Abstract

We compared pre- to post-pregnancy change in weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, diet and physical activity in women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Using the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study we identified women with at least one pregnancy during 20 years of follow-up (n=1,488 with 3,125 pregnancies). We used linear regression with generalized estimating equations to compare pre- to post-pregnancy changes in health behaviors and anthropometric measurements between 137 GDM pregnancies and 1,637 non GDM pregnancies, adjusted for parity, age at delivery, outcome measure at the pre-pregnancy exam, race, education, mode of delivery, and interval between delivery and post-pregnancy examination.

Compared with women without GDM in pregnancy, women with GDM had higher pre-pregnancy mean weight (158.3 vs. 149.6 lb, p=0.011) and BMI (26.7 vs. 25.1 kg/m2, p=0.002), but non-significantly lower total daily caloric intake and similar levels of physical activity. Both GDM and non GDM groups had higher average postpartum weight of 7–8 lbs and decreased physical activity on average 1.4 years after pregnancy. Both groups similarly increased total caloric intake but reduced fast food frequency. Pre- to post- pregnancy changes in body weight, BMI, waist circumference, physical activity and diet did not differ between women with and without GDM in pregnancy.

Following pregnancy women with and without GDM increased caloric intake, BMI and weight, decreased physical activity, but reduced their frequency of eating fast food. Given these trends, postpartum lifestyle interventions, particularly for women with GDM, are needed to reduce obesity and diabetes risk.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) complicates about seven percent of pregnancies in the U.S., depending on the population studied (1). Women with a history of GDM are at high risk for type 2 diabetes (2, 3), with 3.7% diagnosed by nine months after delivery and 19% by nine years after delivery, within a large Canadian health care system (4). Because of this increased risk, experts and national organizations are calling for increased screening, monitoring and promotion of lifestyle changes for diabetes prevention (5, 6). In addition to triggering increased provider surveillance, a diagnosis of GDM could heighten women’s awareness of diabetes risk and motivate healthy behavioral change. However, support for making these lifestyle changes is crucial. Lifestyle interventions, such as The Diabetes Prevention Program, may reduce diabetes incidence in women with GDM histories (7).

Cross-sectional studies show that providers may not adequately inform patients of their diabetes risk (8, 9), women may fail to perceive themselves at risk for diabetes (10) and overall, at-risk women are not engaging in healthier lifestyles (11, 12). A recent prospective cohort followed 238 Canadian women with and without GDM for one year postpartum (13). They reported no differences at one year in work or sports-related physical activity between groups, but women with GDM reported increased leisure-time physical activity at one year compared to women without GDM (13). However, few studies have measured weight and health behaviors from before to after pregnancy in women with GDM to assess post-pregnancy changes, although one previous study reported less than a two kg difference in mean weight gain from before to after pregnancies among women with and without GDM pregnancies (3).

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study is a prospective cohort study of young men and women with more than 20 years of follow up. Our objective was to compare changes in health behaviors (dietary intake and physical activity), and anthropometric measures (weight, body mass index [BMI] and waist circumference) from before to several years after pregnancy in women with and without GDM. We hypothesized that a diagnosis of GDM, despite its potential role as a “prognostic sign” for diabetes would not be associated with improved post-pregnancy anthropometric measures or health behaviors (e.g. less weight gain, improved diet). Understanding post-pregnancy changes in women with GDM could inform interventions aimed at promoting healthy post-pregnancy behavior changes.

Research Design and Methods

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study

The CARDIA Study is a multicenter, longitudinal, cohort study examining determinants of cardiovascular disease among black and white young adults. In 1985–86, baseline examinations were performed on 5,115 participants (50% of eligible persons) aged 18–30 years, of whom 54% were women, 52% were black and 48% were white. They were recruited from four geographic areas in the United States: Birmingham, Alabama; Chicago, Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Oakland, California. For this analysis we used data from participants who were followed up for 20 years with seven clinical examinations: 1985–86 (baseline), 1987–88 (year two), 1990–91 (year five), 1992–93 (year seven), 1995–96 (year 10), 2000–01 (year 15), 2005–6 (year 20). At year 20 the retention rate was 71.8% and 87.5% for completion of the in-person examination and telephone interview, respectively (14). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. Details of the study design, methodology, and cohort characteristics have been reported elsewhere (15, 16).

Sample selection

For this analysis we included females with at least one pregnancy during the 20 years of follow-up. We excluded pregnancies reported in duplicate, classified as abortions, tubal pregnancies or miscarriages, or if information about the pregnancy was incomplete (e.g. missing delivery date or mode). For the main analysis using anthropometric and physical activity outcomes, we excluded pregnancies if the participant’s pre-pregnancy CARDIA examination occurred more than five years before the post-pregnancy CARDIA examination to improve its validity as representative of post-pregnancy change.

