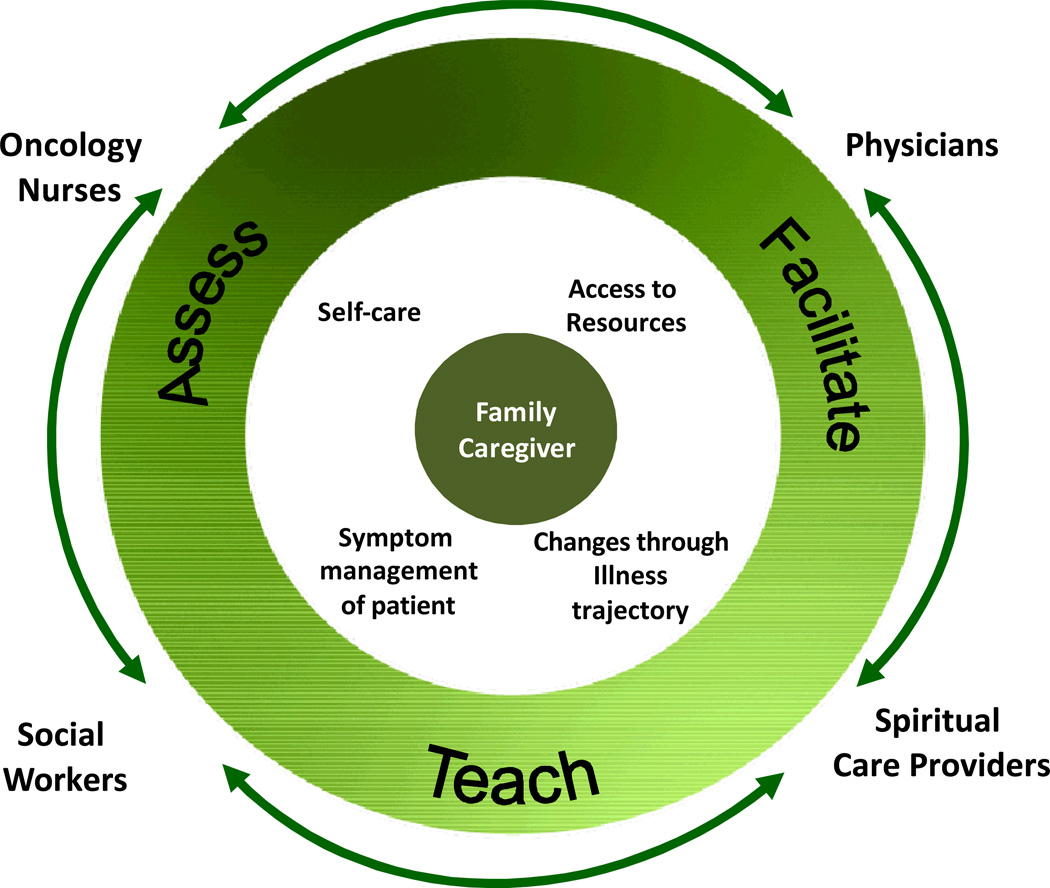

Integrated Palliative Care

Because of the multi-dimensional aspects of the caregiving experience, an interdisciplinary, team-based approach to providing bio-psychosocial-spiritual care is critical. Early integration of palliative care offers opportunities for delivery of services in anticipation of patient and family needs (Temel et al., 2010). Figure 2 illustrates the overlapping roles of the interdisciplinary team and highlights the importance of continuous collaborative communication in addressing the multi-dimensional needs of the FCG.

Figure 2.

Roles of Interdisciplinary Team in Care of the FCG.

Methods

Two composite caregiver case studies were selected from a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded Program Project Grant to provide perspective of the complex issues faced by FCGs while caring for the patient with NSCLC. The primary purpose of the Program Project is to test the efficacy of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention delivered by advance practice nurses for patients and families living with NSCLC. During Phase 1, FCGs (N=163) of patients receiving usual care for NSCLC were recruited over a one year period into an Institutional Review Board approved study from the Medical Oncology Adult Ambulatory Care Clinic at an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Specially trained research nurses accrued each FCG who then completed surveys and self-reports at baseline, 7, 12, 18, and 24 weeks following accrual. FCGs were asked about demographics and chronic illnesses. Using validated tools, FCGs were assessed for QOL, distress level, functional level, level of preparedness for caregiving, and caregiver burden. The case studies presented are composites of FCGs and were informed by both the questionnaires and from interviews. The criteria for selection of the cases presented was to include those with major challenges in two or more domains of QOL (physical, psychological, social, spiritual) to provide a perspective of issues faced by FCGs of NSCLC patients.

