Abstract

Nogo receptors (NgR) are a family of cell surface receptors that are broadly expressed in the mammalian brain. These receptors could serve as an inhibitory element in the regulation of activity-dependent axonal growth and spine and synaptic formation in the adult animal brain. Thus, through balancing the structural response to changing cellular and synaptic inputs, NgRs participate in constructing activity-dependent morphological plasticity. Psychostimulants have been well documented to induce morphological plasticity critical for addictive properties of stimulants, although underlying molecular mechanisms are poorly understood. In this study, we initiated a study to investigate the response of NgRs to a stimulant. We tested the effect of acute administration of amphetamine on protein expression of two principal NgR subtypes (NgR1 and NgR2) in the rat striatum, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and hippocampus. We found that a single injection of amphetamine induced a rapid and time-dependent decrease in NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the striatum and mPFC. A relatively delayed and time-dependent decrease in expression of the two receptors was seen in the hippocampus. The drug-induced decrease in NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the three forebrain regions was dose-dependent. A behaviorally active dose of the drug was required to trigger a significant reduction in NgR1 and NgR2 expression. These data indicate that NgRs are subject to the regulation by the stimulant. Amphetamine exposure exerts the inhibitory modulation of basal NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the key structures of reward circuits in vivo.

Keywords: NgR, reticulon 4 receptor, Nogo-66, stimulant, addiction, spine density, striatum, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus

1. Introduction

Nogo receptors (NgR), also known as Nogo-66 receptors and reticulon 4 receptors (RTN4R), belong to a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored and membrane-bound family of cell surface receptors (Zhang et al., 2008; McDonald et al., 2011). In the mammalian brain, these receptors are distributed in broad areas, including the striatum, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and hippocampus (Laurén et al., 2003; Hasegawa et al., 2005; Barrette et al., 2007). At the cellular level, NgRs are distributed densely in axonal, dendritic and spine membranes and in both pre-and postsynaptic density fractions (Lee et al., 2008; Raiker et al., 2010). Upon binding to myelin-associated neurite outgrowth inhibitory proteins (e.g., Nogo), NgRs restrict activity-dependent structural alterations at the synaptic level by blocking axonal outgrowth, dendritic arborization, spinogenesis, and/or synaptogenesis (Lee et al., 2008; Raiker et al., 2010; Zagrebelsky et al., 2010; Wills et al., 2012;). Through actively regulating spinogenesis and synaptogenesis in the adult brain, NgRs play an important role in synaptic plasticity (Raiker et al., 2010) and memory formation (Karlén et al., 2009).

NgR expression is subject to the activity-dependent modulation. In cultured hippocampal neurons, application of the agents that elevate neuronal activity, including KCl, NMDA and the GABA receptor antagonist, consistently reduced NgR mRNA and protein expression (Wills et al., 2012). In contrast, the agents that inhibit neuronal activity (the Na+ channel blocker and the NMDA receptor antagonist) enhanced NgR expression (Wills et al., 2012). In adult animals, kainate-induced seizure and enriched environment stimulation decreased NgR1 expression in the hippocampus in vivo (Josephson et al., 2003; Wills et al., 2012). It is suggested that enhanced neuronal activity may relieve the NgR-dependent barrier to synaptic growth and thus facilitate synaptogenesis during development and plasticity in the adult brain (Wills et al., 2012).

Psychostimulants are known to induce robust morphological changes at the spine and synaptic level in multiple brain regions (Robinson and Kolb, 2004). This long-lasting structural plasticity contributes to the enduring remodeling of excitatory synapses and stimulant addiction (Abraham, 2008; Shen et al., 2009). As an experience-dependent disorder involving reward and learning and memory, drug addiction is believed to be closely linked to neural activities in the striatum, mPFC and hippocampus (Belujon and Grace, 2011). In fact, substantial structural changes occur in these regions in response to stimulant exposure. For instance, prenatal cocaine exposure increased the dendritic spine density in medium spiny neurons of the striatum, layer II/III of the mPFC, and CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus in postnatal rats (Frankfurt et al., 2009). Chronic cocaine or amphetamine (AMPH) also induced similar changes in the rat striatum and mPFC (Robinson and Kolb, 1999). While these morphological changes are thought to mediate stimulant effects, molecular mechanisms underlying these changes are poorly understood. NgRs are key regulators of morphological plasticity. Their adaptive changes in response to stimulant exposure may constitute an attractive metaplastic basis for the morphological effect of stimulants.

