Abstract

This study illustrates the application of a latent modeling approach to genotype–phenotype relationships and gene×environment interactions, using a novel, multidimensional model of adult female problem behavior, including maternal prenatal smoking. The gene of interest is the mono-amine oxidase A (MAOA) gene which has been well studied in relation to antisocial behavior. Participants were adult women (N=192) who were sampled from a prospective pregnancy cohort of non-Hispanic, white individuals recruited from a neighborhood health clinic. Structural equation modeling was used to model a female problem behavior phenotype, which included conduct problems, substance use, impulsive-sensation seeking, interpersonal aggression, and prenatal smoking. All of the female problem behavior dimensions clustered together strongly, with the exception of prenatal smoking. A main effect of MAOA genotype and a MAOA× physical maltreatment interaction were detected with the Conduct Problems factor. Our phenotypic model showed that prenatal smoking is not simply a marker of other maternal problem behaviors. The risk variant in the MAOA main effect and interaction analyses was the high activity MAOA genotype, which is discrepant from consensus findings in male samples. This result contributes to an emerging literature on sex-specific interaction effects for MAOA.

Keywords: Female problem behavior, Antisocial behavior, Prenatal smoking, Monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), Gene× environment interaction

Precise phenotypic characterization is essential for detecting reliable genotype–phenotype relationships, particularly in the area of neuropsychiatric disorders where the phenotypes are known to be complex and multidimensional (Houle et al. 2010; Hall and Smoller 2010). The traditional approach in neuropsychiatric genetics has been to use categorical diagnostic phenotypes. However, limitations in this approach, particularly reduced power resulting from unmeasured phenotypic heterogeneity and ambiguity about appropriate thresholds given a continuous liability distribution, have fostered interest in quantitative traits as phenotypes for genetic studies (Plomin et al. 2009; Bloss et al. 2010). This interest in quantitative traits intersects with a rich tradition of latent modeling approaches, or structural equation modeling (SEM), in behavioral research (Kline 2005; Loehlin 2004). Nevertheless, latent modeling approaches have yet to be widely integrated into genetic studies of neuropsychiatric phenotypes (for exceptions see Medland and Neale 2010; Middeldorp et al. 2010; Sakai et al. 2010).

The current study will illustrate the application of SEM phenotypic models to a candidate gene analysis. For the purposes of this study, we emphasize two important facets of SEM that are of relevance to genetic studies. First, SEM reduces the impact of measurement error on a phenotype through specification of a latent factor composed of the covariance among related measures. Reduction of phenotypic measurement error may increase power to detect genetic signals (Schulze and McMahon 2004). Secondly, SEM involves testing of a priori models, which allows phenotypic models to be theory-guided while also allowing for modifications based on model fit to empirical data. Once a satisfactory phenotypic model is obtained, mean differences in latent factors as a function of genotype can be tested as well as genotype×environment (G×E) interactions.

Consideration of multivariate phenotypes in genetic studies is an emerging area of research in neuropsychiatric disorders where the simultaneous testing of multiple phenotypes is desirable due to the phenotypic complexity of the disorders. The approaches to defining a multivariate phenotype can be broadly grouped into exploratory (e.g., Ferreira and Purcell 2009; Lange et al. 2003) and confirmatory approaches (e.g., Medland and Neale 2010). In this study, we focus on the latter approaches, including confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and SEM, which pre-specify a phenotypic model. A method for integrating SEM with genetic data has been detailed by Medland and Neale (2010) and applied by Middeldorp et al. (2010) using the program MX (Neale et al. 2002). The current analyses add to this emerging approach by illustrating the analytic technique with a user-friendly SEM modeling program, AMOS (Arbuckle 2007b), and applying the analysis to a novel multidimensional phenotype.

One aim of the current study is to apply latent phenotypic modeling techniques in the context of a candidate gene association study. We illustrate the approach using female problem behaviors as a phenotype. Female problem behavior is an example of a phenotype that has been under-studied due to a predominant focus on male samples and male-specific manifestations of problem behaviors (for exceptions see Fontaine et al. 2009; Keenan et al. 2010; Moffitt et al. 2001). Research in male samples has typically focused on antisocial, substance use, and aggressive behaviors as dimensions of a problem behavior syndrome (Jessor and Jessor 1977). These dimensions are also broadly relevant to females, but defining features may be different. For example, aggressive predispositions in females may more frequently manifest in verbally aggressive, rather than physically aggressive, social encounters and relationships (Serbin et al. 2004; Zoccolillo 1993). There is also evidence that problem behavior in adult women may manifest in a recurrent pattern of irritable, disrupted relationships (e.g., harsh parenting) (Serbin et al. 2004; Zoccolillo et al. 2004; Jaffee et al. 2006). Personality dimensions, such as impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and aggression-hostility, can also be conceptualized as part of an externalizing spectrum that is relevant to both genders (Krueger et al. 2002). Prenatal smoking and other health-risk behaviors during pregnancy have also been conceptualized as part of a maternal problem behavior syndrome (Wakschlag et al. 2003). Although such female problem behavior phenotypes have been theorized, they have rarely been modeled with rigorous statistical methods. A strength of the current study is the detailed, multi-measure phenotypic characterization of the sample of adult women.

This phenotypic modeling approach also provides a unique opportunity to address one relatively specific, but highly controversial issue in the field. This is the question of whether the widely reported association of prenatal smoking and offspring antisocial behavior reflects a causal teratologic pathway (Baler et al. 2008; Wakschlag et al. 2002, 2006) or is related to genetic transmission of problem behaviors (Thapar et al. 2009; D’Onofrio et al. 2010; 2008; Maughan et al. 2004; Gilman et al. 2008; Silberg et al. 2003). In this latter alternative, prenatal smoking and offspring antisocial behavior are conceptualized as expressions of underlying behavioral tendencies which manifest as smoking during pregnancy in the mother and behavior problems early in life in her child. The advantage of the current study for informing this debate is that the study sample of women was recruited into a prospective pregnancy cohort and over-sampled for prenatal smoking, which was carefully quantified. Our modeling approach allows us to directly test the strength of the relationship between prenatal smoking and other maternal problem behaviors.

Because a primary goal of this paper is to illustrate the application of latent phenotype models to candidate gene studies, we consider the relationship between the mono-amine oxidase A (MAOA) gene and female problem behaviors. The MAOA gene encodes the monoamine oxidase A enzyme which degrades monoamines, particularly norepinephrine and serotonin, making it a critical regulator of neurotransmission (Buckholtz and Meyer-Lindenberg 2008). The gene is located on the X chromosome and contains a common functional polymorphism, an untranslated variable number tandem repeat (uVNTR) (Sabol et al. 1998) that has been extensively studied in relation to aggression and related traits (Buckholtz and Meyer-Lindenberg 2008). Using our phenotypic model of maternal problem behaviors, including prenatal smoking, we will test for association with the uVNTR MAOA polymorphism. This analysis represents an integration of maternal genetic, behavioral, and exposure data that could hold promise for predicting later child outcomes (Baler et al. 2008).

