Abstract

Photochromic indolylfulgimides covalently attached to polymers have beneficial properties for optical switching. A 3-indolylfulgide and two 3-indolylfulgimides with one or two polymerizable styrene groups attached on the nitrogen atom(s) were synthesized. Copolymerization with methyl methacrylate (MMA) provided linear copolymers (one styrene group) or a cross-linked copolymer (two styrene groups). The properties of the monomers and copolymers in toluene or as thin films were characterized. The new copolymers were photochromic (reversible Z-to-C isomerization), absorbed visible light, and revealed good thermal and photochemical stability. At room temperature, all copolymer films showed no loss of absorbance after 5 weeks. At 80 °C in either toluene or as films, the Z-forms copolymers were less stable than the C-form copolymers, which showed little or no degradation after 400 h. The degradation rate due to repeated ring-closing – ring opening cycles was less than 3% per 100 cycles. The cross-linked copolymer showed photochemical stability comparable to monomeric fulgides in toluene, <1% per 100 cycles. In general, the properties of the linear and cross-linked copolymers were similar to the corresponding monomers in toluene. In films, the conformations of the Z-form were restricted due to the matrix indicating that the preparation of films from the C-form is advantageous.

Keywords: photochromism, 3-indolylfulgimide, cross-linked copolymer, thin films

1. Introduction

Fulgides and fulgimides are photochromic compounds with many attractive properties and potential applications. Their photochromism is characterized by a reversible, light-induced transformation between the open and closed forms, as shown in Scheme 1 for fluorinated 3-indolylfulgides/indolylfulgimides [1,2]. Fluorinated 3-indolylfulgides and indolylfulgimides have high thermal and photochemical stability, large quantum yields, large molar absorption coefficients, absorption maxima in the visible region [3–5], and, in the case of fulgimides, stability in aqueous solution [6,7]. The reversible change between two thermally stable states with different structures and colors allows fulgides and fulgimides to be used as optical switches in information storage devices and biological sensors [2].

Scheme 1.

Photochromism of fluorinated 3-indolylfulgide/indolylfulgimide.

Applications of photochromic compounds convert the reversible changes in structure associated with photochromism into reversible changes in properties [8–16]. In practice, photochromic molecules are almost always covalently attached to other entities, such as a synthetic polymer, biological macromolecule, or enzyme substrate. Covalent attachment to synthetic polymers, especially cross-linked polymers, minimizes aggregation and diffusion of the photochromic molecules compared to embedding [17–19]. Photochromic synthetic polymers have a broad range of applications as their properties such as viscosity, shape, and membrane permeability, can be varied to suit a particular purpose [20,21]. Polymers containing azobenzenes, diarylethenes, and fulgimides have been used in information storage [22,23], as “on”/”off” switches in biological systems [20–22,24–30], and surface patterning [16].

Fulgides and fulgimides have been attached to synthetic polymers, however the polymers were initially prepared using the open form of the fulgide or fulgimide. Rentzepis et al. reported photochromic linear and cross-linked copolymers of methyl methacrylate and 2-indolylfulgimides with pendant vinyl benzenes [17,18]. These copolymers had similar properties as the corresponding monomeric 2-indolylfulgimides. The copolymers were photochromic, stable at room temperature, and lost less than 10% of their color after cycling back and forth between the open and closed form 100 times. Ramamurthy et al. attached 2-indolylfulgimide to methyl methacrylate using click chemistry and then prepared a linear polymer that was photochromic [31]. Kannan et al. prepared linear copolymers by copolymerized methyl methacrylate with a pendant 2-indolylfulgimide and methyl methacrylate with pendant azobenzenes [32]. The polymer could be cycled back and forth between the two fulgimide forms at least 20 times and the copolymer had similar properties as a film and in solution, and as the corresponding monomers. As expected, the azobenzene was thermally unstable while the fulgimide was thermally stable.

Thermal stability, efficiency, and photochemical stability are all important for practical application. Although fulgimide copolymers have been prepared previously, no reports of thermal stability at elevated temperatures or a comparison of polymers prepared in the open and closed forms have appeared. In addition, the ability of the copolymers to cycle back and forth could be improved. Knowledge of thermal stability is essential for electronic devices which are rated to operate at elevated temperatures. Preparation of copolymers in the open form is more facile as purification of the closed form is not required, however, photochromic polymers prepared in the open form may not be as efficient due to conformational restrictions, as is the case for diarylethenes [33]. We also expect significantly enhanced photochemical stability due to the incorporation of trifluoromethyl group in the monomer structure [5].

Herein, we prepared linear and cross-linked photochromic copolymers of 3-indolylfulgide and 3-indolylfulgimides with pendant styrene group(s) (1–3, using both the open and closed forms) (Scheme 2) and methyl methacrylate. Their optical properties, and photochemical and thermal stability in toluene and as films were characterized. Comparisons are made with and between the corresponding monomeric fulgides and fulgimides (1–4) (Scheme 2). The photochemical stability and the thermal stability of the photochromic response for linear and cross-linked fulgimide polymers are quantitatively determined.

Scheme 2.

A 3-indolylfulgide (1) and 3-indolylfulgimides (2 and 3) with pendant styrene groups and the parent trifluoromethylindoylfulgide (4).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Procedures and Materials

All commercially available materials were used without purification. Fulgide 4 and dimethyl isopropylidenesuccinate 8 were synthesized as described previously [34]. NMR spectra were recorded on a Brücker 400 MHz NMR spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR samples were internally referenced to TMS. UV-Vis spectra were recorded with a Cary 300 spectrophotometer. The HRMS were obtained at the University of Florida. Flash chromatography was performed with 230 – 400 mesh silica gel. Illumination was provided by a 1000 W Hg (Xe) arc lamp with a water filter followed by a hot mirror followed by either a bandpass filters (436 nm (for fulgide)/405 nm (for fulgimides)) or a cutoff filters (>570 nm (for fulgide)/515 nm (for fulgimides)). The molecular weights of copolymers were determined by gel permeation chromatography.

