Abstract

Background

Empirical evidence demonstrates that the Thai Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) has improved equity of health financing and provided a relatively high level of financial risk protection. Several UCS design features contribute to these outcomes: a tax-financed scheme, a comprehensive benefit package and gradual extension of coverage to illnesses that can lead to catastrophic household costs, and capacity of the National Health Security Office (NHSO) to mobilise adequate resources. This study assesses the policy processes related to making decisions on these features.

Methods

The study employs qualitative methods including reviews of relevant documents, in-depth interviews of 25 key informants, and triangulation amongst information sources.

Results

Continued political and financial commitments to the UCS, despite political rivalry, played a key role. The Thai Rak Thai (TRT)-led coalition government introduced UCS; staying in power 8 of the 11 years between 2001 and 2011 was long enough to nurture and strengthen the UCS and overcome resistance from various opponents. Prime Minister Surayud’s government, replacing the ousted TRT government, introduced universal renal replacement therapy, which deepened financial risk protection.

Commitment to their manifesto and fiscal capacity pushed the TRT to adopt a general tax-financed universal scheme; collecting premiums from people engaged in the informal sector was neither politically palatable nor technically feasible. The relatively stable tenure of NHSO Secretary Generals and the chairs of the Financing and the Benefit Package subcommittees provided a platform for continued deepening of financial risk protection. NHSO exerted monopsonistic purchasing power to control prices, resulting in greater patient access and better systems efficiency than might have been the case with a different design.

The approach of proposing an annual per capita budget changed the conventional line-item programme budgeting system by basing negotiations between the Bureau of Budget, the NHSO and other stakeholders on evidence of service utilization and unit costs.

Conclusions

Future success of Thai UCS requires coverage of effective interventions that address primary and secondary prevention of non-communicable diseases and long-term care policies in view of epidemiologic and demographic transitions. Lessons for other countries include the importance of continued political support, evidence informed decisions, and a capable purchaser organization.

Keywords: Continued political support, Financial risk protection, Tax-financed universal scheme, Thailand, Universal health coverage

Background

In 2001, prior to the achievement of universal coverage of health care, approximately 30% of the Thai population were uninsured despite the gradual extension of coverage to various population groups [1]. Universal coverage was achieved in 2002 [2] under the leadership of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra of the Thai Rak Thai (TRT) party. Beneficiaries in the Medical Welfare Schemes, the publicly subsidized voluntary insurance scheme, and the uninsured 30% of the population, were combined and covered by a new universal coverage scheme (UCS), financed through general taxation. The Civil Servant Medical Benefit scheme (CSMBS) and Social Health Insurance (SHI) for public and private sector employees remained as independent schemes. Detailed features of all the three schemes have been described elsewhere [3].

Evidence on equity and financial risk protection of UCS

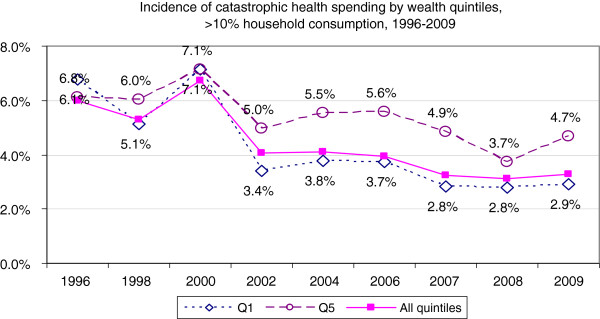

As a result of continued assessment [4], evidence shows increased equity of health financing and improved financial risk protection with the introduction of universal coverage [5]. First, there is progressive tax financing for the UCS as the rich pay a higher proportion of their income in taxes than the poor [6]. Second, there is a pro-poor use of health services because the easily accessible district health system is contracted as the provider network [7]. Third, government health spending favoured the poor prior to universal coverage in 2001 and the same trend has continued in subsequent years, in particular at district and provincial hospitals; these pro-poor subsidies were a result of pro-poor utilization [8]. Fourth, there was improved financial risk protection, as measured by the very low incidence of catastrophic health expenditure, which dropped amongst the poorest quintile from 6.8% in 1996 (prior to universal coverage) to 2.9% in 2009, and amongst the richest quintile from 6.1% to 4.7% (Figure 1) [9]. There was a statistically significant difference between rich and poor in all years, except in 2000 (P = 0.667) [9].

Figure 1.