Previous work has suggested a G×E interaction whereby MAOA genotype influences problem behaviors by altering susceptibility to adverse environmental experiences (Caspi et al. 2002; Kim-Cohen et al. 2006). Attempted replications of this interaction have been mixed, although a recent meta-analysis reported an overall effect (Kim-Cohen et al. 2006). Much of this G×E research has been conducted in male samples where individuals with the low activity polymorphisms and exposure to adverse environments have increased risk for antisocial behavior. Studies that have examined MAOA×environment interactions in female samples have reported conflicting results, with some studies reporting the high activity polymorphism (MAOA-H) as the risk allele in the interaction (Sjoberg et al. 2007; Aslund et al. 2011; Prom-Wormley et al. 2009), some studies reporting MAOA-L as the risk allele in the interaction (Ducci et al. 2008; Widom and Brzustowicz 2006), and some studies reporting no interaction (Huang et al. 2004; Frazzetto et al. 2007). Part of the explanation for these mixed results is potentially attributable to genetic, phenotypic, and environmental heterogeneity. This study addresses some of the phenotypic limitations by modeling female-specific problem behavior dimensions.

We have previously published a paper examining MAOA×prenatal smoking interactions in the adolescent offspring of the mothers in this sample (Wakschlag et al. 2010). This previous paper documented a sex-specific MAOA×pre-natal smoking interaction in predicting antisocial behavior. Specifically, girls with the MAO-H genotype, but boys with the MAOA-L genotype were more susceptible to prenatal smoking exposure. These results, along with the previously discussed literature regarding possible sex differences in patterns of MAOA×environment interactions, further highlight the need for additional research on the impact of MAOA genotype in female samples. While our previous paper considered the children of mothers examined in the current report, the current results are entirely new and focus on the maternal sample only.

The current study focuses on modeling a novel multidimensional problem behavior phenotype in the adult mothers of the sample and systematically testing its association with MAOA polymorphisms. Study analyses will explore the following issues: (1) the strength of the theorized relationship between female problem behaviors and prenatal smoking, (2) association of the uVNTR MAOA polymorphism with female problem behavior, (3) association of childhood physical maltreatment with female problem behavior, and (4) MAOA× physical maltreatment interactions predicting female problem behavior. The primary G×E tests will only focus on factors showing main effects in order to reduce the multiple testing burden and maximize the chances of identifying biologically-plausible interactions (Munafo et al. 2009).

Method

Participants

Participants were from a prospective pregnancy cohort of non-Hispanic, white women recruited from a neighborhood health clinic in East Boston. The women were oversampled for prenatal smoking as part of the Maternal Infant Smoking Study of East Boston (MISSEB) conducted between 1986 and 1992 (Hanrahan et al. 1992; Tager et al. 1995). Women were eligible for MISSEB if they attended the East Boston neighborhood health clinic, were less than 20-weeks pregnant, and were at least 19 years of age. This study reports on data from the East Boston Family Study (EBFS), a follow-up of the cohort when the participants’ children were adolescents. A prior report from this sample focused on offspring problem behavior phenotypes and MAOA genotype (Wakschlag et al. 2010). The present report is the first from this sample to characterize maternal phenotypes and their relation to MAOA.

Three hundred forty-eight white, non-Hispanic women from the MISSEB cohort were eligible for the EBFS follow-up study. Of those eligible, data was obtained from 233 biological mothers for EBFS (67 %). A previous report has documented general comparability of the full MISSEB cohort and the EBFS subsample (Wakschlag et al. 2010). Of the 233 eligible women from EBFS, genotypic data was collected for 192 individuals. Thus, the final sample consisted of 192 (82 %) non-Hispanic, white women with behavioral data and genotypes. Descriptives for this sample are provided in Table 1. The 192 included women did not significantly differ from EBFS eligible non-participants on relevant demographics.

Table 1.

Demographics comparing included and ineligible EBFS mothers

| Included mothers (N=192)

|

Excluded mothers (N=41)

|

p valuea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 192 | 42.9 | 5.7 | 41 | 41.9 | 5.2 | 0.3240 |

|

|

|

||||||

| N | Frequency | Percent | N | Frequency | Percent | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| % prenatal smokers | 191 | 102 | 53.4 % | 41 | 16 | 39.0 % | 0.0947 |

| High school grad or GED | 192 | 171 | 89.1 % | 41 | 37 | 90.2 % | 0.8244 |

|

|

|

||||||

| N | Median | N | Median | ||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Years of education | 191 | 12 | 41 | 12 | 0.9132 | ||

| Income | 184 | $40,001–50,000 | 40 | $30,001–40,000 | 0.1261 | ||

Differences in continuous traits between included and excluded mothers were tested using a two-sample t-test. Differences in categorical traits were tested with a Chi-square test. Differences in non-normal or ordinal traits (i.e., years of education and income) were tested using a Mann–Whitney U test

Measures

Antisocial behavior

Mothers reported on their own antisocial behavior using the Antisocial Behavior Checklist (Zucker et al. 1994), a 45-item measure which assesses a range of delinquent behaviors divided into child and adult subscales. For the child subscale items, mothers reported retrospectively on their childhood behavior. Sample items included: “Skipped school without a legitimate excuse for more than 5 days in one school year” and “Broke street lights, car windows, or car antennas just for the fun of it.” For the adult subscale, mother reported whether they engaged in the behavior in the past year. Sample items included: “Snatched a woman’s purse” and “Taken part in a robbery.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83 for the child subscale and 0.79 for the adult subscale.

Substance use

Mothers completed the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) (Zung 1982) and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) (Skinner 1982). The MAST is designed to identify alcoholism using 25 yes/no questions that identify problematic behaviors associated with alcohol use. Sample items included: “Have you always felt that you were a normal drinker?” and “Have you ever been in a hospital because of your drinking?” Cronbach’s alpha for the MAST items was 0.89.

The DAST (Skinner 1982) assesses psychoactive drug misuse using 25 yes/no questions that target problem behaviors associated with drug use. Sample items included: “Have you ever abused prescription drugs?” and “Were you always able to stop using drugs when you want to? Cronbach’s alpha for the DAST items was 0.92.