2.2. Synthesis of monomers

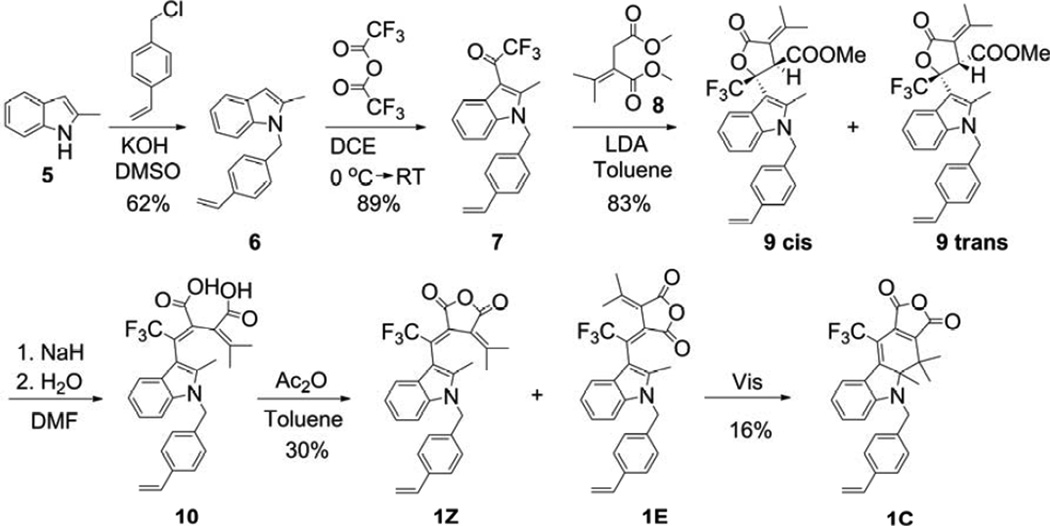

2.2.1. Synthesis of fulgide 1 (Scheme 3)

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of fulgide 1.

2-methyl-1-(4-vinylbenzyl)indole (6) [17]

2-Methylindole (5) (20.96 g, 160 mmol) was added to a suspension of potassium hydroxide (40.80 g, 728 mmol) in 320 mL of DMSO, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 45 min. After cooling to 0 °C, 4-vinylbenzyl chloride (26.25 g, 172 mmol) was added to the mixture dropwise. The mixture was left to stir at room temperature for 1.5 h and then poured onto 100 g of crushed ice in an Erlenmeyer flask. After 24 h at room temperature, the mixture was diluted with 2.5 L of water, and the aqueous layer was extracted with methylene chloride (3 × 500 mL). The combined organic layers were back extracted with 1 L of water, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane as a solvent) to afford a white solid (24.44 g, 62%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.58-7.53 (m, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.21-7.16 (m, 1H), 7.12-7.04 (m, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.65 (dd, J = 17.6, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 6.32 (s, 1H), 5.68 (dd, J = 17.5, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 5.28 (s, 2H), 5.20 (dd, J = 10.9, 0.4 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 137.5, 137.2, 136.73, 136.65, 136.3, 128.2, 126.6, 126.2, 120.8, 119.7, 119.5, 113.9, 109.2, 100.5, 46.3, 12.7. C18H17N HRMS (ESI) m/z: 248.1436 [obtained M + H]+, 248.1434 [calculated M + H]+.

2-methyl-1-(4-vinylbenzyl)-3-trifluoroacetylindole (7)

Trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA) (31.10 g, 148.3 mmol) was poured into a 500 mL round-bottom flask, and 170 mL of 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) was added. The flask was then placed in an ice-water bath and cooled to 0 °C. 2-Methyl-1-(4-vinylbenzyl)indole (6) (24.44 g, 98.9 mmol) dissolved in 100 mL of DCE was added to the TFAA solution dropwise over 45 min via an addition funnel, and the reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature. After stirring for 1 h under argon, the mixture was quenched with a saturated NaHCO3 solution (300 mL) and then extracted with methylene chloride (2 × 150 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. A white solid was afforded (30.09 g, 89%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 8.09 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.40 – 7.20 (m, 5H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.66 (dd, J = 17.6, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.40 (s, 2H), 5.25 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 2.76 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 175.7 (q, J = 36 Hz), 150.0, 137.6, 136.7, 136.0, 134.5, 127.0, 126.2, 125.3, 123.5, 123.4, 121.1 (q, J = 4 Hz), 117.2 (q, J = 290 Hz), 114.6, 110.2, 108.5, 46.7, 13.3. C20H16F3NO HRMS (ESI) m/z: 344.1262 [obtained M + H]+, 344.1257 [calculated M + H]+.

3-[2-methyl-1-(4-vinylbenzyl)-3-trifluoroindolylethylidene]-3-isopropylidene succinic anhydride (1)

Dimethyl isopropylidenesuccinate (8) (13.6 g, 73 mmol) was dissolved in 400 mL of toluene in a 1 L round-bottom flask, and then the solution was concentrated to 300 mL. To the stirred solution under argon, lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) (29.2 mL of a 2 M solution in THF, 58.4 mmol) was added dropwise over 20 min via an addition funnel. To avoid moisture in the reaction mixture, a cannula was used to fill the addition funnel from the bottle with LDA. To the succinate/LDA/toluene solution, 2-methyl-1-(4-vinylbenzyl)-3-trifluoroacetylindole (7) (5.0 g, 14.6 mmol) dissolved in toluene (50 mL) was added dropwise over 15 min via an addition funnel, and the reaction mixture was left to stir under argon. After 1.5 h, the mixture was quenched with 200 mL of 5% H2SO4, and the acidic layer was extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 300 mL). The organic layers were combined, extracted with water (2 × 300 mL), dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (3:1 methylene chloride/hexane as eluent) and then recrystallized from ethanol to provide 5.9 g (83%) of a cis/trans mixture of indolelactones (9). DMF (100 mL) was added into a 250 mL round-bottom flask and cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. The cis/trans mixture of indolelactones (9) (2.0 g) and sodium hydride (60% dispersion in oil, 0.64 g, 16.08 mmol) were added to the flask, and the mixture was warmed to room temperature and allowed to react for 1.5 h. Water (300 µL) was added, and the reaction mixture was left to stir for 12 h. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo until only solid remained, and the solid was partitioned between 0.1 M NaOH (100 mL) and EtOAc (100 mL). The aqueous layer was acidified with 5% H2SO4 and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 150 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to afford 2.20 g of the crude diacid (10), which was then suspended in 50 mL of toluene. Acetic anhydride (20 mL, 210 mmol) was added, and the mixture was left to react at 35 °C for 1 h and then concentrated in vacuo. The resulting crude fulgide was purified by column chromatography with toluene as the eluent to provide a Z/E mixture. To prepare pure Z-form, the Z/E mixture in toluene was illuminated with 436 nm light until photostationary state (PSS) was reached. The PSS solution in toluene was then illuminated with 570 nm light to obtain the crude Z-form solution. Toluene was removed in vacuo and recrystallization from CH2Cl2/hexane provided 0.68 g of the Z-form fulgide (30%). Z-form: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.36 – 7.25 (m, 4H), 7.25 – 7.16 (m, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.66 (dd, J = 17.6, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.36 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.26 (d, J = 10.9 Hz, 1H), 5.25 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 161.7, 160.6, 159.5, 137.5, 137.3, 136.8, 135.9, 135.8, 132.8 (q, J = 35 Hz), 128.6, 126.8, 126.5, 124.9, 122.8, 122.0 (q, J = 278 Hz), 121.6, 120.4, 119.6, 114.6, 109.8, 107.8, 47.0, 26.9, 23.1, 12.2. C27H22F3NO3 HRMS (ESI) m/z: 466.1646 [obtained M + H]+, 466.1625 [calculated M + H]+. Pure C-form was prepared from the PSS solution, toluene was removed in vacuo, and the C-form was purified by column chromatography (toluene as an eluent) followed by the recrystallization from CH2Cl2/hexane to provide 0.48 g of the C-form fulgide (16%). C-form: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (td, J = 7.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (dd, J = 17.6, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.46 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 162.8, 162.5 (q, J = 3.6 Hz), 160.9, 159.7, 141.8, 138.1 (q, J = 1.5 Hz), 137.0, 136.32, 136.24, 136.16, 128.7 (q, J = 7 Hz), 126.9, 126.6, 122.2 (q, J = 273 Hz), 120.4, 119.3, 114.3, 110.9, 105.6 (q, J = 38 Hz), 76.7, 50.8, 39.1, 19.5, 18.2, 16.4. C27H22F3NO3 HRMS (ESI) m/z: 466.1641 [obtained M + H]+, 466.1625 [calculated M + H]+.

