Abstract

Symptomatic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection complicated by acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) in a toddler is rare. Our patient is a 14 month-old boy who presented with listlessness and reduced eye movements nearly 10 days after a prodromal upper respiratory illness that was accompanied by an amoxicillin rash. On examination, the boy appeared drowsy, had a congested throat and a resolving lower extremity rash, but otherwise had a normal neurological examination. Investigation revealed lymphocytosis, mildly elevated liver enzyme and a positive EBV IgM serology. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed pleocytosis. Subsequent brain and spine MRI showed demyelinating disease extending from the cerebral peduncles, across the brain stem and down to the mid-thoracic spinal cord. The patient was treated as a case of ADEM and given intravenous methylprednisolone. On outpatient follow-up his symptoms resolved completely in 6 weeks.

Background

This is a rare case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) as it occurred subsequent to a symptomatic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in a 14 month-old boy. Symptomatic infectious mononucleosis (IM) is not a common occurrence in a child of this age group and ADEM is a rare presentation at this age. To our knowledge, no case of ADEM following IM in a child of this age group has been reported.

Case presentation

A 14 month-old boy was admitted to the paediatric unit with vomiting, listlessness and abnormal eye movements. This was preceded, 10 days ago, by an upper respiratory tract (URT) illness, which was characterised by fever, dry cough and ‘swollen neck’. With the onset of this prodromal URT illness, the patient was given Augmentin by the primary physician.

Three days after Augmentin was started, he developed a diffuse maculopapular rash involving the face, trunk and limbs (in no particular order). This had been the first time he developed a rash following medications although he did receive amoxicillin in the past. Medical attention was sought in the country of stay and this rash was treated as an allergic reaction.

The boy's URT symptoms subsided and his rash was resolving within the first 10 days. He subsequently developed the neurologic symptoms and was admitted to the unit.

His medical history was essentially unremarkable and was up to date on his vaccination schedule.

On examination the boy was afebrile, but appeared drowsy, had a congested throat and a resolving lower extremity rash. Otherwise, there were no neurological deficits and examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

Biochemical and haematological investigations were normal except for mild leucocytosis of 17.4×103/mm3. Liver function tests showed mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase enzyme (ALT) level of 53 U/L (upper limit of normal 36 U/L).

Infectious workup including blood cultures was negative, but immunological workup revealed positive IgM for EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA). IgG for EBV VCA and IgG for EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) were both negative. On another note, cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgM was also positive.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was remarkable for pleocytosis of 40 white cell count/mm3 with lymphocytic predominance (93% lymphocytes), but revealed normal protein (0.35 g/L) and glucose (3.5 mmol/L) concentrations. No organisms were seen and bacterial cultures were negative. A CSF PCR assay for EBV was negative, and so was the PCR assay for CMV, adenovirus, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1), herpes simplex virus (HSV2), Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), enterovirus (EV) and mumps virus (MV). EBV specific immunoglobulin was not tested for in the CSF.