Temperament/personality

Mohers completed the Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ) (Zuckerman 2002). The impulsivity (eight items), sensation seeking (11 items), and aggression-hostility (17 items) sub-scales were administered. Sample items included: “Before I begin a complicated job, I make careful plans,” “I like to do things just for the thrill of it,” and “When I get mad, I say ugly things. Cronbach’s alpha for the impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and aggression–hostility scales were 0.77, 0.78, and 0.76, respectively.

Aggressive relationships

Mothers completed questionnaires about aggression in their romantic and parenting relationships. Regarding romantic relationships, if the mother reported being in a relationship for 1 month or longer in the past year, she completed the Couples Conflicts and Problem-Solving Strategies Questionnaire (Kerig 1996), which assesses various dimensions of partner conflict. The verbal aggression (ten items) and moderate physical aggression (five items) dimensions of the violence subscale were the utilized in the current analyses. Sample items from the verbal aggression and moderate physical aggression scales included: “Raise voice, yell, shout,” “Interrupt, don’t listen to partner,” and “Throw something at partner.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84 for the verbal aggression scale and 0.63 for the moderate physical aggression scale.

Mothers also completed a questionnaire on parenting behavior derived from the Child Rearing Issues: Discipline subsection of the Hetherington Discipline Scale (Hetherington et al. 1992). This study focused on the punitive discipline subscale (17 items). Sample items included: “Ridiculed or put this child down when the two of you argued” and “Punished this child more severely than usual for misbehavior.” Cronbach’s alpha for the punitive discipline subscale, which we refer to as “harsh parenting” in the analyses, was 0.79.

Prenatal smoking

As part of the MISSEB study, women reported current smoking (average cigarettes per day) at each prenatal visit. Blood and urine were also obtained for cotinine assays, which were conducted by radioimmunoassay (Wang et al. 1997). Datapoints across the pregnancy were averaged. We used all three indicators of prenatal smoking to derive a latent factor (Dukic et al. 2007).

Childhood physical maltreatment

Mothers retrospectively reported on their history of childhood maltreatment and neglect on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ: Bernstein et al. 1994). Because many previous MAOA× environment interaction studies focused on severe maltreatment, this study selected only the physical maltreatment items (N=9) from the physical and emotional maltreatment subscale. Sample items included, “When I was growing up, people in my family hit me so hard that it left me with bruises or marks,” and “When I was growing up, people in my family pushed or shoved me.” Cronbach’s alpha for these physical maltreatment items was 0.94.

Genotyping

MAOA 5′ uVNTR genotyping

Saliva samples were collected from mothers using DNA Genotek Oragene Self-Collection Kits. After extraction, DNA was quantitated with a fluorescent Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay (Invitrogen, Carls-bad, CA, USA) and normalized to a concentration of 10 ng μl−1. DNA was amplified with PET forward primer 5′-PET-ACAGCCTGACCGTGGAGAAG-3′ (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and reverse primer 5′-(GTTTCTT)GAACGGACGCTCCATTCGGA-3′ (with pigtail sequence within parentheses) using HotStarTaq DNA Polymerase (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) with an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 58.2 °C and 2 min at 72 °C. Products were separated on a 3730 Genetic Analyzer (AppliedBiosystems) in the UIC Research Resources Center DNA Services Facility. Alleles were called blind to phenotype data using Genemapper v 3.7.

Quality control checks for genotyping included Mendelian error checks between mothers and offspring and tests of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of the four possible alleles (3, 3.5, 4, and 5) (p=0.318). There is agreement across studies that three repeats should be classified as Lower Activity (MAOA-L) and 3.5 and 4 repeats as High Activity (MAOA-H), but there is some discrepancy with regard to classification of five repeats (Sabol et al. 1998; Deckert et al. 1999). Consistent with the approach of Sabol and Kim-Cohen (Sabol et al. 1998; Kim-Cohen et al. 2006), we classified the five repeats as MAOA-L. Because MAOA is X-linked and so females have two copies of MAOA compared to males with one copy, studies have taken varying approaches to classifying heterozygous females. On the basis of earlier findings that patterns for heterozygous females are similar to those for females homozygous for the low-activity allele (Sjoberg et al. 2007), the current study classified female participants homozygous for four repeats or heterozygous with both high-activity genotypes (3.5 and 4 repeats) as MAO-H, and female participants with all other genotypes as MAO-L. Table 2 shows the frequency of MAOA genotypes in the sample. We confirmed these MAOA activity designations using a three-level classification of the most well-characterized and common genotypes, 3/3, 3/4, and 4/4 (93 % of the sample). Using a composite score derived from the Conduct Problems factor in the models below, we conducted an ANOVA using the three-level classification. Consistent with results reported below, there was a main effect of MAOA genotype on the Conduct Problems composite, F(2,175)=5.309, p<0.01, but post hoc tests showed that this effect was driven by the 4/4 genotype which was significantly higher in Conduct Problems than the 3/3 and 3/4 genotypes which did not differ from each other. These results supported our classification of the 3/3 and 3/4 genotypes into the MAO-L group in the main analyses.

Table 2.

