Abstract

This study tests for the efficacy of a school-based drug prevention curriculum (Think Smart) that was designed to reduce use of Harmful Legal Products (HLPs, such as inhalants and over-the-counter drugs), alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs among fifth- and sixth-grade students in frontier Alaska. The curriculum consisted of 12 core sessions and 3 booster sessions administered 2 to 3 months later, and was an adaptation of the Schinke life skills training curriculum for Native Americans. Fourteen communities, which represented a mixture of Caucasian and Alaska Native populations in various regions of the state, were randomly assigned to intervention or control conditions. Single items measuring 30-day substance use and multi-item scales measuring the mediators under study were taken from prior studies. Scales for the mediators demonstrated satisfactory construct validity and internal reliability. A pre-intervention survey was administered in classrooms in each school in the fall semester of the fifth and sixth grades prior to implementing the Think Smart curriculum, and again in the spring semester immediately following the booster session. A follow-up survey was administered 6 months later in the fall semester of the sixth and seventh grades. A multi-level analysis found that the Think Smart curriculum produced a decrease (medium size effect) in the proportion of students who used HLPs over a 30-day period at the 6 month follow-up assessment. There were no effects on other drug use. Further, the direct effect of HLPs use was not mediated by the measured risk and protective factors that have been promoted in the prevention field. Alternative explanations and implications of these results are discussed.

Keywords: Youths' harmful legal product use, School-based prevention, Randomized trial, Alaska

Introduction

Harmful legal products (HLPs) consumed by children and adolescents for euphoric effects are not comprised of any single predominant substance or group of substances, but instead consist of many different types of substances found in many different products that are readily available to children and adolescents. One type of HLP is inhalants, most of which are volatile solvents (liquids that can dissolve a number of other substances) (Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission 2004). Examples of volatile solvents are paint thinners, gasoline, and model airplane glue. Other types of inhalants include a variety of aerosols, nitrites (or “poppers”), and anesthetics (Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission 2004; Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 2003; Wu et al. 2005). HLPs are distinct from other substances that may be abused by adolescents because they are legal to purchase or possess.

Among all the different kinds of euphoria-inducing HLP use in which young people may engage, inhalant use has received the most attention (Johnston et al. 2005; Volkow 2005). While the use of illegal drugs continued a gradual decline in 2006, the prevalence of inhalant use in the U.S. showed an upward turn from the prior year (Johnston et al. 2006). The lifetime prevalence rate for inhalant use among eighth graders exceeded the prevalence rate for marijuana, making inhalants the third most commonly used substance, behind alcohol and cigarettes, for this age group (Johnston et al. 2005).

It has also been documented that ingesting prescription drugs (McCabe et al. 2004; McCabe and Boyd 2005), non-prescription, or over-the-counter, drugs (Crouch et al. 2004), and common household products like aftershave (Egbert et al. 1986) and Lysol (Vinje and Hewitt 1992) constitute problems among youth. The recent Partnership for a Drug-Free America Partnership Attitude Tracking Study (PATS) from 2005 showed that nearly one in five teens (19%) reported abusing prescription medications to get high, and one in ten (10%) reported abusing cough medicine to get high (Partnership for a Drug-Free America 2005). Another recent study in four Alaskan communities with populations ranging from about 3,500–9,000 established the lifetime prevalence of HLP use among 10- to 12-year-old youth at 17.4% (Saylor et al. 2007).

Research shows that inhalant-using youth are more likely to use other substances and to start using them earlier (Smitham et al. 1999). Schultz et al. (1994) found that, after controlling for demographics and marijuana use, youth who had used inhalants were at least five times as likely to report injection drug use as those with no history of inhalant use. Similar findings have been reported for later use of injectible drugs (Dinwiddie et al. 1991), heroin (Johnson et al. 1995) and other psychoactive drugs (Bennett et al. 2000; Storr et al. 2005). Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2005) showed that among youth aged 12 to 13 who reported lifetime inhalant use, 35% had used an illicit drug, compared with only 8% of youth in this age group who had never used inhalants. Young et al. (1999) noted that substance use tends to follow a predictable progression where alcohol and cigarette use is followed by marijuana, then cocaine, hallucinogens, and opiates. Contrary to this trend, their study of adolescents incarcerated in a juvenile detention facility showed that for those with an inhalant abuse history, inhalants were the first substance of abuse, preceding even cigarettes by 1.5 years.

Studies of negative consequences of using various HLPs are limited; however, there has been some research that focuses specifically on inhalant-use-related consequences. Inhalant use has been linked to negative consequences that include low academic performance (Bates et al. 1997), delinquency (Mackesy-Amiti and Fendrich 1999), elevated rates of childhood aggressiveness, and alcohol dependency (Howard et al. 1999). Howard and Jenson (1999) noted that inhalant use was a marker for suicidal and criminal behaviors and family problems. A number of authors (e.g., Brouette and Anton 2001) have shown that inhalant abuse often leads to serious health consequences, including neuro-psychological impairment and abnormalities (Chadwick and Anderson 1989), schizophreniform illnesses, and long-term hospital care (Byrne et al. 1991). Death due to either inhalable products or other methods of inhalant abuse has also been highlighted in the literature (Bowen et al. 1999; Maxwell 2001; Spiller 2004). A recent analysis of inhalant abuse cases reported between 1996 and 2001 to U.S. Poison Centers (Spiller 2004) showed 20% (2,330 out of 11,670) had a serious outcome such as attempted suicide, and 0.5% (63 cases) resulted in death. The author also noted that the number of deaths identified in his study (63 deaths associated with cases of intentional inhalation abuse reported to U.S. Poison Centers during this period) was likely just a small portion of the total deaths in the U.S. due to inhalant abuse (Spiller 2004). Balster (2005) noted that inhalant use may contribute to medical conditions that enhance the likelihood of mortality; but, inhalants themselves might not appear as the cause of death.

A School Prevention Education Approach to Reducing HLP Use

In an effort to address the problem of pre- and early adolescents' use of HLPs in frontier Alaska, we tested for the effects of a substance abuse prevention school curriculum, Think Smart, which was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) over 3 years (2004–2007). Think Smart is an adaptation of Steven Schinke and colleagues' (2000) substance abuse prevention curriculum for Native American adolescents. The conceptual framework of the Schinke curriculum drew primarily from Botvin's cognitive–behavioral model that emphasizes teaching drug refusal skills, anti-drug norms, personal self-management skills, and general social skills in an effort to resist drug offers, decrease the motivations to use drugs, and decrease vulnerability to drug use social influences (Botvin et al. 2001; Griffin et al. 2003). The Schinke curriculum also focuses on: knowledge of drugs and the consequences of drug use taken from an informational education approach, attitudes toward drug use that come from cognitive–affective approaches (Petraitis et al. 1995), and bicultural competence that is highlighted in acculturation theory (Gilchrist et al. 1987; Schinke et al. 1988).

The conceptual framework of the Think Smart curriculum includes most of the variables in the Schinke model, although some measures of particular variables come from other sources, as shown later in the measures subsection. We used multiple measures of 30-day alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drug use, but expanded the number of harmful legal products to include use of inhalants, prescription and over-the-counter drugs, and household products.