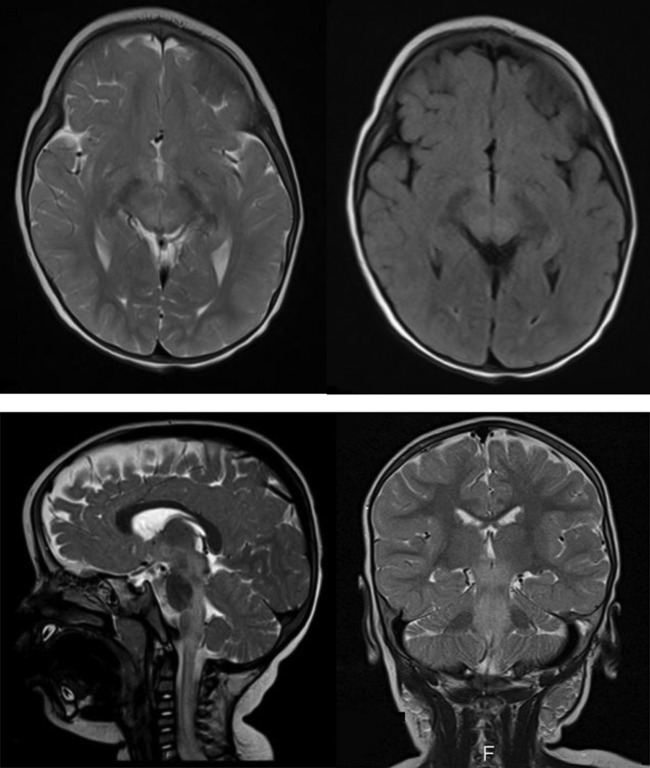

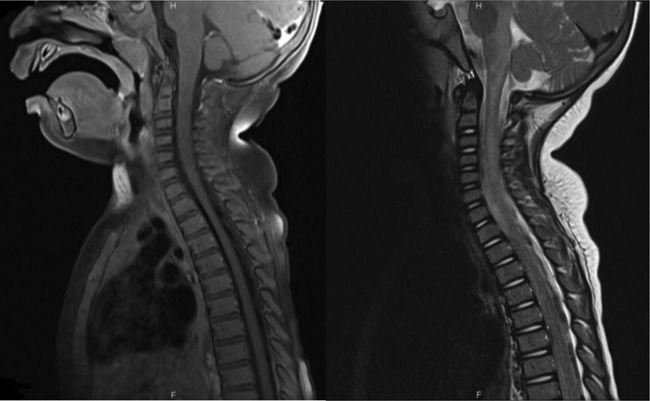

A non-contrast CT examination of the brain showed no appreciable parenechymal abnormality while brain and spine MRI showed an extensive demyelinating lesion with significant involvement extending from the cerebral peduncles, across the brain stem and down to the mid-thoracic spinal cord which lacked enhancement in the postcontrast series (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Brain MRI. (A) axial T2, (B) axial FLAIR, (C) sagittal T2 and (D) coronal T2. MRI in multiple plains using different pulse sequences showing diffuse increase in signal intensity in the cerebral peduncles, midbrain, around the fourth ventricle and the cervicomedullary junction down to the mid-cervical region.

Figure 2.

Spinal cord MRI. (A), sagittal T2 and (B), sagittal T1 postcontrast. Sagittal MRI in T2 and postcontrast T1 WI showing diffuse patchy intramedullary areas of increased signal intensity along the cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord with no significant postcontrast enhancement.

A brain biopsy was not performed. Although histopathology by itself offers the highest diagnostic certainty, the combination of clinical features and MRI findings together can theoretically offer an equally high diagnostic certainty.1 Brain biopsy was considered an invasive and unnecessary procedure in this case with a risk of short and long-term complications.

Differential diagnosis

ADEM presents with a constellation of non-specific neurological symptoms and signs that makes it difficult to differentiate from acute encephalitis/myelitis. Even radiological findings can overlap, for instance when it comes to differentiating multiphasic ADEM from multiple sclerosis (MS) or a focal ADEM lesion from tumour-like lesions. The subtle differences in presentation and workup results create a diagnostic challenge to neurologists and neuroradiologists.2

In any patient presenting with what appears to be acute encephalopathy based on history and physical examination, the first priority is to rule out an acute bacterial or viral infection of central nervous system (CNS) such as meningitis or encephalitis. There was no evidence of bacterial or viral CNS infection in our case. Pleocytosis, predominantly lymphocytic, was the only noted abnormality.

ADEM is an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder of the CNS as opposed to a primary CNS infection. It is, however, commonly preceded by an infection and less commonly preceded by vaccination.2

Treatment

Pulse steroid therapy was initiated with 30 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone intravenously for the 5 days of his hospitalisation.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was scheduled for an outpatient follow-up appointment 2 weeks after his hospital discharge. He was found to be asymptomatic and showed clinical improvement with no signs of neurological impairment. The clinical picture, in combination with the MRI findings and the response to treatment, strongly supports the diagnosis of ADEM. A repeat brain and spine MRI was suggested to the family as it would help rule out MS and establish ADEM as the most likely diagnosis. The patient's family, however, continued to have no problems and declined the repeat MRI as they had concerns about general anaesthesia.

