Abstract

Wnt/β-catenin signalling is central to development and its regulation is essential in preventing cancer. Using phosphorylation of Dishevelled as readout of pathway activation, we identified Drosophila Wnk kinase as a new regulator of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling. WNK kinases are known for regulating ion co-transporters associated with hypertension disorders. We demonstrate that wnk loss-of-function phenotypes resemble canonical Wnt pathway mutants, while Wnk overexpression causes gain-of-function canonical Wnt-signalling phenotypes. Importantly, knockdown of human WNK1 and WNK2 also results in decreased Wnt signalling in mammalian cell culture, suggesting that Wnk kinases have a conserved function in ensuring peak levels of canonical Wnt signalling.

Keywords: Dishevelled, Drosophila , Gordon syndrome, Wnk kinase, Wnt signalling

Introduction

Wnt/Wingless (Wg) growth factors signal through either canonical Wnt (Wg)-Frizzled (Fz)/β-catenin [1, 2] or noncanonical Wnt pathways (that is, Wnt/Fz-planar cell polarity (PCP)), regulating polarization of cells in the plane of the epithelium [3]. These pathways are highly conserved and diverge downstream of the cytoplasmic component Dishevelled (Dsh in Drosophila, Dvl1-3 in mammals). In many tissues, both pathways act in the same cells and tight regulation of Wnt/Fz-Dsh signalling is essential.

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling controls the specification of the dorsal–ventral (D–V) vertebrate axis, cell proliferation and maintenance of stem cells. In addition, aberrant canonical Wnt signalling causes cancer (reviewed in Clevers and Nusse[1]). In Drosophila, canonical Wnt signalling is required for embryonic segmentation, eye specification and formation and patterning of legs and wings [2].

Two Wnt co-receptors are Frizzled (Fz or Fzd) family members and the low-density lipoprotein transmembrane receptor-related protein 5 and 6 (LRP5/6; Arrow in Drosophila) [1]. The cytoplasmic adaptor protein Dsh/Dvl together with members of the degradation complex (Axin, the tumour suppressor protein APC and GSK3β), and casein kinase 1 (CK1) family members are essential for regulation of the cytoplasmic levels of β-catenin (Armadillo/Arm in Drosophila) [1, 2]. Wnt binding to Fz and LRP5/6 induces the formation of a multiprotein complex (signalosome), ultimately stabilizing β-catenin allowing it to enter the nucleus to co-activate transcription with the transcription factor TCF/LEF (T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor) [1].

In Drosophila, similar to wg mutants, maternal-zygotic dsh mutants show segmentation defects and hypomorphic dsh mutations lead to defects in wing specification [4]. On signalling activation, Dsh becomes highly phosphorylated [5], although the functional significance of Dsh phosphorylation has remained unclear [6–8]. In mammalian and Drosophila cell culture, and in Drosophila in vivo, Dsh hyperphosphorylation correlates with Wnt pathway activation [9–11]. Using a Dsh gel-shift-based screen, we identified Drosophila Wnk (with no lysine (K) kinase; CG7177), characterized by an atypical placement of a catalytic lysine in the kinase domain, as a new and unexpected modulator of canonical Wnt signalling. We show that wnk loss-of-function (LOF) shows specific canonical Wnt/β-catenin phenotypes in the Drosophila wing. In addition, loss of wnk suppresses overactivation of Wnt signalling induced by overexpression of dFz2 or Dsh. Our data indicate that the activity of WNK is required for peak levels of Wnt/β-catenin signalling, as its loss reduces the expression of Senseless, a direct transcriptional Wnt target. Importantly, regulation of Wnt signalling by Wnk is conserved in mammals and probably acts through the intermediate kinases OSR1/SPAK (Fray in Drosophila) [12].

