Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of activated Rho GTPase cell division control protein 42 homolog (Cdc42) in colorectal cancer cell adhesion, migration, and invasion.

Material/Methods

The constitutively active form of Cdc42 (GFP-Cdc42L61) or control vector was overexpressed in the colorectal cancer cell line SW480. The localization of active Cdc42 was monitored by immunofluorescence staining, and the effects of active Cdc42 on cell migration and invasion were examined using an attachment assay, a wound healing assay, and a Matrigel migration assay in vitro.

Results

Immunofluorescence staining revealed that constitutively active Cdc42 predominately localized to the plasma membrane. Compared to SW480 cells transfected with the control vector, overexpression of constitutively active Cdc42 in SW480 cells promoted filopodia formation and cell stretch and dramatically enhanced cell adhesion to the coated plates. The wound healing assay revealed a significant increase of migration capability in SW480 cells expressing active Cdc42 compared to the control cells. Additionally, the Matrigel invasion assay demonstrated that active Cdc42 significantly promoted SW480 cell migration through the chamber.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that active Rho GTPase Cdc42 can greatly enhance colorectal cancer cell SW480 to spread, migrate, and invade, which may contribute to colorectal cancer metastasis.

Keywords: Rho GTPase Cdc42, colorectal cancer, cell invasion, cell migration

Background

Small Rho GTPases act as molecular switches to control a variety of functions, including actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, membrane trafficking, cell-cycle progression, exocytosis, mitogenesis, and cell survival in response to diverse extracellular stimuli [1]. Cdc42 is part of the small Rho GTPase family, which cycles between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state. Stimuli such as integrins, growth factors, cytokines and cadherins can activate Cdc42, which then interact with different downstream effectors [2,3]. A well characterized effector, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), links Cdc42 to actin polymerization through the actin-related protein-2/3 (Arp2/3) complex. Arp2/3 promotes actin nucleation and polymerization to form actin-enriched structures, such as filopodia and actin microspikes. Cdc42 is also responsible for cell polarization and the Golgi apparatus reorientation toward the leading edge during cell migration [4].

Aberrant Cdc42 expression or activation has been reported in a set of malignancies, including breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, and testicular cancer [5]. Recently, accumulating evidence has suggested the important roles of Cdc42 in the development and progression of cancer. An increase of Cdc42 protein expression level is involved in melanoma tumorigenesis, and surface antigen-induced Cdc42 activation promotes melanoma cell growth and cell invasion [6]. Colorectal cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in both men and women worldwide. Even though great progress in colorectal cancer therapy has been made, the biggest challenge for treatment is the recurrence and metastasis of colon cancer. Elevation of Cdc42 protein expression has been reported to be approximately 60% incidence in colorectal cancer patients [7]. Such overexpression is positively correlated with the histopathological grade in colorectal cancer, which suggests the possible role of Cdc42 in colon cancer cell polarity and actin cytoskeleton reorganization [7]. Many factors are believed to be involved in the recurrence and metastasis of colorectal cancer; however, the effects of Cdc42 on the adhesion, migration, and invasion of human colorectal cancer cells have not been investigated.

To analyze whether Cdc42 plays a role in the migration of colorectal cancer cells, transient transfectants of constitutively active Cdc42L61 and a control vector were generated in the human colorectal cancer cell line SW480. The effects of active Cdc42 on cell adhesion, migration, and invasiveness were investigated. Our results suggest a potential role of Cdc42 in colorectal cancer metastasis.

Material and Methods

Cell line and DNA constructs

The human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line SW480 was obtained from the China Type Culture Collection. SW480 cells were maintained in PRMI1640 (Life Technologies, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS)(Gibco) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. The N-terminally GFP-tagged human Cdc42L61 plasmid and control vector were kindly provided by Dr. Staffan (Karolinska Institute, Sweden).