Discussion

Definition and epidemiology

ADEM is a monophasic, inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS seen predominantly in children. Reported annual incidences of this disease in developed countries have ranged from 0.07 to 0.8/100 000 with the average age of onset between 6 and 8 years. However, the disease is much less common in children below 2 years of age.2 3–7

Differentiating ADEM from encephalitis/myelitis and other childhood demyelinating diseases poses a diagnostic dilemma. In order to solve this issue, efforts were directed towards developing a standardised case definition clearly outlining the diagnostic features of different demyelinating diseases of childhood. Standardised definitions are necessary not only in the clinical setting, but for widespread use in surveillance and research (clinical trials).

Fairly recently, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society organised an international paediatric MS study group (Study Group) to set diagnostic criteria.8 Similarly, standard criteria were developed by the Brighton Collaboration Encephalitis Working Group around the same time in an effort to improve comparability of vaccine safety data.1

Within the definition proposed by the Study Group, the diagnosis of ADEM requires a first clinical event, acute or subacute in nature, of both polysymptomatic encephalopathy and focal or multifocal involvement predominantly affecting the CNS white matter. The requisite inclusion of encephalopathy, although overly restrictive, was performed to increase diagnostic specificity and helps differentiate ADEM from MS. A number of other clinical features, laboratory test findings and MRI findings also serve as diagnostic criteria.2 8

While a viral infection often precedes ADEM, documentation of an antecedent infection and isolation of an infectious agent are not requirements for diagnosis.8

Clinical presentation and aetiology

The classic presentation involves multifocal neurological deficits. However, impaired level of consciousness (drowsiness, lethargy, stupor or coma) is a key feature.3 At least 70% of patients report an antecedent prodromal event 2–30 days prior to the onset of ADEM symptoms.3

ADEM is usually triggered by systemic viral infections. Viruses that have been implicated in studies or case reports to cause ADEM include coronavirus, coxsackie, CMV, EBV, HSV, influenza, measles, rubella, VZV and West Nile virus.2–3

While measles was identified as a major cause of ADEM in the past, the incidence and prevalence of encephalomyelitis has significantly decreased in areas where children are vaccinated against measles.9 Meanwhile, non-specific respiratory viral infections have now become the major prodromal illness in developed countries. The infection typically occurs days to weeks prior to the disease.3

In most cases of ADEM, however, the aetiologic agent remains unknown with only the occasional microbiological or serological evidence of a viral agent. A 6 year retrospective study by Murthy et al published in 2002 identified 18 patients with ADEM, with 13 who had initially presented with a prodromal URT illness. Despite rigorous testing, a definite microbiological diagnosis was established in only one child and the result was EBV.10

IM and pathogenesis of EBV-related CNS complications

Although EBV, and even CMV infections are established causes of acute viral encephalitis,11 they have only been identified in case reports as causes of ADEM.12–18 Moreover, only a few of the cases reported the occurrence of a symptomatic EBV infection rather than just serological or CSF evidence of EBV. Bahadori et al12 reported a case of ADEM following IM in a 17-year-old girl, an age where IM is the most common. Given ADEM's lower incidence in very young children (<2 years), and that its occurrence after a symptomatic EBV infection in a toddler has not been reported, we reported the case of a 14 month-old boy who developed ADEM 10 days after having a prodromal illness that is clinically compatible with IM.

The diagnosis of IM is a clinical one. Although the usual constellation of symptoms was present in this case, it is usually non-specific. However, the phenomenon most consistent with EBV infection was the development of a diffuse maculopapular rash a few days after the administration of Augmentin. Studies have found the relative risk of developing this characteristic rash to be as high as 58 times in EBV-positive patients as opposed to those without EBV.19 A monospot test, which is normally sensitive and specific for EBV mononucleosis, is of limited value in children <4 years17 and so was not performed in this case. The clinical picture, along with the lymphocytosis, IgM seropositivity to EBV VCA and lymphocytic pleocytosis, are sufficient to establish EBV infection as the culprit behind this boy's ADEM. Another remarkable laboratory finding is the mild elevation in liver enzymes which can be seen with IM.