We therefore initiated the present study to investigate the response of NgRs to the stimulant AMPH. We investigated possible changes in basal protein expression of two major subtypes of NgRs (NgR1 and NgR2) in the striatum, mPFC, and hippocampus of adult rat brains in response to acute AMPH administration in vivo. Both time-course and dose-response experiments were carried out to characterize the effect of AMPH.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male Wistar rats weighing 250–300 g from Charles River (New York, NY) were individually housed in a controlled environment at a constant temperature of 23°C and humidity of 50 ± 10% with food and water available ad libitum. The animal room was on a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle. Rats were allowed 5–6 days of habituation to the animal colony. All animal use and procedures were in strict accordance with the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Systemic drug injection

D-amphetamine sulfate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The drug was freshly prepared by dissolving it into 0.9% saline solution before experiments. In time-course experiments, rats received a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of AMPH at a dose of 5 mg/kg. The rats were then sacrificed at a different time point (0.5, 1, 2, or 4 h) after drug injection for the following immunoblot analysis of changes in NgR expression. A separate time-course study was added to test the effect of AMPH (5 mg/kg, i.p.) at 8 h after the drug injection. In dose-response experiments, rats were given a single injection of AMPH at different doses (0.2, 1, or 5 mg/kg, i.p.). These rats were sacrificed 4 h after drug injection for detecting the effect of AMPH on NgR expression. Rats treated with saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.) served as controls. To harvest brain tissue for immunoblot analysis, rats were anesthetized with equithesin (5 ml/kg, i.p.) and decapitated. Brains were removed and cut into coronal sections. Three forebrain regions, including the striatum, mPFC and hippocampus, were dissected. Brain tissue was homogenized in the isotonic sucrose homogenization buffer containing 0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY) in a glass grinding vessel with a motor driven Teflon pestle at 700 rpm. The homogenate was centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Pellets were dissolved in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Thermo Scientific) with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentrations were determined with a Pierce BCA assay kit.

2.3. Western blot analysis

Western blot was performed as described previously (Guo et al., 2010). Briefly, the equal amount of proteins was separated on SDS NuPAGE Novex 4–12% gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Proteins were transferred to the polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and blocked in blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h. Blots were washed and incubated in the blocking buffer containing an indicated primary rabbit antibody. Antibodies used in the present study include rabbit antibodies against β-actin (1:4,000, Sigma), and mouse antibodies against NgR1 (1:1,000, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or NgR2 (1:1,000, R&D Systems). Both NgR1 and NgR2 antibodies have been pre-validated for their specificity for the targets (Wills et al., 2012). The primary antibody incubation was carried out overnight at 4°C and followed by 1 h incubation in a horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody against rabbit (1:5,000) or mouse (1:3,000). Immunoblots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). MagicMark XP Western protein standards (Invitrogen) were used for protein size determination. The density of immunoblots was measured using the Kodak 1D Image Analysis software.

2.4. Data analysis

The results were presented as means ± S.E.M. Data were analyzed using Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a Bonferroni comparison of groups. Probability levels of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