Transient transfection and Western blotting analysis

SW480 cells were plated in 6-well plates. The following day, subconfluent cells were transfected with 3 ug of GFP-Cdc42L61 or an empty vector using FuGENE6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested and lysed in a lysis buffer 48 hours after transfection. Then, 20 μg of cell lysates were separated with 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Sigma). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk in 0.1% Tween-20 Tris buffered saline (TBST) for 2 hours at room temperature (RT) and incubated with specific monoclonal antibodies against GFP (1:1000, BD Biosciences) or β-actin (1:1000, Sigma) overnight at 4°C. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling) for 1 hour at RT. Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific) and β-actin served as the loading control.

Immunofluorescence staining

SW480 cells transfected with GFP-Cdc42L61 or an empty vector were cultured on glass coverslips for 3 hours in PBS, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. F-actin was stained with rhodamine phalloidin. Stained cells were mounted with SlowFade Gold (Invitrogen). Cells were visualized and photographed using a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope.

Attachment assay

Cells were plated on 48-well plates, and then were coated with 10 μg/ml extracellular matrices (ECM) (Life Technologies, Inc.) in PBS overnight at 4°C. Then, the cells were blocked for 60 minutes at 37°C with 200 μl of 1% heat denatured BSA in PBS and washed with PBS. Transfected SW480 cells were trypsinized and suspended in adhesion buffer at 50 000 cells/100 μl/well. After incubating the plates at 37°C for 30 minutes, 100 μl fresh adhesion buffer and 15 μl 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) dye were added to the wells followed by an additional incubation for at least 3 hours at 37°C. Then, 100 μl of solubilization solution containing 0.05 M HCl in 2-propanol (37% 1:240) was added into each well and incubated for 1 hour. Finally, 100 μl of colored solution was transferred from each well to the corresponding well in 96-well plates to measure the OD550 value.

Wound healing assay

Transfected SW480 cells were plated on gridded dishes. Confluent monolayers of cells were scratched with a 10 μl pipette tip. The same wound area was photographed at 0 and 36 hours after wounding under a Zeiss Axioskop microscope. A cell-free region was drawn and measured by Image J software. At least 8 different wounds and 3 independent experiments were performed.

Matrigel invasion assay

A BioCoat™ Matrigel invasion chamber was used according to the manufacturer’s instruction (BD Biosciences). Briefly, 5×106 cells transfected with GFP-Cdc42L61 or an empty vector were trypsinized, washed, resuspended in 200 μl of serum-free medium Leibovitz L-15 supplemented with glutamine, and seeded in the upper portion of the invasion chamber. The lower portion of the chamber contained 500 μl of full medium, which served as a chemoattractant. After 4 hours, cells that invaded through the Matrigel and migrated to the bottom chamber were fixed with 100% methanol, stained with 1% methylene blue, photographed, and counted.

Statistical methods

Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unpaired or paired Student t-tests were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, USA) software. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Ectopic expression of constitutively active Cdc42 in colorectal cancer cell SW480

