Abstract

Background

Next to the school environment, the family and community environment are key for young people’s behaviour and for promoting physical activity (PA).

Methods

A ‘review of reviews’ was conducted, after which a literature search was conducted (in PubMed, Scopus and PsychInfo) from Aug-2007 (search date of the most recent review) to Oct-2010. Inclusion criteria: study population ≤18yrs, controlled trial, ‘no PA’ control condition, PA promotion intervention, and reported analyses of a PA-related outcome. Methodological quality was assessed and data on intervention details, methods and effects on primary and secondary outcomes (PA, body composition and fitness) were extracted.

Results

Three previous reviews were reviewed, including 13 family-based and three community-based interventions. Study inclusion per review differed, but all concluded that the evidence was limited although the potential of family-based interventions delivered in the home and including self-monitoring was highlighted. A further six family-based and four community-based were included in the updated review, with a methodological quality score ranging from 2-10 and five studies scoring 6 or higher. Significant positive effects on PA were observed for one community-based and three family-based studies. No distinctive characteristics of the effective interventions compared to those that were ineffective were identified.

Conclusions

The effect of family- and community-based interventions remains uncertain despite improvements in study quality. Of the little evidence of effectiveness, most comes from those targeted at families and set in the home. Further detailed research is needed to identify key approaches for increasing young people’s PA levels in family and community settings.

INTRODUCTION

The current generation of young people are generally thought to be insufficiently active to benefit their health,1 2 with levels of physical activity declining throughout childhood and adolescence.3 Effective strategies are therefore needed to encourage changes in physical activity behaviour among young people, whether it is promoting maintenance of physical activity levels in younger children, preventing decline in primary school-aged children or promoting increases in adolescents. School is often the preferred setting for health promotion in young people given the large amount of time that they spend there.4 However, health behaviours are known to be influenced by a variety of factors at a number of ecological levels, of which the school setting is only one.5 The family environment and the community in which young people live in or belong to are also thought to have an important influence on their health behaviours. This ecological perspective on health behaviour has gained in popularity in the past decade, whereas simultaneously physical activity promotion in young people was identified as a key focus of efforts to promote population health in various international policy documents.6 7 This has resulted in an increase in efforts to evaluate physical activity promotion interventions in young people in various settings. This review therefore explores the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents, delivered in the family and community setting, summarising previous reviews and updating the evidence with findings from recently conducted controlled trials.

METHODS

This review applies a mixed-methods strategy. Three systematic reviews on physical activity promotion in children and adolescents, including a focus on family and community interventions,8-10 will be reviewed in the first part of this review, covering the available evidence up to the date of the most recent search (August 200710). In the second part of this review, an updated literature review will be conducted covering publications between August 2007 and October 2010, to establish the effectiveness of more recent efforts.

Updated literature review

Literature search

A literature search was conducted based upon the methods of a previous review.9 Using the same search terms, with a limited focus on community and family settings, we searched PubMed, Scopus and PsychInfo in November 2010 (see Supplementary Table 1). Inclusion criteria were: 1) study population of healthy young people (≤ 18 years); 2) promotion of physical activity through behaviour change as a main intervention component; 3) intervention delivered outside of the school or primary care setting; 4) the control group received no or a non-physical activity intervention; and 5) reported statistical analyses of a physical activity outcome measure. Weight status was not an exclusion criterion, although we excluded studies solely recruiting from clinical settings or studies including children with other health problems. One reviewer (EvS) checked the titles obtained from the searches, after which both reviewers each reviewed half of the resulting abstracts. Full text studies were obtained and reviewed by both reviewers independently and discrepancies were resolved after discussion.

For the purpose of this review, we considered all interventions that were outside of the school setting and not delivered in a clinical setting to be community interventions. Interventions set in the school and including a family or community component are reviewed in a related review in this special issue.11 We further classified some of these interventions as family interventions if they included the active participation of one or more family members of the child. All interventions targeted at the individual child only were categorised as community-based. After-school interventions offered only to children at that specific school were considered to be an extension of the school setting and were therefore not included in this review. Interventions that used school facilities but were made available to all children in the neighbourhood/community (irrespective of whether or not they attended a specific school) were considered community-based interventions.

Methodological quality

We assessed the methodological quality for descriptive purposes using a previously applied 10-item rating system.9 The assessment focussed on internal validity and statistical analyses, including randomisation, validity of the physical activity measure, blinding and intention-to-treat analyses. All items were scored as ‘positive’, ‘negative’ or ‘not, or insufficiently, described’ by two reviewers independently. In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached by discussion. Only positive scores were accumulated; studies were considered of high quality if they scored 6 or more for randomised controlled trials (RCT) or 5 or more for controlled trials (CT).

Summarizing the evidence

Information on the intervention content, target population, evaluation methods and results on physical activity (and body composition and fitness where provided) were extracted by one reviewer (AM). A narrative account of the evidence is provided. We compared interventions and their evaluations on the intervention strategies applied, the populations targeted and methodology used to help identify whether there were common components potentially explaining the intervention effect.

