Abstract

Cardiac hypertrophy has been well-characterized at the level of transcription. During cardiac hypertrophy, genes normally expressed primarily during fetal heart development are reexpressed, and this fetal gene program is believed to be a critical component of the hypertrophic process. Recently, alternative splicing of mRNA transcripts has been shown to be temporally regulated during heart development, leading us to consider whether fetal patterns of splicing also reappear during hypertrophy. We hypothesized that patterns of alternative splicing occurring during heart development are recapitulated during cardiac hypertrophy. Here we present a study of isoform expression during pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy induced by 10 days of transverse aortic constriction (TAC) in rats and in developing fetal rat hearts compared to sham-operated adult rat hearts, using high-throughput sequencing of poly(A) tail mRNA. We find a striking degree of overlap between the isoforms expressed differentially in fetal and pressure-overloaded hearts compared to control: forty-four percent of the isoforms with significantly altered expression in TAC hearts are also expressed at significantly different levels in fetal hearts compared to control (P < 0.001). The isoforms that are shared between hypertrophy and fetal heart development are significantly enriched for genes involved in cytoskeletal organization, RNA processing, developmental processes, and metabolic enzymes. Our data strongly support the concept that mRNA splicing patterns normally associated with heart development recur as part of the hypertrophic response to pressure overload. These findings suggest that cardiac hypertrophy shares post-transcriptional as well as transcriptional regulatory mechanisms with fetal heart development.

Keywords: heart development, cardiac hypertrophy, alternative splicing, RNAseq

1. Introduction

Over twenty years ago, hearts undergoing hypertrophy were found to revert to a gene expression pattern normally associated with fetal heart development [1,2]. Collectively this is known as the fetal gene program. Many of the genes considered part of the fetal gene program encode critical components of the sarcomere or enzymes involved in metabolism. Hallmarks of the fetal gene program include upregulation of atrial natriuretic peptide [3], β-myosin heavy chain [4–6], and skeletal α-actin [7], as well as downregulation of metabolic genes such as glucose transporter GLUT4 (relative to GLUT1 expression [8]), and enzymes critical for fatty acid oxidation [2,9]. The re-expression of the fetal gene program is thought to be a protective mechanism for the heart. During hypertrophy, the heart shifts from an oxygen-rich environment with fatty acids available for energy to an oxygen-poor environment with glucose as the main energy source, and expresses fetal genes that are better suited to function in this different metabolic environment [2]. The extent and regulation of this phenomenon has been studied and reviewed extensively [1,2,10,11]. While re-expression of the fetal gene program has been observed and documented for years, more recently other post-transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms have also been shown to be critical for cardiac hypertrophy [12–16]. With this new knowledge, it seems plausible that the changes observed in cardiomyocytes during hypertrophy arise from orchestrated phenotypic switching on multiple levels of regulation.

The process of removing introns from a premature mRNA transcript occurs in most eukaryotes, but not every transcript is processed the same way. The selective inclusion or exclusion of specific exons or parts of exons is referred to as alternative splicing. Alternative splicing has the ability to change gene expression, coding sequence, translational efficiency, and mRNA localization [17]. Sequencing the human genome revealed that there are a surprisingly small number of protein-encoding genes given the diversity of proteins and enzymes required for the many specialized functions observed in different tissues. It is now clear that some of this diversity is produced by the process of alternative splicing [18,19]. In fact, more than 95% of human genes are alternatively spliced [20]. Splicing has been documented to change in a wide variety of developmental, physiological, and disease processes [21,22]. More recently alternative splicing has been shown to play a critical role in heart development [23–27] and to be altered in cardiac pathologies including hypertrophy [12,28,29] and heart failure [30–32].

Throughout organogenesis and after birth, the heart must adapt to an increased workload caused by changing pressures and resistances within the adult vascular system. In 2008, Kalsotra et al. showed that cardiac development involves a specific and coordinated program of alternative splicing events, greater than 60% of which were conserved between mouse and chicken embryonic hearts. To put this number in context, less than 20% of all alternative exon (cassette-type) splicing events are conserved between human and mouse. This high degree of conservation strongly suggests a functional role for alternative splicing [33]. In addition, deletion of specific splicing factors that control alternative splicing in heart development has shown that proper regulation of splicing is needed for normal heart development [23–27].

Alternative splicing has been shown to change critical properties of cardiomyocytes including compliance [34,35], protein-protein interactions [12], calcium handling, and contractility [23]. A more thorough understanding of how alternative splicing contributes to cardiac hypertrophy could not only increase our understanding of how RNA processing changes in response to physiological cues, but could also potentially contribute to identifying novel drug targets to modulate cardiac remodeling. Accordingly, the main goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that specific fetal splicing patterns are re-expressed in surgically-induced pressure-overload hypertrophy in rats using high-throughput sequencing (HTS or RNAseq) to quantify poly(A) tail mRNA species. We compared mRNA isolated from ventricles of hearts undergoing pressure-overload hypertrophy, sham-operated hearts, and fetal hearts and identified the splicing events that occur in both fetal and hypertrophied hearts, but not sham-operated adult hearts.

2. Materials and methods

Detailed methods for all procedures and analyses are provided in the Online Supplementary materials.

2.1. Animals

All studies were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [36] and approved by the University of Virginia’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 23 Sprague-Dawley rats were used for these studies.

2.2. Tissue harvest from fetal and adult rats

Five rats were timed, pregnant females; fetuses were harvested by caesarean section on gestational day 18 and the dams were sacrificed immediately afterwards. Fetal hearts from each litter were pooled; three of these litters were used for RNAseq experiments. Four unoperated adult male rats (365 ± 15 g) served as adult controls in splicing validation assays.

2.3. Minimally-invasive approach to transverse aortic constriction

Seven males (308 ± 35 g) underwent the transverse aortic constriction (TAC) procedure and seven males (306 ± 28 g) were used as sham-operated controls. Three rats from the TAC and sham groups were used for high-throughput sequencing. Three separate rats from both TAC and sham groups were used for histology. We adapted a minimally-invasive approach to transverse aortic constriction originally described by Pu et. al in mice [37]. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats were subjected to TAC using a 4-0 silk suture tied around a 19-gauge needle [38]. Ten days after surgery, rats were euthanized using pentobarbital and left ventricular tissue was harvested; this time point was chosen because previous work has shown that this time point after aortic banding has the largest number of gene expression changes [39]. In addition to heart weight-to-body weight ratio, the extent of hypertrophy was confirmed on the cellular level by measuring myocyte cross-sectional area in approximately 1000 myocytes per animal.