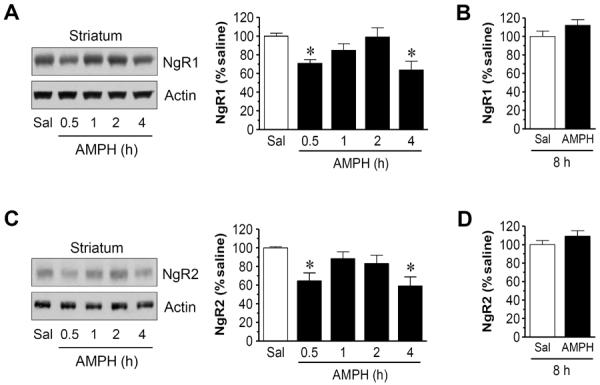

3.1. Time-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the striatum

To determine whether acute AMPH administration time-dependently alters basal expression of NgR1 and NgR2 in the striatum, we subjected rats to a single dose of AMPH (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and we then sacrificed rats at a different time point (0.5, 1, 2, or 4 h) after drug injection. Changes in striatal NgR1 and NgR2 protein abundance were analyzed using Western blot. AMPH induced a significant decrease in NgR1 levels at an early time point (0.5 h after drug injection) (70.9 ± 3.9% of saline, P < 0.05; Fig. 1A). However, a significantly less or no decrease in NgR1 expression was seen at 1 or 2 h, respectively. At 4 h, AMPH again produced a marked reduction of NgR1 (63.9 ± 9.2% of saline, P < 0.05). Due to this reduction, we carried out a separate experiment to evaluate the effect of AMPH at a longer time point. As shown in Fig. 1B, AMPH at 8 h after injection caused no evident changes in NgR1 expression. Like NgR1, NgR2 expression in the striatum was reduced 0.5 h after AMPH administration (64.5 ± 8.7% of saline, P < 0.05; Fig. 1C). This reduction became no significant at 1 and 2 h. A significant reduction reoccurred at 4 h (59.3 ± 9.5% of saline, P < 0.05; Fig. 1C) and then returned to the control level at 8 h (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that both NgR1 and NgR2 expression in striatal neurons is sensitive to AMPH. These receptors noticeably undergo two phases of downregulation (early and late components) in response to the drug.

Figure 1.

Time-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the rat striatum. (A and B) Effects of AMPH on NgR1 expression at a range of time points (0.5-4 h, A) or 8 h (B) after drug injection. (C and D) Effects of AMPH on NgR2 expression at a range of time points (0.5-4 h, C) or 8 h (D) after drug injection. Representative immunoblots are shown left to the quantification of immunoblots (A and C). Rats were treated with a single dose of AMPH (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and were sacrificed at time points indicated. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n = 4-5 per group) and were analyzed using ANOVA (A and C) or Student's t test (B and D). *P < 0.05 versus saline (Sal).

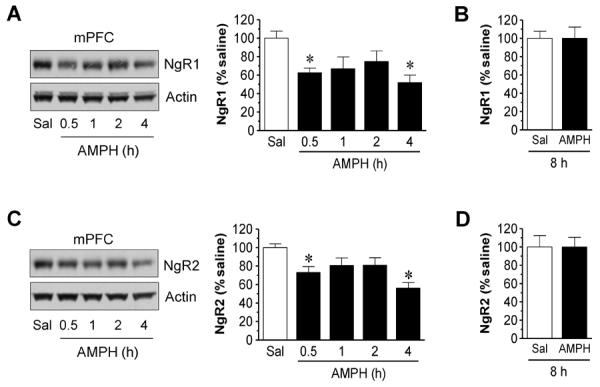

3.2. Time-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the mPFC and Hippocampus

We next investigated the effect of AMPH on NgR expression in the mPFC. Like the striatum, NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the mPFC was reduced in AMPH-treated rats compared to saline-treated rats. The time course of these changes resembled that seen in the striatum (Fig. 2). Thus, NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the mPFC was also subject to the downregulation by AMPH.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the rat mPFC. (A and B) Effects of AMPH on NgR1 expression at a range of time points (0.5-4 h, A) or 8 h (B) after drug injection. (C and D) Effects of AMPH on NgR2 expression at a range of time points (0.5-4 h, C) or 8 h (D) after drug injection. Representative immunoblots are shown left to the quantification of immunoblots (A and C). Rats were treated with a single dose of AMPH (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and were sacrificed at time points indicated. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n = 4-5 per group) and were analyzed using ANOVA (A and C) or Student's t test (B and D). *P < 0.05 versus saline (Sal).

