Abstract

VZV reactivation produces zoster (shingles) which may be further complicated by meningoencephalitis, myelopathy, vasculopathy and multiple ocular disorders. Importantly, these neurological and ocular complications of VZV reactivation can occur without rash. In such instances, virological verification relies on detection of VZV DNA or anti-VZV IgG antibody in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or less often, the presence of VZV DNA in blood mononuclear cells or anti-VZV IgM antibody in serum or CSF. If VZV were readily detected in other tissue samples (e.g., saliva or tears) in patients with neurological disease in the absence of rash and shown to correlate with the standard tests listed above, more invasive tests such as lumbar puncture might be obviated. In patients with acute herpes zoster, the yield of cell DNA was greater in saliva collected by passive drool or synthetic swab than by cotton swab. The time to process saliva from collection to obtaining DNA was one hour. VZV DNA was present exclusively in the pelleted fraction of saliva and was found in 100% of patients before antiviral treatment. This rapid sensitive method can be applied readily to saliva from humans with neurologic and other disease that might be caused by VZV in the absence of rash.

Keywords: saliva, varicella zoster virus, DNA, PCR

1. Introduction

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) is a human neurotropic alphaherpesvirus. Primary infection usually results in varicella (chickenpox), after which virus becomes latent in ganglionic neurons along the entire neuraxis. As cellular immunity to VZV wanes with age or immunosuppression, virus reactivates to produce herpes zoster (shingles), which is often complicated by postherpetic neuralgia, zoster paresis, cranial nerve palsies, myelitis, meningoencephalitis, vasculopathy and multiple serious ocular disorders (Gilden et al., 2000). Importantly, all of these conditions may develop in the absence of rash, making diagnosis difficult. In such instances, virological verification of disease produced by VZV relies on detection of VZV DNA or anti-VZV IgG antibody in cerebrospinal fluid or, less often, the presence of VZV DNA in blood mononuclear cells or anti-VZV IgM antibody in serum or CSF. Because VZV DNA is present in saliva of patients with acute zoster (Mehta et al., 2008), as well as in patients with zoster sine herpete (Hato et al., 2000), saliva might be helpful in diagnosing disease produced by VZV in the absence of rash.

Saliva obtained by cotton swab followed by DNA concentration using centrifugal filtration units revealed VZV DNA in all of 54 patients with acute herpes zoster before antiviral treatment (Mehta et al., 2008). In the present study, the yield of cell and VZV DNA in saliva collected by passive drool and synthetic swab was compared with that obtained by cotton swab, and tested whether a short (20 min) high-speed centrifugation of saliva might replace DNA concentration for 6 hours in centrifugal filtration units and still allow detection of VZV DNA.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

The Institutional Review Boards of the Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX and the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Houston, TX approved human study protocols. Informed consent was obtained from 26 zoster patients (19 men and 7 women) 22 to 78 years old (57±4 years; mean ± SD). Saliva was obtained from 17 patients before antiviral treatment and from 9 patients 3–7 days after antiviral treatment.

2.2 Collection of saliva, DNA extraction and quantitative PCR

Saliva was collected by three different methods: (1) passive drool, (2) synthetic polymer swab (Salimetrics, State College, PA, USA) and (3) cotton swab (Salivette; Sarstedt, Newton, NC, USA). For passive drool collection, individuals sat comfortably and allowed saliva to accumulate in the mouth after which saliva was allowed to flow into a wide-mouth polypropylene tube; the process was repeated until at least 2 ml of saliva was obtained. For collections using synthetic or cotton swabs, the swab was placed in the mouth until saturated with saliva. Saliva-saturated swabs were centrifuged at 1400 × g for 5 min, which collected saliva in the outer tube of the Salimetrics (synthetic swab) or Salivette (cotton swab) assembly. Saliva obtained after low speed centrifugation (synthetic or cotton swab), as well as saliva obtained by passive drool and vortexing, was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min and the pellet was re-suspended in 200 µl PBS. DNA was extracted from the re-suspended pellet with a QIA-Amp DNA kit (Qiagen; Germantown, MD, USA) (Mehta et al., 2004). DNA concentration was determined (NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer; NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), and real-time PCR was performed in triplicate to quantify the VZV DNA copy number using Taqman 7900 (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA). VZV DNA copy number standards were included in all reactions; the lower level of PCR sensitivity was 10 copies of VZV DNA per ng of salivary DNA. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in a TaqMan 7900 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems) using fluorescence-based amplification. The final concentration fro primers was 100 nmoles and for probes was 50 nmoles. VZV gene 63 DNA sequences (forward primer CGC GTT TTG TAC TCC GGG; reverse primer ACG GTT GAT GTC CTC AAC GAG; probe TGG GAG ATC CAC CCG GCC AG), and glyceraldehyde 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPdH) DNA sequences (forward primer CAA GGT CAT CCA TGA CAA CTT TG; reverse primer GGC CAT CCA CAG TCT TCT GG; probe ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC ACT GCC A) were used in PCR under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min denaturation and 40 cycles alternating between 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Collection methods were compared based on median values using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

