Abstract

Oncolytic viruses obliterate tumor cells in tissue culture but not against the same tumors in vivo. We report that macrophages can induce a powerfully protective antiviral state in ovarian and breast tumors, rendering them resistant to oncolytic virotherapy. These tumors have activated JAK/STAT pathways and expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) is upregulated. Gene expression profiling (GEP) of human primary ovarian and breast tumors confirmed constitutive activation of ISGs. The tumors were heavily infiltrated with CD68+ macrophages. Exposure of OV-susceptible tumor cell lines to conditioned media from RAW264.7 or primary macrophages activated antiviral ISGs, JAK/STAT signaling and an antiviral state. Anti-IFN antibodies and shRNA knockdown studies show that this effect is mediated by an extremely low concentration of macrophage-derived IFNβ. JAK inhibitors reversed the macrophage-induced antiviral state. This study points to a new role for tumor-associated macrophages in the induction of a constitutive antiviral state that shields tumors from viral attack.

Replication-competent viruses from diverse families are being developed as novel therapeutics for cancer therapy1,2. The oncolytic viruses are either engineered or evolved for selective infection and/or amplification in cancer cells3,4,5. Viral amplification through the release of progeny, intercellular fusion between infected and uninfected cells or combination with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy significantly increases the bystander killing by this class of therapeutics6,7. The goal is to achieve rapid intratumoral viral spread to significantly debulk the tumor, together with induction of immune mediated clearance of residual tumor cells or distant tumor nodules8,9. Potent antitumor immunity that is subsequently established has been shown to protect the animal from further tumor challenge9,10.

Numerous oncolytic virotherapy clinical trials are ongoing using RNA (measles, vesicular stomatitis, retrovirus, poliovirus, coxsackie) and DNA viruses (adenovirus, herpes simplex, vaccinia), including a phase IIb trial in hepatocellular carcinoma with JX-594 vaccinia virus expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF)11. A Phase III trial using OncoVEX a herpes simplex virus expressing GM-CSF (Talimogene laherparepvec) in melanoma is completed and results are pending1. Preclinical and clinical data using OncoVEX and other viruses point to the host cellular immune response playing an important role in the antitumor activity12,13.

However, oncolytic virotherapy has been less curative in other tumor models and human trials. Complete regression of large syngeneic plasmacytomas in immunocomptent animals with a single dose of oncolytic VSV-mIFN-NIS demonstrating the virotherapy paradigm was recently reported14. But more often than not, response has been less spectacular and virus infection and spread can be restricted by host innate or adaptive immune responses, for example, infiltrating immune cells that eliminate virally infected cells, restricting virus spread and overall replication15,16. Pre-conditioning of host with cyclophosphamide before virus administration can help to increase overall viral titer in tumors as well as suppress induction of primary antiviral antibodies and the anamnestic response16,17,18. Viral spread can also be shut down due to destruction of vascular structures by VSV replication within the tumor mass, initiating an inflammatory reaction including a neutrophil-dependent initiation of microclots within tumor blood vessels19. Physical barriers imposed by tumor architecture can hinder progeny spread to other tumor nests within the stroma20. Suboptimal vascular perfusion in poorly vascularized tumors also reduces virus delivery and therapeutic outcome.

The tumor microenvironment can profoundly alter tumor cell susceptibility to chemotherapy but the impact of the microenvironment on oncolytic virotherapy has not previously been reported21. Here we show that a major limitation to oncolytic virotherapy is constitutive activation of ISGs and induction of an antiviral state in tumor cells by associated stromal cells, rendering permissive cancer cells to a non-permissive virus resistant state in vivo. Conventional virus infection assays are typically performed in vitro in the absence of any accessory cells of the tumor microenvironment; these results often show that tumor cells are generally permissive and support high levels of viral replication. As such, it is often assumed that cancer cells have dysregulated antiviral response pathways that are inactivated due to transformation or mutation that renders them permissive to viral oncolysis22,23,24. Even if these cancer cells have functional IFN response pathways, the absence of accessory cells, which may produce IFN constitutively or upon virus infection, in the in vitro culture system means that the tumor cells remain permissive. In this study, we show that tumor cells that retained interferon (IFN) responsive pathways can be protected in vitro by co-culture with macrophages, and in vivo, by tumor stromal elements (eg. tumor-associated macrophages, B cells, cancer associated fibroblasts, myeloid derived suppressor cells) which establishes an antiviral state that limits viral spread and therapeutic potential of oncolytic virotherapy.

Results

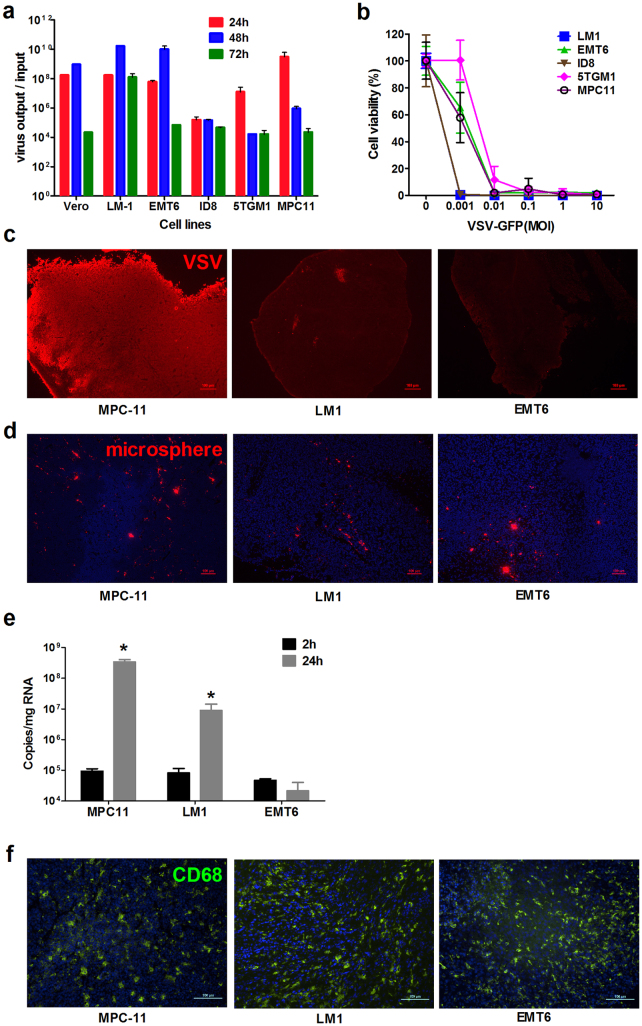

Tumor cells acquired resistance to VSV infection in vivo

Murine ovarian cancer cell lines LM-1 and ID-8, breast cancer cell line EMT-6, and myeloma cell lines 5TGM1 and MPC-11, are highly susceptible to VSV infection in vitro. These cancer cells support robust viral replication, yielding 108–1013 TCID50/ml of progeny virus by 24 h to 48 h post infection. These viral yields reflect a 104–1010 fold amplification of the input virus (Fig. 1a), indicating that these cancer cell lines are highly permissive to VSV replication and spread. Significant cell death was observed at both low and high multiplicities of infection (MOI 0.001–10.0) at 48 h post infection by VSV-GFP (Fig. 1b) confirming robust viral spread in all of the cell lines tested.

