Abstract

Approximately 10%–15% of couples are infertile, and a male factor is involved in almost half of these cases. This observation is due in part to defects in spermatogenesis, and the underlying causes, including genetic abnormalities, remain largely unknown. Until recently, the only genetic tests used in the diagnosis of male infertility were aimed at detecting the presence of microdeletions of the long arm of the Y chromosome and/or chromosomal abnormalities. Various other single-gene or polygenic defects have been proposed to be involved in male fertility. However, their causative effects often remain unproven. The recent evolution in the development of whole-genome-based techniques and the large-scale analysis of mouse models might help in this process. Through knockout mouse models, at least 388 genes have been shown to be associated with spermatogenesis in mice. However, problems often arise when translating this information from mice to humans.

Keywords: genetic causes, gene, male infertility, spermatogenesis

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the inability to conceive after at least 1 year of regular and unprotected intercourse, affects approximately 10%–15% of couples.1, 2 It is estimated that a male factor is partially responsible for the fertility problems in approximately half of the couples. In this review, we will focus on those cases where spermatogenesis is deficient. Problems during spermatogenesis are reflected in a lower or absent production of spermatozoa and are described by routine semen analysis using terms such as ‘azoospermia', ‘oligozoospermia', ‘teratozoospermia' or ‘asthenozoospermia', or a combination of the last three (‘oligoasthenoteratozoospermia'). Because the main objective of this paper is to discuss ‘spermatogenic failure', we focus here on non-obstructive causes of male infertility and not on patients in whom sperm cells are produced but fail to reach their destination, i.e., obstructive azoospermia.

The underlying cause of these abnormalities in sperm production can either be acquired, congenital, or both. Currently, it is estimated that in approximately 40% of men, the diagnosis remains to be elucidated.3 In view of assisted reproductive techniques, it is especially important to gain information about the genetic causes of male infertility, as these defects can be transmitted across generation(s).

Routine tests

Currently, routine genetic analyses in the clinical diagnosis of non-obstructive azoospermia or oligozoospermia are limited to the investigation of the presence microdeletions of long arm of the Y chromosome (Yq) and/or chromosomal abnormalities. One of the first genetic tests to be performed in patients with severe idiopathic male infertility is karyotype analysis. Karyotype abnormalities are detected in ∼5% of patients with fertility problems, and this prevalence increases to >13% when only considering men with azoospermia.4, 5, 6 Most of the chromosomal abnormalities involve the sex chromosomes, with Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) being the most commonly detected karyotype abnormality in infertile men.7 The vast majority of patients with the non-mosaic form of Klinefelter syndrome are azoospermic. Yet, a recent review showed that mature spermatozoa can be detected in ∼44% of these patients.8 It is suggested that some foci with residual spermatogenesis might be present and that these foci are derived from normal 46,XY spermatogonia.9, 10 Multiple studies have also shown that the majority of sperm cells have a normal haploid chromosomal content.10, 11

Besides numerical abnormalities, structural defects are also detected 5–10 times more frequently in infertile men.4, 12 The formation of normal bivalents during meiosis is disrupted in patients with structural abnormalities (mainly with respect to translocations), leading to the expectation of impaired meiosis and a maturation arrest of spermatogenesis. However, in most of the patients with structural changes in the chromosome structure, oligozoospermia is observed. Therefore, it is also not surprising that the frequency of Robertsonian translocations, reciprocal translocations and inversions is higher in men with oligozoospermia compared with azoospermic men and men in the general population.12

It is also well known that Yq microdeletions are associated with male infertility. In 1992, Ma et al.13 reported the first Yq microdeletions. Since then, over 90 papers have been published describing the frequency of Yq microdeletions in different patients and population groups. A re-evaluation of the literature, including >13 000 infertile men, showed that the prevalence of Yq microdeletions is ∼7.4%. In an azoospermic population, the prevalence is higher (9.7%), while in oligozoospermic men, the prevalence is 6.0% (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of Yq microdeletions in patients with azoospermia or oligozoospermia. The group total also includes patients with undefined or unclassified semen parameters.

| Total | Deletions | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azoospermia (n) | 3157 | 305 | 9.7 |

| Oligozoospermia (n) | 3473 | 209 | 6 |

| Total (n) | 13 097 | 969 | 7.4 |

Abbreviation: Yq, long arm of the Y chromosome.

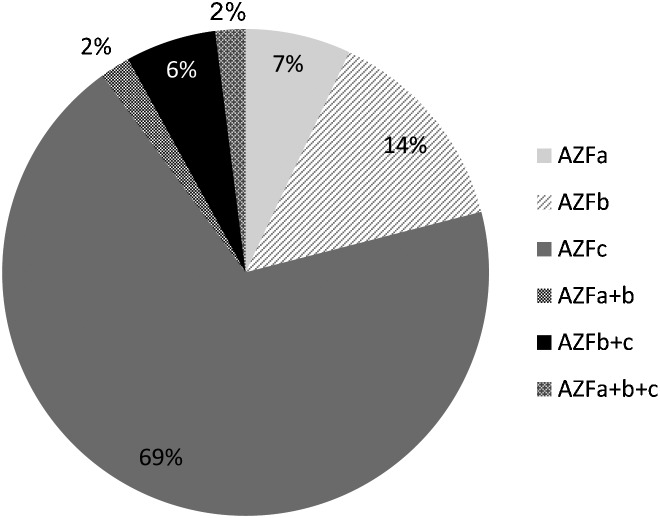

The Yq contains three ‘azoospermia factor (AZF)' regions: AZFa, AZFb and AZFc. Deletions of the complete AZFc region are most frequently detected (69%), followed by deletions of the AZFb region (14%) and deletions of the AZFa region (6%) (Figure 1). However, some papers report aberrant deletion patterns that were not confirmed. Consequently, the actual frequencies of AZF deletions in different patient groups might be slightly smaller, compared to the numbers deducted from all published papers. Furthermore, at least 12 AZFa+b deletions were reported. These deletions cannot be explained from the repeat structures present on the Yq, and their relevance remains doubtful. However, not all of the Yq microdeletions can be explained by non-allelic homologous recombination.14

Figure 1.

Distribution of Yq microdeletions among the three AZF regions. AZF, azoospermia factor; Yq, long arm of the Y chromosome.

The current guidelines for the detection of Yq microdeletions recommend the use of two markers in each AZF region in two multiplex PCR reactions. Each PCR reaction also has to include a marker for sex-determining region Y (SRY), located on the short arm of the Y chromosome, and a marker for ZFX/ZFY, a gene located on the X and Y chromosomes.15 Furthermore, for each test, positive (normal male), negative (normal female) and no template (water) controls should be included.

Deletions encompassing the complete AZFa or AZFb region are always associated with the complete absence of mature spermatozoa upon testicular biopsies. At the testicular level, the majority of the patients with an AZFa deletion have a Sertoli cell-only syndrome, while the most common phenotype among patients with an AZFb deletion is a maturation arrest of spermatogenesis.16 For both patient groups, no sperm cells are left in their testis. Consequently, the diagnosis of an AZFa or AZFb deletion has important consequences for adequate counselling of the patients; a testicular biopsy is unnecessary because of the absence of sperm cells for intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). One rare exception has been described in which the complete AZFb region was absent in a severe oligozoospermic man.17 However, it is interesting to note that testicular sperm extraction in this man was unsuccessful in retrieving spermatozoa, further underlying the negative predictive value of the complete AZFb deletion for testicular sperm retrieval in azoospermic men.

