Abstract

Findings from experimental studies and animal models led to the hypothesis that folic acid supplementation during pregnancy confers an increased risk of asthma. This review provides a critical examination of current experimental and epidemiologic evidence of a causal association between folate status and asthma. In industrialized nations, the prevalence of asthma was rising before widespread fortification of foodstuffs with folic acid or folate supplementation before or during pregnancy, thus suggesting that changes in folate status are an unlikely explanation for “the asthma epidemic.” Consistent with this ecologic observation, evidence from human studies does not support moderate or strong effects of folate status on asthma. Given known protective effects against neural tube and cardiac defects, there is no reason to alter current recommendations for folic acid supplementation during conception or pregnancy based on findings for folate and asthma. Although we believe that there are inadequate data to exclude a weak effect of maternal folate status on asthma or asthma symptoms, such effects could be examined within the context of very large (and ongoing) birth cohort studies. At this time, there is no justification for funding new studies of folate and asthma.

Keywords: folate, asthma, asthma morbidity

In 2010, approximately 25.7 million people had asthma in the United States (1). Changes in the intake of certain nutrients or dietary patterns could partly explain this “asthma epidemic” in the United States and other industrialized countries (2–4).

Dietary changes could affect asthma through epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation, which may lead to heritable or postnatal changes in gene expression without alterations in DNA sequence (5). For example, maternal levels of folate (a methyl donor) could alter the risk of asthma by causing hypo- or hypermethylation (and thus increased or decreased expression) of disease-susceptibility genes in relevant fetal tissues (6, 7).

Findings in a mouse model suggest that maternal dietary intake of methyl donors modifies risk of allergic airways disease (AAD) (8) and has generated considerable interest in a potential link between folate and asthma in humans. In this review, we critically assess existing evidence for a causal association between folate status and asthma or atopy and suggest future directions for research in this field.

Folate Metabolism and Physiology

Folic acid is a synthetic form of folate used in fortification of foodstuffs and nutritional supplements, and folate is a generic term referring to all derivatives of folic acid.

Dietary folates are polyglutamates that are absorbed in the proximal small intestine after hydrolysis. The bioavailability of dietary folates is approximately one-half that of folic acid (a monoglutamate) (9). Establishing precise dietary folate equivalents (DFEs) that account for differences in bioequivalence between folic acid and dietary folates is challenging (10).

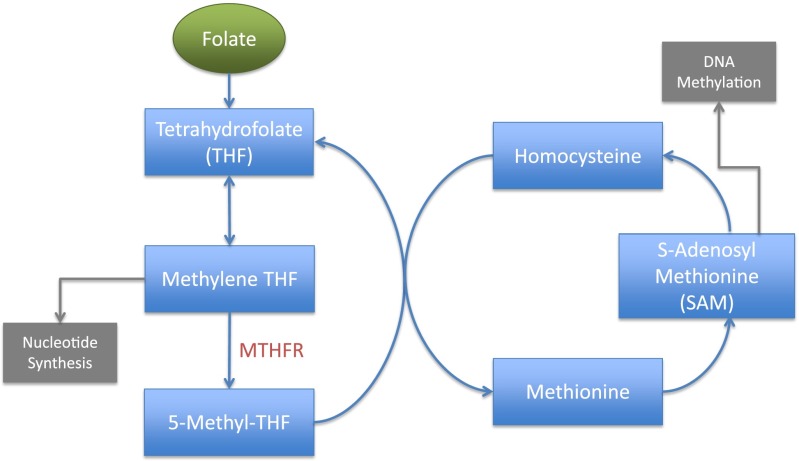

Folate is critical in the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, amino acids, and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). SAM, a key methyl donor in many biochemical reactions, has a role in the methylation of phospholipids, RNA, and DNA (11). Folate metabolism (Figure 1) generates numerous essential and nonessential amino acids.

Figure 1.

Folate metabolism. Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the regeneration of methyl donors. Methylene tetrahydrofolate (THF) has a role in nucleotide synthesis, and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) contributes to DNA methylation.

The tetrahydrofolate (THF) molecule is a primary folate acceptor. THF is converted to methylene-THF, both directly and via formylated folate. Once methylene-THF is converted to 5-methyl-THF by methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), the methyl group that originated with folate is transferred to homocysteine. This process of methyl transfer results in the generation of methionine (12), which, in turn, helps to regenerate SAM.

