Summary

This report describes the implementation of a pilot patient navigation (PN) program created to address cervical cancer disparities in a predominantly Hispanic agricultural community. Since November 2009, a patient navigator has provided services to patients of Catholic Mobile Medical Services (CMMS). The PN program has resulted in the need for additional clinic sessions to accommodate the demand for preventive care at CMMS.

Keywords: Patient navigation, Hispanic women, cervical cancer, cancer disparities, farmworkers, cervical cancer screening

Hispanic farmworkers in the United States are at higher risk for cervical cancer (CC) and experience higher CC mortality rates than the general U.S. population.1–3 Such disparities are the result of a complex interplay of factors, including low socioeconomic status and social injustice, combined with language, literacy, and knowledge barriers.4–14 Specific barriers to cervical cancer care among Latina migrant workers in the United States include lack of awareness of the importance of screening, cultural beliefs, cost, lack of health insurance, lack of transportation, and child care difficulties.15

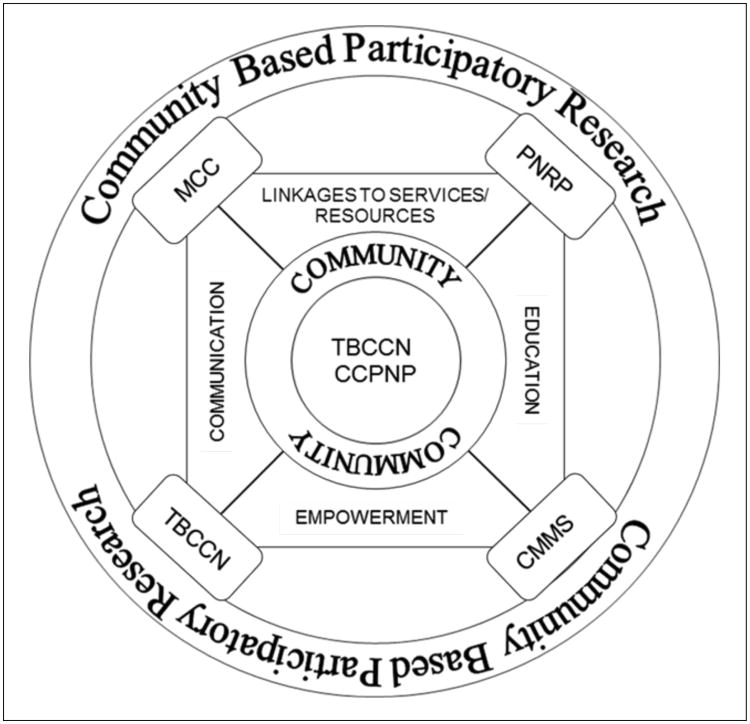

To understand disparities in CC incidence and mortality, there is a need to understand better circumstances in which they occur.11 In Florida, Hispanics (and specifically Mexican women) have a higher incidence of cervical cancer than non-Hispanic Whites.16 The setting of this pilot patient navigator project is rural, Eastern Hillsborough County, Florida. County-wide estimates for 2010 indicate that 56.6% of women age 18 years or older in Hillsborough County had a Pap test within the past year.17 The rural area of Hillsborough County is home to a large population of residents who work in occupations related to agriculture, and whose health needs are addressed in part by a faith-based health care organization, Catholic Mobile Medical Services (CMMS; Figure 1). Our approach to addressing CC disparities drew from established resources and expertise of two National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded initiatives, the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network (TBCCN) program18 and the Moffitt Cancer Center Patient Navigation Research Program (Moffitt PNRP).19 This field action report describes the conceptualization, implementation, and ongoing evaluation of the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network Cervical Cancer Patient Navigation Program (TBCCN-CCPNP).

Figure 1.

Development of the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network Cervical Cancer Patient Navigator Program.

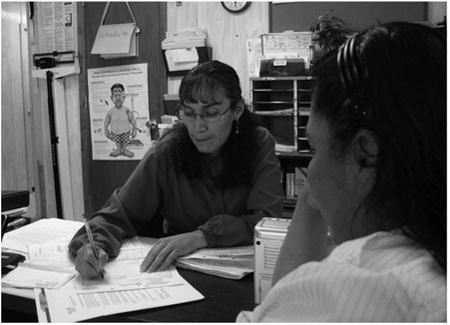

The patient navigator assists a patient at Catholic Mobile Medical Services.