RESULTS

Summary of previous reviews

Table 1 provides an overview of the methodology and results of the three recent systematic reviews on physical activity promotion in children and adolescents. Using the definitions described earlier for our updated review, a total of 13 family-12-24 and 3 community-based25-27 studies were included across the three previous reviews, with no single review including all studies. Six of the family-based interventions were reported to have a significant positive effect on physical activity16 19 21-24 while none of the community-based interventions were. Below we summarise the findings from each review, however, it should be noted that the interpretation of family- and community-based interventions varied across the reviews, in some cases leading to the same intervention being classified differently. Additionally, the reviews differed in their assessment of methodological quality, evidence synthesis, in- and exclusion criteria and the stratification for presenting the results (based on age or weight status). However, despite these differences, the reviews drew broadly similar conclusions.

Table 1.

Summary of previously published reviews on physical activity promotion in children with a focus on family- and community-based interventions (presented in chronological order).

| Reference | Review type | Search (databases & period) |

Main inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Number & references of studies included a,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon et al 20075 |

Narrative review |

Medline and Premedline; Sportsdiscus; PsychInfo; Psyc-ARTICLES; Cochrane; CINAHL; ScienceDirect; Web of Knowledge; Social SciSearch; all Ovid databases (01/1985-06/2006) |

1) children (4–12 years) or adolescents (13–19 years); 2) report of PA outcomes (studies that only reported on fitness outcomes were excluded); 3) sample size of more than 16; and 4) RCT, group randomized trial, or quasi-experimental study design. |

Studies only reporting fitness or health outcomes; overweight or obesity treatment studies; studies of clinical populations. |

Family setting: 9 studies (8 children).12- 16, 17, 19, 23, 28, 29 Community setting: 3 studies (all children).25, 30, 31 |

| Van Sluijs et al 20076 |

Systematic review, assessing methodological quality. Conclusions drawn using levels of evidence. |

Pubmed, Psychlit, SCOPUS, Ovid Medline, Sportdiscus, and Embase (inception-12/2006) |

1) children (<12 years) or adolescents (≥12 years); 2) main intervention component or one of the components was aimed at promotion of PA through behaviour change; 3) inclusion of a non-PA intervention for the control group; and 4) reported statistical analyses of a PA outcome measure. |

Interventions aimed at reducing sedentary behaviour or structured exercise programs; studies of populations selected on basis of specific disease or health problem. |

Family setting: 5 studies (4 children).13, 15, 17, 18, 20 Community setting: 3 studies (2 children).14, 26, 27 |

| NICE 20097 | Systematic review, assessing methodological quality. Narrative account of studies and results. |

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, HMIC, Sportsdiscus, ASSIA, SIGLE, Current Contents, ERIC, TRANSPORT, Environline, EPPI Centre Databases, NRR (inception-08/2007) |

1) Intervention study; 2) age group studied aged ≤ 18 years; 3) based in a family or community setting; and 4) outcome reported on PA behaviour or core physical skills. |

Main focus on treating obesity; studies from less economically developed countries or primarily investigating ethnic groups that do not have large populations in England; interventions primarily based within the school curriculum; environmental interventions (covered in previous NICE guidance); study included within one of the other four reviews in the series (e.g. adolescent girls). |

Family setting: 11 studies (8 children).13- 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 32, 33 Community setting: 2 studies (adolescents).27, 34 |

PA: Physical activity, CT: controlled trial, RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Other categories reported but excluded for this review: Salmon et al 2007: school (including sub-categories), primary care; van Sluijs et al 2007: school, school plus community or family, primary care; NICE 2009: primary care, out of school hours clubs, schools and family.

References presented in bold were presented as effective in increasing young people’s physical activity.

Salmon et al8 reviewed the available evidence up to June 2006 and included both controlled and uncontrolled studies. In their narrative account of the literature, they highlighted the strategies applied and potential methodological strengths and weaknesses. Of the nine included interventions conducted in the family setting,12-17 19 23 28 29 seven were classified as short-term (average duration: 12 weeks) of which two showed significant positive results. One of these studies evaluated an intervention in which print materials were sent to families,16 while the other (the only study in adolescents) encouraged mothers and adolescent daughters to exercise together.23 However, both were uncontrolled studies and the reliability of their results should be questioned. One of the two long-term interventions, a 3-year Finnish intervention in children aged 4 years at baseline, involving annual sessions with parents along with information posted out twice yearly,17 was found to be effective in increasing very active outdoor play in a CT. With a few exceptions, compliance and retention rates in the family-based interventions were found to be high overall. The authors concluded that “the evidence was not overwhelming” (page 1558) and argue a need for testing generalizability of interventions, sustainability of the effect and effective strategies for engaging families.