The complete absence of the AZFc region, in contrast, causes a more heterogeneous phenotype, ranging from azoospermia to severe oligozoospermia (<5 million spermatozoa per ml). We estimated that spermatozoa could be found in approximately 70% of patients with an AZFc deletion.18 Consequently, for these patients, ICSI remains possible. Because sons conceived after ICSI have a high chance of having impaired spermatogenesis, appropriate genetic counselling is necessary to explain the consequences of ICSI and to inform these men of the possible alternatives or additional treatments, such as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis to select female embryos.

Screening for the presence of gr/gr deletions, which are partial deletions of the AZFc regions, is not performed in most of the routine genetic testing laboratories. Other reports, including one from our group, have shown an increased incidence of gr/gr deletions in men with fertility problems.19, 20, 21 However, these gr/gr deletions are also detected in men with normal semen parameters and should therefore be considered more as a risk factor for male infertility rather than a causative factor. Besides these gr/gr deletions, which are associated with decreased sperm parameters, other partial deletions can be detected on the Y chromosome.22 These include b1/b3 deletions and b2/b3 deletions, which are presumably neutral changes. Furthermore, duplications and other structural changes are observed in the AZFc region of the Y chromosome.22 From several publications, it is obvious that the distribution of these alterations is not equal among different populations,21, 22 which makes the interpretation of the consequences of these changes a challenge.

Single-gene defects versus polygenic causes

Until recently, single-gene defects were the focus of most of the published studies. However, it is obvious that in some of the patients, a combination of mutations or polymorphisms might cause fertility problems. Potentially, a combination of congenital/genetic and environmental factors might eventually be recognized as the cause of fertility problems. Yet, the number of patients affected by a single-gene defect remains unclear. Table 2 gives an overview of genes that have been tested by one or more research groups. However, the majority of these studies fail to identify a mutation that is associated with the examined phenotype.

Table 2. Genes tested with consideration of human non-syndromic spermatogenesis or sperm defects, with special emphasis on genes tested at the DNA level.

| Patients | Phenotype | One study | Multiple studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azoospermia | Maturation arrest of spermatogenesis | DNMT3L, FKBP6, FKBPL, MEI1, MSH4, STRA8, TAF7L | RBMY a, SYCP3 | 36–39, 41, 45, 74, 75 |

| Sertoli cell-only syndrome | BPY2 a, DBY a, USP9Y a | 76–83 | ||

| Not defined | ART3, PRDM9, SOHLH1, TAF7L, ZNF230 | 42,85–87 | ||

| Abnormal semen parameters | Teratozoospermia | CSNK2A2, GOPC, HRB, PICK1, SPATA16, eNOS | AURKc, DPY19L2 | 23, 24, 27–30, 85 |

| Asthenozoospermia | ADCY10, CATSPER3/4, DNAI1, DNAH5, DNAH11, eNOS, HFE, PLA2G6, SPAG16, TNFalpha A, TNFR1, TNFR2 | AKAP3/4, CATSPER1/2 | 33–37, 89–96 | |

| OAT or not defined | DNMT3b, eNOS, HIWI2/3, OAZ3, PON1/2, SCA1 | CDY1 a, CYP1A1, DAZ a, DAZL, ESR1/2, GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1, HSFY a, KLHL10, POLG, PRM1/2, TNP1/2, TSPY a | 19, 97–118 | |

| Infertile men (undefined or mixed) | FKBPL, GAMT, H1FNT, H2BFWT, HFE, HSP90, MS, MTR, MTRR, NANOS2, NANOS3, NR5A1, NRIP1, PUM2, NALP14, SLC6A8, TSSK2, TSSK6, UTP14C | APOB, AR, BOULE, c-KIT, KITLG CYP19A1, CREM, DDX25, FAS, FASLG, FKBP6, FSH, FSHR, LH, LHCGR, MTHFR, SHBG, UBE2B, USP26, YBX2 (=MSY2) | 19, 102, 119–151 |

Abbreviation: OAT, oligoasthenoteratozoospermia.

These genes are located in the AZF regions on the Y chromosome. For some of the Yq genes, gene-specific deletion and/or mutation screening has been performed (USP9Y, DBY). For other genes, this method of screening was impossible because of the multicopy nature of the genes; for some of these genes, the copy number has been determined in infertile men.117, 151

Single-gene defects

We believe that, especially in men with ‘well-defined' and specific defects during sperm production, mutations in a single-gene might be responsible for the observed phenotype.

In this respect, rare cases with a well-defined sperm abnormality, such as globozoospermia or macrocephalic sperm cells, are interesting subjects for study. Indeed, the mutations in these patient groups have already been reported. In two families with multiple infertile men caused by globozoospermia, Dam et al.23 and Liu et al.24 detected mutations in the SPATA16 (spermatogenesis associated protein 16) and PICK1 (protein interacting with c kinase 1) genes, respectively. Dam et al.23 detected a homozygous mutation in the SPATA16 gene in three brothers of an Ashkenazi Jewish family. This mutation consists of an amino-acid substitution and confers the removal of a splice site. The subsequent screening for mutations in the SPATA16 gene in 29 patients with globozoospermia failed to identify other changes in this gene. The SPATA16 gene is presumably involved in the formation of the acrosome. It was observed that this protein translocates from the Golgi to the acrosome during spermiogenesis.25 In the second study by Liu et al.,24 a potential homozygous mutation was detected in the PICK1 gene of a single patient with globozoospermia from consanguineous parents. This change was absent in 100 normozoospermic Chinese controls.24 Moreover, PICK1 is also presumably involved in the formation of the acrosome.26 Although the gene showed a ubiquitous expression pattern, Xiao et al.26 showed that the major abnormality in Pick1−/− mice was infertility. In two publications concerning patients with globozoospermia, a homozygous deletion was detected on chromosome 12 encompassing the DPY19L2 gene.27, 28 One paper described a 200-kb deletion in a consanguineous Jordanian family and three unrelated patients,28 while the second research group detected the homozygous deletion in 15 out of 20 globozoospermic men that were tested using single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays.27 Additionally, in patients with large-headed polyploid multiflagellar sperm cells, a mutation was detected in the AURKc (aurora kinase c) gene, which is involved in chromosome segregation and cytokinesis. The typical phenotype of large headed sperm cells is especially detected in North African men, where the carrier frequency of the mutation is estimated to be 1/50.29, 30

Visser et al.31 analysed 30 patients with isolated asthenozoospermia for the presence of mutations in nine genes that were selected on the basis of the phenotype observed in knockout mouse models. They identified four CATSPER genes, which form the ion channel essential for the calcium influx during sperm capacitation. The genes GAPDHS, PLA2G6 and ADCY10 code for enzymes specifically expressed in sperm, and SLC9A10 is a sodium hydrogen exchanger.31 A total of 10 potential mutations were detected in seven of these genes (ADCY10, AKAP4, CATSPER1, CATSPER2, CATSPER3, CATSPER4 and PLA2G6), yet all of the changes were heterozygous alterations. However, three patients had multiple changes in the investigated genes. Previous studies reported a man with partial deletions in the AKAP3 and AKAP4 genes that caused isolated asthenozoospermia.32 In addition, mutations in the CATSPER1 gene and deletion of the CATSPER2 gene had been previously associated with asthenozoospermia.33, 34, 35 However, in most of the patients, a reduced sperm number and an increased number of morphological abnormal spermatozoa were also detected.