2.4. RNAseq data generation and analysis

Five micrograms of high-quality poly(A) tail mRNA was used as starting material for the Illumina mRNA seq library preparation kit and was prepared to manufacturer’s directions (Illumina). Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIax as 42 or 63 base pair paired-end reads. Tophat v1.3.1 [40] was used to align all reads including junction-spanning reads back to the rat genome (Ensembl RGSC3.4). Cufflinks v1.0.3 [41] was used to identify differential splicing, promoter usage, and gene expression changes between experimental groups. Using similar criteria to Lee et al. [28], we defined statistical significance in expression as > 1.5 absolute fold-change, q-value (an adjusted p-value for multiple testing) < 0.05, and Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million reads mapped (FPKM) > 3; FPKM is a measure of expression used in high-throughput sequencing data that is normalized for both transcript length and total number of reads sequenced. All bioinformatics analyses and comparisons were implemented and performed using in-house scripts written in Unix, R, Python, or Perl.

2.5. PCR validation

We validated our RNAseq results against a previous study of alternative splicing in heart development [33]. Splice variants in fetal compared to adult hearts identified both by Kalsotra et al. [33] and by our analysis were validated by one step PCR starting with 500 ng RNA and amplified for 25 cycles (Invitrogen). Custom primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) were designed to flank the alternatively spliced region. PCR products were electrophoresed and visualized with ethidium bromide-stained 2–5% Agarose-1000 gels (Invitrogen). Gel band intensities were measured using BioRad ImageLab software. The percentage inclusion of the alternative region was calculated as [inclusion band intensity / (inclusion band intensity + exclusion band intensity)] × 100. Percentage inclusion values were arcsine-transformed for statistical testing [42]. For validation of previously reported splicing differences between fetal and adult samples, two-tailed unpaired t-tests were used. Comparison of inclusion levels across TAC, fetal, and sham groups employed analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls post-tests where appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Successful induction of hypertrophy in adult rats

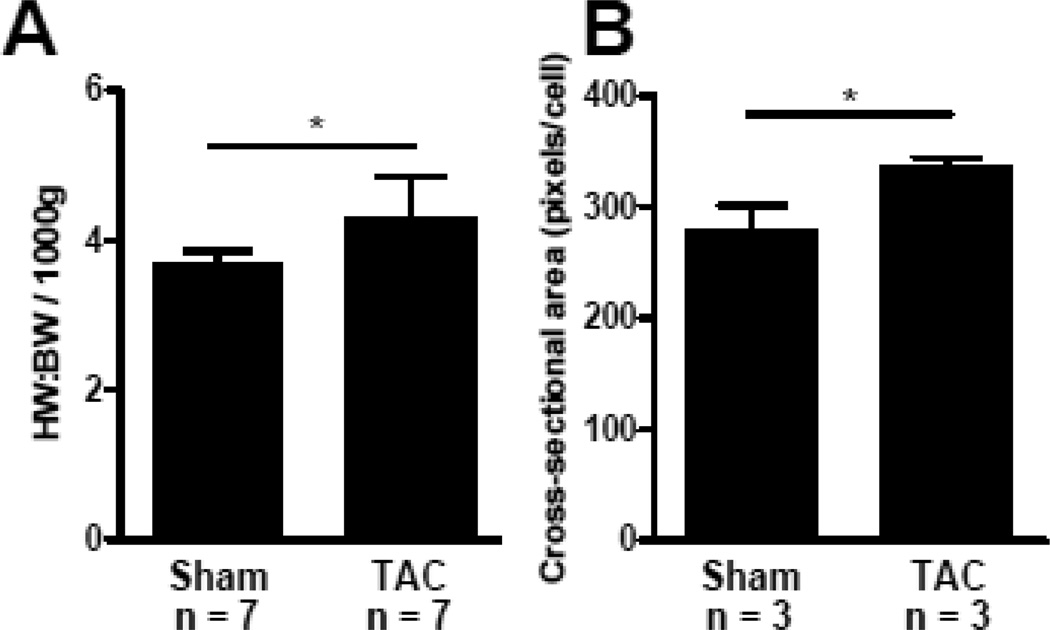

The minimally-invasive approach to transverse aortic constriction [37] employed here induced significant hypertrophy in rats by post-operative day 10, as demonstrated by a significantly higher heart weight to body weight (HW:BW) ratio (Fig. 1A) and significantly larger cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (Fig. 1B) in TAC animals compared to sham-operated controls. The average TAC HW:BW per 1000g of tissue was greater (4.29 ± 0.56) than the average for the sham group (3.70 ± 0.16). The average cross-sectional area of the TAC group was larger (336.7 ± 3.8 pixels) than the sham group (293.2 ± 3.5 pixels).

Figure 1. Induction of hypertrophy with minimally-invasive approach to TAC.

A, TAC rats had increased heart weight to body weight ratio per 1000 g of tissue compared to sham-operated rats 10 days after surgery. B, TAC cardiomyocytes had larger cross-sectional area compared to sham-operated cardiomyocytes (approximately 1000 cell measurements per animal). * indicates P < 0.05.