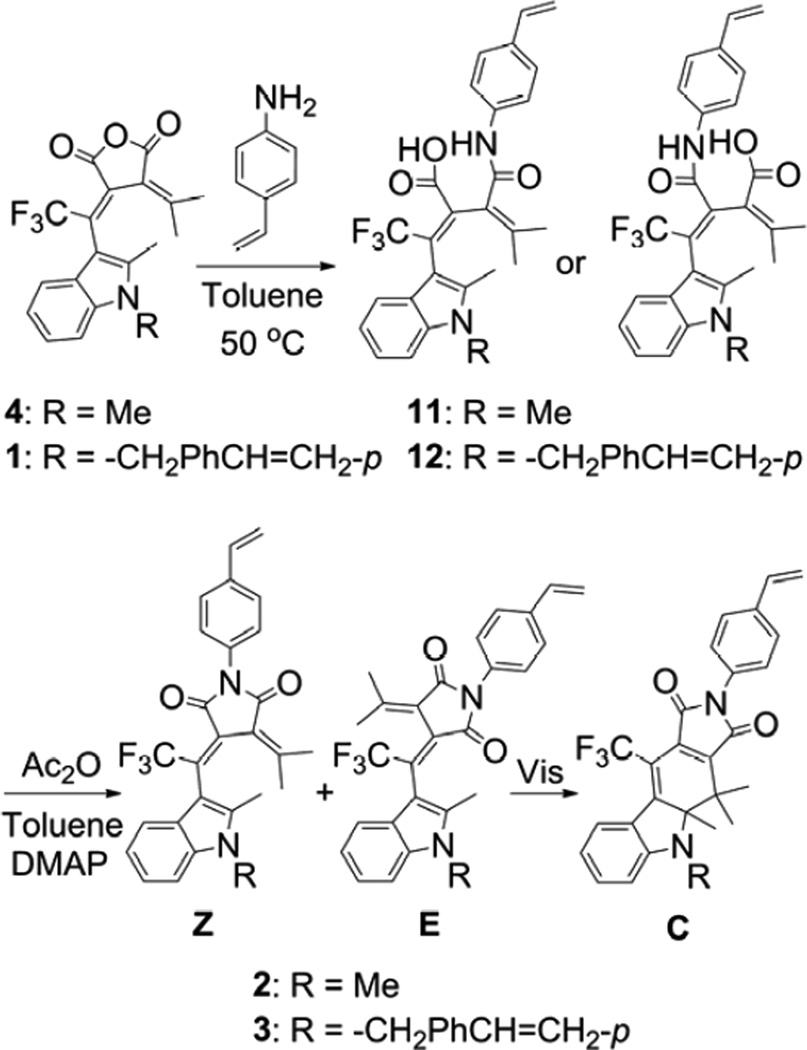

2.2.2. Synthesis of fulgimide 2 (Scheme 4)

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of fulgimides 2 and 3.

4-Vinylaniline (0.70 g, 5.9 mmol) was added to the Z-form solution of trifluoromethyl indolylfulgide (4) (1.50 g, 4.13 mmol) in 250 mL of toluene at room temperature. The reaction mixture was heated to 50 °C and stirred for 2 h. The solution was then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was quenched with 100 mL of 1 M HCl and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with H2O (100 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to provide the crude acid intermediate. Acetic anhydride (100 mL) was added to the crude acid intermediate in 125 mL of toluene. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 10 min and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (10 mg) was added. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo after 40 min. The residue was dissolved in 250 mL of EtOAc and extracted with saturated NaHCO3 (2 × 100 mL) and H2O (100 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The orange residue was purified by column chromatography with toluene. The resulting E/Z mixture was dissolved in 100 mL of toluene and illuminated with 405 nm light until PSS was reached, and then illuminated with visible light >515 nm to obtain crude Z-form solution. Toluene was removed in vacuo, and recrystallization from CH2Cl2/hexanes provided 0.54 g (28% from fulgide) of the Z-form vinyl trifluoromethyl indolylfulgimide (2). Z-form: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.53 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (td, J = 7.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (td, J = 7.5, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 17.6, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.16 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 166.3, 164.1, 154.4, 137.7, 137.0, 136.9, 136.1, 132.6 (d, J = 2 Hz), 130.9, 129.3 (q, J = 35 Hz), 126.8, 126.6, 125.4, 122.6, 122.5 (q, J = 278 Hz), 122.0, 121.0, 119.6, 115.0, 109.2, 107.6 (d, J = 2 Hz), 30.0, 26.7, 22.4, 12.0. C27H23F3N2O2 HRMS (ESI) m/z: 465.1796 [obtained M + H]+, 465.1784 [calculated M + H]+. The C-form was obtained by irradiating pure Z-form solutions of 2 (0.13 g) with 405 nm light followed by purification via flash column chromatography with toluene and recrystallization from CH2Cl2/hexanes (0.04 g, 30% yield). C-form: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.76 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.40 – 7.36 (m, 3H), 6.80 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (dd, J = 17.6, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.29 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 2.95 (s, 3H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.30 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 168.2, 165.0, 160.0, 159.9, 139.3, 136.8, 136.1, 135.8 (q, J = 1 Hz), 135.1, 131.1, 128.6 (q, J = 7 Hz), 126.7, 126.1, 122.6 (q, J = 273 Hz), 119.6, 119.0, 114.7, 109.5, 106.2 (q, J = 37 Hz), 75.9, 39.3, 32.6, 19.7, 19.1, 14.8. C27H23F3N2O2 HRMS (ESI) m/z: 465.1799 [obtained M + H]+, 465.1784 [calculated M + H]+.