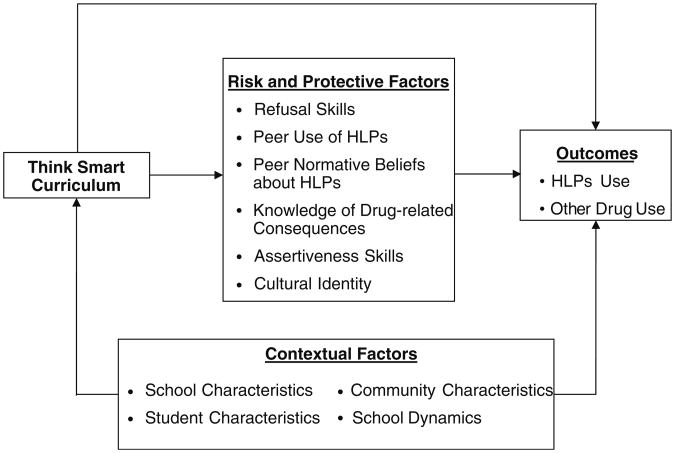

Six mediators (three risk and three protective factors of the Think Smart model) were as follows. We included refusal skills as a risk factor, because such skills are posited to help adolescents resist peer and other pressure. Peer use of harmful legal products and peer normative beliefs about HLPs are also targeted risk factors, reflecting the importance of combining a focus on norm setting with skills or competency enhancement. Knowledge about drugs and the consequences of drug use is a protective factor that serves as a precursor to behavioral change. Assertiveness skills also constitute a protective factor that is based on the assumption that general social skills are important to prevention. A third protective factor is cultural identity relating to living in Alaska, although Schinke focused on bicultural competence skills. This measurement adaptation stems from the reality, contrary to common belief, that many frontier communities are comprised of mixed populations with the majority being Caucasian, and Alaska Natives being in the minority. Thus, we posit that the lack of identity with the values, beliefs, and norms of the Alaskan culture might be linked to increased use of HLPs and other drugs.

Figure 1 presents a conceptual view of the Think Smart conceptual framework and its assumed causal relationships between the curriculum, risk and protective mediators, and HLPs and other drug use. This conceptualization is considered the intervention theory of the study. It is posited that the Think Smart prevention curriculum will positively affect the use of HLPs and other drugs, largely through a set of risk and protective factors that have been key to the life skills conceptual model. The identified categories of contextual factors may create spurious effects and therefore need to be controlled in the analysis. The specific contextual factors are described in the measures subsection of the paper.

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework of the adapted Schinke school-based prevention program effects on inhalant and other drug use in rural Alaska.

The specific research questions being examined are:

What are the direct effects of Think Smart on youths' use of HLPs and other drugs?

What are the direct effects of Think Smart on the risk and protective factors that are assumed to mediate the use of HLPs and other drugs?

To what extent do these risk and protective factors mediate Think Smart's effects on youths' use of HLPs and other drugs?

Methods

Study Population

The study involved students from the school systems of 14 communities in Alaska. The communities can be described as frontier, or isolated, rural communities. The National Center for Frontier Communities (NCFC) defines frontiers not only by population density, but also by the distance and time between communities within a county to a service/market center (National Center for Frontier Communities 2007b). The communities that participated in the HLPs study represent part of the 52% of Alaska's population that is identified as frontier (National Center for Frontier Communities 2007a). All but two of the communities are located off the road system (i.e., air- and water-craft are the only means of access), and residents rely on air, ferry, and ship service from Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Seattle not only for personal transportation, but also for mail, groceries, and all other commodities. The communities range in size from approximately 400 to 5,000. Eight communities have predominately Alaska Native populations, including six villages with Alaska Native populations greater than 90%. Four communities have a majority White population; the other two are heavily diverse with no majority group. Ten school districts serve the participating 14 communities. One school district involved its schools in two communities, and one involved its schools in four communities.

Think Smart Curriculum

The Think Smart curriculum is a modified form of the Personal Intervention Curriculum, which is based on an abstinence-based prevention model developed by Stephen Schinke for a Pacific Northwest American Indian population (Ogilvie et al. 2006; Schinke et al. 1988, 2000). Schinke's original curriculum, which drew heavily from Botvin's Life Skills Training, required modification for a number of reasons. First, the original curriculum material, which is marketed by Sociometrics, Inc., needed to be updated for content (e.g., more emphasis on harmful legal products); substitution of Alaskan culture material instead of Northwest American Indian culture; and practicality (e.g., creation of an electronic version for printing as well as the development of a teaching kit). Second, in order to be integrated into classroom settings, the lessons were standardized into 45- to 60-min sessions, as opposed to the variety of session lengths that Schinke had developed for a more flexible school environment.

Study team members involved in the adaptation included scientists from the research team, Sociometrics (the firm that holds the rights to Schinke's curriculum), as well as Alaska Native and other Alaskan consultants. The curriculum was not adapted for Alaska Natives specifically, but for frontier Alaska more generally. This generalization sought to capture the common experience of frontier Alaskan youth regardless of their heritage. This experience is juxtaposed to American Indian experiences on reservations (the Schinke curriculum).

In making the adaptations, the study team utilized Ringwalt and Bliss's (2006) synthesis of three types of adaptations: surface, deep, and evidential. That is, to make it more relevant to frontier Alaska, surface adaptations included Alaska-specific visuals and examples, deep adaptations involved integrating the values of Alaskan people (e.g., not including “BINGO,” which was used in Schinke's curriculum, because gambling is a serious problem in frontier Alaskan communities), and evidential adaptations provided more Alaskan-specific statistics. Lessons learned in a prior NIDA-funded feasibility study that included an earlier version of Think Smart fed into a revised curriculum that was implemented in this study (Johnson et al. 2007).

The Think Smart curriculum consists of 12 core sessions, including introductory and concluding sessions, and three booster sessions implemented 2 to 3 months later. The core sessions include sessions on stereotypes and drug facts and then the introduction of a problem-solving model known as S.O.D.A.S. (Stop, Options, Decide, Act, Self-Talk), which emphasizes refusal and self-assertiveness skills. The stereotypes session addresses the concept of peer norms and cultural identify. The final core sessions and the booster sessions involve practicing this problem-solving model. The curriculum involves many interactive activities, including role plays and other engaging methods.

In this study, the core and booster sessions were taught weekly as one-hour sessions in fifth- and sixth-grade classrooms by the classroom teachers. The core sessions were taught between October 2006 and February 2007 in the seven intervention communities. The booster sessions were implemented 2 to 3 months later during March through May 2007. The teachers received a 2-day, on-site training from the intervention agency partner. This agency partner and a trained, local Prevention Project Coordinator (PPC) offered technical assistance to the teachers throughout the curriculum's implementation. A complete teaching kit that included all of the materials necessary to implement the interactive curriculum (e.g., laminated role play cards, timers etc.) was given to each teacher. Teachers were also given video cameras to record all of the sessions in order to facilitate a study of the implementation fidelity and quality (Johnson et al., in review).

Research Design

A two-group, randomized, matched-control trial with nested repeated measures of youth (fifth and sixth grades) was employed to answer the three research questions concerning the Think Smart effects on youths' use of HLPs to get high. This design, which models a subgroup of participants with repeated measures, is a powerful and efficient alternative to cross-sectional designs when practical requirements can be met.

