Abstract

A 47-year-old woman with a history of intravenous drug use presented to the emergency department with a 6-month history of pain in her lumbar back and right buttock. She had stopped injecting drugs 1 year ago. Physical examination was unremarkable except for paraspinal and right sacroiliac joint tenderness. MRI confirmed discitis, osteomyelitis and abscess formation in the L5–S1 disc space. She underwent extensive vertebral surgery and debridement of the spinal abscess. Her surgical cultures grew Mycobacterium fortuitum, and she was treated with an appropriate combination of intravenous antimicrobial therapy.

Background

Mycobacterium fortuitum is a rapidly growing non-tuberculous mycobacterium (NTM). This organism is ubiquitous, populating dirt and both natural and processed water sources worldwide. It is also found in animals, although zoonotic transmission is not a threat to humans.1 M fortuitum is typically considered to be a contaminant, causing nosocomial infections that have been associated with catheters, breast implants and prosthetic joint devices. Human-to-human transmission is unusual; it spreads haematogenously or via direct invasion. M fortuitum may infect immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Clinical manifestations include pneumonia, superficial lymphadenitis and infections of skin, soft tissue or bone. It may also cause disseminated infection, most often in patients with AIDS.2 M fortuitum and other rapidly growing NTM do not always reliably stain with the “acid-fast” (Ziehl-Neelsen) method. Culture on solid media is the most specific technique to identify M fortuitum. As “rapidly-growing” NTM, growth should be apparent within 1 week. M fortuitum is the most common rapidly growing NTM seen in clinical labs. NTM cases are not mandatorily reported to the Centres for Diseases control and Prevention, so precise incidence and prevalence is unknown. However, there are estimated to be between 4 and6 cases/1 000 000 people in USA annually.3

Case presentation

History of present illness

A 47-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of intravenous drug use (IVDU) presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of progressively worsening pain in her lumbar back and right buttock. She denied previous history of back pain, trauma or any inciting event. Her medical history was significant only for lower extremity cellulitis, a year prior. Her surgical history included cholecystectomy, tubal ligation and multiple incision and drainages for skin abscesses. She received epidural injections during the birth of her two children 17 and 19 years ago but never had back surgery or other epidural treatment. She was not taking any medications regularly. Social history was positive for IVDU, but she adamantly denied injecting during the past year, and is involved with a support group. She had a 30 pack-year smoking history, and works as a licensed tattoo artist.

Physical examination

On arrival, she was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 140/96, heart rate 104 bpm and respiratory rate 20 breaths/min. Physical examination was unremarkable except for tenderness in her paraspinal region and right sacroiliac joint. She was discharged home with a diagnosis of back pain and the ED physician prescribed prednisone, tramadol/acetominophen and cyclobenzaprine.

However, her pain continued to worsen and she returned to the ED 5 days later with sharp, excruciating pain in her lower back radiating to her right leg. Her pain was exacerbated by movement, especially bending, twisting and walking. She also reported numbness and weakness in her right lower extremity, but had no other neurological deficits. She denied nausea, vomiting, fevers, chills, night sweats, saddle anaesthesia or loss of bladder or bowel function.

In the ED, her blood pressure was 140/97, heart rate 117 bpm, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min, temperature 37°C and she was saturating well on room air. On physical examination, her lumbosacral spine and right gluteal region were exquisitely tender to palpation. Range of motion in her right hip and back elicited severe pain. Of note, there were multiple track marks on her neck and all extremities from prior IVDU. Her neurological examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

Laboratory

Complete blood count, blood chemistry and urinalysis all within normal limits. Blood cultures were negative. The hepatitis panel and HIV test were also negative. Serological studies revealed an elevated C reactive protein (CRP) of 2 and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40.