2.2.3. Synthesis of fulgimide 3 (Scheme 4)

4-Vinylaniline (0.10 g, 0.84 mmol) was added to vinyl trifluoromethyl indolylfulgide 1Z (0.30 g, 0.65 mmol) in 60 mL of toluene at room temperature. The reaction mixture was heated to 50 °C and stirred for 2 h. The solution was then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was quenched with 100 mL of 1 M HCl and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 75 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with 50 mL H2O. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to provide the crude acid intermediate. Acetic anhydride (75 mL) was added to the crude acid intermediate in 100 mL of toluene. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 10 min and DMAP (4 mg) was added. After 30 min, the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in 150 mL of EtOAc and extracted with saturated NaHCO3 (3 × 50 mL) and H2O (75 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The orange residue was dissolved in 125 mL of toluene and illuminated with 405 nm light until the PSS was reached, and then the C-form was purified by column chromatography with toluene. Recrystallization from CH2Cl2/hexanes provided 0.11 g (30% from fulgide) of the C-form divinyl trifluoromethyl indolylfulgimide (3). C-form: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.32 – 7.27 (m, 3H), 6.88 (td, J = 7.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (dd, J = 17.8, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (dd, J = 17.7, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (d, J = 17.8 Hz, 1H), 5.29 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.27 (d, J = 10.9 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 4.15 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 1.64 (s, 3H), 1.49 (s, 3H), 1.32 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 167.9, 165.0, 160.4, 159.6 (q, J = 4 Hz), 140.5, 136.9, 136.8, 136.7, 136.3, 136.0, 135.6 (q, J = 1 Hz), 135.1, 130.1, 128.5 (q, J = 7 Hz), 126.8, 126.7, 126.6, 126.1, 122.6 (q, J = 273 Hz), 119.9, 114.7, 114.0, 110.6, 106.8 (q, J = 37 Hz), 77.04, 51.1, 39.3, 20.1, 18.6, 15.8. C35H29F3N2O2 HRMS (ESI) m/z: 589.2094 [obtained M + Na]+, 589.2073 [calculated M + Na]+. The Z-form was prepared by illuminating the C-form in CDCl3 with visible light >515 nm to quantitatively convert it to the Z-form. Z-form: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.52 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.46 – 7.38 (m, 3H), 7.36 – 7.28 (m, 3H), 7.24 – 7.15 (m, J = 6.4, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.75 (dd, J = 17.6, 11.0 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (dd, J = 17.5, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.37 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.26 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 5.25 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 166.2, 163.9, 154.5, 137.7, 137.3, 136.7, 136.6, 136.2, 136.1, 136.0, 133.1 (q, J = 2 Hz), 130.9, 129.3 (q, J = 35 Hz), 126.8, 126.7, 126.6, 126.4, 125.7, 122.6, 122.5 (q, J = 278 Hz), 122.4, 121.2, 119.8, 115.0, 114.5, 109.6, 108.4 (q, J = 2 Hz), 46.9, 26.9, 22.3, 12.1. C35H29F3N2O2 HRMS (ESI) m/z: 589.2097 [obtained M + Na]+, 589.2073 [calculated M + Na]+.

2.3. Linear copolymers 1-co-PMMA and 2-co-PMMA (Scheme 5)

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of the Z-form copolymers.

2.3.1. Synthesis

Free-radical solution addition polymerization technique was used. The monomer, fulgide 1 or fulgimide 2 (Z- or C-form), (4.6 mg, 0.01 mmol)) was dissolved in 2 mL of THF. Methyl methacrylate (0.40 g, 4 mmol) was added to the solution followed by the addition of initiator AIBN (1 wt% of MMA). The glass ampoule was sealed under vacuum and kept at 50 °C for 48 h. The ampoule was cooled to room temperature and 2 mL of hexane was added. The copolymer was precipitated and filtered. Molecular weights (g/mol): 1Z-co-PMMA Mn = 6.4 × 104, 1C-co-PMMA Mn = 6.0 × 104; 2Z-co-PMMA Mn = 5.9 × 104, 2C-co-PMMA Mn = 6.6 × 104.

2.3.2. Preparation of copolymer films

The copolymer (1Z/C-co-PMMA or 2Z/C-co-PMMA) (30 – 50 mg) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1 mL), and the solution was deposited via a pipet onto a circular glass slide (Escoproducts) and allowed to spread over the surface of the slide. The sample was allowed to dry overnight inside a glass Petri dish at room temperature. The resulting films were used to study the photochromic properties.

2.4. Synthesis of cross-linked copolymer 3-co-PMMA (Scheme 5)

To the solution of monomer 3 (Z- or C-form) (1.0 mg, 0.002 mmol) in methyl methacrylate (1.0 g, 10 mmol), AIBN (1 wt% of MMA) was added. The polymerization of this solution was performed between two 1 inch diameter circular glass slides with a 2 mm plastic spacer at 50 °C for 12 h. The resulting rigid thin films containing cross-linked copolymers were cooled to room temperature and directly utilized to investigate their stability.

2.5. Spectra determination in toluene

1Z, 2Z (general procedure): From a concentrated stock solution, 5 solutions with concentrations between 0.05 to 0.20 mM were obtained by dilution with toluene. UV-Vis spectra of these solutions were acquired. Concentrations versus absorbencies were plotted, and absorption coefficient at λmax was determined. For each compound, measurements were repeated 3 times.

1C, 2C: A concentrated stock solution was diluted to 5 solutions of different unknown concentrations, and their UV-Vis spectra were obtained. Each of the five C-form solutions was then quantitatively converted to a Z-form solution by illumination with 515 nm light and the UV-Vis spectrum was measured. Using the predetermined Z-form extinction coefficient, concentrations of the Z-form solutions, which are equivalent to the initial C-form solutions, were obtained and plotted versus the C-form absorbencies at λmax thus allowing the determination of the extinction coefficient for the C-form.