Results

Wnk affects Dishevelled phosphorylation

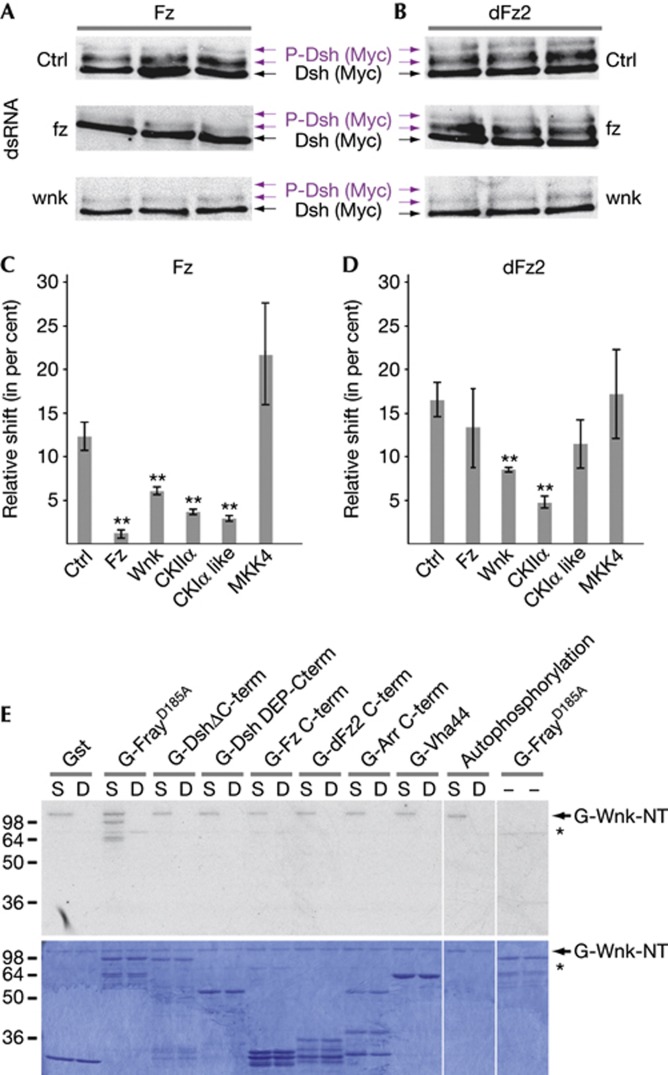

As in mammalian cells, activation of Wnt signalling correlates with Dsh phosphorylation in Drosophila in vivo and in cell culture [5, 9, 13]. Drosophila Fz and dFz2 induce a dose-dependent mobility shift of Dsh on western blots [8, 13], allowing to systematically assess direct or indirect effects of knockdown of each kinase on Dsh phosphorylation and thus to identify new Wnt signalling regulators (Fig 1A–D; Dsh phosphorylation was quantified and compared with control dsRNAs by calculating the ratio of shifted (phosphorylated) to total Dsh protein bands; see Methods). Our screen identified several CK family members, known to reduce Dsh phosphorylation in cell culture (Fig 1C,D) [5, 13]. We also found that knockdown of Wnk kinase (CG7177) led to a significant decrease in Dsh phosphorylation compared with controls when induced by Fz or dFz2 (lowest panels in Fig 1A,B, quantified in C,D).

Figure 1.

wnk regulates Wnt signalling in S2 cells. Compared with Lasp control dsRNA (Ctrl), Fz (A) and dFz2 (B) induced Dsh phosphorylation (purple arrows indicate phosphorylated Dsh) in S2 cells (top panel) is specifically reduced by dsRNA-mediated knockdown of wnk (lower panels). Fz, but not dFz2-induced Dsh phosphorylation is reduced by knockdown of Fz (middle panels), showing specificity of the assay. (C,D) Quantification of the relative Dsh gel-shifts (phosphorylated Dsh to total Dsh; n=3; error bars are s.d.; T-test; **P<0.01). CKIIα and CKIα-like (CG12147) and MKK4 serve as positive and negative controls, respectively. (E) Wnk kinase assays. Indicated proteins were used as substrates for constitutively active (S: S434E) and catalytically inactive (D: D420A) N-terminal Wnk fragments. WnkS434E autophosphorylates, but WnkD420A does not, showing that it is catalytically inactive, as is FrayD185A. Top panel shows autoradiograph of the Coomassie-stained gel below. Asterisk indicates contaminating kinase activity present in some of the Gst protein purifications.

Wnk modifies canonical Wnt/β-catenin phenotypes

In contrast to flies with one wnk gene, mammalian genomes encode four Wnks (WNK1–4; supplementary Fig S1 online) that regulate sodium/chloride co-transporters of the SLC12 family (N(K)CC) and potassium/chloride co-transporters in the kidney [12, 14]. Drosophila wnk is required for neural development and regulates Arrowhead transcription [15, 16], but has not been linked to Wnt signalling.

