Abstract

High fidelity genome-wide expression analysis has strengthened the idea that microRNA (miRNA) signatures in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) can be potentially used to predict the pathology when anatomical samples are inaccessible like heart. PBMCs from 48 non-failing controls and 44 patients with relatively stable chronic heart failure (ejection fraction of ≤ 40%) associated with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) were used for miRNA analysis. Genome-wide miRNA-microarray on PBMCs from chronic heart failure patients identified miRNA signature uniquely characterized by the downregulation of miRNA-548 family members. We have also independently validated downregulation of miRNA-548 family members (miRNA-548c & 548i) using real time-PCR in a large cohort of independent patient samples. Independent in silico Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) of miRNA-548 targets shows unique enrichment of signaling molecules and pathways associated with cardiovascular disease and hypertrophy. Consistent with specificity of miRNA changes with pathology, PBMCs from breast cancer patients showed no alterations in miRNA-548c expression compared to healthy controls. These studies suggest that miRNA-548 family signature in PBMCs can therefore be used as to detect early heart failure. Our studies show that cognate networking of predicted miRNA-548 targets in heart failure can be used as a powerful ancillary tool to predict the ongoing pathology.

Keywords: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC), microRNA-548, dilated cardiomyopathy, canonical signaling networks, biomarker

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are 18–25-nucleotide long, non-coding RNAs that regulate the gene expression by binding to mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner resulting in degradation or translational inhibition of targeted transcripts [1-3]. miRNAs are known to regulate ~30% total mRNA suggesting that they may play an important role in many cellular functions [4] including regulation of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure [5-10]. We and others have shown that end-stage human dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is associated with specific miRNA signature [11, 12] indicating that the molecular changes mediated by altered miRNAs could be integral to pathology. Reproducible miRNA expression pattern observed in lung cancer lead to the proposition that miRNA signature in diseased tissue can be used for diagnosis and assessing the progression of pathology [13, 14]. Use of tissue miRNA signature for disease diagnosis is a powerful tool when tissue is easily accessible but not in cases where it is inaccessible like the heart. Therefore, it becomes imperative to develop alternative high fidelity surrogate readouts for determining cardiac dysfunction.

Circulating biomarkers for congestive heart failure like brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), pro-BNP, C-reactive protein (CRP), cardiac troponins or atrial natriuretic peptide [15-22] have been extensively investigated. Despite high clinical and diagnostic value of these biomarkers, a lot still remains desired with regards to the early detection of cardiac disease. In this context, miRNAs can potentially provide a window of early detection of cardiac dysfunction. Recent studies have shown the role of circulating miRNAs as biomarkers and communicators of cardiovascular disease [23]. Circulating miRNAs in plasma from patients with unstable (acute myocardial infarction) [24], [25], stable coronary artery disease [26] and congestive heart failure [27] are promising biomarkers as there are alterations in specific miRNAs. A caveat with plasma miRNAs is their tissue of origin thus, analysis of miRNAs from peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMCs) will potentially overcome this issue providing high fidelity miRNA signature in conditions of cardiac pathology. Therefore, in light of the existing concerns, we decided to assess miRNA signature in circulating PBMCs.

Gene expression studies on PBMCs isolated from patients with chronic diseases like pediatric immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), psychiatric disorders or chronic fatigue syndrome [28-31] had expression profiles that were specific to the pathology. Furthermore, a recent study indicates that miRNAs in PBMCs from end-stage heart failure patients are altered compared to the non-failing controls [11]. Instead of end-stage heart failure patients, we have used DCM patients (NYHA class II/III (early heart failure)) to test whether earlier stages of cardiac dysfunction and failure can generate a specific miRNA signature reflecting the ongoing cardiac pathology. We observed a unique PBMC miRNA signature characterized by significant downregulation of miRNA-548 family members and representative members were validated using real time-PCR on an independent patient sample set. Furthermore, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of the predicted targets for miRNA-548 revealed cardiac hypertrophy as the top toxicity function associated with signaling networks. Our study has identified miRNA-548 family in PBMCs as a potential novel predictor of cardiac dysfunction which is further supported by independent network and pathway analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This study has been approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institution Review Board and all subjects provided written informed consent. We prospectively identified ambulatory subjects with chronic stable heart failure with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with no identifiable or reversible etiology (so-called “idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy”). Subjects demonstrated persistent (>3 months) left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LV ejection fraction ≤40%) as assessed by echocardiography to be classified as patients with DCM for the study. Control subjects included prospectively recruited, apparently healthy subjects with no known heart, kidney, lung, or hematologic disorders, and no evidence of cardiomyopathy as confirmed by echocardiography after enrollment. Control patients were recruited from the hospital population thus belonging to the similar demographics as the patients. The research staff was blinded on the status of the patients. The study included 48 non-failing controls and 44 patients, off which PBMCs from 7 non-failing and 7 patients with DCM were used for genome-wide miRNA microarray study. The miRNA-548 members were validated in an independent set of 41 non-failing and 37 failing patient samples. Consistent with the DCM phenotype in the patients, there was significant increase in BNP levels. Although CRP levels were increased in patients, it was not significantly different between the groups. Additionally, a subset of 10 patients, prospectively identified with coronary artery disease with no apparent heart failure (LV ejection fraction ~ 59.6%) were used to determine the specificity of the miRNA-548c signature in PBMCs for heart failure phenotype. Furthermore, to test the uniqueness of miRNA-548c signature in PBMC for the DCM phenotype, we have used breast cancer patients who have not been previously on any medications for our real time PCR studies.

Cell Isolation and preparation

After informed consent, venous blood samples were collected into sodium heparin-containing vacutainers. PBMCs were isolated from whole blood utilizing Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, counted, washed and resuspended in complete media (RPMI-1640 [Cleveland Clinic, Central Services Media Lab] with 10% bovine serum [Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD], 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 2mM L-glutamine, 25mM HEPES) containing 10% DMSO at a concentration of 10×106 cells/mL. PBMCs were then frozen in 1mL aliquots and transferred to a liquid nitrogen freezer until analysis. Plasma BNP and high sensitivity CRP levels were measured by Architect ci8200 platform (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL).

Quantitation of miRNA

Frozen PBMCs were thawed on ice and total RNA was isolated by Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). The concentration of RNA was determined by spectrophotometer and 2 μg of RNA was used for reverse transcription with reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) using specific primer sets as supplied with the Taqman assay kits for individual miRNAs. Quantitative real time PCR was done using cDNA with Taqman real time mix in a BioRad iCycler machine. The fold change in the miRNA levels was determined using RNU6B as an internal control. ΔΔCt method [32] was used to compare the DCM samples against the normal controls.

miRNA Microarray gene expression profiling

RNA isolated with TRIzol method (Invitrogen) was subjected to RNA labeling and hybridized on a custom designed miRNA microarray chip version 6 (microRNACHIPv6) as previously described [33]. Briefly, 2-5 μg of total RNA from each sample was biotin-labeled by reverse transcription using 5′ 2 X biotin end-labeled random octamer oligo. Hybridization of biotin-labeled cDNA to miRNA-specific probes was carried out on a miRNA microarray chip (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Version 6.0), which contains 3060 miRNA probes, designed from 948 human and 590 mouse miRNA genes (Sanger miRBase Version 15.0), in duplicate. Hybridization signal intensity of probes was detected by biotin binding of a Streptavidin–Alexa647 conjugate using Axon Scanner 4000B (Molecular Device, CA). The images were quantified by GENEPIX 6.0 software (Axon Instruments).

Computational Analysis of miRNA microarray data

Microarray images were analyzed by GenePix Pro as previously described [11]. Briefly, average values of the replicate spots for each miRNA were background-subtracted, normalized, and subjected to further analysis. The average expression values were log2-transformed and normalized using quantile normalization scheme. Medians of all samples were baseline transformed. The normalization and transformation of the heart microarray data was carried out using GeneSpring GX (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Differentially expressed miRNAs between control and DCM were identified using unpaired “t” test procedure with 0.05 as the cut-off for significance. Following identification of differentially expressing miRNAs, the experimentally verified and predicted targets for these altered miRNAs were subjected to microRNA Target Filter in Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) software (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA).