3. Results

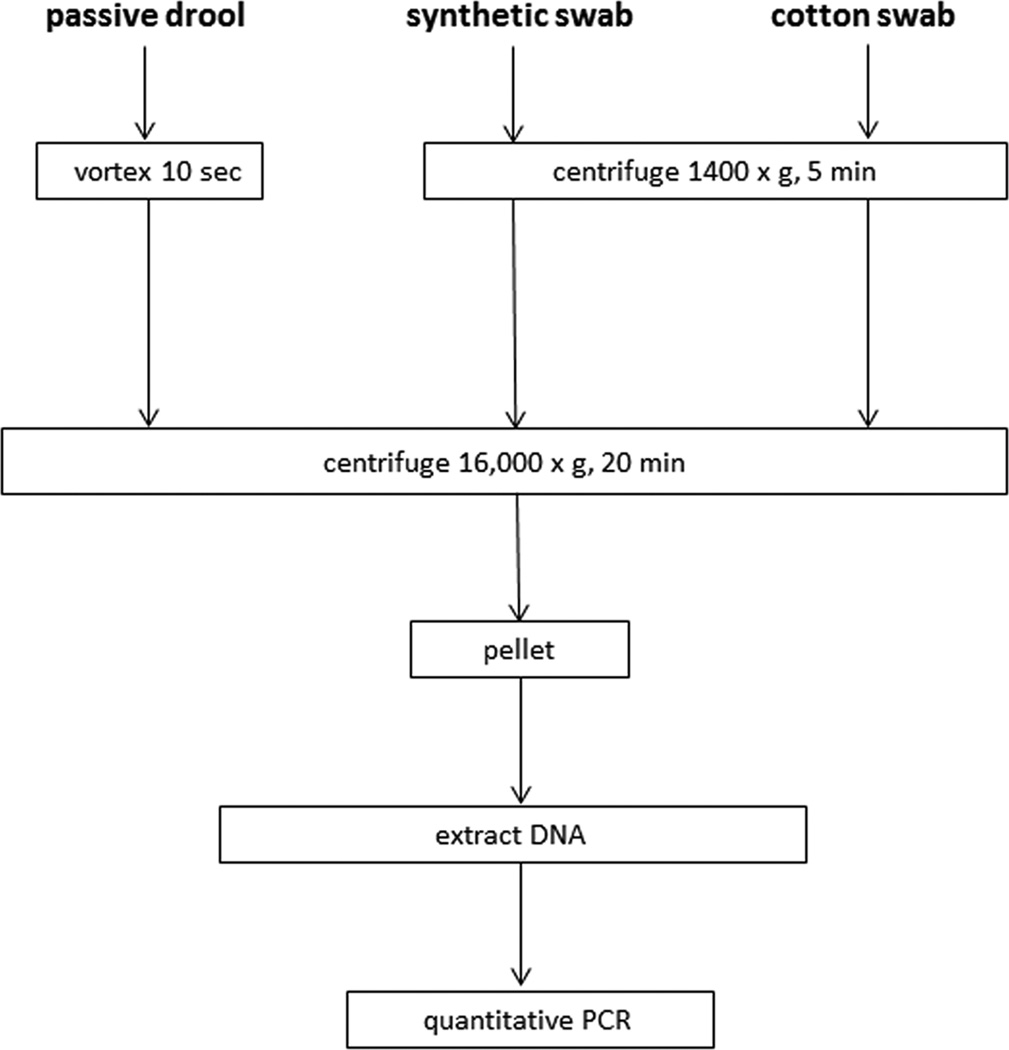

Saliva was collected from 26 zoster patients by three methods as outlined in Figure 1. The median DNA yield (Table 1) obtained by passive drool (800 ng) was 1.4-fold greater than that obtained by synthetic swab (580 ng) and 14.5-fold greater than that obtained by cotton swab (55 ng) (p<0.0001, signed-rank test for passive drool yield and synthetic vs. cotton swab yield).