Assessment of Folate Status

Folate is accumulated in red blood cells (RBCs) during erythropoiesis. The three primary folate species (vitamers) in serum are 5-methyl-THF, 5-formyl-THF, and folic acid. Although all vitamers mediate some of the varied biological effects of folate, usual biomarkers or dietary assessment tools estimate only “global” folate status.

Commonly used biomarkers include RBCs and serum folate. Although RBC analysis indicates folate status over approximately 3 months (13), serum folate reflects short-term intake of this nutrient. Dietary assessment tools, aiming to capture “usual intake” of folate, include: multiple 24-hour dietary recalls, food diaries, and food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) (14). Accurate estimation of folate intake by self-report (e.g., by FFQs) is difficult due not only to high day-to-day variation in diet but also to systematic over- or underestimation of intake (15, 16) and random measurement error (17). Moreover, the relationship between self-reported intake and serum folate is not uniformly linear at all intake levels (18).

Animal Models of Folate Status and Asthma or Atopy

Animal models provide an excellent tool to better understand mechanisms that contribute to the fetal origins of airways diseases such as asthma. To our knowledge, there is no published animal model of the effects of exclusive folate intake on experimental asthma (AAD). However, previous work shows that enriching the diet of female mice with methyl donors (including, but not limited to, folic acid) during pregnancy impacts AAD (8). In this study, high maternal intake of methyl donors enhanced the severity of AAD (as indicated by increased airway responsiveness, serum total IgE, and eosinophils and IL-13 in lung lavage) in offspring (the F1 generation) of C57BL/6J mice. This trait was partially transmitted to the next (F2) generation. A diet rich in methyl donors during lactation or adulthood had no effect on AAD in this experimental model, suggesting that gestation is the period most vulnerable to dietary manipulation (8). Consistent with effects on lymphocyte maturation and development, a maternal diet rich in methyl donors led to an increased ratio of CD4+/CD8+ lymphocytes in the spleen of the offspring. In addition, this in utero dietary intervention led to increased production of IL-4 by splenic CD4+ cells stimulated with monoclonal antibodies to CD3+CD28+ cells, further suggesting that a maternal diet rich in methyl donors favors lymphocyte maturation into a Th2 phenotype (8).

To examine whether their findings were due to changes in DNA methylation of genes relevant to T lymphocyte regulation, genome-wide site-specific DNA methylation was assessed in lung tissue from F1 mice of the phenotypic extremes of AAD that were gestated on a maternal diet high or low in methyl donors (8). Using this genomic approach, 82 loci were found to be differentially methylated after a methyl donor–rich diet: these methylation changes were further shown to result in decreased transcriptional activity and increased severity of AAD. Runt-related transcription factor (Runx3, a gene implicated in negative regulation of AAD in mice) was shown to be hypermethylated, and Runx3-mRNA and protein levels were suppressed in F1 mice exposed to a maternal diet rich in methyl donors. Of interest, treatment of DNA from splenocytes with a demethylating agent led to increased transcription of Runx3 in mice previously exposed to a maternal diet rich in methyl donors (8). Although mouse models strongly support a role for DNA methylation in the regulation of allergic airway inflammation (19, 20), the specific role of dietary folate on the pathogenesis of AAD in mice, if any, is unknown.

Epidemiologic Studies of Folate Status and Asthma or Atopy

Findings in mouse models and/or known effects of methyl donors (including folate) on epigenetic marks (DNA methylation) have motivated 20 epidemiologic studies of folate and asthma or atopy (Tables 1 and 2). The discrepant results of these studies are likely due to differences in design (e.g., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal), sample size, age and selection of participants, phenotypic assessment of asthma or atopy, timing or methods (e.g., questionnaire assessment versus biomarkers) used for measurement of folate status, and analytical approach (e.g., adjustment for intake or level of other nutrients).

TABLE 1.

CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDIES OF FOLATE STATUS AND ASTHMA OR ATOPY

| Reference | Study Design | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thuesen et al. (15) |

Cross-sectional study of 6,784 Danish adults aged 30–60 yr |

Serum folate inversely associated with physician-diagnosed asthma but not with impaired lung function, airflow obstruction, or atopy |

Lack of data on nutritional supplements and limited assessment of dietary intake |

| Bueso et al. (16) |

Nested case-control study of 169 Norwegian children aged 13–14 yr |

No significant association between dietary folate intake (assessed by food diaries) and physician-diagnosed asthma |

Small sample size, lack of data from a food frequency questionnaire or folate levels, and potential selection bias |

| Matsui and Matsui (21) |

Cross-sectional study of 8,083 U.S. children and adults (aged 2–85 yr) |

Serum folate inversely associated with wheeze, total IgE, and atopy; no significant association with physician-diagnosed asthma |

Nonassessment of dietary intake and age heterogeneity of study participants |

| Farres et al. (22) |

Case-control study of 180 adults in Egypt |

No significant association between serum folate and asthma. Among subjects with asthma (n = 120), serum folate was inversely associated with total IgE |

Small sample size, nonassessment of dietary intake, and potential selection bias |

| Woods et al. (23) |

Cross-sectional study of 1,601 adults (aged 20–44 yr) in Australia |

Dietary intake of folate was significantly associated with physician-diagnosed asthma ever (adjusted odds ratio for each μg = 2.2, 95% confidence interval = 1.2–3.9) but not with current asthma, airway responsiveness, or atopy. |

Lack of folate levels, likely selection bias, and nonadjustment for multiple testing |

| Shaheen et al. (24) |

Case-control study of 40 Indian children aged 2–4 yr |

No significant association between serum folic acid and atopic dermatitis |

Small sample size, nonassessment of dietary intake, and potential selection bias |

| Patel et al. (25) | Nested and matched case-control study of 1,030 adults (aged 45–75 yr) in England | Dietary intake of folate was significantly associated with reduced odds of physician-diagnosed asthma | Nonassessment of folate supplementation or folate levels, potential selection bias, and lack of objective markers of asthma or atopy |

TABLE 2.

LONGITUDINAL STUDIES OF FOLATE STATUS AND ASTHMA

| Reference | Study Design | Main Findings | Study Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Okupa et al. (26) |

Prospective cohort study of 138 U.S. children followed from ages 2–9 yr |

Increased serum folate levels at or before age 6 yr were significantly associated with allergic sensitization but not with serum total IgE, asthma, or wheezing at ages 6 or 9 yr |

Small sample size, potential selection bias due to substantial loss of follow-up of original study participants, nonassessment of dietary intake, and limited adjustment for potential confounders |

| Lin et al. (27) |

Prospective study of 144 inner-city U.S. children with persistent asthma (aged 5–17 yr) followed for 1 yr |

Serum folate not significantly associated with fractional exhaled nitric oxide, degree of atopy, lung function, or hospitalizations for asthma. Compared with the first (but not the third or fourth) quartile, a folate level in the second quartile was significantly associated with increased total IgE |

Small sample size, nonassessment of dietary intake, lack of correction for multiple testing, and limited adjustment for potential confounders |

| Miyake et al. (28) |

Birth cohort study of 763 Japanese children followed up to age 16–24 mo |

No significant association between maternal folate intake at any trimester of pregnancy and wheeze or eczema at age 16–24 mo |

Nonassessment of folate supplementation or folate levels, lack of analysis of folate intake by trimester of pregnancy, no objective markers of asthma or atopy, potential selection bias, and short duration of follow-up |

| Litonjua et al. (29) |

Birth cohort study of 1,290 U.S. children followed up to age 2 yr |

No significant association between maternal folate intake in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy and wheeze or eczema at age 2 yr |

Lack of folate levels, no objective markers of atopy or asthma, and limited duration of follow-up |

| Håberg et al. (30) |

Birth cohort study of 32,077 Norwegian children followed up to age 18 mo |

Folic acid supplementation in the first trimester of pregnancy was significantly associated with increased risk of wheeze, LRIs, and hospitalizations at age 18 mo |

Maternal folate status assessed only by self-reported supplementation, lack of objective markers of atopy or asthma, short duration of follow-up (and thus inability to confidently diagnose asthma) |

| Nwaru et al. (31) |

Birth cohort study of 2,441 Finnish children at risk for diabetes mellitus type I, followed up to age 5 yr |

No significant association between maternal folate intake in the third trimester of pregnancy and asthma at age 5 yr |