Figure 1. Susceptibility of tumor cells to VSV infection in vitro and in vivo.

(a) Propagation of VSV-GFP was quantitated by TCID50 titrations and fold increase in virus yield (virus output/input) is calculated (n = 3 replicates, mean ± SD). (b) Cell viability in VSV infected cultures was evaluated by the MTS assay at 48 h after infection at the respective MOIs. (c) Representative image of immunohistochemical staining for VSV protein (Alexa-555/red staining) in MPC-11, LM-1 and EMT-6 xenografts at 24 h post intravenous VSV delivery. (d) Red fluorescent 200 nm polystyrene microspheres in the tumors at 2 h after intravenous delivery. (e) Quantitative RT-PCR for VSV nucleocapsid mRNA in the tumors at 2 h or 24 h post virus delivery. Mean ± SD (n = 3 mice per time point). * P ≤ 0.05. Unpaired student t test was used. (f) Abundant and uniform distribution of CD68 cells (Alexa488/green staining) in the tumors. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

Notably, there was variability in tumor cell susceptibility to VSV infection and spread when they were grown as subcutaneous tumors in syngeneic mice. Immunohistochemical staining for VSV proteins showed that myeloma MPC-11 (Fig. 1c) and 5TGM1 (data not shown) tumors are highly susceptible to VSV oncolysis, supporting robust VSV infection and extensive viral spread after intravenous (IV) administration of 5 × 108 TCID50 of VSV-GFP. In contrast, VSV infection was minimal in LM-1 ovarian tumors and was undetectable in EMT-6 breast tumors at 24 h or at later time points post IV delivery of VSV (Fig. 1c).

Mice were injected intravenously with 200 nm red fluorescent microspheres to test perfusion of the tumors. The cryosections showed comparable delivery of the nanoparticles to the tumors (Fig. 1d). Tumors were also harvested 2 h after systemic infusion of 108 TCID50 VSV-GFP into the mice. Real time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) for VSV nucleocapsid (VSV-N) mRNA showed comparable virus delivery to the myeloma, ovarian and breast tumors at 2 h post virus infusion (Fig. 1e). While virus delivery was comparable, qRT-PCR analysis at 24 h showed robust VSV amplification in the myeloma tumors but significantly lower replication in the ovarian or breast tumors (Fig. 1e). To rule out the possibility that the systemically applied VSV did not reach the LM-1 or EMT-6 tumors, tumors were injected directly with 100 μl of VSV-GFP and harvested 24 h later. Results from immunohistochemical staining for VSV proteins were similar to the data in figure 1c, with minimal VSV signals in the LM-1 and EMT-6 tumors (data not shown).

The tumor microenvironment created by cellular infiltrates, for example, resident tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), is known to confer tumor resistance to a variety of chemotherapeutic agents26. It is conceivable that an antiviral state was induced by TAMs in the ovarian and breast tumors, conferring them with an antiviral state and resistance to VSV infection. Indeed, immunohistochemical staining revealed high numbers of CD68+ TAMs uniformly distributed throughout the tumor parenchyma (Fig. 1f).

Induction of an antiviral state by macrophages in vitro

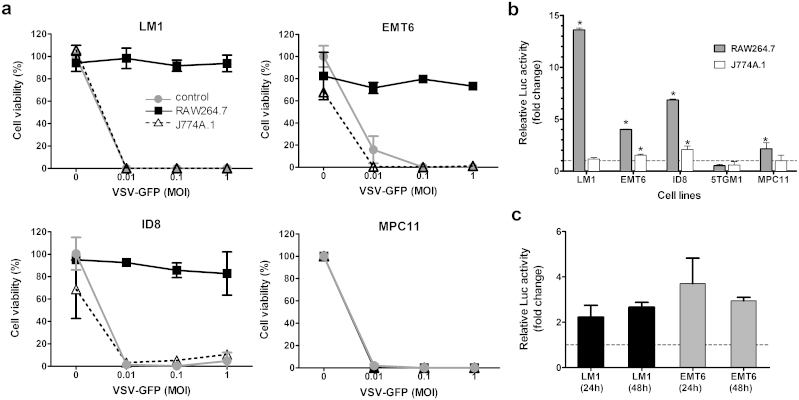

TAMs, through secreted cytokines or IFNs, might have induced an antiviral state by activating ISGs in the cancer cells. To test this hypothesis in vitro, the cancer cells were exposed for 24 h to conditioned media harvested from murine macrophage cell lines, RAW264.7 and J774A.1, after which VSV was added (MOI 0.01, 0.1, and 1.0) and cell viability was determined at 48 h post infection.

In all cell lines tested, 80–100% of cell killing was achieved at MOI of 0.01 if the cells were exposed to control media or J744.1 conditioned media (Fig. 2a). In contrast, RAW 264.7 conditioned media protected ovarian and breast cancer cells from VSV oncolysis (Fig. 2a). The extent of VSV-induced cell killing was significantly reduced; 80–90% of cells were still alive at MOI of 1.0. However, VSV oncolysis was robust in MPC-11 cells regardless of exposure to macrophage-conditioned media (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Effect of macrophage-conditioned media on VSV mediated killing of tumor cells.

(a) Cell killing by VSV-GFP. Cells were treated for 24 h with media alone or with conditioned media from RAW264.7 or J774A.1 before VSV exposure. MTS assays were performed 48 h post infection. Cell viability is presented as a percentage of uninfected cells. (b, c) Relative luciferase activity in ISRE-Luc tumor cells after (b) 24 h exposure to conditioned media from macrophage cell lines or (c) co-culture with primary peritoneal macrophages harvested from LM-1 and EMT-6 syngeneic mice, BALB/c and B6C3F1, respectively. Results represent fold change from control cells (media alone). N = 3 (mean ± SD). * P ≤ 0.05. Unpaired student t test was used.