Imaging

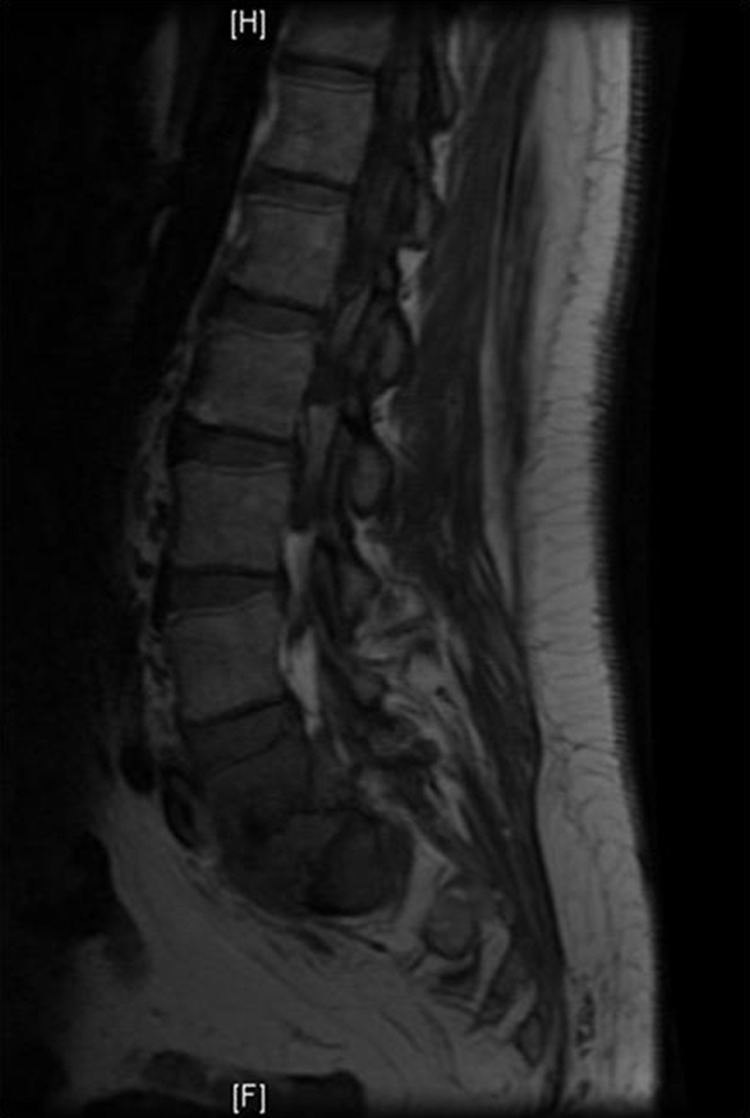

An X-ray of the pelvis was normal except for mild sclerotic changes at L5–S1. CT scan of the lumbar spine showed probable discitis and osteomyelitis with perivertebral inflammatory changes at L5–S1. Subsequent MRI displayed enhancing abnormalities in the L5–S1 disc space, confirming discitis, osteomyelitis and abscess formation (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preoperative MRI showing enhancing abnormalities in the L5–S1 disc space confirming discitis, osteomyelitis and abscess formation.

Treatment

The patient was admitted and a central line was placed due to poor peripheral access from prior IVDU. Cefepime and vancomycin were started empirically and narcotics were given for pain control. Her back and leg pain became intolerable over the course of 24 h, making it difficult to ambulate.

On hospital day 2 she underwent laminectomies with medial facetectomies and discectomies for nerve root decompression in L5 and S1. The L5–S1 disc space was exenterated for debridement of the spinal abscess and fused using iliac crest autograph and instrumentation (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Postoperative MRI showing spinal osteomyelitis showing resolution of vertebral abscess.

Routine cultures from the epidural abscess initially showed no organisms on Gram stain and no anaerobic growth, but M fortuitum was later identified from the surgical specimen.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient remained hospitalised for two additional weeks while she recuperated and received amikacin and cefoxitin intravenously. On discharge, she has been followed by infectious disease for outpatient antibiotic therapy with TMP/SMX and doxycycline.

Discussion

Assuming that this patient did not inject drugs for the past year, we speculate that her spinal infection originated from a transient bacteraemia which she contracted many months earlier during her previous IVDU. We postulate that this transient bacteraemia seeded in the patient's lumbar spine and subsequently developed her abscess. There is a similar report of an HIV-negative intravenous drug user who developed M fortuitum bacteraemia and endocarditis from injecting heroin mixed with tap water.4 In contrast, the patient in this case injected heroin daily, so the time frame between injection of contaminated water and development of infection was unknown. Our case suggests that M fortuitum can cause potentially insidious infection in former intravenous drug users as well as those who are actively injecting. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of atypical NTM infections in patients with a history of IVDU.

Vertebral osteomyelitis caused by M fortuitum is extremely rare; a MEDLINE literature review of cases from 1965to 2003 reported merely 31 cases of spinal osteomyelitis caused by NTM, and only five of these were from M fortuitum.5 A more recent study cited only 38 cases of NTM vertebral osteomyelitis in HIV-negative patients reported in the literature from 1956to 2011.6 Because NTM spinal osteomyelitis infections are so infrequent, there are no guidelines for treatment.

M fortuitum is resistant to traditional antituberculous drugs (rifampin, isoniazid and ethambutol), and infections should be treated with at least two antimicrobial drugs to prevent resistance from developing. An initial regimen should include oral and parental antibiotics for 4–6 weeks. Suggested combinations include TMP/SMX, doxycycline, or a fluoroquinolone by mouth, plus amikacin, imipenem or cefoxitin intravenously. When the patient improves clinically, antibiotic therapy can be switched to two or three oral agents and should be continued for at least a total of 6 months.2

Less than one of three cases of NTM vertebral osteomyelitis caused by NTM are diagnosed in the first month following onset of symptoms. Serological studies may show leucocytosis and increased non-specific inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP). Blood cultures are rarely positive, making early diagnosis a challenge. Consequently, a biopsy is crucial in diagnosing infection caused by NTM. Surgery is also important in treating NTM spinal osteomyelitis, especially if there is widespread local involvement or abscess formation. However, there are no studies or guidelines concerning surgical debridement for this rare infection, so these cases are best managed by experienced clinicians.

Learning points.

Non-tuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) can cause potentially insidious infection in former intravenous drug users as well as those who are actively injecting.

Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of atypical NTM infections in patients with a history of intravenous drug use.

Urgent surgical intervention with adequate culture for mycobacterium should be performed in order to guide antimicrobial treatment for abscesses.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bercovier H, Vincent V. Mycobacterial infections in domestic and wild animals due to Mycobacterium marinum. M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. porcinum, M. farcinogenes, M. smegmatis, M. scrofulaceum, M. xenopi, M. kansasii, M. simiae and M. genavense. Rev Sci Tech 2001;2013:265–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;2013:367–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler W, Crawford J, Shutt K. Nontuberculous mycobacteria reported to the Public Health Laboratory Information System by state public health laboratories, United States, 1993–1996. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Natsag J, Min Z, Hamad Y, et al. A mysterious gram-positive rods. Case Rep Infect Dis 2012;2013:841834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petitjean G, Fluckiger U, Schären S, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect 2004;2013:951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu H, Mizuno Y, Nakamura I, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria: case reports and review. J Infect Chemother. Published Online First: 22 Jan 2013. doi:10.1007/s10156-013-0550-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]