Abstract

Previously we identified associations between the mother’s air pollution exposure and birth weight for births in Connecticut and Massachusetts from 1999–2002. Other studies also found effects, though results are inconsistent. We explored potential uncertainties in earlier work and further explored associations between air pollution and birth weight for PM10, PM2.5, CO, NO2, and SO2. Specifically we investigated: (1) whether infants of younger (≤24 years) and older (≥40 years) mothers are particularly susceptible to air pollution’s effects on birth weight; (2) whether the relationship between air pollution and birth weight differed by infant sex; (3) confounding by co-pollutants and differences in pollutants’ measurement frequencies; and (4) whether observed associations were influenced by inclusion of pre-term births. Findings did not indicate higher susceptibility to the relationship between air pollution and birth weight based on the mother’s age or the infant’s sex. Results were robust to exclusion of pre-term infants and co-pollutant adjustment, although sample size decreased for some pollutant pairs. These findings provide additional evidence for the relationship between air pollution and birth weight, and do not identify susceptible sub-populations based on infant sex or mother’s age. We conclude with discussion of key challenges in research on air pollution and pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: air pollution, birth weight, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, particulate matter, PM10, PM2.5, pregnancy, sensitivity analysis, sulfur dioxide

1. Introduction

Several studies have examined the relationship between mother’s exposure to air pollution and birth weight or risk of low birth weight infants (Glinianaia et al 2004, Maisonet et al 2004, Šrám et al 2005, Triche and Hossain 2007). While results generally indicate that higher levels of air pollution are associated with lower birth weight, comparison across studies is hindered by variety in the study designs, the nature and quality of datasets, underlying populations, and pollution characteristics (Slama et al 2008). Our recent study of 358 504 births from 1999 to 2002 in Massachusetts and Connecticut identified associations between mother’s exposure over the gestational period to nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), and particulate matter with aerodynamic diameters <10 and 2.5 µm (PM10 and PM2.5), and birth weight (Bell et al 2007b). We found differential impacts of pollution on birth weight by race, with higher impacts for infants of Black/African–American mothers, a group already at risk for lower birth weight compared to Caucasian infants.

While our findings provide evidence for an association between maternal exposure to air pollution and risk of low birth weight, several critical questions remain. In particular, although we accounted for gestational age, our dataset included some pre-term births. While we address co-pollutants, we did not account for the different measurement frequency of various pollutants (Bell et al 2008, Salam 2008). A recent literature review summarized evidence on whether air pollution’s effect on pregnancy outcomes differ by gender (Ghosh et al 2007). The authors concluded that the limited research available indicated differential effects of air pollution on low birth weight by gender, but noted that further research was needed as this issue has not been extensively studied.

These issues are key concerns for not only our study, but also raise broader issues that are critical to understanding the literature on air pollution and pregnancy outcomes more broadly and underscore some of the challenges of such studies. Here we present results of analyses performed to address these limitations and uncertainties in previous work regarding co-pollutants and the inclusion of pre-term births in the dataset. We also investigate whether infants of younger or older mothers, sub-populations already at risk of low birth weight, are particularly susceptible to the effects of air pollution on birth weight, and compare the relationship between air pollution and birth weight by sex of the infant.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data on health, weather, and air pollution

This analysis is based on 358 504 births in Massachusetts and Connecticut from 1999 to 2002, except where a subset of the data is specified. Birth data were obtained from birth certificate registries from the Division of Vital Statistics, Reproductive Statistics Branch of the National Center for Health Statistics. For each subject, the birth certificate included data on the counties of birth and residence; mother’s and father’s ages and races; mother’s marital status, educational attainment, smoking use during pregnancy, and alcohol use during pregnancy; gestational age in weeks; child’s sex; birth weight; type of birth; prenatal care; and birth order. Observations missing these data were excluded. The dataset was limited to single births, gestational length of 32–44 weeks, and weights of 1000–5500 g.

Exposure was estimated based on an average of air pollutant and meteorological data in the county of mother’s residence, including only births for which exposure data were available for ≥75% of the weeks in each trimester. Births in counties without air pollution monitors were excluded. Air pollution data were obtained from the US Environmental Protection Agency, and weather data were obtained from the National Climatic Data Center. Further information can be found elsewhere (Bell et al 2007b).