Distribution of MAOA genotypes

| MAOA genotype | % (Count) | MAOA activity designation |

|---|---|---|

| 3/3 | 10 (20) | Lower |

| 3/3.5 | 1 (1) | Lower |

| 3/4 | 42 (80) | Lower |

| 3/5 | 2 (3) | Lower |

| 3.5/4 | 2 (4) | High |

| 3.5/5 | 1 (1) | Lower |

| 4/4 | 41 (79) | High |

| 4/5 | 2 (4) | Lower |

Data cleaning and analyses

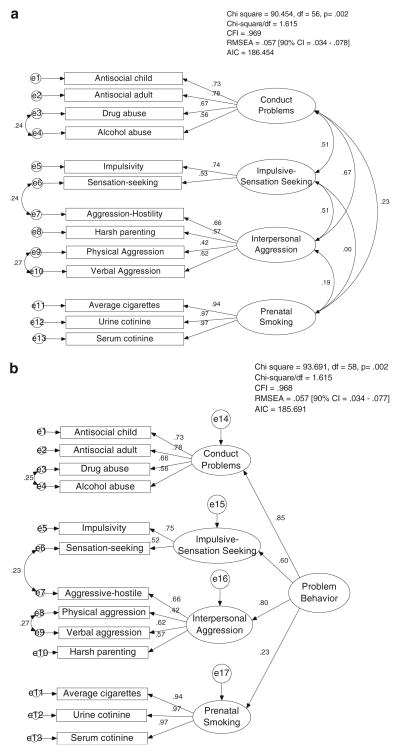

Composite scores from the questionnaires were used in the analyses. A missing item criterion was set such that questionnaires with more than 20 % of items skipped were considered missing datapoints (three for DAST, three for MAST, one for ZKPQ, two for Hetherington Discipline Scale). Sample outliers falling four standard deviations beyond the mean for the entire sample were winsorized to 4 SD. The following variables were log transformed: antisocial child, antisocial adult, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, harsh parenting, physical aggression, average cigarettes, urine cotinine, serum cotinine, and physical maltreatment because of violations of normality (skewness>1). Missing questionnaire and prenatal smoking information was minimal (1–15 %) with the exception of the Couples Conflicts and Problem-Solving Strategies Questionnaire (31 %), which required the mother to be in a relationship within the past year. SEM analyses were run with AMOS 16.0 using maximum likelihood estimation and imputation of missing data using full information maximum likelihood estimation (Arbuckle 2007b). To ensure that results were not due to imputation biases, we conducted a supplementary analysis including only individuals with complete data for all variables in the models except the variables with the most amount of missing data, the Verbal and Physical Aggression scales of the Couples Conflicts and Problem-Solving Strategies Questionnaire (remaining N=137). The second-order factor model depicted in Fig. 1b, which is the core model of the analyses, did not differ substantially in terms of model fit indices or factor loadings regardless of whether missing data was imputed (N=192) or only complete data was used (N=137).

Fig. 1.

a First-order CFA model. b Second-order factor model. Standardized factor loadings (β) and correlation coefficients are depicted by single-headed and double-headed arrows, respectively

Results

Model specification

The overall goal of these model-building analyses was to test the hypothesis that a single Problem Behavior factor (capital letters denote the factor name) most parsimoniously accounts for variation on several behavioral sub-dimensions, including antisocial behavior, substance use, temperament/ personality, aggressive relationships, and prenatal smoking. Table 3 shows the correlations between all the variables included in the model. Model specification began with a first-order confirmatory factory analysis (CFA) and proceeded to a second-order CFA. We used the following general guidelines for satisfactory model fit: χ2/df<3, Comparative Fit Index (CFI)>0.90, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)<0.08 (Kline 2005). Nested models were compared with a Chi-square difference tests and non-nested models with the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC). Residual errors of subscales from the same measure were permitted to correlate to allow for questionnaire-specific covariance. Residual covariances that did not improve model fit were trimmed.

Table 3.

Correlations among self-report measures of maternal problem behaviors

| Antisocial child | Antisocial adult | Drug abuse | Alcohol abuse | Impulsivity | Sensation seeking | Aggression–hostility | Physical aggression | Verbal aggression | Harsh parenting | Average cigarettes pregnancy |

Urine cotinine pregnancy | Serum cotinine pregnancy |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisocial childa | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Antisocial adult | 0.557*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Drug abuse | 0.477*** | 0.544*** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.367*** | 0.471*** | 0.521*** | 1 | |||||||||

| Impulsivity | 0.246** | 0.306*** | 0.182* | 0.239** | 1 | ||||||||

| Sensation seeking | 0.312*** | 0.188* | 0.228** | 0.109 | 0.396*** | 1 | |||||||

| Aggression–hostility | 0.484*** | 0.282*** | 0.287*** | 0.196** | 0.273*** | 0.310*** | 1 | ||||||

| Physical aggression | 0.194* | 0.220* | 0.213* | 0.198* | 0.261** | − 0.040 | 0.244** | 1 | |||||

| Verbal aggression | 0.325*** | 0.323*** | 0.296** | 0.212* | 0.175* | 0.121 | 0.383*** | 0.454*** | 1 | ||||

| Harsh parenting | 0.295*** | 0.309*** | 0.109 | 0.121 | 0.270*** | 0.071 | 0.347*** | 0.241** | 0.459*** | 1 | |||

| Average cigarettes | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.237** | 0.230** | 0.018 | − 0.024 | 0.173* | 0.111 | 0.065 | − 0.024 | 1 | ||

| Urine cotinine | 0.177* | 0.105 | 0.213** | 0.257*** | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.214** | 0.132 | 0.052 | 0.024 | 0.907*** | 1 | |

| Serum cotinine | 0.160* | 0.118 | 0.269** | 0.307*** | 0.008 | − 0.022 | 0.169* | 0.161 | 0.074 | − 0.040 | 0.906*** | 0.933*** | 1 |

Retrospective report of antisocial behavior problems in childhood

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

The final first-order CFA is depicted in Fig. 1a and showed satisfactory model fit. Two modifications were made to our original model to arrive at this final model. First, the Antisocial Behavior and Substance Abuse factors were collapsed into a single Conduct Problems factor because of the high correlation between these factors (r=0.87). Secondly, the Aggressive-Hostility personality dimension was more closely associated with Aggressive Relationships than the temperament/personality measures where it was initially placed. As a result, this variable was moved to the Aggressive Relationships factor and the resulting temperament/personality factor was renamed “Impulsive-Sensation Seeking,” a construct which is consistent with previous literature (Zuckerman 1994).

The second-order factor structure is depicted in Fig. 1b. Model fit was comparable to the revised first-order factor analysis as measured by similar AIC values and similar fit indices. The Problem Behavior higher-order factor showed strong and significant relationships (βs=0.60–0.85, ps< 0.001) with all of the first-order factors, with the exception of Prenatal Smoking which had a substantially weaker, albeit significant, relationship with the higher-order factor, β = 0.23, p<0.05. A critical ratio test showed that the Prenatal Smoking loading (β = 0.23) was significantly weaker than even the lowest loading factor, Impulsive-Sensation Seeking (β= 0.60), z = 3.615, p<0.001. This weak standardized path loading would typically indicate that the construct should be dropped from the factor because there is not enough coherence with other constructs. Nevertheless, this path was retained in the interest of further model testing with genotype information.

Main effects of MAOA

Following the establishment of measurement invariance between the MAOA genotype groups (data not shown), a multi-group CFA analysis (Byrne 2004) was used to test whether there was a mean difference in the Problem Behavior factor as a function of MAOA genotype. We chose this multi-group mean test over the alternative of including MAOA genotype as a predictor in the model. The former approach was preferred because the multi-group test of mean differences is more flexible in permitting tests of group differences in path weights, such as tests of G×E interaction which will be explored later.

The mean test of the second-order Problem Behavior factor is akin to an omnibus test that if significant can be further analyzed for mean differences in the subcomponents, or first-order factors. We tested for a mean difference in the second-order Problem Behavior factor by estimating the mean of the MAOA-H group while constraining the mean to 0 in the MAO-L group, an approach that is recommended in multi-group tests using AMOS (Sörbom 1974; Arbuckle 2007a). In this analysis, the following parameters were constrained to be equal across genotype groups based on the previous measurement invariance testing: first-order factor loadings, measurement intercepts, second-order factor loadings, and second-order factor variance. Results showed that the mean in the MAO-H group was significantly greater than 0, M=0.095, SE=0.038, z=2.522, p=0.012. (Note that the scaling of these factors is arbitrary and not interpretable beyond the relationship between the mean and standard error).