Network Analysis

Network analysis was carried out as previously described [11]. Briefly, dataset containing genes and the corresponding expression values were uploaded into the IPA algorithm and the molecules of our interest (identified targets of altered miRNA) were designated as focus molecules. These molecules, interacting with other molecules in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base, identified as network-eligible molecules. Network-eligible molecules serve as “seeds” for generating networks. Networks of the focus molecules are then algorithmically generated to maximize the connectivity between the focus molecules and other network-eligible molecules in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. The networks are represented using graphs. Genes or gene products are represented as nodes in the graphs, and the biological relationship between two nodes is represented as an edge. Nodes are displayed using various shapes that represent the functional class of the gene product. All edges are supported by at least one reference from literature, textbook, or from canonical information stored in the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base. Edges are displayed with various labels that describe the nature of the relationship between the nodes. A defined network is set to have a maximum of 35 molecules, and the additional molecules from the Ingenuity Knowledge Base are used to connect networks resulting in large merged networks.

Canonical Pathway and Functional Analysis

Canonical pathway analysis was carried out as previously described [11]. Briefly, pathway analysis was carried out using the library of canonical pathways in IPA by analyzing the targets of altered miRNA identified using microRNA Target Filter in IPA. These target genes (focus genes) were analyzed for over-represented canonical pathways in control and diseased human samples. Significance of association between these genes and the canonical pathway was measured in two ways as follows: (a) ratio of the number of focus genes that are mapped to the pathway to the total number of genes involved in the canonical pathway, and (b) “p” value obtained using Fischer’s exact test determining the probability that the association between the focus genes and the canonical pathway is explained by chance alone. Functional analysis of a network identified the biological functions that were most significant to the miRNA-548 targets in the network. Using these genes in the network, toxicity functions were analyzed using the IPA Tox function algorithm.

Statistical analysis

Distribution of the raw data was checked using histograms. Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was performed. Data was log2 transformed and tested on normality. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis was performed by use of correlation based distance and average linkage on the data for matched subjects. Heat maps and dendrograms were created to visualize the relationship of the PCR results between miRNAs. “t” test was used to differentiate between control and patient groups like gender, ejection fraction etc., otherwise Wilcoxon test was used like for age comparison. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze the group differences and Wilcoxon rank was used to compare miRNA expression for other factors. The statistical analysis was performed using JMP 5.1, SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, USA). Furthermore, Welch t-test was performed on the miRNA microarray data to assess for changes in miRNA expression. Changes in miRNAs were validated on an independent cohort of patient samples use real-time qPCR reactions represented as fold over internal control for each sample. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was carried out for miRNA-548c and BNP, and addition of miRNA-548c to BNP on data sets for the DCM patients and the non failing controls. ROC analysis was used to assess sensitivity, specificity and alpha parameter was optimized to maximize the area under the curve (to assess correlation between expression of miRNA-548c and BNP with cardiac dysfunction manifesting in DCM.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

To test the idea that circulating PBMCs in chronic heart failure patients may have a unique miRNA signature, PBMCs were isolated from non-failing controls and patients diagnosed with DCM. Patients were classified into NYHA class II/III (ejection fraction of ≤ 40%) or ‘stage C’ according to the ACC/AHA guidelines [34]. The ejection fraction in the DCM patients was ~26% compared to controls with ejection fraction ~60%. Control subjects included prospectively recruited, apparently healthy subjects with no evidence of cardiomyopathy as confirmed by echocardiography on enrollment. Echocardiography was a critical element of our study as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF < 40 %) was used as a primary cut-off for classifying controls. Thus, subject volunteers (non-failing controls) in the study had co-morbid conditions like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia. Consistent with cardiac dysfunction, DCM patients had significantly higher levels of BNP ~ 86.9 (29.3-345.4) pg/mL compared to non-failing controls ~ 19.0 (5.0-30.8) pg/mL. The patients based on their clinical diagnosis were on combination of medications like beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, aldosterone inhibitors or statins (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of DCM patients and non-failing controls.

Characteristics of patients used in the study. The data presented for age and LVEF % are mean ± standard deviation while all the other data point are “n” i.e., number of patients.

| Characteristics | Controls (48) | DCM (44) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.2 ± 9.0 | 51.9 ± 8.6 |

| Male | 25 | 24 |

| Female | 23 | 20 |

| LVEF (%) | 60 ± 3.9 | 26 ± 11.0* |

| Hypertension | 6 | 26 |

| Diabetes | 5 | 10 |

| Dyslipidemia | 4 | 18* |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 0 | 8* |

| ACEi/ARB | 4 | 23* |

| Beta-blocker | 2 | 31* |

| Aldosterone Inhibitor | 1 | 13* |

| Statins | 2 | 18* |

p<0.05

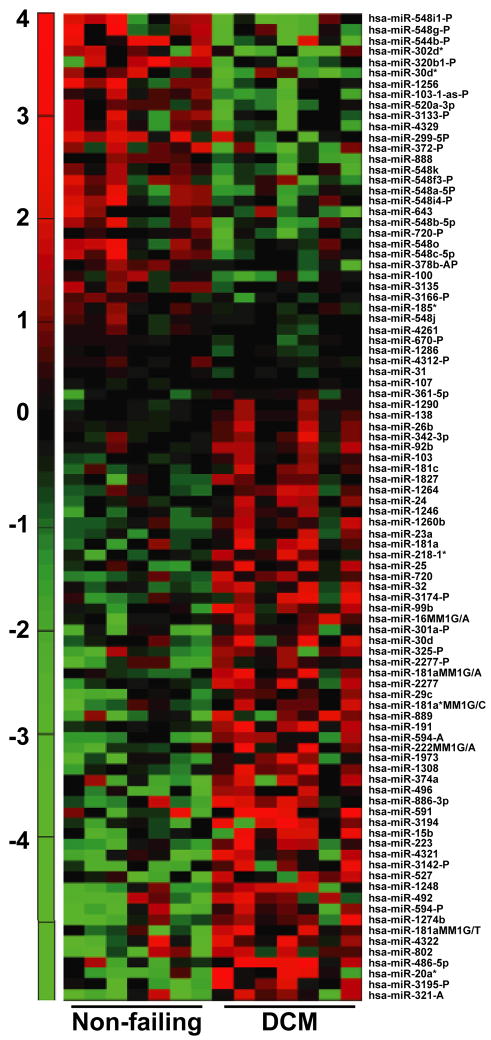

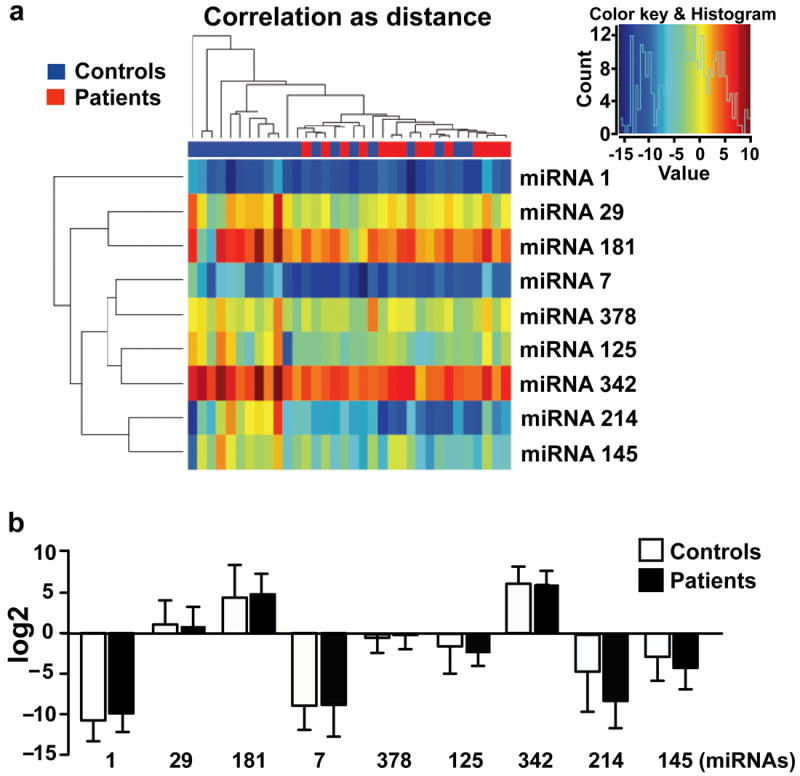

miRNA signature in the heart during end-stage DCM is not mirrored in PBMCs from DCM patients