Three community-based interventions25 30 31 were reviewed by Salmon et al,8 all targeting children. They concluded that studies were limited by design issues (retrospective design or no true control condition), and low participation and response rates. One study, a retrospective cross-sectional evaluation of environmental changes to the area surrounding schools,31 showed a positive effect, whereas no overall effects were observed for the other two studies. Overall, the authors concluded that “further evidence of efficacy and sustainability of interventions promoting young people’s physical activity in the family and community settings is needed” (page 155).

Van Sluijs et al9 reviewed the available evidence up to December 2006, only including controlled studies and assessing methodological quality using a 10-item scale. A system of levels of evidence was used to form conclusions, whereby only those studies with the best available design and highest methodological quality within a category contributed to the conclusion. Conclusions were drawn separately for children and adolescents. Five family-based interventions13 15 17 18 20 were reviewed. Two involved educational sessions and information only while the remaining three additionally included activity sessions. Four were targeted at children with just one targeting adolescents. Based on the three highest quality studies in children and the one study in adolescents, none of which showed a significant positive effect, the authors concluded that there was no evidence for effect of family-based interventions in children and inconclusive evidence for effect in adolescents.9 The three community-based interventions14 26 27 were all classified as educational interventions, focusing on information provision and activity sessions. Two were delivered to scout groups; one targeting adolescent boys for nine weeks27 and the other primary school-aged girls over a period of two years.26 The remaining intervention was a pilot study targeting African-American 8-year old girls and delivering the intervention during a summer camp.14 None showed a significant positive effect leading to the conclusion of no evidence for effect of community-based interventions in children and inconclusive evidence for effect in adolescents.

Although the focus on methodological quality is a strength of the Van Sluijs et al9 review, it limited their potential to explore the strategies evaluated and the potential of intervention strategies used in studies with weaker designs. Based on their review of the evidence, the authors questioned the usefulness of “carrying out family-based… interventions, as most studies identified did not report positive results’ but also suggested that ‘it is necessary to identify and learn from the limitations of these interventions and their evaluations’”(page 10, web-paper9).

NICE10 reviewed the literature up to August 2007 and, similar to Salmon et al,8 the authors provided a narrative account of both controlled and uncontrolled studies, although additionally included a methodological quality rating for descriptive purposes (high, good or low quality). Eleven family-based interventions were included,13-16 18 19 21-24 32 33 the majority of which were conducted in children and four specifically targeted children who were (or were at risk of becoming) overweight or obese. These four studies were considered of good or high quality, and two reported positive results, both of which were conducted by the same research group. They involved similar intervention strategies targeting the whole family and including self-monitoring with pedometers.21 24 In their conclusion, the review authors highlighted that “characteristics of successful interventions [in overweight/obese children] included being located in the home… and focused on small, specific lifestyle changes.” (page 4010) In contrast, unsuccessful interventions required regular attendance at a site external to the home. Seven family-based interventions targeted young people regardless of weight status, three of which were of low quality and four showed positive changes (three studies of good and one of low quality). Two of these successful studies were small-scale interventions of female family members exercising together.22 23 One study was uncontrolled. Again, successful interventions were found to be located in the home and involving information packs, whereas less effective strategies required attendance of regular sessions outside the home.

The two community-based interventions27 34 included in the NICE review both targeted boys (due to the specific nature of this review, the results for the girls in one of the studies were included elsewhere35). One study, delivered to Boy Scout groups,27 was considered good quality. The second, low quality, study involved the provision of ‘Heart Health’ information, mainly in schools.34 Neither was able to show a significant positive intervention effect. However, the authors concluded that “there is no immediate or obvious reason why interventions in community groups such as boy scouts or church groups should not be successful and further research should be encouraged in this area” (page 7510).

In general, all reviews highlighted common methodological issues, including lack of long-term follow-up, poor validity of physical activity measures used, small study samples, and limited information on intervention fidelity and implementation. In addition, Salmon et al8 and Van Sluijs et al9 stressed the need to study mediators of change to better understand why an intervention did (or did not) work. Despite the observed lack of effectiveness, further high quality work was encouraged.

