Abstract

Background:

The physical demands required of the body to execute a shot in golf are enormous. Current evidence suggests that warm-up involving static stretching is detrimental to immediate performance in golf as opposed to active dynamic stretching. However the effect of resistance exercises during warm-up before golf on immediate performance is unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the effects of three different warm-up programs on immediate golf performance.

Methods:

Fifteen elite male golfers completed three different warm-up programs over three sessions on non-consecutive days. After each warm-up program each participant hit ten maximal drives with the ball flight and swing analyzed with Flightscope® to record maximum club head speed (MCHS), maximal driving distance (MDD), driving accuracy (DA), smash factor (SF) and consistent ball strike (CBS).

Results:

Repeated measures ANOVA tests showed statistically significant difference within 3 of the 5 factors of performance (MDD, CBS and SF). Subsequently, a paired t-test then showed statistically significant (p<0.05) improvements occurred in each of these three factors in the group performing a combined active dynamic and functional resistance (FR) warm-up as opposed to either the active dynamic (AD) warm-up or the combined AD with weights warm-up (WT). There were no statistically significant differences observed between the AD warm-up and the WT warm-up for any of the five performance factors and no statistical significant difference between any of the warm-ups for maximum clubhead speed (MCHS) and driving accuracy (DA).

Conclusion:

Performing a combined AD and FR warm up with Theraband® leads to significant increase in immediate performance of certain factors of the golf drive compared to performing an AD warm-up by itself or a combined AD with WT warm-up. No significant difference was observed between the three warm-up groups when looking at immediate effect on driving accuracy or maximum club head speed. The addition of functional resistance activities to active dynamic stretching has immediate benefits to elite male golfers in relation to some factors of their performance.

Level of Evidence:

This study is a Quantitative Experimental design using repeated measures and multiple crossovers. It cannot be classified using the descriptive level of evidence.

Keywords: Active dynamic, functional resistance, immediate performance, golf, warm-up

INTRODUCTION

Golf is an extremely popular sport played across the world regardless of gender, skill level or age. The physical demands required of the body to execute one of the most complex athletic skills are enormous.1,2 The golf swing is a highly coordinated, multi-segmental, rotational, closed chain activity, requiring strength, explosive power, flexibility and balance.3 Elite golfers have been shown to possess more of these unique physical characteristics than standard golfers.2

The demands of high-level golf have increased substantially over the last 20 years with elite golfer's travelling across the world to compete in prestigious tournaments for large amounts of money. It is vital that every element of a golfers short and long-term preparation (including their warm-up pre play), allows them to perform to the highest levels of performance at all times.

The importance of appropriate levels of range of movement and flexibility at specific joints and soft tissues in order to perform the golf swing optimally has been well documented.3 However evidence is emerging that suggests while flexibility of musculoskeletal structures in certain parts of the body is important for the golf swing, the immediate effects of passive stretching has been linked with an immediate reduction in specific sports performance, in a variety of sports endeavors, including golf.4–9 It has been demonstrated that there is an immediate reduction in isometric strength immediately after passive stretching.10 Theoretical explanations for this acute decrease in performance include a less compliant muscle tendon unit (MTU), decreased neuromuscular reflex sensitivity, and neural inhibition attributable to the passive stretching.4,6 Interestingly, the amount of elastic energy that can be stored in the MTU is a function of the unit's stiffness.11 This stiffness and subsequent increase in elastic energy and force output can be increased through strengthening/activation of the muscle tendon unit.12

An improvement in performance of the golf swing (including speed, accuracy and distance) has been shown when static stretching is eliminated and only active, dynamic stretches are performed during warm-up.6,8 Strength and resistance training can cause adaptive changes within the nervous system that allow a trainee to fully activate prime movers in specific movements and to better coordinate the activation of all relevant muscles, thereby affecting a greater net force in the intended direction of movement.13 Sale13 demonstrated an increase in peak force associated with both short and long term activation of prime movers, achieved via resistance training, as measured in a study utilizing electromyography.13 Although improving strength and flexibility following longer-term training has been shown to improve general elements of overall golf performance,14–16 no current research exists looking at the immediate effect of resistance training during warm-up on golf performance.

A warm-up can have many different effects on the body in order to prepare it for activity, ranging from raising the heart rate and increasing blood flow to tissues to facilitating nerve transmission and motor unit recruitment.17 There are many different strategies and techniques that can be used during a warm-up, and those chosen may vary depending on the demands of the sport for which an athlete is preparing.