Incidence of catastrophic health expenditure prior to universal coverage (1996–2000) and after universal coverage (2002–2009), national averages. Note: catastrophic health expenditure refers to household spending on health that exceeds 10% of total household consumption expenditure. Source: Computed by Limwattananon S using the national dataset of household socio-economic surveys conducted by the National Statistical Office.

Finally, the incidence of medical impoverishment is low and decreasing, as measured by the additional number of people falling under the national poverty line because of health payments; this reduced from 11.9% in 2000 (prior to universal coverage) to 8.6% in 2002 and 4.7% in 2009. The main reasons for continuing out-of-pocket expenditure are UCS members choosing private hospital inpatient care [10] not covered by the UCS or bypassing the referral system and hence bearing the full cost.

Features contributing to equity and financial risk protection

Four key system features contribute to the equity outcome and financial risk protection. First, general tax (rather than premium contributions by UCS members) was unanimously chosen as the major source of financing; a small co-payment of THB 30 (US$ 0.7) per visit or admission was applied in 2001 but removed in 2007. Second, universality was adopted in 2001 instead of a targeting policy. Targeting proponents recommended increasing coverage to population subgroups, such as effective coverage of poor households, extension of SHI to cover spouse and children, voluntary enrolment of more self-employed SHI members through flat-rate monthly contributions, boosting the publicly subsidized voluntary insurance scheme for the informal sector, and stimulating private voluntary health insurance uptake by the rich. Advocates for universality promoted the constitutional right to healthcare of all citizens, and argued that it was time that Thailand ended the 27-year struggle with the targeting approach given that 30% of the population was still uninsured by 2001, and that the mechanism to identify the poor was not effective in fully covering the real poor and preventing the non-poor from getting a free health card due to nepotism in the local community. Further, coverage of the voluntary element of SHI was low, as the premium had to be fully paid by individual contributions with no subsidy from employer or government. Third, the option of a basic minimum package was defeated without much debate in favour of a comprehensive package. Furthermore, the National Health Security Office (NHSO) responsible for the UCS has subsequently taken steps to expand coverage to a number of illnesses that can produce catastrophic costs for households, boosting financial risk protection. Fourth, NHSO successfully secured the additional funding needed for the expanded benefit package.

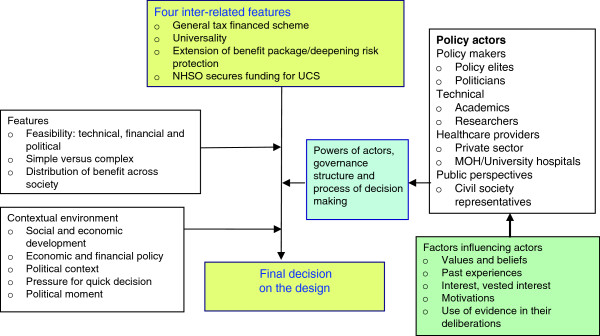

The agenda setting and policy formulation stages of the universal coverage have been fully investigated [11]. Given the centrality of the four inter-related features (general tax finance, universality principle, financial risk protection, and securing adequate funding) to ensuring an equitable outcome and financial risk protection, this study seeks to explain how and why these features came about. How did different actors with varying powers, influence and positions, within the given context of decision-making and governance, interplay in shaping these features?

Methods

In line with the conceptual framework in Figure 2, a policy analysis tool [12] was applied to assess the policy actors, networks and communities [13], and the process and context in relation to decisions on the four inter-related design features. Methods included document reviews and in-depth interviews of key informants (KIs) who were policy actors, including policy elites [14] (the authoritative decision makers who are either supportive or non-supportive or who can be positively or negatively affected by these features), civil society representatives and academia. Ex-ante, a number of KIs were identified from those closely involved with these design elements. The initial interviews were iterative and exploratory; additional KIs were further identified through a snowball process until saturation of evidence. Researchers developed a semi-structured interview guide in line with the conceptual framework which focused on who, when, why and how policy actors interacted and negotiated until the proposed features were adopted. The tool was finalized after testing with two KIs in the NHSO. To ensure consistency, all KIs were interviewed by one co-author; conversations were tape recorded with consent, and transcribed in Thai by two co-authors.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework.