3.2. Similarities in gene expression between hypertrophy and heart development

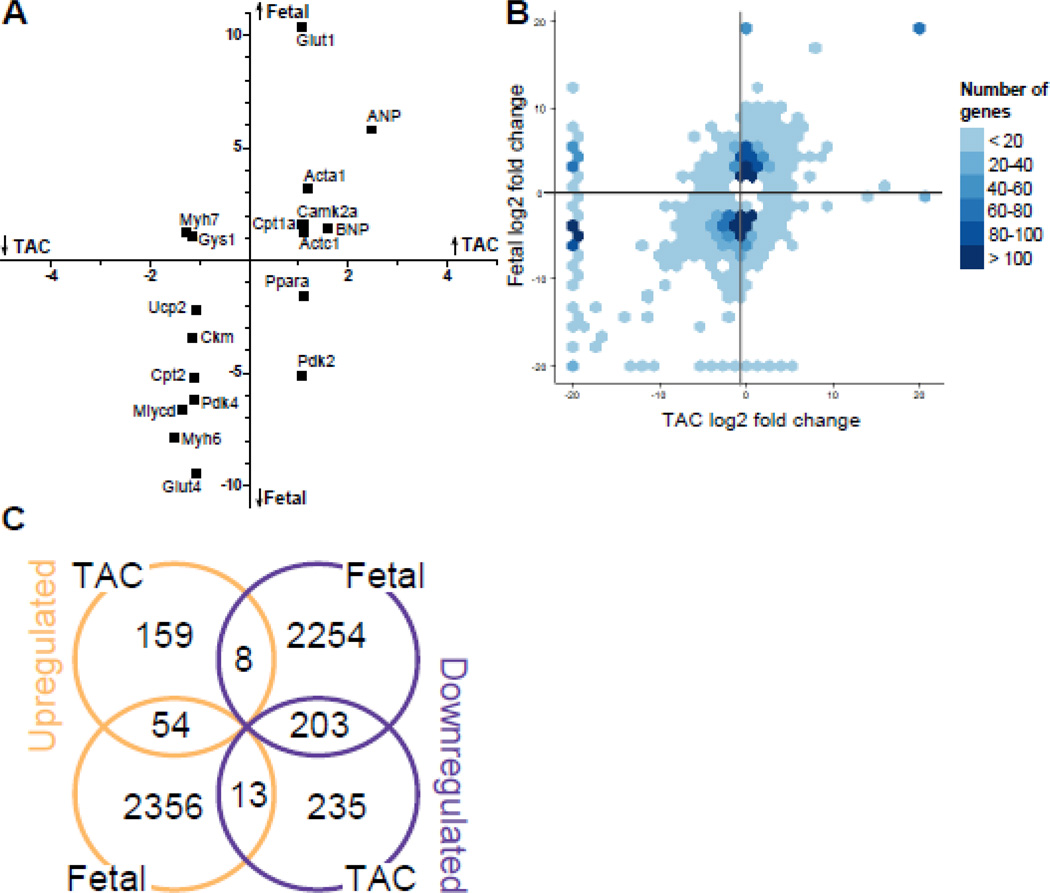

In total, our data set included 267,727,027 reads sequenced across our three experimental groups (Table 1). The concept that a fetal gene program is re-expressed during cardiac hypertrophy suggests that our analysis should identify a number of genes whose expression is increased or decreased in both TAC and fetal hearts relative to sham-operated adults. We evaluated 18 genes that are commonly mentioned as members of the fetal gene program and found that 14 of the 18 known members of the fetal gene program [2,3] changed in the same direction in both TAC and fetal compared to sham, with the fetal changes typically of greater magnitude (Fig. 2A). Plotting fold changes in fetal hearts against those induced by TAC for all significantly regulated genes revealed as expected that a large number of genes differentially regulated in fetal hearts are not altered by TAC (Fig. 2B, dark blue clusters along y-axis). A relatively small number of genes are significantly regulated in TAC alone (Fig. 2B, points along x-axis), while a substantial number of genes change in the same direction in both groups (Fig. 2B, points in upper right and lower left quadrants). Of 221 genes significantly upregulated in TAC compared to sham, almost 25% (54 genes) were also upregulated in fetal hearts compared to sham (Fig. 2C). 26,640 genomic locations were expressed above 3 FPKM in at least one of our experimental groups. These genomic locations include unannotated genes, noncoding RNAs, and microRNA genes. If each of these genes were independently regulated, then the upregulation of 9.1% (2,423/26,640) of those genes in fetal hearts and 0.83% (221/26,640) of those genes in TAC hearts we observed would suggest that roughly 20 genes should be upregulated in both groups (0.091*0.0083*26,640). In fact, we observed more than twice as much overlap. As detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1, the probability of observing 54 or more commonly upregulated genes in the absence of shared regulatory mechanisms would be P = 1.16 × 10−11while the probability of the degree of shared downregulation observed in these two groups would be 3.5 × 10−90.

Table 1.

Summary of sequencing results for each experimental group

| Sample | Sequenced fragments | Aligned fragments | Percent Aligned (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAC1 | 28.9 M | 18.3 M | 63.28 |

| TAC2 | 24.2 M | 17.4 M | 71.51 |

| TAC3 | 44.9 M | 32.1 M | 71.59 |

| Sham1 | 54.0 M | 33.8 M | 62.65 |

| Sham2 | 46.1 M | 32.7 M | 71.04 |

| Sham3 | 85.3 M | 55.6 M | 65.19 |

| Fetal1 | 73.4 M | 54.3 M | 73.98 |

| Fetal2 | 76.8 M | 52.4 M | 68.16 |

| Fetal3 | 102 M | 74.2 M | 72.92 |

Figure 2. Comparison of gene expression changes during hypertrophy and heart Development.

A, Scatterplot of known members of the fetal gene program. The x- and y-coordinates represent log2 fold changes of TAC and fetal groups relative to sham, respectively. B, Hexagonal histogram showing differential expression of significantly altered genes (absolute fold change > 1.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05) relative to sham. C, Euler diagram showing overlap of differential gene expression between TAC and fetal samples compared to sham. Of the 221 significantly regulated genes in TAC, 54 were regulated in the same direction in the fetal samples, 8 in the opposite direction of fetal hearts, and 159 were upregulated only in TAC.

3.3. Changes in gene and isoform expression are independent in both fetal and hypertrophic hearts

Our RNAseq analysis can detect significant changes in expression of an isoform due to alternative splicing, or due to changes in overall gene expression levels for that gene. We therefore examined what fraction of detected changes in isoform expression was at least partly explained by changes in gene expression (Fig. 3). In comparisons of fetal and sham hearts, we detected 10,553 significant changes in isoform expression, 53.5% of which were associated with significant, concordant changes in gene expression (i.e., isoform and gene expression levels both increased or decreased); 46.5% of changes in isoform expression occurred in the absence of detected changes in gene expression (Fig. 3A). Comparisons of TAC vs. sham hearts were notable for the much smaller number of both isoform and gene expression changes, and for a much higher percentage (77.5%) of isolated changes in isoform expression (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Changes in gene and isoform expression are distinct in both fetal and hypertrophic hearts.