Another interesting patient group is men with a maturation arrest of spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis can arrest at different stages, although primarily, an arrest during meiosis is observed. Therefore, abnormalities in genes essential for meiosis are possible candidates for the defect in spermatogenesis. Yet, as suggested above, chromosomal abnormalities can also be the underlying cause of the failure to complete meiosis. This idea emphasizes the need to perform karyotype analysis before or in parallel with testing for the presence of gene mutations. Different groups have investigated the involvement of the SYCP3 (synaptonemal complex gene 3) gene in male infertility.36, 37, 38 Miyamoto et al.36 detected a single change in two patients, which was predicted to alter the function of the protein. Two studies have investigated the SYCP3 gene for the presence of mutations in association with recurrent miscarriages.39, 40 Three patients (two women and a man) were described with changes in the SYCP3 gene that were potentially linked to their problems, i.e., maintaining a pregnancy, which might be due to an abnormal chromosomal constitution of the foetus.39, 40 The TAF7L gene has also been studied in relation to the maturation arrest of spermatogenesis or azoospermia.41, 42 In the first study, four non-synonymous changes were detected with equal frequencies in the patient and control groups.41 The second study identified three of these four changes in their patient population and concluded that one of the changes present in exon 13 could be linked with azoospermia. The X-linked transcription factor TAF7L translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus during meiosis,43 suggesting a function during meiosis. Yet, subsequent studies in mice showed that sperm cells were still produced, although at a lower rate, with abnormal morphology and motility.44 This result indicated that patients with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia would have been a more appropriate group to screen.

In another study, Sato et al.45 looked at the presence of mutations in the meiosis defective 1 (MEI1) gene. This gene was selected based on knockout mouse models that showed a meiotic arrest due to impaired chromosome synapsis.46 Two synonymous SNPs were potentially associated with maturation arrest of spermatogenesis in Americans of European origin but not in Israelis. One SNP, resulting in a single amino-acid change, was detected in one patient and not in the controls. However, due to the low number of patients and controls analysed, the physiological meaning of this amino acid change could not be proven, because it failed to reach statistical significance.

These studies in patients with maturation arrest of spermatogenesis illustrate some of the pitfalls and obstacles that should be considered when investigating genetic causes of spermatogenesis defects or when drawing conclusions from the published studies.

The number of patients analysed is often too low to draw solid conclusions. The observation is often intrinsic to patient groups under investigation; it is hard to find large numbers of patients with a specific phenotype.

The ethnicity of patients and controls should match. Some SNPs are common in certain population groups, but rare or absent in other groups. However, sometimes it is hard to exclude that either the patient or the control has ‘foreign' ancestors.

Often, no functional studies have been performed. Therefore, it is hard to predict the consequences of the observed changes, especially considering amino acid substitutions.

When analysing data, one should also consider the consequence of heterozygous versus homozygous changes. Even when functional analyses show that the function of a mutant protein is altered, a second ‘normal' protein might compensate for the loss. Compensation has been observed in mouse studies where heterozygous mice are often fertile. Only a homozygous knockout of a gene completely disrupts the function of the gene product.

One should also consider that the function of genes might be different when comparing the mice and humans.

Furthermore, in knockout mice, often a large part of the gene has been removed. Thus, the consequences of a small in-frame deletion or amino acid substitution might be less severe than that predicted from the mouse study. This phenomenon was observed in studies investigating changes in the SYCP3 gene, where mutations were compatible with fertility (but associated with miscarriages).39, 40 Knockout male mice were completely sterile, but in these mice, an important fraction of the gene was missing.47

When no knockout mouse studies are available, the phenotype caused by mutations might be predicted based on the expression pattern of the gene of interest. Yet again, caution should be taken. As shown with the TAF7L gene, the observed phenotype could be less severe than that predicted from the expression pattern.

From these ‘pitfalls', it is obvious that even ‘specific' phenotypes should be handled with care, and even for these groups, multiple factors might be involved in the aetiology of the disease. When analysing unselected groups of patients, it is even more important to consider the aforementioned difficulties. The number of papers describing mutations in genes that are clearly associated with the observed fertility problems in patients remains severely limited.

Polygenic causes

As mentioned above, single-gene defects are especially expected in patients with a ‘specific' phenotype. Yet, the majority of patients visiting fertility clinics for male factor infertility suffer from poor semen parameters. For men with unexplained oligozoospermia, it is difficult to predict whether a defect in a single gene causes the fertility problems. Indeed, the cause might be multifactorial and include defects in one or more genes and potentially be combined with environmental factors. Each factor on its own can be considered as a ‘risk factor'. In extremes, Sertoli cell-only syndrome (the complete absence of germ cells in the testicular tissue) could also be caused by an accumulation of risk factors. Yet in these patients, also single-gene defects can be expected, for instance, in genes essential to maintain the stem cell pool of spermatogonia.

Two well-studied risk factors are the gr/gr deletions and MTHFR gene polymorphisms. The gr/gr deletions have already been discussed in a previous section. We believe that the impact of gr/gr deletions is dependent on the genetic background and is potentially under the influence of environmental factors. Consequently, the patients will still have normal sperm counts or be classified as oligozoospermic. Therefore, it is essential to gain more insight into these genetic factors that should be considered as risk factors because the presence of a single, isolated risk factor might have only a small influence on spermatogenesis. Consequently, when analysing the controls, one might (incorrectly) conclude that this factor/polymorphism has no influence on male infertility. It will be an ongoing challenge to map genetic risk factors that might have an impact on the efficiency of sperm production. Again, we should consider the same interpretation errors that are encountered with the identification of single-gene defects. In particular, differences in ethnicity should be considered. As with the C677T SNP, the background in which the MTHFR gene is expressed might be important for the consequences of the SNP. The MTHFR gene is essential for folate metabolism. It is suggested that in countries with a low dietary intake of folates, the homozygous C677T polymorphism might be associated with male infertility, as folates are essential for DNA methylation.48 Tüttelmann et al.19 performed a meta-analysis of eight published studies that showed a clear association between homozygous change and decreased spermatogenesis. Alternatively, some SNPs might be more common in ethnic subpopulations without affecting infertility. In the case of gr/gr deletions, it was observed that these deletions are fixed on the Y haplogroups Q1 and D2b, which are present in high frequencies in China and Japan, respectively.49, 50, 51 It is supposed that protective mechanisms are present on these Y chromosomes that counteract with the gr/gr deletions.

The development of whole-genome approaches, as described in the next paragraph, will enable the identification of changes in multiple genes simultaneously and will thus facilitate the identification of polygenic causes. Yet, the interpretation of the data will be the most difficult part of these studies.

Implementation of new techniques

The implementation of whole-genome approaches, such as SNP arrays, array comparative genomic hybridisation analysis and whole-genome or exome analysis through next generation sequencing, will enable researchers to analyse multiple genes in parallel. These studies will be useful in identifying polygenic causes and single-gene defects. This approach also has the advantage of avoiding the selection bias of genes to be included in studies on (in)fertility. The current studies are primarily based on what is already known about genes from mouse studies.

SNP arrays have already been used in studying familial cases of male infertility. Dam et al.,23 for instance, were able to identify a mutation in the SPATA16 gene after minimizing the region of interest through linkage analysis by SNP arrays. Nevertheless, large families with multiple fertile and infertile men are difficult to find.