3C, 3Z: A concentrated stock solution of the C-form was prepared using 10 mg of solid sample followed by the preparation of 5 dilute solutions. UV-Vis spectra of these solutions were obtained, and then the extinction coefficient was determined. To obtain the extinction coefficient for the Z-form, these diluted C-form solutions, after their UV-Vis spectra were scanned, were irradiated with 515 nm light to quantitatively convert them to Z-form solutions. UV-Vis spectrum of each freshly converted Z-form solution was measured. The extinction coefficient was determined using the previously obtained extinction coefficient of 3C.

2.6. PSS measurements

The photostationary state (PSS) was measured using NMR spectroscopy. An NMR tube containing Z-form of fulgide (or fulgimide) in toluene-d8 was illuminated with 436 nm light (or 405 nm for fulgimides) until PSS was reached. A 1H NMR spectrum was then acquired and integrated.

2.7. Photochemical stability

For each compound, Z-form sample (solutions or films) was prepared with an initial absorbance of 0.6 – 0.8 at the absorption maxima. Sample was irradiated to PSS and an UV-Vis spectrum was acquired after prolonged irradiation at 436 nm for fulgide (PSS436nm) or 405 nm for fulgimides (PSS405nm). Then, another sample of pure Z-form was irradiated to 90% of the PSS, and the reaction time (coloration) was obtained. The 90% PSS mixture was then back irradiated to the yellow form, and again the reaction time (decolorization) was obtained. Absorbance of the C-form at λmax was < 0.01 upon decolorization. Once the duration of irradiation reactions (coloration – decolorization) was established, the system was automated through the use of a filter switch. After a designated number of irradiation cycles, the sample was fully converted to PSS and UV-Vis spectrum scanned. The photochemical fatigue was determined by comparison with the initial PSS absorption spectrum. The cycling times in toluene were: 40 s (Z – C) and 30 s (C – Z) for 1, 70 s (Z – C) and 60 s (C – Z) for 1-co-PMMA; 60 s (Z – C) and 40 s (C – Z) for 2, 3, and 2-co-PMMA; as films: 300 s (Z – C) and 180 s (C – Z) for 1-co-PMMA, 150 s (Z – C) and 60 s (C – Z) for 2-co-PMMA, 80 s (Z – C) and 90 s (C – Z) for 3-co-PMMA.

2.8. Thermal stability

Polymer-based study: Thin films of 1-co-PMMA, 2-co-PMMA, and 3-co-PMMA (Z- and C-forms) were wrapped in aluminum foil and placed in an oven maintained at 80 °C. The films were removed at prescribed intervals and their UV-Vis spectra measured.

Solution-based study: The thermal stability of fulgide 1, fulgimides 2 and 3 and copolymers 1-co-PMMA and 2-co-PMMA (Z- and C-forms) in toluene was measured using UV-Vis spectroscopy. Thermal stability of monomers 1, 2, and 3 was also followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The solutions were prepared in toluene or its deuterated analog and then transferred into several ampoules or NMR tubes, respectively. UV-Vis and 1H NMR spectra of these initial samples were then acquired. Ampoules and NMR tubes were sealed and submersed in a water bath maintained at 80 °C. At predetermined times, ampoules and NMR tubes were removed, and their contents analyzed by UV-Vis or 1H NMR spectroscopy.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Synthesis

Three photochromic copolymers containing photochromic 3-indolylfulgides and 3-indolylfulgimides were synthesized and studied. Copolymers were prepared in both the open and the closed forms of the indolylfulgides and indolylfulgimides. To prepare the copolymers, a number of precursors were synthesized. A fulgide, containing a polymerizable styrene group, 2-methyl-1-(4-vinylbenzyl)-3-trifluoromethyl indolylfulgide 1, was prepared by a Stobbe condensation of the corresponding indole-3-carboxaldehyde 7 with a substituted methylene succinate 8, followed by hydrolysis and dehydration (Scheme 3) [1,17,34]. Trifluoromethyl indolylfulgide 4 was synthesized as reported previously [34,35]. Fulgimides 2 and 3 were synthesized from the corresponding fulgides in two steps. The first step involved reaction of fulgide, 4 or 1, with 4-vinylaniline in toluene and provided an acid intermediate, 11 or 12; the second step was subsequent dehydration of the acid intermediate with acetic anhydride (Scheme 4). The copolymers, 1-co-PMMA, 2-co-PMMA, and 3-co-PMMA, were prepared using a free-radical solution addition polymerization technique in the presence of AIBN as initiator (Scheme 5, shown for the Z-forms). The ratios of monomers (photochromic molecule to MMA) were selected to ensure that the copolymers were suitable for UV-vis measurements (absorbance approx. 1). Copolymer films 1-co-PMMA and 2-co-PMMA were prepared using drop casting, and the cross-linked copolymer 3-co-PMMA was obtained by polymerization between two glass slides. All copolymers were found to be photochromic and stable (in both forms) at room temperature, and their photochromic properties were studied in toluene (1-co-PMMA, 2-co-PMMA, only) and as thin films. The cross-linked copolymer of fulgimide 3 with MMA, 3-co-PMMA, was found to be insoluble in THF, DCE, CH2Cl2, or toluene and very rigid, optically clear, and difficult to break.

3.2. UV-vis absorption spectra

For a given photochromic compound, the polymerization state did not affect the absorbance maxima, however the substitution pattern around the indole ring did. The UV-vis absorption spectra of 1, 2, and 3 were measured in toluene (Fig. 1) as toluene is the standard solvent for studying indolylfulgides/fulgimides (Table 1) [4–7,36]. Monomers and polymers of 3-indolylfulgides/fulgimides have very similar absorption maxima, as was the case for 2-indolylfulgide/fulgimides [17]. The substitution of a styrene group (1 or 3) for a methyl group (4 or 2) on the nitrogen of the indole does not change significantly the absorbance maximum or extinction coefficient of the open Z-form, but a hypsochromic shift of approx. 20 nm in the absorbance maximum is observed for the closed C-form. As expected, the absorbance maxima of the Z-form of fulgides were red shifted by approx. 20 nm relative to the corresponding fulgimides, e.g. 1Z versus 2Z and 3Z [1,17]. The photostationary state (PSS) – C:Z:E ratio – reached upon irradiation with 436 nm light for fulgide and 405 nm light for fulgimides – was shown to contain greater than 93% C-form (Table 1). Advantageous properties of 1, 2, and 3 include the absorption maxima in the visible region of the spectrum for all forms and high conversion in both directions that makes the compounds practical for many applications.

Fig. 1.

UV-Vis absorption spectra of fulgide 1 (solid), and fulgimides 2 (dashed) and 3 (dotted) in toluene.

Table 1.