Increasing evidence shows that circulating PBMCs have altered gene expression profiles in response to a pathology [35]. In some instances, studies have reported mirroring effect on expression of certain proteins in PBMCs compared to pathological tissue [36]. To test whether changes in the miRNA expression of PBMCs from DCM patients mimics our previous cardiac miRNA pattern in the end-stage heart failure [11], eight miRNAs representing the cardiac miRNA signature were assessed in PBMCs isolated from DCM patients by real time PCR. Surprisingly, we observed that none of the miRNAs significantly mirror the cardiac miRNA expression pattern which is further supported by clustering analysis (Fig. 1 a & b). Thus, our comprehensive analysis showed that altered cardiac miRNAs did not mirror miRNA expression profile of the DCM PBMCs. This suggests that miRNA profile in PBMCs may be different and a unique miRNA signature in PBMCs could be an independent predictor of ongoing cardiac dysfunction.

Figure 1. Quantitative Real Time PCR Analysis.

(a) Dendrogram analysis based on real time PCR for 8 miRNAs (miRNA-1, -7, -29, -145, -378, -342, -125, -181) in PBMCs from 48 controls and 44 DCM patients. Expression pattern of 8 miRNAs is shown as a heat map. (b) Log 2 transformation of real time PCR data on 8 miRNAs from PBMCs shows no significant differences between control and DCM patients (data presented as mean ± standard deviation).

Changes in expression of miRNA-548 family is a signature for DCM in PBMCs

Since miRNAs from PBMCs do not mirror the cardiac miRNA signature, we carried out genome-wide miRNA microarray to determine whether PBMCs from DCM patients have a specific miRNA signature. RNA was isolated from PBMCs of non-failing controls and DCM patients, and subjected to hybridization using custom-designed microarray chip containing 3060 miRNA probes of 948 human miRNA genes for performing the miRNA microarray. The microarray chip has two internal controls that were used for analyzing the data from controls and patient samples. Based on these analyses, our microarray data showed that ~ 9% of miRNAs were altered in PBMCs from DCM patients compared to their controls (Table 2). Expression profile of altered miRNAs in PBMCs following genome wide miRNA microarray showed a distinctive differences between control and DCM patient samples (Fig.2). Our analysis showed that 43% of the miRNAs detected on the chip indicated that PBMCs express a large repertoire of miRNAs. Assessment of changes in expression patterns were normalized to two internal controls on the chip, which was then used for determining differential expression of the miRNAs between controls and DCM samples. Consistent with our observation in the mirroring studies, none of the miRNAs belonging to the cardiac miRNA signature were significantly altered in the genome-wide microarray. Indepth examination of the microarray data revealed a unique observation that all members of the miRNA-548 family were significantly downregulated in DCM samples compared to non-failing controls and accounted for 30% of the total downregulated miRNAs in the PBMCs from DCM patients (Table 2 and 3).

Table 2. Dysregulated human microRNAs (with 0.05 as the p-value cutoff for significance).

Complete list of up- and down-regulated miRNAs from the microarray analysis in the PBMCs from the IDCM patients with a cut off p value <0.05.

| Name | p-value | Regulation (patient/control) | FCAbsolute |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-mir-103-1-as-P | 0.001351766 | down | 3.6472478 |

| hsa-miR-888 | 0.001794384 | down | 2.9298382 |

| hsa-miR-548i1-P | 0.008119636 | down | 7.5614033 |

| hsa-miR-548k | 0.012999459 | down | 2.8731618 |

| hsa-miR-520a-3p | 0.01381814 | down | 3.639056 |

| hsa-miR-320b1-P | 0.014457719 | down | 4.297423 |

| hsa-miR-4329 | 0.016708361 | down | 3.462207 |

| hsa-miR-544b-P | 0.018964175 | down | 5.820634 |

| hsa-miR-548c-5p | 0.021363791 | down | 2.4737914 |

| hsa-miR-185* | 0.024127489 | down | 1.533757 |

| hsa-miR-1256 | 0.025691833 | down | 3.9424562 |

| hsa-miR-720-P | 0.02636718 | down | 2.575244 |

| hsa-miR-548g-P | 0.026922343 | down | 6.1039033 |

| hsa-miR-378b-AP | 0.027374316 | down | 2.1323838 |

| hsa-miR-670-P | 0.029510088 | down | 1.3580612 |

| hsa-miR-548j | 0.030400496 | down | 1.4803556 |

| hsa-miR-1286 | 0.030918092 | down | 1.3274571 |

| hsa-miR-548b-5p | 0.032356746 | down | 2.580495 |

| hsa-miR-548i4-P | 0.03333728 | down | 2.6112447 |

| hsa-miR-30d* | 0.035266604 | down | 4.245023 |

| hsa-mir-548f3-P | 0.036472537 | down | 2.6808953 |

| hsa-mir-31 | 0.037211094 | down | 1.2628751 |

| hsa-miR-302d* | 0.03802914 | down | 5.02488 |

| hsa-miR-299-5p | 0.038446095 | down | 3.4513738 |

| hsa-miR-3135 | 0.040039454 | down | 1.7061 |

| hsa-miR-100 | 0.040666003 | down | 2.070374 |

| hsa-miR-3166-P | 0.041001417 | down | 1.6084788 |

| hsa-miR-548a-5p | 0.041009057 | down | 2.624389 |

| hsa-miR-4261 | 0.04198919 | down | 1.4045098 |

| hsa-miR-548o | 0.043245018 | down | 2.5343826 |

| hsa-miR-3133-P | 0.043495655 | down | 3.4868066 |

| hsa-miR-4312-P | 0.043669175 | down | 1.3193562 |

| hsa-mir-372-P | 0.04670943 | down | 3.38201 |

| hsa-miR-643 | 0.047467746 | down | 2.6057115 |

| hsa-miR-1308 | 0.001769467 | up | 3.4210255 |

| hsa-miR-138 | 0.002168255 | up | 1.2143077 |

| hsa-mir-594-A | 0.004509613 | up | 3.1950817 |

| hsa-miR-720 | 0.005277302 | up | 2.4933453 |

| hsa-miR-486-5p | 0.005523071 | up | 5.3048115 |

| hsa-miR-223 | 0.005915368 | up | 3.9657464 |

| hsa-miR-107 | 0.005982313 | up | 1.690859 |

| hsa-miR-191 | 0.007222734 | up | 3.1832972 |

| hsa-miR-3195-P | 0.007773686 | up | 5.7679286 |

| hsa-miR-103 | 0.007916251 | up | 1.8157521 |

| hsa-miR-496 | 0.008966818 | up | 3.5398676 |

Figure 2. Genome wide miRNA-microarray.

Heat map showing the expression of miRNAs from PBMCs altered in controls (n=7) and DCM patient samples (n=7). Analysis of the heat map shows a clear difference in the expression of miRNA profile in PBMCs from DCM patients and non-failing controls.