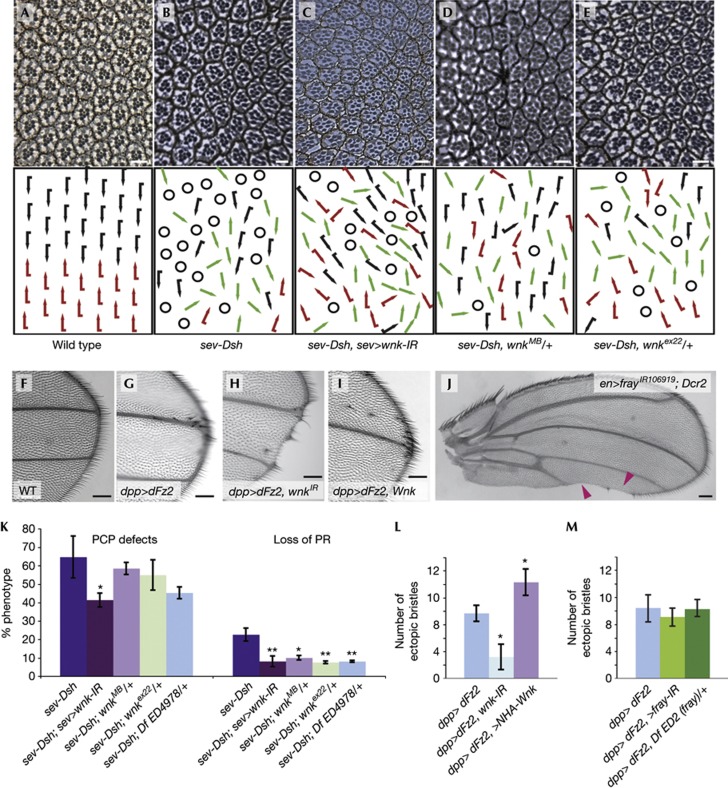

Overexpression of Dsh in the eye using a sevenless enhancer (sev-Dsh) leads to canonical Wg GOF phenotypes characterized by loss of photoreceptors (Fig 2A,B, quantified in Fig 2K; 22.7±3.5%). Overexpression of Dsh also causes PCP defects, including misoriented and symmetric ommatidia (66.4±11.3% of ommatidia with a full photoreceptor complement; Fig 2B,K), reflecting its function in PCP signalling. wnk knockdown by RNAi (under sev-GAL4 control) concomitant with Dsh overexpression resulted in a specific suppression of the sev-Dsh Wg/β-catenin phenotype (Fig 2C, quantified in 2K). A similar suppression was seen using a deficiency Df(3L)ED4978 encompassing wnk (Fig 2K). Loss of Wnk activity did not consistently suppress PCP-specific sev-Dsh GOF phenotypes.

Figure 2.

wnk dominantly suppresses Wnt/β-catenin overactivation. (A–E) Tangential sections of adult eyes with anterior to the left and dorsal up and respective schematic representations. Black and red arrows represent dorsal and ventral ommatidia. Green arrows: symmetrical clusters; circles: ommatidia with incomplete photoreceptor complements. (A) Wild type. (B) sev-Dsh/+; note PCP defects and R-cell loss due to GOF canonical Wnt signaling. Co-expression of sev-Dsh with sev-GAL4>UAS-wnk-IR106928 (C) or reduction of wnk by wnkMB04699/+ (D) or wnkex22/+ (E) specifically suppresses R-cell loss. (F–I) Distal tips of wings. Compared with wild type (F), dpp>dFz2 induces ectopic wing margin bristles (G), a phenotype that is suppressed by RNAi-mediated knockdown of wnk-IR106928 (H). (I) Co-expression of HA-Wnk with dFz2 increases ectopic margin bristles (compare with G; quantified in L). (J) en>frayIR106919 (with UAS-Dcr2) induces loss of wing margin similar to knockdown of Wnk. (K) Quantification of the PCP and R-cell loss of genotypes indicated. To quantify PCP defects, number of chirality flips and symmetrical clusters were scored and compared with chiral ommatidia with a full photoreceptor complement only. n=3 eyes; error bars are s.d.; T-test, *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (L,M) Quantification of ectopic margin bristles of indicated genotypes: Number of ectopic bristles was reduced (from 9.7±1.2 to 3.2±1.9%) and increased (to 14.3±1.9%) with wnk-IR106928 or Wnk overexpression, respectively (L). (M) No significant change was detected by knockdown or copy removal of fray. Error bars are s.d.; T-test; *P<0.001; n=6. Scale bars, 5 μm (A–E) and 0.1 mm (F–J).

In the wing, overexpression of dFz2 driven by decapentaplegic (dpp)-GAL4 along antero-posterior (A-P) compartment boundary leads to overactivation of Wg signalling inducing ectopic margin bristles (Fig 2F,G). wnk-IR106928 suppressed the dpp>dFz2 ectopic margin bristle effect (Fig 2H, quantified in 2L). Such wings also showed a loss of margin (Fig 2H and below). engrailed (en)-GAL4>dFz2 is lethal at 25 °C. Strikingly, en>dFz2 lethality is suppressed by concomitant knockdown with wnk-IR106928 and wings of surviving animals showed partial loss of the wing margin and lacked margin bristles (supplementary Fig S2A online). Our data thus indicate that Wnk acts positively in the regulation of canonical Wnt signalling.