According to a case-control study of 44 children by Selter et al, serum IgG antibodies to EBNA-1 were elevated in 42% of children, which was no more than in healthy controls (43%). It was in fact the IgM to EBV early antigen (EA) that was seen in 16% (3 cases) of only ADEM cases. This is worth noting as the finding is compatible with the serology profile of our patient.20 Associations have also been detected between EBV seropositivity and MS in adults and children.21 22

CNS complications of EBV infection occur in up to 18% of patients with IM.23 To date, many attempts have been made to explain the pathogenesis of EBV-related encephalitis and autoimmune demyelinating diseases, such as ADEM. Weinberg et al studied the CSF patterns in different EBV-related neurological diseases. They explained direct infection of neurons and glial cells and lytic EBV replication as the likely pathogenesis of EBV encephalitis, where there is intense viral replication and vigorous inflammation. On the other hand, postinfectious complications were associated with low viral replication and vigorous inflammation.23

For ADEM, cross-reactivity between EBV and myelin proteins has been proposed as a potential mechanism by which the autoimmune response is triggered.1 2 This is the phenomenon known as molecular mimicry which can lead to a distant autoimmune reaction and does not necessarily require the viral agent to actively replicate in the CNS.

Other mechanisms were proposed by which viruses such as EBV could lead to ADEM. One thought is that if and when the virus directly infects the surrounding myelin-supporting cells, it inserts specific polypeptides into host cell membranes, which in turn initiates an autoimmune response causing demyelination. Alternatively, the virus infecting the myelin-supporting cells could elicit the release of sequestered myelin antigens into the circulation and trigger autoimmunity.1 24 This matter of pathogenesis remains a subject of extensive research.

Relevance of CMV-IgM seropositivity

CMV is a prevalent pathogen, and up to 20% of children in the USA would have contracted CMV before puberty. Primary CMV infection is commonly inapparent. When it is symptomatic, it will only cause up to 7% of cases of mononucleosis, manifesting with symptoms identical to those caused by EBV.25 In the laboratory evaluation of acute mononucleosis syndrome, lymphocytosis with a positive EBV IgM is sufficient to establish EBV as the culprit over CMV (regardless of CMV immunoglobulin seropositivity).25 Instances of EBV and CMV coinfection, although rare, could still occur.26 Whether EBV, CMV or a combination of both contributed to this boy's ADEM cannot be determined for sure. However, an EBV mononucleosis syndrome followed by ADEM would be the most likely explanation.

Radiological findings in ADEM

In our patient, a brain and spine MRI supported the diagnosis of ADEM by showing characteristic diffuse demyelinating disease (figures 1 and 2).

MRI is the preferred modality for imaging the brain in patients with ADEM since early CT imaging is often normal, as seen in this case. T2-weighted imaging is the preferred sequence to show the hyperintense signals in the involved parenchymal region. The lesions normally do not show enhancement in the contrast-enhanced images, and typically do not show restricted diffusion in the diffusion-weighted images either.

Finally, it is essential to screen the whole neural axis including the brain and the spinal cord to show the complete extension of the pathological process.

Treatment, outcome and prognosis

Owing to lack of randomised controlled trials on treatment of ADEM, there is no standard therapy for ADEM. Instead, it is treated similar to MS and other autoimmune diseases. Based on the clinician's expertise and data from small series, different immunosuppressive approaches are pursued for different cases of ADEM and these include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasmapheresis.2 3

Most paediatric groups described the use of high-dose steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone (10–30 mg/kg/day up to a maximum dose of 1 g/day) or dexamethasone (1 mg/kg) for 3–5 days) followed by oral steroid taper for 4–6 weeks. Based on their experience, full recovery was reported in 50–80% of patients.2

ADEM has an overall good prognosis and most patients recover, particularly the paediatric population. Based on collective data from case series, approximately two-thirds of patients make a complete recovery.2 10 27 Mortality from ADEM in the paediatric population has been reported at rates from 0% to less than 5% in more recent studies. However, permanent cognitive and neurological deficits could be seen in 10–30% of patients.3 10 Close neurological follow-up is thus warranted.

Learning points.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a monophasic, inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) seen predominantly in children and is normally preceded by non-specific, systemic viral infections.

Symptomatic Epstien–Barr virus (EBV) infection in a child younger than 2 years of age is uncommon. The occurrence of ADEM following a symptomatic EBV infection in this age group is a rare case in paediatric neurology.