Caregiver Case Study 1

Mr. B. is a 62-year-old Caucasian male who is caring for his 72-year-old Filipino wife with stage IV NSCLC. Mrs. B. has completed several lines of chemotherapy with disease progression. Mr. B is in excellent health with no chronic health problems, and he works full time as a manager. They have two children and five grandchildren. Mrs. B. is especially close to one grandson who she spends time with on a regular basis. Mr. and Mrs. B and their grandson were recently able to travel to her family homestead in the Philippines.

Mr. B and his wife do not ‘see eye to eye’ on important issues and they have different styles of coping. They have accrued a large debt with home remodeling. Mrs. B would like to take another trip to the Philippines. Although Mr. B would like to accommodate her wishes, he feels they cannot afford more debt. He also cannot afford more time away from work as he needs to conserve time to care for her at home when her condition declines.

Mr. B was raised as a Protestant but does not subscribe to any religion as an adult. Mrs. B. is a Catholic and gains support from her faith and church community. Mr. B finds meaning and purpose in life from his family and providing for their needs. He also derives meaning from his work while experiencing the stress of multiple demands on his time.

Mr. B has great difficulty coping with his wife’s disease and treatment. He rates himself on a scale from 0 to 10 as having very little control in life (2/10), high levels of depression (7/10), and distress (7/10). He consistently accompanies his wife to her appointments with the medical oncologist. He states he has questions that he would like to ask the oncologist but feels it is his wife’s desire to be the one to ask questions and relay symptom information. Mr. B. expresses concern that his questions or discussion of Mrs. B.’s symptoms may cause her to lose hope. He also expresses that his needs and concerns when seeing the medical oncologist are not priorities.

Mr. B describes waves of emotion and an inability to control his feelings of helplessness, anger and fear. He chooses not to share his feelings with his wife fearing he may cause her more distress. While struggling with many unknowns, he is anticipating being alone in the home they have shared for over 40 years. He perceives that his responsibility as a caregiver is to protect Mrs. B. from suffering and negativity.

Discussion 1

This case study demonstrates multiple challenges in three domains of one FCG’s QOL. Table 1 “Assessment of the Family Caregiver” summarizes the oncology nurse’s approach to assessment of FCG needs.

Table 1.

Assessment of a Family Caregiver

KEY THINGS TO REMEMBER

|

CAREGIVER ASSESSMENT TOOLS AND LINKS

|

Adapted from reference (Levine, 2011)