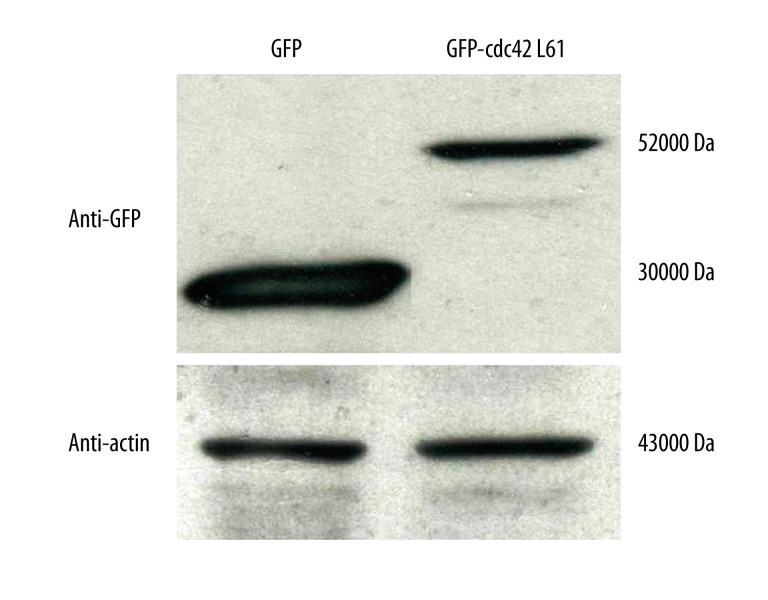

The contribution of Cdc42 to different cellular processes is cell-type specific [1]. In addition, Cdc42 expression correlates with the histopathological grade of colorectal cancer [7]. In view of these observations, we hypothesized that Cdc42 was involved in the regulation of colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion. To directly examine the downstream effects of Cdc42 in colorectal cancer cells, we used constitutively active Cdc42L61 and expressed it in SW480 cells. Cdc42L61 is defective in GTP hydrolysis and has been widely used in Cdc42 studies [4]. The overexpression of Cdc42L61 was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ectopic expression of constitutively active Cdc42L61 in colorectal cancer SW480 cells Western blot analysis revealed the expression of GFP-tagged human Cdc42L61 (52 kDa) and control vector (30 kDa) in SW480 cells. β-actin (43 kDa) served as a loading control.

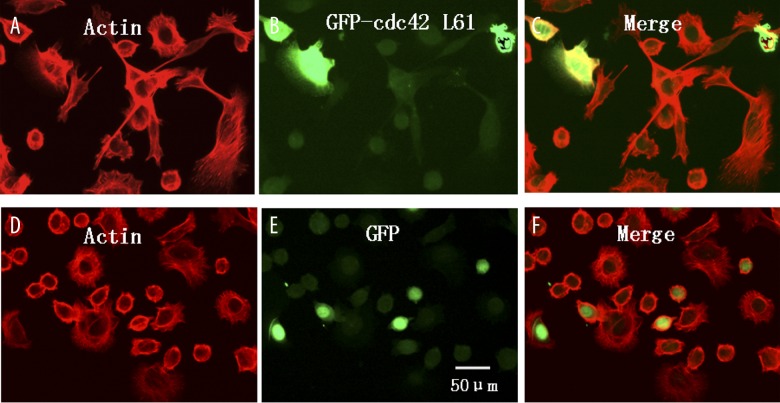

Activation of Cdc42 promotes SW480 cell focal adhesion and stretch

Before performing any functional assay, it was critical to validate the mutant, Cdc42L61, as a proper tool to be used in this system. Previous studies showed that in certain stimulated cells, such as PC-12, Cdc42 was activated and localized predominately to the plasma membrane [8]. Consistently, immunofluorescence staining revealed that ectopically expressed Cdc42L61 in SW480 cells was mainly localized at the plasma membrane, whereas control GFP localized in the cytoplasm, suggesting that Cdc42L61 could mimic the GTP-bounded form of Cdc42, which interacts with some plasma membrane-anchored proteins (Figure 2B, 2E). To test our hypothesis, we first examined the effect of active Cdc42 on colon cancer cell adhesion. Four hours after transfection, SW480 cells were re-plated onto coated coverslips for another 48 hours. Cells were then fixed and processed for indirect immunofluorescence staining. We observed that the expression of Cdc42L61 significantly increased filopodia formation and cell stretch in SW480 cells compared to the control vector (Figure 2). In addition, the attachment assay revealed that activated Cdc42 significantly increased SW480 cell adhesion to the coated coverslips compared to the control cells. The OD550 values of the Cdc42L61 expressing cells and control cells were 1.28±0.15 and 0.83±0.12, respectively (P<0.001, Figure 3). The data suggest that activated Cdc42 enhanced the focal adhesion and attachment of colorectal cancer cells

Figure 2.

Constitutively active Cdc42L61 promoted SW480 cell focal adhesion in vitro. Images of SW480 cells transfected with GFP-Cdc42L61 (A–C) or a control vector (D–F) were captured under an immunofluorescence microscope with F-actin in red (A and D), GFP in green (B and E), and merged pictures (C and F). Immunofluorescence staining revealed that expression of GFP-Cdc42L61 increased SW480 cell focal adhesion and stretch.