Table 3. miRNA-548 family members in PBMCs from DCM patient samples.

miRNA-548 family members significantly downregulated in microarray analysis.

| IPA_Name | Name | Value | Regulation | FCAbsolute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-548a | hsa-miR-548a-5p | 0.041009 | down | -2.62439 |

| hsa-miR-548b | hsa-miR-548b-5p | 0.032357 | down | -2.5805 |

| hsa-miR-548c | hsa-miR-548c-5p | 0.021364 | down | -2.47379 |

| hsa-miR-548f | hsa-miR-548f3-P | 0.036473 | down | -2.6809 |

| hsa-miR-548g | hsa-miR-548g-P | 0.026922 | down | -6.1039 |

| hsa-miR-548i | hsa-miR-548i1-P | 0.00812 | down | -7.5614 |

| hsa-miR-548i | hsa-miR-548i4-P | 0.033337 | down | -2.61124 |

| hsa-miR-548j | hsa-miR-548j | 0.0304 | down | -1.48036 |

| hsa-miR-548k | hsa-miR-548k | 0.012999 | down | -2.87316 |

| hsa-miR-548o | hsa-miR-548o | 0.043245 | down | -2.53438 |

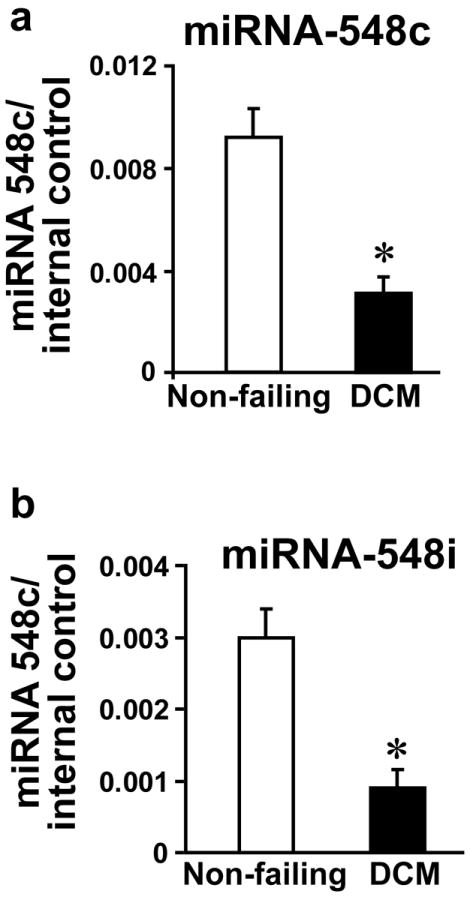

As miRNA-548 family members were downregulated in the genome-wide miRNA-microarray, we sought to validate whether miRNA-548 could be a specific signature in PBMCs from DCM patients. We used one of the least downregulated miRNA, miRNA-548c and one of the most downregulated miRNA, miRNA-548i (Table 3) as the representative members of miRNA-548 family. Real-time PCR was carried out in PBMCs from an independent set of non-failing controls (n=41) and DCM patient (n=37) samples. Real time PCR showed that miRNA-548c was significantly downregulated in PBMCs from DCM patients validating the microarray data (Fig. 3a). Similarly, miRNA-548i was also significantly downregulated in PBMCs from DCM patients as compared to the non failing controls (Fig. 3b) further validating the microarray results. In order to reaffirm our validation strategy, we also carried out real time PCR with an upregulated miRNA, miRNA-138 which shows up in the microRNA-microarray (Table 2). Consistent with the microarray data our real time PCR results showed that miRNA-138 was upregulated in PBMCs from DCM patients (Supplementary Fig. 1) suggesting fidelity in our experimental approach. Assessment of miRNA 548c in PBMCs from patients having coronary artery disease with absence of heart failure (left ventricular ejection fraction ~ 59.6%) showed no significant differences in expression compared to non-failing controls (Supplementary Fig. 2a) further supporting the DCM specificity of miRNA 548c. Together, our results showed that miRNA-548 gene expression was altered in PBMCs from patients who had been classified into NYHA class II/III suggesting that miRNA changes in PBMCs could be observed even at early heart failure stage.

Figure 3. Validation of miRNA-548 family members by real time PCR.

(a & b) RNA was isolated from the PBMCs from the control and DCM patients on an independent set of controls and patients with DCM. Reverse transcription was carried out to analyze the miRNA-548 members, miRNA-548c (41 Controls and 37 DCM) (data is presented as fold over internal control – RNU6). Similar analysis was carried out for miRNA-548i.

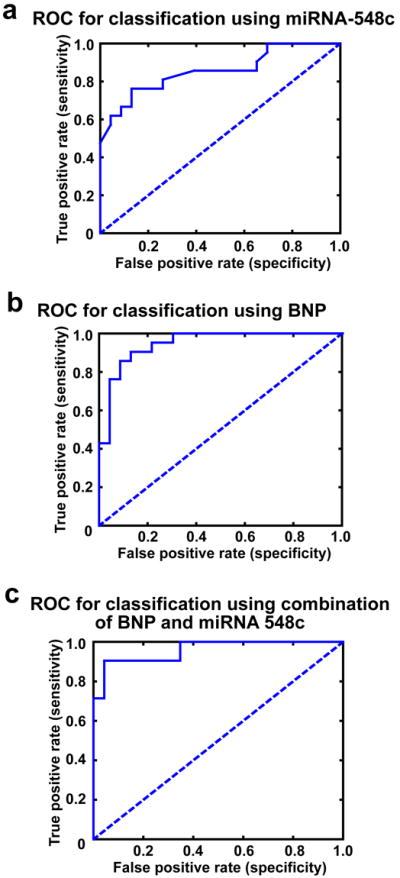

Our data showed significant reduction in expression of miRNA-548 family in PBMCs from patients having persistent cardiac dysfunction (LVEF< 40%). To test whether there is correlation between miRNA-548 signature in PBMCs to heart failure, we carried out ROC analysis using miRNA-548c as a representative member of the 548 family as it was one of the least downregulated member. ROC analysis on the data set from real time PCR showed miRNA-548c with significant area under the curve implying that it has the discriminatory power to distinguish DCM PBMCs from non-failing controls (Fig. 4a). To test whether our observation has a correlation with a conventional biomarker, we used BNP measurements from these patients for ROC analysis. ROC analysis for BNP showed significant area under the curve with a clear discrimination between the DCM and non-failing controls (Fig. 4b). In order to further evaluate the incremental discriminatory power of miRNA-548c, we assessed the change in area under the curve following linear combination of miRNA-548c with BNP. Importantly, paired combination increases the area under the curve showing clear discriminatory power of miRNA-548c (Fig. 4c). An overlay of the ROC analysis is shown in the supplementary data to show the ability of miRNA-548c to distinguish DCM samples from non-failing controls (Supplementary Fig. 3). Our data suggests that miRNA-548c has the power to distinguish DCM from non-failing controls analogous to the well established BNP in the PBMCs. This study hence, lays the foundation that miRNA-548 signature may serve as a powerful tool to predict cardiac dysfunction as it evolves as a potential biomarker.

Figure 4. ROC analysis.

(a) Receiver Operating characteristic (ROC) curve for miRNA-548c shows area under the curve to be 85.51% with a significance value of p<0.0001 given that the data generated is from miRNA expression from PBMC. (b) ROC curve for BNP from the plasma, area under the curve is 94.62% with a significance value of p<0.0001. BNP values were measured by ELISA from non failing controls and DCM patients which were used for ROC analysis. (c) ROC curve for the simple linear combination of miRNA-548c with BNP showed increased strength of sensitivity as measured by the area under the curve (95.86%) with a significance value of p<0.0001.