To investigate if an antiviral state was induced through activation of interferon-stimulated genes, the cancer cells were stably transduced to express an IFN sensitive response element-luciferase (ISRE-Luc) reporter vector. Activation of JAK/STAT-mediated signal transduction pathways by signaling molecules (e.g. cytokines, type I IFN) would induce Luc gene expression, allowing quantitation of ISRE activation by measuring Luc activity27,28. Exposure to RAW 264.7 conditioned media, but not J774A.1, strongly activated Luc expression in ISRE-Luc ovarian (7–13 fold increase) and breast (4 fold) cancer cells and not in the myeloma cells (0.5–2 fold), supporting the hypothesis that soluble factors produced by RAW 264.7 macrophages have activated the ISRE and expression of IFN responsive genes (Fig. 2b). We next isolated primary macrophages from the peritoneal cavity of the respective syngeneic mice and co-cultured them with LM-1 or EMT-6 cells. As shown in figure 2c, ISRE-Luc activity was induced 2–4 folds in LM-1 and EMT-6 cells.

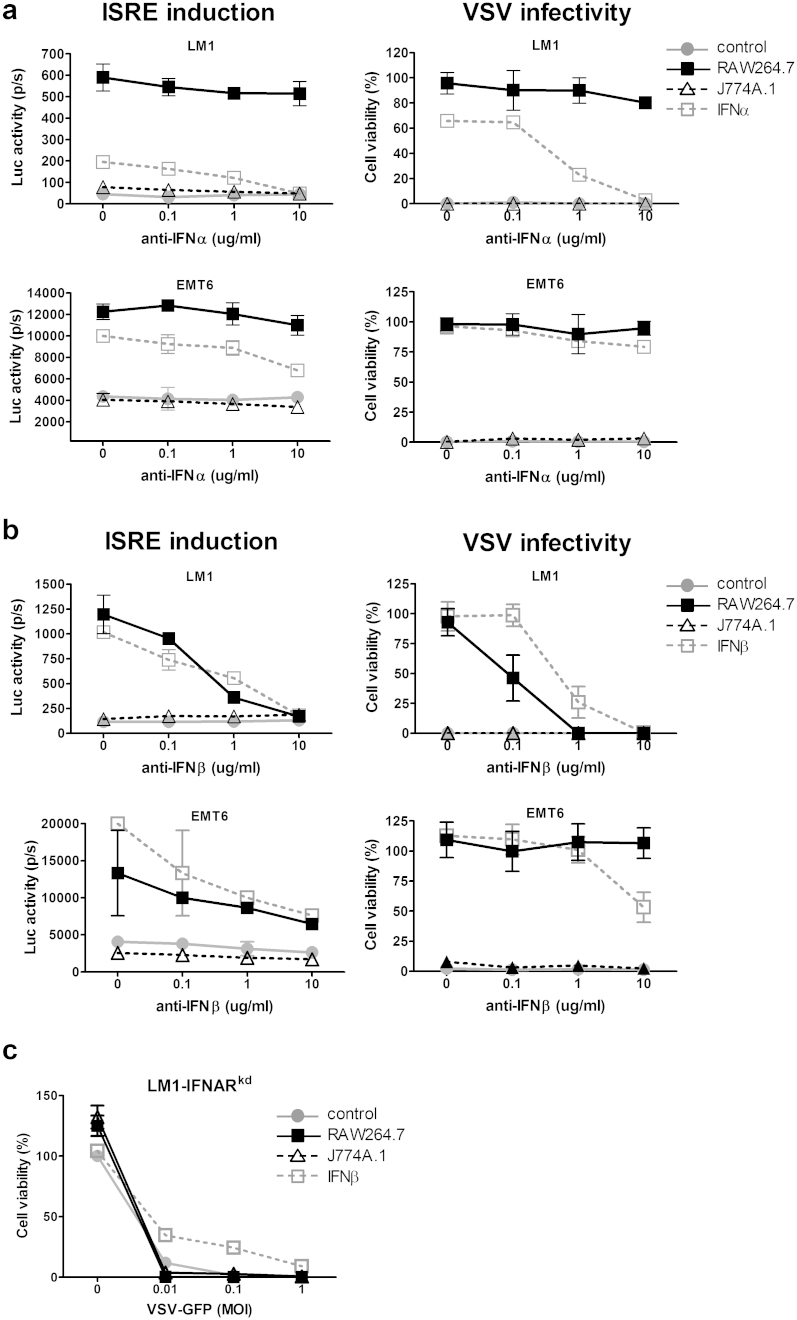

Macrophages constitutively express type I IFNs and confer viral resistance

To determine if activation of the ISRE was due to type I IFN, an ELISA assay was used to measure IFN-alpha (IFN-α) and IFN-beta (IFN-β) levels in the macrophage-conditioned media. No detectable IFN-α (limit of detection > 12.5 pg/ml) or IFN-β (limit of detection, >15.6 pg/ml) was found (data not shown). However, the antiviral state induced by exposure to RAW264.7 conditioned media or 10 U/ml IFN-α/β (positive control) can be reversed by addition of a neutralizing antibody against IFN-α or IFN-β. RAW 264.7 media exposed LM-1 cells became increasingly susceptible (Fig. 3a, anti-IFN-α) or totally susceptible (Fig. 3b, anti-IFN-β) to VSV oncolysis as the concentration of blocking antibody was increased. Unlike LM-1 cells, reversal of the antiviral state in EMT-6 cells was not complete even at 10 μg/ml of neutralizing antibody, suggesting that EMT-6 cells are more sensitive to IFNs than LM-1 cells. To further define the role of type I IFNs in mediating this antiviral state, LM-1 cells were stably transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding a shRNA against type I IFN receptor (IFNAR). These IFN-receptor knockdown LM-1 cells (LM-1-IFNARkd) are no longer responsive to the antiviral effects induced by exposure to conditioned media from RAW 264.7 macrophages and became totally susceptible to VSV oncolysis (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Acquired viral resistance is mediated by type I IFN in the conditioned media.

The effect of (a) anti-IFNα or (b) anti-IFNβ neutralizing antibodies on induction of luciferase expression in ISRE-Luc tumor cells and VSV mediated cell killing (MOI 1.0) of tumor cells that had been exposed 24 h to macrophage conditioned media or 10 U/ml IFNα or IFNβ. (c) IFN-receptor knockdown LM-1 cells (LM-1IFNARkd) are not responsive to the protective antiviral effects of RAW 264.7 macrophage conditioned media. Cells were exposed to the respective conditioned media and infected with VSV-GFP at indicated MOIs. Cell viability was determined 48 h later.