2.2. Analytical approach

We applied a linear model incorporating birth weight as a continuous variable. All models included variables for child’s sex; mother’s education, tobacco use, marital status, age, and race; prenatal care; birth order; type of birth (e.g., vaginal, cesarean section); apparent temperature, which incorporates temperature and dew point temperature, at each trimester; year; and gestational length. Additional information on the methods and dataset are available elsewhere (Bell et al 2007b).

In our initial study, results of the linear model indicate that higher mother’s exposure to NO2, CO, PM10, and PM2.5 were associated with lower birth weight. No association was observed between gestational exposure to sulfur dioxide (SO2) and birth weight. We conducted four sets of analysis to further investigate the relationship between air pollution and birth weight to consider the impact of: (1) differential effect based on mother’s age; (2) differential effect by infant’s sex; (3) adjustment by co-pollutants; and (4) exclusion of pre-term births in the analysis.

To investigate effects by mother’s age, we constructed a model with a variable for the pollutant of interest, an indicator for mother’s age by strata, and interaction terms for the pollutant and the indicators of mother’s age. The age strata were ≤24, 25–29, 30–39, and ≥40 years, with 30–39 years used as the reference category. Earlier work found that the risk of low birth weight was similar for infants of mothers ages 30–35 and 36–39 years or for infants of mothers ages <20 and 20–24 years (Bell et al 2007b). We examined differential air pollution effects by mother’s age for the pollutants demonstrating an association with birth weight in the non-interaction gestational exposure model (PM10, PM2.5, NO2, and CO).

We examined whether the association between air pollution and birth weight differed by sex of infant by repeating analysis for the pollutants demonstrating a relationship in the total dataset (PM10, PM2.5, NO2, and CO) with a subset of data representing female infants only, and then with a dataset representing males only.

Earlier work included multivariate models to consider potential confounding by co-pollutants for pairs of co-pollutants that were not highly correlated (Bell et al 2007b). These results indicated that the single pollutant model results were robust to adjustment by other pollutants. However, data for all pollutants were not available for all study subjects (Salam 2008). As a function of the distribution of monitoring networks, exposure estimates may be available for some pollutants but not others, raising challenges to the study of multiple pollutants simultaneously. We generated a new dataset for each pair of pollutants considered in co-pollutant adjustment by including only observations for which data are available for both pollutants. Potential confounding by co-pollutants was estimated by generating effect estimates for the relationship between exposure to a given air pollutant and birth weight based on three combinations of model structures and datasets, represented by the rows of table 1.

Table 1.

Model structures and datasets used in co-pollutant analysis.

| Pollutant variables included in the model |

Days included in the analysis |

|---|---|

| Pollutant of interest | Days with data for the pollutant of interest |

| Pollutant of interest | Days with data for the pollutant of interest and the potential confounder |

| Pollutant of interest and potential confounder pollutant | Days with data for the pollutant of interest and the potential confounder |

The first row represents a model including the pollutant of interest and no variables for other pollutants, for a dataset with all observations for which gestational exposure data were available for that specific pollutant. The second row also includes the pollutant of interest and no variables for other pollutants, but for the subset of observations for which gestational exposure data were available for that specific pollutant and the potential confounder of interest. The final model contains variables for both the pollutant and the co-pollutant and is based on observations with data for both those pollutants. For example, we calculated the association between PM2.5 and birth weight for all births with PM2.5 data without adjusting by co-pollutants, the association between PM2.5 and birth weight without co-pollutant adjustment but considering only the subset of births with CO data available, and the association between PM2.5 and birth weight adjusted by CO.

Our initial analysis addressed gestational length by omitting births with gestational length <32 weeks or >44 weeks, and by adjusting all models for gestational length at 2-week intervals (32–34, 35–36, 37–38, 39–40, 41–42, and 43–44 weeks) (Bell et al 2007b). Sensitivity analyses concluded that the initial results identifying associations between gestational exposure and air pollution were robust to models with gestation specified at 1-week intervals (data not shown).