At present the optimal warm-up procedure before golf to improve immediate performance during a maximal drive is unclear, but evidence suggests active dynamic stretching is better than static stretching. At present no studies have been carried out using elite golfers in order to assess the immediate performance benefits of muscle activation through resistance exercises. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the effects of three different warm-up programs (active dynamic and two different combined active dynamic and resistance exercise programs) on immediate performance of a maximal golf drive.

METHODS

Study Population

Fifteen elite male competitive golfers (N=15) (professional or amateur with handicap below 2) between the ages of eighteen and forty were recruited through an opportunity sample of convenience and gave written informed consent to participate. Subjects were screened using eligibility and a medical questionnaire to meet the study criteria, which included having no current injuries, were in a stable training or competitive period, and were already involved in a regular strength and conditioning program. Of the 15 initial participants, 12 completed the study (N=12). Two withdrew due to injury sustained outside of the study and one withdrew due to not being able to complete all 3 sessions in the 4 week time period.

Study method

The participants attended the study venue on three separate, non-consecutive days (max of 1 hr required at each session) over a maximum 4-week period at the Sheffield Hallam University Centre for Sports and Exercise Science Research laboratory. Medical screening questionnaires were completed for each participant at the start of each session. The set up for the exercises and collection of data was identical at each session for each participant. At every session there were two researchers present for safety and to have one person supervising the warm-up with the participant and one person carrying out data collection (blinded to the warm-up program) in order to reduce the chance of research bias. The participants randomly selected one warm-up program from three numbered cards and then carried out one of the three warm-up programs shown below, during each of the three sessions:

Active Dynamic warm-up program. (AD)

Ten practice swings with 1.13-kg weighted club (Momentus)

Three full-swing shots with sand wedge

Three full-swing shots with 8-iron

Three full-swing shots with 4-iron

Three full-swing shots with fairway metal wood

Three full-swing shots with driver

(Active Dynamic stretching warm-up progression with various golf clubs as used by Gergley)6

Active Dynamic warm up program PLUS 10 minute functional resistance warm-up using Theraband® (FR).

Theraband® (red) with rotational trunk movement in standing × 10 bilat

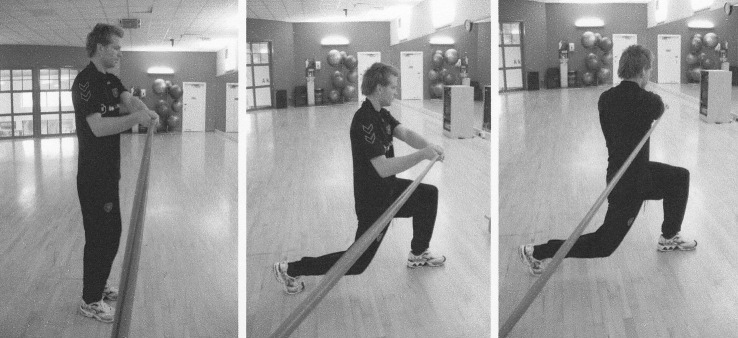

Theraband® (red) with standing lunge and rotational trunk movement × 10 bilat (see photo 1)

Theraband® (red) right arm cross chest adduction and internal rotation with body rotation × 10

Theraband® (red) left arm external rotation and shoulder abduction with rotation × 10

Theraband® (red) with wood chop from right and left trunk rotation × 10

Each exercise repeated × 2 sets

Figure 1.

Active dynamic warm-up program PLUS 10 minute linear based multi-joint strength program using weighted bar. (WT)

Barbell dead lifts with 20 kg bar × 10

Barbell snatches with 15 kg bar × 10

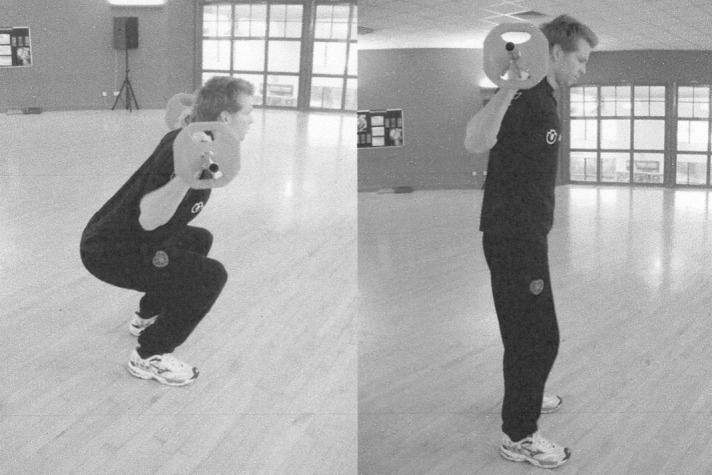

Barbell squat with 20 kg barbell × 10 (see Photo 2)