A, Each isoform expressed in the fetal or sham group above 3 FPKM is plotted as a gray dot, where the x-coordinate is the gene expression fold change relative to sham and the y-coordinate is the isoform fold change (relative to sham). Blue dots represent a transcript where both the isoform and gene expression are significantly different from sham (absolute fold change >1.5 and an adjusted p-value < 0.05). Red dots represent transcripts where only isoform expression is significantly altered. B, TAC gene and isoform expression plotted in a similar fashion as A.

3.4. Comparison of splicing events in hypertrophy and heart development identifies significant overlap

The Euler diagram of significantly altered isoform expression in Fig. 4A reveals a striking overlap between TAC and fetal groups; 44% of isoforms significantly altered in TAC showed concordant changes in fetal hearts. When we exclude all single isoform genes, we measured 23,190 isoforms that were expressed above 3 FPKM in at least one of our experimental groups. If each of these isoforms were independently regulated, then downregulation of 22.3% (5,164/23,190) of those isoforms in fetal hearts and 8.1% (1,885/23,190) of those isoforms in TAC hearts would suggest that approximately 421 isoforms should be downregulated in both groups (0.08*0.22*23,190). The amount of overlap that we observed was more than double this number. The probability of observing 934 or more commonly downregulated isoforms in the absence of shared regulatory mechanisms would be P = 3.42 × 10−164while the probability of the degree of shared upregulation observed in these two groups would be 8.08 × 10−25 (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for calculations). The hexagonal histogram of isoform fold changes in Fig. 4B shows the distribution of significant splicing events and similarities between the TAC and fetal groups. Here we see that many of the isoforms differentially expressed in either group relative to sham are located in the lower left or upper right quadrants, demonstrating concordant changes in expression. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed that these groups of shared up- and down-regulated isoforms are enriched for GO terms associated with sarcomeric and cytoskeletal organization, RNA processing and metabolism, and muscle contraction (Table 2). All significant isoforms of genes within the ‘cytoskeleton organization’ cluster identified by DAVID (FPKM > 3, q-value < 0.05, and log2 fold change > 1.5) are plotted as heat map in Fig. 5A to show similarities in expression. Indeed, 72% of isoforms significantly altered in TAC are concordantly altered in fetal hearts. The shared isoforms with the most significant changes included: Ablim1, Ctnnb1, and Cryab (listed in Fig. 5A); Ptbp1, Hnrnpk, and Rbm39 (RNA processing); and Fxyd1 and Myh6 (muscle contraction). Many of these terms have previously been identified as associated with hypertrophic growth or as targets of alternative splicing [29,33,43].

Figure 4. Significant overlap of splicing patterns in heart development and hypertrophy.

A, Overlap of changes in isoform expression between TAC and fetal samples compared to sham as shown in Euler diagram. Four hundred fifty-three transcripts are concordantly upregulated in both TAC and fetal hearts, while 934 isoforms are downregulated in both groups. B, The hexagonal histogram showing expression of each significant isoform (absolute fold change > 1.5 and an adjusted p-value < 0.05) relative to sham. C, Exon diagram of tropomyosin 3 (Tpm3) demonstrates multiple splicing patterns; a mutually exclusive exon (5a - red or 5b - blue) and three alternative terminal exons (TermA - green, TermB - purple, or TermC - yellow). D, The bar chart shows percentage of all Tpm3 transcripts that contain each splicing event based on band intensity from gel electrophoresis (n = 4). The expression of mutually exclusive exon 5a is statistically greater in both TAC and sham groups compared to the fetal group. In contrast, the expression of terminal exon Term A is significantly higher in sham than compared to both TAC and fetal groups, where * represents P <0.05.

Table 2.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of biological processes associated with up- and down-regulated isoforms seen in both hypertrophy and development

| Gene ontology term | No. of genes |

Fold enrichment |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeleton organization (GO:0007010) | 35 | 2.13 | 4.4E-05 |

| Messenger RNA processing (GO:0006397) | 28 | 2.58 | 1.1E-05 |

| Muscle contraction (GO:0006936) | 12 | 2.70 | 4.6E-03 |

| Intracellular transport (GO:0046907) | 49 | 1.93 | 1.5E-05 |

| Response to reactive oxygen species (GO:0000302) | 13 | 2.73 | 2.6E-03 |

| Microtubule-based transport (GO:0010970) | 5 | 4.61 | 2.1E-02 |

| Endocytosis (GO:0006897) | 16 | 2.01 | 1.3E-02 |

| Cellular protein complex assembly (GO:0043623) | 13 | 2.19 | 1.5E-02 |

| Regulation of cell size (GO:0008361) | 18 | 1.88 | 1.5E-02 |

| Response to estradiol stimulus (GO:0032355) | 12 | 2.80 | 3.5E-03 |

| Glucose metabolic process (GO:0006006) | 19 | 2.09 | 4.3E-03 |

| Regulation of actin filament polymerization (GO:0030833) | 9 | 4.46 | 7.1E-04 |

| Muscle organ development (GO:0007517) | 20 | 2.29 | 1.1E-03 |

Representative GO terms from significant GO term clusters from the 453 upregulated isoforms and the 934 isoforms downregulated in both TAC and fetal hearts. No. of genes = number of genes associated with that GO term in the dataset. Fold enrichment quantifies the extent that each GO term is overrepresented in the dataset compared to the rat genome. A P-value signifies the degree of statistical significance of the degree of enrichment.

Figure 5. Similarities and differences between isoform expression observed in fetal heart development and TAC.

A, Top gene ontology term “cytoskeleton organization” (GO: 0007010) for isoforms that were commonly regulated in both TAC and fetal hearts. B, TAC-specific most significant gene ontology term “regulation of small GTPase-mediated signal transduction” (GO: 0051056). C, Fetal-specific most significant gene ontology term “cell cycle” (GO: 0007049). All significant isoforms of genes within a gene ontology cluster identified by DAVID (FPKM > 3, q-value < 0.05, and log2 fold change > 1.5) are plotted as a heat map to show similarities and differences between TAC and fetal isoform expression.Gene symbols of selected significant isoforms are listed above the heat map with lines drawn to the corresponding bar in the heat map. White dots within heat map bars denote statistical significance in isoform expression relative to sham.