Until now, a single pilot study has been published in which the authors performed a ‘genome-wide SNP association study' to identify SNPs that were linked to male infertility.52 A follow-up study showed that some of the SNPs might be associated with azoospermia or oligozoospermia.53 Yet, this study failed to identify ‘real causes' of male infertility, but rather, identified factors that were only present in infertile males, and not in the controls. These SNPs could be considered as potential risk factors.

Through array comparative genomic hybridisation, deletions or increased copy numbers can be detected in the whole genome. The main limitation of array comparative genomic hybridisation is the resolution of the platform used, meaning that small rearrangements might be missed. Moreover, mutations or translocations cannot be detected. One study described the involvement of copy number variations in patients with disorders in sexual development.54 Although the majority of these patients also face fertility problems, spermatogenesis failure is not the only phenotypic abnormality in these patients.

To our knowledge, whole-exome or whole-genome analysis through next generation sequencing has not been described in relation to the study of male infertility. Again, the interpretation of the data will be difficult. Therefore, it is important to select well-defined and extremely specific patient groups in which single-gene defects are more likely.

Whole-genome approaches have the advantage that defects can be detected in genes with an unknown function, thereby avoiding the manual selection of genes based on their known expression pattern or described phenotype in knockout mouse studies. Whole-genome sequencing techniques also represent a potentially well-suited approach to characterize complex spermatogenic impairment phenotypes resulting from disturbances in multiple genes. Furthermore, novel insights into epigenetic mechanisms regulating spermatogenesis might be acquired. Epigenetic deviations have been shown to be potentially responsible for male infertility; examples are an abnormal protamine 1/protamine 2 ratio and aberrant methylation patterns in DAZL and CREM.55, 56

First, more insight needs to be gained into the function of the genes that are involved in spermatogenesis. However, during spermatogenesis, numerous genes are expressed under the influence of hormones, but also of autocrine, paracrine and juxtacrine factors between the various testicular compartments, making it impossible to model this process completely in vitro.57 Therefore, many models for studying the role of genes in spermatogenesis have been used. The mouse is the model organism of choice for this purpose, mainly because mouse spermatogenesis is comparable to that in humans. Furthermore, mice have a short reproductive cycle with large litter sizes, are not expensive to accommodate and their embryos are easy to manipulate at the genetic level.58

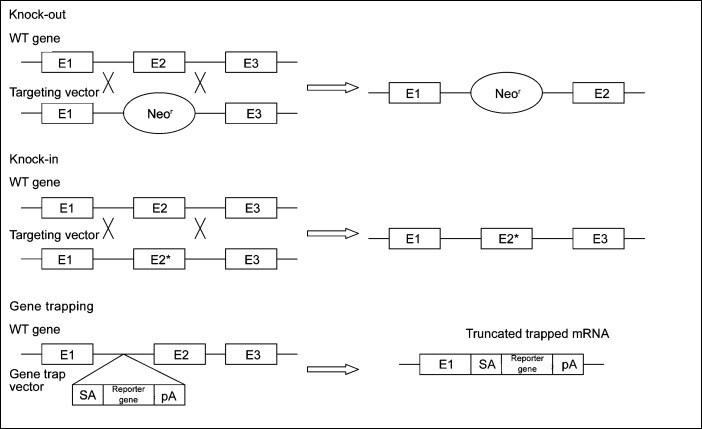

Mouse models

The technique primarily used to study a gene function in vivo is the generation of knockout mouse models, where a gene is inactivated or ‘knocked out' by replacing or disrupting it (Figure 2). Consequently, the role of the defective gene(s) can be determined. In the Mouse Genome Informatics database (http://www.informatics.jax.org/), over 388 knockout mouse models with impaired spermatogenesis are currently described. The technique to generate knockout mouse models is based on the reverse genetic approach; the function of a gene can be predicted by alterations of the expression of a specific gene, followed by the evaluation of the phenotypic outcome. However, the ablation of a critical gene can result in unexpected embryonic death, making the analysis of the role of this gene in spermatogenesis impossible. Conditional and inducible knockout models can be made to prevent this. In conditional knockouts, the gene is inactivated only in specific tissues, using Cre–LoxP or Flp–FRT site-specific recombination systems. In inducible knockout models, the gene of interest is fused with an antibiotic sensitive gene such that it will become disrupted when the antibiotic is administered.59 A recent example using conditional knockout mice was applied to determine the testicular function of the transcription factor Gata4 in adult mice.60 Gata4 knockout mice died from defects in ventral morphogenesis and heart development at embryonic day 9.5.61 Therefore, Cre–LoxP recombination in conjunction with Amhr2–Cre was used to delete the GATA4 gene only in the Sertoli cells, and consequently, the function could be studied at a later stage.61 At 6 months, these knockout mice showed decreased sperm counts and sperm motility, resulting in testicular atrophy and loss of fertility.61

Figure 2.

Scheme of knockout, knockin and gene trapping methodologies. pA, plasminogen activator; SA, splice acceptor; WT, wild type; E, exon.

A variant of the knockout approach is the creation of knockin models in which mutations are introduced in the genome by replacing the original gene by its mutant version using homologous recombination (Figure 2).

In the International Knockout Mouse Consortium, different groups collaborate to mutate all of the protein-encoding genes in the mouse using a combination of gene trapping and gene targeting in C57BL/6 mouse embryonic stem cells. Gene trapping is a high-throughput method in which gene trap cassettes are inserted either randomly across the genome or at a specific site, resulting in gene ablation62, 63 (Figure 2). The International Knockout Mouse Consortium includes the following programs: the Knockout Mouse Project (USA), the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (Europe), the North American Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Project (Canada) and the Texas A&M Institute for Genomic Medicine (USA) (http://www.knockoutmouse.org/).

A disadvantage of the reverse genetic approach is that prior knowledge of the gene's function is needed, and therefore, only genes with an expected role in spermatogenesis will be detected. This is not the case in the forward genetic or phenotypic-driven approach, which starts with the selection of a model with a phenotype of interest, and subsequently determines the underlying genetic cause. As described above, gene trapping disrupts genes at random. Another forward genetic approach is whole-genome mutagenesis in which high rates of point mutations are randomly introduced throughout the whole genome. This approach is primarily performed using the alkylating agent N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU), which causes mutations in all cells, particularly in premeiotic spermatogonial stem cells. After the selection of mice with the desired phenotype, the causal mutation can be identified through linkage analysis, followed by sequencing of the candidate genes or the currently preferred method of whole-genome sequencing. Instead of null alleles, single base-pair substitutions are generated, which adequately reflect the disease-causing mutations that are predicted in human and can also help in determining critical domains for protein function. The first large-scale ENU mouse mutagenesis programmes were implemented at the end of 1996 in Germany and the United Kingdom.64, 65 In 2002, the Reproductive Genomics Program was set up at the Jackson Laboratory to develop mouse models of infertility using ENU mutagenesis (http://reproductivegenomics.jax.org). Currently, 38 models expressing male infertility have been generated in this programme, and the chromosomal location is known for 30 of them.66 Through this program and in subsequent individual studies aiming to characterize the underlying genetic defect of the observed phenotypes, several novel genes were identified that cause male infertility. These genes include Brwd1, which is necessary for the completion of gametogenesis;67 Capza3, which is involved in the removal of excess cytoplasm during spermiation;68 and eIF4G3, a translation initiation factor.69 Furthermore, mutations in Nsun7 result in a rigid flagellar midpiece of the sperm cells that causes decreased progressive motility70, 71 and mutations in Hei10 impair alignment of the chromosomes at the metaphase plate in both spermatocytes and oocytes.72

These mouse studies will provide useful information about the function of proteins involved in spermatogenesis. Furthermore, we might obtain information concerning the consequences of the mutation or deletion of the corresponding genes. However, as mentioned above, caution should be taken in translating the results found in mice to humans. Some biological processes such as the process of the sperm–egg interaction can be different between mice and humans.73 Furthermore, similar genes could have different functions. Whereas the knockout of a certain gene results in infertility in mice, the function of one gene could compensate for another in humans.