Bench press with 20 kg Bench press × 10

Standing Bent over row with 20 kg barbell × 10

Each exercise repeated × 2 sets

Figure 2.

The two different forms of resistance training programs used in this study have both been shown to have positive effects on strength and performance in golf and other sports when performed over longer periods of conditioning training.15,16,18–20 Linear multi-joint strengthening using weights was chosen for one resistance warm-up as theory suggests this creates a stiffening of the MTU to allow it to store elastic energy,4,6,13 which may help prepare the musculoskeletal system for the explosive power action of the golf swing. This type of training has also been used in other studies investigating the effect of longer term strengthening programs using key muscles/muscle groups involved in the golf swing, that have subsequently shown an improvement in overall golf performance as measured by handicap reduction. The functional resistance program was chosen as muscle recruitment provided by elastic resistance band exercises may result in improved performance through the activation of muscle recruitment patterns used in the golf swing13 as well as stiffening the MTU. Red theraband® was chosen as it was felt this strength of band would give sufficient resistance to create adequate activation of muscle recruitment patterns and stiffening of the MTU, without exerting high levels of resistance on the musculoskeletal system before a maximal effort golf swing, as may have happened if a stronger resistance band was used. The weight of bar and repetitions for the linear weight warm-up was selected for the same reasons.

Following completion of each warm-up routine the participant then went through their normal pre-shot routine as if they were preparing for competition and then hit ten maximum effort drives. Each of the ten drives was analyzed using Flightscope® radar technology (EDH, Orlando, Florida, USA, Kudo 2009 model). Participants had one minute rest intervals between each shot and were asked after each shot if they felt like it was a consistent ball strike (CBS), which was answered ‘yes' or ‘no’ (see Appendix 1 for standard CBS protocol). Information relating to performance factors for each shot was collected via the Flightscope® for parameters including maximum club head speed (MCHS), maximum driving distance (MDD), smash factor (SF) and driving accuracy (DA). The performance factors measured are important pieces of information taken from the swing data, relating to the forces, control, and subsequent outcome that a golfer has over the golf club during a swing, as it contacts the ball, and over the ball's final outcome after strike. Smash factor is the ratio between the ball speed and the club speed, it tells us about the centeredness of impact and the solidity of the shot, an important factor relating to performance. These particular factors were chosen as they were the ones used in previous studies6 and are the major performance factors and data relating to a maximal golf drive that are measured by equipment such as Flightscope® and used by professional golfers. No participants had performed any form of exercise in the 24 hours prior to each testing session. All partici-pants agreed not to change their technique/golf swing between sessions and to use their same driver for each session. All participants used brand new Titliest™ Pro V1 balls for each shot at each testing session.

STATISTICS

All data analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 software. All data input was repeated twice to reduce the chance of data input mistakes. A repeated-measures ANOVA test for 3 sample mean values was used to provide a statistical measure of actual mean difference between multiple applications. Paired t-tests were then performed between each of the three sets of data to identify within group differences between the data for each warm-up program.

RESULTS

Results of the repeated measures ANOVA test revealed a statistically significant (p<0.05) difference for the MDD (p=0.042), SF (p=0.004) and CBS (p=0.004) between the three warm-up programs (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were found between the warm-ups for MCHS and DA, however the mean results did show improved figures for these two performance factors with the FR warm up. Paired t-tests between the three warm-up groups were used to further investigate the three factors of performance that showed statistically significant differences. Analysis showed that the functional resistance (FR) warm-up had increased MDD by 14.98 yards (+5.59%) over AD (p=0.013) and 12.98 yards (+4.81%) over the WT warm-up group (p=0.05). The SF for the FR warm-up was increased by 0.021 (+1.47%) compared to the AD (p=0.003) and by 0.01 (+0.69%) over the WT group (p=0.011). The CBS was increased in the FR group by 1.08 (+13.36%) over the AD warm-up group (p=0.002) and by 0.99 (+12.11%) over the WT group (p=0.007). No statistically significant differences were seen between the AD and WT warm-up programs for the MDD, SF and CBS.