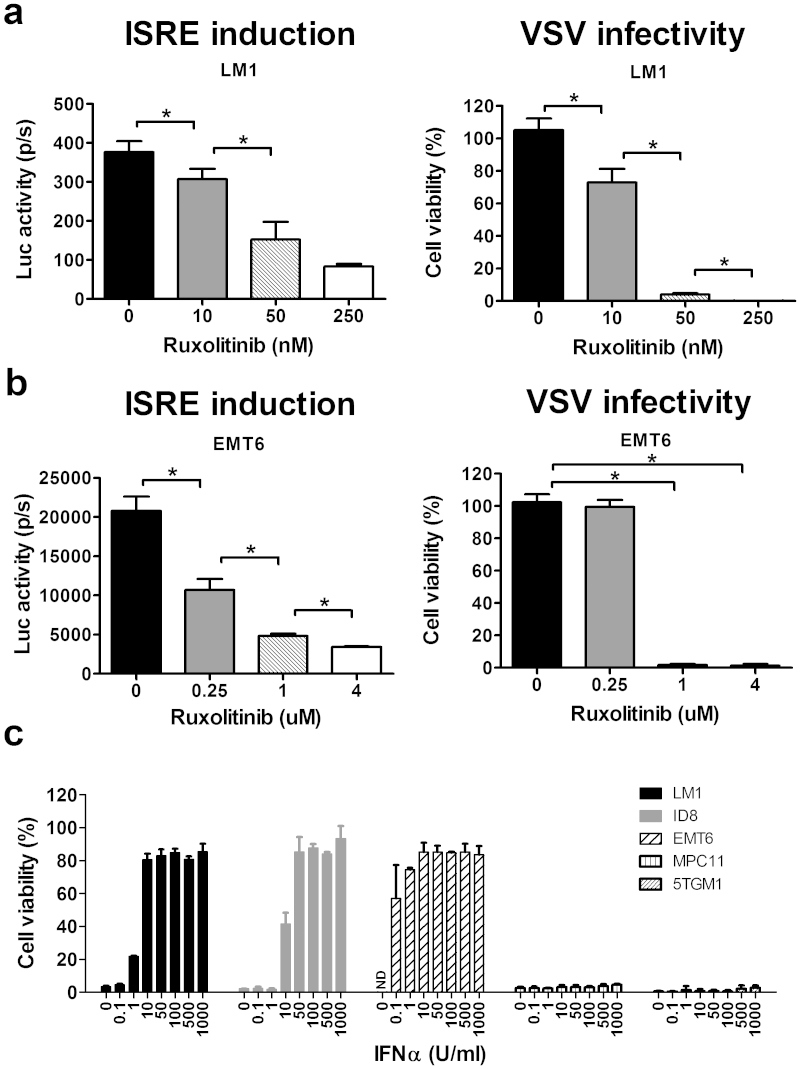

Reversal of the macrophage induced antiviral state by JAK inhibitors

Results from the above studies indicate that an antiviral state was induced by the macrophage-conditioned media through activation of ISRE, likely through activation of the JAK/STAT pathway via type I IFN. We thus tested the feasibility of using JAK inhibitors to block the signal transduction. LM-1 and EMT-6 cells were exposed to macrophage conditioned media as before, in the presence or absence of a JAK inhibitor, Jakafi™ (Ruxolitinib). Jakafi™ is a recently FDA approved drug for the treatment of myelofibrosis with an IC50 of 3.3 ± 1.2 nM and 2.8 ± 1.2 nM for JAK1 and JAK2, respectively.

The antiviral state induced in LM-1 and EMT-6 cells was reversed in a dose-dependent manner with increasing amounts of ruxolitinib in the conditioned media. Ruxolitinib at 250 nM was sufficient to block the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in LM-1 cells to achieve 100% VSV infectivity (Fig. 4a). In EMT-6 cells, 1 μM ruxolitinib was required to achieve 100% cell killing (Fig. 4b), suggesting that EMT-6 cells are very sensitive to the protective effects of IFN.

Figure 4. The effect of JAK inhibitors on the macrophage induced anti-viral state and relative sensitivity of cancer cell lines to type I IFN.

(a) ISRE-Luc expressing LM-1 and (b) EMT-6 cells were exposed to RAW264.7 conditioned media in the presence of ruxolitinib for 24 hours, after which the luciferase activity was measured (ISRE induction) or the cells were infected with VSV-GFP (MOI 1.0) and cell viability was determined 48 h later. Results represent mean ± SD of three different experiments. *P ≤ 0.05. Unpaired student t test was used. (c) Sensitivity of cancer cell lines to type I IFN was tested by pretreating the cells with the indicated concentrations of mouse IFNα for 24 h before VSV-GFP infection (MOI 1.0). Cell viability is presented as a percentage of the uninfected control.

To determine the relative sensitivity of the cancer cell lines to protection by IFN, the cells were treated with increasing doses of IFN-α. Addition of 1 U/ml of IFN-α was sufficient to protect 50% of LM-1 cells from VSV infection (Fig. 4c). EMT-6 cells were exquisitely sensitive to the antiviral effects of IFN-α. Only 0.1 U/ml of IFN-α (10 times less than LM-1) was sufficient to protect 60% of EMT-6 cells. In contrast, MPC-11 myeloma cells are totally unresponsive to IFN-α and remained highly susceptible to VSV oncolysis despite the addition of 1000 U/ml of IFN-α (Fig. 4c).

Pivotal antiviral regulators and genes are activated in tumors

We next investigated if an antiviral state was present in the LM-1 and EMT-6 tumors by performing semi-quantitative RT-PCR for various IFN sensitive genes (Fig. 5a). RNA was extracted from LM-1 and EMT-6 cells growing in tissue culture, from cells exposed to RAW264.7 and J774A.1 macrophage conditioned media or from subcutaneous non-treated tumors growing in syngeneic mice. The most significant change in mRNA profile was observed for IRF-7, OAS2 and MX2 genes. Exposure of LM-1 and EMT-6 cells to RAW 264.7 but not J744.1 macrophage conditioned media activated the transcription of IRF-7, OAS2 and MX2 antiviral genes. These genes were also activated in LM-1 and EMT-6 tumors harvested directly from the respective syngeneic mice. Relative intensities of the bands measured by dosimetric scanning estimate a 4.6-fold (LM-1) and 2.5-fold (EMT-6) increase in OAS2 mRNA and a 10-fold (LM-1) and 2.2-fold (EMT-6) increase in MX2 (Fig. 5b, c). Immunoblot analysis of the cells grown in culture and of tumor lysates showed strong expression of OAS2 and MX2 proteins in tumors but negligible in cancer cells (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. Expression profile of interferon sensitive genes (ISGs) and proteins in cancer cells and tumors.