To further investigate the contribution of the underlying first-order factors to this mean difference, we used the same procedure to test for mean differences using the comparable first-order factor model (i.e., Fig. 1a). The mean of the four latent factors was estimated in the MAOA-H group but constrained to 0 in the MAOA-L group. The following parameters were constrained to be equal across genotype groups: first-order factor loadings, measurement intercepts, factor variances, and factor covariances. Results showed that the second-order Problem Behavior factor mean difference was primarily attributable to the Conduct Problems factor score, which was significantly greater than 0 in the MAOA-H group, M=0.109, SE=0.039, z=2.775, p=0.006. There were no significant mean differences between the MAO-H and MAO-L groups in Impulsive-Sensation Seeking (M= 0.359, SE=0.301, z=1.192, not significant (ns)), Interpersonal Aggression (M=0.676, SE=0.665, z=1.017, ns), or Prenatal Smoking (M=0.110, SE=0.075, z=1.456, ns). Overall, genotype analyses indicated that there are mean differences in Problem Behaviors associated with MAOA genotype that are primarily driven by differences in Conduct Problems (high MAOA activity associated with increased Conduct Problems).

Main effects of childhood physical maltreatment

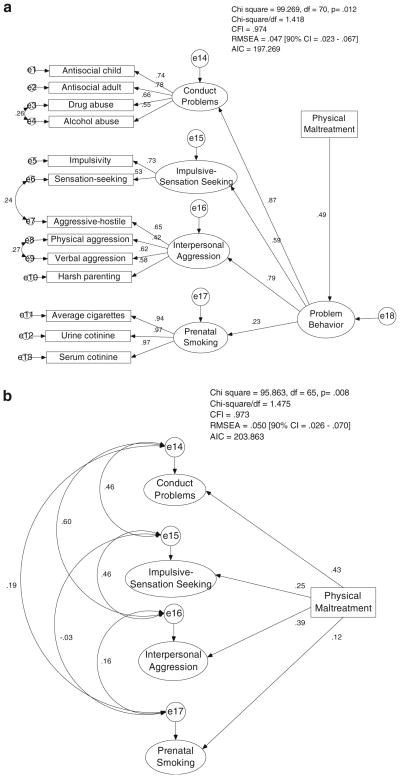

Maternal retrospective report of childhood physical maltreatment was tested for its association with the second-order Problem Behavior factor. Childhood physical maltreatment significantly predicted maternal Problem Behavior, β=0.49, p<0.001 (see Fig. 2a). We also examined the strength of prediction of childhood physical maltreatment to each of the first-order latent factors. Physical maltreatment significantly predicted each of the latent factors except Prenatal Smoking: β for Conduct Problems=0.43, p<0.001, β for Impulsive-Sensation Seeking=0.25, p<0.01, β for Interpersonal Aggression=0.39, p<0.001, β for Prenatal Smoking=0.12, ns (see Fig. 2b). Thus, these results indicated that physical maltreatment was a more generalized risk factor compared to MAOA genotype, which impacted primarily Conduct Problems. We also tested for differences in childhood physical maltreatment as a function of MAOA genotype using a t test, but found no significant evidence for a gene–environment correlation in this sample, t(181)=1.29, p=0.20.

Fig. 2.

a Main effect of childhood physical maltreatment on maternal problem behavior. b Main effect of childhood physical maltreatment on first-order latent factors underlying maternal problem behavior. The measurement components of the model are not shown in order to simplify the figure, but they are the same as depicted in Fig. 1a

Gene×environment interactions

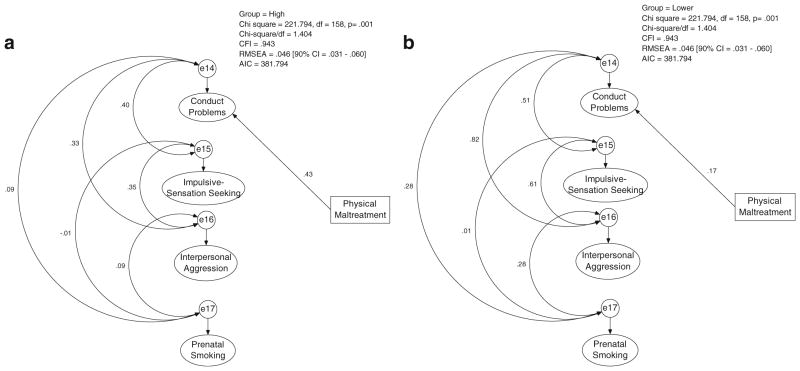

Given the evidence for MAOA and childhood physical maltreatment main effects on maternal Problem Behavior, we also tested for a possible G×E interaction. A multi-group model was used to test whether the path from physical maltreatment to the maternal Problem Behavior factor was significantly moderated by MAOA genotype group. The prediction of Problem Behaviors by physical maltreatment was estimated in both groups and statistically compared using a z statistic. The following parameters were constrained to be equal across genotype groups: first-order factor loadings, measurement intercepts, and second-order factor loadings. The path from childhood physical maltreatment to Problem Behavior was not significantly different in the genotype groups, z=1.323, ns. However, because the genetic main effect was primarily on the Conduct Problems factor, we also tested for a G×E interaction with this specific latent factor. In this analysis, the following parameters were constrained to be equal across genotype groups: first-order factor loadings and measurement intercepts. In this case, there was a significant G×E interaction where the path from childhood physical maltreatment to Conduct Problems was stronger in the MAO-H group (β=0.43, p<0.001) than in the MAO-L group (β=0.17, p<0.05), z=2.095, p<0.05. Figure 3 depicts this interaction. As an exploratory follow-up analysis, we also tested for G×E interactions with the remaining latent factors. No significant interactions were detected, all zs<1, ns.

Fig. 3.

MAOA×childhood physical maltreatment interaction predicting Conduct Problems. a High activity MAOA genotype group. b Lower activity MAOA genotype group

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to build a latent model of an under-studied phenotype, female problem behavior, and to illustrate the application of this model in quantitative genetic analyses. There are several novel aspects of the study. Perhaps most importantly, in the phenotypic modeling of female problem behavior, we included a diverse array of problem behavior clusters, including prenatal smoking and other proposed female-specific dimensions. Such problem behaviors with particular relevance to adult women are often neglected. We used this multivariate phenotypic model in genetic analyses which allowed us to reduce measurement error through latent modeling and test for genetic effects within our a priori phenotypic framework. The use of latent models in molecular and psychiatric genetics is still quite rare.