Loss of Wnk causes canonical Wg-signalling phenotypes

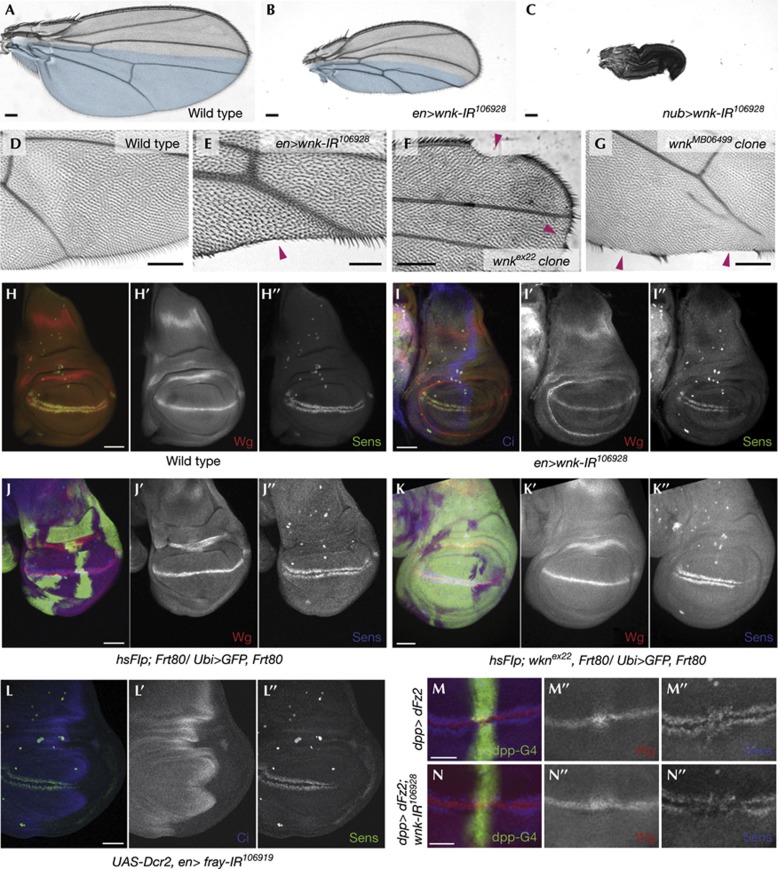

Wg signalling specifies the wing primordium and mediates growth and patterning from the D–V compartment boundary [2] with peak levels required to activate senseless (Sens) to specify wing margin bristles [17]. RNAi-mediated knockdown of wnk usingen-Gal4 (en>wnk-IR106928) caused wing notches and loss of margin bristles (Fig 3B,E; a non-overlapping wnk dsRNA hairpin (supplementary Fig S1B online) driven by scalloped-Gal4 caused similar phenotypes; supplementary Fig S2C online). In addition, en>wnk-IR106928 resulted in reduction of the posterior compartment size with high penetrance (Fig 3B), an effect that was more pronounced when wnk-IR106928 was expressed throughout the whole wing blade using nubbin-GAL4 (Fig 3C). Size reduction was not due to apoptosis, as we did not detect an increase in Caspase-3 activation when Wnk function was compromised, nor to altered proliferation as assessed by anti-phospho-histone 3 staining (supplementary Fig S3 online) or to a reduction of dpp signalling (supplementary Fig S4G online). Size reduction is possibly a function of Wnk that is independent of Wnt signalling, as it is not dosage sensitive for Wnt pathway components, such as arr, arm, legless, axin, sgg (GSK3β) or pangolin (TCF; not shown).

Figure 3.

Loss of wnk leads to phenotypes reminiscent of a reduction of Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Proximal to the left and anterior up in A–G, anterior to the left in H–N. Compared with wild-type wings (A), knockdown of wnk using en>wnk-IR106928 (B) or nub>wnk-IR106928 (C) leads to a reduced wing size. Posterior compartments are in blue in A and B. (D–G) Compared with wild type (D), reduction of wnk by RNAi (E) or in unmarked clones in a Minute background of wnkex22 (F) and wnkMB06499 (G) leads to loss of wing margin structures (magenta arrowheads). (H–N) Confocal projections of third instar wing discs. Monochrome images show indicated single channels of the composite images. Sens is expressed in two stripes on either side of Wg. (H) Wild-type disc; (I) en>UAS-wnk-IR106928 disc: Sens is specifically lost in the posterior compartment (absence of Ci expressed anteriorly marks the posterior compartment). Compared with control clones (J), wnkex22 mutant clones (K; GFP negative; both in Minute background) show a reduction of Sens expression. Note that there is no effect on Wg expression. (L) Knockdown of fray also leads to a reduction of Sens expression. (M) dpp>dFz2 (marked by UAS-GFP) discs show an elevated level of Wg at the D/V border in dFz2 overexpression domain (M′) as well as expanded Sens (M″). (N) Co-expression of wnk-IR106928 with dFz2 in the dpp stripe markedly reduces Sens expression (compare N″ with M″), while not affecting Wg trapping (N′). Scale bars, 0.1 mm (A–G) and 50 μm (H–N).