This original dataset included births that meet the clinical definition of pre-term (<37 weeks). We performed new analysis by restricting the observations to only those births with 37–44 weeks gestation and generated effect estimates for gestational exposure and each trimester. The inclusion of only births at gestations of 37–44 weeks is consistent with several previous studies (Basu et al 2004, Maisonet et al 2001, Ritz and Yu 1999, Salam et al 2005). Trimesters were defined as 1–13 weeks, 14 to 26 weeks, and 27 weeks to birth. We applied a linear model with separate variables for each trimester’s exposure. As concentrations of pollutants can be correlated across trimesters, we also implemented a model that includes the exposure level for a specified trimester, and the exposure levels for the remaining two trimesters adjusted for the initially specified trimester’s exposure, repeated for each model as the specified trimester. Additional details on this modeling structure are provided elsewhere (Bell et al 2007b). Effect estimates for trimester exposure were based on results that were consistent across all the trimester models.

3. Results

3.1. Differential impact of air pollution on birth weight by mother’s age

Our results did not identify susceptibility to the association between air pollution and low birth weight based on mother’s age. The infants of the older mothers (≥40 years) or younger mothers (≤24 years or 25–29 years) did not exhibit relationships with air pollution and birth weight statistically different from those of the reference category (age 30–39 years). Figure 1 shows the change in birth weight in grams for an interquartile increase in gestational pollutant exposure for infants of the youngest and oldest age group, compared to the change in birth weight for the same increment of pollution for the reference age group (30–39 years). These results indicate the change in birth weight for infants of the mothers in the youngest and oldest age categories beyond the change in birth weight experienced by infants with mothers 30–39 years. Results do not indicate that infants of the older or younger mothers are particularly susceptible to the association between air pollution and birth weight, in that effects for these groups were not statistically different from the middle-age category.

Figure 1.

Difference in the change in birth weight (gm) for an interquartile increase in pollutant exposure over the gestational period for infants of the youngest (<25 years) and oldest (>39) mothers, compared to the change in birth weight for the same increment in pollution for infants of mothers ages 30–39 years. (Note: the point reflects the central estimate; the vertical line represents the 95% confidence interval.)

3.2. Differential impact of air pollution on birth weight by infant’s sex

In our dataset, 51.1% of subjects were male infants and 48.9% female. Males had higher birth weights. Results from stratified models with male only or female only infants revealed no differences in the relationship between air pollution and birth weight by infant sex. Table 2 shows the change in birth weight per interquartile (IQR) increase in pollutant over gestational exposure for the entire dataset and for male and female infants separately. The association between air pollutants and birth weight was statistically significant for either males or females alone (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Difference in birth weight (gm) per IQR increase in pollution for the gestational period (95% confidence interval), by infant sex (Note: the interquartile range (IQR) refers to the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile.)

| Pollutant (IQR) | All infants | Male infants only | Female infants only |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 (4.8 ppb) | −8.9(−10.8, −7.0) | −8.7(−11.4, −6.0) | −9.0(−11.7, −6.4) |

| CO (303 ppb) | −16.2(−19.7, −12.6) | −16.6(−21.6, −11.7) | −15.6(−20.6, −10.6) |

| PM10 (7.4 µg m−3) | −8.2(−11.1, −5.3) | −7.2(−11.3, −3.1) | −9.3(−13.4, −5.2) |

| PM2.5 (2.2 µg m−3) | −14.7(−17.1, −12.3) | −15.4(−18.9, −11.9) | −14.4(−17.8, −10.9) |

3.3. Co-pollutant adjustment

For pollutant pairs that were not highly correlated we performed co-pollutant adjustment with the multiple model structures listed above. For instance, for models analyzing the effects of PM10 or PM2.5, we adjusted for CO and SO2. We did not adjust PM10 by PM2.5 or vice versa as PM2.5 is a subset of PM10 and their concentrations co-vary (correlation 0.77, p-value <0.001). As the monitoring networks differ by pollutant, inclusion of multiple pollutants reduced the sample size. For analysis of PM10, adjusting by CO and SO2 reduced the sample size by 4.4 and 3.5%, respectively. Figure 2 shows the sample size available for the single and two pollutant models. The largest reduction in sample size was for PM2.5 with adjustment for CO or SO2, for which 30% and 28% of the CO observations did not have co-pollutant exposure data.

