Abstract

A 67-year-old woman presented with synchronous breast and colonic tumours, in the absence of family history. Following multidisciplinary discussion, the patient was started on endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Initial surgical management consisted of right hemicolectomy together with segmental resection of a serosal deposit adherent to the distal ileum, for a moderately differentiated pT4NO caecal carcinoma. Three months later, right mastectomy and axillary clearance confirmed node positive invasive ductal carcinoma. The original treatment plan was to prioritise adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer postmastectomy. However, the subsequent CT finding of an enlarged, suspicious mesenteric lymph node mass on repeat staging raised concern regarding its origin. Image-guided biopsy revealed metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma and the patient was switched to a colon cancer chemotherapy regime. Following adjuvant chemotherapy for colonic carcinoma, an en-bloc surgical resection of the enlarging metastatic nodal mass was performed with clear resection margins. The patient is currently asymptomatic.

Background

The management of synchronous, solid tumours of differing primary locations represents an interesting clinical scenario. A decision is necessary regarding which tumour to treat initially, and how to stratify further treatments according to individual tumour risk. This process involves multidisciplinary team (MDT) input from oncologists, surgeons, radiologists and clinical pathologists to ensure optimum patient outcome. This case explores the issues of initial treatment and subsequent alterations in therapeutic plan based on the unexpected discovery of a rapidly enlarging mesenteric lymph node mass. The management of this patient represents a clinical challenge for which there are no strict guidelines. It also highlights the important role of continuous multidisciplinary discussion and management in order to ensure favourable patient outcome.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old woman presented with a 3-week history of general malaise and abdominal pain without change in bowel habit. Her medical history included hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and osteoarthritis. Surgical history was limited to right total knee replacement. Her regular medications included propranolol, valsartan, aspirin, bendroflumethiazide and omeprazole. She was an ex-smoker of 9 years with a 30 pack-year history, and drank alcohol occasionally. Notably, she had no family history of breast or colorectal cancer. Physical examination revealed a clinically suspicious right breast lump. There were no further relevant clinical findings.

Investigations

Haematological investigations revealed a hypochromic, microcytic anaemia with haemoglobin of 6.7 g/dL, and elevation of white cell count and C reactive protein to 20×109/L and 236.9 mg/dL, respectively. Breast investigations revealed the presence of a 3.9 cm invasive ductal carcinoma (oestrogen receptor (ER) +ve, progesterone receptor (PR) +ve, Her-2/neu −ve) with axillary lymph node metastases. Staging investigations, including CT (thorax/abdomen/pelvis) and isotope bone scintigraphy, were negative for distant breast metastases. However, a coexisting caecal neoplasm was clearly identified on axial imaging of the abdomen. This was considered to be at short-term risk of obstruction.