Early in the pre-intervention phase of the study, 16 communities were matched on three variables: (1) number of K-12 students enrolled in regular public school in the community; (2) percentage of the population that was non-White in the 2000 U.S. Census; and (3) region of Alaska. Following the matching, a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was generated using its automatic function “RAND” to finalize the assignment of the communities in the experimental and control conditions. One control group community dropped out of the study; therefore, we also dropped the matched intervention community, reducing the number of communities available for the outcome assessment to 14 communities. Although, in aggregate, the two groups are similar, as shown later in Table 1, there is considerable community diversity within each group (e.g., variation in community size, proportion of Alaska Natives, proximity to the larger communities that are the origin of supplies and services). This diversity is desirable, as it supports generalizations of study results to comparably diverse communities in Alaska and other frontier areas in the U.S. and worldwide. Cross-contamination between intervention and control sites is unlikely because the distance between communities averages 250 miles and most are accessible only by air.

Table 1. Parental consent returns, and parental refusals/positive consent by year and group for 14 communities.

| 2006 | 2007 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Intervention | Control | Total | Intervention | Control | Total | |

| Student enrollment | 317 | 289 | 606 | 313 | 297 | 610 |

| Consent forms returned | ||||||

| Number | 288 | 274 | 562 | 280 | 271 | 551 |

| Percentage | 91 | 95 | 93 | 89 | 91 | 90 |

| Parental refusals | ||||||

| Number | 37 | 29 | 66 | 40 | 49 | 89 |

| Positive consent | ||||||

| Number | 251 | 245 | 496 | 240 | 222 | 462 |

| Percentage | 79 | 85 | 82 | 77 | 75 | 76 |

The design calls for student data (Baseline—Wave 1) to be collected prior to Think Smart implementation in each school early in the fall semester, and again late in the spring semester immediately following the booster sessions (Post-intervention—Wave 2). A 6-month follow-up survey (Wave 3) was administered in the fall of the next academic year to the same cohort of students.

Measures

Substance Use Outcomes These outcomes are past 30-day use of: (1) Harmful legal products (HLPs) constructed as a use/nonuse composite consisting of four types of HLPs (a) inhalants (used for the purpose of getting high), (b) prescription medicines (used without a doctor's orders), (c) over-the-counter medications, and (d) common household products (used for the purpose of getting high). Thirty-day use of other substances include (2) tobacco [cigarettes and smokeless], (3) alcohol, and (4) marijuana or hashish. An example of the survey questions is “On how many occasions (times), if any, have you sniffed glue, breathed the contents of an aerosol spray can or inhaled other gases or sprays in order to get high in the past 30 days? [0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–39, 40 or more].” For each of these outcomes, we recoded responses so that no use was “0” and all other responses were “1.” An exploratory analysis showed the data were heavily left censored across all 30-day substance abuse measures with relatively low levels of use. Further, we found variability would not be increased substantially by examining measures as continuous, as opposed to dichotomous.

The measures for use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, inhalants, prescription medicines, and over-the-counter medications were taken from Arthur et al. (1998), and the measure for use of common household products for the purpose of getting high was developed for this study.

Mediating Variables Five scales consisting of five risk and protective factors were constructed to measure the mediators in this study. Unfortunately, we were unable to construct an acceptable valid and reliable scale measuring youths' refusal skills. The two risk factors we measured are assumed to be positively correlated with HLPs use: (1) Peer Use of HLPs (four items, for example: “In the past year, how many of your best friends have sniffed or huffed gasoline, glue or other solvents to get high?”); and (2) Peer Normative Beliefs about HLPs (four items, for example: “Would your best friends say it is cool to use over-the-counter medicines like cough syrup or stay-awake pills to get high?”). Responses on Peer Use of HLPs were from 0 to 4 friends (who used), and responses on Peer Normative Beliefs about HLPs were from 0 (definitely false) to 3 (definitely true)—(α=0.84 and 0.91 respectively).

The three protective factors assumed to be negatively or inversely correlated with HLP use are: (1) Knowledge of Drugs and Consequences of Use (seven items, for example: “Smoking cigarettes can hurt your lungs, but not your heart”); (2) Assertiveness Skills (nine items, for example: “How likely would it be that you tell people your opinion, even if you know they will not agree with you?”); (3) Cultural Identity (six items, for example: “I have a strong sense of belonging to my Alaskan community”). For Knowledge of Drugs and Consequences of Use, we coded correct responses as 1, and incorrect responses as 0. To reduce guessing, a “don't know” response was also coded as 0. Assertiveness Skills item responses ranged from 0 (definitely would not use skill) to 4 (definitely would use skill). Responses on Cultural Identity ranged from 0 (definitely false) to 3 (definitely true). Alpha reliabilities for these three scales were 0.67, 0.75, 0.82, respectively.

All measures for the mediators have been used elsewhere. The items measuring Knowledge of Drugs and Consequences of Use and items measuring Cultural Identity were modified from items in Gilchrist et al. (1987). Items for Assertiveness Skills were modified from items in Scheier et al. (1999). Items for Peer Use of HLPs and Peer Normative Beliefs were modified from items in Hansen and McNeal (1997). With the exception of the knowledge scale, construct validity was re-validated for each scale via factor analysis. Factor loadings for each of these four scales exceeded 0.60. The final scale for each mediator (except the Knowledge scale) was computed as the mean of constituent survey items after first using the Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm to impute missing values on items making up each scale. (For details about this imputation procedure, see the analysis subsection below). For Knowledge of Drugs and Consequences of Use, we computed a count of the number of correct responses across the seven constituent items.

Student Characteristics Individual survey items measured: (1) age, (2) grade in school, (3) gender, (4) ethnicity, (5) household composition (one item measuring the number of siblings who live with the student), (6) mother's job status, (7) father's job status, and (8) free- or reduced-price lunch eligibility.

Community/School-Level Characteristics These measures included the following: (1) community population (2006), (2) percentage of White population in the community, (3) poverty rate, (4) average experience level of teachers, (5) number of vandalism incidents, (6) number of enrolled students, (7) number of suspensions and expulsions (across nine possible types), (8) number of school incidents (across nine possible types), (9) rate of in-migration, (10) rate of out-migration, (11) proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, and (12) school system readiness to implement substance abuse prevention programs. School readiness to implement substance abuse prevention programs was measured using a telephone survey of key informants (on average seven per community) from 14 communities (total n=100). The school readiness survey was based on constructs from the Community Readiness Model developed by the Tri-Ethnic Center at the University of Colorado (Oetting et al. 1995). Items are included in the survey that measure six dimensions of school readiness to deal with the issue of harmful legal products: efforts, knowledge of efforts, leadership, climate, knowledge about the issue, and resources. The data were aggregated to the community level (n=14). At the community level, the alpha reliabilities for the six dimensions of readiness, each of which consisted of three to six items, ranged from 0.60 to 0.76, and the reliability for the overall community readiness scale was 0.84. The aggregated data on school readiness were merged with the student data file.

School Dynamics Computed school dynamics variables are included for the presence in the school for both evidence-based and non-evidence-based prevention programming. The latter are based on school prevention program inventories implemented in each school during the evaluation period. Evidence-based prevention programs are those that are listed as model or effective on NREPP, model or promising on Blueprints, or exemplary on Department of Education list of programs. Schools in four of the seven intervention communities and four of seven control communities reported having implemented an evidenced-based substance abuse prevention program. To reduce selection biases due to having only seven pairs of communities in the study, we entered the school dynamic variables along with student and community/school characteristics to create a single composite covariate (an Inverse Mills Ratio representing probability of assignment to groups). This procedure is described later in the analysis section of the paper.