Update of evidence

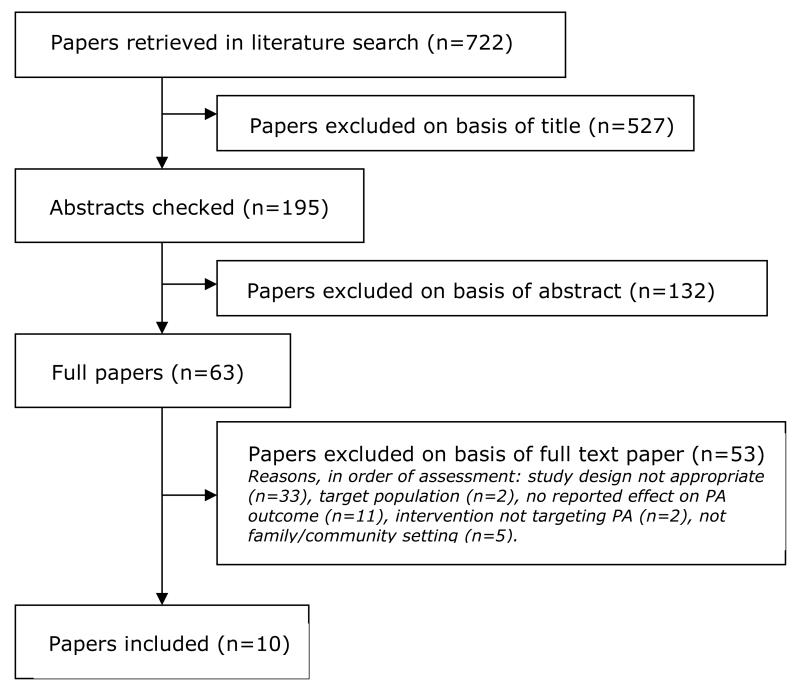

Figure 1 provides an overview of the flow of the literature search. A total of 10 studies were included, 9 RCTs, most of which were published in 2010 and included children rather than adolescents. Six studies were classified as family-based interventions,36-41 whereas the remaining four were community-based42-45 (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The methodological quality of the studies ranged from 2 to 10, with five studies classified as high quality (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 3). In general, randomisation procedures were described appropriately and most studies used intention-to-treat analyses. However, only four studies reported on the validity of the measure of physical activity and three had a follow-up after intervention completion of 6 months or longer.

Figure 1.

Identification of included studies in updated review (August 2007 to October 2010).

Table 2.

Summary of key characteristics of studies included in update review (shaded studies reported a significant positive effect on physical activity). For full description of studies, please see Supplementary Table 2.

| Ref | Target population | Intervention characteristics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Age | Sex | Ethnicity | Theory-based | Session types | Location | Target | Type1 | Duration | |

| Family-based interventions | ||||||||||

| Chen ‘1036 | All | 8-10 yr | Both | Chinese American |

SCT | Group, P/C separately |

Outside home |

PA & diet |

C: EDU + EXE P: EDU |

2M |

| Hovell ‘0937 | All | 10-13 yr |

Both | - | - | Group, P/C separately |

Outside home |

PA & diet |

C: EDU + EXE P: EDU |

2M |

| Morgan ‘1038 | All | 5-12 yr | Both | - | SCT/FST | Group, P/C together and separately |

Outside home |

PA & diet |

EDU + EXE | 3M |

| Reinehr ‘1039 | OV only | 8-16 yr | Both | - | Systemic & solution-focused theories |

Group, P/C together and separately |

Outside home |

PA & diet |

C: EDU + EXE P: EDU |

6M |

| Sacher ‘1040 | OB only | 8-12 yr | Both | - | Learning and SC theories |

Group, P/C together | Outside home |

PA & diet |

C: EDU + EXE P: EDU |

6M |

| Shelton ‘0741 | OV/OB only |

3-10 yr | Both | - | - | Group, P only | Outside home |

PA & diet |

EDU | 1M |

| Community-based interventions | ||||||||||

| Black ‘1042 | All | 11-16 yr |

Both | Non- Hispanic black African- American |

SCT/MI | Mentor, 1-1 with C, P present |

At home | PA & diet |

EDU + EXE | 11M |

| Farley ‘0743 | All | 7-14 yr | Both | - | N/A | N/A – Playground made available |

Outside home |

PA | ENV | 2yr |

| Haire-Joshu ‘1044 |

All | 5-12 yr | Both | - | SCT | Mentor, 1-1 with C, info for P |

Outside home |

PA & diet |

EDU | ~6M |

| Rosenkranz ‘1045 |

All | 9-13 yr | Girls | - | SCT | Group (C only) | Outside home |

PA & diet |

EDU + EXE | 6M |

Abbreviations: Ref: Reference; OV: overweight; OB: obese; SCT: Social-Cognitive Theory; FST: Family Systems Theory; MI: Motivational Interviewing; P: Parent; C: Child; yr: year; PA: physical activity; M: month.

Type of intervention categorised as: ENV (environmental) - changes to policy or physical environment; EDU (educational) - including giving information, working with participants to set goals, etc; EXE (exercise) – providing exercise sessions.

Table 3.