Figure 2.

Number of observations available for analysis in single and two pollutant models. (Note: each bar provides the per cent of births from the entire dataset with data for the specified pollutant combination.)

Figure 3 shows the reduction in birth weight for an interquartile increase in mother’s exposure to pollutant over the gestational period, with and without co-pollutant adjustment. Results from three types of models are included: (1) single pollutant model, shown with boxes and solid lines; (2) single pollutant model based on the subset of data for which exposure data on the co-pollutant are available, shown with circles and solid lines; and (3) two pollutant model (i.e., the effect estimate for one pollutant, adjusted by another pollutant), shown as circles with dashed lines. Comparison of models with and without co-pollutant adjustment, based on the same dataset, can be made by examining model types 2 and 3. The association between air pollutant exposure and birth weight persists with adjustment by co-pollutants, and remains statistically significant in all cases. The magnitude of the effect is generally lower with co-pollutant adjustment, but not in all cases.

Figure 3.

Change in birth weight per IQR increase in gestational exposure to pollutant, for single and two pollutant linear models. (Note: the point reflects the central estimate; the vertical line represents the 95% confidence interval. Models without co-pollutant adjustment are shown with solid lines; models adjusted by co-pollutants are shown with dashed lines.)

3.4. Impact of pre-term births

We performed sensitivity analysis by restricting observations to those with a gestational period of 37–44 weeks. Births with gestational length of 32–36 weeks accounted for 6.7% of the original observations; therefore the restricted dataset contained 334 305 births. Effects estimates based on gestational exposure from the subset analysis (37–44 weeks) were very similar to those from the original analysis (32–44 weeks), as shown in table 3, indicating that the original results are not an artifact of inclusion of pre-term births.

Table 3.

Difference in birth weight (gm) per IQR increase in pollution for the gestational period (95% confidence interval), for different datasets based on gestational age. (Note: the interquartile range (IQR) refers to the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile.)

| Pollutant (IQR) | Observations withh 32–44 weeks gestation |

Observations with 37–44 weeks gestation |

|---|---|---|

| NO2 (4.8 ppb) | −8.9(−10.8, −7.0)a | −9.0(−10.9, −7.0)a |

| CO (303 ppb) | −16.2(−19.7, −12.6)a | −14.7(−18.3, −11.1)a |

| SO2 (1.6 ppb) | −0.9(−4.4, 2.6) | −0.7(−4.3, 2.9) |

| PM10 (7.4 µg m−3) | −8.2(−11.1, −5.3)a | −9.0(−11.9, −6.0)a |

| PM2.5 (2.2 µg m−3) | −14.7(−17.1, −12.3)a | −14.7(−17.2, −12.2)a |

p < 0.001.