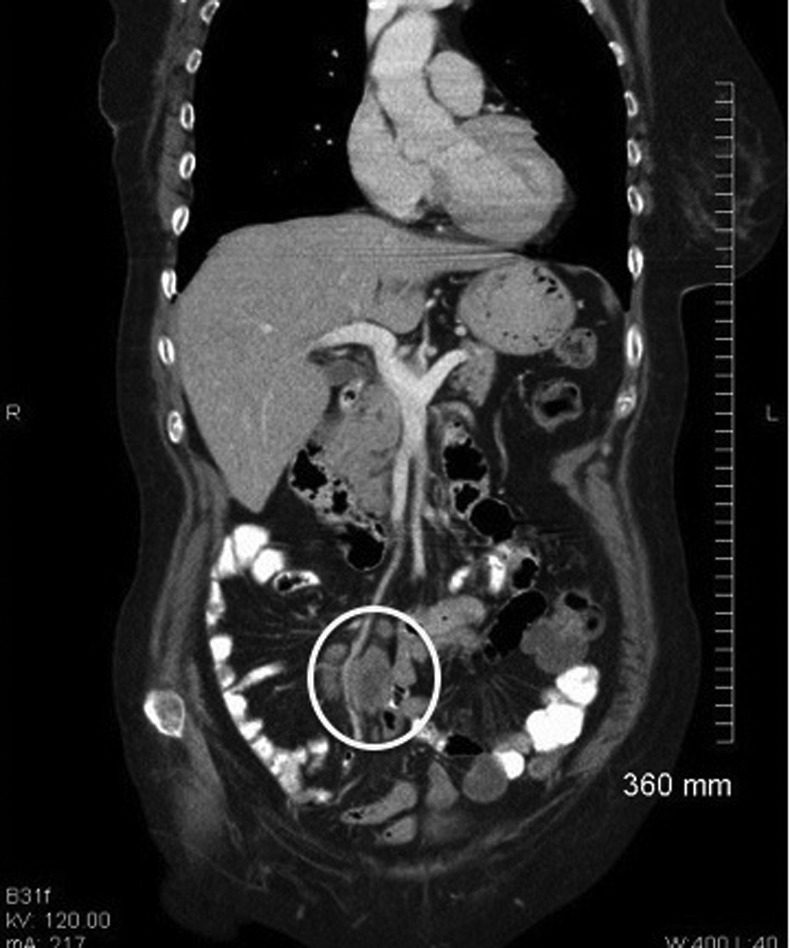

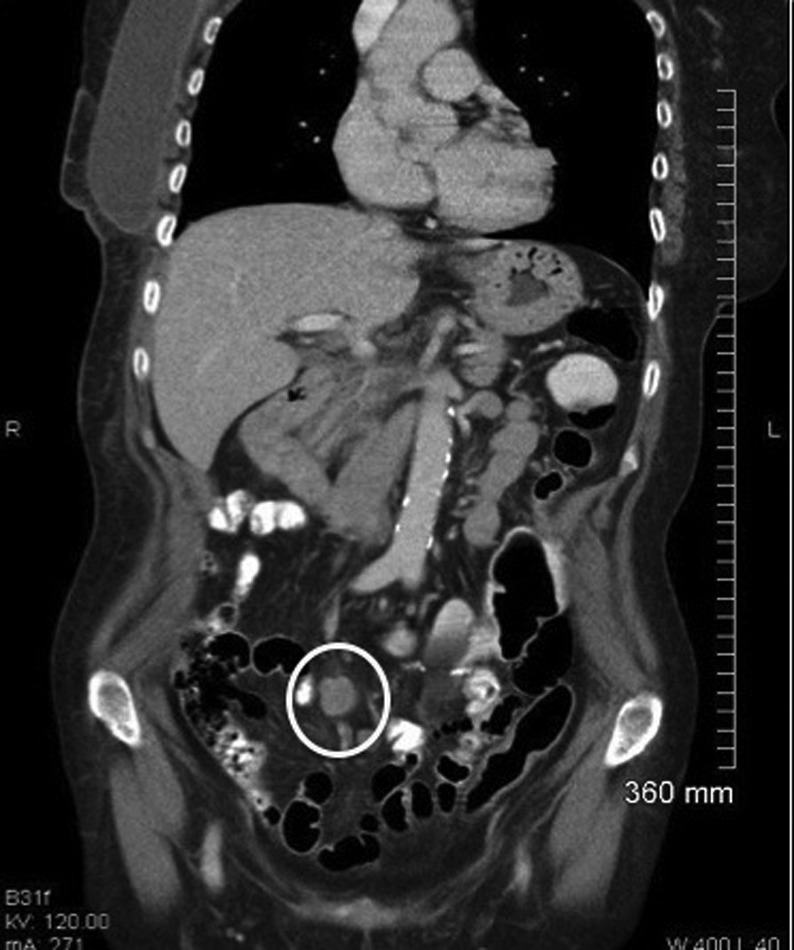

Following multidisciplinary discussion and interval resection of both primary tumours, a repeat staging CT scan revealed an enlarging mesenteric lymph node mass (figure 1). This was investigated further by image-guided biopsy and demonstrated metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma consistent with the caecal primary. The patient was therefore started on a chemotherapeutic regime directed towards the management of metastatic colon cancer. A further staging CT scan revealed significant enlargement of the lymph node mass despite focused adjuvant chemotherapy, precipitating en bloc resection in due course (figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Mesenteric lymph node mass discovered on staging CT scan 1 month post mastectomy.

Figure 2.

Enlarging mesenteric lymph node mass despite adjuvant chemotherapy.