The literature review was performed first, though interviews with KIs were initiated concurrently. Relevant documents were retrieved from the NHSO for analysis, in particular minutes of the monthly meetings of subcommittees on Financing and Benefit Package and of the National Health Security Board (NHSB) between 2003, when the NHSO was set up, and 2010. Information from interviews was triangulated and verified against evidence generated from reviews of relevant documents such as minutes of various meetings and/or with other KIs for accuracy and consistency. A number of re-interviews of KIs were conducted for clarification and to probe related issues.

NVIVO was used for analysis, based on the four features and subthemes that emerged from interviews, namely actors, their power and motivations, interactions amongst them, and the contextual environment within which each feature was discussed, negotiated and adopted.

The study received ethical approval from the WHO and the National Ethics Committee. Data and tapes are securely stored and will be destroyed after five years. Fieldwork was conducted in the second half of 2011. In total, 25 knowledgeable individuals were identified and interviewed. Within these, there were five policy makers, five programme implementers, four academics, five researchers, and six stakeholders (two from CSMBS and SHI, one private provider, two public providers, and one civil society organization). These individuals included both supporters and non-supporters of the four design features, as judged based on the positions they adopted in 2001–2002.

Results and discussion

Continued political support: the UCS survives seven governments in eleven years

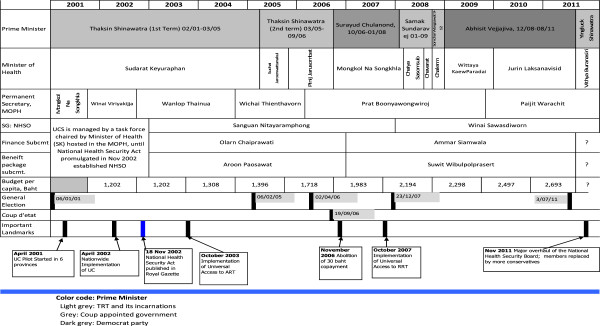

Between 2001 and 2011, the UCS thrived despite seven governments, six elections and one coup d’état, ten Health Ministers who chaired the NHSB, and six Permanent Secretaries who headed the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH). Figure 3 depicts the major events surrounding the UCS.

Figure 3.

Major events relating to the UCS, 2001–2011.

There was a high degree of continuity in managing the UCS. The founding Secretary General (SG), Dr Sanguan Nittayaramphong, previously a high-level policy maker in the MOPH, was acting in charge of the UCS from its inception in April 2001 until the National Health Security Act in November 2002. With the creation of the NHSO, he was then appointed SG and served a full four-year term (2003–2006) which was renewed in 2007. His successor, one of his deputies who was involved from the start, has led NHSO from 2008 to date. Reflections from most KIs see the “relatively stable” (KI 16, policy maker) term of the SG in ensuring continuity of UCS policy development and effective implementation.

Over the last decade, there have been two major rival political parties, the TRT and the Democrats. Five out of seven governments were TRT or its incarnation (Palang Prachachon and Pheu Thai-led coalition governments) which contributed to UCS continuity. Despite the rivalry, the Surayud and Democrat governments also supported the UCS even before they came into power, as the scheme had proved financial risk protection to its members. The coup-appointed Surayud government (Figure 3), an antagonist to the Thaksin regime, not only “continued support to the UCS”, but under the leadership of Minister Mongkol Na Songkhla, “also took a number of bold steps” (KI 25, policy maker). These steps included the termination of the THB 30 co-payment in 2006 since the administrative cost of collecting the co-payment outweighed the revenue generated, deepening financial risk protection through introduction of universal Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT) for end-stage kidney patients in 2007, and Compulsory Licensing to improve access to high-cost medicines in 2006 to 2007.

Popular support because of tangible benefits helped ensure continued political commitment while NHSO’s significant operational capacity could translate political statements into tangible results. Moreover, civil society supported UCS co-payment termination since it brought it in line with the SHI and CSMBS.

“… Despite the rapid turnover [of governments], UCS has gained social support, free access to a functional district health service network not only improved utilization but also significantly reduced household out-of-pocket payment, from 33.1% of total health expenditure in 2001 to 13.9% in 2010 while government health expenditure increased from 56.3% to 74.8% of total health expenditure in the same period*. Realizing the tangible benefits, gradually it is the people who own the scheme, not the political party.” (KI 16, 18 policy makers).

*Thai Working Group on National Health Account. National Health Account 1994–2010. Nonthaburi, International Health Policy Program.