Table 1.

Mean values and Standard Deviation (SD) for the five different factors of performance during a maximal golf drive after three different warm-up programs.

| Warm Up Program | Maximum Clubhead speed (MCHS) (miles/hr) | Maximum driving distance (MDD) (yards) | Smash Factor (SF) | Driving accuracy (DA) (Yards from target) | Consistent Ball strike (CBS) (Yes-out of 10) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Active Dynamic (AD) | 110.96 | 4.245 | 267.29 | 13.51 | 1.422 | .01865 | 10.26 | 6.03 | 8.08 | .668 |

| AD with Functional resistance with Theraband (FR) | 112.98 | 4.519 | 282.27 | 12.66 | 1.443 | .01435 | 7.85 | 3.11 | 9.16 | .937 |

| AD with Weights (WT) | 112.38 | 3.69 | 269.39 | 13.89 | 1.433 | .01497 | 8.35 | 4.42 | 8.17 | .834 |

| p-value | 0.073 | 0.042* | 0.004* | 0.470 | 0.004* | |||||

Indicates statistically significant differences.

Table 2.

Results of the paired samples t-test for Maximum Driving Distance (MDD) for each of the three warm ups.

| Paired Differences | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (yards) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Pair | ST active dynamic | −14.97167 | 17.51003 | 5.05471 | −26.09701 | −3.84632 | −2.962 | 11 | .013 |

| 1 | MDD - ST theraband MDD | (−5.59%) | |||||||

| Pair | ST active dynamic | −2.09750 | 9.36620 | 2.70379 | −8.04850 | 3.85350 | −.776 | 11 | .454 |

| 2 | MDD - ST weights MDD | (−0.785%) | |||||||

| Pair | ST theraband MDD - | + 12.8741 | 20.38379 | 5.88429 | −.07708 | 25.82541 | 2.188 | 11 | .051 |

| 3 | ST weights MDD | (+4.81%) | |||||||

DISCUSSION

The aim of this investigation was to identify if the addition of a resistance training program (FR or WT) to an active dynamic (AD) stretching program during the warm-up routine of elite golfers would result in improved golf performance in relation to maximum clubhead speed (MCHS), maximal driving distance (MDD), smash factor (SF), driving accuracy (DA) and consistent ball strike (CBS). The results revealed significant improvement in CBS, MDD and SF when a FR program is combined with an AD warm-up compared to an AD warm-up alone or when combined with a WT program during the warm-up. For the performance factors of DA and MCHS there were no significant differences between any of the three different warm-up groups. For the factors of MDD, CBS and SF there was no difference in performance seen between the AD and WT warm-up groups.

As there has been no previous research into performance of different resistance and stretching warm-ups on immediate golf performance it is difficult to draw comparisons to other studies. Strength training using both Theraband®-based functional resistance and weight based multi-joint methods over a longer period of weeks have been shown to have positive outcomes on strength and performance in golf, tennis and baseball.19–21 Tennis and baseball are both relatively comparable sports to golf in that they involve explosive power, swinging, and rotational movements. Both of these training methods have varying effects on the neuromusculoskeletal system but have created similar results in strength and performance improvement in certain sports. There is an increase in peak force associated not just from long-term activation of prime mover muscles through resistance training, but also in the immediate short term.13 However, the results of the current study suggest that performing a functional resistance warm-up program using Theraband® had a statistically significant increase in MDD, CBS and SF during the performance of a maximal golf drive as compared to performing a linear multi-joint weight resistance program. Functional resistance training aims to enhance the coordinated working relationship between the muscular and nervous systems and the force-producing capabilities of a muscle group or motor pattern22 for a particular task. This may be a reason why activating functional movement and motor patterns involved in the golf swing during the FR warm-up in this study led to improvements in certain factors of the performance of a maximal golf drive, as opposed to the resistance based warm-up of the musculoskeletal system using weights in non functional movement patterns.