Sample and Data

The student survey was administered in a classroom setting for the 14 communities whose data were used in the outcome study. A prevention project coordinator (PPC), who was a representative of the school district, was trained on survey administration protocols. In most cases, the PPC was the principal or counselor of the school, and he or she administered the survey. In four cases, teachers (4 of 40 teachers) were asked to administer the survey in small remote villages where the PPC was not on-site. PPCs and teachers were trained in survey administration procedures, including how to create an atmosphere of confidentiality. A script was read aloud indicating to students that their answers would be kept confidential, and they were asked to seal their surveys in an envelope that was sent directly to the researchers in Anchorage.

The Wave 1 (baseline) data collection occurred in the fall of 2006. The Think Smart curriculum was then delivered to the students over the course of the fall semester and into the month of January in the seven experimental communities. Approximately 2 to 3 months after the end of the core sessions of the curriculum, three booster sessions were taught (April and May 2007). The Wave 2 survey was administered in all 14 communities immediately following the completion of the booster sessions in May of 2007. The Wave 3 follow-up survey was administered 6 to 7 months following the post survey in fall of 2007.

Alaska State Statute 14.03.110 requires written active parental consent for any survey or questionnaire that is administered in the public schools, regardless of whether the questionnaire or survey is anonymous. This law, which passed in 1999, requires a minimum of two weeks notice to parents prior to survey administration, and limits consent to one school year. In the case of this study, this meant we had to obtain parental consent twice, once for the baseline and post surveys and once for the follow-up survey.

All students enrolled in regular public school in the fifth and sixth grades in school year 2006–2007, and in the sixth and seventh grades in school year 2007–2008, were asked to be included in the survey. In one community, the sixth-graders were excluded because the district did not want to involve both grades. Table 1 shows the percentage of parents who returned their forms for the 2006 and 2007 administration for the 14 communities, with an average return rate of 90% and 89%, respectively. Of the parents who returned consent forms, 11% in the first year and 13% in the second year refused to grant consent. Thus, 496 students of the 606 enrolled in 2006 (88%) and 462 students of the 610 enrolled in 2007 (84%) were eligible for the survey.

Table 2 presents the student participation rates for Waves 1, 2, and 3. After subtracting absences and students who declined to provide their assent, the student response rates were 76% (Wave 1), 66% (Wave 2), and 70% (Wave 3) of the total number of enrolled students. Although not shown in table format, we found the student participation rate according to repeated measures for Wave 1–Wave 2 analyses the rate was 81%. For the Wave 1–Wave 3 analyses, the rate was 71%. These latter rates reflect the samples used in the final analyses.

Table 2. Student participation rates by wave and group for 14 communities.

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Interv | Control | Total | Interv | Control | Total | Interv | Control | Total | |

| Student enrollment | 317 | 289 | 606 | 317 | 289 | 606 | 313 | 297 | 610 |

| Student participation | 238 | 222 | 460 | 198 | 203 | 401 | 216 | 212 | 428 |

| Participation rate (participation/enrollment), % | 75 | 77 | 76 | 62 | 70 | 66 | 69 | 71 | 70 |

Interv intervention

Analysis Strategy

The data analyses performed take into consideration several possible limitations of group randomized trials with repeated measurements. More specifically, we address differential selection, attrition (specifically, panel and differential attrition), missing data imputation in the outcome analyses examining program effects, and exploration of possible mediators of possible intervention outcomes.

Differential Selection These analyses explore the possibility that the a priori pairwise random assignment of communities to intervention and comparison group may be systematically different on a larger set of community characteristics, as well as student characteristics. We chose to use the Heckman two-step procedure that adjusts inferential tests for biases caused by selection (Heckman 1976, 1979). The first step in this procedure involves entering all potential covariates as predictors of intervention assignment using a probit regression model.

Our model includes all covariates (Levels 1 and 2) identified as predictors of outcomes at the p<0.20 level (Mickey and Greenland 1989), which are listed in Table 3. The second step in the procedure involves computing a predicted score using the regression model coefficients and then transforming the predicted score to the Inverse Mill's Ratio (IMR). The IMR is used as a predictor in all inferential analyses and the relationship between the IMR and outcomes that represented the proportion of variance explained in the outcome that is due to non-random assignment. The statistically significant community and individual characteristics that contribute to the IMR variable are presented in Table 3. These results show there are no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups for the community, school, student level variables with two exceptions. There were significantly more Alaska Native youth and fifth graders in the control group in comparison to the intervention. These characteristics were included in the construction of the IMR covariate.

Table 3. Background characteristics of intervention vs. control group by differential selection and attrition analyses.

| Means/percentages | Diff. selection | Diff. attrition (post) | Diff. attrition (follow-up) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Overall | Intervention | Control | t | d | t | d | t | d | |

| Community level | |||||||||

| Population 2006 | 1,672.7 | 1,616.1 | 1,729.3 | −0.12 | 0.07 | – | – | – | – |

| Caucasian population 2006 | 869.6 | 639.1 | 1,100.0 | −0.83 | 0.46 | – | – | – | – |

| % in poverty | 16.8 | 15.7 | 17.9 | −0.43 | 0.23 | – | – | – | – |

| Teacher experience level | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.4 | −0.41 | 0.22 | – | – | – | – |

| % Vandalism | 1.57 | 1.4 | 1.7 | −0.33 | 0.18 | – | – | – | – |

| N students | 200.0 | 192.0 | 208.1 | −0.34 | 0.19 | – | – | – | – |

| % Immigration | 2.1 | 1.1 | 3.1 | −1.11 | 0.63 | – | – | – | – |

| % Migration | −3.8 | −2.4 | −5.2 | 1.07 | −0.60 | – | – | – | – |

| % Free and reduced lunch | 65.5 | 71.1 | 59.8 | 0.71 | −0.39 | – | – | – | – |

| School problems (e.g., expulsions) | 6.2 | 7.3 | 5.1 | 0.45 | −0.25 | – | – | – | – |

| % Evidence-based prevention | 57.1 | 57.1 | 57.1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| % Non-evidence-based prevention | 85.7 | 85.7 | 85.7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Community readiness to prevent HLPs use Student characteristics | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | −0.66 | 0.35 | – | – | – | – |

| % Male | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.87 | 0.16 | 0.69 | −0.06 | 0.99 | −0.10 |

| Grade | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 | −3.30* | −0.29 | 0.91 | −0.08 | −1.69 | 0.17 |

| % AK Native/American Indian | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 5.07* | 0.44 | 0.86 | −0.08 | 1.36 | −0.13 |

| % Caucasian | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | −0.13 | −0.01 | −3.48* | 0.32 | −2.46* | 0.24 |

p<0.05, two-tailed

Attrition Bias Similar t-tests were performed comparing those who stayed in the study to those who dropped out of the study on four individual characteristics that were available for all participants at pre-test (gender, grade, Alaska Native/American Indian, and Caucasian). Data also were available on baseline substance use. These analyses were not performed at the community level, as individuals, and not communities, left the study. These analyses were performed separately for attrition at post-test (ndropper=168 vs. nstayers=401) and attrition at follow-up (ndropper=168 vs. nstayers=401). Table 3 results show that droppers and stayers did not differ on past 30-day substance use at baseline for any of the substances examined (p>0.05), and they did not differ on most of the individual characteristics. The one characteristic on which droppers and stayers differed is that Caucasians were more likely to leave the study at both post-test and follow-up. However, the magnitude of this difference was not impressive at post-test (d=0.32) or follow-up (d=0.24). As a result of these analyses, no further treatment is given to attrition.