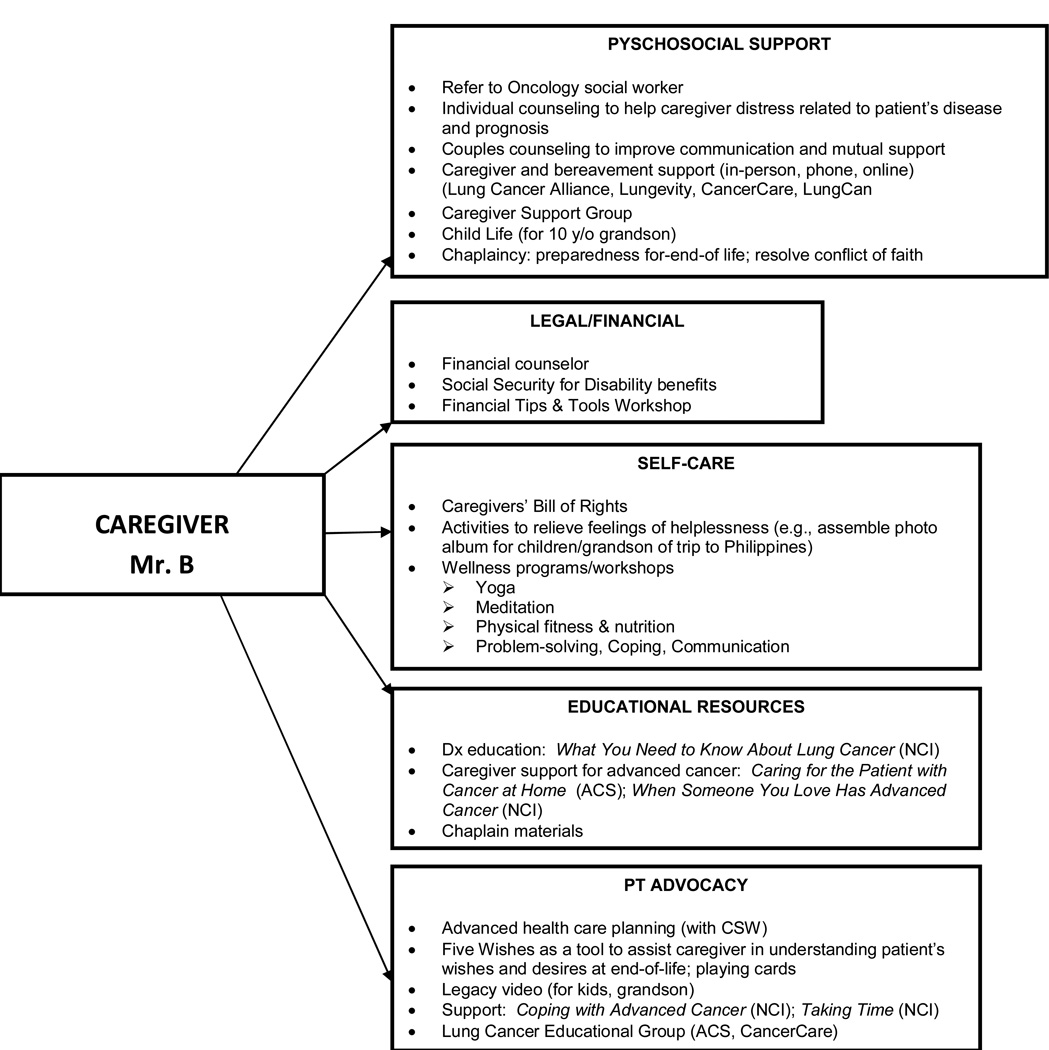

Needs may be prioritized according to which are most distressing or which may, once addressed, help alleviate distress in other areas. Mr. B’s communication with his wife may be considered a priority need. His decision to not share his concerns with his wife may negatively impact their relationship, creating emotional distance that contributes to a sense of isolation and loneliness for them both. One way to help bring them to ‘the same page’ may be by having them speak separately and as a couple with the oncology social worker about their feelings and stressors of dealing with lung cancer. Once they have shared their feelings, fears, and hopes for their future, they may be assisted to reconcile their goals and as a couple create a plan to meet those goals. This may have the additional benefit of relieving Mr. B’s psychological and spiritual distress. Referral to a caregiver support group may normalize Mr. B’s concerns as he benefits from the shared knowledge and experience of other caregivers. Figure 3 shows resources the oncology nurse may offer to Mr. B to meet his needs.

Figure 3.

Family Caregiver-Mr. B

Caregiver Case Study 2

Mrs. M. is a 53-year-old Hispanic caring for her 55-year-old Hispanic husband with advanced NSCLC. Mr. M. worked as a truck driver until his recent diagnosis and is now disabled. Mrs. M. has chronic illnesses including obesity, osteoporosis, arthritis, diabetes and depression. She was a hair dresser who has been disabled for 10 years. Mrs. M. has major problems with fatigue, pain, and insomnia. She rates herself on a scale of from 0 to 10 as having poor physical health (3/10). She is dealing with chronic lower back and right hip pain. At times the pain is so severe that she is in a wheelchair when she accompanies her husband to the medical oncology clinic.

Mrs. M. reveals that her mother died 1 1/2 years ago after a 2 year battle with breast cancer. Mrs. M was the caregiver for her mother. She rates her distress with her husband’s diagnosis as high (9/10). She fears that she will not be physically capable of caring for her husband as she did for her mother.