Because dietary intake was assessed more than five years apart (baseline and year 7), we included all pregnancies that had occurred between the baseline and year seven examinations for the dietary outcomes.

Data collection

Definition of GDM and pregnancy related variables

At each CARDIA examination, women reported the number of interim pregnancies, including abortions, miscarriages, and live births or stillbirths with delivery dates, length of gestation, and whether they were currently pregnant. Using a method previously described by Gunderson et al. (3) we selected pregnancies with at least 20 weeks gestation that resulted in a live birth. At each CARDIA examination, women reported having been diagnosed with diabetes or diabetes that occurred only during pregnancy since the previous exam (3). We assigned GDM status for each interim pregnancy based on self-report and absence of overt diabetes before conception. Self report of GDM was previously validated in a sub-sample of 165 CARDIA women by abstracting medical record data for their 200 births between baseline and year 10 (3). The sensitivity for self-reported GDM was 100% (20/20), and specificity was 92% (134/145) (3).

Outcomes: Anthropometric measures and health behaviors

Measurements of body weight, height and waist circumference were obtained at each examination according to a standardized protocol described previously (17, 18). BMI was computed as weight in kilograms divided by squared height in meters.

The CARDIA Physical Activity History was used to calculate moderate (e.g. taking walks), strenuous (e.g. bicycling), and total physical activity scores at each examination based on the frequency and duration of 13 different types of activities (19). The total physical activity score was calculated using a scoring algorithm (20) and then expressed in terms of “exercise units” with higher scores indicating greater amounts of exercise. The questionnaire has been externally validated using treadmill test performance, as well as compared with other physical activity questionnaires (21, 22). For reference, at baseline, 74% of CARDIA participants with a total physical activity score between 300–399 exercise units met exercise recommendations to perform “regular vigorous exercise” during the past six months (19). At the CARDIA baseline examination, black women reported on average 260 and white women reported on average 324 exercise units (19).

Dietary intake was collected at baseline and year seven using the validated interviewer administered CARDIA Diet History questionnaire, which assessed total daily caloric intake (kilocalories [kcal] per day), percentage of kilocalories from total fat and daily fiber intake (grams) (23, 24).

At baseline and examination years five and 10, participants were asked how often they eat in a fast food restaurant, which we reported as times per month (25).

Data were realigned from the CARDIA examination schedule to conform with pregnancy timing, so that one or more CARDIA examinations may have occurred prior to a given pregnancy. The pre-pregnancy outcome measures were assessed at the CARDIA examination immediately prior to the reported interim pregnancy and the post-pregnancy outcome measures were assessed at the examination as soon after the interim pregnancy. We calculated mean pre- and post-pregnancy values for the each of the outcomes: weight, BMI, waist circumference, total physical activity, and dietary measures. We determined the change in each value by subtracting the pre-pregnancy value from the post-pregnancy examination value. This procedure was followed for each pregnancy within each woman.

Other covariates

Sociodemographic, medical and family history, and behavioral characteristics (cigarette smoking, education, marital status, employment status) were assessed by self- and interviewer-administered questionnaires at the baseline CARDIA examination.

Statistical analysis

We conducted baseline and pre-pregnancy descriptive analyses to compare women with one or more GDM pregnancies (GDM history) with women who did not develop GDM in an interim pregnancy (No GDM history) during 20-years of follow-up using Student’s t-test for comparisons of means, Wilcoxon rank-sum test for comparisons of medians and Chi square for categorical variables.

We classified each pregnancy as GDM or non GDM. We used linear regression models with the generalized estimating equation (GEE) method to compare the pre- to post- pregnancy changes in each outcome in GDM versus non GDM pregnancies. We adjusted for parity, age at the time of delivery, pre-pregnancy outcome measure, race, education, mode of delivery, and interval between the delivery and post-pregnancy outcome measure. Because GEE accounted for correlations among multiple pregnancies by the same woman over time (26) we elected to adjust for overall parity, but not the number or order of GDM pregnancies in any given woman.

In addition, because health behaviors may differ by pre-pregnancy obesity and race, we conducted analyses stratified by pre-pregnancy BMI (< 30 and =≥30 kg/m2) and race (white and black).