Missing Data Imputation Missing covariate and mediator-of-substance-use data were imputed using the Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm. The EM algorithm replaces missing data in a manner such that the observed covariance matrix from the available data is maximally similar to the reproduced covariance matrix from the imputed data. Data were imputed for the mediators, as there was only a small amount of missing data on average (5%, SD=4%). The pattern of results when examining imputed mediators and non-imputed mediators was identical, so we proceeded with analyses using imputed data. Data were also imputed for individual and community level characteristics, as at most, only 2% of the data were missing. These demographic data were used to create our covariate IMR that adjusts for selectivity.

Intra-class Bias Hierarchical Generalized Linear Modeling (HGLM; Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) was used to examine whether the intervention effects on substance use were biased due to variation across communities. The details of the final analysis strategy are discussed in the Results section.

Results

Level of Substance Use Among Youth in Frontier Communities

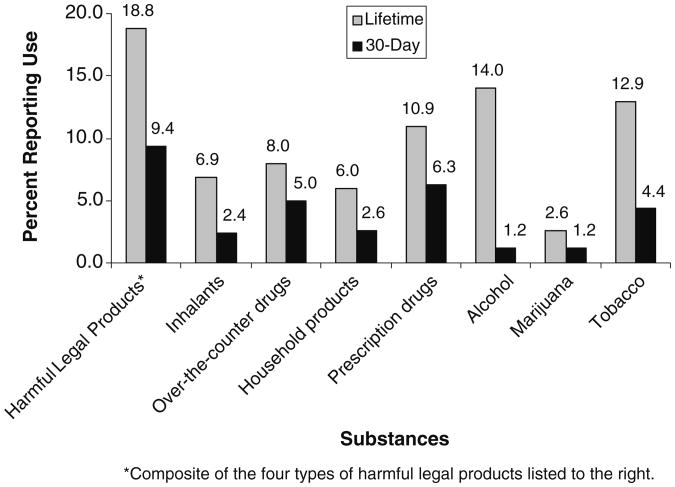

Figure 2 shows the lifetime and 30-day use of HLPs and other substances prior to implementing the Think Smart curriculum. Overall lifetime HLP use among fifth- and sixth-grade students was 18.4% and 30-day use was 9.4%. Prescription drugs have the highest prevalence rate of the four types of HLPs surveyed, followed by over-the-counter-drugs, household products, and inhalants.

Fig. 2. Percentage of lifetime and 30-day use of HLPs and other substances.

Direct Effects

HGLM (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) was used to examine whether the Think Smart prevention curriculum produced direct effects on substance use (Question 1). More specifically, intervention status (a level two variable), the IMR, and baseline standing on each outcome measure (level one variables) were used as predictors of the outcomes at post-test (Wave 2) and 6-month follow-up (Wave 3) in two separate sets of analyses. This analysis strategy for repeated measures data nested in an age cohort design has been recommended by Murray (1998) when assignment occurs at the group level. For these analyses, the intercept was posed as a random effect, which assumes that variability in the outcome varies randomly across communities. The intercept represents a logit transform of the average level of 30 day use across participants when adjusting for random variation across communities and covariates. In addition to model coefficients, effect sizes were calculated for all of the analyses reported using the Odds Ratio (OR) for dichotomous outcomes and transforming the t-statistic to the effect size r using the following formula: r − [t2/(t2+ df)].5 for continuous outcomes (Cohen 1988). A decision was made to analyze these data as dichotomous, as the goal of the Think Smart curriculum is to promote abstinence. Nevertheless, this has the logical consequence that significant intervention effects may be caused by either (a) students using a substance at baseline and abstaining from substance use at a later wave or (b) a large number of students consistently abstaining across time. We discuss this later in the Discussion section.

As can be seen in Table 4, Think Smart had an impact on 30-day HLP use, but it did not have an impact on 30-day alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana use. More specifically, the Think Smart curriculum did not have an immediate impact on HLPs use at post-test, but the curriculum did have a medium effect on HLPs use at follow-up, as comparison students were eight times (or 1/0.13) more likely than intervention students to have used HLPs in the past 30 days. Exploring the individual substances that constitute HLPs, it can also be seen in Table 4 that the HLPs effect at follow-up is largely due to comparison students being ten times more likely than the intervention students to have used inhalants in the past 30 days at follow-up. It should be noted that the levels of use of individual types of HLPs were less than 2% other than inhalant use; therefore, the individual HLP substances may be distorted due to floor effects.

Table 4. HLGM examining intervention effects for substance use.

| Substance | Post-test | Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| B (SE) | OR | B (SE) | OR | |