“… while politicians have set the agenda and direction, the technical arms of NHSB, such as the Finance and the Benefit Package subcommittees, have been able to introduce evidence into design and operation, while NHSO has had a high operational capacity to translate policy into effective implementation. This is possibly based on the low turnover in the intelligence function of NHSB (the two subcommittees) and the national health policy and systems research capacities”. (KI 13, policy maker; KI 15, implementer).

Tax-financed universal scheme: political promise and financial feasibility

Decisions on universality and a tax-financed UCS were inter-related and closely linked. KIs confirmed that political events contributed in a major way to decisions. During the election campaign in January 2001, TRT, convinced by technocrat reformists in the MOPH (including the founder SG and his team), adopted UCS as one of the top populist agendas, using “THB 30 for treatment of all diseases” as a campaign slogan, while the Democrats “insisted on a targeted approach” (KI 24, researcher). Subsequently, these technocrat reformists also played a critical role in influencing UCS policies.

In the 2001 election, TRT won half of the parliamentary seats, Democrats 26%, and other small- to medium-sized parties each 3% to 8%. Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra appointed Sudarat Keyuraphan and Surapong Suebwonglee as Health Minister and Deputy, to lead the UCS. Surapong and Sanguan, the then NHSO SG, shared a similar rural district doctor background and were alumni of the same medical school. Not only close colleagues, they were like-minded public health professionals, driven by personal experience of the value of the rural district health system.

TRT was bound to its manifesto, and not only was collecting a premium from UCS members who were mostly engaged in the rural informal economy technically not possible, it was not politically palatable [15]. When the total estimated resource requirements for universal coverage, THB 56.5 billion, was matched with the MOPH pooled budget for health services of THB 26.5 billion, the Prime Minister had the leadership ability and capacity to mobilize the shortfall of THB 30 billion from tax funding.

The closed-end provider payment method adopted by the UCS, namely capitation for outpatient services, and global budget and Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) for inpatient services, facilitated the political decision; it ensured a cap on expenditure.

“… To keep political promises and [fill] a feasible financial gap of THB 30 billion, it is most feasible to adopt a tax financed non-contributory universal programme. Collecting premium from UCS members was neither technically feasible in the short run nor politically palatable. A hard budget (where expenditure does not exceed the budget) as the result of applying closed-end provider payment such as capitation and case-based payment strongly supported the political decision. I think political context and technical evidence matter.” (KI 18, policy maker).

Reflections from other key informants indicated that translating political promises into actions was the top priority; it was considered almost impossible for a contributory scheme, given 75% of the population were in the informal sector, to reach universal coverage within the government’s four-year term. The only choice was a tax-financed scheme, given the capacities to mobilize additional tax finance and contain costs to ensure fiscal sustainability.

KIs noted that in 2001 to 2002, there was no significant opposition to adopting universality, it was socially and politically legitimate according to the Constitutional right to healthcare [16] and “government social responsibilities” (KI 07, human rights activist), nor was there opposition on general tax finance:

“Opposition to universality and tax finance seemed to be the minority; there was neither a coalition of opposition nor effective interface of opponents with political decisions.” (KI 24, researcher).

However, there were a few conservatives favouring targeting:

“I don’t understand why UCS should cover the rich who should pay for their own health, tax revenue should be used by the poor; when services are free, the rich will crowd out services. Targeted approach should be my principle.” (KI 03, academic).

A few international experts also disagreed with universality, on the grounds that fiscal space was too small since the economy had not yet fully recovered from the 1997 Asian economic crisis and it was also feared that hospitals would go bankrupt. Some experts advised against closed-end payment, advocating consumer choice of healthcare providers based on fee for service. However, capitation contracted model applied by SHI has contained cost in the long run with a decent quality of care [17].

“They (hospitals) would be viable when closed-end provider payment is applied. It was proved in SHI that capitation worked well since 1991.” (KI 25, policy maker).

The issue of whether SHI members should continue to contribute to their own scheme was discussed amongst civil society. The comprehensive Social Security Scheme includes cash benefit for sickness and maternity leave, funeral and invalidity grants, child allowance, unemployment benefits and pensions. Contribution to health benefit makes up only a small portion. In addition, once members are not covered by Social Security Scheme due to unemployment or retirement, they are automatically entitled to and benefit from the non-contributory UCS. A social consensus finally emerged that the contributory SHI scheme should be maintained.

Deepening financial risk protection: path dependence, civil society and NHSO capacities

All schemes prior to universal coverage had provided a comprehensive package, covering a wide range of services with an exclusion list such as treatment of infertility and aesthetic treatment or surgery. Path dependence, as well as pragmatism, meant that “UCS continued the comprehensive package approach” (KI 15, implementer).