Conclusions

Despite substantial efforts over the last decade, the genetic causes of spermatogenetic failure still remain largely unknown. It has been estimated that more than 2300 genes play a role in spermatogenesis.59 Mutations in each of these genes could theoretically cause male infertility. Only a few of these genes have been investigated in humans, and most of the detected alterations could not be demonstrated to cause infertility. Through the use of knockout mouse models, 388 genes have already been shown to be involved in spermatogenesis, but translating these results to humans should be done with care. One reason for this caution is that a large part of male infertility in humans is not caused by monogenic homozygotic mutations except for well-defined cases such as globozoospermia. Considering that thousands of genes are involved in male fertility, it could be possible that innumerable combinations of heterozygous base pair changes or risk factors could cause male infertility. Thus, the molecular diagnosis of infertility would be difficult with the current available technologies. The recent evolution in the development of whole genome-based techniques and the large-scale analysis of mouse models will hopefully help to identify more infertility-related mutations and risk factors. In addition, epigenetics has created a promising avenue in the field of male infertility. The development of an adequate in vitro human model for spermatogenesis would also be helpful.

The authors declare no competing financial interets.

References

- Evers JL. Female subfertility. Lancet. 2002;360:151–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devroey P, Fauser BC, Diedrich K. Evian Annual Reproduction (EVAR) Workshop Group 2008 Approaches to improve the diagnosis and management of infertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:391–408. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz C. Male infertility: pathogenesis and clinical diagnosis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlin A, Raicu F, Gatta V, Zuccarello D, Palka G, et al. Male infertility: role of genetic background. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:734–45. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan RI, O'Bryan MK. Clinical review: state of the art for genetic testing of infertile men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1013–24. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Assche E, Bonduelle M, Tournaye H, Joris H, Verheyen G, et al. Cytogenetics of infertile men. Hum Reprod. 1996;11 Suppl 4:1–24. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.suppl_4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresta C, Garolla A, Bartoloni L, Bettella A, Ferlin A. Genetic abnormalities among severely oligospermic men who are candidates for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:152–66. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton G, Hamilton M, Maheshwari A. Should non-mosaic Klinefelter syndrome men be labelled as infertile in 2009. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:588–97. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciurano RB, Luna Hisano CV, Rahn MI, Brugo Olmedo S, Rey Valzacchi G, et al. Focal spermatogenesis originates in euploid germ cells in classical Klinefelter patients. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2353–60. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rives N, Joly G, Machy A, Siméon N, Leclerc P, et al. Assessment of sex chromosome aneuploidy in sperm nuclei from 47,XXY and 46,XY/47,XXY males: comparison with fertile and infertile males with normal karyotype. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:107–12. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levron J, Aviram-Goldring A, Madgar I, Raviv G, Barkai G, et al. Sperm chromosome analysis and outcome of IVF in patients with non-mosaic Klinefelter's syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:925–29. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantot-Bastaraud S, Ravel C, Siffroi JP. Underlying karyotype abnormalities in IVF/ICSI patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16:514–22. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Sharkey A, Kirsch S, Vogt P, Keil R, et al. Towards the molecular localisation of the AZF locus: mapping of microdeletions in azoospermic men within 14 subintervals of interval 6 of the human Y chromosome. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:29–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling MA. Copy number variation on the human Y chromosome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2008;123:253–62. doi: 10.1159/000184715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni M, Bakker E, Krausz C. EAA/EMQN best practice guidelines for molecular diagnosis of y-chromosomal microdeletions. State of the art 2004. Int J Androl. 2004;27:240–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz C, Quintana-Murci L, McElreavey K. Prognostic value of Y deletion analysis: what is the clinical prognostic value of Y chromosome microdeletion analysis. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1431–4. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.7.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longepied G, Saut N, Aknin-Seifer I, Levy R, Frances AM, et al. Complete deletion of the AZFb interval from the Y chromosome in an oligozoospermic man. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2655–63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffs K, Lissens W, Tournaye H, van Steirteghem A, Liebaers I. The choice and outcome of the fertility treatment of 38 couples in whom the male partner has a Yq microdeletion. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1887–96. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tüttelmann F, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Nieschlag E, Simoni M. Gene polymorphisms and male infertility—a meta-analysis and literature review. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;15:643–58. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser L, Westerveld GH, Korver CM, van Daalen SK, Hovingh SE. Y chromosome gr/gr deletions are a risk factor for low semen quality. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2667–73. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffs K, Lissens W, Tournaye H, Haentjens P. What about gr/gr deletions and male infertility? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:197–209. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Costa P, Gonçalves J, Plancha CE. The AZFc region of the Y chromosome: at the crossroads between genetic diversity and male infertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:525–42. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam AH, Koscinski I, Kremer JA, Moutou C, Jaeger AS, et al. Homozygous mutation in SPATA16 is associated with male infertility in human globozoospermia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:813–20. doi: 10.1086/521314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Shi QW, Lu GX. A newly discovered mutation in PICK1 in a human with globozoospermia. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:556–60. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Lin M, Xu M, Zhou ZM, Sha JH. Gene functional research using polyethylenimine-mediated in vivo gene transfection into mouse spermatogenic cells. Asian J Androl. 2006;8:53–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2006.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao N, Kam C, Shen C, Jin W, Wang J, et al. PICK1 deficiency causes male infertility in mice by disrupting acrosome formation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:802–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI36230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbuz R, Zouari R, Pierre V, Ben Khelifa M, Kharouf M, et al. A recurrent deletion of DPY19L2 causes infertility in man by blocking sperm head elongation and acrosome formation. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:351–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koscinski I, Elinati E, Fossard C, Redin C, Muller J, et al. DPY19L2 deletion as a major cause of globozoospermia. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich K, Soto Rifo R, Faure AK, Hennebicq S, Ben Amar B, et al. Homozygous mutation of AURKC yields large-headed polyploidspermatozoa and causes male infertility. Nat Genet. 2007;39:661–5. doi: 10.1038/ng2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich K, Zouari R, Harbuz R, Vialard F, Martinez D, et al. The Aurora Kinase C c.144delC mutation causes meiosis I arrest in men and is frequent in the North African population. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1301–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser L, Westerveld GH, Xie F, van Daalen SK, van der Veen F, et al. A comprehensive gene mutation screen in men with asthenozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1020–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccetti B, Collodel G, Estenoz M, Manca D, Moretti E, et al. Gene deletions in an infertile man with sperm fibrous sheath dysplasia. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2790–4. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avidan N, Tamary H, Dgany O, Cattan D, Pariente A, et al. CATSPER2, a human autosomal nonsyndromic male infertility gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:497–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Malekpour M, Al-Madani N, Kahrizi K, Zanganeh M, et al. Sensorineural deafness and male infertility: a contiguous gene deletion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007;44:233–40. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenarius MR, Hildebrand MS, Zhang Y, Meyer NC, Smith LL, et al. Human male infertility caused by mutations in the CATSPER1 channel protein. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:505–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T, Hasuike S, Yogev L, Maduro MR, Ishikawa M, et al. Azoospermia in patients heterozygous for a mutation in SYCP3. Lancet. 