Program Description

Patient navigation (PN) is designed to reduce health care disparities by assisting patients in overcoming barriers to high-quality care for a health condition.20,21 Two projects (TBCCN and Moffitt PRNP) informed the development of the TBCCN-CCPNP. The existing TBCCN infrastructure consists of a 22-member community network program. The partnership between TBCCN and one of their longstanding partners, CMMS, was expanded to create the TBCCN-CCPNP. The TBCCN aims to address critical access, prevention and control issues that affect medically underserved, low-literacy, and low-income populations in selected areas of Hillsborough, Pinellas, and Pasco Counties. Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network provided the infrastructure through which the TBCCN-CCPNP was created and implemented. Catholic Mobile Medical Services has had a formal partnership with TBCCN since 2005 when the TBCCN network was created. The partnership is formally defined in a memorandum of understanding and involves a mutually beneficial exchange of expertise and resources. Sponsored through Catholic Charities and the Diocese of St. Petersburg, Florida, CMMS provides primary care services through evening mission-based clinics and a mobile van delivering care at health fairs, missions, and migrant camps in Hillsborough County. The Moffitt PNRP is one of nine sites funded by NCI and the American Cancer Society to evaluate efficacy of PN in reducing time from screening abnormality to diagnostic resolution and time from cancer diagnosis to initiation of cancer treatment for primary care patients who received a screening abnormality suspicious for breast or colorectal cancer.19–22

In 2009, through American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funding, and building on the strong collaborative relationship between CMMS, TBCCN, and Moffitt PNRP, the TBCCN-CCPNP was created to improve CC care and screening for rural Hispanic migrant farmworker women at CMMS. Prior to TBCCN-CCPNP, CMMS reported three main gaps in CC care: (1) delays in reporting Pap test results; (2) lack of coordination of follow-up care for patients with abnormal findings; and (3) lack of education about CC and human papillomavirus (HPV).23

A lay bilingual patient navigator was identified by the director of CMMS, interviewed by TBCCN staff, and hired in November 2009. The patient navigator had lived in the community for 13 years and had worked at a nearby faith-based social service organization as a teacher's aide and a social worker. The navigator received three months of training by Moffitt Cancer Center and CMMS personnel based on the PNRP model.24 While there are a number of PN models, including professional PN models (e.g., nurses, social workers), lay PN models, or models that combine both professional and lay PN,21 a lay PN model was selected for the TBCCN-CCPNP. Similar to the Moffitt PNRP,19 a lay PN model was selected based on program needs identified by CMMS and the fact that most of the responsibilities of the patient navigator involved providing assistance with outreach and assisting patients in obtaining Pap tests. The patient navigator has significant support from a parish nurse, a physician's assistant, and a team of other health care providers and health education professionals.25 At the start of TBCCN-CCPNP, the project team created a low-literacy patient navigator-delivered CC and HPV educational intervention based on formative research conducted with the target population and Social Cognitive Theory.26 The bilingual lay patient navigator was instrumental in the creation of this educational intervention and ensured its cultural and linguistic relevance through the use of terminology familiar to community members and by addressing culturally-specific outcome expectations identified in formative research, such as concerns about pain. The educational intervention consists of oral, small-group or individual question and answer sessions. It is provided to women in either English or Spanish in the busy clinic setting and at community events. Examples of education questions include: “What if I am embarrassed during the Pap?” and “What is HPV?” The educational intervention is undergoing revisions based on learner verification interviews conducted with members of the community of rural Hispanics and informal feedback from health care providers who serve this population. A pilot test of these materials is planned for the future.

In addition to providing education, the TBCCN-CCPNP patient navigator performs the following services: (1) scheduling, reminding, and rescheduling patients for CC screening and diagnostic testing following abnormal Pap tests; (2) coordinating care of women who have received abnormal Pap test results; (3) accompanying women to specialty care appointments; (4) ensuring women receive Pap test results; and (5) facilitating new patient appointments for women in the community.

Discussion and Evaluation

Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network-CCPNP is being evaluated using both process and outcome evaluation methods developed by TBCCN staff in direct collaboration with our community partner (CMMS). Process evaluation focuses on tracking services provided by the patient navigator including: (1) number of educational sessions; (2) number of women notified regarding Pap test results; (3) number of women provided follow-up services for an abnormal Pap test; and (4) number and type of actions taken to overcome barriers for patients needing follow-up services. Outcome measures include time to notify women of both normal and abnormal Pap test results, and adherence to all recommended follow-up care following an abnormal Pap test. Evaluation of these two outcomes is conducted through a pre-post research design comparing outcomes measured in the year prior to implementation of TBCCN-CCPNP and in the year during implementation of the TBCCN-CCPNP. Recruitment of participants into the TBCCN-CCPNP outcome evaluation was limited to female patients 18 years or older who received medical care either through the CMMS stationary clinic or the CMMS mobile unit operating at various local health fairs. These outcome data have been collected, are currently being analyzed, and will be presented in another paper.

Process data collected by clinical tracking and outreach forms indicate that since November 2009, the PN has had 996 documented patient encounters and has coordinated follow-up care of patients with abnormal Pap test results, including close follow-up of patients identified in need of specialty care. The primary service offered by the navigator has been enhancing communication between the clinic and the patients (i.e., making calls to schedule, reschedule, and remind patients about appointments). Most patients served by the program have been Hispanic Spanish-speakers, with low levels of education and low incomes. Since implementing TBCCN-CCPNP, 177 women have received Pap tests largely due to the patient navigator's communication and outreach efforts. The CMMS clinic has expanded monthly clinic hours to accommodate numerous new patients requesting cervical screening who were identified by the patient navigator. CMMS has also added a colposcopy clinic to meet the needs of some women with abnormal Pap tests.