De jure, almost all except a few negative list items are covered; de facto not all these services could be delivered due to constraints such as availability of specialists and medical devices at primary and secondary levels, or lack of incentives for hospitals to provide covered services such as cataract surgery. This resulted in either queues or patients choosing not to use their UCS entitlement but rather pay for private services. The Benefit Package sub-committee has recognized and removed bottlenecks within the existing package while at the same time responding to requests by Royal Colleges and specialists to include new expensive interventions into the benefit package through strict health technology assessment [18].

Reflections from various key informants suggest that the NHSO had developed purchasing skills, in the context of a single purchaser and competitive multiple sellers, negotiating for the lowest possible price given assured quality, resulting in cost savings. Cost savings provided more fiscal space to incorporate additional high cost but effective services into the benefit package. Adding new interventions into the UCS benefit package was guided by evidence of cost effectiveness, equity considerations, and budget impact assessment. For example, the NHSO outsourced open heart surgery and coronary artery bypass grafting to private hospitals with spare capacity [6]; and boosted cataract surgery by unbundling it from the DRG system and “providing an attractive fee schedule and incentives to physicians” (KI 10, implementer). It also used its monopsonistic power to obtain cost savings through central purchasing of quality assured medicines and medical devices, improving technical efficiency.

“NHSO negotiates price of haemodialysis down from US$ 67 to US$ 50 per session, with a million sessions a year, cost saving was as large as US$ 170 million. Centrally purchased erythropoietin drugs brings price down from US$ 21 to US$ 8 per vial, resulting in US$ 12 million annual cost saving.” (KI 05, implementer; KI 18, policy maker).

RRT was initially excluded from the UCS benefit package due to its high cost [19]. However, dialysis was provided free to CSMBS and SHI members, and had catastrophic costs for UCS members [20]. The issues were heavily analysed over several years, including demand estimates [21], cost effectiveness analysis [22], policy analysis [23] and a public opinion survey [24]. It was clear that RRT was not cost-effective and the long-term fiscal impact would be huge [25], especially given increasing prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, two major causes of kidney failure. However, universal RRT would protect households from catastrophic expenditure and promote equity across all schemes using public resources.

Under the leadership of Minister Mongkol Na Songkhla and pressure on principles of equity from the patient group [26], a Cabinet Resolution in 2007 endorsed universal RRT. No resistance was observed “though the policy had long-term fiscal implications” (KI 09, policy maker). The political decision was clearly made to protect households from catastrophic costs, with a strong sense of “rule of rescue” [27], and an ethical concern to ensure equity across the three health insurance schemes. The provision of evidence was also important.

Annual budget exercise: evidence based negotiation on a level field

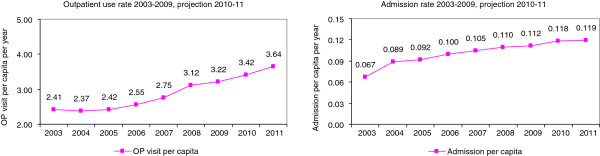

The UCS budget increased from THB 1,202 per member in 2002 to THB 2,693 in 2011, more than a two-fold increase (Figure 3), which was driven by increases in the outpatient and inpatient utilization rates (Figure 4), and costs of production resulting from 6% to 8% annual salary adjustments, drugs and medical supplies inflation, and extension of the benefit package, notably to anti-retroviral medicines in 2003, and RRT in 2007.

Figure 4.

Service utilization rate 2003–2011. Source: Health and Welfare Survey 2003–2007 and NHSO dataset for 2008–2011.

There were significant changes in budgeting for the health sector after the advent of UCS. Prior to 2001, the Bureau of Budget held discretionary power in allocating budgets to the MOPH, as they were negotiated on an individual programme basis and there were thousands of programmes and projects per year. Such discretionary power at times led to accusations of corruption. The new system was more transparent.

“After the advent of UCS, health service budget approval is based on per capita basis, estimated from utilization rates and unit cost. New budgeting system furnishes an evidence-based level negotiation field and curtails the discretionary power (of the Bureau of Budget). For example, a total NHSO budget of THB 117.4 billion in 2010 was the product of THB 2,497 per capita multiplied by 47 million members in 2010. The spill-over effect was seen when the Ministry of Education applied budgeting per pupil.” (KI 24, researcher).