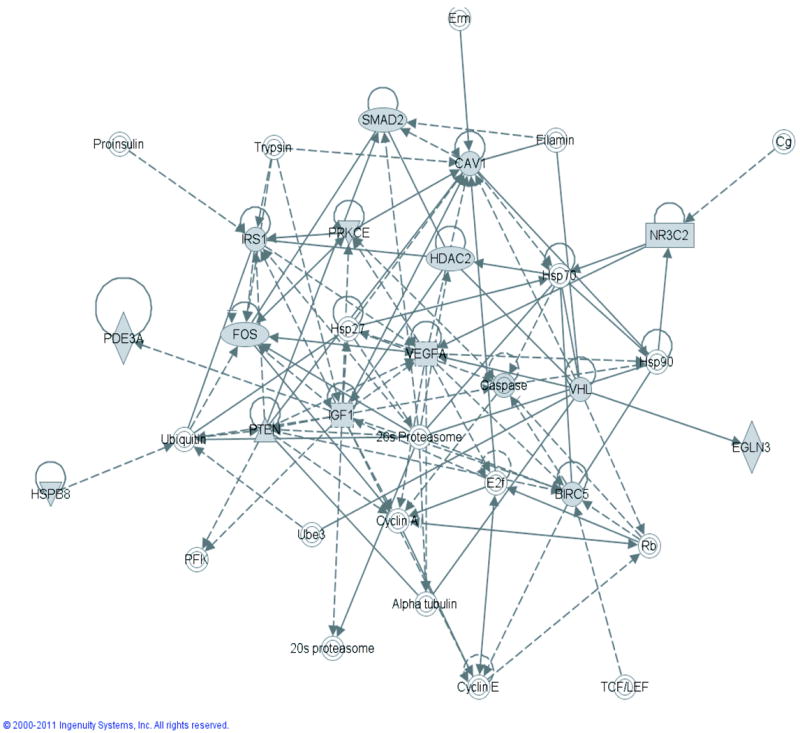

Network analysis of miRNA-548

ROC analysis of the miRNA-548c suggests that miRNA signature in PBMCs may have the potential to predict cardiac dysfunction. Therefore, using in silico networking analysis we assessed whether predicted targets of miRNA-548 signature could provide insights into analogous changes in enriched signaling pathways of PBMCs in response to ongoing pathology (heart failure). Network analysis on predicted targets of miRNA-548 was carried out using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). IPA provides an independent method of assessing the role of predicted miRNA-548 targets. In this regard, use of miRNA-548 targets in the networking analysis showed that the maximum number of 548 targets that could be engaged in functional network were cardiovascular signaling and disease (Table 4a). Thus, by this unbiased virtue of queried knowledge base, cardiovascular signaling and disease were the top networks as this analysis utilizes the maximum number of targets to generate a functional signaling network [37]. Associated with the network are the focus molecules which determine the signaling outcome and the top network has 15 nodal molecules that are predicted targets of miRNA-548 like VEGF, IGF, IRS, HDAC2, etc. (Fig. 5). Similarly, the second network has 14 miRNA-548 target molecules including members of PDE and AKAP family members as nodal molecules (Supplementary Fig. 4). The unbiased network analysis provides an idea on the potential functional changes that could occur in DCM PBMCs due to changes in altered miRNAs. Since each of the molecules in the network contributes to the overall signaling pathway and the functional outcome, identification of networks regulated by specific miRNAs in PBMCs can provide us with readouts that may potentially have relevance to specific pathologies. In this context, IPA functional algorithm shows that miRNA-548c which is altered in DCM PBMCs has targets that are notably enriched in cardiovascular system development (Table 4a) (top network). This is further supported by cardiovascular disease as the next top network (Table 4a) suggesting that such analysis in PBMCs may provide an analogous readout which could be used as ancillary tool to recognize an ongoing pathology.

Table 4.

Functional Network analysis: IPA analysis on targets of miRNA-548 shows that one of the top associated network function to be cardiovascular system development function (a), top disease and disorder function as cardiovascular disease (b) and cardiac hypertrophy as the top toxicity function (c).

|

a

Top Tox lists

| ||

|---|---|---|

| ID | Associated Network Functions | Score |

| 1 | Cardiovascular System Development and function Dermatological Diseases and Conditions, Tissue Morphology. | 25 |

| 2 | Cardiovascular Disease, Cell Death, Gastro-intestinal Disease. | 23 |

| 3 | Inflammatory Response, Cellular Movement, Hematological Development and Function. | 20 |

| 4 | Cellular Development, Cellular Growth and Proliferation, Connective Tissue Development And Function. | 19 |

| 5 | Cardiovascular System Development and Function, Amino Acid Metabolism, Molecular Transport. | 17 |

|

| ||

|

b

Diseases and Disorders

| ||

| Name | p-value | # Molecules |

|

| ||

| Cardiovascular Disease | 5.76E-76-2.06E-13 | 137 |

| Development Disorder | 1.81E-71-9.56E-14 | 80 |

| Hematological Disease | 9.53E-59-1.57E-13 | 107 |

| Skeletal and Muscular Disorders | 2.54E-40-9.56E-14 | 103 |

| Inflammatory Disease | 1.14E-39-2.68E13 | 107 |

|

| ||

|

c

Top Tox lists

| ||

| Name | p-value | Ratio |

|

| ||

| Cardiac hypertrophy | 3.28E-60 | 53/259 (0.205) |

| Liver Proliferation | 1.3E-22 | 22/133 (0.165) |

| Cardiac Fibrosis | 2.61E-21 | 19/95 (0.2) |

| Cardiac Necrosis/Cell Death | 1.11E-19 | 21/156 (0.135) |

| Renal Necrosis/Cell Death | 1.43E-16 | 34/314 (0.076) |

Figure 5. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) on predicated targets of miRNA-548.

Top network associated with 15 predicated targets of miRNA-548 is shown. Many of the molecules represented in the network are critical molecules in stress signaling indicating that the predicted targets may show a reflection of ongoing pathology in specific tissues.

In addition, IPA algorithm provides the means to assess the disease and disorder prediction using the representative networks containing 145 miRNA-548 targets. In this regard, the IPA algorithm utilizes the queried knowledge base in various diseases and overlays the miRNA-targets to the already mapped network of molecules enriched in specific diseases. We used the predicted targets of miRNA-548 to assess the disease and disorder prediction using IPA algorithm. Interestingly, independent in silico analysis predicted cardiovascular disease (Table 4b) to be strongly associated with miRNA-548 targets. Other disease and disorder functions associated with miRNA-548 targets were developmental, hematological and muscular disorders (Table 4b). Since, the top disease disorder function associated with miRNA-548 targets was cardiovascular disease, we used IPA-toxicity algorithm to assess the enrichment of the targets in specific toxicity pathways built on the queried knowledge of signaling pathways altered in pathology [37]. IPA-toxicity analysis utilizing networks containing miRNA-548 targets showed cardiac hypertrophy/cardiac fibrosis as one of the top Tox functions for miRNA-548 targets (Table 4c).

In light of the surprising observation that cardiovascular disease and cardiac fibrosis appear as top disease and toxicity function following use of miRNAs from PBMCs of DCM patients, we tested whether such a correlation could exist between top altered miRNAs in PBMCs to an alternate pathology. Towards this goal, we carried out networking analysis on the top altered miRNAs from the genome-wide PBMC miRNA microarray on lupus nephritis patients identified by J.O. Ojwang’s group [38]. Importantly, the miRNA signature in the PBMCs from nephritis patients was different than the miRNA signature we observed in PBMCs from DCM patients. Despite the fact that our microarray had probes for miRNAs altered in nephritis PBMCs, none of these miRNAs were significantly altered in the DCM PBMCs suggesting that miRNA expression in PBMCs may vary based on the specific disease. Functional networking analysis of the top altered miRNAs in PBMCs from patients with nephritis showed the top network to be renal inflammation which is characterized by engagement of maximum number of miRNA targets from the top altered miRNAs (Supplementary Table 1a). Similarly, assessment of the miRNA targets from nephritis PBMCs with IPA algorithm for disease and disorders showed renal and urological disease as one of the top disease for this miRNA signature (Supplementary Table 1c). Further, renal nephritis and inflammation showed up as one of the top toxicity function following the use of top altered miRNAs in PBMCs from nephritis patients (Supplementary Table 1c). These data together with our miRNA signature in PBMCs from DCM shows that changes in PBMCs can potentially reflect ongoing pathology laying the idea that miRNA signature may be reliable predictor of a disease. In this context, representation of IPA functional analysis in PBMCs maybe a reflection of altered miRNAs in response to stress supporting the idea that circulating PBMCs can potentially be active sensors of the ongoing pathological stress.