Consistent with the RNAi data, homozygous mutant clones of wnkex22 and wnkMB06499 resulted in loss of wing margin and missing margin bristles (Fig 3F,G). Removing wnk function in the eye using ey-FLP led to a prominent, cell autonomous small rhabdomere phenotype (supplementary Fig S2D,F online), and occasional photoreceptor loss. Of note, no typical PCP phenotypes were detected in wings or eyes (Fig 3, supplementary Fig S2D–F). Also, both wnk alleles dominantly suppressed the sev-Dsh-induced photoreceptor loss phenotype, but not the PCP defects (Fig 2D,E, quantified in 2K).

In contrast to loss of wnk, co-expression of Wnk with dpp>dFz2 led to an increase in ectopic margin bristles compared with dFz2 alone (Fig 2I, quantified in 2L). Taken together with the LOF data, we conclude that Wnk regulates Wg signalling and is sufficient to further stimulate activated Wg signalling.

Wnk regulates peak canonical signalling in the wing

Notch signalling activates wg expression at the wing margin [2]. We did not detect an effect on a Notch reporter in wing discs (supplementary Fig S4B online) nor was Wg expression changed by RNAi-mediated knockdown of wnk or in homozygous mutant clones (Fig 3H–K), excluding an indirect effect on Wg signalling through Notch. In en>wnk-IR106928 wing discs, expression of the high threshold, direct Wg-target Sens was reduced or lost in the posterior compartment (Fig 3I). Similarly, Sens expression was frequently lost cell autonomously in wnkex22 and wnkMB06499 clones (Fig 3K). Neither wnk LOF background affected the low threshold target Dll (supplementary Fig S4C,D online and not shown).

Overexpression of dFz2 increases canonical Wg signalling and results in trapping of Wg on the surface of the dFz2-overexpressing cells [18]. Accordingly, dpp>dFz2 causes accumulation of Wg near the D–V border and causes expansion and increase of Sens expression (Fig 3M) concomitant with ectopic margin bristles in adult wings (Fig 2G). When dFz2 was overexpressed and Wnk was simultaneously knocked down by RNAi, we still observed accumulation of Wg, as in dFz2 overexpression alone (Fig 3N’), but Sens was dramatically reduced (Fig 3N’’).

We generated wnk LOF MARCM clones in which GSK3β was knocked down using RNAi or that express stable β-catenin/Armadillo (ArmS10), both causing constitutive activation of the pathway at the level of or downstream of the destruction complex [2]. Removing Wnk activity using either wnkex22 or wnkMB06499 alleles did not affect these ectopic signalling/overactivation phenotypes, that is, overgrowth of tissue in the clones (compare supplementary Fig S4E,F online for GSK3β knock-down-induced overgrowth).

Our data thus indicate that Wnk is required for peak levels of canonical Wg signalling downstream of Wg, but upstream of the degradation complex.

A possible mechanism of Wnk regulation of Wnt signalling

We tested the ability of a catalytically active fragment of Wnk (S434E; the kinase-dead isoform of Wnk, D420A, served as a control) to phosphorylate Wnt pathway components in vitro. Constitutively, active Wnk was able to phosphorylate itself (Fig 1E) [19], but neither Dsh fragments nor the C-termini of the Wnt (co)-receptors Fz, dFz2 or Arr were phosphorylated by GST-Wnk-NT in vitro (Fig 1E). Recently, the prorenin receptor PRR/ATP6AP2, a component of the vacuolar H+ ATPase was shown to be required for Wnt signalling [20]. Although, Arabidopis thaliana WNK8 phosphorylates the C-subunit of the vacuolar H+ ATPase subunit (Vha44) [21], Wnk was not able to phosphorylate the Drosophila homologue of Vha44 (Fig 1E).

In mammals, Wnks phosphorylate SPAK and OSR1 (STE20/SPS1-related proline–alanine-rich kinase and oxidative stress-responsive protein type 1) kinases during ion channel regulation [12, 22]. Constitutively active, but not kinase dead, Wnk was able to phosphorylate catalytically inactive Fray kinase, the Drosophila homologue of OSR1/SPAK (FrayD185A; Fig 1E; catalytically inactive Fray was used as substrate, as OSR/SPAK kinases are able to autophosphorylate). While we did not find an effect of fray knockdown in Dsh gel-shift assays in S2 cells or on the ectopic margin bristle phenotype induced by dpp>dFz2 (Fig 2M), knockdown of fray by en>frayIR106919 led to a reduction of Sens expression in wing discs and to wing margin defects (Figs 2J), suggesting that Wnk might act through its downstream kinase target Fray [16].