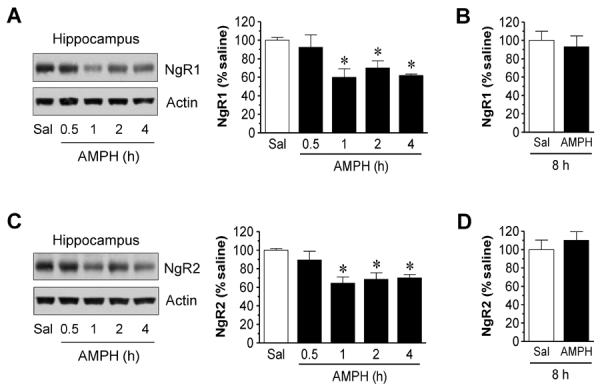

In the hippocampus, we found that NgR1 was not altered 30 min after drug injection (Fig. 3A). Only at 1 h, were NgR1 levels reduced in AMPH-treated rats compared to saline-treated rats (59.8 ± 9.3% of saline, P < 0.05). This reduction remained significant at 2 and 4 h (Fig. 3A) and returned to the normal level at 8 h (Fig. 3B). NgR2 expression in the hippocampus also showed a delayed decrease at 1 h (64.6 ± 6.6% of saline, P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). The receptor level remained reduced at 2 and 4 h. At 8 h, NgR2 levels in AMPH-treated rats were not different from those in saline-treated animals (Fig. 3D). Thus, instead of a rapid decline seen in the striatum and mPFC, a relatively delayed decrease in NgR1 and NgR2 expression was seen in the hippocampus after AMPH administration.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the rat hippocampus. (A and B) Effects of AMPH on NgR1 expression at a range of time points (0.5-4 h, A) or 8 h (B) after drug injection. (C and D) Effects of AMPH on NgR2 expression at a range of time points (0.5-4 h, C) or 8 h (D) after drug injection. Representative immunoblots are shown left to the quantification of immunoblots (A and C). Rats were treated with a single dose of AMPH (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and were sacrificed at time points indicated. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n = 4-5 per group) and were analyzed using ANOVA (A and C) or Student's t test (B and D). *P < 0.05 versus saline (Sal).

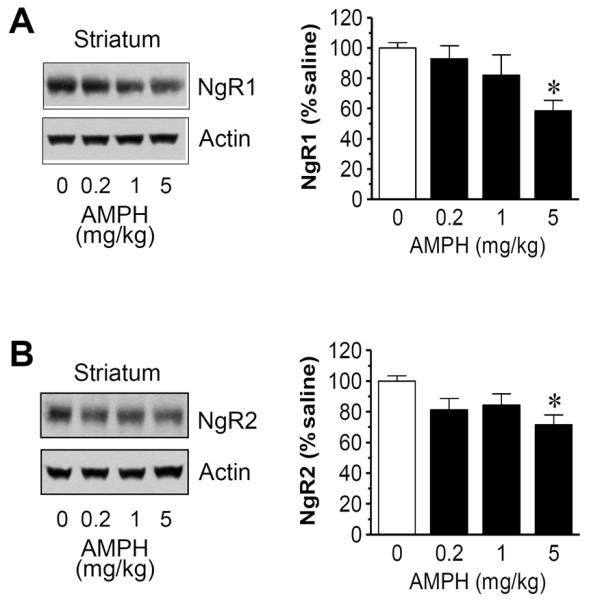

3.3. Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the striatum

We next carried out a study to define the dose-dependent effect of AMPH. In this study, rats received a single injection of saline or AMPH at a different dose (0.2, 1, or 5 mg/kg, i.p.). They were then sacrificed 4 h after drug injection for immunoblot analysis of changes in NgR expression in three brain regions. In the striatum, a clear dose-dependent effect of AMPH on NgR1 expression was observed. As shown in Fig. 4A, lower doses of AMPH (0.2 and 1 mg/kg) caused minimal changes in NgR1 expression. In contrast, a higher dose of AMPH (5 mg/kg) induced a significant decrease in NgR1 levels (58.5 ± 6.9% of saline, P < 0.05). Similar to NgR1, NgR2 underwent a dose-dependent decrease in its protein abundance. Significant reduction of NgR2 was seen after AMPH injection at 5 mg/kg (71.6 ± 6.3% of saline, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that AMPH reduces NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the striatum in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 4.

Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the rat striatum. (A) Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on striatal NgR1 expression. (B) Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on striatal NgR2 expression. Representative immunoblots are shown left to the quantification of immunoblots. Rats were treated with saline or AMPH at different doses (0.2, 1, or 5 mg/kg, i.p.) and were sacrificed 4 h after drug injection. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n = 5 per group) and were analyzed using ANOVA. *P < 0.05 versus saline.

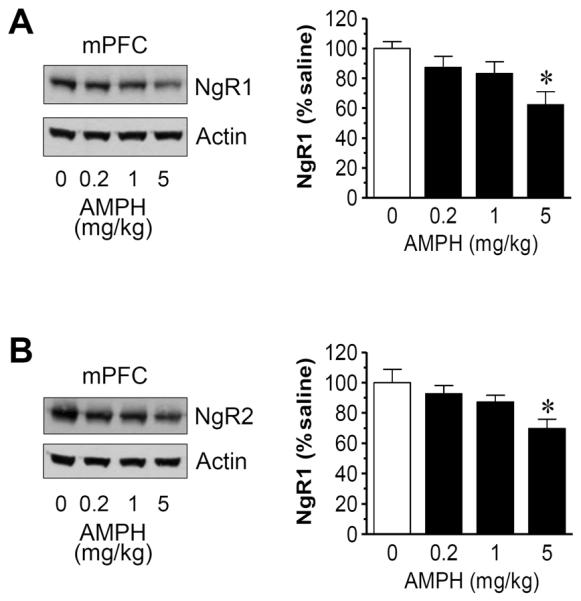

3.4. Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the mPFC and hippocampus

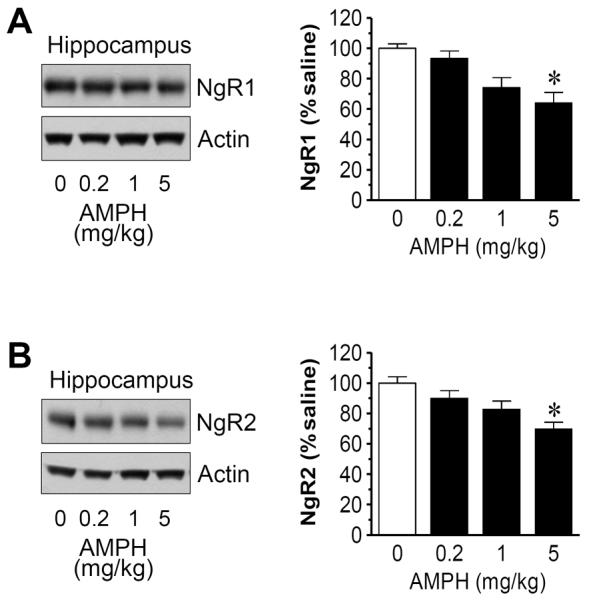

We then used the brain tissue dissected from the mPFC and hippocampus to analyze changes in NgR expression in response to different doses of AMPH. In the mPFC, AMPH at 5 mg/kg but not the two lower doses reduced NgR1 expression to a significant level (62.4 ± 8.8% of saline, P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). The drug at this dose also significantly reduced NgR2 expression (69.8 ± 6.2% of saline, P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B). In the hippocampus, similar dose-dependent responses of NgR1 and NgR2 to AMPH were observed (Fig. 6). These data define the mPFC and hippocampus as central sites where NgR1 and NgR2 expression can be dose-dependently downregulated by AMPH.

Figure 5.

Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the rat mPFC. (A) Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on mPFC NgR1 expression. (B) Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on mPFC NgR2 expression. Representative immunoblots are shown left to the quantification of immunoblots. Rats were treated with saline or AMPH at different doses (0.2, 1, or 5 mg/kg, i.p.) and were sacrificed 4 h after drug injection. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n = 5 per group) and were analyzed using ANOVA. *P < 0.05 versus saline.

Figure 6.

Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the rat hippocampus. (A) Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on hippocampal NgR1 expression. (B) Dose-dependent effects of AMPH on hippocampal NgR2 expression. Representative immunoblots are shown left to the quantification of immunoblots. Rats were treated with saline or AMPH at different doses (0.2, 1, or 5 mg/kg, i.p.) and were sacrificed 4 h after drug injection. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n = 5 per group) and were analyzed using ANOVA. *P < 0.05 versus saline.

4. Discussion

Neuronal expression of NgRs is sensitive to many experimental manipulations. In general, their expression in hippocampal neurons was downregulated when neuronal activity was enhanced by NMDA glutamate receptor activation, GABA receptor inhibition, or kainate seizure (Josephson et al., 2003; Wills et al., 2012). In contrast, when neuronal activity was inhibited by pharmacological blockade of Na+ channels or NMDA receptors, NgR expression was upregulated in hippocampal neurons (Wills et al., 2012). The results from this study add the stimulant as an exogenous agent that significantly inhibits constitutive expression of both NgR1 and NgR2 subtypes in the hippocampus. Additionally, the inhibition of NgR expression occurred in the mPFC and striatum. NgR1 and NgR2 mRNAs and proteins were densely expressed in the mPFC and hippocampus (Laurén et al., 2003; Hasegawa et al., 2005; Venkatesh et al., 2005; Barrette et al., 2007). In the striatum, while NgR2 mRNAs and proteins were seen in this region, NgR1 mRNAs were absent (Laurén et al., 2003; Hasegawa et al., 2005; Venkatesh et al., 2005; Barrette et al., 2007). However, NgR1 proteins were detected in the striatum, possibly residing on incoming axons (Venkatesh et al., 2005; this study). Thus, AMPH is believed to affect the axonal pool of NgR1 proteins within the striatum.

AMPH rapidly reduced striatal and cortical NgR1/2 protein levels at 0.5 h after injection. In contrast, AMPH produced a relatively delayed reduction of both receptors in the hippocampus. This kinetic disparity may lie on different anatomical, neurochemical and physiological properties of these brain regions and their discrete responses to AMPH. Additionally, in the detailed time-course study, NgR1/2 in the striatum and mPFC showed an early and a delayed decrease at respective 0.5 and 4 h time points. While the reasons for these separate decreases are unclear, they may reflect distinct mechanisms involved in the early and late reduction or different subsynaptic pools of the receptor affected by AMPH. Finally, it is noticeable that two major NgR subtypes, NgR1 and NgR2, were consistent to each other in their time- and dose-dependent responses to AMPH in all three brain regions surveyed. This implies that the two receptors may work in concert with each other to regulate morphological responses to the drug. An early study also showed comparable decreases in both NgR1 and NgR2 expression in hippocampal neurons in response to experimentally increased neuronal activity (Wills et al., 2012).

NgRs serve as inhibitory regulators of structural development and plasticity (Zhang et al., 2008; McDonald et al., 2011). Earlier NgR studies focused on their inhibitory roles in axon outgrowth. The NgR is a co-receptor bound by a discrete set of protein ligands, including Nogo-A, MAG (myelin-associated glycoprotein), OMgp (oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein), FGF1 (fibroblast growth factor 1), and FGF2 (Lee et al., 2008). Some of these ligands were isolated from myelin. Thus, NgRs are involved in growth-cone collapse and axon retraction following brain injury (Yiu and He, 2006). Recently, evidence shows that NgRs are located at dendritic spines and synaptic membranes and regulate synaptic structural plasticity (Lee et al., 2008; Raiker et al., 2010). NgR1 mutant mice exhibited a substantial increase in stubby spines and fewer mushroom-shaped and thin spines compared with wild-type controls (Lee et al., 2008). The direct link between downregulated NgRs and increased dendritic spine/synaptic density was revealed in the mouse hippocampus in vivo (Wills et al., 2012). Loss of NgR1, NgR2, or NgR3 led to an increase in the number of synapses in vitro, whereas loss of all three was necessary for increased synaptogenesis in the hippocampus in vivo (Wills et al., 2012). Thus, NgRs act on both axonal and dendritic sites and restrict axonal growth as well as dendritic spine and synaptic formation.