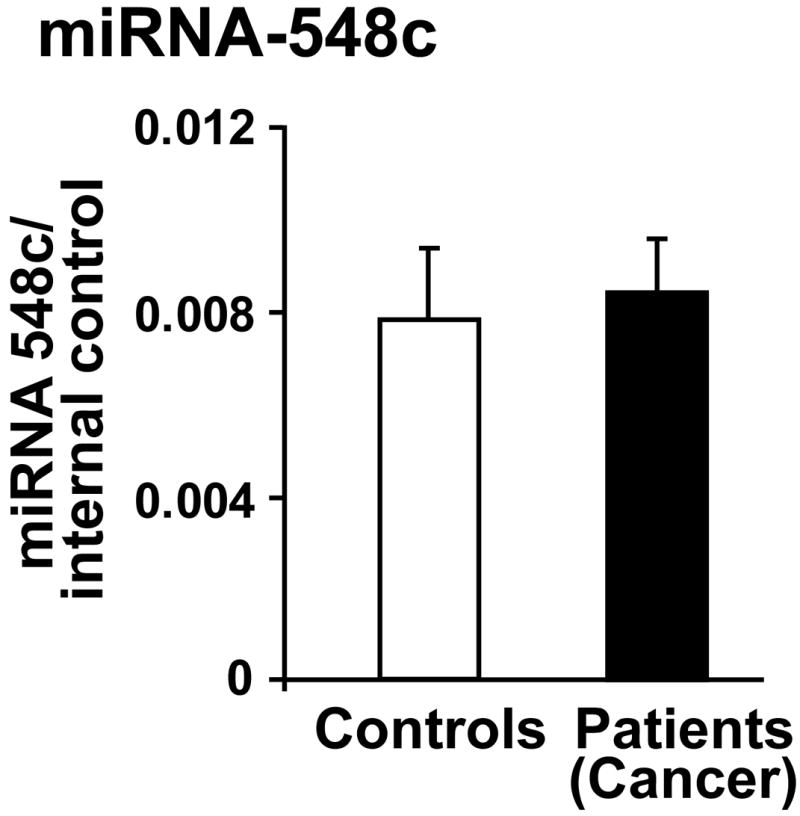

miRNA-548 is unaltered in PBMCs from breast cancer patients

Our studies suggest that PBMCs can sense an ongoing pathology and respond by altering specific miRNAs. To test whether miRNA-548 alteration is specific to DCM, we assessed miRNA-548c in PBMCs from metastatic breast cancer patients (patients characteristics is presented in Table 5). Importantly, these patients were diagnosed with cancer for the first time and have no indications of cardiac disease. More importantly these patients were on no medications prior to blood draw and specific treatment was initiated post blood draw following identification of metastatic breast cancer is shown in Supplementary Table 2. We carried out real time PCR analysis for miRNA-548c in PBMCs from these cancer patients and control subjects. Interestingly, real time PCR shows that miRNA-548c was not altered in PBMCs from cancer patients (Fig. 6) in contrast to the downregulation of miRNA-548c in DCM PBMCs (Fig. 2 and 3a). Since our study introduces gender bias, we analyzed miRNA-548c levels and found no differences in expression between non-failings male control cohort and female control patients of the breast cancer cohort (Supplementary Fig.2b). Therefore, these findings show that miRNA-548c alterations are gender independent and DCM selective. Together, our study suggests that PBMCs can potentially sense differential pathological stress and in turn respond by inducing specific miRNA expression that could be used as a readout for a given pathology.

Figure 6. Evaluation of miRNA-548 in PBMCs from metastatic cancer patients.

RNA was isolated from the PBMCs of metastatic cancer patients and controls. The RNA was subjected to real time PCR analysis for miRNA-548c (data is presented as fold over internal control). No appreciable difference in expression pattern of miRNA-548c was observed between PBMCs from controls and cancer patients.

DISCUSSION

We present evidence that miRNA signature in PBMCs from DCM patients is unique, laying the foundation to the idea that miRNAs pattern in PBMCs can potentially be used as surrogate readout for heart failure. We show that PBMCs from DCM patients have a unique signature which is characterized by significant downregulation of miRNA-548 family members. Network analysis on the predicted targets of miRNA-548c surprisingly revealed cardiovascular disease as a top altered function suggesting that the gene expression pattern in the PBMCs may reflect an ongoing pathology. To test the validity and consistency of this analysis in a different pathology, we carried out network analysis on the top altered miRNAs identified previously [38] in PBMCs from lupus nephritis patients and showed renal inflammation as a top function. Finally, assessment of miRNA-548c in PBMCs from breast cancer patients or patients with coronary artery disease showed no appreciable changes in miRNA-548 family expression suggesting selective alteration of miRNA-548 in PBMCs from DCM patients. These studies indicate that miRNA signatures in PBMC could be unique for a given pathology and can potentially be used as a predictor or surrogate readout.

Biomarkers in the circulation play a key role in risk stratification and therapeutic management of cardiac diseases [4, 22, 27, 39-41] as it is difficult to obtain anatomical tissue biopsies. Despite significant progress, lot remains desired with the current markers especially in terms of early detection of cardiac dysfunction. In this context, our current study highlights the potential to use miRNA signature in PBMCs as a predictor or biomarker in heart failure. miRNAs can serve as attractive biomarker in circulation due to their stability and protection from RNase-dependent degradation [42-44]. Consistently, recent studies have shown plasma miRNAs as useful biomarkers for diagnosis of multiple cancers [44, 45] and the unique strength of miRNAs during early detection of the pathology. Similarly, multiple studies have also investigated the potential use of miRNAs in plasma or serum as biomarkers for cardiovascular disease [4, 27]. A critical issue with plasma or serum biomarker that needs to be resolved is the tissue of its origin. In case of heart failure, whether these miRNAs are released from the cardiac tissue following injury or from other tissues as a secondary effect to the cardiac stress needs to be resolved in order to use plasma miRNAs as potential readouts. Furthermore, serum or plasma biomarker though valuable may not represent an actively changing molecular phenotype during early cardiac pathology. Therefore, we have used circulating PBMCs with the premise that PBMCs would be able to sense ongoing cardiac dysfunction and respond by altering their transcriptome including miRNA expression [35, 36]. In addition to identifying previously shown miRNAs in PBMCs from end-stage heart failure patients [27], we have identified novel miRNA signature, miRNA-548 family by utilizing comprehensive miRNA microarray. In this context, we believe that it is still possible to identify new miRNAs as only 49% of the 1900 known human miRNAs [57] are being used as probes. Critically, miRNA-548 family is downregulated in PBMCs from heart failure patients and was not altered in PBMCs from metastatic cancer patients suggesting that miRNA-548 expression can be used as a potential PBMC signature specific for cardiac dysfunction. Furthermore, our studies showed that miRNAs altered in PBMCs from heart failure patients does not mirror or overlap with cardiac miRNA signature suggesting that PBMCs may have their unique miRNA signature in response to cardiac dysfunction.

Identification of miRNA-548 signature in PBMCs from patients with cardiac dysfunction is a novel finding of our study. A surprising observation of our genome-wide microarray was consistent downregulation of miRNA-548 family members which represented ~30% of the downregulated miRNAs in DCM PBMCs. Our analysis showed that miRNA-548 family members (Table 3) are downregulated in DCM PBMCs strengthening the idea that miRNA-548 has the potential to be a selective biomarker for cardiac dysfunction. Importantly, ROC analysis on the representative miRNA-548c showed that miRNA-548c had the discriminatory power to differentiate between non-failing and DCM patient samples nearly similar to the classical BNP as assessed by the ROC analysis. Thus, these studies provide the “proof of concept” to the idea that miRNA signatures in PBMCs can potentially developed to be a biomarker for heart failure in future. Consistent with this postulation, we did not observe significant changes in miRNAs reported to be part of miRNA signature in PBMCs from lupus nephritis patients [38]. Integral to evolution of miRNAs a potential biomarker is the increasing evidence that miRNAs critically regulate various biological processes including inflammation [46-48].

miRNA-548 is a recently discovered human miRNA gene family that is derived from the miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) and is represented by multiple members [48]. Corresponding to their origin from MITEs, miRNA-548 genes are primate specific with paralogs in the human genome that has been used in our microarrays. Bioinformatic analysis of predicted miRNA-548 targets suggest their role in inflammation [49]. Consistently, recent study has shown that miRNA-548 regulates host anti-viral response by targeting IFN-λ1 [50]. Surprisingly, miRNA-548 members are not poly-cistronic transcripts but are encoded from independent set of genes like miRNA-548i which is encoded by its own gene while miRNA-548c is encoded from RASSF3 (Ras association RALGDS/AF-6) gene. Despite these miRNAs being encoded from different loci, their reproducible downregulation in PBMCs from DCM can be harnessed for reflecting cardiac pathology.