(a) Semi-quantitate RT-PCR was used to determine the presence or absence of various ISG genes in LM-1 and EMT-6 cells, with or without exposure to conditioned media from RAW264.7 (RCM) or J774A.1 (JCM) or tumors grown in the respective syngeneic mice. Dosimetric measurements of the respective ISG bands in (b) LM-1 and (c) EMT-6 cells and tumors. Data represent fold increase from the respective control cells and was analyzed using Image J software. (d) Western blot analysis showing the presence or absence of two anti-viral proteins, OAS2 and Mx2, in the cells and tumors. Equivalent amount of protein (20 μg) was loaded for each lane. Blots shown in here were cropped using Photoshop software and the full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Activated ISG profiles in primary ovarian and breast cancers

The surprising finding that LM-1 and EMT-6 tumors exist in an antiviral state in vivo was evaluated further by mining the public microarray datasets (www.oncomine.org), comparing normal tissues versus tumor samples from breast cancer and ovarian cancer patients. Datasets with large sample sizes from the Gluck Breast study (n = 158), Bonome Ovarian study (n = 195), and the Cancer Genome Atlas project (TCGA, n = 517 for ovarian and n = 137 for breast) were interrogated (Table 1). IFN-related genes that showed the most significant increases in our study above, IRF7, IRF9, MX2, STAT1, and OAS2, and representative members of other IFN-related genes, MX1, OAS1, STAT1, JAK1, TYK1, IFNAR1, IFNAR2, were analyzed. As shown in Table 1, the majority of these genes including all the genes that showed significant increases in semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5a.) were significantly higher in tumors compared to the normal control tissues. Antiviral genes, MX1, MX2, OAS1 and OAS2 showed the highest increase (1.5–4 folds). Expression of genes upstream in the JAK/STAT pathway, JAK1, TYK2, IFNAR1, and IFNAR2, were either decreased or showed no significant change.

Table 1. Expression profile of antiviral genes from public microarray database.

| Gluck Breast (Invasive Breast Carcinoma vs. Normal = 154 vs. 4) | TCGA Breast (Invasive Breast Carcinoma vs. Normal = 76 vs. 61) | Bonome Ovarian (Ovarian Carcinoma vs. Normal = 185 vs. 10) | TCGA Ovarian (Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma vs. Normal = 509 vs. 8) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENE | P-value | FC* | P-value | FC* | P-value | FC* | P-value | FC* |

| IRF7 | 0.002 | 1.369 | 1.29E-23 | 2.764 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| IRF9 | 0.003 | 1.634 | 2.22E-10 | 1.765 | 1.49E-07 | 2.04 | 0.141 | 1.165 |

| MX1 | 0.002 | 1.935 | 1.36E-6 | 1.865 | 0.013 | 1.208 | 0.009 | 1.613 |

| MX2 | 0.19 | 1.213 | 2.25E-11 | 2.004 | 4.61E-05 | 1.664 | 3.12E-04 | 3.933 |

| OAS1 | 0.001 | 1.939 | 6.70E-14 | 2.379 | 0.012 | 1.528 | 1.25E-04 | 3.226 |

| OAS2 | 1.64E-5 | 2.059 | 1.65E-23 | 4.788 | 3.29E-04 | 1.495 | 3.46E-04 | 2.490 |

| STAT1 | 6.28E-4 | 1.843 | 2.66E-18 | 2.798 | 0.999 | −1.587 | 1.87E-06 | 2.999 |

| STAT2 | 7.74E-4 | 2.196 | 3.97E-7 | 1.295 | 3.89E-9 | 1.519 | 1.50E-4 | 1.262 |

| JAK1 | 0.940 | −1.404 | 0.681 | −1.061 | 1.000 | −2.923 | 1.000 | −1.316 |

| TYK2 | 0.012 | 1.502 | 1.84E-11 | 1.609 | 0.024 | 1.168 | 3.66E-4 | 1.226 |

| IFNAR1 | 0.677 | −1.102 | 0.028 | 1.298 | 0.862 | −1.072 | 0.976 | −1.093 |

| IFNAR2 | 0.003 | 1.339 | 0.093 | 1.141 | 0.994 | −1.230 | 0.308 | 1.075 |

*FC = Fold Change.

Discussion

This study is the first report demonstrating that cancer cells that are highly susceptible to infection and killing by an oncolytic virus in vitro can acquire a formidable antiviral state in vivo to become refractory to virotherapy. Analyses of explanted tumors at 2 h post virus infusion confirmed virus delivery but subsequent virus infection and spread was inhibited in these tumors. As shown in this study, not all tumors exist in an antiviral state; it is those cancer cells that have a functional IFN and JAK/STAT responsive pathway and are exquisitely sensitive to IFN that present with a different (i.e. virus resistant) phenotype in vivo. The in vivo source of IFN is likely from the tumor infiltrating immune cells, as lymphocytes and macrophages are known to constitutively secrete very low endogenous levels of IFN27.

The tumor microenvironment is composed of proliferating tumor cells and the tumor stroma comprising extracellular matrix, blood vessels, infiltrating inflammatory cells and a variety of accessory cells29. Tumor cells produce cytokines and chemokines that recruit inflammatory cells that support tumor neovascularization, growth and metastasis30,31,32. These tumor-infiltrating cells also play important roles in adaptive immunity (T lymphocytes, dendritic cells, B cells) and innate immunity (tumor associated macrophages TAMs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes and natural killer cells). Presence of these immune cells is often correlated with a poor prognosis in breast, cervical, bladder and lung cancers33,34,35,36,37. The infiltrating inflammatory cells, specifically TAMs with CD4hiCD68hiCD8low, enhance tumor resistance to chemotherapy and/or are immunosuppressive26,38.