We used STATA software version 11 (College Station, TX) (27) and a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics of women with and without a history of GDM

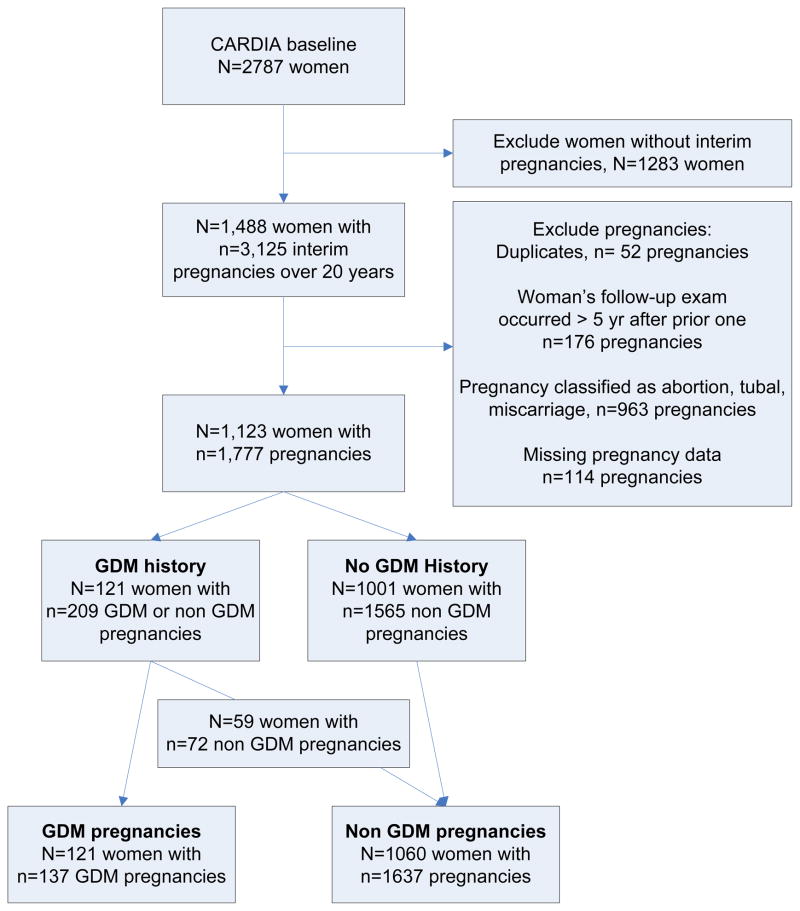

Figure one shows the selection of the sample of women with and without a history of GDM, and the associated number of GDM and non GDM pregnancies. We identified 1,488 women with 3,125 interim pregnancies during 20 years of the CARDIA study, with the 80% of pregnancies occurring in the first 10 years of the study. After exclusions, our final sample included 121 women with a history of GDM, who had 137 GDM and 72 non GDM pregnancies. 1,001 women without a history of GDM had 1,565 non GDM pregnancies. The final pregnancy analysis included 137 GDM pregnancies (from 121 women) and 1,637 non GDM pregnancies (from 59 women with GDM in a different pregnancy and 1,001 women without any GDM history).

Figure 1.

Flow of CARDIA sample selection of women with ≥1 GDM complicated pregnancies (GDM History) and their associated GDM and non GDM pregnancies

Table one shows baseline and pre-pregnancy characteristics comparing women with and without a GDM history during the 20 years of the CARDIA study. Women with a GDM history did not differ from those without a GDM history in terms of race, marital status, educational attainment or smoking status. Women with a GDM history had more interim births during CARDIA follow-up (mean 1.7 vs. 1.6, p=0.031), but had no difference in parity prior to CARDIA enrollment. Women with a GDM history were older at their first interim delivery (29.1 vs. 27.8 years, p-value=0.001), more likely to have a family history of diabetes (22.3% vs. 13.1%, p-value=0.006), had higher mean weight (158.1 vs. 147.3 lbs, p-value=0.011) and BMI (26.8 vs. 24.7, p=0.002) and were more likely to report being on a weight loss diet in the past (60.3% vs. 47.3%, p=0.007). However, women with a GDM history had a non-significantly lower total daily caloric intake (1879 vs. 2117 kcal/day, p-value=0.051) measured at the baseline exam. Total, strenuous or moderate physical activity scores from the baseline exam were not different between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women with and without a history of GDM over 20 years of follow-up

| Characteristic | GDM history N=121 | No GDM history N=1001 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at CARDIA baseline exam, years (SD) | 24.8 (3.8) | 24.3 (3.6) | 0.142 |

| Mean age at first interim delivery, years (SD) | 29.1 (4.1) | 27.8 (4.5) | 0.001 |