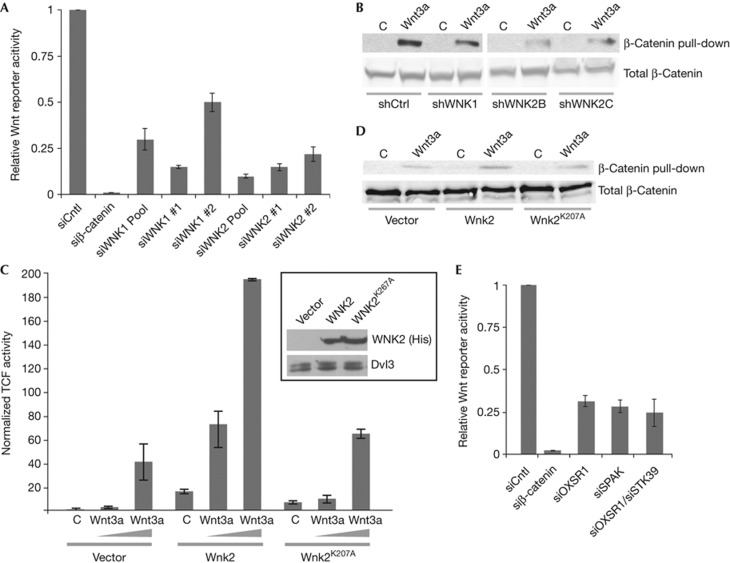

Human WNK1/2 modulate canonical Wnt signalling

On the basis of the Drosophila data, we hypothesized that Wnk function in Wnt/β-catenin signalling might be conserved in mammals. Indeed, siRNA-mediated knockdown of WNK1 and WNK2, the WNKs expressed in HEK293T cells, significantly reduced the expression of the Wnt-signalling reporter (Fig 4A; see supplementary Fig S5A online for knockdown efficiencies of siRNAs). Consistently, knockdown of WNK1 and WNK2 through shRNAs also reduced the amount of stabilized, uncomplexed β-catenin pulled down from lysates of HEK293T cells (Fig 4B; note that these shRNAs also reduce Wnt reporter activity, supplementary Fig S5D online). Knockdown of WNK1 and WNK2 had no effect on cell viability, nor, consistent with in vivo Drosophila data, did it affect Notch signalling (supplementary Fig S5B,C online).

Figure 4.

Human WNK1 and WNK2 modulate canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling. (A) Reporter assays show that knockdown of WNK1 or WNK2 siRNAs leads to a significant reduction of the Wnt3a-induced reporter activity in HEK293T cells (n⩾3 in all cases; error bars are s.d.; T-test; P<0.001). siRNA against β-catenin was used as control. (B) Uncomplexed β-catenin from HEK293T cells transduced with indicated shRNAs and treated with control or Wnt3a-conditioned medium was pulled down with GST-E-cadherin. Compared with control, knockdown of WNK1 and WNK2 reduces free β-catenin. Lower panels: total β-catenin. (C) Overexpression of WNK2 but not kinase-dead WNK2K207A potentiates Wnt3a. Inset shows expression levels of His-WNK2, compared with endogenous Dvl3 as loading control. n=3; error bars are s.d. (D) Uncomplexed β-catenin levels were specifically increased by WNK2, but not by WNK2K207A overexpression. (E) siRNA-mediated knockdown of OSR1 and SPAK (either alone or in combination) significantly reduces Wnt3a-induced reporter activity in HEK293T cells. n=3; error bars are s.d.

Transfection of WNK2 in 293T cells stimulated Wnt3a activation of TOPFlash in a dose and kinase activity-dependent manner (Fig 4C), and potentiation of Wnt signalling by WNK2 overexpression resulted in an increase of free cytoplasmic β-catenin (Fig 4D). As for Sens expression in wings, WNKs probably act through the downstream kinases OSR1/SPAK, as their knockdown also reduced Wnt reporter activity in HEK293T cells (Fig 4E). In conclusion, in Drosophila and in human cells, Wnk kinases act upstream of β-catenin, are required for peak Wnt signalling levels and, when overexpressed, can potentiate canonical Wnt signalling in a manner that involves their downstream kinases OSR1/SPAK/Fray.

Discussion

Wnk kinases are known to control ion homoeostasis in the distal nephron of the kidney and in the brain by regulating the activity of Na/K/Cl co-transporters, and misregulation of WNK1/4 causes Gordon syndrome characterized by hyperkalemia and hypertension [12, 14]. Here, we show that Wnks have a new, unexpected and conserved role in the regulation of Wnt signalling in vivo in flies and in human cell culture.