Mrs. M. rates her level of depression as high (8/10). Her treatment for depression has included seeing a psychiatrist and taking antidepressants. She stopped both about one year ago when she decided she could no longer drive on the freeway limiting her ability to continue in therapy. She also revealed that she and her husband have histories of alcohol abuse for which they were both rehabilitated.

Mrs. M. is Catholic and has a strong faith. Prayer and reading the Bible everyday help her to stay positive and feel supported. When she feels afraid, angry, isolated, or alone she reads biblical passages for support, and this helps her to work through her troubles.

Mrs. M. manages the couple’s finances. They are stressed financially since both are on disability. His job was terminated after 6 months on medical leave of absence. They are paying for his insurance out of pocket on COBRA using their disability income and some financial assistance from her sister.

Mrs. M. manages Mr. M.’s care. She comes to his appointments with him and maintains a detailed calendar with notes regarding his treatments, test results, and questions. During visits to the oncology clinic she gathers information about diet and the amount of activity that is best for her husband’s health during his treatment.

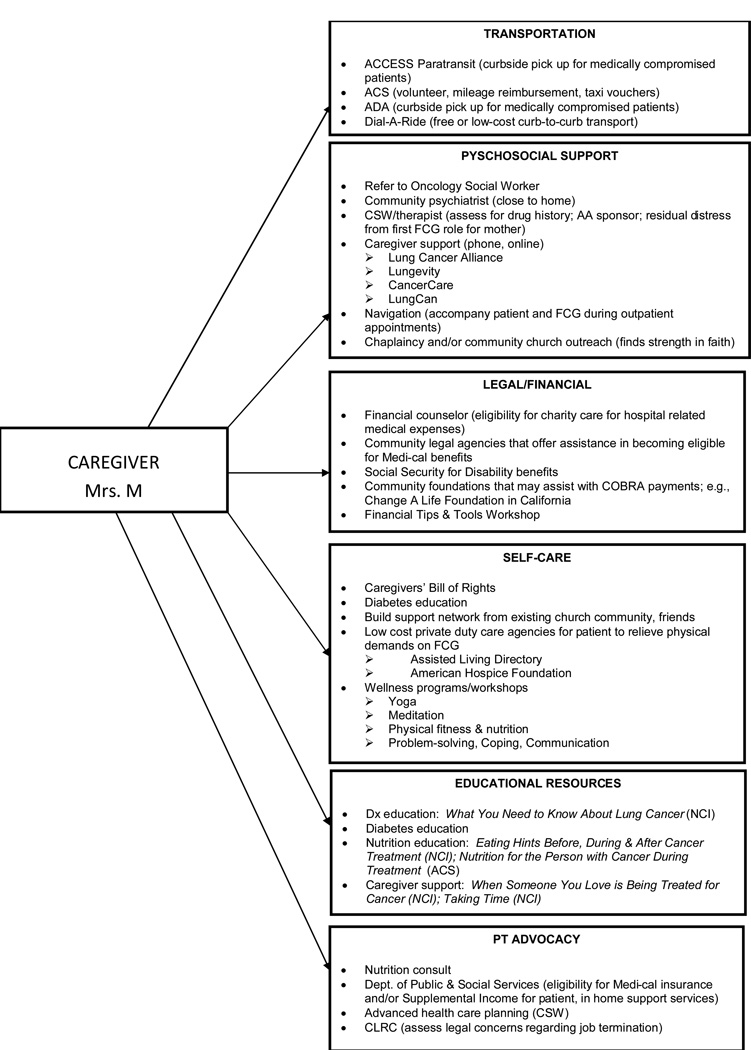

Discussion 2

In assessing Mrs. M’s goals as FCG, the oncology nurse would note that Mrs. M wishes to learn her husband’s treatment and to provide support for her husband’s health, while managing home and finances. Mrs. M recognizes that she needs a level of stamina and functional ability to meet the demands of the caregiver role. She has a significant amount of emotional distress regarding her physical health and her ability to continue her caregiving responsibilities. The oncology nurse may be instrumental in alleviating her worry and fear by identifying resources to assist with Mr. M’s care when it is beyond what Mrs. M is physically able to fulfill. Figure 4 presents resources the oncology nurse might offer Mrs. M.

Figure 4.