Partnerships between community and academic organizations are crucial to address cancer disparities.18 Working through an established community network program partnership and drawing on expertise of a large PN program, the TBCCN-CCPNP was efficiently implemented. Although evaluation is still ongoing, TBCCN-CCPNP is working to address needs identified by our community partner, CMMS. Findings from this pilot will generate new knowledge about evidence-based PN programs in community-based settings and offer a solution to help ameliorate CC disparities.

Next Steps

Future directions include completing the evaluation, modifying educational materials, and conducting a larger scale study on the efficacy of the PN model. TBCCN-CCPNP is currently seeking additional funding to sustain project activities and expand upon the educational component of the program.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms. Natalia Lopez for her assistance in transcribing indepth interviews. The Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network (U01CA114627; U54CA153509) and Moffitt Cancer Center Patient Navigation Research Program (U01 CA117281) are funded by the Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities at the National Cancer Institute. Catholic Mobile Medical Services is a division of Catholic Charities and is funded by the Diocese of St. Petersburg, Florida.

Notes

- 1.Mills PK, Beaumont JJ, Nasseri K. Proportionate mortality among current and former members of the United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO, in California 1973–2000. J Agromedicine. 2006;11(1):39–48. doi: 10.1300/J096v11n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills PK, Dodge J, Yang R. Cancer in migrant and seasonal hired farm workers. J Agromedicine. 2009;14(2):185–91. doi: 10.1080/10599240902824034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills PK, Kwong S. Cancer incidence in the United Farmworkers of America (UFW), 1987–1997. Am J Ind Med. 2001 Nov;40(5):596–603. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarinci IC, Beech BM, Kovach KW, et al. An examination of sociocultural factors associated with cervical cancer screening among low-income Latina immigrants of reproductive age. J Immigr Health. 2003 Jul;5(3):119–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1023939801991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitkopf CR, Pearson HC, Breitkopf DM. Poor knowledge regarding the Pap test among low-income women undergoing routine screening. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005 Jun;37(2):78–84. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.078.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd TL, Chavez R, Wilson KM. Barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer screening among Hispanic women. Ethn Dis. 2007 Winter;17(1):129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez ME, Diamond PM, Rakowski W, et al. Development and validation of a cervical cancer screening self-efficacy scale for low-income Mexican American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 Mar;18(3):866–75. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harmon MP, Castro FG, Coe K. Acculturation and cervical cancer: knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors of Hispanic women. Women Health. 1996;24(3):37–57. doi: 10.1300/j013v24n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim JW. Linguistic and ethnic disparities in breast and cervical cancer screening and health risk behaviors among Latina and Asian American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010 Jun;19(6):1097–107. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMullin JM, De Alba I, Chavez LR, et al. Influence of beliefs about cervical cancer etiology on Pap smear use among Latina immigrants. Ethn Health. 2005 Feb;10(1):3–18. doi: 10.1080/1355785052000323001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otero-Sabogal R, Stewart S, Sabogal F, et al. Access and attitudinal factors related to breast and cervical cancer rescreening: why are Latinas still underscreened? Health Educ Behav. 2003 Jun;30(3):337–59. doi: 10.1177/1090198103030003008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanslyke JG, Baum J, Plaza V, et al. HPV and cervical cancer testing and prevention: knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes among Hispanic women. Qual Health Res. 2008 May;18(5):584–96. doi: 10.1177/1049732308315734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramirez AG, Suarez L, Laufman L, et al. Hispanic women's breast and cervical cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 2000 May-Jun;14(5):292–300. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.5.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suarez L, Roche RA, Nichols D, et al. Knowledge, behavior, and fears concerning breast and cervical cancer among older low-income Mexican-American women. Am J Prev Med. 1997 Mar-Apr;13(2):137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coughlin SS, Richards TB, Nasseri K, et al. Cervical cancer incidence in the United States in the U.S.-Mexico border region, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008 Nov;113(10 Suppl):2964–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinheiro PS, Sherman RL, Trapido EJ, et al. Cancer incidence in first generation U.S. Hispanics: Cubans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and new Latinos. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 Aug;18(8):2162–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Florida Department of Health. Florida charts: community health assessment research tool set, Florida behavioral risk factor data. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Department of Health; Available at: http://www.foridacharts.com/charts/brfss.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meade CD, Menard JM, Luque JS, et al. Creating community-academic partnerships for cancer disparities research and health promotion. Health Promot Pract. 12(3):456–62. doi: 10.1177/1524839909341035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells KJ, Meade CD, Calcano E, et al. Innovative approaches to reducing cancer health disparities: the Moffitt Cancer Center Patient Navigator Research Program. J Cancer Educ. 2011 Dec;26(4):649–57. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0238-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011 Jul-Aug;61(4):237–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008 Oct 15;113(8):1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008 Dec;113(12):3391–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luque JS, Tyson DM, Markossian T, et al. Increasing cervical cancer screening in a Hispanic migrant farmworker community through faith-based clinical outreach. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2011 Jul;15(3):200–4. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318206004a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calhoun EA, Whitley EM, Esparza A, et al. A national patient navigator training program. Health Promot Pract. 2010 Mar;11(2):205–15. doi: 10.1177/1524839908323521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011 Aug;117(15 Suppl):3539–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]