3.5. Differences between splicing patterns observed in fetal heart development and TAC

Despite the striking degree of overlap between splicing patterns observed in TAC and fetal hearts relative to sham, half the changes observed in TAC hearts were unique. To gain insight into the potential functional impact of shared and unique splicing patterns, we separated our significant isoform changes into those that occurred in both TAC and fetal hearts, those that only occurred in TAC, and those that only occurred in development. We then used gene ontology analysis to look for differences between the groups. We found that the isoforms specific to development or TAC had unique features not seen in the overlap group. Most notably, isoform expression changes that occurred only in TAC hearts were enriched for components of signal transduction pathways, including regulation of small GTPase-mediated signal transduction and positive regulation of MAP kinase kinase kinase (Supplementary Table 3); some of the most significantly altered isoforms unique to TAC included Arfgap2, Cyth2, and Rapgef2 (others listed in Fig. 5B). Most of the isoforms in this cluster are significant in the TAC group only. By contrast, fetal-specific isoform changes were enriched in cell cycle and DNA maintenance (i.e. response to DNA damage, chromosome segregation, and chromatin organization; Supplementary Table 3). Some of the most significantly altered isoforms unique to fetal hearts included Dlg1, Fbxo5, and Gmnn (others listed in Fig. 5C). The isoform expression changes of the top group-specific gene ontology clusters are depicted as heat maps in Fig. 5.

3.6.1. PCR validation of significant isoform identifies both developmentally- and hypertrophy-related alternative splicing

One advantage of RNAseq is the ability to identify multiple complex splicing patterns within a single gene. As an individual example of multiple splicing patterns, the tropomyosin 3 gene (Tpm3) contains mutually exclusive exons 5a or 5b and three alternative terminal exons (Fig. 4C). Previous literature has shown that the mutually exclusive exon 5 is developmentally regulated, i.e. fetal and adult tissues express different exons. Our RNAseq analysis detected both developmental regulation of exon 5 (higher levels of exon 5a in both adult groups compared to fetal), in agreement with previous reports [44], and hypertrophy-associated reversion to a fetal pattern of terminal exon splicing (lower levels of terminal exon A in TAC and fetal groups compared to sham). We confirmed both changes by PCR (Fig. 4D). Ninety percent and 96% of Tpm3 in TAC and sham hearts contain exon 5a, respectively, while fetal hearts express exon 5a in 73% of Tpm3 transcripts (Fig. 4D). The predominant terminal exon used in the sham group is terminal exon A, referred to as TermA in Fig. 4D which makes up 51.85 ± 8.66% of all terminal exons expressed in the sham group. This terminal exon A is not the predominant terminal exon in TAC and fetal groups and is expressed at a significantly lower level (22.81 ± 7.45% in fetal hearts and 23.36 ± 10.73% in TAC hearts).

3.6.2. PCR validation of RNAseq results identifies known splice variants that are regulated in heart development

To further validate our RNAseq findings, we compared differences in alternative splicing between fetal and adult hearts detected by our analysis to published reports on alternative splicing in heart development, and confirmed individual alternative splicing events by PCR. Kalsotra et al. identified developmental isoform switches that occur during murine heart development by measuring percentage alternative exon inclusion on embryonic days 14 and 18 (E14 and E18, respectively), postnatal day 1, and adulthood. Of the 48 isoform switches that had percent inclusion changes >20%, 33 splicing events changed more dramatically from E18 to adulthood than from E14 to E18. The fetal hearts in our study were harvested at embryonic day 18 as well, which allowed us to directly compare significant differences between fetal and adult rat hearts identified by our analysis to those identified by Kalsotra using exon-specific microarrays. Of the 33 events identified by Kalsotra with large changes between E18 and adulthood, 17 events in our dataset had similar developmental trends in exon inclusion percentage as estimated from FPKM values. Twelve of these events were detected and reported as statistically significant in our bioinformatics analysis. PCR validation confirmed statistically significant changes in percent inclusion for all 12 of these splicing events (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Identification and validation of known developmental splicing events.

A comparison of our fetal and sham groups identified 12 of 33 splicing events reported by Kalsotra et al. as significantly regulated in the same pattern in our data. PCR validation confirmed all 12 events are significantly different between E18 and adult hearts (n = 4 for each group and P < 0.05 for all events).

3.7. Potential upstream regulators of isoform changes seen in heart development, hypertrophy, or both processes

We used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Inc.; Redwood City, CA) to identify potential upstream regulators of the significant isoform expression changes (Supplementary Table 4). This analysis incorporates information on signaling transduction pathways, protein-protein interactions, and transcriptional regulation to determine molecules that are upstream of a given list of gene names. We used this feature to identify candidate signaling pathways that might be controlling the changes in isoform expression that we observed in TAC and fetal hearts. There was a large amount of overlap between the upstream regulators of hypertrophy and fetal heart development including insulin receptor (INSR), insulin growth factor receptor (IGFR1), mediator of RNA polymerase II transcription subunit 30 (MED30), transcription factor GATA4, titin (TTN), and growth hormone (GH1). There were several upstream regulators that were specific to TAC including both of the p38 MAPK subunits (MAPK11 and MAPK14), aldosterone receptor (NR3C2), and MURF3, a protein that links sarcomeres to microtubules (also known as tripartite motif-containing 54, TRIM54) [45]. There were more upstream regulators that were unique to the isoform expression changes seen in fetal hearts including E2F transcription factor 6 (E2F6), MAP kinase kinases 3 and 6 (MAP2K3, MAP2K3), histone deacetylase 5 (HDAC5), retinoblastoma protein (RB1), myocardin (MYOCD), thrombospondin receptor (CD36), and myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2D (MEF2D).

4. Discussion

The changes in individual mRNA isoforms we identified during TAC displayed a striking degree of overlap with changes observed in fetal hearts relative to sham; nearly half of all significant splicing changes we observed in TAC were present and concordant in fetal hearts. These shared isoforms are enriched in gene ontology groups known to be targets of alternative splicing, including sarcomeric and metabolic proteins [29,33,43]. Interestingly, whereas many splicing events identified in fetal hearts were associated with altered overall expression levels of the associated gene, a much greater fraction of the splicing events we identified in TAC samples occurred in the absence of gene expression changes. These observations suggest that alternative splicing plays a relatively greater role in determining mRNA changes during hypertrophy, and relies at least in part on regulatory mechanisms also active during development. Other groups have examined the changes in alternative splicing in murine models of hypertrophy and how these events change with the development of heart failure [28]. Indeed it is important to note that alternative splicing does change in heart failure patients [31] and in response to drugs used to treat heart failure [46]. In addition, recent in vitro experiments have shown that alternative splicing in skeletal muscle cell culture is sensitive to changes in mechanical cues [47].