Consistent with a reduction of Dsh phosphorylation levels, Wnk in Drosophila S2 cells (M. Boutros, unpublished observation) and human WNK2/4 kinases in A375 melanoma cells [23], respectively, were also identified as candidate-positive regulators of Wnt/β-catenin signalling. In contrast, WNK1 in A375 cells [23] and Wnk in Drosophila Clone-8 cells had antagonistic effects [23, 24]. Although Wnk might have cell-type-dependent functions that lead to different effects on Wnt signalling, our functional in vivo analyses and genetic interactions between wnk and dfz2 and dsh indicate that Wnk acts positively in Wg signalling in vivo. Also, the direct Wg-target Sens at the D/V boundary requires a high concentration of Wg signalling [25], and loss of wnk causes autonomous loss of Sens expression. We detect no effect of loss of wnk on Dll expression, a target that requires lower levels of Wnt activity [26], consistent with a lack of an absolute requirement for Wnk in Wnt signalling. Indeed, knockdown of WNK1/2 reduces the activity of transcriptional Wnt reporters in HEK293T cells and WNK2 kinase activity is required for its stimulatory effect.

Most Wnk kinase studies have focused on their role in the regulation of ion homoeostasis in the kidney and little is known about the function(s) of Wnks in development. WNK1 knockout mice die by E12 with cardiac and angiogenesis defects [27]. Nevertheless, there is emerging evidence that WNKs might have essential roles in other signalling pathways. For example, WNK1/4 can phosphorylate Smads and affect BMP signalling in culture [28].

Both genetic in vivo data and β-catenin stability assays in human cell culture argue that Wnk kinases act upstream of β-catenin stabilization, but downstream of ligands in Wnt signalling. Nevertheless, Wnk fails to directly phosphorylate the intracellular parts of the Fz and Lrp5/6-Arr co-receptors as well as Dsh itself. While Wnks are able to directly phosphorylate and have effects on subcellular localization and transport of the NKCC and KCC co-transporters (reviewed in [12, 14]), their regulatory effects on ion uptake are mediated through activation/phosphorylation of the OSR1 and SPAK kinases [22]. Consistently, Wnk also phosphorylates Fray, the Drosophila SPAK/OSR1 homologue, in vitro (Fig 1E) [16], and knockdown of fray in Drosophila in vivo and OSR1 and SPAK in human cell culture reduces canonical Wnt signalling, suggesting Fray/OSR1/SPAK might mediate the Wnk effect on Wnt signalling that is conserved between flies and humans.

Methods

Detailed methods can be found in the supplementary information online.

Dsh phosphorylation band-shift assay. Dsh band-shift assays were done as described [13] and signals of fluorescent secondary antibodies were quantified on a Li-Cor Odyssey. Phosphorylated Dsh (that is, shifted Dsh) was quantified as a percentage of total Dsh.

Wnt reporter gene and soluble β-catenin assays. Wnt reporter assay was performed in 384-well assay plates (Greigner Bio). 4000 HEK293T cells were reverse transfected with indicated siRNAs using RNAiMax transfection reagent (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 12.5 nM. After 24 h of incubation, cells were further transfected with the following plasmids using Trans-IT transfection reagent (Mirus): 5 ng of β-catenin/TCF-LEF-responsive Firefly luciferase (FL) reporter along with 40 ng of constitutively active β-actin promoter-driven Renilla luciferase (RL) for normalization. To activate the pathway, WNT3a-conditioned medium was added 24 h after plasmid transfection. After a total of 72 h of incubation, FL and RL activities were measured in a luminometer (Mithras LB940), and FL/RL ratio was calculated for each well. All sample ratios were normalized to control siRNA-transfected cells, and relative fold values were calculatedThe TCF/LEF luciferase assay was performed by co-transfection of the Super8XTOPFlash reporter and the pBind vector (Promega), which contains the Renilla luciferase gene driven by the SV40 early enhancer/promoter, together with the indicated plasmids. Two days after transfection, cells were treated overnight with control or Wnt3a CM and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega)293T cells were infected with shCtrl, shWnk1 or shWnk2 lentiviruses. Uncomplexed β-catenin was measured as previously described [29]. Target sequences for Wnk siRNAs and shRNAs can be found on supplementary Table S1 online.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to H. Bellen, S. Cohen, C. Plass, C. Schmidt, A. Fischer, Vienna Drosophia NAi Center and Bloomington for reagents. We thank the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Microscopy Shared Resource Facility and A. Guernet for technical support, and for plasmids, and are grateful to F. Marlow for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by an American Heart Association grant 13GRNT14680002 (to A.J.) and National Institute of Health grants GM088202 (to A.J.), EY13256 (to M.M.) and HD66319 (to S.A. and M.M.). L.G. was supported by a Chair of Excellence program from INSERM and the University of Rouen. M. Boutros is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the European Commission (‘MC-EXT Cellular Signaling’ and ‘CancerPathways’).