Extinction coefficients at λmax for 1, 2, and 3 in toluene and λmax for their copolymers in toluene and as thin films.

| Compound (Medium) | λmax/nm (εmax/mol−1 L cm−1) | PSS436 nm (405 nm)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-form | C-form | C:Z:E | |

| 1 (Toluene) | 424 (5.5 × 103) | 549 (7.3 × 103) | 94:5:1 |

| 2 (Toluene) | 405 (6.4 × 103) | 554 (7.4 × 103) | 93:4:3 |

| 3 (Toluene) | 401 (6.3 × 103) | 537 (8.1 × 103) | 95:4:1 |

| 4b (Toluene) | 427 (5.8 × 103) | 571 (7.0 × 103) | 95:3:2 |

| 1-co-PMMA (Toluene) | 424 | 550 | - |

| 2-co-PMMA (Toluene) | 405 | 554 | - |

| 1-co-PMMA (Film) | 425 | 554 | - |

| 2-co-PMMA (Film) | 405 | 557 | - |

| 3-co-PMMA (Film) | 402 | 540 | - |

Photostationary state.

The data taken from ref. 4.

3.3. Thermal stability

In all cases, the C-forms were more stable than the Z-forms at 80 °C which is common for fluorinated indolyfulgides/indolylfulgimides [4]. Thermal stability at 80 °C was examined by UV-vis spectroscopy. 1H NMR spectroscopy was also used in the case of monomers 1, 2, and 3. These conditions were selected in order to compare the results with previous studies [4,5,7,36]. The C-form data were fit to a single exponential decay excluding the first data point (Table 2) as there is an initial 1–2% loss in the absorbanse followed by a slow decomposition. The decomposition products were assumed not to absorb at the λmax of the C-form. In all cases, the C-forms were very stable and decomposed less than 14% after 400 h at 80 °C. The C-form monomers were more stable than the corresponding copolymers. The decomposition of monomers was 3% or less after 400 h.

Table 2.

Thermal decomposition rate constants (×103, h−1) and photochemical fatigue resistance for 1, 2, and 3 and their copolymers at 80 °C.

| Compound | Medium | UV-Vis | 1H NMR | Photochemical decomposition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-forma | C-formb | Z-formc | C-formb | Cycles | A/A0 | % per cycle | ||

| 1 | Toluene | 53d | < 0.05 | 20 | < 0.05 | 2760 | 0.809 | 0.0050 |

| 2 | Toluene | 18c | < 0.05 | 14 | < 0.05 | 1660 | 0.738 | 0.016 |

| 3 | Toluene | 18c | < 0.05 | 11 | < 0.05 | 2990 | 0.848 | 0.0050 |

| 1-co-PMMA | Toluene | 105d | 0.19 | 1898 | 0.791 | 0.012 | ||

| 2-co-PMMA | Toluene | 88d | 0.21 | 1674 | 0.738 | 0.014 | ||

| 1-co-PMMA | Film | 543d | 0.15 | - | 760 | 0.794 | 0.030 | |

| 2-co-PMMA | Film | 32c | 0.16 | 1014 | 0.794 | 0.017 | ||

| 3-co-PMMA | Film | 16c | 0.37 | 2378 | 0.793 | 0.005e | ||

The first 200 h data were fit only.

Fit to a single exponential excluding 0 h data point.

Fit to a single exponential.

Fit to a sequential decay.

From 500 cycles onwards.

For Z-form monomers in toluene at 80 °C, the UV-vis spectra were characterized by an initial drop in absorbance followed by a bathochromic shift and subsequent increase in absorbance and the absence of the isobestic points (indicating the presence of an intermediate) (e.g. Fig. 2). This pattern is similar to that observed for fulgide 4Z. Fulgide 4Z decomposes via a 1,5-hydrogen shift from the isopropylidene group to form an intermediate which then rearranges to a mixture of two products [35]. Concurrently, reversible 4Z-to-4E isomerisation also takes place. The decomposition rate constants for the single exponential decay of 1Z, 2Z, and 3Z obtained by 1H NMR spectroscopy were similar to that observed for 4Z (0.023 h−1) [4,34]. According to the 1H NMR data, no polymerization of 1, 2, or 3 occurred during thermolysis. The Z-form UV-vis data were fit to a single exponential decay or a sequential decomposition pathway, A → B → C, with the rate constants for A → B being reported (Table 2) and gave analogous results to the 1H NMR spectroscopy data.

Fig. 2.

Thermal decomposition of fulgimide 3Z in toluene by UV-Vis at 80 °C.

For Z-form copolymers in toluene and as films, the UV-Vis spectra with time at 80 °C displayed a similar pattern as the corresponding monomers (Fig. 3 and 4). However, at longer times (> 100 – 200 h) the absorbance of the red shifted peak decreased, potentially indicating decomposition of a thermolysis product(s). Thus, the data was only fit for the first 200 h (Table 2). As was the case for the C-forms, the Z-form monomers were, in general, more stable than the corresponding copolymers.

Fig. 3.

Thermal decomposition of copolymer 2Z-co-PMMA and 3Z-co-PMMA at 80 °C by UV-Vis.

Fig. 4.

Thermal decomposition of copolymers as films at 80 °C: 1Z-co-PMMA (■), 2Z-co-PMMA (●), 3Z-co-PMMA (♦), 1C-co-PMMA (□), 2C-co-PMMA (○), and 3C-co-PMMA (◊).

As films, all copolymers revealed good stability at room temperature in both the Z- and C-forms (no loss of absorption within experimental error after 5 weeks). In an earlier report, 2-indolylfulgides and fulgimides, which were copolymerized with MMA, were found to be stable at room temperature as well [17] Ultimately, the thermal stability of fluorinated indolylfulgides/indolylfulgimides is limited by the least stable Z-form in either toluene or as thin films.