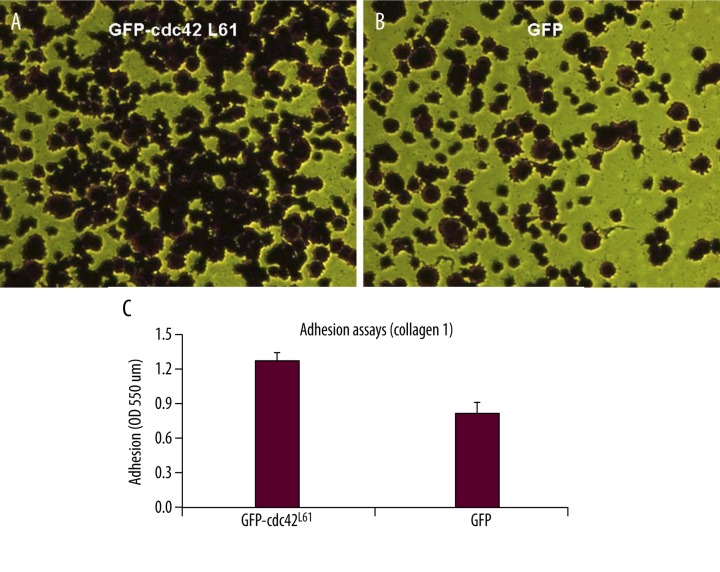

Figure 3.

Constitutively active Cdc42L61 enhanced SW480 cell attachment in vitro. (A and B) Attachment assays were performed with GFP-Cdc42L61 expressing SW480 or control cells, and representative images of SW480 cell attachment on coated coverslips were shown. (C) OD550 values of attached cells were expressed as means ±S.E.M. (n=3, P<0.001).