A wide array of studies has now measured gene expression during heart development, cardiac hypertrophy, and heart failure using microarray analysis. Recently, Dewey et al. combined data from 478 microarray studies and used coexpression network analysis to determine how similar gene expression was during heart development compared to hypertrophied or failing hearts. Given the small number of coexpression modules, the authors questioned the extent and importance of the fetal gene program [48]. Although the focus of our study was alternative splicing, changes in gene expression levels computed from our analysis are consistent with the concept that some developmental patterns of gene expression do recur during hypertrophy. Not surprisingly, many more genes were significantly up- or down-regulated in fetal hearts than in TAC hearts relative to sham-operated adult controls; therefore, the fraction of fetal gene expression changes shared by TAC hearts was small. However, the fraction of the genes significantly altered in TAC that were coordinately regulated in fetal hearts was much higher than would be expected in the absence of shared regulatory mechanisms, suggesting that hypertrophying hearts do re-use some of the same regulatory mechanisms active during heart development.

While this study revealed substantial overlap between splicing patterns in TAC and fetal hearts, both TAC and fetal hearts also displayed many unique splicing differences compared to sham-operated adult hearts. In order to gain preliminary insight into upstream regulatory mechanisms that might explain the similarities and differences we observed between TAC and fetal hearts, we utilized Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. The RNA-binding proteins that control alternative splicing are regulated by canonical signaling cascades and common post-translational modifications [49,50] that would be identified by IPA. The upstream regulatory pathway most strongly associated with changes in isoform expression unique to TAC was p38 MAPK, while shared isoform changes were most strongly associated with insulin signaling. In addition, the upstream regulators of fetal-specific isoforms are known to be critical for heart development, such as myocardin and MEF2D. However, more work is certainly needed to identify RNA binding proteins that bind to significantly altered isoforms in our dataset and understand their role in regulating the changes we observed. In order to begin to identify the functional impact of the splicing patterns reported here, we used gene ontology (GO) analysis to identify functional groups overrepresented among isoforms altered in TAC alone, fetal alone, or both fetal and TAC groups. Not surprisingly, changes in fetal hearts, which are still undergoing cell division [51], included significant upregulation of many more isoforms related to cell cycle. In contrast, isoforms involved in some signaling pathways that have been shown to be essential for cardiac hypertrophy [52,53] were more likely to be altered in TAC hearts.

As an individual example of multiple splicing patterns within a single gene, our analysis showed that of two splicing changes associated with development in the tropomyosin 3 gene (Tpm3), one was re-expressed following 10 days of TAC, while the other was not. The tropomyosin protein family demonstrates tremendous isoform diversity which is driven by four separate genes, multiple promoters, and alternative splicing [44]. While the expression of Tpm3 isoforms in neural tissues and skeletal muscle has been intensely studied, there is considerably less known about the different Tpm3 isoforms in the heart [54]. In our analysis, the mutually exclusive exon 5 expression differed by age, with fetal hearts expressing different levels of exon 5a relative to either adult groups (TAC or sham). In contrast, the terminal exon splicing of both the TAC and fetal groups were more similar to one another than to sham group, suggesting recurrence of fetal splicing patterns in the terminal exon during hypertrophy.

The specific functional consequences of alternative splicing on the function of individual proteins are known for only a relatively small subset of the altered isoforms we identified. One example is Myo1b, a gene that displayed the same alternative splicing event in both fetal and TAC groups in our study. Myo1b is known to function between the cell membrane and actin cytoskeleton as a mechanotransduction sensor [55]. The percentage inclusion of Myo1b exon 11 is higher in both TAC and fetal hearts compared to the sham group; the inclusion of this exon has been shown to increase the sensitivity of Myo1b in sensing tension[56]. An example of a TAC-specific splicing event we detected involves TEA domain family member 1 (Tead1). Tead1 has been shown to be upregulated in hypertrophy [57] and is responsible for the re-expression of components of the fetal gene program [58,59]. We observed a decrease in exon 4 inclusion in TAC hearts compared to the fetal or sham groups. Exclusion of exon 4 does not disrupt the reading frame, but the loss of this exon has been shown to occur during transformation of multiple cell types [60]. Exon 4 is only 12 nucleotides in length and is located in the highly-conserved TEA domain that is responsible for physical interaction with other essential transcription factors for the hypertrophic response, SRF [61] and MEF2 [62]. More work is needed to follow up on the consequences of this TAC-specific isoform and its role in the development of hypertrophy.

Validation is a critical component of any high-throughput study, and we therefore validated the bioinformatics analysis presented here using multiple comparisons to both published data and PCR. First, gene expression levels computed from our analysis confirmed changes known to occur during hypertrophy, including concordant changes in TAC and fetal hearts of 14 of 18 genes frequently identified in the literature as components of the fetal gene program (Fig. 2A). Second, we confirmed that our analysis identified splicing events that were previously reported during fetal heart development. We compared our RNAseq analysis of E18 and adult rat hearts to a prior study using custom microarrays to detect alternative splicing in E18 and adult mouse hearts. Given the different species and methodology, it is not surprising that only about half of the previously reported splicing events were apparent in our sequencing data (17 of 33 events that altered exon percent inclusion by at least 20% were present, with 12 changes reaching statistical significance). More meaningful as a validation of our overall approach to identifying changes in alternative splicing is the fact that all 12 of the events that were reported as statistically significant by our analysis were also significantly different by PCR. As a final validation, in the specific case of tropomyosin 3 even a complex pattern of alternative splicing changes among the fetal, TAC, and sham groups identified by our analysis was confirmed by PCR.