Although we do understand that the PBMCs and cardiac tissues have diverse functions, >80% of the PBMC transcriptome overlaps with cardiac transcriptome [35, 36]. Thus, networking algorithm can engage signaling molecules differentially expressed in response to miRNA alterations in pathology to assess whether they may enrich specific pathways [11, 37]. Network analysis on the predicted targets of miRNA-548 showed enrichment of pathways depicting cardiac pathophysiology. Such assessment could provide enhanced confidence on the potential use of PBMC miRNA signature as a potential predictor for a specific pathology. Consistently, network analysis of the predicted targets for top altered miRNAs in PBMCs from lupus nephritis (which has different miRNA signature) shows renal inflammation as top function. Our study indicates that miRNA profiles observed in PBMCs from different pathologies may vary and network analysis from these profiles could reflect specific disease. We believe the strength of our study not only lies in identifying a novel PBMC miRNA signature in heart failure but to meaningfully harness this data with parallel and careful utilization of bioinformatic tools. The idea that the miRNA signature in PBMCs could reflect the disease state in two independent studies (DCM- current study and lupus nephritis by Ojwang group) provides critical evidence to invest in comprehensive studies to develop miRNA signature in PBMCs as a biomarker. These observations support the idea that miRNA alterations occur as a consequence of a pathological event in which PBMCs may respond with a miRNA unique signature that may be selective for a given pathology. Such a concept is supported not only by our miRNA studies in breast cancer patients and patients with coronary artery disease with no heart failure but also from an independent study on PBMC isolated from lupus patients [38].

Our studies suggest that PBMCs can sense pathological molecular alterations like cardiac dysfunction due to potential changes in the inflammatory cytokines which are initiated upon any disease conditions and respond by altering their transcriptome including miRNA expression pattern. We believe that our study is a step forward to tap the potential of this unique communication between circulating PBMCs and dysfunctional heart. In this context, it is known that PBMC transcriptome is dynamic and can represent the ongoing changes specifically related to pathology [36]. As miRNAs are integral to the transcriptome, these changes will be reproducible with high fidelity and will vary with the ongoing disease suggesting that PBMC miRNA signature could potentially be used as a sentinel. This is supported by the evidence that miRNA expression profiles in PBMCs from various diseases are remarkably different [51-53], [54-56] providing a unique resource that can be capitalized for developing biomarkers for pathology. Importantly, our data indicates the presence of an active dialogue between the circulating PBMCs and the diseased tissue manifesting in altered PBMC miRNA profile. Though the concept of cross-talk is very interesting, understanding of this process is important but is out of the scope of current work. Despite the complexities in our study, we observe significant downregulation of miRNA-548 in PBMCs from DCM patients supporting the concept that PBMC miRNA signature may vary in response to specific pathology and could serve as readout for chronic disease.

Limitations of the study

Our study has limitations just like any other human subject study. This study was not powered to determine differences across different NHYA class or degree of LV impairment but is the first study to determine whether miRNA profile is altered in PBMCs with DCM (so-called “Stage C heart failure” with signs and symptoms already manifested at the time of diagnosis) using the most comprehensive miRNA microarray. These studies are also limited by the availability of PBMCs from patients with earlier stages of (e.g. Stage B) heart failure. Nevertheless, these results lay a foundation for a future study involving comprehensive enrollment and assessment of patients at various stages of heart failure. We acknowledge that there are discrepancies in baseline characteristics and medication used between the DCM and control groups, which are inherent in a cross-sectional study. As our study is one of the first to look across other pathologies for changes in miRNA signatures in PBMCs, we have come to appreciate the complexities of changes in gene expression patterns. Therefore, our studies can be considered as “proof-of-concept” pilot study for using miRNA signatures as potential biomarkers for specific pathology. In this regard, further work is needed to rigorously assess the mechanisms underlying the cross-talk between PBMCs and pathological organ to develop PBMC miRNA signature as a future diagnostic tool.

Supplementary Material

miRNA-138 was validated by real time PCR on an independent set of DCM patient samples (data is presented as fold over internal control).

(a) RNA was isolated from the PBMCs from an independent set of non-failing controls (n=10) and patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) (n=9) but with no heart failure as measured by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ~ 59.6). Reverse transcription was carried out to analyze the miRNA-548c and the data is presented as fold over internal control. CAD patients characteristics (n=9); Gender: Males 5, Females 4; LVEF ~ 59.63; Aspirin: n=9; Statin: n=8; ACE inhibitor: n=4; Beta-blocker: n=5. (b) RNA was isolated from the PBMCs isolated from male non-failing controls and females control samples from the breast cancer cohort. Reverse transcription was carried out to analyze miRNA-548c and the data is presented as fold over internal control.

Overlay of the ROC curves for the miRNA-548c (blue), BNP (red), and linear combination of miRNA-548c with BNP (green) shows incremental discriminatory power of PBMC miRNA-548c.

Second network of miRNA-548 targets.

Network analysis of targets of altered miRNAs in PBMCs from lupus nephritis.

Table showing characteristics of metastatic breast cancer patients.

Highlights.

miRNA-548 family is a unique miRNA signature in PBMCs from DCM patients.

miRNA-548 family members are significantly downregulated in the DCM PBMCs.

miRNA-548c can be used as a representative member of miRNA-548 family.

miRNA-548c was unaltered in PBMCs from breast cancer or CAD patients.

Canonical network analysis can be used as a powerful ancillary tool to predict pathology.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Sadashiva Karnik and Edward Plow, Department of Molecular Cardiology, Cleveland Clinic for their constant support and insightful thoughts.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from NIH (SVNP), NIH R01HL103931 (WHWT), and AHA 10POST3610049 (MKG)