Key methodological indicators of studies included in updated review (shaded studies reported a significant positive effect on physical activity)

| Ref | Methodological quality (0-10) |

Design | Physical activity measure | Adherence to intervention1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family-based interventions | ||||

| Chen ‘0936 | 9 | RCT | Accelerometer | No information provided |

| Hovell ‘1037 | 6 | RCT | CR 24-hour recall | 75% had high attendance |

| Morgan ‘1038 | 5 | RCT | Pedometer | Participants attended 81% of sessions |

| Reinehr ‘1039 | 6 | RCT | CR questionnaire | All families (except one) had high attendance |

| Sacher ‘1040 | 5 | RCT | CR+PR questionnaire | High for 9-wk sessions (mean attendance 86%), low for 12-wk swim pass (32% of families used this) |

| Shelton ‘0741 | 4 | RCT | PR Diary | No information provided |

| Community-based interventions | ||||

| Black ‘1042 | 10 | RCT | Accelerometer | 52% had high attendance |

| Farley ‘0743 | 2 | CT | Direct observation | Popular upon opening, higher attendance when school was in session |

| Haire-Joshu ‘1044 | 5 | RCT | PR questionnaire | 82% had high attendance |

| Rosenkranz ‘1045 | 8 | RCT | CR questionnaire (accelerometer for during intervention sessions) |

High implementation and high attendance |

Abbreviations: Ref: reference; CR: Child-report; PR: Parent-report; wk: week.

High attendance defined as attending all or most of the sessions offered. The information provided varies according to what was provided in the original papers.

Effect on physical activity

Three of the six family-based interventions reported a significant positive effect on physical activity.36 38 40 One was a high quality RCT of an 8-month intervention based on social cognitive theory in which the children attended 8 weekly 45-minute sessions and the parents attended two 2-hour workshops.36 The other two were low quality RCTs, targeted at overweight fathers and their children38 and at families of obese children, respectively.40 No consistent differences in terms of intervention (such as theoretical basis), target population or methodology could be identified between the effective and ineffective interventions (see Tables 2 and 3).

One of the four community-based interventions, a low quality CT of an environmental intervention,43 reported a significant positive effect on a physical activity-related outcome measure. In this study, the playground of a local primary school was made available during out-of-school hours (including weekends) and supervision was provided during these periods. The three other interventions, including two mentoring schemes42 44 and an intervention targeting female scouts,45 were ineffective in increasing overall activity. The latter intervention was shown to significantly increase objectively-measured physical activity during the troop meetings, but no intervention effect was observed for overall, self-reported, physical activity.

Effect on secondary outcomes

Five of the six family-based interventions reported on changes in anthropometry.36 38-41 Only one did not report a significant effect on anthropometry,38 despite a reported effect on physical activity. In addition, one study reported a significant decrease in BMI in the intervention group and a significant increase in the control group, but no between group tests were conducted.39 The only study reporting on a fitness-related outcome measure, heart-rate recovery, reported a significant positive effect.40 Interestingly, interventions targeted at overweight or obese populations were more likely to report positive effects on anthropometry, irrespective of the effect on physical activity levels.

All studies evaluating community-based interventions reported on anthropometry outcomes. Only one, a home-based mentoring scheme, reported a significant positive effect.42 No study reported on a fitness-related outcome.

DISCUSSION

Physical activity promotion in young people is currently a key public health strategy. Schools are often the preferred setting for these initiatives, not least because young people spend many hours at school and it provides researchers with a captive population. Nonetheless, considering the variety of influences on young people’s behaviours, interventions in other settings should also be considered. The aim of this paper was to present an overview of the effectiveness of family- and community-based physical activity interventions using a mixed-methods review strategy. Previous reviews of the literature highlighted the paucity of evidence in this area, especially from community-based interventions, and the limited methodological quality of the studies. The updated review of the evidence shows important progress, with an additional 10 controlled studies published since August 2007, which were generally found to be of higher methodological quality than previous work. However, there remains a lack of (good quality) evaluations of community-based interventions and identifying the components of family-based interventions associated with effectiveness proved challenging. This was also highlighted by a previous review studying how to engage parents to increase youth physical activity,46 where they concluded that no obvious pattern could be identified. However, they suggested that a medium-to-low level engagement, such as parent training, family counselling or telephone-based interventions, as opposed to actually engaging parents in a family physical activity programme with their children, may be effective.

In the updated review, three of the six family-based studies reported significant positive effects, such as 2327 more steps per day38 or 3.9hr of additional physical activity per week.40 However, comparisons of the interventions, target populations or evaluation methods did not identify common components across the effective and ineffective interventions. As in the previous reviews, most studies targeted children, which may be a reflection of the perception that families become less of an influence throughout adolescence. Neither of the two studies including adolescents, a community-based mentoring scheme42 and family-based educational intervention,39 showed a positive effect. Only one community-based intervention43 was shown to be effective, which was the only environmental intervention and the only intervention solely targeting physical activity. On the other hand, the evaluation of this intervention, where the school playground was made available during out-of-school hours, had a low methodological quality score raising doubts about the validity of the conclusions. The earlier reviews tentatively showed that family-based interventions may be more likely to be effective if they are set in the home and include self-monitoring (using pedometers) and goal setting for specific lifestyle changes (such as increasing baseline steps by 2000 steps per day). These strategies, however, were not replicated in more recent research. Instead, most interventions focused on provision of information in group settings, as well as activity sessions for the children. Although a few studies included elements of self-monitoring, these were only minor intervention components and unlikely to have made substantial contributions to a potential intervention effect. Self-monitoring with pedometers can be effective in increasing physical activity levels in both adults and young people, especially when combined with goal setting.47 48 However, the few pedometer-based studies conducted in young people to date have tended to be set in schools and of medium to low methodological quality.48 A recent review of behaviour change strategies in family-based childhood obesity prevention interventions also highlighted ‘prompting specific goal setting’, ‘prompting self-monitoring’, ‘setting graded tasks’ and ‘providing performance feedback’ as common components of effective interventions.49 Based on the previously identified potential of these strategies, it is important that their applicability in the family- or community-setting is further explored and tested, using high quality research with longer-term follow-up.