Results showed that a coherent Problem Behavior cluster could be constructed in this female sample, with strong contributions from Conduct Problems, Impulsive-Sensation Seeking, and Interpersonal Aggression. Importantly, our theorized female manifestations of problem behaviors, such as harsh parenting and verbal aggression in relationships, clustered well with more traditional measures of problem behavior, such as antisocial behavior. This was an important finding demonstrating that female problem behaviors impact both parenting and romantic relationships. This model is consistent with other multidimensional conceptions of problem behaviors (Krueger et al. 2002; Krueger et al. 2007). Our phenotypic model highlights the utility of measuring female-specific manifestations of problem behaviors, rather than focusing exclusively on male-specific dimensions, such as criminality and physical aggression (Moffitt et al. 2001; Fontaine et al. 2009; Keenan et al. 2010).

Another innovation pertained to our explicit testing of the relationship between female problem behaviors and prenatal smoking through the use of latent constructs. There remains substantial debate in the field regarding whether the maternal smoking-offspring behavior problem association reflects a teratogenic effect or is related to genetic transmission of problem behaviors. Two compelling lines of evidence support both sides of the debate. Quasi-experimental designs which can control for genetic relatedness have supported the genetic transmission hypothesis (Thapar et al. 2009; D’Onofrio et al. 2008, 2010; Maughan et al. 2004; Gilman et al. 2008; Silberg et al. 2003), whereas research in animal models clearly demonstrates a deleterious impact of smoking exposure on brain development supporting the teratogenic hypothesis (for reviews see Baler et al. 2008; Wakschlag et al. 2002). Building on foundational work by Krueger to model the multidimensional nature of problem behavior (Krueger et al. 2002, 2007), the present study used CFA to test the strength of the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and problem behavior clusters. Maternal Prenatal Smoking showed a significant relationship with Problem Behaviors consistent with previous research (Wakschlag et al. 2003), but the strength of this relationship was substantially weaker than for other dimensions of Problem Behavior in the mother. In fact, the Problem Behaviors factor only accounted for 5 % of the variance in Prenatal Smoking compared to 36 % of Impulsive-Sensation Seeking, 65 % of Interpersonal Aggression, and 72 % of Conduct Problems. Thus, a small amount of variance in prenatal smoking is shared with other problem behaviors in this unique sample, specifically selected for very high rates of prenatal smoking. These preliminary findings suggest that prenatal smoking is more than a simple marker of other maternal problem behaviors.

Once we had constructed the latent phenotypic model of female Problem Behavior, we used the model to test for genotype–phenotype relationships and gene×environment interactions using MAOA genotype. A replicable main effect of MAOA on problem behaviors has been difficult to document in both the male and female literature. In many cases, the main effect of the risk allele has been nonsignificant despite the interaction effect, as was the case in the first report by Caspi et al. (2002). One important difference between this study and previous studies is that the current study employed latent factors which reduce measurement error, an approach that may have afforded us increased power to detect a main effect of MAOA on maternal Problem Behaviors.

We also detected a nominally significant MAOA×environment interaction where the effect of physical maltreatment on Conduct Problems was stronger for mothers possessing the high activity MAOA genotypes than the lower activity MAOA genotypes. This is in contrast to a number of studies documenting the lower activity MAOA genotype as the risk allele in the interaction for male samples (e.g. Caspi et al. 2002; Kim-Cohen et al. 2006). We have previously reported a similar interaction pattern in daughters of the mothers in this sample (while controlling for mother antisocial behavior) (Wakschlag et al. 2010). Our result is consistent with several previous studies reporting an MAOA×environment interaction in females in the same direction as our findings (Sjoberg et al. 2007; Prom-Wormley et al. 2009), including a large, population-based study of adolescent females (Aslund et al. 2011). Nevertheless, there are also previous studies that have found MAOA× environment interactions in female samples that are incompatible with these results (Ducci et al. 2008; Widom and Brzustowicz 2006) and studies reporting no interaction (Huang et al. 2004; Frazzetto et al. 2007). Hence, we consider these results to be an addition to the existing literature that is still somewhat mixed regarding replication of MAOA×environment interactions in females, and regarding replication of gene×environment interactions in psychiatry more generally (Caspi et al. 2010; Risch et al. 2009; Munafo et al. 2009; Kim-Cohen et al. 2006; Karg et al. 2011; Duncan and Keller 2011). The mixed state of the literature makes replication of these findings using similar latent factor phenotypes an essential next step.

If the three-way interaction implied by the literature, gender×MAOA×environment, achieves consensus replication in large samples, it would suggest gender differences in the nature of this G×E interaction that could be important in the neurobiological pathways contributing to problem behaviors. Additional evidence for the same sex difference in the MAOA×environment interaction pattern is also suggested in the alcoholism literature (e.g., Nilsson et al. 2011). MAOA is an X-linked gene, and there is some evidence that it is one of the 15 % of X-linked genes that does not undergo X inactivation (Carrel and Willard 2005), although this evidence is not without qualification (e.g., Benjamin et al. 2000; Hendriks et al. 1992; Nordquist and Oreland 2006; Xue et al. 2002). Since the X-inactivation status of MAOA remains unresolved, the possibility of dosage differences between males and females remains an open question. Moreover, the enzyme MAOA is directly regulated by estrogen (Chakravorty and Halbreich 1997) and testosterone may influence MAOA transcription (Ou et al. 2006). Overall, complex relationships may exist between the dosage of this gene in males and females, hormonal influences, and brain systems underlying problem behaviors.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. This sample is small for a candidate gene study, which is why our primary genotype–phenotype tests were focused on specific hypotheses using a refined phenotype model: a single test of the main effect of MAOA on Problem Behaviors (with follow-up justified by the significant omnibus result) and two tests of G×E interaction with the factors demonstrating a main effect of MAOA. The history of candidate gene studies in psychiatric genetics where gene findings were documented in small samples but often not replicated in larger studies (Duncan and Keller 2011; Sullivan 2007) leads us to approach the nominal associations of problem behaviors with MAOA and the MAOA×physical maltreatment interaction with caution until consensus replication is obtained. Still, these results contribute to the emerging literature on MAOA×environment interactions predicting problem behaviors in females. We attempted to control for population stratification effects by limiting the sample to European–Americans. Future studies of MAOA may benefit from including a panel of ancestry informative markers to rule out the impact of subtle population stratification effects.