| Black (vs. white), n (%) | 54 (44.6%) | 511 (51.1%) | 0.182 |

| Married (vs. single), n (%) | 43 (35.8%) | 349 (34.9%) | 0.845 |

| ≤ High school diploma (vs. > high school), n (%) | 34 (28.1%) | 352 (35.2%) | 0.122 |

| Ever smoked (vs. never smoked), n (%) | 54 (44.6%) | 393 (39.3%) | 0.255 |

| History of diabetes in mother or father, n (%) | 27 (22.3%) | 131 (13.1%) | 0.006 |

| Mean number of pregnancies during 20 years of CARDIA follow-up examinations (SD) | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.7) | 0.031 |

| History of ≥ 1 pregnancy, prior to baseline exam, n (%) | 61 (50.4%) | 494 (49.3%) | 0.840 |

| Mean weight, lb (SD) | 158.1 (44.1) | 147.3 (34.7) | 0.011 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 26.8 (6.7) | 24.7 (5.6) | 0.002 |

| Median total daily caloric intake, kcal (IQR) | 1879 (1573–2554) | 2117 (1608–2888) | 0.051 |

| Median total physical activity score (IQR) | 236 (108–432) | 256 (129–431) | 0.480 |

| Median strenuous activity score (IQR) | 114 (29–266) | 133 (48–276) | 0.209 |

| Median moderate activity score (IQR) | 100 (36–186) | 96 (40–175) | 0.798 |

| Been on weight loss diet, n (%) | 73 (60.3%) | 472 (47.3%) | 0.007 |

| Mean number of times eating fast food per month (SD) | 8 (10) | 7 (7) | 0.136 |

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; GDM=gestational diabetes mellitus; IQR=interquartile range; SD=standard deviation

Comparison of pre-to-post anthropometric changes in GDM and non-GDM pregnancies

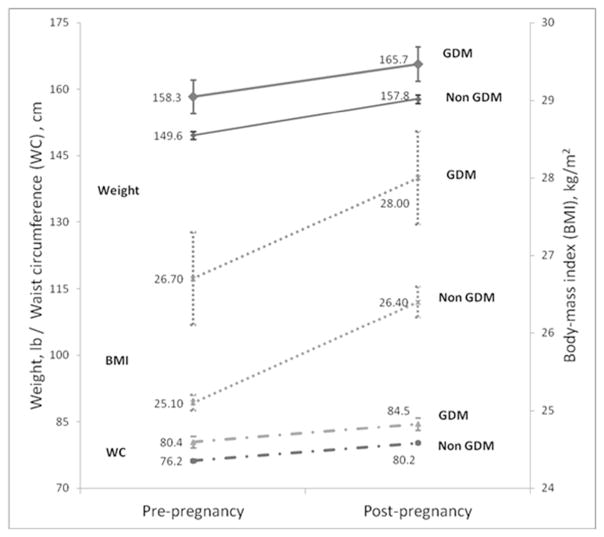

Table two shows the mean anthropometric measures prior to pregnancy, following pregnancy and the adjusted pre- to post- pregnancy changes, between the GDM and non GDM pregnancy groups. Compared with the non GDM pregnancy group, the GDM pregnancy group had higher pre- and post- pregnancy weights (pre-pregnancy mean of 158.3 vs. 149.6 lbs, respectively, and post-pregnancy mean of 165.7 vs. 157.8 lbs). However, the pre- to post- pregnancy weight change was not significantly different between the GDM and non GDM groups, after adjustment for age, race, education, parity, cesarean delivery and the delivery to post-pregnancy examination interval. Both groups similarly had a mean of 7–8 lbs of post-pregnancy weight retention after an average of 1.4 years (range: 0.4 to 5 years) following pregnancy.

Table 2.

Pre- to post-pregnancy changes in anthropometrics in GDM and non GDM pregnancies

| GDM pregnancy | Non GDM pregnancy | Difference | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n=137 | n=1637 | |||

| Weight (lb) | ||||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 158.3 (3.8) | 149.6 (0.9) | 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 165.7 (3.9) | 157.8 (1.0) | 5.3 | 0.007 |

| Adjusted change2 (95%CI) | 7.3 (6.9,7.7) | 8.2 (8.1,8.3) | −0.7 (−3.1,1.7) | 0.577 |

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 26.7 (0.6) | 25.1 (0.1) | 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 28.0 (0.6) | 26.4 (0.2) | 1.0 | 0.006 |

| Adjusted change2 (95%CI) | 1.2 (1.2,1.3) | 1.4 (1.3,1.4) | −0.07 (−0.5,0.3) | 0.745 |

|

| ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | ||||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 80.4 (1.2) | 76.2 (0.3) | 3.2 | <0.001 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 84.5 (1.3) | 80.2 (0.3) | 2.7 | 0.001 |

| Adjusted change2 (95%CI) | 4.0 (3.7,4.3) | 4.0 (3.9,4.1) | 0.4 (−0.6,1.5) | 0.427 |

Abbreviations: cm= centimeter; CI=confidence interval; kg= kilograms; lb= pounds; m=meters; SE= standard error

p-values calculated using linear regression with generalized estimating equations.