| Any HLPs use (see four products below) | 0 | |||

| HLPs (ICC T2=0.10; T3=0.00) | ||||

| Intercept | −2.74 (0.77)* | 0.06 | −1.96 (0.78)* | 0.14 |

| Intervention | −0.54 (0.70) | 0.58 | −2.08 (0.89)* | 0.13 |

| Inv. mills ratio | −0.22 (0.54) | 0.81 | −1.20 (0.67) | 0.30 |

| Baseline standing | 1.32 (0.48)* | 3.75 | 1.92 (0.74)* | 6.83 |

| Specific HLPs products | ||||

| Inhalants (ICC T2=0.00; T3=0.00) | ||||

| Intercept | −4.22 (1.51)* | 0.01 | −1.64 (0.78)* | 0.19 |

| Intervention | −1.31 (1.54) | 0.27 | −2.30 (0.89)* | 0.10 |

| Inv. mills ratio | 0.04 (1.05) | 1.04 | −1.38 (0.71) | 0.25 |

| Baseline standing | 3.46 (1.20)* | 31.73 | 2.33 (1.13)* | 10.32 |

| OTC (ICC T2=0.21; T3=0.00) | ||||

| Intercept | −3.27 (1.10)* | 0.04 | −2.34 (1.10)* | 0.10 |

| Intervention | −0.45 (1.01) | 0.64 | −1.72 (1.17) | 0.18 |

| Inv. mills ratio | −0.68 (0.81) | 0.51 | −1.45 (0.98) | 0.23 |

| Baseline standing | 2.56 (0.67)* | 12.93 | 2.18 (1.18) | 8.82 |

| Prescriptions (ICC T2=0.00; T3=0.00) | ||||

| Intercept | −4.27 (1.25)* | 0.01 | −4.79 (1.82)* | 0.01 |

| Intervention | −0.25 (1.11) | 0.78 | −0.45 (1.61) | 0.64 |

| Inv. mills ratio | 0.46 (0.78) | 1.59 | 0.09 (1.16) | 1.10 |

| Baseline standing | 2.08 (0.82)* | 7.99 | 3.23 (1.13)* | 25.21 |

| Household products (ICC T2=0.29; T3=0.00) | ||||

| Intercept | −9.33 (3.03)* | 0.00 | −5.20 (1.90)* | 0.01 |

| Intervention | −25.74 (2.E+05) | 0.00 | −28.43 (4.E+05) | 0.00 |

| Inv. mills ratio | 3.24 (1.79) | 25.60 | 0.24 (1.30) | 1.28 |

| Baseline standing | 3.79 (0.63)* | 44.45 | 4.09 (1.20)* | 59.98 |

| Other substances | ||||

| Alcohol (ICC T2=0.25; T3=0.27) | ||||

| Intercept | −3.83 (1.26)* | 0.02 | −2.66 (1.23)* | 0.07 |

| Intervention | 0.09 (1.17) | 1.09 | −0.95 (1.18) | 0.39 |

| Inv. mills ratio | −0.32 (0.89) | 0.73 | −1.31 (0.94) | 0.27 |

| Baseline standing | 4.78 (1.14)* | 119.21 | 3.57 (0.85)* | 35.45 |

| Tobacco (ICC T2=0.64; T3=0.52) | ||||

| Intercept | −3.01 (1.94) | 0.05 | −2.71 (1.55) | 0.07 |

| Intervention | −2.54 (1.84) | 0.08 | −1.02 (1.39) | 0.36 |

| Inv. mills ratio | −0.52 (1.43) | 0.60 | −0.03 (1.09) | 0.97 |

| Baseline standing | 2.97 (0.65)* | 19.39 | 1.86 (0.54)* | 6.39 |

| Marijuana (ICC T2=0.00; T3=0.21) | ||||

| Intercept | −2.36 (0.80)* | 0.09 | −1.37 (1.00) | 0.25 |

| Intervention | −57.22 (5.E+05) | 0.00 | −29.590 (3.E+06) | 0.00 |

| Inv. mills ratio | −1.22 (0.70) | 0.30 | −1.61 (0.90) | 0.20 |

| Baseline standing | 31.72 (3.E+05) | 6.E+13 | −26.43 (1.E+06) | 0.00 |

| N (range) | 316–440 | 276–339 | ||

OTC over the counter

p=0.05, two-tailed

Mediation Effects

To examine possible mediation of the risk and protective factors that are measured in this study, a necessary condition is that the intervention needs to impact a mediator; and, there should be an association between the mediator and an outcome when intervention status is also included in the model (Judd and Kenny 1981). First, we also used HGLM to answer question 2 regarding Think Smart's direct effect on the risk and protective factors. When regressing each of the five factors onto the intervention group variable and the IMC covariate, we found no statistical differences between the intervention and control groups for peer use of HLPs, normative beliefs about peer use, and cultural identity. We did find a gain in knowledge of HLPs immediately after the curriculum implementation (post test) that was significantly larger in the intervention group than in the control group, but these gains dissipated at the 6-month follow-up, only approaching statistical significance (p<0.20). Assertiveness also approached statistical significance (p>0.20) at the 6-month follow-up with a slightly larger gain in the intervention group than in the control group (Table 5).

Table 5. Think Smart effects on mediators of substance use using HLM at post and follow-up assessments.

| Post-test | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| B (SE) | r | B (SE) | r | |

| Peer use of HLPs (ICC T2=0.00; T3=0.02) | ||||

| Intercept | 0.07 (.07) | 0.05 | 0.25 (0.08)* | 0.17 |

| Intervention | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.14 | −0.11 (0.07) | −0.41 |

| Inv. mills ratio | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.04 | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.08 |

| Baseline standing | 0.31 (0.05)* | 0.31 | 0.11 (0.05)* | 0.13 |

| Peer normative beliefs about HLPs (ICC T2=0.00; T3=0.01) | ||||

| Intercept | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.00 | 0.14 (0.06)* | 0.13 |

| Intervention | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.27 | −0.07 (0.05) | −0.33 |

| Inv. mills ratio | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.05 | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.07 |

| Baseline standing | 0.61 (0.06)* | 0.50 | 0.21 (0.06)* | 0.19 |

| Knowledge of drug-related consequences (ICC T2=0.05; T3=0.14) | ||||

| Intercept | 1.88 (0.45)* | 0.21 | 1.76 (0.67)* | 0.15 |

| Intervention | 0.88 (0.37)* | 0.57 | 0.57 (0.55) | 0.29 |

| Inv. mills ratio | −0.32 (0.30) | −0.06 | 0.10 (0.45) | 0.01 |

| Baseline standing | 0.46 (0.05)* | 0.44 | 0.41 (0.06)* | 0.38 |

| Assertiveness skills (ICC T2=0.09; T3=0.00) | ||||

| Intercept | 1.36 (0.26)* | 0.27 | 1.62 (0.18)* | 0.46 |

| Intervention | 0.10 (0.18) | 0.16 | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.37 |

| Inv. mills ratio | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.02 | −0.01 (0.08) | 0.00 |

| Baseline standing | 0.45 (0.05)* | 0.41 | 0.41 (0.05)* | 0.42 |

| Cultural identity (ICC T2=0.03; T3=0.01) | ||||

| Intercept | 0.73 (0.14)* | 0.26 | 1.35 (0.14)* | 0.49 |

| Intervention | −0.05 (0.08) | −0.17 | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.32 |

| Inv. mills ratio | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.01 | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.03 |

| Baseline standing | 0.69 (0.05)* | 0.62 | 0.50 (0.05)* | 0.52 |

| N | 440 | 339 | ||

p<0.05, two-tailed

In answering question 3 regarding mediation, we regressed all outcomes one at a time onto the two protective factors that seemed to be potentially promising as mediators (p>0.20) (i.e., knowledge and assertiveness). In performing this analysis, we found no statistically significant relationship. This evidence suggests that mediation could not occur without these mediators-outcome relationships. Preliminary path models using LISREL also failed to find any evidence of indirect effects.

In a search of alternative empirical explanations as to why Think Smart reduced HLPs use, but not through the posited mediators, we conducted two sets of moderation analyses that examined the interactions effects of (a) intervention vs. contextual factors in Table 3 and (b) intervention vs. change in the risk and protective factors on substance use outcomes. First, there was no evidence of moderation of HLPs use for any of the contextual factors. Second, we examined changes in the mediators as potential moderators of the relationship between intervention and substance use outcomes. More specifically, we performed analyses identical to our outcome analyses; however, we entered changes in risk and protective factors (difference scores) as predictors, and all orthogonal interactions between intervention and our difference scores. These results tend to also rule out the alternative empirical explanation that results from our moderation analysis.

Discussion and Implications

This study examines the effectiveness of an adapted evidence-based substance abuse prevention curriculum, Think Smart, originally developed and tested among Native American youth in Washington State (Schinke et al. 2000). This curriculum was adapted for fifth- and sixth-grade students in schools in frontier Alaska in two NIDA studies awarded in 2004 and 2005. The adapted Think Smart curriculum increased emphasis on youth use of inhalants and other potentially HLPs including prescription drugs, over-the-counter medicines, and household products. The adaptation also emphasized Alaska cultural considerations. Further adaptation in the delivery included adapting the Schinke curriculum to 12 sessions plus 3 booster sessions 2 to 3 months following delivery of the core curriculum. The core sessions of the adapted curriculum were delivered in the fall and early spring sessions and the booster sessions were delivered late in the spring semester.

The results show that the Think Smart curriculum significantly reduced use of harmful legal products at a 6-month assessment after completing the curriculum (medium-sized effects); inhalant use reduction was most prevalent. However, this curriculum did not directly impact youths' use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana. As mentioned earlier, our positive reductions in the use of HLPs may have been influenced by a high percentage of students who reported abstaining at baseline and follow-up. Although frequency of use was measured, we analyzed the data as dichotomous outcomes (a) as logistic models hold fewer distributional assumptions about dependent measures (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001), (b) it would be problematic to treat the continuous measures of use as normally distributed due to left censoring, and (c) examining the outcome of abstinence is the most consistent with the goals of the Think Smart curriculum.

The risk and protective factors measured in this study did not mediate Think Smart effects on reduced substance use among youth while other studies have found one or more of these mediators to be a bridge between the Botvin life skills curriculum and reduced substance use (Botvin et al. 1985; Botvin et al. 1990a, b). More specifically, Botvin et al. (2001) found in a study of the effects of the LifeSkills Training in a sample of predominantly minority students in New York City schools that the behavioral effects of the intervention on inhalant use were mediated partly by peers' use. This lack of mediation of Think Smart effects on HLPs use among youth in this study suggest there may be alternative explanations.