That the sample was over-sampled based on prenatal smoking status is both a strength and limitation for our purposes here. Since a central question for the field is whether maternal smoking is merely a marker for maternal problem behavior, high rates of maternal smoking are critical to addressing this issue. Oversampling provided us with a large proportion of smokers (~50 %) for analyses. Nevertheless, replication in a population-based sample will be necessary to establish external validity. In terms of phenotypic measurement, it is important to note that all measures were self-reported by the mother. Phenotypic characterization could be further strengthened by including ratings by other informants (e.g., parents, children, and partners) and methods (e.g. event-based reporting), ideally in a longitudinal design. The longitudinal design may be particularly important for further exploring the relation between problem behaviors and prenatal smoking as our measures of problem behaviors were obtained many years after the birth of the child. Thus, the weak relation between prenatal smoking and problem behaviors may be partially attributable to the time lag between the measurements. There is evidence that many of these problem behaviors are quite stable across the lifespan (e.g., Loeber 1991; Wakschlag et al. 2003; Fergusson et al. 2005), particularly personality measures (Roberts et al. 2001; e.g., Costa and McCrae 1997), but the issue still requires further investigation.

In conclusion, the results of this study inform phenotypic characterization of female problem behaviors, including the ongoing debate regarding the relationship between female problem behaviors and prenatal smoking. The quantitative genetic analyses contribute to the emerging MAOA×environment interaction literature where there are hints of sex-specific interaction effects for MAOA. More broadly, this study illustrates the application of latent models to genetic association tests. This SEM approach to genotype–phenotype relationships draws on the strengths of several disciplines by integrating the emphasis from the behavioral sciences on multivariate phenotype models and measurement precision with current methods in psychiatric and statistical genetics. This approach is applicable to a vast array of complex neuropsychiatric disorders where there are multidimensional quantitative traits believed to underlie the disorder. Integrating latent models into psychiatric and statistical genetic models could advance understanding of genotype–phenotype relationships and gene×environment interactions in complex neuropsychiatric disorders.

Contributor Information

L. M. McGrath, Email: mcgrath@pngu.mgh.harvard.edu, Psychiatric and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit, Department of Psychiatry and Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Simches Research Building 6th floor, 185 Cambridge Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

B. Mustanski, Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

A. Metzger, Department of Psychology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA

D. S. Pine, Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

E. Kistner-Griffin, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

E. Cook, Department of Psychiatry, Institute for Juvenile Research, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

L. S. Wakschlag, Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

References

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 16.0 User’s Guide. SPSS; Chicago: 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (version 16.0) SPSS; Chicago: 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Aslund C, Nordquist N, Comasco E, Leppert J, Oreland L, Nilsson KW. Maltreatment, MAOA, and delinquency: sex differences in gene-environment interaction in a large population-based cohort of adolescents. Behav Genet. 2011;41(2):262–272. doi: 10.1007/s10519-010-9356-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler RD, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Benveniste H. Is fetal brain monoamine oxidase inhibition the missing link between maternal smoking and conduct disorders? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33 (3):187–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin D, Van Bakel I, Craig IW. A novel expression based approach for assessing the inactivation status of human X-linked genes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8(2):103–108. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss CS, Schiabor KM, Schork NJ. Human behavioral informatics in genetic studies of neuropsychiatric disease: multivariate profile-based analysis. Brain Res Bull. 2010;83(3–4):177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholtz JW, Meyer-Lindenberg A. MAOA and the neurogenetic architecture of human aggression. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31 (3):120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: a road less traveled structural equation modeling. A Multidiscip J. 2004;11(2):272–300. [Google Scholar]

- Carrel L, Willard HF. X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature. 2005;434 (7031):400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature03479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, Taylor A, Poulton R. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297(5582):851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(5):509–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty SG, Halbreich U. The influence of estrogen on monoamine oxidase activity. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33 (2):229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Longitudinal stability of adult personality. In: Hogan R, Johnson JA, Briggs SR, editors. Handbook of personality psychology. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. pp. 269–290. [Google Scholar]

- Deckert J, Catalano M, Syagailo YV, Bosi M, Okladnova O, Di Bella D, Nothen MM, Maffei P, Franke P, Fritze J, Maier W, Propping P, Beckmann H, Bellodi L, Lesch KP. Excess of high activity monoamine oxidase A gene promoter alleles in female patients with panic disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(4):621–624. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Van Hulle CA, Waldman ID, Rodgers JL, Harden KP, Rathouz PJ, Lahey BB. Smoking during pregnancy and offspring externalizing problems: an exploration of genetic and environmental confounds. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20(1):139–164. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Singh AL, Iliadou A, Lambe M, Hultman CM, Grann M, Neiderhiser JM, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring criminality: a population-based study in Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):529–538. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducci F, Enoch MA, Hodgkinson C, Xu K, Catena M, Robin RW, Goldman D. Interaction between a functional MAOA locus and childhood sexual abuse predicts alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder in adult women. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(3):334–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukic VM, Niessner M, Benowitz N, Hans S, Wakschlag L. Modeling the relationship of cotinine and self-reported measures of maternal smoking during pregnancy: a deterministic approach. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(4):453–465. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LE, Keller MC. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1041–1049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2005;46(8):837–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MA, Purcell SM. A multivariate test of association. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(1):132–133. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine N, Carbonneau R, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Tremblay RE. Research review: a critical review of studies on the developmental trajectories of antisocial behavior in females. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):363–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazzetto G, Di Lorenzo G, Carola V, Proietti L, Sokolowska E, Siracusano A, Gross C, Troisi A. Early trauma and increased risk for physical aggression during adulthood: the moderating role of MAOA genotype. PLoS One. 2007;2(5):e486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Gardener H, Buka SL. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and children’s cognitive and physical development: a causal risk factor? Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(5):522–531. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MH, Smoller JW. A new role for endophenotypes in the GWAS era: functional characterization of risk variants. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):67–74. doi: 10.3109/10673220903523532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan JP, Tager IB, Segal MR, Tosteson TD, Castile RG, Van Vunakis H, Weiss ST, Speizer FE. The effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on early infant lung function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145(5):1129–1135. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks RW, Chen ZY, Hinds H, Schuurman RK, Craig IW. An X chromosome inactivation assay based on differential methylation of a CpG island coupled to a VNTR polymorphism at the 5’ end of the monoamine oxidase A gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1 (3):187–194. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG, Anderson ER, Deal JE, Hagan MS, Hollier EA, Lindner MS. Coping with marital transitions: a family systems perspective. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1992;57(2/3) [Google Scholar]