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells are of interest in virotherapy because lymphocytes and macrophages are found to constitutively express low levels of type I IFN at levels that cannot easily be detected by conventional biological assays or immunoassays27. Type I IFN and Type II IFN constitute an important element of the host innate immune response to control virus infection39,40. Type I IFN, IFN-α and IFN-β, induce antiviral activity by binding to IFNAR1/2 receptors, which results in phosphorylation of the receptor by JAKs and recruitment and phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 which together with IRF9 form a transcription factor, IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). ISGF3 recognizes ISRE that controls transcription of ISGs, many of which have direct antiviral functions or contribute to the formation of the antiviral state41,42. Several of these ISGs, ISG15, MxA, OAS and PKR, have been shown to inhibit replication of rhabdoviruses such as VSV41,43.

It is not clear why immune cells constitutively express type I IFN. It has been proposed that immune cells specifically express specific IFN genes independently of one another (there are currently 13 subtypes of IFNα and 2 types of IFNβ), so that certain genes are expressed at high levels only in response to virus infection whereas others are expressed constitutively at low levels and respond only poorly or not all to virus infections27. The authors showed that PBMC and U937, a human myeloid monocytic cell line, constitutively produce IFNα5 and IFNβ in the absence of virus, in contrast to the expression of multiple IFN subspecies (including IFN-α1, IFN-α2, IFNβ) post virus exposure27. The culture supernatant from uninduced U937 cells contains about 0.3–0.5 U/ml of IFN and activates the ISRE in the ISG15 gene. Freshly harvested peritoneal macrophages can also confer an antiviral state on mouse embryonic fibroblasts44, and as shown here, in IFN responsive tumor cells. The conferred antiviral state is inhibited by neutralizing antibodies to IFNα/β. Interferon spontaneously expressed in normal mice and maintain the host cells in an antiviral state, possibly as a part of an integral host defense against viral infection44.

While it is generally assumed that most cancer cells are defective in type I IFN responses and do not produce IFN41,45,46,47, studies have shown that some cancers cells, such as PC3 prostate cancer cells, SW982 human sarcoma cells, and multiple mesothelioma cells lines, do retain the ability to respond to type I IFN and are resistant to VSV infection, at least in part due to IFN responsiveness and/or constitutive ISG expression41,48,49,50. Unlike the cells stated above, the ovarian and breast cancer cell lines, LM-1 and EMT-6 cells used in this study do not exist in a constitutive antiviral state in vitro and are highly permissive to VSV replication. However, they are exquisitely sensitive to the antiviral effects of type I IFN. When co-cultured with macrophages or macrophage conditioned media, low levels of IFN produced constitutively by the murine macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7, or by freshly harvested peritoneal macrophages activated the ISRE in LM-1 and EMT-6 cells, resulting in activation of ISGs and induction of a formidable antiviral state in these cancer cells in vitro. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and western blot analysis of the syngeneic murine ovarian and breast tumors confirmed elevated levels of mRNA and protein of key antiviral ISGs when compared to the cells grew in vitro. Global expression profile microarray analyses of primary human ovarian and breast tumors showed 2–4 fold higher levels of antiviral ISG mRNA in primary tumors compared to their normal counterparts (n = 712 for ovarian samples and n = 295 for breast samples, Table 1). A more extensive survey of other murine tumors, which were highly sensitive to VSV infection and oncolysis in vitro, but were resistant to VSV infection and therapy in vivo was also noted in LLC lung cancer, CMT-93, EL4 lymphoma and RENCA renal cell cancers (Peng and Russell, unpublished data).

We are currently screening a variety of drugs that can potentially block IFN or Jak/Stat signaling to synergize with VSV therapy. Several JAK mutations that result in constitutively active or hyperactive JAK proteins, which have crucial roles in hematopoietic malignancies, especially myeloproliferative neoplasms, have been identified51. Jak1/2 inhibitors, including AG490 and Jakafi™ (Ruxolitinib) are being evaluated as anticancer drugs52. Our in vitro study showed that ruxolitinib can reverse the antiviral state and block the activation of JAK/STAT pathway induced by the macrophage conditioned media in the ovarian and breast cancer cell lines to achieve 100% VSV infectivity in vitro. These results support future studies to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combining oncolytic virotherapy with JAK inhibitors as a strategy to dampen innate immunity. Future oncolytic virotherapy clinical studies could also incorporate assessment of the global gene expression profile of the tumors to determine the correlations between the antiviral state with extent of viral replication and response to the therapy.

Methods

Cells and viruses

EMT-6 murine mammary carcinoma, LLC1 murine Lewis lung carcinoma, MPC-11 murine myeloma, RAW264.7, and J774A.1 murine monocyte/macrophage cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Murine ovarian cancer cells LM-1 and ID-8, murine ovarian carcinoma, were obtained from Dr. A. Al-Hendy, University of Saskatchewan and Dr. K. Roby, University of Kansas Medical Center, respectively. All of the above cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). 5TGM1 cells (gift from Dr. B. Oyajobi, University of Texas Health Science Center) were grown in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 20% FBS. All media contained penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics.

The ISRE (Interferon Stimulated Response Element)-luciferase transduced cancer cells were generated by transduction with lentiviral particles expressing luciferase under the control of ISRE (Lenti-ISRE-Luc, Qiagen, Frederick, MD). For type I IFN receptor (IFNAR1) knocked down cells, lentiviral particles encoding shRNA against were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Following lentiviral transduction, cells were selected and maintained under puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) selection.

Recombinant VSV-GFP virus was amplified in Vero cells as previously described25. Viruses were purified by 0.45 μm filtration of cell supernatant and pelleted by ultra-centrifugation (27,000 rpm) through a 10% w/v sucrose gradient. Viral titer was determined by TCID50 (median tissue culture infective dose) titrations on Vero cells.

In vitro infection and viral replication analysis

To prepare the macrophage-conditioned media, 1.4 × 105 RAW264.7 or J774A.1 cells were seeded in 12 well plates and 6 hours later, standard growth media was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 0.5%BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Forty-eight hours later, the media were collected and filtered using 0.22 μm membrane (Millipore, Carrigtwohill, County Cork, Ireland), aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

For the virus infection assays, cells (7000 cells/well in a 96 well plate) were exposed to VSV-GFP at the specified MOI in the presence or absence of conditioned media. Cell viability was assessed at 48 hours post infection using the MTS cell proliferation assay according to manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). For the viral replication assays, 1.4 × 105 cells were seed in 12 well plates and infected with VSV-GFP (MOI 0.02 in 1 ml Opti-MEM) and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. The virus inoculum was removed, cells were washed with PBS and growth media was replaced. Cells and media were collected at 24, 48 and 72 hours post infection and stored at −80°C until analysis. Viral titers were determined by TCID50 plaque-forming assay on Vero cells as mentioned above.