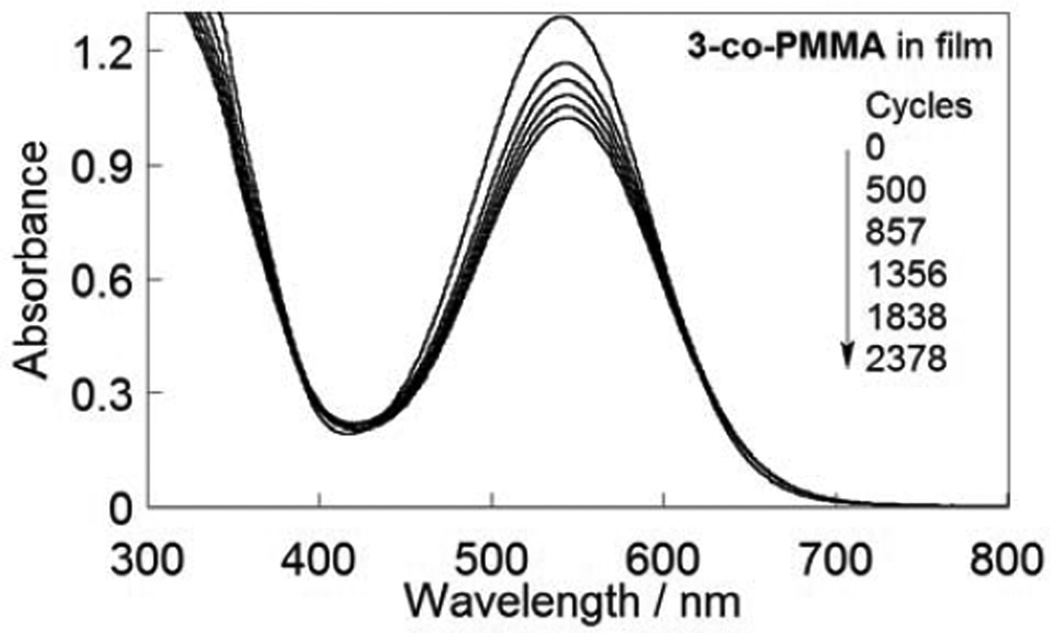

3.4. Photochemical stability

For fulgimides 2 and 3, but not fulgide 1, the polymerization state did not affect the fatigue resistance, however the substitution pattern around the indole ring did (Table 2). Photochemical stability (fatigue resistance) is defined here as the percentage loss in absorbance per photochemical cycle (ring-opening/ring-closing) during approx. the first 20% of degradation. Fulgide 1 and fulgimides 2 and 3 were found to be photochromic, and copolymers based on these compounds remained photochromic as well. On average, 3-indolylfulgimides, monomers or polymers in toluene or as films, degraded less than 3% per 100 cycles while copolymers composed of 2-indolylfulgimide and MMA degraded less than 10% after 100 photochromic cycles [17]. In toluene, fulgide 1 and its derivative 3 (Fig. 5 and 6) showed good stability, degrading 0.005% per cycle, which is comparable with fulgide 4 (3000 times before degrading by 21%, 0.007% per cycle) [5]. Fulgimide 2 showed slightly less photochemical stability (Table 2). With cross-linked copolymer 3-co-PMMA as a film, there was an initial drop in absorbance followed by a linear decomposition, possibly because of polymer reorganization (Fig. 6). The change in stability with polymerization state for fulgide 1 might be due to longer cycling times. As we went from 1 in toluene to 1-co-PMMA in toluene to 1-co-PMMA as a film, the Z to C conversion time went from 40 to 70 to 300 s while C to Z conversion time went from 35 to 60 to 180 s. Although, the conversion times also increased for fulgimides 2 and 3, the change was less dramatic: in toluene versus polymer film, they were Z to C 60 vs 150 s (2) and 60 vs 80 s (3) and C to Z 40 vs 60 s (2) and 40 vs 90 s (3). As a control, 1-co-PMMA as a film was prepared in the same way as 3-co-PMMA as a film, but the conversion times did not change. Typical errors for the photochemical stability experiments were 10% in toluene and 20% in film.

Fig. 5.

PSS absorbance of copolymer 3-co-PMMA as a film after indicated number of cycles.

Fig. 6.

Photochemical decomposition of 1 (■), 2 (●), and 3 (♦) in toluene; 1-co-PMMA (□), 2-co-PMMA (○), and 3-co-PMMA (◊) as films. For all data, a linear fit applied, but the initial point for 3-co-PMMA was not included due to an initial drop.

3.5. Conformational restrictions

In films, the initial form, open or closed, of the fulgide or fulgimides affected the percent conversion of the open form to the closed form. When copolymer films initially prepared in the open Z-form were converted to PSS436/405 nm, the absorbance at λmax decreased (e.g. Fig. 7a). However, when copolymer films prepared in the C-form were converted to the open Z-form and then converted to PSS436/405 nm, the absorbance at λmax increased or decreased slightly (e.g. Fig. 7b). Although, the effect was more pronounced for the cross-linked copolymer 3-co-PMMA (Fig. 7), the effect was also observed for the linear copolymers films 1-co-PMMA and 2-co-PMMA. Control experiments with 2-co-PMMA were performed. Z-form copolymer 2-co-PMMA prepared from C-form copolymer in solution and then deposited as a film, showed greater decrease in absorbance than film prepared directly from the C-form 2-co-PMMA. In solution, the effect was absent, the same change in relative absorbance was observed starting from either Z-form or C-form 2-co-PMMA.

Fig. 7.

Cycling of 3-co-PMMA starting from Z-form (a) and C-form (b).

Diarylethenes also display the same behavior in films because conversion from the parallel to antiparallel conformation required for ring-closing is restricted by the matrix [33]. Starting from the open form, a mixture of parallel and antiparallel conformations that interchange slowly, if at all, in films is produced, but only the antiparallel conformation can be converted to the closed form. However, when the open form is produced in situ from the closed form, the open form is obtained in the reactive antiparallel conformation but not the unreactive parallel conformation. As a result, it is recommended that polymer films of diarylethenes be prepared in the closed forms.

Given the similarities in results for diarylethenes and fulgides/fulgimides containing polymers, we propose that restrictive rotation within the matrix is responsible for the lower conversion of the open to closed form starting from polymer films prepared in the open form. The indole ring of 3-indolylfulgides is known to adopt two different conformations in crystal structures, only one of which places the atoms in the correct position to cyclize and produce the closed form (Scheme 6) [37]. Although, the effect is less for indolylfulgides/indolylfulgimides than for diarylethenes, it is still significant. The smaller effect is most likely due to different ratios of reactive to unreactive conformations in the polymer film. In addition, there was no indication of interconversion between the open conformations of the indolylfulgimides in the cross-linked copolymer 3-co-PMMA on the time scale of days.

Scheme 6.

Conformations of fulgide.