Performing sustained static stretches causes immediate reductions in performance of a maximal golf drive compared to when performing an active dynamic warm-up stretching program.6 Gergley6 suggested that “the skeletal muscles were normally and sufficiently innervated by the central nervous system but that less force was transferred to the golf club because of slack in the tendon following a static stretch”.p866 In addition, altered neurological activity following the static stretch may have caused the skeletal muscles to fire without synchronization or adequate action potential, thus reducing coordination and/or force production, and that the transfer of force from the skeletal muscles to the golf club by the neurological system were temporarily impaired by the static stretching treatment.6 An explanation for the improvement in performance seen in this study by the addition of a FR program to an AD warm-up as opposed to an AD or WT program is that the stiffening of the MTU and task specific functional resistance exercises led to improved neurological activity of the skeletal muscles. This in turn may have resulted in greater coordination, force production, and performance of the golf swing in relation to CBS, MDD and SF.

Although no previous studies into the effects of strength training on immediate golf performance have been performed, the findings of this study are similar to that of other studies examining the effect of linear multi-joint resistance exercises on immediate performance of other activities, which showed no difference between active stretching, linear multi-joint high and low repetition and load exercises on standing jump and sprinting activities.23–25

Based on the requirements of the golf swing and the physiological understanding of the musculoskeletal system and the results of this study, it would appear that a warm-up program should include activation of key rotational and stability muscle groups and motor patterns, as well as dynamic flexibility, in order to prepare the upper body, trunk and legs for explosive power production. This may be achieved by stiffening the muscle tendon units (MTU), improving force output13 and enhancing neuromuscular response such as improved synchronization and more efficient muscle recruitment patterns26,27 with the use of functional resistance exercises. The current results showed that there were no statistically significant differences found between the MCHS and DA for any of the three warm-up groups, indicating that the addition of a resistance program to an active dynamic stretching warm-up had no effect on the performance of these two factors. Although no statistically significant difference was found for MCHS and DA factors of golf performance between the three groups, the FR warm-up group did produce better mean results for these factors than the other two groups (see Table 1). Depending on the effect required by the elite golfer on their performance those wishing purely to achieve optimum driving accuracy rather than greater driving distance may only wish to perform an active dynamic warm-up to optimize time spent doing a warm-up.

The golf swing is a closed kinetic chain activity occurring mainly in the transverse plane making it a unique skill and activity.28 A round of golf during professional competition can take in excess of 5 hours and involve long periods of inactivity followed by short periods of high intensity, explosive effort requiring a combination of power, flexibility, strength and skill. There are many other factors relating to performance in elite golf other than performing a maximal golf drive, such as the total score per round, putts per round, and external variations including the weather and equipment to name a few, which make it difficult to evaluate the effect of one particular intervention on overall golf performance in elite golfers. It is unknown from these findings what the latent effects of these warm-up programs are over longer time periods.

This study was specific to the immediate effects on performance of a maximal golf drive of elite male golfers between the ages of 18–40. Therefore, conclusions should not be drawn from the findings in relation to other sports or groups or aspects of performance relating to golf. Further research in this area is required on larger numbers and different groups in order to apply results to the wider population of golfers.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The implications for physiotherapy practice from this study are that the warm-up strategies utilized immediately before golf are important and do have an effect on the immediate performance of a maximal golf drive. Given the large amount of prize money and pressures in professional golf every element of their preparation and performance is vitally important. Static stretching should be avoided as it has been shown to reduce immediate performance.4–10 Instead, functional resistance exercises utilizing rotational trunk movements (that mimic motor patterns and muscles used in the golf swing) when combined with AD exercises led to improved immediate performance of certain factors of the maximum golf drive compared to combined WT and AD or AD by itself. The results of this study will be incorporated into the daily physiotherapy practice of the author with elite golfers when helping them devise and carry out their warm-up programs. More research is required to identify the latent effect of these warm-up programs, the optimum duration of the warm-up, and the optimum components of the exercises such as repetitions, level of resistance, and the equipment used. Additionally, further research involving the use of these types of exercises in structured training programs over longer periods of time and their effect on performance would also be beneficial.