In terms of empirical support for some alternative explanation, we thought that the risk and protective factors measured in this study might produce a moderating (intervention × moderator interaction) effect instead of a mediation effect. The results of this exploratory analysis found no empirical support to this alternative explanation. Implementation fidelity of a prevention intervention has also been found to explain the lack of intervention effects on the desired outcomes (Mokrue et al. 2005; Skara et al. 2005). In this study, we have a companion fidelity paper that found the Think Smart curriculum was implemented with high fidelity in regard to both content and delivery quality (Johnson et al., in review). These results, which stem from a random sample of videotaped observations, suggest the lack of implementation fidelity of the Think Smart curriculum is not an alternative explanation to why the risk and protective factors of this study did not mediate the intervention effects on youths' HLPs use.

It is possible that unmeasured risk and protective factors may have mediated Think Smart curriculum effects on HLPs and other drug use among youth in the study communities. For example, we noted that attitudes toward drug use and perceived risks were not considered mediators of the Think Smart study, although these risk factors have been posited as mediators of prevention intervention on problem behavior (e.g., Petraitis et al. 1995). Schinke et al. (2000) also listed attitudes toward drug use as a mediator; however, the authors did not report the mediation effects. Mediators from Jessor's Problem Behavior Theory may more accurately explain why the Think Smart curriculum reduced youths' use of inhalants and other harmful legal products (Donovan 2005). Jessor (1991) asserts that youth may participate in problem behaviors, including substance abuse, for purposeful reasons that are key to normal adolescent development—for example, to appear mature, to gain autonomy from parents, and to gain peers' approval. Others (Fleschler et al. 2002; Kurtzman et al. 2001) have noted that Jessor's Problem Behavior theory may help explain inhalant abuse as being only one problem within an “organized pattern of behaviors” that may include polydrug abuse and delinquency or crime.

An attempt was made in the current study to measure youths' drug refusal skills, but we could not establish acceptable validity and reliability of our measure. This is an important omission in that there have been studies that have found refusal skills to mediate the effects of a prevention intervention on drug use (e.g., Epstein and Botvin 2008). We also measured identity with Alaskan culture rather than bicultural competence among cultures in communities as Schinke did. This protective factor may have been an important unmeasured mediator in the current study.

An alternative explanation for positive reduction of HLPs use without the curriculum impacting the assumed mediators is that the small study communities became aware of the school-based curriculum focusing on harmful legal products, and therefore, reduced the availability to young youth mostly in the home and maybe to some extent in retail outlets and schools. This explanation is indirectly substantiated by a recent NIDA-funded feasibility study in four Alaska communities that showed a comprehensive prevention intervention including environmental strategies and an earlier version of the Think Smart curriculum reduced availability of HLPs (Courser et al. 2009; Gruenewald et al. 2009). The focus on reducing the availability of HLPs presents a plausible alternative prevention strategy in that HLPs are available from many different sources including those quite commonly encountered in adolescents' everyday lives. For example, they are available at local drug and convenience stores (e.g., over the counter medications), garages and tool bins around residences (e.g., volatile glues and gasoline products), and parents' purses and drug cabinets (e.g., prescription drugs).

The Think Smart curriculum did not reduce alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. It is possible that the curriculum emphasizes the use of HLPs much more than other drug use. Also, no intervention effects on alcohol and marijuana may have happened because of a low rate of 30-day use reported prior to implementing Think Smart—less than 2% of 30-day use.

In conclusion, this study has been implemented using the RCT gold standard criteria. We randomly assigned communities to experimental and controlled conditions. The outcomes were measured using student self-reported behavior, which is an accepted data source from a community and student sample with adequate power to detect statistically significant differences. Intervention fidelity was assessed using video cameras, which is the state of the art in intervention research, and these results documented adequate intervention fidelity. The study controlled for school system readiness differences to implement substance abuse interventions. The multi-level analysis strategy also takes into consideration variation across communities, and the repeated measures regression approach takes into consideration differences in baseline substance abuse.

Even with this high level of research rigor, the study is not without limitations. We have mentioned not being able to produce a valid and reliable measure of one of the key mediators in the conceptual framework. We also mention that our operational definition of cultural identity needs to be revisited to tap bicultural competence instead. In addition, we need to revisit the Think Smart curriculum to strengthen the content relating to drug use other than HLPs. Further, strengthening the method of delivery involving teacher training and lengthening the booster session to 6 months after implementation of the core curriculum may produce curriculum effects on the mediators.

These limitations, while important to address in future research, do not negate the result that the Alaska-adapted Think Smart curriculum did reduce the use of HLPs among young adolescents. Therefore, we recommend that it be tested in other communities in an effectiveness trial. Assuming positive results are produced from this study, the Think Smart curriculum should be adapted for other frontier areas of the U.S. and abroad (e.g., Canada or Australia).

Acknowledgments

Research for and preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant #R01 DA019640, K. Johnson, PI.

Contributor Information

Knowlton W. Johnson, Email: kwjohnson@pire.org, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Louisville Center, 1300 S. Fourth Street, Ste. 300, Louisville, KY 40208, USA.

Stephen R. Shamblen, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Louisville Center, 1300 S. Fourth Street, Ste. 300, Louisville, KY 40208, USA

Kristen A. Ogilvie, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Louisville Center, 1300 S. Fourth Street, Ste. 300, Louisville, KY 40208, USA

David Collins, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Louisville Center, 1300 S. Fourth Street, Ste. 300, Louisville, KY 40208, USA.

Brian Saylor, University of Alaska, Anchorage, Anchorage, AK, USA.

References

- Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission. Beyond the ABC's: Solvents/inhalants. 2004 Retrieved November 15, 2006, from http://corp.aadac.com/content/corporate/other_drugs/solvents_and_inhalants_beyond_abcs.pdf.

- Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Pollard JA. Student survey of risk and protective factors and prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use. Seattle, WA: Social Development Research Group, University of Washington and Developmental Research and Programs, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL. The public health impact of inhalant abuse; Paper presented at Inhalant Abuse among Children and Adolescents Consultation on Building and International Research Agenda; Rockville, Maryland. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bates SC, Plemons BW, Jumper-Thurman P, Beauvais P. Volatile solvent use: Patterns by gender and ethnicity among school attenders and dropouts. Drugs and Society. 1997;10:61–78. doi: 10.1300/J023v10n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ME, Walters ST, Miller JH, Woodall WG. Relationship of early inhalant use to substance use in college students. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12:227–240. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin G, Baker E, Renick N, Filazzola A, Botvin E. Preventing substance abuse by pre-teens: A cognitive–behavioral program. Digest of Alcoholism Theory and Application. 1985;4:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin G, Baker E, Dusenbury L, Tortu S, Botvin E. Preventing adolescent drug abuse through a multimodal cognitive–behavioral approach: Results of a 3-year study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990a;58:437–446. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin G, Baker E, Filazzola A, Botvin E. A cognitive–behavioral approach to substance abuse prevention: One-year follow-up. Addictive Behaviors. 1990b;15:47–63. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90006-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Ifill-Williams M. Preventing binge drinking during early adolescence: One- and two-year follow-up of a school-based preventive intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:360–365. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.15.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Daniel J, Balster RL. Deaths associated with inhalant abuse in Virginia from 1987 to 1996. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;53:239–245. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(98)00139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. The American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10:79–94. doi: 10.1080/105504901750160529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne A, Kirby B, Zibin T, Ensminger S. Psychiatric and neurological effects of chronic solvent abuse. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;36:735–738. doi: 10.1177/070674379103601008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance abuse treatment advisory, breaking news for the treatment field: Inhalants. 1. Vol. 3. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick OFD, Anderson HR. Neuropsychological consequences of volatile substance abuse: A review. Human Toxicology. 1989;8:307–312. doi: 10.1177/096032718900800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Courser M, Holder H, Collins D, Johnson K, Ogilvie K. Evaluating retailer behavior in preventing youth access to harmful legal products: A feasibility test. Evaluation Review. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0193841X08320940. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch BI, Caravati EM, Booth J. Trends in child and teen nonprescription drug abuse reported to a regional poison control center. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2004;61:1252–1257. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.12.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie SH, Reich T, Cloninger CR. Solvent use as a precursor to intravenous drug abuse. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1991;32:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(91)90005-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE. Problem behavior theory. In: Fisher CB, Lerner RM, editors. Encyclopedia of applied developmental science. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 872–877. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert AM, Liese BA, Powell BJ, Reed JS, Liskow BI. When alcoholics drink aftershave: A study of non-beverage alcohol consumers. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire) 1986;21:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ. Media resistance skills and drug skill refusal techniques: What is their relationship with alcohol use among inner-city adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleschler MA, Tortolero SR, Baumler ER, Vernon SW, Weller NF. Lifetime inhalant use among alternative high school students in Texas: Prevalence and characteristics of users. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:477–495. doi: 10.1081/ADA-120006737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist LD, Schinke SP, Trimble JE, Cvetkovich GT. Skills enhancement to prevent substance abuse among American Indian adolescents. International Journal of the Addictions. 1987;22(9):869–879. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Nichols TR, Doyle MM. Effectiveness of a universal drug abuse prevention approach for youth at high risk for substance use initiation. Preventive Medicine. 2003;36(1):1–7. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald P, Johnson KW, Shamblen SR, Collins DA, Ogilvie KA. Effects of community prevention to reduce legal product abuse—pre and post school survey results on self reported use, perceived availability, and other intermediate variables including intention to use. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44 doi: 10.3109/10826080902855223. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, McNeal RB., Jr How D.A.R.E. works: An examination of program effects on mediating variables. Health Education Behavior. 1997;24(2):165–176. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman J. The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection, and limited dependent variables and a sample estimator for such models. The Annals of Social and Economic Measurement. 1976;5:475–492. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 1979;47:153–161. doi: 10.2307/1912352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, Jenson JM. Inhalant abuse among antisocial youth. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:59–74. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, Walker RD, Walker PS, Cottler LB, Compton WM. Inhalant use among urban American Indian youth. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 1999;94:83–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Schutz CG, Anthony JC, Ensminger ME. Inhalants to heroin: A prospective analysis from adolescence to adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40:159–164. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K, Holder HD, Ogilvie K, Collins D, Courser M, Miller B et al. A community prevention intervention to combat inhalants and other harmful legal products among pre-adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 2007;37:227–247. doi: 10.2190/DE.37.3.b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug abuse: Overview of key findings, 2004. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2005. NIH Publication No. 05-5726. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Teen drug use continues down in 2006, particularly among older teens; but use of prescription-type drugs remains high. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan News and Information Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process evaluation: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review. 1981;5:602–619. doi: 10.1177/0193841X8100500502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman TL, Otsuka KN, Wahl RA. Inhalant abuse by adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:170–180. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Fendrich M. Inhalant use and delinquent behavior among adolescents: A comparison of inhalant users and other drug users. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 1999;94:555–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.19994455510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JC. Deaths related to the inhalation of volatile substances in Texas: 1988–1998. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:689–697. doi: 10.1081/ADA-100107662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Boyd CJ. Sources of prescription drugs for illicit use. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1342–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. The use, misuse and diversion of prescription stimulants among middle and high school students. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:1095–10116. doi: 10.1081/JA-120038031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;129:125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokrue K, Elias MJ, Bry BH. Dosage effect and the efficacy of a video-based teamwork-building series with urban elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2005;21:67–97. doi: 10.1300/J370v21n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Frontier Communities. List of frontier counties from 2000 US Census. 2007a Retrieved May 25, 2007, from http://frontierus.org/2000census.htm.

- National Center for Frontier Communities. The consensus definition—2007 update. 2007b Retrieved May 25, 2007, from http://www.frontierus.org/documents/consensus1.htm.

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Plested BA, Edwards RW, Kelly K, Beauvais F. Assessing community readiness for prevention. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1995;30:659–683. doi: 10.3109/10826089509048752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie DC, Coulehan HM, Ogilvie KA, Johnson KW. Think Smart: Problem solving for Alaskan Youth, A curriculum to prevent substance abuse including inhalants and other harmful everyday legal products (intermediate grades) Anchorage, AK: Akeela; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Partnership for a Drug Free America. (2005) The Partnership Attitude Tracking Study (PATS): Teens in Grades 7 through 12, 2005. 2006 May 16; [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay B, Miller TR. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models. 2nd. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt C, Bliss K. The cultural tailoring of a substance use prevention curriculum for American Indian youth. Journal of Drug Education. 2006;36:159–177. doi: 10.2190/369L-9JJ9-81FG-VUGV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor BL, Fair MD, Deike-Sims SL, Johnson KW, Ogilvie KA, Collins D. The use of harmful legal products among Alaskan pre-adolescents. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:425–436. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i5.18314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Diaz T, Griffin KW. Social skills, competence, and drug refusal efficacy as predictors of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Drug Education. 1999;29(3):251–278. doi: 10.2190/M3CT-WWJM-5JAQ-WP15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Orlandi MA, Botvin GJ, Gilchrist LD, Trimble JE, Locklear VS. Preventing substance abuse among American-Indian adolescents: A bicultural competence skills approach. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1988;35:87–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.35.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Tepavac L, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among Native American youth: Three-year results. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:387–397. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(99)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz CG, Chilcoat HD, Anthony JC. The association between sniffing inhalants and injecting drugs. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1994;35:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(94)90053-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skara S, Rohrbach LA, Sun P, Sussman S. An evaluation of the fidelity of implementation of a school-based drug abuse prevention program: Project Toward No Drug Abuse (TND) Journal of Drug Education. 2005;35:305–329. doi: 10.2190/4LKJ-NQ7Y-PU2A-X1BK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smitham DM, Slater MD, Luther NJ, Jumper-Thurman P. A comprehensive survey of solvent abuse prevention materials. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1999;45:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller HA. Epidemiology of volatile substance abuse (VSA) cases reported to U.S. poison centers. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:155–165. doi: 10.1081/ADA-120029871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Westergaard R, Anthony JC. Early onset inhalant use and risk for opiate initiation by young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. 2005 Retrieved July 8, 2008, from http://oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k5nsduh/2k5Results.pdf.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th. New York: Harper Collins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vinje G, Hewitt D. Influencing public health policy through action-oriented research: A case study of Lysol abuse in Alberta. Journal of Drug Issues. 1992;22:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND. What do we know about drug addiction. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1401–1402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Schlenger WE, Ringwalt CL. Use of nitrite inhalants (“poppers”) among American youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SJ, Longstaffe S, Tenenbein M. Inhalant abuse and the abuse of other drugs. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:371–375. doi: 10.1081/ADA-100101866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]