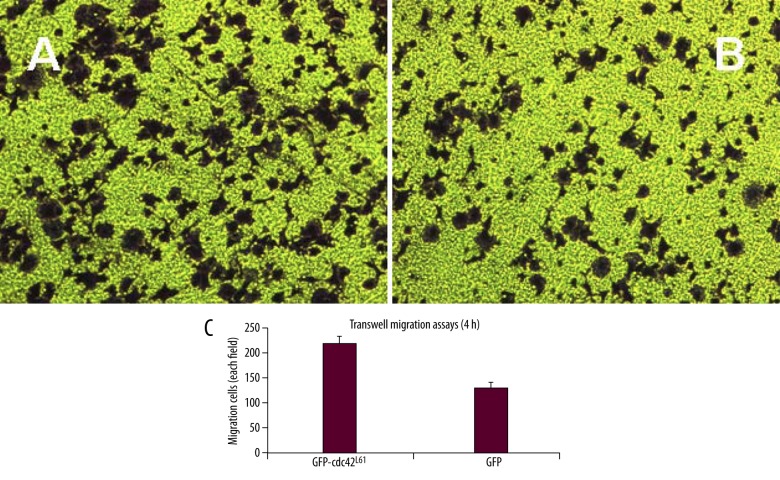

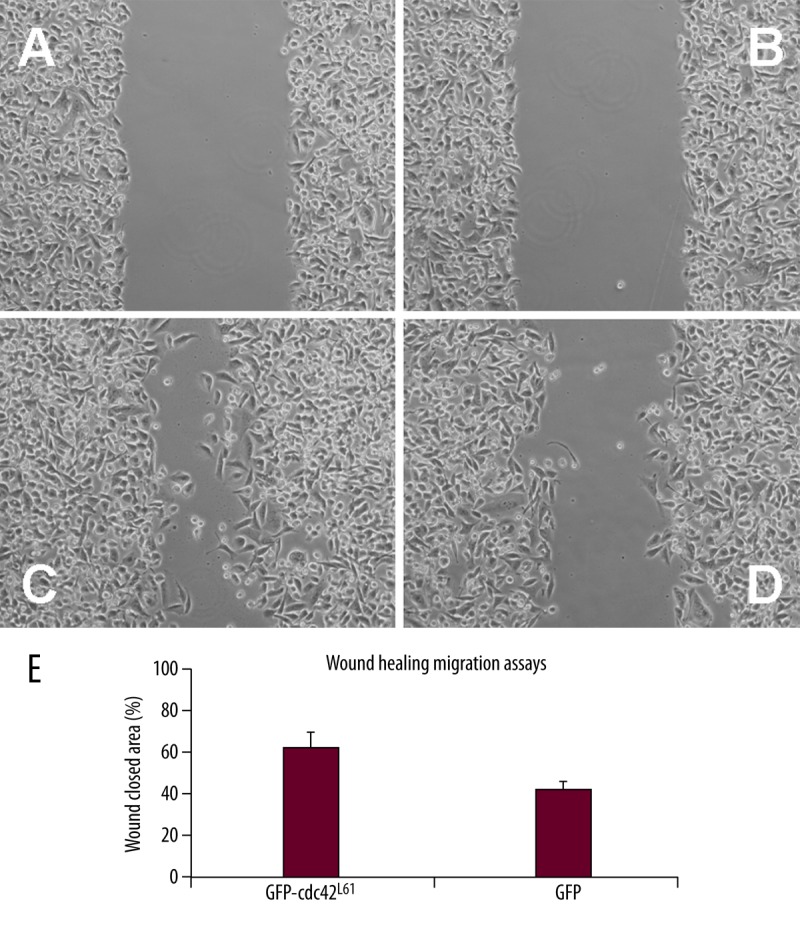

Activation of Cdc42 increases colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion

To test the effect of active Cdc42 on SW480 cell migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells, we first performed a wound healing assay. SW480 cells were transfected with vectors expressing Cdc42L61 or control GFP vectors. The migration speed of SW480 cells expressing Cdc42L61 or a control vector was analyzed 36 hours after scratching. This assay revealed that constitutively active Cdc42L61 significantly increased SW480 cell migration from 37±5% to 61±7% (P<0.001, Figure 4). Finally, we performed a Matrigel invasion assay, a widely used method to evaluate the cell migration ability in vitro. We observed that SW480 cells expressing Cdc42L61 migrated significantly better through wells to the bottom chamber 72 hours after seeding the transfected cells in the top chamber in response to the serum gradient compared to the control cells (P<0.001, Figure 5). Together, these findings indicate that constitutively active Cdc42L61 promoted SW480 colorectal cancer cell adhesion, migration, and invasion.

Figure 4.

Cdc42L61 increased SW480 cancer cell migration. (A–D) Wound healing assays were performed with SW480 cells expressing GFP-Cdc42L61 or control cells, and representative images of SW480 cells around the wound area 0 and 36 hours after wounding were shown. (E) Cell migration speed at wound area was quantified (n=3, P<0.001).

Figure 5.

Active Cdc42L61 promoted SW480 cancer cell invasion. Transwell invasion assays were carried out with SW480 cells transfected with GFP-Cdc42L61 (A) or an empty vector (B). (C) Cell transwell invasion was quantified by counting cells that had invaded through the chamber under a light microscope. Cells in 4 fields per well were counted and assays were completed in triplicate (n=3, P<0.001).

Discussion

Cdc42, an important Rho GTPase, has been shown to be important in chemotaxis and directed migration in several cell types, both in vitro and in vivo[9]. Knockdown of Cdc42 in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) caused aberrant cell spreading, decreased adhesion to fibronectin, impaired mobility in wound healing, and reduced chemotaxis toward a serum gradient [10]. In addition, increased Cdc42 enzymatic activity stimulated migration speed in neutrophils [11]. However, Cdc42-depleted fibroblastoid cells showed comparable migration ability compared with wild-type fibroblastoid cells, indicating that the function of Cdc42 was cell-type specific [12]. In solid tumors, it has been reported that autotaxin promotes melanoma cell invasiveness and angiogenesis through Cdc42 [6]. Cdc42 overexpression in colon cancer is significantly correlated with the histopathological grade of colorectal cancer [7]. Moreover, leptin-induced Cdc42 activation promotes lamellipodium formation and therefore enhances cell invasion in human colon cancer cells [13]. Consistently, our current study showed that constitutively active Cdc42 significantly promoted colorectal cancer cell invasion and migration toward a serum gradient in vitro.