Nonassessment of maternal folate intake in the first or second trimester of pregnancy, lack of folate levels, limited duration of follow-up, and potential selection bias |

| Whitrow et al. (32) |

Birth cohort study of 423 Australian children followed up to age 5.5 yr |

Maternal folic acid supplementation in late pregnancy was significantly associated with increased risk of asthma at 3.5 yr. Similar but nonsignificant findings were shown at age 5.5 yr |

Lack of folate levels, potential selection bias, no objective markers of asthma or atopy |

| Martinussen et al. (33) |

Birth cohort study of 1,499 U.S. children followed up to age 6 yr |

No significant association between maternal folate supplementation in the first trimester of pregnancy and asthma at age 6 yr |

Nonassessment of dietary intake or folate levels, potential selection bias, and lack of objective markers of asthma or atopy |

| Granell et al. (34) |

Birth cohort study of 5,364 British children followed up to age 7–8 yr |

No significant association between maternal folate intake in the third trimester of pregnancy and atopy (≥ 1 positive skin test to allergens) at age 7–8 yr |

Nonassessment of dietary intake in the first or second trimester of pregnancy, potential selection bias, lack of folate levels |

| Bekkers et al. (35) |

Birth cohort study of 3,786 Dutch children followed up to age 8 yr |

No overall (from 1–8 yr of age) significant association between folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and (frequent) asthma symptoms, wheeze, LRIs, or eczema. Negative findings also obtained for airway responsiveness or allergic sensitization at age 8 yr |

Lack of data on maternal dietary intake or folate levels, potential selection bias due to significant loss of follow-up (∼ 57%) at age 8 yr |

| Magdelijns et al. (36) |

Birth cohort study of 2,834 Dutch children followed up to age 7 yr |

No significant association between maternal folate supplementation during pregnancy and allergic sensitization at age 2 yr or asthma at age 6–7 yr. Borderline significant inverse association between maternal RBC folate level in the last trimester of pregnancy and asthma at age 6–7 yr (P = 0.05) |

Potential selection bias (∼ 28% of children not followed up to 7 yr and ∼ 67% had no RBC folate level), and nonassessment of maternal dietary intake at any time or of RBC folate in early pregnancy |

| Kiefte-de Jong et al. (37) |

Birth cohort study of 8,742 Dutch children followed up to age 4 yr |

Nonfasting maternal plasma folate level in the first trimester of pregnancy was significantly associated with increased odds of eczema but not with asthma at age 4 yr |

Short duration of follow-up and limited phenotypic assessment of asthma or atopy |

| Haberg et al. (38) | Case-control study (nested within a birth cohort study) of 1,962 Norwegian children followed up to age 3 yr | Maternal plasma folate level in the second trimester of pregnancy was significantly and linearly associated with increased odds of asthma. | Nonassessment of dietary intake, short duration of follow-up, and limited phenotypic assessment of asthma or atopy |

Definition of abbreviations: LRI = lower respiratory infection; RBC = red blood cell.

Cross-sectional studies allow initial examination of a scientific question but cannot establish a temporal relationship between the exposure and outcome of interest. Seven cross-sectional studies have yielded conflicting findings for folate and asthma or atopy (15, 16, 21–24) (Table 1).

Although three case-control studies with small sample size (including preschool children [24], adolescents [16], and adults [22]) found no significant association between dietary intake (16) or serum level of folate (22, 24) and asthma (16, 22) or atopic dermatitis (24), a larger case-control study of 1,030 British adults found a significant inverse association between dietary folate intake and physician-diagnosed asthma (adjusted [a] odds ratio [OR] for each quintile increase in intake = 0.89, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.81–0.98) (25). In contrast to findings from case-control studies, a cross-sectional study of 1,601 Australian adults showed that dietary intake of folate was positively associated with having ever had physician-diagnosed asthma (OR for each μg = 2.2, 95% CI = 1.2–3.9) but not with current asthma, airway responsiveness, or atopy (23). In another cross-sectional study, serum folate was inversely associated with wheeze (aOR for comparison of the highest and lowest quintile = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.4–0.8) or atopy (aOR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.6–0.9) but not with physician-diagnosed asthma in 8,083 children and adults (age range = 2–85 yr) in the United States (21). In Denmark, a study of 6,784 adults found that a low serum folate was significantly associated with physician-diagnosed asthma (aOR for comparison of lowest versus highest quartile = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.05–1.79) but not with impaired lung function, airflow obstruction, or atopy (15).

