Abstract

Background

Accurate staging is critical for determining treatment for prostate cancer. Our objective was to examine whether race or age disparities affected the odds of being staged among prostate cancer patients.

Methods

Multivariable logistic regression models examined race and age disparities with respect to the odds of being staged among prostate cancer patients using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data. Similar analyses were performed to estimate the adjusted odds of being staged with distant metastatic versus in situ or local/regional disease.

Results

The proportion of patients without staging ranged between 3% – 16% by age and 6% – 8% by race. Adjusted results demonstrated statistically significant lower odds (p < 0.05) for 70–74, 75–79, and 80+ year olds of 0.76, 0.52, and 0.23, respectively, relative to prostate cancer patients ages 65–69. The odds of being staged for African Americans are 0.78 times that of non-Hispanic Whites (95% CI = 0.72 – 0.86). The adjusted probability of distant metastatic disease at initial diagnosis is higher for African Americans (OR = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.47 – 1.76) and older men with ORs of 1.25, 1.85 and 4.33 for ages 70–74, 75–79 and 80+, respectively, compared to 65–69 year olds (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Even though the overall odds of being staged increased over time, race and age disparities persisted. When staging did occur, the probability of distant metastatic disease was high for African-Americans and there were increasing odds of metastatic disease for all men with advanced age.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, staging, SEER-Medicare, health disparities, African American

BACKGROUND

It is well documented that African-American (AA) men with prostate cancer (PC) have more advanced disease and poorer prognosis than their White counterparts.1–14 For instance, AA patients with localized PC experience shorter disease-free survival than other racial groups.1 Multiple factors including socioeconomic status (SES) and behaviors contribute to higher PC incidence and mortality among AA men.2 However, racial disparities persist even after controlling for SES.3 AA men not only have higher PC incidence and mortality, but also PC may be more aggressive in AA men than European-American men, particularly at younger ages.4

While racial/ethnic and age disparities in PC survival may partially be explained by biology, disparities in screening and treatment also contribute to the observed differences in disease outcomes. Godley et al reported greater disparities in survival rates between AA and White men ages 65–84 with localized PC who were treated with surgery compared to those treated with radiation therapy or treated non-aggressively (i.e. no surgery or radiation therapy).5 Byers et al found that AA men were less likely to receive relatively more expensive or innovative treatments.3

Lack of awareness of treatment options and lack of patient education by physicians can affect access to health care. Tewari et al suggested that AA men tend to be less informed of their options compared to Whites, and therefore may not seek aggressive treatment options for clinically localized PC.6 Klabunde et al noted that AA men with locally advanced PC are less likely to undergo radical prostatectomy than their White counterparts; however, race was not a factor when comparing access to radiation therapy.7

The main objective of this study was to examine the evidence for race or age disparities in PC staging. While prior reports provide evidence of more advanced PC among older men and AA men, this is the first study to examine whether there are disparities in the likelihood of being staged among PC patients.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

This cross-sectional study utilized a merged dataset of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and Medicare databases available through a collaborative project of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Data for PC patients diagnosed in 1998 through 2002 with claims from the year prior to diagnosis through 2003 were used.

The information on cancer incidence and survival collected by the SEER program comes from population-based cancer registries covering approximately 26 percent of the US population. The SEER-Medicare database represents a subset of the SEER population, which is created by merging the SEER data of cancer patients eligible for Medicare with their claims for covered health care services under Medicare. The available claims span the period from the time of Medicare eligibility until death. The current study included data from the following registries: San Francisco, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta, San Jose, Los Angeles, Rural Georgia, Greater California, Kentucky, Louisiana, and New Jersey.

Study Subjects

Of 180,861 Medicare patients diagnosed with PC between 1997 and 2002, we excluded 1,179 patients with unknown month of diagnosis and 1 person with unknown age at diagnosis. Since the current study focused on disparities among the elderly, 33,870 patients younger than 65 (Medicare eligible due to disability) at time of diagnosis were removed. We further narrowed our sample by excluding 11,137 men of races other than non-Hispanic White (non-HW), AA, and White Hispanic (WH) and 14,900 patients diagnosed in 1997 because SEER did not start collecting PSA test results until January 1, 1998. Finally, 5,612 subjects were deleted because of missing Census Tract information. Thus, the final study cohort was 114,162 men with one unique episode per patient.