2003;362:1714–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14845-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffs K, Lissens W, Tournaye H, van Steirteghem A, Liebaers I. SYCP3 mutations are uncommon in patients with azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1019–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez J, Bonache S, Carvajal A, Bassas L, Larriba S. Mutations of SYCP3 are rare in infertile Spanish men with meiotic arrest. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:988–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffs K, Vandermaelen D, Tournaye H, Liebaers I, Lissens W. Mutation analysis of three genes in patients with maturation arrest of spermatogenesis and couples with recurrent miscarriages. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolor H, Mori T, Nishiyama S, Ito Y, Hosoba E, et al. Mutations of the SYCP3 gene in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffs K, Willems A, Lissens W, Tournaye H, van Steirteghem A, et al. The role of the testis-specific gene TAF7L in the etiology of male infertility. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:263–7. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinloye O, Gromoll J, Callies C, Nieschlag E, Simoni M. Mutation analysis of the X-chromosome linked, testis-specific TAF7L gene in spermatogenic failure. Andrologia. 2007;39:190–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2007.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointud JC, Mengus G, Brancorsini S, Monaco L, Parvinen M, et al. The intracellular localisation of TAF7L, a paralogue of transcription factor TFIID subunit TAF7, is developmentally regulated during male germ-cell differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1847–58. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Buffone MG, Kouadio M, Goodheart M, Page DC, et al. Abnormal sperm in mice lacking the Taf7l gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2582–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01722-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Miyamoto T, Yogev L, Namiki M, Koh E, et al. Polymorphic alleles of the human MEI1 gene are associated with human azoospermia by meiotic arrest. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:533–40. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby BJ, Reinholdt LG, Schimenti JC. Positional cloning and characterization of Mei1, a vertebrate-specific gene required for normal meiotic chromosome synapsis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2432067100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Liu JG, Zhao J, Brundell E, Daneholt B, et al. The murine SCP3 gene is required for synaptonemal complex assembly, chromosome synapsis, and male fertility. Mol Cell. 2000;5:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezold G, Lange M, Peter RU. Homozygous methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutation and male infertility. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1172–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repping S, Skaletsky H, Brown L van Daalen SK, Korver CM, et al. Polymorphism for a 1.6-Mb deletion of the human Y chromosome persists through balance between recurrent mutation and haploid selection. Nat Genet. 2003;35:247–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Zhang J, Li Y, Xia Y, Zhang F, et al. The b2/b3 subdeletion shows higher risk of spermatogenic failure and higher frequency of complete AZFc deletion than the gr/gr subdeletion in a Chinese population. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1122–30. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Ma M, Li L, Su D, Chen P, et al. Differential effect of specific gr/gr deletion subtypes on spermatogenesis in the Chinese Han population. Int J Androl. 2010;33:745–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston KI, Carrell DT. Genome-wide study of single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with azoospermia and severe oligozoospermia. J Androl. 2009;30:711–25. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.007971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston KI, Krausz C, Laface I, Ruiz-Castané E, Carrell DT. Evaluation of 172 candidate polymorphisms for association with oligozoospermia or azoospermia in a large cohort of men of European descent. Hum Reprod. 2010;6:1383–97. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannour-Louet M, Han S, Corbett ST, Louet JF, Yatsenko S, et al. Identification of de novo copy number variants associated with human disorders of sexual development. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Costa P, Nogueira P, Carvalho M, Leal F, Cordeiro I, et al. Incorrect DNA methylation of the DAZL promoter CpG island associates with defective human sperm. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2647–54. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanassy L, Carrell DT. Abnormal methylation of the promoter of CREM is broadly associated with male factor infertility and poor sperm quality but is improved in sperm selected by density gradient centrifugation. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2310–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Lamb DJ. Genetic dissection of mammalian fertility pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4 Suppl:s41–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb-nm-fertilityS41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamsai D, O'Bryan MK. Mouse models in male fertility research. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:139–51. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamowski S, Aston KI, Carrell D. The use of transgenic mouse models in the study of male infertility. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2010;56:260–73. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2010.485244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrönlahti A, Euler R, Bielinska M, Schoeller EL, Moley KH, et al. GATA4 regulates Sertoli cell function and fertility in adult male mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;333:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita N, Bielinska M, Wilson DB. Wild-type endoderm abrogates the ventral development defects associated with GATA-4 deficiency in the mouse. Dev Biol. 1997;189:270–4. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman JM, Tsakiridis A, To C, Stanford WL. A wider context for gene trap mutagenesis. Methods Enzymol. 2010;477:271–95. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)77014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel RH, Soriano P. Gene trap mutagenesis in the mouse. Methods Enzymol. 2010;477:43–69. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)77013-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabe de Angelis M, Balling R. Large scale ENU screens in the mouse: genetics meets genomics. Mutat Res. 1998;400:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Nolan PM. Mouse mutagenesis-systematic studies of mammalian gene function. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1627–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.10.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard C, Pendola JK, Hartford SA, Schimenki JC, Handel MA, et al. New mouse genetic models for human contraceptive development. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;105:222–7. doi: 10.1159/000078192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipps DL, Wigglesworth K, Hartford SA, Sun F, Pattabiraman S, et al. The dual bromodomain and WD repeat-containing mouse protein BRWD1 is required for normal spermiogenesis and the oocyte–embryo transition. Dev Biol. 2008;317:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer CB, Inselman AL, Sunman JA, Bornstein S, Handel MA, et al. A missense mutation in the Capza3 gene and disruption of F-actin organization in spermatids of repro32 infertile male mice. Dev Biol. 2009;330:142–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Palmer K, Handel MA. Mutation of Eif4g3, encoding a eukaryotic translation initiation factor, causes male infertility and meiotic arrest of mouse spermatocytes. Development. 2010;137:1699–707. doi: 10.1242/dev.043125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L, Ching YH, Farias MF, Hartford S, Howell G, et al. Random mutagenesis of proximal mouse Chromosome 5 uncovers predominantly embryonic lethal mutations. Genome Res. 2005;15:1095–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.3826505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T, Marquez B, Suarez S, Schimenti J. Sperm motility defects and infertility in male mice with a mutation in Nsun7, a member of the Sun domain-containing family of putative RNA methyltransferases. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:376–82. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.058669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JO, Reinholdt LG, Motley WW, Niswander LM, Deacon DC, et al. Mutation in mouse hei10, an e3 ubiquitin ligase, disrupts meiotic crossing over. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Saunders PT. Mouse models of male infertility. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:790–801. doi: 10.1038/nrg911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Zhang S, Xiao C, Yang Y, Zhoucun A. Mutation screening of the FKBP6 gene and its association study with spermatogenic impairment in idiopathic infertile men. Reproduction. 2007;133:511–6. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunnotel O, Hiripi L, Lagan K, McDaid JR, de León JM, et al. Alterations in the steroid hormone receptor co-chaperone FKBPL are associated with male infertility: a case–control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Koh E, Suzuki H, Maeda Y, Yoshida A, et al. Alu sequence variants of the BPY2 gene in proven fertile and infertile men with Sertoli cell-only phenotype. Int J Urol. 2007;14:431–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YM, Lin YH, Teng YN, Hsu CC, Shinn-Nan Lin J, et al. Gene-based screening for Y chromosome deletions in Taiwanese men presenting with spermatogenic failure. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:897–903. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luddi A, Margollicci M, Gambera L, Serafini F, Cioni M, et al. Spermatogenesis in a man with complete deletion of USP9Y. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:881–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims LM, Ballantyne J. A rare Y chromosome missense mutation in exon 25 of human USP9Y revealed by pyrosequencing. Biochem Genet. 2008;46:154–61. doi: 10.1007/s10528-007-9139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz C, Degl'Innocenti S, Nuti F, Morelli A, Felici F, et al. Natural transmission of USP9Y gene mutations: a new perspective on the role of AZFa genes in male fertility. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2673–81. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Landuyt L, Lissens W, Stouffs K, Tournaye H, van Steirteghem A, et al. The role of USP9Y and DBY in infertile patients with severely impaired spermatogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:691–3. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.7.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Skaletsky H, Birren B, Devon K, Tang Z, et al. An azoospermic man with a de novo point mutation in the Y-chromosomal gene USP9Y. . Nat Genet. 1999;23:429–32. doi: 10.1038/70539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonova O, Fellmann F, Clavequin MC, Roux C, Bresson JL. AZFa deletions in Sertoli cell-only syndrome: a retrospective study. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:795–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.9.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, Tajima A, Shichiri K, Tanaka A, Tanaka K, et al. Genome-wide expression of azoospermia testes demonstrates a specific profile and implicates ART3 in genetic susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie S, Tsujimura A, Miyagawa Y, Ueda T, Matsuoka Y, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the PRDM9 (MEISETZ) gene in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia. J Androl. 2009;30:426–31. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Jeon S, Choi M, Lee MH, Park M, et al. Mutations in SOHLH1 gene associate with nonobstructive azoospermia. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:788–93. doi: 10.1002/humu.21264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong JT, Zhang SZ, Ma YX, Yang KX, Huang MK, et al. Screening for ZNF230 gene mutation and analysis of its correlation with azoospermia. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2005;22:258–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun YJ, Park JH, Song SH, Lee S. The association of 4a4b polymorphism of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene with the sperm morphology in Korean infertile men. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buldreghini E, Mahfouz RZ, Vignini A, Mazzanti L, Ricciardo-Lamonica G, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene (Glu298Asp variant) in infertile men with asthenozoospermia. J Androl. 2010;31:482–8. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.008979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccarello D, Ferlin A, Cazzadore C, Pepe A, Garolla A, et al. Mutations in dynein genes in patients affected by isolated non-syndromic asthenozoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1957–62. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccetti B, Collodel G, Gambera L, Moretti E, Serafini F, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and molecular studies in infertile men with dysplasia of the fibrous sheath. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunel-Ozcan A, Basar MM, Kisa U, Ankarali HC. Hereditary haemochromatosis gene (HFE) H63D mutation shows an association with abnormal sperm motility. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:1709–14. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zariwala MA, Mahadevan MM, Caballero-Campo P, Shen X, et al. A heterozygous mutation disrupting the SPAG16 gene results in biochemical instability of central apparatus components of the human sperm axoneme. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:864–71. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.063206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaros LA, Xita NV, Chatzikyriakidou AL, Kaponis AI, Grigoriadis NG, et al. Association of TNFalpha, TNFR1 and TNFR2 polymorphisms with sperm concentration and motility J Androle-pub ahead of print 24 February doi:10.2164/jandrol.110.011486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Turner RM, Foster JA, Gerton GL, Moss SB, Patrizio P. Molecular evaluation of two major human sperm fibrous sheath proteins, pro-hAKAP82 and hAKAP82, in stump tail sperm. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:267–74. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM, Musse MP, Mandal A, Klotz K, Jayes FC, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of two human sperm fibrous sheath proteins, AKAP4 and AKAP3, in men with dysplasia of the fibrous sheath. J Androl. 2001;22:302–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon VS, Shahid M, Husain SA. Associations of MTHFR DNMT3b 4977 bp deletion in mtDNA and GSTM1 deletion, and aberrant CpG island hypermethylation of GSTM1 in non-obstructive infertility in Indian men. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:213–22. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. The role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) T-786C, G894T, and 4a/b gene polymorphisms in the risk of idiopathic male infertility. Mol Reprod Dev. 2010;77:720–7. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu A, Ji G, Shi X, Long Y, Xia Y, et al. Genetic variants in Piwi-interacting RNA pathway genes confer susceptibility to spermatogenic failure in a Chinese population. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2955–61. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen GL, Ivanov IP, Wooding SP, Atkins JF, Mielnik A, et al. Identification of polymorphisms and balancing selection in the male infertility candidate gene, ornithine decarboxylase antizyme 3. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai YC, Wang WC, Yang JJ, Li SY. Expansion of CAG repeats in the spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) gene in idiopathic oligozoospermia patients. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:257–61. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9325-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuti F, Krausz C. Gene polymorphisms/mutations relevant to abnormal spermatogenesis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16:504–13. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk M, Jaklič H, Zorn B, Peterlin B. Association between male infertility and genetic variability at the PON1/2 and GSTM1/T1 gene loci. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economopoulos KP, Sergentanis TN, Choussein S. Glutathione-S-transferase gene polymorphisms (GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1) and idiopathic male infertility: novel perspectives versus facts. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:557–8. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirumala Vani G, Mukesh N, Siva Prasad B, Rama Devi P, Hema Prasad M, et al. Role of glutathione S-transferase Mu-1 (GSTM1) polymorphism in oligospermic infertile males. Andrologia. 2010;42:213–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. The association of glutathione-S-transferase gene polymorphisms (GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1) with idiopathic male infertility. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:565–70. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finotti AC, Costa E, Silva RC, Bordin BM, Silva CT, et al. Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphism in men with idiopathic infertility. Genet Mol Res. 2009;8:1093–8. doi: 10.4238/vol8-3gmr642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paracchini V, Garte S, Taioli E. MTHFR C677T polymorphism, GSTM1 deletion and male infertility: a possible suggestion of a gene–gene interaction. Biomarkers. 2006;11:53–60. doi: 10.1080/13547500500442050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydos SE, Taspinar M, Sunguroglu A, Aydos K. Association of CYP1A1 and glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms with male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:541–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vani GT, Mukesh N, Siva Prasad B, Rama Devi P, Hema Prasad M, et al. Association of CYP1A1*2A polymorphism with male infertility in Indian population. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;410:43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, Wu B, Xia Y, Wang W, Gu A, et al. Polymorphisms in CYP1A1 gene are associated with male infertility in a Chinese population. Int J Androl. 2008;31:527–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche E, Schuppe HC, Döhr O, Ruzicka T, Gleichmann E, et al. Increased frequencies of cytochrome P4501A1 polymorphisms in infertile men. Andrologia. 1998;30:125–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1998.tb01387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatsenko AN, Roy A, Chen R, Ma L, Murthy LJ, et al. Non-invasive genetic diagnosis of male infertility using spermatozoal RNA: KLHL10 mutations in oligozoospermic patients impair homodimerization. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3411–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SY, Zhang CJ, Peng HY, Yao YF, Shi L, et al. CAG-repeat variant in the polymerase gamma gene and male infertility in the Chinese population: a meta-analysis. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:298–304. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinka T, Sato Y, Chen G, Naroda T, Kinoshita K, et al. Molecular characterization of heat shock-like factor encoded on the human Y chromosome, and implications for male infertility. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:297–306. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinci G, Raicu F, Popa L, Popa O, Cocos R, et al. A deletion of a novel heat shock gene on the Y chromosome associated with azoospermia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:295–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachini C, Nuti F, Turner DJ, Laface I, Xue Y, et al. TSPY1 copy number variation influences spermatogenesis and shows differences among Y lineages. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4016–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz C, Chianese C, Giachini C, Guarducci E, Laface I, et al. The Y chromosome-linked copy number variations and male fertility. J Endocrinol Invest. 2011;34:376–82. doi: 10.1007/BF03347463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunnotel O, Hiripi L, Lagan K, McDai JR, de León JM, et al. Allterations in the steroid hormone receptor co-chaperone FKBPL are associated with male infertility: a case–control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal F, Item CB, Ratschmann R, Ali M, Plas E, et al. Molecular analysis of guanidinoacetate-N-methyltransferase (GAMT) and creatine transporter (SLC6A8) gene by using denaturing high pressure liquid chromatography (DHPLC) as a possible source of human male infertility. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2011;24:75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Matsuoka Y, Onishi M, Kitamura K, Miyagawa Y, et al. Expression profiles and single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis of human HANP1/H1T2 encoding a histone H1-like protein. Int J Androl. 2006;29:353–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Park HS, Kim HH, Yun YJ, Lee DR, et al. Functional polymorphism in H2BFWT-5'UTR is associated with susceptibility to male infertility. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1942–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlin B, Kunej T, Hruskovicová H, Ferk P, Gersak K, et al. Analysis of the hemochromatosis mutations C282Y and H63D in infertile men. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1796–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassun Filho PA, Cedenho AP, Lima SB, Ortiz V, Srougi M. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the heat shock protein 90 gene in varicocele-associated infertility. Int Braz J Urol. 2005;31:236–42. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382005000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montjean D, Benkhalifa M, Dessolle L, Cohen-Bacrie P, Belloc S, et al. Polymorphisms in MTHFR and MTRR genes associated with blood plasma homocysteine concentration and sperm counts. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:635–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusz KM, Tomczyk L, Sajek M, Spik A, Latos-Bielenska A, et al. The highly conserved NANOS2 protein: testis-specific expression and significance for the human male reproduction. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15:165–71. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusz K, Tomczyk L, Spik A, Latos-Bielenska A, Jedrzejczak P, et al. NANOS3 gene mutations in men with isolated sterility phenotype. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:804. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashamboo A, Ferraz-de-Souza B, Lourenço D, Lin L, Sebire NJ, et al. Human male infertility associated with mutations in NR5A1 encoding steroidogenic factor 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan JJ, Buch B, Cruz N, Segura A, Moron FJ, et al. Multilocus analyses of estrogen-related genes reveal involvement of the ESR1 gene in male infertility and the polygenic nature of the pathology. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:910–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusz K, Ginter-Matuszewska B, Ziolkowska K, Spik A, Bierla J, et al. Polymorphisms of the human PUMILIO2 gene and male sterility. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74:795–9. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerveld GH, Korver CM, van Pelt AM, Leschot NJ, van der Veen F, et al. Mutations in the testis-specific NALP14 gene in men suffering from spermatogenic failure. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3178–4. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Su D, Yang Y, Zhang W, Liu Y, et al. Some single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the TSSK2 gene may be associated with human spermatogenesis impairment. J Androl. 2010;31:388–92. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.008466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su D, Zhang W, Yang Y, Zhang H, Liu YQ, et al. c.822+126T>G/C: a novel triallelic polymorphism of the TSSK6 gene associated with spermatogenic impairment in a Chinese population. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:234–9. doi: 10.1038/aja.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohozinski J, Lamb DJ, Bishop CE. UTP14c is a recently acquired retrogene associated with spermatogenesis and fertility in man. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:644–51. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.046698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B, Xu Z, Ruan J, Zhu M, Jin K, et al. MTHFR 677C>T and 1298A>C polymorphisms and male infertility risk: a meta-analysis Mol Biol Rep 2011. e-pub ahead of print 4 June doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0946-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wu W, Shen O, Qin Y, Lu J, Niu X, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and the risk of male infertility: a meta-analysis Int J Androle-pub ahead of print 28 April doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davis-Dao CA, Tuazon ED, Sokol RZ, Cortessis VK. Male infertility and variation in CAG repeat length in the androgen receptor gene: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4319–26. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz C, Sassone-Corsi P. Genetic control of spermiogenesis: insights from the CREM gene and implications for human infertility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10:64–71. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60805-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Lu N, Xia Y, Gu A, Wu B, et al. FAS and FASLG polymorphisms and susceptibility to idiopathic azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18:141–7. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G, Gu A, Hu F, Wang S, Liang J, et al. Polymorphisms in cell death pathway genes are associated with altered sperm apoptosis and poor semen quality. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2439–46. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Zhang S, Xiao C, Yang Y, Zhoucun A. Mutation screening of the FKBP6 gene and its association study with spermatogenic impairment in idiopathic infertile men. Reproduction. 2007;133:511–6. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamato T, Sato H, Yogev L, Kleiman S, Namiki M, et al. Is a genetic defect in Fkbp6 a common cause of azoospermia in humans. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2006;11:557–69. doi: 10.2478/s11658-006-0043-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerveld GH, Repping S, Lombardi MP, van der Veen F. Mutations in the chromosome pairing gene FKBP6 are not a common cause of non-obstructive azoospermia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:673–5. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giwercman YL, Nikoshkov A, Byström B, Pousette A, Arver S, et al. A novel mutation (N233K) in the transactivating domain and the N756S mutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor gene are associated with male infertility. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;54:827–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giwercman A, Kledal T, Schwartz M, Giwercman YL, Leffers H, et al. Preserved male fertility despite decreased androgen sensitivity caused by a mutation in the ligand-binding domain of the androgen receptor gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2253–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.6.6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Zhang W, Su D, Yang Y, Ma Y, et al. Some single nucleotide polymorphisms of MSY2 gene might contribute to susceptibility to spermatogenic impairment in idiopathic infertile men. Urology. 2008;71:878–82. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud S, Emery BR, Dunn D, Weiss RB, Carrell DT. Sequence alterations in the YBX2 gene are associated with male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1090–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi P, Rossi P, Dolci S, Ripamonti CB, Geremia R. Molecular genetics of male infertility: stem cell factor/c-kit system. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2002;48:27–33. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2002.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan JJ, de Felici M, Buch B, Rivero MC, Segura A, et al. Association of genetic markers within the KIT and KITLG genes with human male infertility. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3185–92. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud S, Emery BR, Dunn D, Weiss RB, Carrell DT. Sequence alterations in the YBX2 gene are associated with male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1090–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Zhang W, Su D, Yang Y, Ma Y, et al. Some single nucleotide polymorphisms of MSY2 gene might contribute to susceptibility to spermatogenic impairment in idiopathic infertile men. Urology. 2008;71:878–2. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler-Smith C, Krausz C. The will-of-the-wisp of genetics—hunting for the azoospermia factor gene. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:925–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0900301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]