Treatment

The patient was initially started on Letrozole (an aromatase inhibitor) and then proceeded to a right hemicolectomy, with limited segmental small bowel resection, less than 1 month after her diagnoses. At laparotomy, there was a serosal tumour deposit involving a segment of distal ileum located 60 cm proximal to the caecal tumour. All gross disease was resected at the time of surgery. The colonic tumour extended through the entire medial wall of the caecum and 19/19 nodes were negative for colonic adenocarcinoma, making this a pT4N0 tumour, that is, stage IIB colon cancer. Histology of this serosal deposit revealed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, morphologically similar to the primary tumour in the caecum. The mucosa, submucosa and muscular layer of the small bowel were histologically normal and not infiltrated by tumour. Histological examination also demonstrated focal microscopic tumour involving one of the small bowel mesenteric resection margins. The resected specimens were also noted to be microsatellite instability (MSI) positive.

Following colon surgery, focus returned to the synchronous right breast cancer. Three months after her initial presentation, the patient underwent a right mastectomy and axillary clearance for a grade III, ER/PR positive, Her-2/neu negative, multifocal invasive ductal carcinoma with extensive lymph node involvement. Of 17 lymph nodes, 16were positive for metastatic carcinoma making this a pT3N3A breast cancer. Having started Letrozole at initial presentation, the agreed treatment plan was to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer.

A staging CT scan of thorax/abdomen/pelvis was performed 1 month postmastectomy and this led to the finding of a new mesenteric lymph node mass, most likely representing progression of colonic disease. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the lymph node mass was performed revealing metastatic adenocarcinoma of colonic origin.

Following further MDT review, the patient was started on a FOLFIRI chemotherapy regime for treatment of metastatic colon adenocarcinoma. The mesenteric lymph node mass continued to enlarge despite adjuvant chemotherapy (as confirmed by follow-up CT scan performed after a 4 months interval) and the case was referred back for MDT discussion. Given the patient's good performance status, a recommendation to attempt full surgical clearance of this metastatic mesenteric tumour deposit was made. Nine months after the original right hemicolectomy and segmental small bowel resection, the patient was scheduled for removal of the mesenteric lymph node mass. Further surgical exploration resulted in a successful outcome with resection of a 7×5 cm mesenteric tumour deposit, which was approaching the superior mesenteric artery at the root of the small bowel mesentery. In order to ensure resection of all visible disease, it was necessary to resect a 60 cm segment of ileum, which included the site of the previous ileocolic anastomosis. The final histology report confirmed metastatic colonic malignancy with clear resection margins.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient remains well 6 months postresection of the mesenteric lymph node mass, without CT evidence of disease recurrence, and has started on adjuvant FOLFOX and Cetuximab (tumour type is KRAS wild-type). Endocrine therapy continues in the absence of radiological evidence of progression of breast cancer. She has maintained a good performance status given her original presentation and continues on a programme of 6 monthly clinical and radiological follow-up as recommended by the MDT.

Discussion

Synchronous tumours are defined as a separate second tumour, discovered within 2 months of primary tumour diagnosis and have a reported frequency of 3–5%.1 Two tumours of differing primary origin frequently prompt consideration of an underlying familial or genetic predisposition. The occurrence of synchronous breast and colon carcinoma has been described in the literature and controversy remains as to the relationship between the two. A recent study has demonstrated a specific genetic mutation, CHEK2*1100delC,2 that identifies patients with a hereditary breast and colorectal cancer phenotype and perhaps in the future such testing will become applicable to patients such as in our case. Interestingly, the caecal tumour resected in our patient was MSI positive. MSI is associated with the familial Lynch syndrome or hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). The Amsterdam II Criteria used to diagnose HNPCC syndrome, however, does not include breast cancer as one of the cancer subtypes found in this syndrome and recent evidence supports the view that breast cancer is unrelated to this syndrome. Thus, in our patient's case, it is likely that she developed sporadic synchronous primary tumours that were not related to any familial predisposition. Both tumours were diagnosed on a background of the patient's initial presentation with iron deficiency anaemia. A decision was made to proceed to resection of her caecal carcinoma after starting of endocrine therapy for the synchronous breast cancer.