The most common source of error in high-throughput analyses is the potential for false positives. In the present study, we attempted to limit false discovery rates by adjusting for multiple comparisons and using a cutoff of the adjusted p-value, or q-value <0.05. We also required expression levels >3 FPKM and an absolute fold change >1.5x as criteria for recognizing changes in gene or isoform expression. As suggested by our validation against previously reported developmental splicing changes, this conservative approach may result in missing some events (we identified 12 significant events out of the 33 reported by Kalsotra et al.), but provides confidence that reported changes are substantive (all 12 were confirmed on PCR). One potential source of error in our analysis was the higher number of total sequencing reads in the fetal group compared to our TAC and sham groups. In order to test whether this difference in the number of total reads could have affected our conclusions, we randomly downsampled each sample to match the smallest number of reads. Random downsampling did diminish the total number of genes identified as differentially expressed in fetal vs. sham hearts, but the trend of more significant genes and isoforms in the fetal group compared to the TAC group remained (Supplementary Fig. 2), as did the conclusion that a much higher fraction of isoform expression changes in TAC are concordant in fetal hearts than would be expected in the absence of common regulatory mechanisms. Thus the primary results of the present study cannot be attributed to differences in sequencing depth. One other limitation of the present study is that we conducted the analysis at a single time point, 10 days following TAC. We chose this time point because microarray studies had previously identified it as having a large number of gene expression changes [39]. However, there are certainly transient changes in gene expression known to occur prior to 10 days after TAC that would be missed by our analysis; there may also be transient early splicing changes that were similarly missed.

5. Conclusions

We tested the hypothesis that patterns of alternative splicing occurring during heart development recur during cardiac hypertrophy in response to transverse aortic constriction using high-throughput sequencing of mRNA isolated from fetal rats, adult sham-operated rats, and adult rats subjected to 10 days of pressure overload. We found a striking degree of overlap between changes in both gene and isoform expression in TAC and fetal hearts relative to sham. Our data strongly support the concept that mRNA splicing patterns normally associated with heart development recur as part of the hypertrophic response to pressure overload and suggest that cardiac hypertrophy shares post-transcriptional as well as transcriptional regulatory mechanisms with fetal heart development. Our results suggest that a deeper understanding of alternative splicing and its role in cardiac hypertrophy may reveal new mechanistic insight and therapeutic opportunities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We compared mRNA splicing in pressure-overload, sham, and fetal hearts.

RNAseq identified strong overlap between fetal and hypertrophy gene and isoform expression.

We validated our analysis against known developmental changes and PCR.

We report the re-expression of a fetal splicing program in cardiac hypertrophy.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge K. Janes for valuable discussions and technical support from T. Burcin, the University of Virginia Biomolecular Research Facility, and the Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center Surgery Core.

Sources of funding

This work was funded by NIH R01 HL-075639 (JWH), NIH GM-00727 (EGA), and NIH FM- 008136 (EGA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability: Reviewers are able to access raw and processed sequencing files from a reviewers’ only link to Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=bncbxcweymmgiji&acc=GSE42411)

Disclosures

None declared.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Contributor Information

EG Ames, Email: ega2d@virginia.edu.

MJ Lawson, Email: mlawsonvt09@gmail.com.

AJ Mackey, Email: amackey@virginia.edu.

JW Holmes, Email: holmes@virginia.edu.