Drug addiction is a progressive process of experience-dependent neuroplasticity which traditionally involves the key structures in the dopamine responsive reward circuit, such as the striatum and mPFC (Hyman et al., 2006; Belujon and Grace, 2011). Increasing evidence has also broadened our view to additional neural substrates (Gardner, 2011). The hippocampus is particularly interesting in this regard and receives increasing attention for its role in drug addiction (Belujon and Grace, 2011). In all these regions, dramatic and enduring morphological changes at spine and synaptic sites occur in response to stimulant exposure (Robinson and Kolb, 1999; Robinson and Kolb, 2004; Frankfurt et al., 2009; Dumitriu et al., 2012). These plastic changes contribute to the remodeling of excitatory synapses, constituting the metaplastic basis for the addictive property of stimulants. While the occurrence of morphological plasticity in these brain regions is obvious, molecular mechanisms underlying the development of structural plasticity are less clear (Dietz et al., 2009). In this study, we found that NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the striatum, mPFC and hippocampus was downregulated by AMPH. This provides an attractive mechanism processing drug-stimulated morphological changes. Given the fact that NgRs suppress activity-dependent structural changes, the downregulation of their abundance may translate to a corresponding decrease in their inhibitory function, leading to increases in the number of dendritic branches and the density of dendritic spines on striatal medium spiny neurons and prefrontal cortical neurons following amphetamine and/or cocaine administration as reported previously (Robinson and Kolb, 1997; 1999; Robinson et al., 2001; Li et al., 2003). However, the causal linkage of the downregulated NgR expression to morphological plasticity was not explored in this study. This linkage together with the responsiveness of NgRs to chronic treatment with stimulants (such as self-administration of stimulants) remains interesting topics in the future investigation. In addition, the NgR downregulation was reversed within 8 h after AMPH injection. How this reversible nature in response to a single dose of AMPH leads to persistent downstream morphological plasticity is unclear. It is likely that repeated AMPH administration or self-administration of the drug causes different temporal changes in NgR expression, which are closely linked to structural and behavioral responses to AMPH administered in these regimens.

5. Conclusions

This study initiated an effort to define the responsiveness of brain NgRs to AMPH. We found that NgRs in several forebrain regions are sensitive targets of the drug. Acute injection of AMPH induced a time- and dose-dependent decrease in NgR1 and NgR2 expression in the rat striatum. Similar results were obtained in the mPFC and hippocampus. These results indicate that NgRs in these brain regions are subject to the downregulation in response to dopamine stimulation by AMPH.

Highlights

Amphetamine reduces Nogo receptor expression in the rat striatum in a time-dependent manner.

Amphetamine reduces Nogo receptor expression in the striatum in a dose-dependent manner.