Intervention implementation is known to affect outcomes50 and eight different aspects of implementation can be identified: fidelity, dosage, quality, participant responsiveness, program differentiation, monitoring of control condition, programme reach and adaptation. Few of the studies included in this review reported on attempts to assess aspects of implementation beyond attendance rates. Where reported in the family-based interventions,37-40 attendance was generally found to be high, despite none of them being delivered in the home. The required attendance of both children and parents at locations outside the home has previously been suggested to affect compliance,10 but this does not appear to have been the case in the more recent studies. Intervention delivery in general was poorly described, and only one study45 reported on the quality of implementation of the intervention, as assessed by the intervention deliverers. One area of concern in this literature is the reach of the intervention programme. Studies often reported using wide-ranging recruitment methods, with the potential to reach a large population, such as media campaigns, brochures and flyers. However, no study reported on their recruitment rates compared to those eligible or invited to participate or on representativeness of their study sample to the target study population, raising questions regarding the generalizibility of the results to wider populations and the potential for wider implementation.

Previous reviews have highlighted the potential of environmental interventions both in- and outside the school setting.8 9 Most of these interventions aim to create safe opportunities for active play or travel. The only environmental intervention included in our updated review also elicited significant positive effects.43 Two recent reviews also showed that after-school programmes can be effective in promoting children’s physical activity.51 52 These programmes generally also include the provision of safe and accessible opportunities for physical activity, next to health education. A small but growing body of evidence therefore seems to indicate that increasing safe opportunities for children to engage in play-based activities both during and out-of-school may be a worthwhile strategy to pursue. Nonetheless, the reported results must be interpreted cautiously as most studies used small sample sizes and were of poor quality, affecting the internal validity of the studies and the reliability of the conclusions drawn. The evaluation of environmental interventions or other natural experiments potentially affecting physical activity or other health behaviours is known to be challenging and fraught with difficulties.53 54 It is however crucial for future decision-making that these collective interventions are evaluated with appropriate study designs and robust measures of the outcome to better estimate their effectiveness and allow for comparisons with other approaches.53

Several studies reported positive effects on anthropometry outcomes. Those studies that targeted overweight or obese participants were more likely to report significant positive effects, irrespective of the reported effect on physical activity. This is likely to be predominantly explained by the greater potential to obtain an effect on body composition among these participants than in the general population. Nevertheless, several other issues may have contributed to this finding. Body composition can be measured more precisely and with less error than physical activity.55 Indeed, for many studies body composition was the main outcome measure and the sample size will have been determined accordingly. In addition, the interventions targeted both dietary and physical activity behaviour and two of the studies targeting overweight or obese participants reported significant positive outcomes for dietary behaviour, but not for physical activity39 41 (the remaining study did not report on a dietary outcome40). It may be that for overweight or obese populations improvements in dietary behaviour are – at least initially - more important to obtain improvements in body composition, although no mediation analyses were presented for the studies included in this review. However, it is likely that for weight maintenance, improvements in both physical activity and dietary habits are necessary. Moreover, it is important to stress that physical activity has important health benefits independent from weight.1 56

Although the methodological quality of the more recently conducted evaluations appears to have improved, several challenges still remain. Only three of the ten studies in the updated review used an objective measure of physical activity and only four reported on the validity of their physical activity measure. We found that the type of physical activity measure used was not related to intervention effectiveness. However, increasing the precision of the measurement of physical activity as well as studying how changes occur across the week and in different domains will allow for a more thorough investigation of the effects of interventions. Only three studies reported a follow-up of six months or longer, with one reporting a significant positive intervention effect. The long term effect of family- and community-based interventions therefore also remains unclear. Indeed, previous literature appears to suggest that repeated intervention efforts may be necessary in order to obtain established changes in physical activity habits.57 Few studies investigating physical activity promotion in young people have investigated mediation of the intervention effect58 and to our knowledge none of the studies in the updated review reported on mediation effects. Studying mediation is an important strategy in order to develop an understanding of effective intervention elements and the mechanisms of change and it is recommended that future evaluations include measures along the causal pathway in order to study this.