Type I IFN neutralization and sensitivity analysis

Mouse IFNα, mouse IFNβ, rat monoclonal antibody against mouse IFNα, and rat monoclonal antibody against mouse IFNβ were all purchased from PBL Interferon Source (Piscataway, NJ). ISRE-Luc cells in the 96 well plates were either infected with VSV-GFP (MOI1.0) or lyzed with cell-culture lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) 24 hours after exposure to murine IFN in the presence or absence of anti-IFN neutralizing antibodies. Cell viability was determined using the MTS assay at 48 hours after infection. Luciferase activity was measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) and read on an Infinite M200 PRO luminometer (TECAN, Research Triangle Park, NC). All data are expressed as either fold change or relative light units (RLU).

JAK-STAT pathway inhibitor

Ruxolitinib was purchased from ChemieTek (Indianapolis, IN). 7,000 cells/50 μl growth media were seeded in 96 well plates. Six hours later, growth media containing ruxolitinib (10, 50, and 250 nM for LM1 cells; 0.25, 1, 4 μM for EMT-6 cells) were added. Twenty-four hours later, ISRE-Luc cells were either infected with VSV-GFP (MOI 1.0) and cell viability was determined 48 h after infection or lyzed with cell lysis buffer and luciferase activity measured as described above.

Animal experiments

All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Five to six week old female mice were implanted subcutaneously in the right flank with tumor cells. LM-1 cells (2 × 106 cells/site) were grown in B6C3F1 J mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY), MPC-11 (5 × 106 cells/site) and EMT-6 (2 × 106 cells/site) were grown in BALB/c mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) and 5TGM1 cells (5 × 106 Cells/site) were grown in C57Bl/KaLwRij mice (Harlan Netherlands, Horst, The Netherlands). For mRNA or immunohistochemical studies, tumors were harvested into RNAlater (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or frozen (−20°C) in Optimal Cutting Media (OCT) when they were 0.8 to 1.0 cm in diameter. In some cases, mice received VSV-GFP intravenously (5 × 108 TCID50) or 50 μl of red fluorescent 200 nm polystyrene microspheres (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and tumors were harvested 2 or 24 hours later into RNAlater or snap frozen for storage at −80°C.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor samples frozen in optimal cutting temperature medium (OCT) were sectioned (5 μm), fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.01% Triton-X/PBS for 15 min. Blocking buffer containing 5% horse serum/PBS was applied for 20 min, after which tissues were incubated with rat anti-murine CD68 antibody (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) or polyclonal rabbit anti-VSV antibodies generated in-house by the Mayo Clinic Viral Vector Production Laboratory for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were washed five times in PBS, followed by incubation with Alexa 488 conjugated anti-rat antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or Alexa 555 conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min after which the slides were viewed under fluorescence light with an inverted Nikon (Eclipse E400) and images captured with QIClick digital camera with NIS Elements software (Nikon).

Immunoblotting for antiviral genes

Protein lysates fractionated by 10% acrylamide SDS-PAGE were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)–Tween for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with primary antibodies, rabbit anti-mouse OAS2, rabbit anti-human MX1/2/3, or goat anti-actin (SantaCruz, Dallas, Texas). After five washes in TBS-Tween, membranes were incubated with the appropriate peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies. Signal was developed using Pierce ECL western blotting substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Tumor RNA extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR for VSV-N or Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR for antiviral genes

Tumors were preserved in RNAlater® (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) at the time of necropsy. Before RNA extraction, tumors were homogenized in a TissueLyser II instrument with stainless steel beads. RNA was extracted by the RNeasy® Plus Universal Mini Kit (Qiagen, Frederick, MD). For quantitative RT-PCR, RNA samples were diluted to 0.2 μg per reaction (total sample volume of 5 μL). Samples were quantified by comparison with a standard curve generated by amplification of 432-bp in vitro-transcribed RNA (MAXIscript SP6 kit; Applied Biosystem) encoding a 298-base portion of the VSV nucleoprotein gene (bases 972–1269) cloned in pCR®II-TOPO® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All samples and standards were run in triplicate. For semi-quantitative RT-PCR, 1 μg of total RNA for each samples were used for the generation of cDNA. Reverse transcription was performed using a SuperScript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and oligo(dT) primer according to manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification reactions were then performed using antiviral gene specific primers. The mRNA expression of target genes was normalized against the respective GAPDH mRNA levels.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of experimental results was analyzed by unpaired student's t test where indicated. A p value of <0.05 is considered statistically different.

Author Contributions

Y.-P.L. and K.-W.P. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript. Y.-P.L., L.S. and M.B.S. performed the experiments. K.-W.P. and S.J.R. proposed and supervised the project.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1

Acknowledgments

We thank Asha Nair and Dr. Ying Li (Mayo Clinic, Biomedical Statistics and Informatics) for help with analysis of the microarray data and Dr. Mark Federspiel (Mayo Clinic, Molecular Medicine) for the kind gift of anti-VSV antibody. We acknowledge funding support from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA129196, R01CA136547, the Mayo Clinic Ovarian SPORE (P50CA136393) and the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

S.J.R. and K.-W.P. are cofounders of Omnis Pharma, an oncolytic VSV company.