Cross-reactivity between EBV and myelin proteins has been proposed as a potential mechanism by which EBV could elicit an autoimmune response targeting the central nervous system.

ADEM has an overall good prognosis in the paediatric population.

Footnotes

Contributors: HM was involved in writing the manuscript, obtaining departmental approval for case write-up and the patient's care. GAZ involved in writing the manuscript, obtaining departmental approval for case write-up and the patient's care. AE was involved in interpreting radiological findings, selecting MRI figures and writing the manuscript. KM was involved in the care of the patient and principal investigator supervising and reviewing case write-up.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sejvar JJ, Kohl KS, Bilynsky R, et al. Encephalitis, myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM): case definitions and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine 2007;2013:5771–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenembaum S, Chitnis T, Ness J, et al. International Pediatric MS Study Group. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurology 2007;2013(16 Suppl 2):S23–36 Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyle PK. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Clinical neuroimmunology. Curr Clin Neurol 2011;2013:203–17 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leake JA, Albani S, Kao AS, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in childhood: epidemiologic, clinical and laboratory features. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;2013:756–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banwell B, Kennedy J, Sadovnick D, et al. Incidence of acquired demyelination of the CNS in Canadian children. Neurology 2009;2013:232–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pohl D, Hennemuth I, Von Kries R, et al. Paediatric multiple sclerosis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in Germany: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Pediatr 2007;2013:405–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visudtibhan A, Tuntiyathorn L, Vaewpanich J, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a 10-year cohort study in Thai children. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2010;2013:513–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krupp LB, Banwell B, Tenembaum S. Consensus definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related disorders. Neurology 2007;2013(16, Supplement 2):S7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RT, Griffin DE, Gendelman HE. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis. Semin Neurol 1985;2013:180–90 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy SN, Faden HS, Cohen ME, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. Pediatrics 2002;2013(2 Pt 1):e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung KL, Liao HT, Tsai ML. Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis in children. Acta Paediatr Taiwan 2000;2013:140–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahadori HR, Williams VC, Turner RP, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following infectious mononucleosis. J Child Neurol 2007;2013:324–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Çiftçi E, İnce E, Tuğba B, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with epstein-barr virus infection. Journal of Ankara Medical School 2003;25:149–54 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revel-Vilk S, Hurvitz H, Klar A, et al. Recurrent acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with acute cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Child Neurol 2000;2013:421–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaguri R, Shelef I, Ifergan G, et al. Fatal acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with cytomegalovirus infection. BMJ Case Rep. Published online: 17 Mar 2009. doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanzaki A, Yabuki S. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) associated with cytomegalovirus infection—a case report. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 1994;2013:511–13 (in Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sumaya CV, Ench Y. Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis in children. II. Heterophil antibody and viral-specific responses. Pediatrics 1985;2013:1011–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menge T, Hemmer B, Nessler S, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: an update. Arch Neurol 2005;2013:1673–80 Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Linden PD, Van der Lei J, Vlug AE, et al. Skin reactions to antibacterial agents in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;2013:703–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selter RC, Brilot F, Grummel V, et al. Antibody responses to EBV and native MOG in pediatric inflammatory demyelinating CNS diseases. Neurology 2010;2013:1711–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banwell B, Krupp L, Kennedy J, et al. Clinical features and viral serologies in children with multiple sclerosis: a multinational observational study. Lancet Neurol 2007;2013:773–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ascherio A, Munch M. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Epidemiology 2000;2013:220–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberg A, Li S, Palmer M, et al. Quantitative CSF PCR in Epstein-Barr virus infections of the central nervous system. Ann Neurol 2002;2013:543–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller SD, McRae BL, Vanderlugt CL, et al. Evolution of the T-cell repertoire during the course of experimental immune-mediated demyelinating diseases. Immunol Rev 1995;2013:225–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor GH. Cytomegalovirus. Am Fam Physician 2003;2013:519–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson D, Huntington MK. Co-infection with cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus in mononucleosis: case report and review of literature. S D Med 2009;2013:349, 351–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Idrissova Z, Boldyreva MN, Dekonenko EP, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: clinical features and HLA-DR linkage. Eur J Neurol 2003;2013:537–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]