As with the primary studies, this review has its strengths and limitations. We conducted a systematic literature search, assessed final study inclusion and methodological quality by two reviewers independently, assessed methodological quality and systematically investigated potential common components of effective interventions. Limitations include the restriction of the literature search to three databases, only one reviewer undertaking the initial reviewing stages, and the potential for publication bias. However, we aimed to minimize the affect of the former two issues by selecting the three key databases based upon previous review experience9 and by using broad initial review criteria. We based our quality assessment on the published evidence rather than contacting all the primary authors to allow us to both study the quality of the studies and highlight continuing issues with the reporting of trials.

CONCLUSION

Using a mixed-method review strategy, this paper shows that findings for the effectiveness of family- and community-based interventions remains uncertain, especially among adolescent populations. The limited evidence available comes from interventions targeted at families and set in the home. The efficacy and sustainability of environmental interventions and interventions including self-monitoring using pedometers outside of the school setting should be investigated further with high quality evaluations and longer follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Search strategy for updated review (August 2007 to October 2010)

Supplementary Table 2: Characteristics and results of studies included in updated review

Supplementary Table 3. Quality assessment for each study included in the updated review (studies presented in alphabetical order within setting).

Acknowledgments

FUNDING The work of EvS was supported by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Department of Health, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen LB, Harro M, Sardinha LB, et al. Physical activity and clustered cardiovascular risk in children: a cross-sectional study (The European Youth Heart Study) Lancet. 2006;368:299–304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nader PR, Bradley RH, Houts RM, et al. Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity From Ages 9 to 15 Years. JAMA. 2008;300:295–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almond L, Harris J. Interventions to promote health-related physical education. In: Biddle S, Sallis J, Cavill N, editors. Young and Active? Young people and health-enhancing physical activity - evidence and implications. Health Education Authority; London: 1998. pp. 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward DS, Saunders RP, Pate RR. The role of theory in understanding physical activity behavior. In: Ward DS, Saunders RP, Pate RR, editors. Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents. Human Kinetics; Champaign: 2007. pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Promoting better health for young people through physical activity and sport. US Secretary of Health and Human Services & US Secretary of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choosing Activity: a physical activity action plan. Department of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salmon J, Booth ML, Phongsavan P, et al. Promoting physical activity participation among children and adolescents. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007;29:144–159. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Sluijs EMF, McMinn AM, Griffin SJ. Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. BMJ. 2007;335(7622):703–707. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39320.843947.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NICE Public Health Collaborating Centre - Physical Activity Physical activity and children: Review 7 - Intervention review: family and community. 2008.

- 11.Kriemler S, Meyer U, Martin E, et al. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. Br J Sports Med. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson TN, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, et al. Dance and reducing television viewing to prevent weight gain in African-American girls: the Standford GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:S65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baranowski T, Simons-Morton B, Hooks P, et al. A center-based program for exercise change among black-American families. Health Educ Q. 1990;17:179–196. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Cullen KW, et al. The Fun, Food, and Fitness Project (FFFP): The Baylor GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:S30–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beech BM, Klesges RC, McClanahan B, et al. Child- and parent-targeted interventions: The Memphis GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:S40–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cookson S, Heath A, Bertrand L. The HeartSmart Family Fun Pack: an evaluation of family-based intervention for cardiovascular risk reduction in children. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:256–259. doi: 10.1007/BF03404283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saakslahti A, Numminen P, Salo P, et al. Effects of a three-year intervention on children’s physical activity from age 4 to 7. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2004;16:167–180. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nader PR, Sallis JF, Abramson IS, et al. Family-based cardiovascular risk reduction education among Mexican and Anglo-Americans. Fam Community Health. 1992;15:57–58. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ransdell LB, Dratt J, Kennedy C, et al. Daughters and mothers exercising together (DAMET): a 12-week pilot project designed to improve physical self-perception and increase recreational physical activity. Women Health. 2001;33:101–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey-Berino J, Rourke J. Obesity prevention in preschool Native-American children: A pilot study using home visiting. Obes Res. 2003;11:606–611. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Stroebele N, et al. Small changes in dietary sugar and physical activity as an approach to preventing excessive weight gain: the America on the Move family study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e869–79. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ransdell LB, Robertson L, Ornes L, et al. Generations Exercising Together to Improve Fitness (GET FIT): a pilot study designed to increase physical activity and improve health-related fitness in three generations of women. Women Health. 2004;40:77–94. doi: 10.1300/j013v40n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ransdell LB, Taylor A, Oakland D, et al. Daughters and mothers exercising together: effects of home- and community-based programs. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:286–296. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048836.67270.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Barry MJ, et al. A family-based approach to preventing excessive weight gain. Obesity. 2006;14:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huhman M, Potter LD, Wong FL, et al. Effects of a mass media campaign to increase physical activity among children: Year-1 results of the VERB campaign. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e277–e284. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.French SA, Story M, Fulkerson JA, et al. Increasing weight-bearing physical activity and calcium-rich foods to promote bone mass gains among 9-11 years old girls: Outcomes of the Cal-Girls study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, et al. Fit for Life Boy Scout badge: Outcome evaluation of a troop and Internet intervention. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Story M, Sherwood NE, Himes JH, et al. An after-school obesity prevention program for African-American girls: the Minnesota GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:S54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nader PR, Sallis JF, Patterson TL, et al. A family approach to cardiovascular risk reduction: results from the San Diego Family Health Project. Health Educ Q. 1989;16:229–244. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pate RR, Saunders RP, Ward DS, et al. Evaluation of a community-based intervention to promote physical activity in youth: lessons from Active Winners. Am J Health Promot. 2003;17:171–82. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.3.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boarnet MG, Anderson CL, Day K, et al. Evaluation of the California Safe Routes to School legislation: urban form changes and children’s active transportation to school. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ransdell LB, Detling NJ, Taylor A, et al. Effects of home- and university-based programs on physical self-perception in mothers and daughters. Women Health. 2004;39:63–81. doi: 10.1300/J013v39n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salminen M, Vahlberg T, Ojanlatva A, et al. Effects of a controlled family-baesd health education/counselling intervention. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29:395–406. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.5.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baxter AP, Milner PC, Hawkins SS, et al. The impact of heart health promotion on coronary heart disease lifestyle risk factors in schoolchildren: lessons learnt from a community-based project. Public Health. 1997;111:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NICE Public Health Collaborating Centre - Physical Activity Promoting physical activity for children: review 6 - interventions for adolescent girls. 2009.