Fig. 1. Saliva collection and processing.

Saliva was collected by passive drool, dispersed by vortexing and concentrated by high-speed centrifugation. Saliva was also collected in synthetic and cotton swabs, briefly centrifuged to separate saliva from swabs, and concentrated by high-speed centrifugation. Total DNA was extracted from polluted saliva and VZV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR.

Table 1.

DNA yield (ng) in the cell pellet of saliva collected by passive drool, synthetic swab and cotton swab from 26 patients with herpes zoster.

| patient | passive drool | synthetic swab | cotton swab |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 475 | 310 | 85 |

| 2 | 487 | 330 | 50 |

| 3 | 1490 | 625 | 55 |

| 4 | 1503 | 1105 | 90 |

| 5 | 362 | 155 | 80 |

| 6 | 369 | 245 | 35 |

| 7 | 684 | 335 | 95 |

| 8 | 644 | 235 | 80 |

| 9 | 1010 | 645 | 45 |

| 10 | 1012 | 745 | 70 |

| 11 | 779 | 655 | 140 |

| 12 | 1807 | 1205 | 45 |

| 13 | 640 | 405 | 30 |

| 14 | 643 | 258 | 25 |

| 15 | 615 | 453 | 25 |

| 16 | 587 | 631 | 35 |

| 17 | 904 | 311 | 40 |

| 18 | 854 | 751 | 45 |

| 19 | 1013 | 240 | 35 |

| 20 | 1005 | 775 | 40 |

| 21 | 904 | 705 | 20 |

| 22 | 893 | 745 | 80 |

| 23 | 527 | 282 | 105 |

| 24 | 1620 | 1205 | 210 |

| 25 | 820 | 645 | 65 |

| 26 | 620 | 535 | 95 |

| median | 800 | 580 | 55 |

| p25a | 615 | 310 | 35 |

| p75b | 1010 | 745 | 85 |

25th percentile

75th percentile

VZV DNA was detected in all 17 zoster patients whose saliva was collected before antiviral treatment by either passive drool or synthetic swab, but only in 13 of 17 zoster patients whose saliva was collected by cotton swab (Table 2). GAPdH DNA was amplified in DNA extracted from all saliva samples. No VZV DNA was detected in any of 9 zoster patients when saliva was collected 3-7 days after antiviral treatment by the three methods (data not shown). The average VZV DNA yield obtained from saliva collected by passive drool was 3-fold greater than that obtained by synthetic swab and 9-fold greater than that obtained by cotton swab and was found exclusively in the pelleted fraction of saliva.

Table 2.

VZV DNA copy number per nanogram DNA in cell pellet of saliva collected by passive drool, synthetic swab and cotton swab in 17 zoster patients before antiviral treatment.

| patient | passive drool | synthetic swab | cotton swab |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10000 | 1000 | 780 |

| 2 | 1800 | 140 | 120 |

| 3 | 100000 | 98000 | 10000 |

| 4 | 12000 | 10000 | 5000 |

| 5 | 1230 | 1000 | 540 |

| 6 | 1356 | 980 | 345 |

| 7 | 4325 | 4300 | 1200 |

| 8 | 5456 | 4500 | 1000 |

| 9 | 2700 | 2200 | 540 |

| 10 | 4500 | 3000 | 0 |

| 11 | 3400 | 3200 | 0 |

| 12 | 1000000 | 10000 | 120 |

| 13 | 580 | 135 | 0 |

| 14 | 320 | 100 | 0 |

| 15 | 3240 | 120 | 0 |

| 16 | 3200 | 430 | 350 |

| 17 | 258 | 187 | 0 |

| median | 3240 | 1000 | 345 |

| p25 a | 1356 | 187 | 0 |

| p75 b | 5456 | 4300 | 780 |

25th percentile

75th percentile

4. Discussion

The yields of cell DNA were significantly greater in saliva collected by passive drool and synthetic swab than in saliva obtained by cotton swab. Additionally, a short 20-min period of high-speed centrifugation of saliva instead of a 6-hr concentration using centrifugal filtration units still allowed detection of VZV DNA in saliva obtained by passive drool and synthetic swabs from all 17 patients with acute herpes zoster before antiviral treatment. Given the well-documented cell-associated nature of VZV, the detection of VZV DNA exclusively in the pelleted fraction of saliva was not surprising.