Amphetamine reduces Nogo receptor expression in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants DA010355 (J.Q.W.) and MH061469 (J.Q.W.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Abraham WC. Metaplasticity: tuning synapses and networks for plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:387–399. doi: 10.1038/nrn2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrette B, Vallières N, Dubé M, Lacroix S. Expression profile of receptors for myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the intact and injured mouse central nervous system. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;34:519–538. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belujon P, Grace AA. Hippocampus, amygdala, and stress: interacting systems that affect susceptibility to addiction. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1216:114–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz DM, Dietz KC, Nestler EJ, Russo SJ. Molecular mechanisms of psychostimulant-induced structural plasticity. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42:S69–S78. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu D, Laplant Q, Grossman YS, Dias C, Janssen WG, Russo SJ, Morrison JH, Nestler EJ. Subregional, dendritic compartment, and spine subtype specificity in cocaine regulation of dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:6957–6966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5718-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt M, Wang HY, Marmolejo N, Bakshi K, Friedman E. Prenatal cocaine increases dendritic spine density in cortical and subcortical brain regions of the rat. Dev. Neurosci. 2009;31:71–75. doi: 10.1159/000207495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL. Addiction and brain reward and antireward pathways. Adv. Psychosom. Med. 2011;30:22–60. doi: 10.1159/000324065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo ML, Fibuch EE, Liu XY, Choe ES, Buch S, Mao LM, Wang JQ. CaMKIIalpha interacts with M4 muscarinic receptors to control receptor and psychomotor function. EMBO J. 2010;29:2070–2081. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, Ohno K, Sano M, Omura T, Omura K, Nagano A, Sato K. The differential expression patterns of messenger RNAs encoding Nogo-A and Nogo-receptor in the rat central nervous system. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;133:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson A, Trifunovski A, Schéele C, Widenfalk J, Wahlestedt C, Brené S, Olson L, Spenger C. Activity-induced and developmental downregulation of the Nogo receptor. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlén A, Karlsson TE, Mattsson A, Lundströmer K, Codeluppi S, Pham TM, Bäckman CM, Ogren SO, Aberg E, Hoffman AF, Sherling MA, Lupica CR, Hoffer BJ, Spenger C, Josephson A, Brené S, Olson L. Nogo receptor 1 regulates formation of lasting memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:20476–20481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurén J, Airaksinen MS, Saarma M, Timmusk T. Two novel mammalian Nogo receptor homologs differentially expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003;24:581–594. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Raiker SJ, Venkatesh K, Geary R, Robak LA, Zhang Y, Yeh HH, Shrager P, Giger RJ. Synaptic function for the Nogo-66 receptor NgR1: regulation of dendritic spine morphology and activity-dependent synaptic strength. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2753–2765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5586-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kolb B, Robinson TE. The location of persistent amphetamine-induced changes in the density of dendritic spines on medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens and caudate-putamen. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1082–1085. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CL, Bandtlow C, Reindl M. Targeting the Nogo receptor complex in diseases of the central nervous system. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011;18:234–244. doi: 10.2174/092986711794088326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiker SJ, Lee H, Baldwin KT, Duan Y, Shrager P, Giger RJ. Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein and Nogo negatively regulate activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:12432–12445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0895-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Gorny G, Mitton E, Kolb B. Cocaine self-administration alters the morphology of dendrites and dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens and neocortex. Synapse. 2001;39:257–266. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010301)39:3<257::AID-SYN1007>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Persistent structural modifications in nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex neurons produced by previous experience with amphetamine. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:8491–8497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08491.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Alterations in the morphology of dendrites and dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex following repeated treatment with amphetamine or cocaine. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:1598–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Structural plasticity associated with exposure to drugs of abuse. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HW, Toda S, Moussawi K, Bouknight A, Zahm DS, Kalivas PW. Altered dendritic spine plasticity in cocaine-withdrawn rats. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:2876–2884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5638-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh K, Chivatakarn O, Lee H, Joshi PS, Kantor DB, Newman BA, Mage R, Rader C, Giger RJ. The Nogo-66 receptor homolog NgR2 is a sialic acid-dependent receptor selective for myelin-associated glycoprotein. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:808–822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4464-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills ZP, Mandel-Brehm C, Mardinly AR, McCord AE, Giger RJ, Greenberg ME. The nogo receptor family restricts synapse number in the developing hippocampus. Neuron. 2012;73:466–481. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiu G, He Z. Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:617–627. doi: 10.1038/nrn1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagrebelsky M, Schweigreiter R, Bandtlow CE, Schwab ME, Korte M. Nogo-A stabilizes the architecture of hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:13220–13234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1044-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhang Q, Zhang JH, Qin X. NgR acts as an inhibitor to axonal regeneration in adults. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2030–2040. doi: 10.2741/2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]