Increasing lines of evidence have shown that Cdc42 contributes to cancer development and progression through different mechanisms, including cell cycle regulation and survival, polarity, migration, and transcriptional regulation [5,14]. Conversely, certain studies demonstrated that depending on the cellular context, Cdc42 could either promote or inhibit tumor progression. It appears that Cdc42 functions as a pro-oncogenic factor in the majority of cell types [5]. For example, overexpression of Cdc42 promotes colon cancer progression by significantly suppressing the putative tumor suppressor gene ID4 [7]. Our findings strongly support the finding that Cdc42 enhanced colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion, which might have partly accounted for colon cancer progression.

Moreover, our current study used the constitutively active Cdc42L61, which was impaired in GTP hydrolysis, but was active state in the cells. This allowed us to directly observe the long-term effects of Cdc42 activation on colon cancer cell migration, and might have better mimicked the human colorectal cancer cells with stimulus-induced Cdc42 activation.

Multiple effector pathways have been indicated in Cdc42 signaling to the actin cytoskeleton and nucleus, such as the p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1)-regulated myosin light chain (MLC) and MAP kinase 1 (MEK1) [15–17]. The activation of Cdc42 is also tightly regulated by activating proteins and upstream signals [18]. Because Cdc42 is ubiquitously expressed and plays a central role in controlling multiple signal transduction pathways that drive cell migration, a major challenge in future studies is to determine the cell type- and stimulus-specific signaling mechanisms and function of Cdc42 in diverse systems under physiological or pathological conditions.

Conclusions

We provided evidence that Cdc42 plays a direct role in regulating colorectal cancer cell migration. These findings provide a rationale for targeting Cdc42 and related pathways as a novel approach to colon cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Additional studies are required to determine the precise mechanisms by which Cdc42 activation promotes colon cancer progression and metastasis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Siyang Xu and Jiulong Dai for their comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of support: The research was supported by the National Natural Science funds (81170345)

References

- 1.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2001;420:629–35. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossman KL, Der CJ, Sondek J. GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotideexchange factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:167–80. doi: 10.1038/nrm1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vega FM, Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases in cancer cell biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(14):2093–101. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung ID, Lee J, Yun SY, et al. Cdc42 and Rac1 are necessary for autotaxin-induced tumor cell motility in A2058 melanoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;532(3):351–56. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez Del Pulgar T, Valdes-Mora F, Bandres E, et al. Cdc42 is highly expressed in colorectal adenocarcinoma and downregulates ID4 through an epigenetic mechanism. Int J Oncol. 2008;33(1):185–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha S, Yang W. Cellular signaling for activation of Rho GTPase Cdc42. Cell Signal. 2008;20(11):1927–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossman KL, Der CJ, Sondek J. GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2005;l6:167–80. doi: 10.1038/nrm1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang L, Wang L, Zheng Y. Gene targeting of Cdc42 and Cdc42GAP affirms the critical involvement of Cdc42 in filopodia induction, directed migration, and proliferation in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(11):4675–85. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szczur K, Xu H, Atkinson S, et al. Rho GTPase CDC42 regulates directionality and random movement via distinct MAPK pathways in neutrophils. Blood. 2006;108(13):4205–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Zheng Y. Cell type-specific functions of Rho GTPases revealed by gene targeting in mice. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(2):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe T, Schwartz B. Leptin promotes motility and invasiveness in human colon cancer cells by activating multiple signal-transduction pathways. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(11):2543–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parri M, Chiarugi P. Rac and Rho GTPases in cancer cell motility control. Cell Commun Signal. 2010;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop AL, Hall A. Rho GTPases and their effector proteins. Biochem J. 2000;348(Pt 2):241–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouzahzah B, Albanese C, Ahmed F, et al. Rho family GTPases regulate mammary epithelium cell growth and metastasis through distinguishable pathways. Mol Med. 2001;7(12):816–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zohrabian VM, Forzani B, Chau Z, et al. Rho/ROCK and MAPK signaling pathways are involved in glioblastoma cell migration and proliferation. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(1):119–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon SY, Zheng Y. Rho GTPase-activating proteins in cell regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;13:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]