Adjusted for age, race, education, parity, cesarean delivery, interval between delivery and post pregnancy examination

Similar to weight, the GDM pregnancy group had elevated pre and post-pregnancy BMI and waist circumference compared to the non GDM group. However, the pre- to post- pregnancy changes in BMI and waist circumference were not significantly different between the GDM and non GDM groups, using the same covariate adjustments as the outcome of weight.

Figure two displays the weight, BMI and waist circumference trajectories pre- to post-pregnancy in the GDM and non GDM groups. Women in both groups increased weight, BMI and waist circumference pre- to post-pregnancy, with similar pre- to post-pregnancy changes.

Figure 2.

Mean pre- to post-pregnancy weight, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) in GDM and non GDM pregnancies

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; GDM=gestational diabetes mellitus; WC= waist circumference

Comparison of pre-to-post physical activity and diet changes in GDM and non-GDM pregnancies

Table three shows the health behavior measures prior to pregnancy, following pregnancy and the adjusted pre- to post- pregnancy changes, between the GDM and non GDM pregnancy groups. The GDM and non GDM pregnancy groups did not significantly differ in their pre- or post-pregnancy total physical activity scores. Both groups similarly decreased their mean total physical activity scores post-pregnancy, by 44.3 (95% CI: 20.0 to 68.5) points in the GDM group and 54.0 (95% CI: 46.8 to 61.3) points in the non GDM group, after an average of 1.4 years (range: 0.4 to 5 years) following pregnancy. The difference between the pre- to post pregnancy changes in physical activity in the GDM and non GDM pregnancy groups was not statistically significant. (Table three)

Table 3.

Pre- to post-pregnancy changes in physical activity score and dietary intake in GDM and non GDM pregnancies

| GDM pregnancy | Non GDM pregnancy | Difference | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARDIA total physical activity score | n=137 | n=1637 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 282.4 (19.4) | 290.0 (5.7) | −4.2 | 0.816 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 233.6 (21.2) | 235.9 (5.2) | 4.7 | 0.807 |

| Adjusted change3 (95%CI) | −44.3 (−68.5,−20.0) | −54.0 (−61.3,−46.8) | 4.6 (−30.9,−40.0) | 0.801 |

|

| ||||

| Daily caloric intake (kcal) | n=783 | n=9093 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 2174 (138) | 2350 (40) | −177 | 0.226 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 2418 (167) | 2509 (38) | −91 | 0.668 |

| Adjusted change2 (95%CI) | 245 (98,391) | 158 (118,199) | 28 (−349,406)) | 0.883 |

|

| ||||

| Percent calories from fat (%) | n=783 | n=9093 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 38.4 (0.7) | 37.8 (0.2) | 0.7 | 0.341 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 41.8 (2.3) | 41.8 (0.7) | 0.2 | 0.941 |

| Adjusted change2 (95%CI) | 3.3 (1.9,4.7) | 3.9 (3.4,4.2) | 1.0 (−4.0,6.0) | 0.700 |

|

| ||||

| Daily fiber intake (gm) | n=783 | n=9093 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 4.8 (0.3) | 5.0 (0.1) | −0.1 | 0.696 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 20.3 (1.1) | 20.6 (0.3) | −0.3 | 0.807 |

| Adjusted change2 (95%CI) | 15.6 (15.0,15.8) | 15.6 (15.5,15.7) | −0.3 (−2.6,2.1) | 0.828 |

|

| ||||

| Fast food frequency (times per month) | n=1124 | n=12834 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 7.9 (1.0) | 5.5 (0.2) | 2.0 | 0.014 |

| Post-pregnancy, mean (SE) | 5.8 (0.6) | 4.9 (0.2) | 0.6 | 0.277 |

| Adjusted change2 (95%CI) | −2.0 (−3.6,−0.5) | −0.6 (−0.9,−0.3) | 0.3 (−0.7,1.4) | 0.545 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; gm=grams; kcal=kilocalories; SE= standard error

p-values calculated using linear regression with generalized estimating equations.