Data Analysis

We used univariate descriptive analyses to find the overall distribution of race and age in our cohort. Using descriptive bivariate analyses, we compared the various sociodemographic characteristics between White and AA patients. We looked at racial differences in several clinical and treatment variables such as stage of disease and whether or not a PSA test was done in the period preceding diagnosis. Bivariate association between categorical variables was measured using the Pearson chi-square test for independence.

The final stage of our analysis consisted of building the appropriate multivariable logistic models to measure race and age disparities in PC staging by controlling for year of diagnosis, marital status, urban/rural living area, state buy-in (low income), whether or not a PSA test was done in the period preceding diagnosis, census tract median household income by race, and SEER cancer registry. The first model predicted the probability of being staged and the second predicted the probability of being staged with distant metastatic versus in-situ or local/regional disease. The second model was run only in the subset of staged patients.

We examined two additional models that included interaction terms of race and age each with year of diagnosis. The use of interaction terms allows for a statistical test of trends in race or age disparities over time.

The model building process included sensitivity analyses that evaluated the impact of adding or excluding covariates, or the impact of changing the way certain categorical variables were defined. Model diagnostics tests included the Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test15 and the regression error specification test (RESET) developed by Sunil Sapra.16

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables were computed from the SEER historic stage variable, which is assigned by SEER after all clinical and pathological documentation of the extent of disease is examined. SEER uses the cancer extent of disease (EOD) classification system as its primary staging system, which is subsequently translated into AJCC summary and historical staging. The EOD scheme includes separate fields for tumor size, extension of primary tumor, involvement of lymph nodes, number of positive regional lymph nodes, and number of examined regional lymph nodes. In the current study, we used the SEER historic stage variable, which was produced by the cancer registry using an algorithm developed by the End Results Group of the NCI. The algorithm collapses the detailed extent of disease information into the in-situ, local, regional, and distant categories. The dependent variable in the full sample analysis was a binary measure examining whether a PC patient had been staged (1 if yes; 0 otherwise). The outcome for the subgroup analysis was also a binary measure that examined whether a patient’s stage was distant (1 if yes; 0 otherwise) versus in-situ or local/regional. Unstaged patients were excluded from the secondary analyses.

Covariates

The covariates of interest were race, age and year of diagnosis. Non-HW and 65–69 year old patients were the reference groups against which AA and WH and elderly PC patients were measured. Other covariates included: marital status; urban/rural living area; state buy-in coverage in the year prior to diagnosis (proxy for low income); whether or not a PSA test was performed in the period preceding diagnosis; census tract median household income by race; and a series of geographic indicators that identified which of the 16 cancer registries patients belonged to. We categorized patients as having received a PSA test when the tumor marker 2 variable in SEER was coded as ‘positive’, ‘negative’, ‘borderline’ or 'ordered but results not in chart'. Alternately, when it was coded as ‘none done’ or ‘unknown’ we categorized patients as not having received a PSA test. The continuous median household income measure was divided by 10,000 and mean-centered to facilitate interpretation of the results. The process of mean-centering consists of finding the average median household income across all patients, and then subtracting each individual observation from the population average. The resulting mean-centered value provides information on the difference between the patients’ census tract median household income and the population average.

RESULTS

The racial/ethnic composition of our sample cohort was 82% non-HW, 11% AA and 7% WH. In addition, 30% of all patients were diagnosed between the ages of 65–69, 29% between the ages of 70–74, 23% between the ages of 75–79, and 19% were 80 or older. Tables 1.a and 1.b show the distribution of other patient characteristics categorized by race and by age.