Resources for Family Caregiver-Mrs. M

Assessment by the clinical social worker or psychologist of Mrs. M’s history of alcoholism and depression may help in understanding her vulnerability to relapse. Early intervention to provide support and education may help her deal with distress, depression and uncertainty associated with her role. The importance of early intervention in areas of greatest vulnerability is apparent to support and maximize her QOL.

Identification of Mrs. M’s strengths provides an opportunity to discuss how she has coped in the past and may effectively cope in the present. Mrs. M’s prior experience as a caregiver for her mother is one area to explore with her to remind her of her strengths. She has indicated a strong connection to her faith and gains support and comfort in her spiritual activities. As Mrs. M deals with fears and frustrations, she may call upon her existing repertoire of strengths to cope.

Conclusion

The lung cancer experience from initial diagnosis through all phases of the disease can profoundly affect caregiver’s well-being and ability to function. Two case studies of FCGs of lung cancer patients demonstrate the complexity of challenges faced by the FCG and how challenges in one area can compound challenges in another. The oncology nurse has the opportunity to be available and to listen to the FCG, to anticipate and assess each FCG’s needs for support and education, and to convey that FCG well-being is a priority of care. After assessment and identification of priority needs, the oncology nurse may team with other disciplines to intervene with the best available resources (Table 2). The QOL of the patient with lung cancer and the QOL of the FCG affect each other. Palliation of symptom concerns for both must be addressed in comprehensive oncology care

Table 2.

Resources for Family Caregivers

| Resource | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Advance Health Care Planning | ||

| Caring Connections | www.caringinfo.org | State specific advance directive |

| Five Wishes | www.agingwithdignity.org | Living will that expresses personal needs: medical, personal, emotional, and spiritual |

| Bereavement | ||

| American Hospice Foundation | www.americanhospice.org | Care and support for grieving people of all ages; includes publications to purchase |

| Center for Loss & Life Transition | www.centerforloss.com/bookstore/ | Books for child, teen, and adult mourners written by Alan D. Wolfelt, PhD |

| Grief Recovery Online for All Bereaved | www.groww.org | Online grief support |

| Grief Net | www.griefnet.org | Online community, resources and support for people dealing with grief, death, and major loss |

| Growth House | www.growthhouse.org | Educational material about the end-of-life with books for caregivers and health care workers |

| Kids Konnected | www.kidskonnected.org | Education and support for children and teens who have a parent with cancer |

| Legacy Videos |

www.alovinglegacy.org www.zarpz.com |

Provides the seriously ill of all ages an opportunity to share their legacy on video |

| MD Junction | www.mdjunction.org | Bereavement support groups |

| Moyer Foundation’s National Bereavement Resource Guide | www.moyerfoundation.org/pdf/NationalBereavementResourceGuide_2010Update.pdf | Bereavement resources for children and adults |

| The Arnold C. Yoder Survivors Foundation | www.theacy.org | Grief support and education for children and adults |

| Education | ||

| American Cancer Society |

www.cancer.gov 1-800-227-2345 |

|

| CancerCare Fact Sheets |

www.cancercare.org; 1-800-813-HOPE (4673) |

|

| Cancer Support Community | www.Cancersupportcommunity.org | Information, resources and support community for all impacted by cancer |

| National Alliance for Caregiving | www.caregiving.org | Education, resources and advocacy for family caregivers |

| National Cancer Institute | www.cancer.gov |

|

| National Family Caregiving Association | www.nfcacares.org | Education, resources, and advocacy for FCG |

| UCSF Caregivers Project Orientation to Caregiving: A Handbook for Family Caregivers of Patients with Serious Illness | www.cancer.ucsf.edu | Handbook developed to provide easily accessible and accurate information to family caregivers caring for loved ones with serious illness. |

| Housing, Assisted Living, Home Health & Hospice Care | ||

| AARP Caregiving Help & Advice | https://caregiving.genworth.com | Nationwide home health care resources |

| Assisted Living Directory | www.assisted-living-directory.com | Senior care experts help locate the best assisted living facility for you and your loved one, nationwide |

| Cleaning For A Reason | www.cleaningforareason.org | Free professional house cleanings for women undergoing cancer treatment |

| Hospice Foundation of America | www.hospicefoundation.org | End-of-life care resources for patients, families and professionals |

| Joe’s House | www.joeshouse.org | Assists cancer patients and their families find lodging near treatment centers nationwide |