Adjusted for age, race, education, parity, cesarean delivery, interval between delivery and post pregnancy examination;

For the analysis with the dietary intake outcomes (daily caloric intake, percent calories from fat, daily fiber intake) we included all pregnancies between baseline and examination year seven, enabling comparisons for 78 GDM and 909 non GDM pregnancies.

Fast food frequency was assessed at baseline and examination years five and ten enabling comparisons for 112 GDM and 1283 non GDM pregnancies.

Regarding dietary changes, both the GDM and non GDM groups increased in total daily caloric intake, percent calories from fat, and daily fiber intake on average 3.1 years (range: 0.1–7 years) after pregnancy. Both the GDM and non GDM groups slightly decreased their frequency of eating fast food on average 2.2 years after delivery (range: 0.04–5.5 years). The difference in the pre- to post-pregnancy dietary changes was not statistically different between the two groups. (Table three)

Additional analyses

We conducted additional separate analyses stratified by pre-pregnancy BMI and black vs. white race to determine if these factors modified the association between health behaviors and anthropometric changes following pregnancy among the GDM and non GDM pregnancy groups. These analyses confirmed the results between the two groups across pre-pregnancy BMI and race (data not shown).

Conclusions

This study describes pre- to post pregnancy anthropometric and health behavioral changes in a 20-year prospective cohort study of black and white women of childbearing age. Compared with women without GDM, women with GDM had higher pre-pregnancy weight, BMI, but similar levels of physical activity. However, we found similar pre- to post-pregnancy changes for GDM and non GDM pregnancies, including increased weight, BMI and waist circumference, which are known risk factors for progression to type 2 diabetes (28). Following pregnancy, regardless of GDM status, women similarly decreased physical activity, increased caloric intake, including fiber intake, but reduced fast food frequency.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine pre- to post-pregnancy weight and diet changes in women with and without GDM. Using the CARDIA Study, Gunderson and colleagues previously reported 15.9 kg and 14.3 kg of total weight gain from the baseline to 20 year examinations in women with and without GDM histories, respectively (3). We confirmed post-pregnancy weight gain in both groups, without a statistically significant difference between them, although women with GDM generally started with a higher pre-pregnancy weight and BMI. Retnakaran and colleagues (13) assessed one year pre-conception to one year post-pregnancy change in physical activity in 238 pregnant women recruited at the time of their GDM screening. Notably, women with GDM significantly increased leisure-time activity, but not work or sport-related activities, compared to women without GDM. In contrast, our study assessed moderate, strenuous and total physical activity, which decreased similarly after pregnancy, in both GDM and non GDM groups. Several key characteristics distinguish these study populations. In particular, the majority of CARDIA participants had their pregnancies in the first 10 years of the study (early 1990’s) and received clinical care from throughout the U.S., while women in the Canadian cohort were recruited more recently from a single site, which may have provided more uniform and updated recommendations about diabetes prevention following GDM, thereby improving behavior change at one year. In addition, participants in CARDIA were assessed at scheduled study examinations, with an average of 1.4 years between pregnancy and the post-pregnancy examination. Thus, we may not have captured short lived post-pregnancy lifestyle changes if they reverted back to pre-pregnancy behaviors prior their next assessment.

Because of their multiple risk factors, including elevated BMI and sedentary behavior, effective interventions aimed at preventing diabetes in women with recent GDM are extremely important. The Diabetes Prevention Program showed in the placebo arm that a GDM history was associated with a higher incidence of progression to type 2 diabetes compared to high risk parous women without GDM (38.4% vs. 25.7%) (29). Even with their increased risk, women with prior GDM benefited greatly from both the intensive lifestyle and metformin arms, with diabetes risk reductions of 53% and 50% respectively (29). Because we found that all women, regardless of GDM diagnosis, gained weight, reduced activity and increased caloric intake following pregnancy, our results additionally highlighted the need to engage all women during pregnancy and postpartum to make significant lifestyle changes, similar to those in the Diabetes Prevention Program (30). Two recent pilot lifestyle interventions (31, 32) have specifically targeted women with recent GDM, but adapting previously successful interventions such as the Diabetes Prevention Program to the needs of young working mothers is especially challenging.

Several studies have identified barriers to postpartum behavior change among women with GDM, including lack of risk perception for developing diabetes (10), possibly due to minimal health education during pregnancy and beyond (9), anxiety and postpartum stress (33), as well as the perception that exercise does not reduce diabetes risk (12). Successful interventions will need to specifically target the needs and barriers to change in this population to enable sustainable behavior change and weight loss. In addition, depending on the state, between 27 and 64% of all births in the U.S. are covered by Medicaid (34) and many women then return to uninsured status following delivery. Lack of health insurance reduces access to primary care services and opportunity for monitoring and interventions to promote and sustain lifelong behavior change. Successful future interventions may need to promote healthy post-pregnancy behavior change, as well as to reach out to uninsured and lesser insured high risk populations to prevent diabetes.