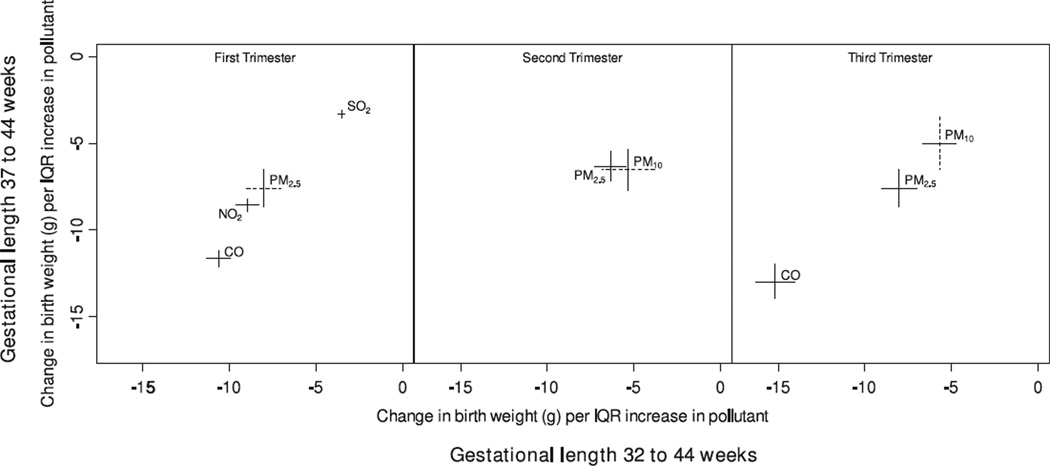

Figure 4 compares trimester results from the original analysis including births with gestational length of 32–44 weeks, to results from the sensitivity analysis with births with gestational length of 37–44 weeks. Each line plots the range of effect estimates across the trimester models. Results from the original and new analysis are similar; although there are differences in statistical significance. The new analysis finds statistically significant relationships between birth weight and PM2.5 at the first trimester and PM10 at the second trimester. The original analysis found similar effect estimates for these pollutants and trimesters (p < 0.06 for PM2.5, p < 0.08 for PM10). Estimates for PM10 in the third trimester under the new analysis had p < 0.08. Trimester results based on the sensitivity analysis (subset of births with 37–44 weeks gestation) were similar to original results (births with 32–44 weeks gestation).

Figure 4.

Change in birth weight per IQR increase in trimester exposure to pollutant, with and without inclusion of pre-term births. (Note: each line represents the range of results across the trimester models. The horizontal line reflects results based on births with gestational length 32–44 weeks; the vertical line reflects results based on births with gestational length of 37–44 weeks. Dotted lines indicate that results were not statistically significant across all trimester models. Results for a pollutant and trimester without statistically significant results are not shown.)

4. Discussion

Findings indicate that while some populations are at higher risk of low birth weight (e.g., infants of younger or older mothers, female infants), the relationship between air pollution and low birth weight did not differ by mother’s age or infant’s sex. Although only limited research has been conducted on these topics, our results contrast earlier work indicating a higher association between air pollution and risk of low birth weight for males compared to females for a total suspended particles (TSP) and SO2 pollutant indicator (Rogers et al 2000), TSP (Wang et al 1997), and PM10 and NO2 (Wilhelm and Ritz 2003). At term, male infants are typically not as developed as female infants, and this differential development could play a role in potential interaction between air pollution and birth weight (Ghosh et al 2007). Even with our new analysis, there exists limited findings on this issue and further investigation is warranted.

Analysis found that results were robust to co-pollutant adjustment, with analysis restricted to observations with data for multiple pollutants to allow a comparison across identical datasets. Results were further robust to exclusion of pre-term births, with models identifying the same suite of pollutants and similar effect estimates. While these sensitivity analyses provide confidence in our results, they also highlight challenges to research on air pollution and pregnancy outcomes, and in fact to the study of air pollution and human health effects more broadly. Exposure to air pollution in epidemiological settings typically is estimated from data based on existing regulatory monitors. Therefore, not all regions of interest may have monitoring data available for all pollutants. In our study, the reduction in sample size for two pollutant models did not greatly affect results, although the lack of exposure information did prevent us from analyzing some births, or from analyzing co-exposure in some locations. For Massachusetts and Connecticut, based on 2007 monitor locations, county-level exposures can be estimated for 56.7, 62.5, 47.9, 55.2, and 69.6% of the total population for NO2, CO, SO2, PM10, and PM2.5, respectively (US Census Bureau 2007, US EPA 2007). Only 29.4% of the population has data for all of these pollutants, and no monitors for any of these pollutants are located in the counties of 12.5% of the population. As research evolves to consider the health burden of the overall air pollutant mixture, the lack of co-located air pollutant measurements will become increasingly prohibitive.

An additional challenge in multi-pollutant analysis is the relationship between multiple pollutants, with some pollutants functioning as precursors to others (e.g., NO2 as a precursor to ozone); the heterogeneity in the chemical composition of particulate matter, which is in itself a complex air pollutant mixture (Bell et al 2007a); and the high correlation of some pollutants due to similar sources (e.g., traffic as sources of CO and PM2.5). By definition, PM2.5 is a subset of PM10, making separation of the effects of these pollutants quite challenging. While our research indicates associations with birth weight and both PM2.5 and PM10, information on which size distributions, chemical components, and sources of particles are most toxic is a necessary topic of further research. Another limitation to this work, and much air pollution human health research, is that pollution exposures were based on county-wide estimates, which do not account for within-county heterogeneity of pollutant levels or differences among individuals’ exposures, such as due to occupational exposure, housing structure, or indoor/outdoor activity patterns.