The budget process is not only a “series of serious discussions” (KI 18, policy maker) between the Bureau of Budget and the Financing subcommittee, it has been made a “public issue” (KI 18, policy maker) gradually creating public ownership when the media monitored the budget discussions, and civil society held the government accountable to use evidence. Utilization rates and unit costs are undeniable facts. Making the budget a public issue was a key strategy ensuring sustainable financing of UCS.

Conclusions

Studies such as these explore complex processes that require careful interpretation. Some of the authors have been heavily involved in the evolution of universal coverage and perhaps because of this it was not easy to identify and solicit from KIs opposing views to the UCS design features. This may mean the study had a positive bias. In order to address this, findings from interviews were verified and triangulated carefully with written sources.

Policy processes are likely to be highly context-specific, but by elaborating the Thai experience in this paper, it is hoped that other countries can identify useful lessons from the management of the process. In Thailand, the political commitment to universal coverage and financial feasibility triggered the decision of a tax-financed UCS rather than targeting of subsidies and individual contributions. The operational capacity of the NHSO, guided by evidence and pressured by the civil society concerned about equity and financial protection, contributed to deepening financial risk protection and benefiting members. Gradually, the UCS has become owned by its members (75% of the population) and is less subject to political changes, though continued political support is vital. Budget proposals based on evidence of cost and utilization have furnished a level ground for negotiation on quantifiable indicators. The new transparent budgeting approach of UCS limits discretionary power and has replaced supply side-line item budgeting. Lessons for other countries include the importance of consistent political support, evidence informed decisions, and a capable purchaser organization.

Public expenditure on health, now at 12.7% of the annual government budget, is of concern, although less than 4% of GDP is spent on health. Continued research is needed on long-term financial sustainability, especially in the context of a rapidly ageing society and technological progress. However, research should also continue on the processes of universal coverage development, to learn how the new institutional arrangements become embedded in Thai politics and society and how they evolve in the longer term.

Future success of the Thai UCS will require coverage of effective interventions, which address primary and secondary prevention of non-communicable diseases in view of the rapid epidemiologic transition. These interventions often lie outside the health territory, such as effective control of tobacco and alcohol use, and community based interventions to prevent obesity and support active physical activities. In view of the demographic transition, Thailand needs effective long-term care policies, as elderly care occupies a large part of acute hospital services.

Abbreviations

CSBMS: Civil servant medical benefit scheme; GDP: Gross domestic product; KI: Key informants; MOPH: Ministry of public health; NHSB: National health security board; NHSO: National health security office; RRT: Renal replacement therapy; SG: Secretary general; SHI: Social health insurance; THB: Thai baht; TRT: Thai Rak Thai party; UCS: Universal coverage scheme.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

VT and SP developed the study protocol and conceptual approach, and conducted the study together with WP, PP, HS and JT. WP and SP led the analysis. VT synthesized the manuscript. AM is the advisor and guarantor of the study ensuring scientific rigour and contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Viroj Tangcharoensathien, Email: viroj@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Siriwan Pitayarangsarit, Email: siriwan@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Walaiporn Patcharanarumol, Email: walaiporn@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Phusit Prakongsai, Email: phusit@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Hathaichanok Sumalee, Email: hathaichanok@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Jiraboon Tosanguan, Email: jiraboon@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Anne Mills, Email: anne.mills@lshtm.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that this study is financially and technically supported by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO. We also wish to acknowledge the inputs of the Health Systems Financing Department, WHO and the late Dr Guy Carrin, in particular.

References

- Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Ir P, Aljunid SM, Mukti AG, Akkhavong K, Banzon E, Huong DB, Thabrany H, Mills A. Health-financing reforms in southeast Asia: challenges in achieving universal coverage. Lancet. 2011;377:863–873. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W, Jongudomsuk P. In: Building Decent Societies: Rethinking the Role of Social Security in Development. Townsend P, editor. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan; 2009. From targeting to Universality: lessons from the health system in Thailand; pp. 310–322. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P, Patcharanarumol W, Jongudomsuk P. ILO, GTZ, and WHO: Extending social protection in health: developing countries' experiences, lessons learnt and recommendations. Frankfurt: VAS; 2007. Universal Coverage in Thailand: the respective roles of social health insurance and tax-based financing; pp. 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Wibulpholprasert S, Nitayaramphong S. Knowledge-based changes to health systems: the Thai experience in policy development. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:750–756. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Swasdiworn W, Jongudomsuk P, Srithamrongswat S, Patcharanarumol W, Prakongsai P, Thammatach-Aree J. World Health Report 2010: Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Universal coverage scheme in Thailand: equity outcomes and future agendas to meet challenges (World Health Report 2010: Background Paper, 43) [Google Scholar]