- 36.Chen J-L, Weiss S, Heyman MB, et al. Efficacy of a child-centred and family-based program in promoting healthy weight and healthy behaviors in Chinese American children: a randomized controlled study. J Public Health. 2010;32:219–229. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hovell MF, Nichols JF, Irvin VL, et al. Parent/Child training to increase preteens’ calcium, physical activity, and bone density: a controlled trial. Am J Health Promot. 2009;24:118–28. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.08021111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan PJ, Lubans DR, Callister R, et al. The ‘Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids’ randomized controlled trial: efficacy of a healthy lifestyle program for overweight fathers and their children. International Journal of Obesity. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinehr T, Schaefer A, Winkel K, et al. An effective lifestyle intervention in overweight children: findings from a randomized controlled trial on “Obeldicks light”. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:331–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sacher PM, Kolotourou M, Chadwick PM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the MEND program: a family-based community intervention for childhood obesity. Obesity. 2010;18:S62–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shelton D, Le Gros K, Norton L, et al. Randomised controlled trial: A parent-based group education programme for overweight children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:799–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Black MM, Hager ER, Le K, et al. Challenge Health promotion/obesity prevention mentorship model among urban, black adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126:280–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farley TA, Meriwether RA, Baker ET, et al. Safe play spaces to promote physical activity in inner-city children: results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1625–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haire-Joshu D, Nanney MS, Elliott M, et al. The use of mentoring programs to improve energy balance behaviors in high-risk children. Obesity. 2010;18:S75–83. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenkranz RR, Behrens TK, Dzewaltowski DA. A group-randomized controlled trial for health promotion in Girl Scouts: Healthier Troops in a SNAP (Scouting Nutrition & Activity Program) BMC Public Health. 2010;10:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Connor TM, Jago R, Baranowski T. Engaging parents to increase youth physical activity a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, et al. Using Pedometers to Increase Physical Activity and Improve Health: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2007;298:2296–2304. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Tudor-Locke C. A systematic review of studies using pedometers to promote physical activity among youth. Prev Med. 2009;48:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Golley RK, Hendrie GA, Slater A, et al. Interventions that involve parents to improve children’s weight-related nutrition intake and activity patterns - what nutrition and activity targets and behaviour change techniques are associated with intervention effectiveness? Obes Rev. 2011;12:114–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:327–50. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beets MW, Beighle A, Erwin HE, et al. After-school program impact on physical activity and fitness: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pate RR, O’Neill JR. After-school interventions to increase physical activity among youth. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:14–18. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.055517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ogilvie D, Griffin S, Jones A, et al. Commuting and health in Cambridge: a study of a ‘natural experiment’ in the provision of new transport infrastructure. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:703. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.NICE . Promoting and creating built or natural environments that encourage and support physical activity. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wareham NJ, van Sluijs EMF, Ekelund U. Physical activity and obesity prevention: a review of the current evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:229–247. doi: 10.1079/pns2005423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ekelund U, Anderssen SA, Froberg K, et al. Independent associations of physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness with metabolic risk factors in children: the European youth heart study. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1832–40. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0762-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Sluijs EMF, McMinn AM. Preventing obesity in primary schoolchildren. BMJ. 2010;340:c819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lubans DR, Foster C, Biddle SJH. A review of mediators of behavior in interventions to promote physical activity among children and adolescents. Prev Med. 2008;47:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Search strategy for updated review (August 2007 to October 2010)

Supplementary Table 2: Characteristics and results of studies included in updated review

Supplementary Table 3. Quality assessment for each study included in the updated review (studies presented in alphabetical order within setting).