Overall, the ability to obtain greater quantities of cell DNA by passive drool and synthetic swab methods and to detect VZV DNA by brief high-speed centrifugation provides a rapid and sensitive method to test saliva for VZV DNA in humans with neurologic and other disease that might be caused by VZV in the absence of rash. For example, if repeated studies show that patients with neurological disease without rash that can be produced by VZV (e.g., vasculopathy, myelopathy or an ocular disorder) have VZV DNA or anti-VZV IgG antibody in CSF as well as VZV DNA in saliva, then the need for invasive lumbar punctures in such patients would be obviated. Finally, while passive drool is less expensive than synthetic swab, the latter must be used to obtain saliva from astronauts in space (Mehta et al., 2004) or in confined conditions encountered in Earth-based models that mimic stressful conditions experienced during spaceflight (Mehta et al., 2007; Stowe et al., 2008; Cohrs et al, 2009; Zwart et al., 2011).

HIGHLIGHTS.

A rapid sensitive method to obtain DNA from saliva allowed detection of VZV DNA in 100% of patients with acute herpes zoster before treatment

Passive drool and synthetic swab yielded abundant amounts of total DNA

High-speed centrifugation significantly reduced the time to process saliva from collection to obtaining DNA

VZV DNA was found exclusively in the pelleted fraction of saliva

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NASA grants 111-30-10-03, 111-30-10-06 to DLP and by Public Health Service grants AG032958 (D.G., R.J.C.) and AG006127 (D.G.) from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Marina Hoffman for editorial review and Lori DePriest for manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Satish K. Mehta, Email: satish.k.mehta@nasa.gov.

Stephen K. Tyring, Email: styring@ccstexas.com.

Randall J. Cohrs, Email: randall.cohrs@ucdenver.edu.

Don Gilden, Email: don.gilden@ucdenver.edu.

Alan H. Feiveson, Email: alan.h.feiveson@nasa.gov.

Kayla J. Lechler, Email: kayla.j.lechler@nasa.gov.

Duane L. Pierson, Email: duane.l.piersonl@nasa.gov.

References

- Cohrs RJ, Koelle DM, Schuette MC, Mehta S, Pierson D, Gilden DH, Hill JH. Asymptomatic alphaherpesvirus reactivation. In: Gluckman TR, editor. Herpesviridae: Viral Structure, Life Cycle and Infections. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2009. pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, LaGuardia JJ, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:635–645. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hato N, Kisaki H, Honda N, Gyo K, Murakami S, Yanagihara N. Ramsay Hunt syndrome in children. Ann. Neurol. 2000;48:254–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SK, Tyring SK, Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Leal MJ, Castro VA, Feiveson AH, Ott CM, Pierson DL. Varicella-zoster virus in the saliva of patients with herpes zoster. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;197:654–657. doi: 10.1086/527420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S, Crucian B, Pierson D, Sams C, Stowe R. Monitoring immune system function and reactivation of latent viruses in the artificial gravity pilot study. J. Gravit. Phys. 2007;14:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SK, Cohrs RJ, Forghani B, Zerbe G, Gilden DH, Pierson DL. Stress-induced subclinical reactivation of varicella zoster virus in astronauts. J. Med. Virol. 2004;72:174–179. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe RP, Yetman DL, Storm WF, Sams CF, Pierson DL. Neuroendocrine and immune responses to 16-day bed rest with realistic launch and landing G profiles. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2008;79:117–122. doi: 10.3357/asem.2205.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart SR, Mehta SK, Ploutz-Snyder R, Bourbeau Y, Locke JP, Pierson DL, Smith SM. Response to vitamin D supplementation during Antarctic winter is related to BMI, and supplementation can mitigate Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. J. Nutr. 2011;141:692–697. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.134742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]