References

- Russell S. J., Peng K. W. & Bell J. C. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nature biotechnology 30, 658–670 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eager R. M. & Nemunaitis J. Clinical development directions in oncolytic viral therapy. Cancer gene therapy 18, 305–317 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollmann G., Ozduman K. & van den Pol A. N. Oncolytic virus therapy for glioblastoma multiforme: concepts and candidates. Cancer J 18, 69–81 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. H., Hermiston T. & Kirn D. Oncolytic virotherapy: approaches to tumor targeting and enhancing antitumor effects. Semin Oncol 32, 537–548 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E. J. & Russell S. J. MicroRNAs and the regulation of vector tropism. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 17, 409–416 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchefeu Y., Franken P. & Harrington K. J. Radiovirotherapy: principles and prospects in oncology. Curr Pharm Des 18, 3313–3320 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennier S. T., Liu J. & McFadden G. Bugs and drugs: oncolytic virotherapy in combination with chemotherapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 13, 1817–1833 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney D. J. & Stojdl D. F. Molecular pathways: multimodal cancer-killing mechanisms employed by oncolytic vesiculoviruses. Clin Cancer Res 19, 758–763 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridle B. W., Hanson S. & Lichty B. D. Combining oncolytic virotherapy and tumour vaccination. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 21, 143–148 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik S. & Russell S. J. Engineering oncolytic viruses to exploit tumor specific defects in innate immune signaling pathways. Expert opinion on biological therapy 9, 1163–1176 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestwich R. J. et al. Oncolytic viruses: a novel form of immunotherapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 8, 1581–1588 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivendran S., Pan M., Kaufman H. L. & Saenger Y. Herpes simplex virus oncolytic vaccine therapy in melanoma. Expert opinion on biological therapy 10, 1145–1153 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher A., Parato K., Rooney C. M. & Bell J. C. Thunder and lightning: immunotherapy and oncolytic viruses collide. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 19, 1008–1016 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik S., Nace R., Barber G. N. & Russell S. J. Potent systemic therapy of multiple myeloma utilizing oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus coding for interferon-beta. Cancer gene therapy 19, 443–450 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Breckenridge C. A. et al. NK cells impede glioblastoma virotherapy through NKp30 and NKp46 natural cytotoxicity receptors. Nat Med 18, 1827–1834 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K. et al. Oncolytic virus therapy of multiple tumors in the brain requires suppression of innate and elicited antiviral responses. Nat Med 5, 881–887 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. A. et al. Immunosuppression enhances oncolytic adenovirus replication and antitumor efficacy in the Syrian hamster model. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 16, 1665–1673 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng K. W. et al. Using clinically approved cyclophosphamide regimens to control the humoral immune response to oncolytic viruses. Gene Ther 20, 255–261 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbach C. J. et al. Targeting tumor vasculature with an oncolytic virus. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 19, 886–894 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E., Breznik J. & Lichty B. D. Strategies to enhance viral penetration of solid tumors. Human gene therapy 22, 1053–1060 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia A. L. & Bissell M. J. The tumor microenvironment is a dominant force in multidrug resistance. Drug Resist Updat 15, 39–49 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M., Porosnicu M., Markovic D. & Barber G. N. Genetically engineered vesicular stomatitis virus in gene therapy: application for treatment of malignant disease. J Virol 76, 895–904 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojdl D. F. et al. Exploiting tumor-specific defects in the interferon pathway with a previously unknown oncolytic virus. Nat Med 6, 821–825 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Elsen P. J., Holling T. M., van der Stoep N. & Boss J. M. DNA methylation and expression of major histocompatibility complex class I and class II transactivator genes in human developmental tumor cells and in T cell malignancies. Clin Immunol 109, 46–52 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel A. et al. Radioiodide imaging and radiovirotherapy of multiple myeloma using VSV(Delta51)-NIS, an attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus encoding the sodium iodide symporter gene. Blood 110, 2342–2350 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma M. & Lewis C. E. Cancer: Macrophages limit chemotherapy. Nature 472, 303–304 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand C., Lebon P., Rizza P., Blanchard B. & Tovey M. G. Constitutive expression of specific interferon isotypes in peripheral blood leukocytes from normal individuals and in promonocytic U937 cells. J Leukoc Biol 60, 137–146 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A., Parisien J. P. & Horvath C. M. STAT2 is a primary target for measles virus V protein-mediated alpha/beta interferon signaling inhibition. J Virol 82, 8330–8338 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside T. L. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene 27, 5904–5912 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A., Sica A., Allavena P., Garlanda C. & Locati M. Tumor-associated macrophages and the related myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a paradigm of the diversity of macrophage activation. Hum Immunol 70, 325–330 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamarron B. F. & Chen W. Dual roles of immune cells and their factors in cancer development and progression. Int J Biol Sci 7, 651–658 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthana M. et al. Use of macrophages to target therapeutic adenovirus to human prostate tumors. Cancer Res 71, 1805–1815 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppmann S. F. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages express lymphatic endothelial growth factors and are related to peritumoral lymphangiogenesis. Am J Pathol 161, 947–956 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppmann S. F. et al. VEGF-C expressing tumor-associated macrophages in lymph node positive breast cancer: impact on lymphangiogenesis and survival. Surgery 139, 839–846 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. J. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: the double-edged sword in cancer progression. J Clin Oncol 23, 953–964 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada T. et al. Prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophage count in human bladder cancer. Int J Urol 7, 263–269 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. W., Shen S. C., Ko C. H., Lin H. Y. & Chen Y. C. Reciprocal activation of macrophages and breast carcinoma cells by nitric oxide and colony-stimulating factor-1. Carcinogenesis 31, 2039–2048 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo D. G. et al. Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov 1, 54–67 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S. & Banerjee A. K. Innate immune response against nonsegmented negative strand RNA viruses. J Interferon Cytokine Res 23, 401–412 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu M. et al. Inhibition of vesicular stomatitis virus infection in epithelial cells by alpha interferon-induced soluble secreted proteins. J Gen Virol 87, 2653–2662 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerdyk-Schauwecker M. et al. Resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus: role of type I interferon signaling. Virology 436, 221–234 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark G. R., Kerr I. M., Williams B. R., Silverman R. H. & Schreiber R. D. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 227–264 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler A. J. & Williams B. R. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol 8, 559–568 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proietti E., Gessani S., Belardelli F. & Gresser I. Mouse peritoneal cells confer an antiviral state on mouse cell monolayers: role of interferon. J Virol 57, 456–463 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie E. & Grdzelishvili V. Z. Vesicular stomatitis virus as a flexible platform for oncolytic virotherapy against cancer. J Gen Virol 93, 2529–2545 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber G. N. Vesicular stomatitis virus as an oncolytic vector. Viral Immunol 17, 516–527 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichty B. D., Power A. T., Stojdl D. F. & Bell J. C. Vesicular stomatitis virus: re-inventing the bullet. Trends Mol Med 10, 210–216 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M., Cramer S. D. & Lyles D. S. Sensitivity of prostate tumors to wild type and M protein mutant vesicular stomatitis viruses. Virology 330, 34–49 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglino J. C. & van den Pol A. N. Vesicular stomatitis virus has extensive oncolytic activity against human sarcomas: rare resistance is overcome by blocking interferon pathways. J Virol 85, 9346–9358 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloura V. et al. Evaluation of an attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus vector expressing interferon-beta for use in malignant pleural mesothelioma: heterogeneity in interferon responsiveness defines potential efficacy. Human gene therapy 21, 51–64 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu S. N., Girardot M. & Pecquet C. Mining for JAK-STAT mutations in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci 33, 122–131 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone P. & Bromberg J. Targeting the interleukin-6/Jak/stat pathway in human malignancies. J Clin Oncol 30, 1005–1014 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1