References

- 1.Frey N, Olson EN. Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:45–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajabi M, Kassiotis C, Razeghi P, Taegtmeyer H. Return to the fetal gene program protects the stressed heart: a strong hypothesis. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12:331–343. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izumo S, Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V. Protooncogene induction and reprogramming of cardiac gene expression produced by pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:339–343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorza L, Pauletto P, Pessina AC, Sartore S, Schiaffino S. Isomyosin distribution in normal and pressure-overloaded rat ventricular myocardium. An immunohistochemical study. Circ Res. 1981;49:1003–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahdavi V, Lompre AM, Chambers AP, Nadal-Ginard B. Cardiac myosin heavy chain isozymic transitions during development and under pathological conditions are regulated at the level of mRNA availability. Eur Heart J. 1984;5(Suppl F):181–191. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/5.suppl_f.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercadier JJ, Lompré AM, Wisnewsky C, Samuel JL, Bercovici J, Swynghedauw B, et al. Myosin isoenzyme changes in several models of rat cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 1981;49:525–532. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz K, De la Bastie D, Bouveret P, Oliviéro P, Alonso S, Buckingham M. Alpha-skeletal muscle actin mRNA’s accumulate in hypertrophied adult rat hearts. Circ Res. 1986;59:551–555. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinberg E, Thienelt C, Lorell B. Pretranslational regulation of glucose-transporter isoform expression in hearts with pressure-overload left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ. 1995;92 I-385(Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sack MN, Disch DL, Rockman HA, Kelly DP. A role for Sp and nuclear receptor transcription factors in a cardiac hypertrophic growth program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6438–6443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry SP, Davidson SM, Townsend PA. Molecular regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Int J Biochem Cell B. 2008;40:2023–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taegtmeyer H, Sen S, Vela D. Return to the fetal gene program: a suggested metabolic link to gene expression in the heart. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1188:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamazaki T, Wälchli S, Fujita T, Ryser S, Hoshijima M, Schlegel W, et al. Splice variants of Enigma homolog, differentially expressed during heart development, promote or prevent hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:374–382. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hang CT, Yang J, Han P, Cheng H-L, Shang C, Ashley E, et al. Chromatin regulation by Brg1 underlies heart muscle development and disease. Nature. 2010;466:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong Y, Tannous P, Lu G, Berenji K, Rothermel BA, Olson EN, et al. Suppression of class I and II histone deacetylases blunts pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circ. 2006;113:2579–2588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.625467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Rooij E, Marshall WS, Olson EN. Toward microRNA-based therapeutics for heart disease: the sense in antisense. Circ Res. 2008;103:919–928. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.183426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado-Olguín P, Huang Y, Li X, Christodoulou D, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, et al. Epigenetic repression of cardiac progenitor gene expression by Ezh2 is required for postnatal cardiac homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:343–347. doi: 10.1038/ng.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keene JD. RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsen TW, Graveley BR. Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature. 2010;463:457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature08909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1413–1415. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang GS, Cooper TA. Splicing in disease: disruption of the splicing code and the decoding machinery. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:749–761. doi: 10.1038/nrg2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalsotra A, Cooper TA. Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:715–729. doi: 10.1038/nrg3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Yang D, Ding JH, Wang W, Chu PH, Dalton ND, et al. ASF/SF2-regulated CaMKIIdelta alternative splicing temporally reprograms excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Cell. 2005;120:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Y, Valley MT, Lazar J, Yang AL, Bronson RT, Firestein S, et al. SRp38 regulates alternative splicing and is required for Ca(2+) handling in the embryonic heart. Dev Cell. 2009;16:528–538. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladd AN, Taffet G, Hartley C, Kearney DL, Cooper TA. Cardiac tissue-specific repression of CELF activity disrupts alternative splicing and causes cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6267–6278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6267-6278.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding J-H, Xu X, Yang D, Chu P-H, Dalton ND, Ye Z, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy caused by tissue-specific ablation of SC35 in the heart. EMBO J. 2004;23:885–896. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanadia RN, Johnstone KA, Mankodi A, Lungu C, Thornton CA, Esson D, et al. A muscleblind knockout model for myotonic dystrophy. Science. 2003;302:1978–1980. doi: 10.1126/science.1088583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J-H, Gao C, Peng G, Greer C, Ren S, Wang Y, et al. Analysis of transcriptome complexity through RNA sequencing in normal and failing murine hearts. Circ Res. 2011;109:1332–1341. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JY, Li W, Zheng D, Zhai P, Zhao Y, Matsuda T, et al. Comparative analysis of mRNA isoform expression in cardiac hypertrophy and development reveals multiple post-transcriptional regulatory modules. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neagoe C, Kulke M, Del Monte F, Gwathmey JK, De Tombe PP, Hajjar RJ, et al. Titin isoform switch in ischemic human heart disease. Circ. 2002;106:1333–1341. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029803.93022.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong SW, Hu YW, Ho JW, Ikeda S, Polster S, John R, et al. Heart failure-associated changes in RNA splicing of sarcomere genes. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:138–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.904698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo W, Schafer S, Greaser ML, Radke MH, Liss M, Govindarajan T, et al. RBM20, a gene for hereditary cardiomyopathy, regulates titin splicing. Nat Med. 2012;18:766–773. doi: 10.1038/nm.2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalsotra A, Xiao X, Ward AJ, Castle JC, Johnson JM, Burge CB, et al. A postnatal switch of CELF and MBNL proteins reprograms alternative splicing in the developing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20333–20338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809045105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opitz CA, Leake MC, Makarenko I, Benes V, Linke WA. Developmentally regulated switching of titin size alters myofibrillar stiffness in the perinatal heart. Circ Res. 2004;94:967–975. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000124301.48193.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahmers S, Wu Y, Call DR, Labeit S, Granzier H. Developmental control of titin isoform expression and passive stiffness in fetal and neonatal myocardium. Circ Res. 2004;94:505–513. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000115522.52554.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Council ISBN Life Sciences. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu P, Zhang D, Swenson L, Chakrabarti G, Abel ED, Litwin SE. Minimally invasive aortic banding in mice: effects of altered cardiomyocyte insulin signaling during pressure overload. Am J Physiol-Heart C. 2003;285:H1261–H1269. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00108.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freeling J, Wattier K, LaCroix C, Li Y-F. Neostigmine and pilocarpine attenuated tumour necrosis factor alpha expression and cardiac hypertrophy in the heart with pressure overload. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:75–82. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.039784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao M, Chow A, Powers J, Fajardo G, Bernstein D. Microarray analysis of gene expression after transverse aortic constriction in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2004;19:93–105. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00040.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trapnell C, Williams B, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, Van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graphpad Software. InStat guide to choosing and interpreting statistical tests. San Diego California USA: GraphPad Software, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bland CS, Wang ET, Vu A, David MP, Castle JC, Johnson JM, et al. Global regulation of alternative splicing during myogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7651–7664. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunning PW, Schevzov G, Kee AJ, Hardeman EC. Tropomyosin isoforms: divining rods for actin cytoskeleton function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregorio CC, Perry CN, McElhinny AS. Functional properties of the titin/connectin-associated proteins, the muscle-specific RING finger proteins (MURFs), in striated muscle. J Muscle Res Cell M. 2005;26:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson ES, Lin C-H, Xiao X, Stoilov P, Burge CB, Black DL. The cardiotonic steroid digitoxin regulates alternative splicing through depletion of the splicing factors SRSF3 and TRA2B. RNA. 2012;18:1041–1049. doi: 10.1261/rna.032912.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schilder RJ, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Cell-autonomous regulation of fast troponin T pre-mRNA alternative splicing in response to mechanical stretch. Am J Physiol-Cell Ph. 2012;303:C298–C307. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00400.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dewey FE, Perez MV, Wheeler MT, Watt C, Spin J, Langfelder P, et al. Gene coexpression network topology of cardiac development, hypertrophy, and failure. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:26–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.941757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heyd F, Lynch KW. Degrade, move, regroup: signaling control of splicing proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blaustein M, Pelisch F, Srebrow A. Signals, pathways and splicing regulation. Int J Biochem Cell B. 2007;39:2031–2048. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahuja P, Sdek P, MacLellan WR. Cardiac myocyte cell cycle control in development, disease, and regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:521–544. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lezoualc’h F, Métrich M, Hmitou I, Duquesnes N, Morel E. Small GTP-binding proteins and their regulators in cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang CL, Coluccio LM. New insights into the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton by tropomyosin. Int Rev Cel Mol Bio. 2010;281:91–128. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)81003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laakso JM, Lewis JH, Shuman H, Ostap EM. Myosin I can act as a molecular force sensor. Science. 2008;321:133–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1159419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laakso JM, Lewis JH, Shuman H, Ostap EM. Control of myosin-I force sensing by alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:698–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911426107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Azakie A, Fineman JR, He Y. Myocardial transcription factors are modulated during pathologic cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. J Thorac Cardiov Sur. 2006;132:1262–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stewart AF, Suzow J, Kubota T, Ueyama T, Chen HH. Transcription factor RTEF-1 mediates alpha1-adrenergic reactivation of the fetal gene program in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1998;83:43–49. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsika RW, Ma L, Kehat I, Schramm C, Simmer G, Morgan B, et al. TEAD-1 overexpression in the mouse heart promotes an age-dependent heart dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13721–13735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuzarte PC, Farrance IK, Simpson PC, Wildeman AG. Tumor cell splice variants of the transcription factor TEF-1 induced by SV40 T-antigen transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1517:82–90. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gupta M, Kogut P, Davis FJ, Belaguli NS, Schwartz RJ, Gupta MP. Physical interaction between the MADS box of serum response factor and the TEA/ATTS DNA-binding domain of transcription enhancer factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10413–10422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maeda T, Gupta MP, Stewart AFR. TEF-1 and MEF2 transcription factors interact to regulate muscle-specific promoters. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2002;294:791–797. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.