- Prakongsai P, Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V. The equity impact of the universal coverage policy: lessons from Thailand. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2009;21:57–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakongsai P. The Impact of the Universal Coverage Policy on Equity of the Thai Health Care System. University of London: Doctoral thesis London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Tisayathicom K, Boonyapaisarncharoen T, Prakongsai P. Why has the Universal Coverage Scheme in Thailand Achieved a Pro-poor Public Subsidy for Health Care? Nonthaburi: Ministry of Public Health, International Health Policy Program; 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans TG, Chowdhury MR, Evans DB, Fidler AH, Lindelow M, Mills A, Scheil-Adlung X. Thailand’s Universal Coverage Scheme: Achievements and Challenges. An Independent Assessment of the First 10 Years (2001–2010) Health Insurance System Research Office: Nonthaburi; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P. Catastrophic and poverty impacts of health payments: results from national household surveys in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:600–606. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.033720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitayarangsarit S. The Introduction of the Universal Coverage of Health Care Policy in Thailand: Policy Responses. London: Doctoral thesis London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Walt G. Health Policy: An Introduction to Process and Power. London: Zed Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D. In: Comparing Policy Networks. Marsh D, editor. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1998. The development of the policy network approach. [Google Scholar]

- Rindle M, Thomas J. Public Choices and Policy Change: The Political Economy of Reform in Developing Countries. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pitayarangsarit S, Jongudomsuk P, Sakulpnich T, Singhapen S, Homhual P. In: From Policy to Implementation: Historical events during 2001-2004 of Universal Coverage in Thailand. Tangcharoensathien V, Jongudomsuk P, editor. Nonthaburi: International Health Policy Program; 2005. Policy formulation process (Chapter II) [Google Scholar]

- Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand BE 2550. 2007. http://www.senate.go.th/th_senate/English/constitution2007.pdf Accessed 12 January 2012.

- Mills A, Bennett S, Siriwanarangsun P, Tangcharoensathien V. The response of providers to capitation payment: a case-study from Thailand. Health Policy. 2000;51:163–180. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongudomsuk P, Limwattananon S, Prakongsai P, Srithamrongsawat S, Pachanee K, Mohara A, Patcharanarumol W, Tangcharoensathien V. In: The Economics of Public Health Care Reform in Advanced and Emerging Economies. Clements B, Coady D, Gupta S, editor. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund; 2012. Evidence-based health financing reform: the case of Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Kasemsup V, Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V. Budget impact analysis of a policy on universal access to RRT under universal coverage in Thailand. J Nephrol Soc Thailand. 2006;12(Suppl 2):136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Prakongsai P, Palmer N, Uay-Trakul P, Tangcharoensathien V, Mills A. What Happened to Poorer Thai Households when Renal Replacement Therapy was Excluded from the National Benefit Package? Nonthaburi: International Health Policy Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kasemsup V, Teerawattananon Y, Tangcharoensathien V. An estimate of demand for RRT under universal healthcare coverage in Thailand. J Nephrol Soc Thailand. 2006;12(Suppl 2):125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Teerawattananon Y, Mugford M, Tangcharoensathien V. Economic evaluation of palliative management versus peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease: evidence for coverage decisions in Thailand. Value Health. 2007;10(1):61–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V, Kasemsup V, Teerawattananon Y, Supaporn T, Vasavid C. Policy recommendation on universal access to renal replacement therapy under universal coverage in Thailand. J Nephrol Soc Thailand. 2006;12(Suppl 2):37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Vasavid C, Kasemsup V. An opinion poll on universal access to RRT under UC in Thailand. J Nephrol Soc Thailand. 2006;12(Suppl 2):21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Kasemsup V, Teerawattananon Y, Supaporn T, Chitpranee V, Prakongsai P. Universal Access to Renal Replacement Therapy in Thailand: A Policy Analysis. Nonthaburi: International Health Policy Program & Nephrology Society of Thailand; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet was requested to approve a gold card for kidney failure therapy. 2012. http://prachatai.com/node/14458/talk Accessed 2 February 2012.

- McKie J, Richardson J. The rule of rescue. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2407–2419. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]