Author contributions: E.S., H.B., M.M. and A.J. designed most experiments, analysed and interpreted data. L.G., S.A., K.D., and M. Boutros conceived and performed additional experiments. S.B. and M. Bodak helped with experiments, and E.S., M.M. and A.J. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Clevers H, Nusse R (2012) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149: 1192–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup S, Verheyen EM (2012) Wnt/Wingless signaling in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 4: piia007930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maung SM, Jenny A (2011) Planar cell polarity in Drosophila. Organogenesis 7: 165–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrimon N, Mahowald AP (1987) Multiple functions of segment polarity genes in Drosophila. Dev Biol 119: 587–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi H, Sese S, Lee JS, Shirakawa T, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, Yanagawa S (2004) Biochemical characterization of the Drosophila wingless signaling pathway based on RNA interference. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2012–2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penton A, Wodarz A, Nusse R (2002) A mutational analysis of dishevelled in Drosophila defines novel domains in the dishevelled protein as well as novel suppressing alleles of axin. Genetics 161: 747–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Price MA, Strutt D (2006) Planar polarity is positively regulated by casein kinase Iepsilon in Drosophila. Curr Biol 16: 1329–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanfeng WA, Berhane H, Mola M, Singh J, Jenny A, Mlodzik M (2011) Functional dissection of phosphorylation of Disheveled in Drosophila. Dev Biol 360: 132–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod JD (2001) Unipolar membrane association of Dishevelled mediates Frizzled planar cell polarity signaling. Genes Dev 15: 1182–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong F, Schweizer L, Varmus H (2004) Casein kinase Iepsilon modulates the signaling specificities of dishevelled. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2000–2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K, Brink M, Wodarz A, Varmus H, Nusse R (1997) Casein kinase 2 associates with and phosphorylates dishevelled. EMBO J 16: 3089–3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick JA, Ellison DH (2011) The WNKs: atypical protein kinases with pleiotropic actions. Physiol Rev 91: 177–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein TJ, Jenny A, Djiane A, Mlodzik M (2006) CKIepsilon/discs overgrown promotes both Wnt-Fz/beta-catenin and Fz/PCP signaling in Drosophila. Curr Biol 16: 1337–1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle KT, Rinehart J, Lifton RP (2010) Phosphoregulation of the Na-K-2Cl and K-Cl cotransporters by the WNK kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802: 1150–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J, Senti KA, Senti G, Newsome TP, Asling B, Dickson BJ, Suzuki T (2008) Systematic identification of genes that regulate neuronal wiring in the Drosophila visual system. PLoS Genet 4: e1000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Shibuya H (2013) WNK signaling is involved in neural development via Lhx8/Awh expression. PLoS One 8: e55301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couso JP, Bishop SA, Martinez Arias A (1994) The wingless signalling pathway and the patterning of the wing margin in Drosophila. Development 120: 621–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeg GH, Selva EM, Goodman RM, Dasgupta R, Perrimon N (2004) The Wingless morphogen gradient is established by the cooperative action of Frizzled and Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan receptors. Dev Biol 276: 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, English JM, Wilsbacher JL, Stippec S, Goldsmith EJ, Cobb MH (2000) WNK1, a novel mammalian serine/threonine protein kinase lacking the catalytic lysine in subdomain II. J Biol Chem 275: 16795–16801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen G (2011) Renin, (pro)renin and receptor: an update. Clin Sci (Lond) 120: 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong-Hermesdorf A, Brux A, Gruber A, Gruber G, Schumacher K (2006) A WNK kinase binds and phosphorylates V-ATPase subunit C. FEBS Lett 580: 932–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thastrup JO, Rafiqi FH, Vitari AC, Pozo-Guisado E, Deak M, Mehellou Y, Alessi DR (2011) SPAK/OSR1 regulate NKCC1 and WNK activity: analysis of WNK isoform interactions and activation by T-loop trans-autophosphorylation. Biochem J 441: 325–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biechele TL et al. (2012) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and AXIN1 regulate apoptosis triggered by inhibition of the mutant kinase BRAFV600E in human melanoma. Sci Signal 5: ra3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R, Kaykas A, Moon RT, Perrimon N (2005) Functional genomic analysis of the Wnt-wingless signaling pathway. Science 308: 826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolo R, Abbott LA, Bellen HJ (2000) Senseless, a Zn finger transcription factor, is necessary and sufficient for sensory organ development in Drosophila. Cell 102: 349–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CJ, Cohen SM (1997) Long-range action of Wingless organizes the dorsal-ventral axis of the Drosophila wing. Development 124: 871–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Wu T, Xu K, Huang IK, Cleaver O, Huang CL (2009) Endothelial-specific expression of WNK1 kinase is essential for angiogenesis and heart development in mice. Am J Pathol 175: 1315–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Chen W, Stippec S, Cobb MH (2007) Biological cross-talk between WNK1 and the transforming growth factor beta-Smad signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 282: 17985–17996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Bafico A, Harris VK, Aaronson SA (2003) A novel mechanism for Wnt activation of canonical signaling through the LRP6 receptor. Mol Cell Biol 23: 5825–5835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.