The strengths of our study include use of the CARDIA study, a more than 20 year prospective cohort study design with high rates of follow-up of a biracial U.S. population and use of standardized pre-conception and post-pregnancy repeated anthropometric, dietary and physical activity measures. The longitudinal nature of data collection enhanced the validity of our pre-conception measures and enhanced the feasibility of multiple adjustments in analyses. Studies that are designed to recruit women with GDM during or after pregnancy and collect pre-conception information at that time may be limited by recall bias. In addition, our study benefitted from the GDM validation study by Gunderson and colleagues (3) which showed high sensitivity and specificity of self-reported GDM. We also examined associations separately for black and white racial groups, and by pre-pregnancy BMI, and found consistent associations.

Our study has several limitations. First, CARDIA is an observational study that was designed to assess the development of cardiovascular disease, and not a pregnancy cohort study. Thus the time interval for obtaining post-pregnancy measurements was variable. The amount of time that passed between the pre-pregnancy examination and pregnancy, as well between pregnancy and the post-pregnancy examination may have affected weight and health behaviors. We accounted for these intervals by excluding post-pregnancy examinations that occurred more than five years after the pre-pregnancy examination for anthropometric and weight outcomes. We also adjusted all analyses for the interval between the delivery and post-pregnancy examination. In addition, we found that neither the interval between the pre-pregnancy examination and delivery nor the interval between delivery and the post-pregnancy examination changed the results. However, we may have missed short-lived post-pregnancy changes that were not sustained longer than one year. Second, although self-report of GDM was validated by chart review (3), it is possible that we missed diagnoses of GDM within the CARDIA cohort but this is unlikely given that GDM was self-reported during a period of universal screening for GDM and that GDM requires both treatment and heightened monitoring for patients. If substantial numbers of women with a history of GDM had been misclassified, we may have failed to detect a difference in changes weight and health behaviors between the two groups. However, about 11 percent of women in the cohort reported more than one GDM complicated pregnancies (totaling about seven percent of all pregnancies during 20 years), which is not less than the expected prevalence of GDM (1). Third, we do not have clinical information on the severity of GDM, medications used for GDM treatment, or gestational weight gain, and were unable to assess the impact of these variables on post-pregnancy weight or health behaviors. Fourth, as with other observational studies, we are limited by the data collection instruments to assess diet and physical activity. These CARDIA instruments have been validated within the larger cohort (21, 22, 24), but they have not been tested among the sub-group of women before and after pregnancy, and may be less sensitive to differences within this group. Finally, we did not assess all aspects of dietary intake in this study. Interestingly, we noted an increase in fiber intake from five to 15 gm in both groups. Likely women increased their post-pregnancy fiber intake relative to their increased total daily caloric intake, but further study into dietary quality could help target specific post-pregnancy dietary recommendations.

In conclusion, our study found that both women with and without GDM had increased post-pregnancy weight, BMI and adverse health behaviors. GDM was not associated with significant post-pregnancy differences in weight, BMI, waist circumference, diet or physical activity compared with parous women without GDM. Increased postpartum weight and decreased physical activity are risk factors for the progression to type 2 diabetes. Our study indicates the need for effective pregnancy and postpartum interventions, especially among women with GDM, to promote sustained and successful behavior change to reduce obesity and diabetes risk.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: Dr. Wendy Bennett is support by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 5K23HL098476– 02; CARDIA data collection was supported by contracts N01-HC-48047, N01-HC-48048, N01-HC-48049, N01-HC-48050, and N01-HC-95095 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Yeh is supported by NIDDK Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60 DK079637).

Wendy Bennett is the study guarantor and takes full responsibility for the work as a whole.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: W.L.B. contributed to study design, data interpretation and wrote manuscript. S-H.L. analyzed the data, edited the manuscript and contributed to data interpretation. H-C.Y. contributed to study design, data interpretation and editing of the manuscript. W.K.N. contributed to study design and editing of the manuscript. E.P.G. contributed to study design and editing the manuscript. C.E.L. contributed to study design and reviewing the manuscript. J.M.C contributed to study design, data interpretation and editing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Wendy L. Bennett, Email: wbennet5@jhmi.edu, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 2024 E. Monument Street, Room 2-611, Baltimore, MD 21205, Phone: 410-502-6081, Fax: 410-955-0476.