| New Life Styles | www.newlifestyles.com | National directory and resources for senior care, assisted living, home health, and hospice care |

| Individual and Family Counseling | ||

| Caregiver Health Insurance and Mental Health Benefits | Medical Insurance Card | Determine if caregiver carries medical insurance and is eligible for mental health services. Link caregiver to marriage and family therapist, licensed clinical social worker, psychologist and/or psychiatrist in their coverage plan. |

| LiveStrong | www.livestrong.org | Free, confidential counseling referrals for patients and caregivers. |

| National Alliance on Mental Illness | www.nami.org | Nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization |

| National Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration | www.samhsa.gov | Substance abuse and mental health services |

| Legal/ Financial Assistance | ||

| Brenda Mehling Cancer Fund | www.bmcf.net | Provides financial assistance for medical and legal services, housing, home healthcare, travel, phone bills, for cancer patients ages 18 to 40. |

| Cancer Legal Resource Center | www.disabilityrightslegalcenter.org | Free, confidential information on cancer-related legal issues |

| Chronic Disease Fund | www.cdfund.org | Financial assistance for expediting therapy |

| Employment Development Department (State of California) | www.edd.ca.gov | Apply for State Disability Insurance (SDI) and unemployment. |

| Family Medical Leave Act | www.dol.gov | Entitles eligible employees to take unpaid, job-protected leave |

| Feeding America | www.feedingamerica.org | Nation’s leading domestic hunger-relief charity |

| Financial Counselors | On-staff | Refer to the financial counselor at your facility |

| Give Forward | www.giveforward.org | Online tool that enables friends and family to send financial support to patients as they navigate a medical crisis |

| HealthWell Foundation | www.healthwellfoundation.org | Financial assistance for eligible individuals to cover coinsurance, copayments, healthcare premiums and deductibles for certain treatments |

| Lazarex Cancer Foundation | www.lazarex.org | Financial assistance to defray the costs associated with patient participation in FDA clinical trials |

| LeafLit | www.leaflit.com | Medical debt reduction and management |

| Merck Patient Assistance Program | www.merck.com | Prescription coverage for those who cannot afford medications |

| National Organization of Rare Disorders | www.raredisorders.org | Prescription coverage for those who cannot afford life-sustaining medications |

| Partners in Care Foundation | www.picf.org | Financial resources for underserved children and families who face a catastrophic life event |

| Partnership for Prescription Assistance | www.pparx.com | Prescription coverage for those who cannot afford medications |

| Patient Access Network Foundation | www.panfoundation.org | Financial assistance to under-insured patients for medications |

| Patient Advocate Foundation (PAF) | www.patientadvocate.org | Mediation and arbitration services to assist patients with medical debt, insurance access and employment issues |

| Patient Services Incorporated | www.patientservicesinc.org | Provides premium or co-pay insurance assistance |

| Pharmaceutical Reimbursement Assistance Program | www.needymeds.com | Pharmaceutical sponsored non-profit program providing cancer drugs at reduced costs to patients in need. |

| Veterans Assistance | www.va.gov | Health and well-being services for veterans |

| Self-Care | ||

| Caregiver Bill of Rights | http://www.co.delaware.ny.us/departments/ltc/docs/CG_Caregiver_Bill_of_Rights.pdf | Healthy reminder of caregivers’ rights |

| CaringBridge | www.caringbridge.org | Free, personal and private websites that connect people experiencing a health challenge with family and friends |

| Lotsa Helping Hands | www.lotsahelpinghands.com | Free community web site on which to privately organize family and friends who volunteer help, matching with needed tasks on individualized calendar |

| Skype | www.skype.com | Free phone and video phone calls around the world |

| Touch, Caring & Cancer – Simple Instruction for Family and Friends | www.partnersinhealing.net | Instructional DVD on how to give comfort through touch and massage to a loved one with cancer |

| Yoga Bear | www.yogabear.org | Dedicated to promoting wellness and healing in the cancer community through the practice of yoga |

| Sexual Health & Intimacy | ||

| Fertile Hope | www.fertilehope.org | Reproductive information to patients whose medical treatments present the risk of infertility |

| International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health | www.isswsh.org | Resources, including provider referrals, for women’s sexual health |