In summary, although all cross-sectional studies of folate and asthma have been limited by potential selection bias, evidence from four studies with adequate sample size (15, 21, 23, 25) is weak and inconsistent: two reported negative findings for (physician-diagnosed [21] or current [23]) asthma, one reported an inverse association between dietary folate intake and physician-diagnosed asthma (25), and another reported an inverse association between serum folate and physician-diagnosed asthma but no association with airflow obstruction (15).

Longitudinal studies are well suited to study whether folate status is temporally associated with asthma or atopy. To date, 13 such studies (including 11 birth cohorts) have been published (Table 2). A recent study that assessed serum folate (at ages 2, 4, 6, and 8 yr) in 138 U.S. children found that approximately 75% of participants had relatively stable folate levels throughout the study (Cluster A). Compared with this Cluster A, the remaining participants (Cluster B) had significantly higher serum folate levels at ages 2 to 6 years but not at age 8 years (26). In this study, increased serum folate levels were significantly associated with allergic sensitization (to aeroallergens and food allergens) but not with total IgE at ages 6 and 9 years (26). There was no significant association between serum folate and asthma or wheezing at age 6 years. Another study by the same group examined serum folate and disease severity or control in 144 inner-city children (aged 5–17 yr) with persistent asthma over 1 year of follow-up (27). In this study, children with a folate level in the second quartile had a total IgE that was higher than those with a folate level in the lowest quartile but not significantly different from those in the third or fourth quartile. Serum folate was not significantly associated with fractional exhaled nitric oxide, lung function, hospitalizations for asthma, or asthma symptoms (1). Interpretation of the findings of the two studies above is limited by small sample size, potential selection bias, and limited adjustment for probable confounders.

Birth cohort studies are best suited to examine the question posed by experimental studies (8): does folic acid supplementation during pregnancy lead to an increased risk of asthma or atopy? Three such studies examined maternal folate intake during pregnancy (through diet [28, 29] or use of supplements [30]) and wheeze at or before age 2 years (28–30) (when this symptom may represent transient wheeze and not asthma). In a study of 32,077 children in Norway (where food was not fortified with folic acid), maternal self-reported use of folic acid supplements in the first trimester of pregnancy was significantly associated with modestly increased risks of wheeze (adjusted relative risk = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.03–1.10), lower respiratory infections (LRIs), and hospitalizations for LRIs in the first 18 months of life (30). In contrast, Miyake and colleagues reported no significant association between maternal dietary intake of folate at any trimester of pregnancy and either wheeze or eczema in 763 Japanese children aged 18 to 24 months (28). Similarly, a study of 1,290 mother-child pairs in Boston found no significant association between maternal dietary intake of folic acid in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy and either wheeze or eczema at age 2 years (29). Differences between the study from Norway (30) and the other two studies (28, 29) include selection/retention of participants, sample size, and timing of and approach to assessing folate status.

All five birth cohort studies that examined questionnaire-based maternal folate status during pregnancy and asthma or allergies at or after age 5 years (31–35) were limited by significant loss of follow-up at school age (approximately 16–62%). Of these five studies, four yielded negative results (31, 33–35): two of these null studies relied solely on reported use of folic acid supplements at any trimester (35) or in the first/second trimester of pregnancy (33), whereas the other two assessed maternal folate status (by reported dietary intake or use of folic acid supplements) after the first trimester (31, 34). One of these four negative studies focused on children at risk for diabetes mellitus type I (31). The only study to show a significant association between maternal use of folic acid supplements (in late pregnancy) and asthma after age 3 years had limited phenotypic assessment of asthma or atopy and significant (approximately 24%) loss of follow-up of participants at age 5.5 years (32).