Su-Hsun Liu, Email: shliu@jhsph.edu, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore MD 21205, Phone: 443-520-5399.

Hsin-Chieh Yeh, Email: hyeh1@jhmi.edu, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, 2024 E. Monument St, Suite 2-500, Baltimore, MD 21287, Phone 410-614-4316, Fax 410-955-0476.

Wanda K. Nicholson, Email: wknichol@med.unc.edu, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, 3027 Old Clinic Building; CB#7570, University of NC-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7570, Phone: 919-843-7851, Fax: 919-966-6001.

Erica P. Gunderson, Email: Erica.Gunderson@kp.org, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2000 Broadway, Oakland, CA 94612, Phone: 510-627-2647, Fax: 510-627-7325.

Cora E. Lewis, Email: clewis@mail.dopm.uab.edu, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama School of Medicine, Medical Towers 734, 1717 11th Avenue South, Birmingham, Alabama 35205, Phone: 205-934-6383, Fax: 205-934-7959.

Jeanne M. Clark, Email: jclark1@jhmi.edu, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, 2024 E. Monument Street, Room 2-600, Baltimore, MD 21205.

References

- 1.Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care. 2007;30 (Suppl 2):S141–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunderson EP, Lewis CE, Tsai AL, et al. A 20-year prospective study of childbearing and incidence of diabetes in young women, controlling for glycemia before conception: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Diabetes. 2007;56:2990–2996. doi: 10.2337/db07-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feig DS, Zinman B, Wang X, et al. Risk of development of diabetes mellitus after diagnosis of gestational diabetes. CMAJ. 2008;179:229–234. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons D. Diabetes during and after pregnancy: screen more, monitor better. CMAJ. 2008;179:215–216. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and Recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:251–260. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratner RE, Christophi CA, Metzger BE, et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4774–4779. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabbe S, Hill L, Schmidt L, et al. Management of diabetes by obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:643–647. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim C, McEwen LN, Kerr EA, et al. Preventive counseling among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007 doi: 10.2337/dc07-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim C, McEwen LN, Piette JD, et al. Risk Perception for Diabetes among Women with Histories of Gestational Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007 doi: 10.2337/dc07-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kieffer EC, Sinco B, Kim C. Health behaviors among women of reproductive age with and without a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1788–1793. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Symons Downs D, Ulbrecht JS. Understanding exercise beliefs and behaviors in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:236–240. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Sermer M, et al. Gestational diabetes and postpartum physical activity: evidence of lifestyle change 1 year after delivery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1323–1329. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1179–1190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes GH, Cutter G, Donahue R, et al. Recruitment in the Coronary Artery Disease Risk Development in Young Adults (Cardia) Study. Control Clin Trials. 1987;8:68S–73S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(87)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cutter GR, Burke GL, Dyer AR, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in young adults. The CARDIA baseline monograph. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12:1S–77S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis CE, Smith DE, Wallace DD, et al. Seven-year trends in body weight and associations with lifestyle and behavioral characteristics in black and white young adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:635–642. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderssen N, Jacobs DR, Jr, Sidney S, et al. Change and secular trends in physical activity patterns in young adults: a seven-year longitudinal follow-up in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:351–362. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs DR, Jr, Hahn LP, Haskell WL, et al. Validity and reliability of a short physical activity history: CARDIA and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. J Cardiopulmon Rehabil. 1989;9:448–459. doi: 10.1097/00008483-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sidney S, Jacobs DR, Jr, Haskell WL, et al. Comparison of two methods of assessing physical activity in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:1231–1245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs DR, Jr, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, et al. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:81–91. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald A, Van Horn L, Slattery M, et al. The CARDIA dietary history: development, implementation, and evaluation. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991;91:1104–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu K, Slattery M, Jacobs D, Jr, et al. A study of the reliability and comparative validity of the cardia dietary history. Ethn Dis. 1994;4:15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baptiste-Roberts K, Barone BB, Gary TL, et al. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes among women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2009;122:207–214.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratner RE, Christophi CA, Metzger BE, et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4774–4779. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Albright CL, et al. A pregnancy and postpartum lifestyle intervention in women with gestational diabetes mellitus reduces diabetes risk factors: a feasibility randomized control trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1519–1525. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim C, Draska M, Hess ML, et al. A web-based pedometer programme in women with a recent history of gestational diabetes. Diabet Med. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett WL, Ennen CS, Carrese JA, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of postpartum follow-up care in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: a qualitative study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:239–245. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) [Accessed July 16, 2012];Maternal and Child Health Update: States Makes Progress Towards Improving Systems of Care. 2010 2011 http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF. [Google Scholar]