Exposure estimates are further hindered by the ‘snapshot’ nature of many data sources, such as the birth certificates used in this study. Studies of the residential mobility of pregnant women provide varying results, identifying 12% (Fell et al 2004) to 33% (Canfield et al 2006) of pregnant women moving during pregnancy, although other research found that most moves were within the same county and that exposure based on the residence at time of delivery is an appropriate measure for county-level exposures (Shaw and Malcoe 1992). Still measurement error is introduced by the assumption that exposure based on residence at time of birth is applicable to the entire gestational period. Such measurement error is larger for first trimester estimates than for third trimester estimates. Measurement error may also change throughout pregnancy if the indoor/outdoor activity patterns change. A recent study found that more time was spent indoors later into pregnancy (Nethery et al 2008a).

A variety of techniques have been developed to address some of these concerns. Factor analysis and other source apportionment techniques have been used to separate particulate matter effects into the contribution from different sources (Duvall et al 2008, Laden et al 2000, Thurston et al 2005), and some work has examined the impact of specific particulate chemical components on health (Ostro et al 2007 and 2008). Air quality models can be used to estimate pollutant concentrations in areas or time periods for which monitoring data do not exist (Bell 2006, Sanhueza et al 2003). Other exposure estimates such as proximity to traffic or land-use modeling have been used in exposure estimations (Gauderman et al 2005, Nethery et al 2008b, Ryan et al 2007). These techniques could be applied to study of air pollution and birth outcomes. Brauer et al (2008) found that residence within 50 m of a highway was associated with higher risk of small for gestational age and low birth weight infants. Slama et al (2007) supplemented ambient pollution levels with data on land-use, population density, and features of the roadways in a study of birth weight.

While the analysis here provides additional evidence for the impact of air pollution on birth weight, several questions remain unanswered, such as a full understanding of the physiological mechanism by which a pollutant, or set of pollutants, could result in lower birth weight infants (Slama et al 2008). Challenges inherent to the study of air pollution and pregnancy outcomes include the difficulties in estimating exposure as discussed above, as well as discrepancies of data characteristics across multiple studies (e.g., different data types for prenatal care), which hinder comparison and synthesis of results. Additional research is needed to gain a better understanding of the impacts of air pollution on pregnancy outcomes, including identification of susceptible sub-populations, effects of multiple pollutants, and results in various locations and time periods with different study designs.

Acknowledgments

Funding for MLB and KE was provided by the Health Effects Institute through the Walter A Rosenblith New Investigator Award (4720-RFA04-2/04-16). Funding for MLB was also provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Outstanding New Environmental Scientist (ONES) Award (R01 ES015028). Funding for KB was provided by NIEHS (ES07456-07, ES11013).