All gross colonic disease was resected at laparotomy. Histology revealed a stage II B colon cancer with high risk features; T4 disease with a serosal deposit adherent to small bowel with a positive focal microscopic small bowel mesenteric margin. However, there was no evidence of lymphatic invasion with 19 lymph nodes free of tumour, exceeding the internationally recommended guideline of a minimum of 12 lymph nodes harvested.3 A decision was then made to proceed with surgical management of the synchronous right breast carcinoma. Further scheduled imaging played a key role in alerting the MDT to the re-emergence of tumour deposit within the mesentery in an asymptomatic patient where the focus was now on adjuvant treatment of her synchronous breast malignancy. The CT images clearly documented a new mesenteric lymph node mass that was not present at the time of laparotomy and developed within a short interval. Studies have demonstrated that isolated local and regional recurrences occur in approximately 3–12% of patients who have undergone a primary colon cancer resection with curative intent.4 5 This newly resected mesenteric lymph node mass upstaged the patient's colonic malignancy in accordance with the 2010 TNM staging system which uses the term ‘satellite tumour deposits’ to designate discrete rounded nodules of tumour of any size within the pericolic or perirectal fat or in adjacent mesentery.6 Satellite tumour deposits are considered the equivalent of nodal metastases (a lymph node replaced by tumour), even if they lack residual nodal architecture, and are staged as N1c disease in the absence of other nodal metastases, thus upstaging our patient's disease from N0 to N1c. The presence of these mesenteric tumour deposits is a strong adverse prognostic feature.7 8

Evidence suggests that patients with an isolated locoregional recurrence should be evaluated for salvage resection. The most important prognostic factor remains the ability to achieve an R0 resection (microscopic negative margins). Two prospective studies have demonstrated the benefit of surgical reintervention in order to achieve an R0 resection, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 43% to 57%, compared with 5% survival for those patients with an incomplete resection or no resection.9 10 Fortunately in our case, the patient has now achieved negative microscopic resection margins. While guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases, they do not address the utility of chemotherapy after resection of an isolated local recurrence.11 Further treatment should be individualised and the role of the MDT team is invaluable under these circumstances.

Learning points.

Synchronous breast and colon malignancies are rare, particularly in the absence of family history.

Continuous multidisciplinary review is of paramount importance in directing treatment in complex cases.

Despite a negative mesocolic lymph node harvest, the presence of a positive microscopic small bowel mesenteric margin may result in locally recurrent colonic disease within a short time frame despite adjuvant chemotherapy.

In the case of isolated locoregional recurrence of colon cancer, salvage surgery is appropriate provided clear histological margins can be achieved.

Footnotes

Contributors: LH was involved in preparation of manuscript, IR was involved in collection of cases and preparation of manuscript. WQ contributed by critically reviewing the paper. KB critically reviewed and prepared the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bittorf B, Kessler H, Merkel S, et al. Multiple primary malignancies: an epidemiological and pedigree analysis of 57 patients with at least three tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol 2001;2013:302–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meijers-Heijboer H, Wijnen J, Vasen H, et al. The CHEK2 1100delC mutation identifies families with a hereditary breast and colorectal cancer phenotype. Am J Hum Genet 2003;2013:1308–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shia J, Wang H, Nash GM, et al. Lymph node staging in colorectal cancer: revisiting the benchmark of at least 12 lymph nodes in R0 resection. J Am Coll Surg 2012;2013:348–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris GJ, Senagore AJ, Lavery IC, et al. Factors affecting survival after palliative resection of colorectal carcinoma. Colorectal Dis 2002;2013:31–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willett CG, Tepper JE, Cohen AM, et al. Failure patterns following curative resection of colonic carcinoma. Ann Surg 1984;2013:685–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;2013:1471–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein NS, Turner JR. Pericolonic tumor deposits in patients with T3N+MO colon adenocarcinomas: markers of reduced disease free survival and intra-abdominal metastases and their implications for TNM classification. Cancer 2000;2013:2228–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo DS, Pollett A, Siu LL, et al. Prognostic significance of mesenteric tumor nodules in patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Cancer 2008;2013:50–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowne WB, Lee B, Wong WD, et al. Operative salvage for locoregional recurrent colon cancer after curative resection: an analysis of 100 cases. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;2013:897–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sjovall A, Granath F, Cedermark B, et al. Loco-regional recurrence from colon cancer: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;2013:432–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. http://www.nccn.org