Three birth cohort studies have examined circulating or intracellular (using RBC folate) maternal folate status during pregnancy and asthma in offspring (36–38). In a study of 2,834 Dutch children, maternal intracellular folate status (measured in the third trimester of pregnancy in 837 [29.5%] participants) was not significantly associated with allergic sensitization at age 2 years or asthma or lung function at age 6 to 7 years (36). In this study, there was also no significant association between maternal report of folic acid supplementation at any trimester of pregnancy and asthma or other outcomes in 1,902 (72.1%) of the participants at age 6 to 7 years. Although the overall results were consistent, and the phenotypic assessment of asthma was adequate, this study was limited by potential selection bias and nonassessment of folate status in the first or second trimester of pregnancy (36). A second, larger birth cohort study of Dutch children (n = 8,742) found that nonfasting maternal plasma levels of folate or vitamin B12 during the first trimester of pregnancy were significantly associated with increased odds of atopic dermatitis but not with asthma at age 4 years (37). In contrast to the negative findings for asthma in the Dutch studies, a case-control study of 1,962 Norwegian children (nested within a birth cohort) found a significant linear association between maternal plasma folate in the second trimester of pregnancy and asthma at age 3 years (38). Due to short duration of follow-up, both the second Dutch study (37) and the Norwegian study (38) are limited by potential misclassification of asthma.

In summary, all 11 birth cohort studies of folate and asthma or atopy were limited by lack of data on either maternal dietary intake or folate level in early pregnancy (Table 2). Seven of these studies yielded negative findings: three did not follow children up to age 6 years (when a diagnosis of asthma would be more accurate), and the other four had substantial loss of follow-up at or after age 6 years (which may lead to selection bias). Findings from four positive studies must also be cautiously interpreted because of short follow-up (1.5–4 yr), limited phenotypic assessment, and (in two instances) inconsistent results for asthma and atopy or atopic diseases. In spite of the limitations discussed above, birth cohort studies offer weak and inconsistent evidence for an effect of maternal folate status on childhood asthma. Findings from the largest birth cohort study to date suggest that maternal folic acid supplementation may weakly increase the risk of wheeze and LRIs in early childhood (30).

Gene-By-Folate Interactions on Asthma or Atopy

Homozygosity for a common coding mutation (C677T) in MTHFR is associated with reduced enzymatic activity of the coded protein (39), increased risk of a low folate status (15), and reduced genomic (global) DNA methylation in subjects with low folate status (40).

An association between MTHFR C677T genotype and atopy or atopic asthma was reported in studies in Denmark (41) and China (42) but not replicated in subsequent studies in Denmark (15) and the United Kingdom (34). Among 1,482 Danish adults, subjects who were homozygous for the T allele of the C677T mutation in MTHFR had increased odds of atopy (aOR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.2–2.6, P < 0.01) (41). In this study, the estimated effect of dietary folate intake on atopy was only significant in homozygous TT subjects (aOR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.5–0.9) (41). In contrast, a large birth cohort study of British children (n = 5,364) and their mothers (n = 7,356) found no significant association between the C677T mutation and atopy or asthma in participating mothers or their children (34). Moreover, this study found no significant interaction between the C677T mutation and dietary folate intake on atopy or asthma. Limitations of published studies of MTHFR and asthma or atopy include nonmeasurement of biomarkers (15, 34, 41, 42), potential selection bias (34, 42), and limited assessment of atopy or asthma (41, 42).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Extrapolating findings from animal studies to humans is challenging. For example, the experimental study on gestational dietary supplementation of methyl donors and AAD was performed in a single strain of mice that received what would be high to very high doses of methyl donors in humans. Of note, exclusive folate supplementation during pregnancy was not evaluated in that experimental study.

In many countries, patterns of folate intake have changed due to fortification programs and maternal supplementation. In the U.S. population, mean serum folic acid levels after fortification (1999–2010) were 2.5 times higher than those measured during an earlier period (1988–1994) (43). Because the prevalence of asthma in the United States and other industrialized nations was rising before food fortification with folic acid or widespread use of maternal folate supplementation (44), changes in maternal folate status are an unlikely explanation for the “asthma epidemic.” Consistent with these ecologic observations, findings from cross-sectional or birth cohort studies (Tables 1 and 2) do not support a moderate or strong association between folate status and asthma. Given known benefits of folic acid supplementation during conception and pregnancy on preventing neural tube and cardiac defects, there is no reason to alter existing recommendations based on findings for folate and asthma or atopy.

In contrast to the relatively large number of studies of folate status and asthma per se, the relation between folate status and asthma severity or control has only been assessed in two studies with small sample size and thus limited statistical power.