| Sexuality and Cancer – For the Woman/Man Who Has Had Cancer and Her/His Partner | www.cancer.org | Education and resources on sexuality and cancer for men and women |

| Smoking Cessation | ||

| National Cancer Institute Help Line | 1-877-44U-QUIT (1-877-448-7848) | Smoking cessation counselors from the National Cancer Institute are available to answer smoking-related questions (English or Spanish) |

| Smokefree.gov | www.smokefree.gov | Counseling, support, tools and resources to quit smoking |

| Support Groups | ||

| Cancer Hope Network | www.cancersupportnetwork.org | One-on-one support for cancer patients and families |

| CancerCare | www.cancercare.org | Online, telephone and in-person support groups for patients, caregivers and those who have lost a loved one. |

| Caregiver Support Groups | Local hospitals/facilities | Refer to caregiver support groups in the caregiver’s community (offered by hospitals, churches, hospices) |

| HopeWell Cancer Support | www.hopewellcancersupport.org | Online community incorporating blogs and forums for patients and caregivers. |

| Imerman Angels | www.imermanangels.org | Personalized connections that enable 1-on-1 support among cancer patients and caregivers |

| LungCAN-Lung Cancer Action Network | www.lungcan.org/ | Provides resources related to lung cancer including emotional and psychosocial support for caregivers and patients |

| Lungevity | www.lungevity.org | Provides community for those impacted by lung cancer |

| MetaCancer: A Community of Survivors & Caregivers | www.metacancer.org | Resources and online support for metastatic cancer survivors and their caregivers |

| Phone Buddy Program, Lung Cancer Alliance | www.lungcanceralliance.org | Peer-to-peer telephone support for lung cancer patients and caregivers |

| Transportation | ||

| American Cancer Society | www.cancer.org | Transportation assistance for patients and caregivers to and from medical appointments (limited) |

| Angel Flight Network | www.aircharitynetwork.org | Air transportation for medically compromised patients and their families ≤ 1000 miles |

| CancerCare | www.cancercare.org | Transportation assistance for patients and caregivers to and from medical appointments |

| Corporate Angel Network | www.corpangelnetwork.org | Air transportation for medically compromised patients and their families ≥ 1000 miles |

| For Providers | ||

| Cancer Patient Education Network | www.cancerpatienteducation.org | Network of healthcare professionals who share experiences and best practices in all aspects of cancer patient education. |

| Communication Tips - Cultural Sensitivities | www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC | Asking about cultural beliefs in palliative care |

| Pain & Palliative Resource Center | http://prc.coh.org/ | Publications regarding family caregiving |

Implications for Practice.

-

*

Family caregivers of lung cancer patients are an essential part of the healthcare team and have a significant impact on the health and well being of patients.

-

*

Family caregivers of lung cancer patients have multidimensional needs which impact their overall quality of life and must be recognized and addressed by oncology nurses to support optimal function in their role as caregivers.

-

*

To effectively address the needs of the family caregiver, collaborative practice and intervention within the oncology treatment center as well as the family caregiver’s community should be mobilized.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge and thank the family caregivers and patients for their willingness to share their personal stories and for their participation in the study. The project is supported by Grant Number 5 PO1 CA136396-02 from the National Cancer Institute (PI: Ferrell). The authors also wish to acknowledge the contributions of Virginia Sun, RN, PhD and Marcia Grant, RN, DNSc, FAAN.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Fujinami, Research Specialist, Nursing Research & Education, Department of Population Sciences, City of Hope, Duarte, CA.

Shirley Otis-Green, Senior Research Specialist, Nursing Research & Education, Department of Population Sciences, City of Hope, Duarte, CA.

Linda Klein, Manager of Operations, Sheri & Les Biller Patient and Family Resource Center, Department of Supportive Care Medicine, City of Hope, Duarte, CA.

Rupinder Sidhu, Clinical Social Work, Department of Supportive Care Medicine, City of Hope, Duarte, CA.

Betty Ferrell, Professor and Research Scientist, Nursing Research & Education, Department of Population Sciences, City of Hope, Duarte, CA.