References

- Basu R, Woodruff TJ, Parker JD, Saulnier L, Schoendorf KC. Comparing exposure metrics in the relationship between PM2.5 and birth weight in California. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 2004;14:391–396. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML. The use of ambient air quality modeling to estimate individual and population exposure for human health research: a case study of ozone in the Northern Georgia region of the United States. Environ. Int. 2006;32:586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, Dominici F, Ebisu K, Zeger SL, Samet JM. Spatial and temporal variation in PM2.5 chemical composition in the United States for health effects studies. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007a;115:989–995. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, Ebisu K, Belanger K. Ambient air pollution and low birth weight in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007b;115:1118–1125. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, Ebisu K, Belanger K. Air pollution and birth weight: Bell et al respond. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:A106–A107. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer M, Lencar C, Tamburic L, Koehoorn M, Demers P, Karr C. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution impacts on birth outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:680–686. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield MA, Ramadhani TA, Langlois PH, Waller DK. Residential mobility patterns and exposure misclassification in epidemiologic studies of birth defects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2006;16:538–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.jes.7500501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall RM, Norris GA, Dailey LA, Burke JM, McGee JK, Gilmour MI, Gordon T, Devlin RB. Source apportionment of particulate matter in the US and associations with lung inflammatory markers. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008;20:671–683. doi: 10.1080/08958370801935117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell DB, Dodds L, King WD. Residential mobility during pregnancy. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2004;18:408–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Lurmann F, Kuenzli N, Gilliland F, Peters J, McConnell R. Childhood asthma and exposure to traffic and nitrogen dioxide. Epidemiology. 2005;16:737–743. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181308.51440.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R, Rankin J, Pless-Mulloli T, Glinianaia S. Does the effect of air pollution on pregnancy outcomes differ by gender? A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2007;105:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Bell R, Pless-Mulloli T, Howel D. Particulate air pollution and fetal health: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiology. 2004;15:36–45. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000101023.41844.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laden F, Neas LM, Dockery DW, Schwartz J. Association of fine particulate matter from different sources with daily mortality in six U.S. cities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000;108:941–947. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonet M, Bush TJ, Correa A, Jaakkola JJ. Relation between ambient air pollution and low birth weight in the northeastern United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001;109(suppl 3):351–356. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonet M, Correa A, Misra D, Jaakkola JJ. A review of the literature on the effects of ambient air pollution on fetal growth. Environ. Res. 2004;95:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nethery E, Brauer M, Janssen P. Time-activity patterns of pregnant women and changes during the course of pregnancy. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2008a doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.24. at press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nethery E, Teschke K, Brauer M. Predicting personal exposure of pregnant women to traffic-related air pollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 2008b;395:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B, Feng WY, Broadwin R, Green S, Lipsett M. The effects of components of fine particulate air pollution on mortality in California: results from CALFINE. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:13–19. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B, Feng WY, Broadwin R, Malig B, Green S, Lipsett M. The impact of components of fine particulate matter on cardiovascular mortality in susceptible subpopulations. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008 doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.036673. at press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz B, Yu F. The effect of ambient carbon monoxide on low birth weight among children born in southern California between 1989 and 1993. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999;107:17–25. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9910717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JF, Thompson SJ, Addy CL, McKeown RE, Cowen DJ, Decouflé P. Association of very low birth weight with exposures to environmental sulfur dioxide and total suspended particulates. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000;151:602–613. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PH, et al. A comparison of proximity and land use regression traffic exposure models and wheezing in infants. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:278–284. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam MT. Air pollution and birth weight in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:A106. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam MT, Millstein J, Li YF, Lurmann FW, Margolis HG, Gilliland FD. Birth outcomes and prenatal exposure to ozone, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter: results from the Children’s Health Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:1638–1644. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza PA, Reed GD, Davis WT, Miller TL. An environmental decision-making tool for evaluating ground-level ozone-related health effects. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2003;53:1448–1459. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2003.10466324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, Malcoe LH. Residential mobility during pregnancy for mothers of infants with or without congenital cardiac anomalies: a reprint. Arch. Environ. Health. 1992;47:236–238. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1992.9938355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slama R, Morgenstern V, Cyrys J, Zutavern A, Herbarth O, Wichmann HE, Heinrich J The LISA Study Group. Traffic-related atmospheric pollutants levels during pregnancy and offspring’s term birth weight: a study relying on a land-use regression exposure model. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:1283–1292. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slama R, et al. Meeting report: atmospheric pollution and human reproduction. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:791–798. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šrám RJ, Binková B, Dejmek J, Bobak M. Ambient air pollution and pregnancy outcomes: a review of the literature. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:375–382. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston GD, et al. Workgroup report: workshop on source apportionment of particulate matter health effects: intercomparison of results and implications. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:1768–1774. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triche EW, Hossain N. Environmental factors implicated in the causation of adverse pregnancy outcome. Sem. Perinatol. 2007;31:240–242. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. [Accessed 1 Oct 07];2006 Population Estimates. 2007 http://www.census.gov/popest/estimates.php.

- US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) AirData. [Accessed 1 Oct 07];2007 http://www.epa.gov/air/data/

- Wang X, Ding H, Ryan L, Xu X. Association between air pollution and low birth weight: a community-based study. Environ. Health Perspect. 1997;105:514–520. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm M, Ritz B. Residential proximity to traffic and adverse birth outcomes in Los Angeles County, California, 1994–1996. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003;111:207–216. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]