CONCLUSION

Performing a combined AD and FR warm-up with Theraband® leads to significant increase in immediate performance during the golf drive relating to maximal driving distance, smash factor, and consistent ball strike in elite male golfers as compared to performing an AD warm-up by itself or a combined AD with WT warm-up. No statistically significant difference was observed between the three warm up groups when looking at immediate effect on driving accuracy or maximum club head speed. The addition of functional resistance activities to active dynamic stretching has immediate benefits to elite male golfers in relation to some factors of their performance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lennon HM. Physiological profiling and physical conditioning for elite golfers. In: Cochran AJ. ed. Science and golf: Proceedings of the Scientific Congress of Golf 1998:58–64 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sell TC, Tsai YS, Smoglia JM, et al. Strength, Flexibility, and balance Characteristics of Highly Proficient Golfers. J Strength Cond Res 2007;21:1166–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon BS, Moir GL, Davis SE, et al. An investigation into the relationship of flexibility, power and strength to club head speed in male golfers. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:1606–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cromwell A, Nelson AG, Heise GD, et al. Acute effects of passive muscle stretching on vertical jump performance. J Hum Mov Stud 2001;40:307–324 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher IM and Jones B. The Effect of different Warm-Up Stretch Protocols on 20 Meter sprint performance in trained Rugby Union Players. J Strength Cond Res 2004;18:885–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gergley JC. Acute Effects of passive stretching during warm up on driver Club head Speed, Accuracy, and consistent Ball Contact in Young Male competitive Golfers. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:863–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gremion G. Is stretching for sports performance still useful? A review of the literature. Rev Med Suisse 2005;1:1830–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran KA, Mcgrath T, Marshall BM, et al. Dynamic Stretching and golf swing performance. Int J Sports Med 2009;30:113–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrier I. Does stretching improve performance? A systematic and critical review of the literature. Clin J Sports Med 2004;14:267–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowles JR and Sale DG. Time Course of strength deficit after maximal passive stretch in humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997;29:5:S26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingen GJ. An alternative view of the concept of utilization of elastic energy in human movement. J Hum Mov Sci 1984;3:301–336 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shorten MR. Muscle elasticity and human performance. Med Sports Sci 1987;25:1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sale DG. Neural adaptation to resistance training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1988;20:135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doan BK, Newton RU, Kwon YH, et al. Effects of Physical Conditioning on intercollegiate Golfer performance. J Strength Cond Res 2006;20:62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fletcher IM and Hartwell M. Effect of an 8 week combined weights and Plyometrics training program on golf drive performance. J Strength Cond Res 2004;18:59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westcott WL, Dolan F and Caricchi T. Golf and strength training are compatible activities. Strength Cond J 1996;18:54–56 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedrick A. Physiological responses to warm-up. J Strength Cond Res 1992;14:25–7 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lephart SM, Smoliga JM, Myers JB, et al. An Eight-week Golf specific Exercise program improves Physical characteristics, swing mechanics and golf performance in recreational golfers. J Strength Cond Res 2007;21:860–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page PA, Lambeth J, Abadie B, et al. Posterior Rotator cuff Strengthening Using Theraband in a functional diagonal pattern in collegiate baseball pitchers. J Athl Train 1993;28:346–354 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treiber FA, Lott J, Duncan J, et al. Effects of Theraband and lightweight dumbbell training on shoulder rotation torque and serve performance in college tennis players. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:510–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fradkin AJ, Sherman CA and Finch CF. Improving Golf performance with a warm up conditioning programme. Br J Sports Med 2004;38:762–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant CX. 101 Frequently Asked Questions about “Health & Fitness” and “Nutrition & Weight Control” 1999. Sagamore Publishing.

- 23.Koch AJ, O'Bryant HS, Stone ME, et al. Effect of Warm up on the standing Broad Jump in Trained and Untrained Men and women. J Strength Cond Res 2003;17:710–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott SL and Docherty D. Acute effects of heavy preloading on Vertical and Horizontal Jump Performance. J Strength Cond Res 2004;18:201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez–Rave JM, Machado L, Navarro Valdivielso F, et al. Acute effects of heavy Load exercises, stretching exercises and Heavy Load plus stretching exercises on Squat Jump and countermovement Jump Performance. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:480–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komi PV. Training of Muscle strength and power: interaction of neuromotoric, hypertrophic and mechanical factors. Int J Sports Med 1986;7:10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milner-Brown HS and Lee RG. Synchronization of human motor units: possible roles of exercise and supraspinal reflexes. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1975; 38:245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maddalozzo GF. An anatomical and biomechanical analysis of the full golf swing. Natl Strength Cond Assoc J 1987;9:77–79 [Google Scholar]