References

- American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Facts and Figures 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beesley VL, Price MA, Webb PM. Loss of lifestyle: health behaviour and weight changes after becoming a caregiver of a family member diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(12):1949–1956. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. [Case Reports Clinical Conference] JAMA. 2012;307(4):398–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PA. Family caregivers' sleep loss and depression over time. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, PHS.] Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(4):253–259. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200308000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PA, Acton GJ. Personality and coping: predictors of depression and sleep problems among caregivers of individuals who have cancer. J Gerontol Nurs. 2006;32(2):45–53. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20060201-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Tsai MC, Liu CL, Yu WP, Liao CT, Chang JT. Support needs of patients with oral cancer and burden to their family caregivers. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(6):473–481. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b14e94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwall AK, Hallberg IR. The association between caregiving satisfaction, difficulties and coping among older family caregivers. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(5):832–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg IC, Bauer A. Families and family conferencing. In: Altilio T, Otis-Green S, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Social Work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo-Silver LL. Sexuality, sensuality, and intimacy in palliative care. In: Altilio T, Otis-Green S, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Social Work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbins J, McCoubrie R, Kendrick AH, Senior-Smith G, Davies AN, Hanks GW. Sleep-wake disturbances in patients with advanced cancer and their family carers. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(6):860–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glajchen M. Caregivers in palliative care: Roles and repsonsibilities. In: Altilio T, Otis-Green S, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Social Work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, Padilla GV, Ferrell BR, Rhiner M. Assessment of quality of life with a single instrument. [Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] Semin Oncol Nurs. 1990;6(4):260–270. doi: 10.1016/0749-2081(90)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Spillers RL, Crammer C, Zhou ES. Individual and dyadic relations between spiritual well-being and quality of life among cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Psychooncology. 2011;20(7):762–770. doi: 10.1002/pon.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto RH. The challenge of existential issues in acute care: nursing considerations for the patient with a new diagnosis of lung cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2012;16(1):E4–E11. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.E1-E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Surawska H, Paice J, Baron SR. Communication about sexuality and intimacy in couples affected by lung cancer and their clinical-care providers. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):179–185. doi: 10.1002/pon.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec SR, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Lipson AR. Work productivity and health of informal caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Res Nurs Health. 2011;34(6):483–495. doi: 10.1002/nur.20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Grant L, Highet G, Sheikh A. Archetypal trajectories of social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing and distress in family care givers of patients with lung cancer: secondary analysis of serial qualitative interviews. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] BMJ. 2010;340:c2581. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Triemstra M, van den Bos GA, Sanderman R. The role of social and psychologic resources in caregiving of cancer patients. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Cancer. 2001;91(5):1029–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northfield S, Nebauer M. The caregiving journey for family members of relatives with cancer: how do they cope? The Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14(5):567–577. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.567-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse L. Helping families of patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32(4):743–750. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.743-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis-Green S. Grief and Bereavement Care. In: Qualls SH, Kasl-Godley J, editors. The Wiley Series in Clinical Geropsychology: End-of-Life, Grief and Bereavement: What Clinicians need to know. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2011. pp. 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera HR. Depression symptoms in cancer caregivers. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2009;13(2):195–202. doi: 10.1188/09.CJON.195.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PJ, Howell V, Jones J, Hardy EJ. Lung cancer, caring for the caregivers. A qualitative study of providing pro-active social support targeted to the carers of patients with lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2008;22(3):233–238. doi: 10.1177/0269216307087145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood PR, Given BA, Donovan H, Baum A, Given CW, Bender CM, Schulz R. Guiding research in family care: a new approach to oncology caregiving. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review] Psychooncology. 2008;17(10):986–996. doi: 10.1002/pon.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Wilson-Genderson M, Baker S., Jr Depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients and their family caregivers and the influence of family environment. Psychooncology. 2010;19(12):1285–1293. doi: 10.1002/pon.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjovall K, Attner B, Lithman T, Noreen D, Gunnars B, Thome B, Englund M. Sick leave of spouses to cancer patients before and after diagnosis. Acta Oncologica. 2010;49(4):467–473. doi: 10.3109/02841861003652566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells-Di Gregorio S, Carpenter KM, Dorfman CS, Yang H, Simonelli LE, Carson WE. Impact of breast cancer recurrence and cancer-specific stress on spouse health and immune function. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2012;26:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]