4. Conclusions

We have synthesized 3-indolylfulgide and 3-indolylfulgimides with pendant styrene group(s) and copolymerized them with MMA to obtain linear and cross-linked copolymers (in the Z- and C-forms). All copolymers (in the Z- or C-forms) were found to be photochromic and very stable at room temperature, absorbing light in the visible region of the spectrum. At 80 °C, in toluene or as films, the copolymers showed the same trends as the corresponding fluorinated 3-indolylfulgide/fulgimides monomers: the Z-forms were less stable than the C-forms, decomposing through intermediates, while the C-form copolymers were very stable – little or no decomposition after 400 h. The new compounds were also tested for ability to convert between the open and closed forms. Copolymers degraded less than 3% per 100 cycles in toluene or as films similar to monomers. For the copolymers, cycling times were longer as films than in solution. Ultimately, copolymers in solution and as films maintained all the advantageous properties of the monomers. However, in films, the open Z-form was conformationally restricted indicating that it is preferential to prepare films in the closed C-form.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NIH/NIGMS program (SC3GM084752) and a Dissertation Year Fellowship to X.C. (Florida International University, Graduate School) are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fan M-G, Yu L, Zhao W. In: Organic Photochromic and Thermochromic Compounds. Crano JC, Guglielmetti RJ, editors. vol. 1. New York: Plenum Press; 1999. pp. 140–206. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokoyama Y. Fulgides for memories and switches. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1717–1739. doi: 10.1021/cr980070c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yokoyama Y, Takahashi K. Trifluoromethyl-substituted photochromic indolylfulgide. A remarkably durable fulgide towards photochemical and thermal treatments. Chem Lett. 1996;12:1037–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islamova NI, Chen X, Garcia SP, Guez G, Silva Y, Lees WJ. Improving the stability of photochromic fluorinated indolylfulgides. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2008;195:228–234. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolak MA, Gillespie NB, Thomas CJ, Birge RR, Lees WJ. Optical properties of photochromic fluorinated indolylfulgides. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2001;144:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolak MA, Thomas CJ, Gillespie NB, Birge RR, Lees WJ. Tuning the optical properties of fluorinated indolylfulgimides. J Org Chem. 2003;68:319–326. doi: 10.1021/jo026374n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Islamova NI, Garcia SP, DiGirolamo JA, Lees WJ. Synthesis and optical properties of aqueous soluble indolylfulgimides. J Org Chem. 2009;74:6777–6783. doi: 10.1021/jo900909d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irie M. In: Molecular Switches. Feringa BL, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2001. pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokoyama Y. In: Molecular Switches. Feringa BL, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2001. pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feringa BL, van Delden RA, Koumura N, Geertsema EM. Chiroptical molecular switches. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1789–1816. doi: 10.1021/cr9900228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irie M. Diarylethenes for memories and switches. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1685–1716. doi: 10.1021/cr980069d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willner I, Rubin S. Control of the structure and functions of biomaterials by light. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:367–385. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berns MW, Krasieva T, Sun C-H, Dvornikov A, Rentzepis PM. A polarity dependent fluorescence "switch" in live cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2004;75:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straight SD, Terazono Y, Kodis G, Moore TA, Moore AL, Gust D. Photoswitchable sensitization of porphyrin excited states. Aust J Chem. 2006;59:170–174. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beharry AA, Woolley GA. Azobenzene photoswitches for biomolecules. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4422–4437. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15023e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yager KG, Barrett CJ. Novel photo-switching using azobenzenes functional materials. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2006;182:250–261. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang Y, Dvornikov AS, Rentzepis PM. Synthesis and properties of photochromic fluorescing 2-indolyl fulgide and fulgimide copolymers. Macromolecules. 2002;35:9377–9382. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang Y, Dvornikov AS, Rentzepis PM. Photochromic cross-linked copolymer containing thermally stable fluorescing 2-indolylfulgimide. Chem Commun. 2000:1641–1642. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen J, Huang J, Luo Y, Zhang Q, Wang K. Photo-induced alignment behavior of azobenzenes-containing polymer films with different cross-linking degree. Chin J Chem Phys. 2008;21:493–499. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ercole F, Davis TP, Evans RA. Photo-responsive systems and biomaterials: photochromic polymers, light-triggered self-assembly, surface modification, fluorescence modulation and beyond. Polym Chem. 2010;1:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irie M. Photoresponsive polymers. Adv Polym Sci. 1990;94:27–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Q, Cheng H, Tian H. Recent progress on photochromic diarylethenes polymers. Polym Chem. 2011;2:2435–2443. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belfield KD, Liu Y, Negres RA, Fan M, Pan G, Hagan DJ, Hernandez FE. Two-photon photochromism of an organic material for holographic recording. Chem Mater. 2002;14:3663–3667. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willner I, Rubin S. Reversible photoregulation of the activities of proteins. React Polym. 1993;21:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willner I. Photoswitchable biomaterials: en route to optobioelectronic systems. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willner I, Rubin S, Zor T. Photoregulation of α-chymotrypsin by its immobilization in a photochromic azobenzene copolymer. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4013–4014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willner I, Rubin S, Shatzmiller R, Zor T. Reversible light-stimulated activation and deactivation of α-chymotrypsin by its immobilization in photoisomerizable copolymers. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8690–8694. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimoboji T, Larenas E, Fowler T, Kulkarni S, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. Photoresponsive polymer-enzyme switches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16592–16596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262427799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar GS, Savariar CS, Saffran M, Neckers DC. Chelating copolymers containing photosensitive functionalities. 3. Photochromism of cross-linked polymers. Macromolecules. 1985;18:1525–1530. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciardelli F, Pieroni O. In: Molecular Switches. Feringa BL, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2001. pp. 399–441. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nithyanandan S, Kannan P, Kumar KS, Ramamurthy P. Optical switching, photophysical, and electrochemical behaviors of pendant triazole-linked indolylfulgimide polymer. J Polym Sci Part A Polym Chem. 2011;49:1138–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saravanan C, Kannan P. Dual-mode optical switching property of copolymers containing pendant nitro and cyano substituted azobenzenes and fulgimides units. Polym Degrad Stab. 2009;94:1001–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wigglesworth TJ, Myles AJ, Branda NR. High-content photochromic polymers based on dithienylethenes. Eur J Org Chem. 2005:1233–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolak MA, Sullivan JM, Thomas CJ, Finn RC, Birge RR, Lees WJ. Thermolysis of a fluorinated indolylfulgide features a novel 1,5-indolyl shift. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4739–4741. doi: 10.1021/jo015693w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas CJ, Wolak MA, Birge RR, Lees WJ. Improved synthesis of indolyl fulgides. J Org Chem. 2001;66:1914–1918. doi: 10.1021/jo005722n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Islamova NI, Chen X, DiGirolamo JA, Silva Y, Lees WJ. Thermal stability and photochromic properties of a fluorinated indolylfulgimide in a protic and aprotic solvent. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2008;199:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolak MA, Finn RC, Rarig RS, Jr, Thomas CJ, Hammond RP, Birge RR, Zubieta J, Lees WJ. Comparing structural properties of a series of photochromic fluorinated indolylfulgides. Acta Cryst. 2002;C58:o389–o393. doi: 10.1107/s0108270102008041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]