- Houle D, Govindaraju DR, Omholt S. Phenomics: the next challenge. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(12):855–866. doi: 10.1038/nrg2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Cate SP, Battistuzzi C, Oquendo MA, Brent D, Mann JJ. An association between a functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase a gene promoter, impulsive traits and early abuse experiences. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(8):1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Belsky J, Harrington H, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. When parents have a history of conduct disorder: how is the caregiving environment affected? J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(2):309–319. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: a longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Wroblewski K, Hipwell A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Age of onset, symptom threshold, and expansion of the nosology of conduct disorder for girls. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119 (4):689–698. doi: 10.1037/a0019346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: the conflicts and problem-solving scales. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10(4):454–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Taylor A, Williams B, Newcombe R, Craig IW, Moffitt TE. MAOA, maltreatment, and gene-environment interaction predicting children’s mental health: new evidence and a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(10):903–913. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(3):411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Benning SD, Kramer MD. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: an integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(4):645–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange C, Silverman EK, Xu X, Weiss ST, Laird NM. A multivariate family-based association test using generalized estimating equations: FBAT-GEE. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):195–206. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R. Antisocial behavior: more enduring than changeable? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(3):393–397. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent variable models. 4. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Prenatal smoking and early childhood conduct problems: testing genetic and environmental explanations of the association. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):836–843. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medland SE, Neale MC. An integrated phenomic approach to multivariate allelic association. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18(2):233–239. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp CM, Landt MC, Slof-Op ‘t, Medland SE, van Beijsterveldt CE, Bartels M, Willemsen G, Hottenga JJ, de Geus EJ, Suchiman E, Dolan CV, Neale MC, Slagboom PE, Boomsma DI. Anxiety and depression in children and adults: influence of serotonergic and neurotrophic genes? Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9(7):808–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex differences in antisocial behavior. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Durrant C, Lewis G, Flint J. Gene×environment interactions at the serotonin transporter locus. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65 (3):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: statistical modeling. 6. Departmentt of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University; Richmond: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson KW, Comasco E, Aslund C, Nordquist N, Leppert J, Oreland L. MAOA genotype, family relations and sexual abuse in relation to adolescent alcohol consumption. Addict Biol. 2011;16 (2):347–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordquist N, Oreland L. Monoallelic expression of MAOA in skin fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348(2):763–767. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou XM, Chen K, Shih JC. Glucocorticoid and androgen activation of monoamine oxidase A is regulated differently by R1 and Sp1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(30):21512–21525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Haworth CM, Davis OS. Common disorders are quantitative traits. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(12):872–878. doi: 10.1038/nrg2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prom-Wormley EC, Eaves LJ, Foley DL, Gardner CO, Archer KJ, Wormley BK, Maes HH, Riley BP, Silberg JL. Monoamine oxidase A and childhood adversity as risk factors for conduct disorder in females. Psychol Med. 2009;39(4):579–590. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, Liang KY, Eaves L, Hoh J, Griem A, Kovacs M, Ott J, Merikangas KR. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(23):2462–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. The kids are alright: growth and stability in personality development from adolescence to adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(4):670–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabol SZ, Hu S, Hamer D. A functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene promoter. Hum Genet. 1998;103(3):273–279. doi: 10.1007/s004390050816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai JT, Boardman JD, Gelhorn HL, Smolen A, Corley RP, Huizinga D, Menard S, Hewitt JK, Stallings MC. Using trajectory analyses to refine phenotype for genetic association: conduct problems and the serotonin transporter (5HTTLPR) Psychiatr Genet. 2010;20(5):199–206. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32833a20f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze TG, McMahon FJ. Defining the phenotype in human genetic studies: forward genetics and reverse phenotyping. Hum Hered. 2004;58(3–4):131–138. doi: 10.1159/000083539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, Stack DM, De Jenna M, Grunzeweig N, Temcheff CE, Schwartzman AE, Ledingham J. When aggressive girls become mothers. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior and violence among girls. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. pp. 262–285. [Google Scholar]

- Silberg JL, Parr T, Neale MC, Rutter M, Angold A, Eaves LJ. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk to boys’ conduct disturbance: an examination of the causal hypothesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(2):130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg RL, Nilsson KW, Wargelius HL, Leppert J, Lindstrom L, Oreland L. Adolescent girls and criminal activity: role of MAOA-LPR genotype and psychosocial factors. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B(2):159–164. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7 (4):363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörbom D. A general method for studying differences in factor means and factor structure between groups. Br J Mat Stat Psychol. 1974;27:229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF. Spurious genetic associations. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61 (10):1121–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager IB, Ngo L, Hanrahan JP. Maternal smoking during pregnancy. Effects on lung function during the first 18 months of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(3):977–983. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Rice F, Hay D, Boivin J, Langley K, van den Bree M, Rutter M, Harold G. Prenatal smoking might not cause attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a novel design. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Kistner EO, Pine DS, Biesecker G, Pickett KE, Skol AD, et al. Interaction of prenatal exposure to cigarettes and MAOA genotype in pathways to youth antisocial behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(9):928–937. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Pickett KE, Cook E, Jr, Benowitz NL, Leventhal BL. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and severe antisocial behavior in offspring: a review. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):966–974. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Pickett KE, Middlecamp MK, Walton LL, Tenzer P, Leventhal BL. Pregnant smokers who quit, pregnant smokers who don’t: does history of problem behavior make a difference? Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(12):2449–2460. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Pickett KE, Kasza KE, Loeber R. Is prenatal smoking associated with a developmental pattern of conduct problems in young boys? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(4):461–467. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000198597.53572.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Tager IB, Van Vunakis H, Speizer FE, Hanrahan JP. Maternal smoking during pregnancy, urine cotinine concentrations, and birth outcomes. A prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(5):978–988. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.5.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Brzustowicz LM. MAOA and the “cycle of violence:” childhood abuse and neglect, MAOA genotype, and risk for violent and antisocial behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(7):684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F, Tian XC, Du F, Kubota C, Taneja M, Dinnyes A, Dai Y, Levine H, Pereira LV, Yang X. Aberrant patterns of X chromosome inactivation in bovine clones. Nat Genet. 2002;31(2):216–220. doi: 10.1038/ng900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccolillo M. Gender and the development of conduct disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zoccolillo M, Paquette D, Azar R, Cote S, Tremblay RE. Parenting as an important outcome of conduct disorder in girls. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior and violence among girls. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. pp. 242–261. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Impulsive unsocialized sensation seeking: the biological foundations of a basic dimension of personality. In: Bates JE, Wachs TD, editors. Temperament: individual differences at the interface of biology and behavior. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. An alternative five-factorial model. In: Raad BDMP, editor. Big Five Assessment. Hogrefe and Huber; Ashland, OH: 2002. pp. 377–396. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Noll RB, Ham HP, Fitzgerald HE, Sullivan LS. Assessing antisociality with the Antisocial Behavior Checklist: Reliability and validity studies. (Unpublished manuscript) 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Zung BJ. Evaluation of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) in assessing lifetime and recent problems. J Clin Psychol. 1982;38(2):425–439. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198204)38:2<425::aid-jclp2270380239>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]