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.K.G., C.H., J.L., S.J., X.L., M.L.M., N.T.V. and K.A. performed experiments; M.K.G., Z.D., J.N., K.S., W.H. W.T. and S.V.NP analyzed data; M.K.G., K.S. and S.V.N.P. interpreted results of experiments; M.K.G., Z.D., J.N. and S.V.NP prepared figures; M.K.G., C.H., M.L.M., N.T.V., W.H.W.T. and S.V.N.P. edited and revised manuscript; C.L., W.H.W.T. and S.V.N.P. approved final version of manuscript; M.K.G., S.V.N.P. and W.H.W.T. conception and design of research; M.K.G., W.H.W.T. and S.V.N.P. drafted manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.van Rooij E, Liu N, Olson EN. MicroRNAs flex their muscles. Trends Genet. 2008;24:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammond SM. Dicing and slicing: the core machinery of the RNA interference pathway. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5822–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP, Chen CZ. Micromanagers of gene expression: the potentially widespread influence of metazoan microRNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:396–400. doi: 10.1038/nrg1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorn GW., 2nd Therapeutic potential of microRNAs in heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 12:209–15. doi: 10.1007/s11886-010-0096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matkovich SJ, Van Booven DJ, Youker KA, Torre-Amione G, Diwan A, Eschenbacher WH, et al. Reciprocal regulation of myocardial microRNAs and messenger RNA in human cardiomyopathy and reversal of the microRNA signature by biomechanical support. Circulation. 2009;119:1263–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorn GW., 2nd MicroRNAs in cardiac disease. Transl Res. 157:226–35. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small EM, Olson EN. Pervasive roles of microRNAs in cardiovascular biology. Nature. 469:336–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topkara VK, Mann DL. Role of microRNAs in cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 25:171–82. doi: 10.1007/s10557-011-6289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayed D, Hong C, Chen IY, Lypowy J, Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs play an essential role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2007;100:416–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257913.42552.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thum T, Catalucci D, Bauersachs J. MicroRNAs: novel regulators in cardiac development and disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:562–70. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naga Prasad SV, Duan ZH, Gupta MK, Surampudi VS, Volinia S, Calin GA, et al. Unique microRNA profile in end-stage heart failure indicates alterations in specific cardiovascular signaling networks. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27487–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Ikeda S, Kong SW, Lu J, Bisping E, Zhang H, Allen PD, et al. Altered microRNA expression in human heart disease. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:367–73. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00144.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, Seike M, Kumamoto K, Yi M, et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartels CL, Tsongalis GJ. MicroRNAs: novel biomarkers for human cancer. Clin Chem. 2009;55:623–31. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukoyama M, Nakao K, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Hosoda K, Suga S, et al. Increased human brain natriuretic peptide in congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:757–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009133231114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello-Boerrigter LC, Burnett JC., Jr The prognostic value of N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2:194–201. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, 3rd, Criqui M, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emdin M, Vittorini S, Passino C, Clerico A. Old and new biomarkers of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:331–5. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lainscak M, von Haehling S, Anker SD. Natriuretic peptides and other biomarkers in chronic heart failure: from BNP, NT-proBNP, and MR-proANP to routine biochemical markers. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannitsis E, Katus HA. Troponins and high-sensitivity troponins as markers of necrosis in CAD and heart failure. Herz. 2009;34:600–6. doi: 10.1007/s00059-009-3306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rottbauer W, Greten T, Muller-Bardorff M, Remppis A, Zehelein J, Grunig E, et al. Troponin T: a diagnostic marker for myocardial infarction and minor cardiac cell damage. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(Suppl F):3–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/17.suppl_f.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manzano-Fernandez S, Boronat-Garcia M, Albaladejo-Oton MD, Pastor P, Garrido IP, Pastor-Perez FJ, et al. Complementary prognostic value of cystatin C, N-terminal proB-type natriuretic Peptide and cardiac troponin T in patients with acute heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1753–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creemers EE, Tijsen AJ, Pinto YM. Circulating microRNAs: novel biomarkers and extracellular communicators in cardiovascular disease? Circ Res. 2012;110:483–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adachi T, Nakanishi M, Otsuka Y, Nishimura K, Hirokawa G, Goto Y, et al. Plasma microRNA 499 as a biomarker of acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1183–5. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.144121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang GK, Zhu JQ, Zhang JT, Li Q, Li Y, He J, et al. Circulating microRNA: a novel potential biomarker for early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in humans. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:659–66. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoekstra M, van der Lans CA, Halvorsen B, Gullestad L, Kuiper J, Aukrust P, et al. The peripheral blood mononuclear cell microRNA signature of coronary artery disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 394:792–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tijsen AJ, Creemers EE, Moerland PD, de Windt LJ, van der Wal AC, Kok WE, et al. MiR423-5p as a circulating biomarker for heart failure. Circ Res. 106:1035–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rollins B, Martin MV, Morgan L, Vawter MP. Analysis of whole genome biomarker expression in blood and brain. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 153B:919–36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gow JW, Hagan S, Herzyk P, Cannon C, Behan PO, Chaudhuri A. A gene signature for post-infectious chronic fatigue syndrome. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:38. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belzeaux R, Formisano-Treziny C, Loundou A, Boyer L, Gabert J, Samuelian JC, et al. Clinical variations modulate patterns of gene expression and define blood biomarkers in major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 44:1205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang B, Lo C, Shen L, Sood R, Jones C, Cusmano-Ozog K, et al. The role of vanin-1 and oxidative stress-related pathways in distinguishing acute and chronic pediatric ITP. Blood. 117:4569–79. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-304931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu CG, Calin GA, Volinia S, Croce CM. MicroRNA expression profiling using microarrays. Nature protocols. 2008;3:563–78. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:e391–479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohr S, Liew CC. The peripheral-blood transcriptome: new insights into disease and risk assessment. Trends in molecular medicine. 2007;13:422–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liew CC, Ma J, Tang HC, Zheng R, Dempsey AA. The peripheral blood transcriptome dynamically reflects system wide biology: a potential diagnostic tool. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2006;147:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naga Prasad SV, Karnik SS. MicroRNAs--regulators of signaling networks in dilated cardiomyopathy. Journal of cardiovascular translational research. 2010;3:225–34. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9177-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Te JL, Dozmorov IM, Guthridge JM, Nguyen KL, Cavett JW, Kelly JA, et al. Identification of unique microRNA signature associated with lupus nephritis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lainscak M, Anker MS, von Haehling S, Anker SD. Biomarkers for chronic heart failure : diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic challenges. Herz. 2009;34:589–93. doi: 10.1007/s00059-009-3316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katus HA, Remppis A, Looser S, Hallermeier K, Scheffold T, Kubler W. Enzyme linked immuno assay of cardiac troponin T for the detection of acute myocardial infarction in patients. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989;21:1349–53. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Risk stratification and survival after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:331–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308113090602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung M, Schaefer A, Steiner I, Kempkensteffen C, Stephan C, Erbersdobler A, et al. Robust microRNA stability in degraded RNA preparations from human tissue and cell samples. Clin Chem. 56:998–1006. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.141580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilad S, Meiri E, Yogev Y, Benjamin S, Lebanony D, Yerushalmi N, et al. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10513–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ng EK, Chong WW, Jin H, Lam EK, Shin VY, Yu J, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer: a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2009;58:1375–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Botvinick EL, Zhao Y, Berns MW, Usami S, Tsien RY, et al. Visualizing the mechanical activation of Src. Nature. 2005;434:1040–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van de Vrie M, Heymans S, Schroen B. MicroRNA involvement in immune activation during heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 25:161–70. doi: 10.1007/s10557-011-6291-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prabhu SD. Cytokine-induced modulation of cardiac function. Circ Res. 2004;95:1140–53. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150734.79804.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piriyapongsa J, Jordan IK. A family of human microRNA genes from miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements. PLoS One. 2007;2:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Xie J, Xu X, Wang J, Ao F, Wan Y, et al. MicroRNA-548 down-regulates host antiviral response via direct targeting of IFN-lambda1. Protein & cell. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s13238-012-2081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otaegui D, Baranzini SE, Armananzas R, Calvo B, Munoz-Culla M, Khankhanian P, et al. Differential micro RNA expression in PBMC from multiple sclerosis patients. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meder B, Keller A, Vogel B, Haas J, Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Kayvanpour E, et al. MicroRNA signatures in total peripheral blood as novel biomarkers for acute myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 106:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ba Y, Cai X, Chen X, Yin Y, Zhang Y, Zhang CY. Down-regulative expression of microRNAs cluster in human colon tumorigenesis. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;88:1683–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Z, Huang D, Ni S, Peng Z, Sheng W, Du X. Plasma microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers for early detection of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 127:118–26. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heneghan HM, Miller N, Lowery AJ, Sweeney KJ, Newell J, Kerin MJ. Circulating microRNAs as novel minimally invasive biomarkers for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 251:499–505. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cc939f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang JF, Yu ML, Yu G, Bian JJ, Deng XM, Wan XJ, et al. Serum miR-146a and miR-223 as potential new biomarkers for sepsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 394:184–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

miRNA-138 was validated by real time PCR on an independent set of DCM patient samples (data is presented as fold over internal control).

(a) RNA was isolated from the PBMCs from an independent set of non-failing controls (n=10) and patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) (n=9) but with no heart failure as measured by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ~ 59.6). Reverse transcription was carried out to analyze the miRNA-548c and the data is presented as fold over internal control. CAD patients characteristics (n=9); Gender: Males 5, Females 4; LVEF ~ 59.63; Aspirin: n=9; Statin: n=8; ACE inhibitor: n=4; Beta-blocker: n=5. (b) RNA was isolated from the PBMCs isolated from male non-failing controls and females control samples from the breast cancer cohort. Reverse transcription was carried out to analyze miRNA-548c and the data is presented as fold over internal control.

Overlay of the ROC curves for the miRNA-548c (blue), BNP (red), and linear combination of miRNA-548c with BNP (green) shows incremental discriminatory power of PBMC miRNA-548c.

Second network of miRNA-548 targets.

Network analysis of targets of altered miRNAs in PBMCs from lupus nephritis.

Table showing characteristics of metastatic breast cancer patients.