Although we believe that there are inadequate data to exclude a weak or modest effect of maternal folate status on asthma or asthma symptoms, such an effect should and could be examined within the context of ongoing (very large) birth cohort studies (e.g., Reference 30). Similarly, secondary analyses of existing studies of subjects with asthma could help assess whether folate status has any role in disease severity or control in subjects with asthma. At this time, there is no justification for funding de novo studies of folate and asthma.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL079966 and an endowment from the Heinz Foundation.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0317PP on May 7, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, Zahran HS, King M, Johnson CA, Liu X.Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief, no 94. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [PubMed]

- 2.Allan K, Devereux G. Diet and asthma: nutrition implications from prevention to treatment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai CK, Beasley R, Crane J, Foliaki S, Shah J, Weiland S International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Three Study Group. Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. 2009;64:476–483. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.106609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul G, Brehm JM, Alcorn JF, Holguín F, Aujla SJ, Celedón JC. Vitamin D and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:124–132. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1502CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller RL, Ho SM. Environmental epigenetics and asthma: current concepts and call for studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:567–573. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1511PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovinsky-Desir S, Miller RL. Epigenetics, asthma, and allergic diseases: a review of the latest advancements. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012;12:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s11882-012-0257-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niculescu MD, Zeisel SH. Diet, methyl donors and DNA methylation: interactions between dietary folate, methionine and choline. J Nutr. 2002;132:2333S–2335S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2333S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollingsworth JW, Maruoka S, Boon K, Garantziotis S, Li Z, Tomfohr J, Bailey N, Potts EN, Whitehead G, Brass DM, et al. In utero supplementation with methyl donors enhances allergic airway disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3462–3469. doi: 10.1172/JCI34378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Iyer R, Tomar SK. Folate: a functional food constituent. J Food Sci. 2009;74:R114–R122. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caudill MA. Folate bioavailability: implications for establishing dietary recommendations and optimizing status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1455S–1460S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang PK, Gordon RK, Tal J, Zeng GC, Doctor BP, Pardhasaradhi K, McCann PP. S-Adenosylmethionine and methylation. FASEB J. 1996;10:471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey LB, Gregory JF., III Folate metabolism and requirements. J Nutr. 1999;129:779–782. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.4.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shane B. Folate status assessment history: implications for measurement of biomarkers in NHANES. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:337S–342S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.013367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clifford AJ, Noceti EM, Block-Joy A, Block T, Block G. Erythrocyte folate and its response to folic acid supplementation is assay dependent in women. J Nutr. 2005;135:137–143. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thuesen BH, Husemoen LL, Ovesen L, Jørgensen T, Fenger M, Gilderson G, Linneberg A. Atopy, asthma, and lung function in relation to folate and vitamin B(12) in adults. Allergy. 2010;65:1446–1454. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bueso AK, Berntsen S, Mowinckel P, Andersen LF, Lødrup Carlsen KC, Carlsen KH. Dietary intake in adolescents with asthma—potential for improvement. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNulty H, Scott JM. Intake and status of folate and related B-vitamins: considerations and challenges in achieving optimal status. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:S48–S54. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508006855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Signorello LB, Buchowski MS, Cai Q, Munro HM, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. Biochemical validation of food frequency questionnaire-estimated carotenoid, alpha-tocopherol, and folate intakes among African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites in the Southern Community Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:488–497. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brand S, Kesper DA, Teich R, Kilic-Niebergall E, Pinkenburg O, Bothur E, Lohoff M, Garn H, Pfefferle PI, Renz H.DNA methylation of TH1/TH2 cytokine genes affects sensitization and progress of experimental asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol2012. 129:1602–1610.e6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Allan RS, Zueva E, Cammas F, Schreiber HA, Masson V, Belz GT, Roche D, Maison C, Quivy JP, Almouzni G, et al. An epigenetic silencing pathway controlling T helper 2 cell lineage commitment. Nature. 2012;487:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature11173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui EC, Matsui W.Higher serum folate levels are associated with a lower risk of atopy and wheeze. J Allergy Clin Immunol2009. 123:1253–1259.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Farres MN, Shahin RY, Melek NA, El-Kabarity RH, Arafa NA. Study of folate status among Egyptian asthmatics. Intern Med. 2011;50:205–211. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woods RK, Walters EH, Raven JM, Wolfe R, Ireland PD, Thien FC, Abramson MJ. Food and nutrient intakes and asthma risk in young adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:414–421. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaheen MA, Attia EA, Louka ML, Bareedy N. Study of the role of serum folic acid in atopic dermatitis: a correlation with serum IgE and disease severity. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:673–677. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.91827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel BD, Welch AA, Bingham SA, Luben RN, Day NE, Khaw KT, Lomas DA, Wareham NJ. Dietary antioxidants and asthma in adults. Thorax. 2006;61:388–393. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.024935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okupa AY, Lemanske RF, Jr., Jackson DJ, Evans MD, Wood RA, Matsui EC.Early-life folate levels are associated with incident allergic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol2013. 131:226–228.e1–e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lin JH, Matsui W, Aloe C, Peng RD, Diette GB, Breysse PN, Matsui EC.Relationships between folate and inflammatory features of asthma J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:918–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K, Hirota Y. Maternal B vitamin intake during pregnancy and wheeze and eczema in Japanese infants aged 16-24 months: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litonjua AA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Ly NP, Tantisira KG, Rich-Edwards JW, Camargo CA, Jr, Weiss ST, Gillman MW, Gold DR. Maternal antioxidant intake in pregnancy and wheezing illnesses in children at 2 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:903–911. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Håberg SE, London SJ, Stigum H, Nafstad P, Nystad W. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and early childhood respiratory health. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:180–184. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.142448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nwaru BI, Erkkola M, Ahonen S, Kaila M, Kronberg-Kippilä C, Ilonen J, Simell O, Knip M, Veijola R, Virtanen SM. Intake of antioxidants during pregnancy and the risk of allergies and asthma in the offspring. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:937–943. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitrow MJ, Moore VM, Rumbold AR, Davies MJ. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:1486–1493. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinussen MP, Risnes KR, Jacobsen GW, Bracken MB.Folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy and asthma in children aged 6 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol2012. 206:72.e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Granell R, Heron J, Lewis S, Davey Smith G, Sterne JA, Henderson J. The association between mother and child MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, dietary folate intake and childhood atopy in a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:320–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bekkers MB, Elstgeest LE, Scholtens S, Haveman-Nies A, de Jongste JC, Kerkhof M, Koppelman GH, Gehring U, Smit HA, Wijga AH. Maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy, and childhood respiratory health and atopy. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1468–1474. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00094511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magdelijns FJ, Mommers M, Penders J, Smits L, Thijs C. Folic acid use in pregnancy and the development of atopy, asthma, and lung function in childhood. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e135–e144. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiefte-de Jong JC, Timmermans S, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Tiemeier H, Steegers EA, de Jongste JC, Moll HA. High circulating folate and vitamin B-12 concentrations in women during pregnancy are associated with increased prevalence of atopic dermatitis in their offspring. J Nutr. 2012;142:731–738. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.154948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Håberg SE, London SJ, Nafstad P, Nilsen RM, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, Nystad W.Maternal folate levels in pregnancy and asthma in children at age 3 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol2011. 127:262–264.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, Boers GJ, den Heijer M, Kluijtmans LA, van den Heuvel LP, et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10:111–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friso S, Choi SW, Girelli D, Mason JB, Dolnikowski GG, Bagley PJ, Olivieri O, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Corrocher R, et al. A common mutation in the 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene affects genomic DNA methylation through an interaction with folate status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5606–5611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062066299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Husemoen LL, Toft U, Fenger M, Jørgensen T, Johansen N, Linneberg A. The association between atopy and factors influencing folate metabolism: is low folate status causally related to the development of atopy? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:954–961. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou CC, Tang LF, Jiang MZ, Zhao ZY, Hirokazu T, Mitsufumi M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase [correction of reducatase] polymorphism and asthma [in Chinese] Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2003;26:161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pfeiffer CM, Hughes JP, Lacher DA, Bailey RL, Berry RJ, Zhang M, Yetley EA, Rader JI, Sempos CT, Johnson CL. Estimation of trends in serum and RBC folate in the U.S. population from pre- to postfortification using assay-adjusted data from the NHANES 1988-2010. J Nutr. 2012;142:886–893. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.156919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ownby DR. Has mandatory folic acid supplementation of foods increased the risk of asthma and allergic disease? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1260–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]