Table 1.

| a Study Sample Characteristics by Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | White non-Hispanic | African-American | White Hispanic | |||||

| N | % | N | Col % | N | Col % | N | Col % | |

| Period (p < 0.01) | ||||||||

| 1998 | 13,447 | 11.78% | 10,835 | 11.57% | 1,641 | 13.09% | 971 | 12.12% |

| 1999 | 14,191 | 12.43% | 11,534 | 12.32% | 1,614 | 12.87% | 1,043 | 13.02% |

| 2000 | 28,614 | 25.06% | 23,571 | 25.18% | 3,100 | 24.73% | 1,943 | 24.26% |

| 2001 | 29,039 | 25.44% | 23,954 | 25.59% | 3,083 | 24.59% | 2,002 | 25.00% |

| 2002 | 28,871 | 25.29% | 23,722 | 25.34% | 3,099 | 24.72% | 2,050 | 25.60% |

| Age (p < 0.01) | ||||||||

| 65 – 69 years old | 33,683 | 29.50% | 26,561 | 28.37% | 4,402 | 35.11% | 2,720 | 33.96% |

| 70 – 74 years old | 33,382 | 29.24% | 27,351 | 29.22% | 3,596 | 28.68% | 2,435 | 30.40% |

| 75 – 79 years old | 25,947 | 22.73% | 21,633 | 23.11% | 2,593 | 20.68% | 1,721 | 21.49% |

| 80 + years old | 21,150 | 18.53% | 18,071 | 19.30% | 1,946 | 15.52% | 1,133 | 14.15% |

| Married (p < 0.01) | ||||||||

| Yes | 78,562 | 68.82% | 66,118 | 70.63% | 6,842 | 54.57% | 5,602 | 69.95% |

| No | 35,600 | 31.18% | 27,498 | 29.37% | 5,695 | 45.43% | 2,407 | 30.05% |

| Living Area (p < 0.01) | ||||||||

| Big Metro | 72,580 | 63.58% | 56,798 | 60.67% | 10,088 | 80.47% | 5,694 | 71.10% |

| Metro | 27,775 | 24.33% | 24,155 | 25.80% | 1,742 | 13.89% | 1,878 | 23.45% |

| Urban | 5,118 | 4.48% | 4,745 | 5.07% | 232 | 1.85% | 141 | 1.76% |

| Less Urban | 7,140 | 6.25% | 6,431 | 6.87% | 431 | 3.44% | 278 | 3.47% |

| Rural | 1,549 | 1.36% | 1,487 | 1.59% | 44 | 0.35% | 18 | 0.22% |

| State Buy-In (p < 0.01) | ||||||||

| Yes | 6,640 | 5.82% | 3,074 | 3.28% | 1,656 | 13.21% | 1,910 | 23.85% |

| No | 107,522 | 94.18% | 90,542 | 96.72% | 10,881 | 86.79% | 6,099 | 76.15% |

| PSA (p < 0.01) | ||||||||

| Available | 87,923 | 77.02% | 72,295 | 77.23% | 9,548 | 76.16% | 6,080 | 75.91% |

| Not Available | 26,239 | 22.98% | 21,321 | 22.77% | 2,989 | 23.84% | 1,929 | 24.09% |

| b Study Sample Characteristics by Age Category | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 65 – 69 years old | 70 – 74 years old | 75 – 79 years old | 80+ years old | |||||||

| N | % | N | Col % | N | Col % | N | Col % | N | Col % | ||

| Period (p < 0.05) | |||||||||||

| 1998 | 13,447 | 11.78% | 3,955 | 11.74% | 3,897 | 11.67% | 3,101 | 11.95% | 2,494 | 11.79% | |

| 1999 | 14,191 | 12.43% | 4,140 | 12.29% | 4,212 | 12.62% | 3,271 | 12.61% | 2,568 | 12.14% | |

| 2000 | 28,614 | 25.06% | 8,271 | 24.56% | 8,497 | 25.45% | 6,542 | 25.21% | 5,304 | 25.08% | |

| 2001 | 29,039 | 25.44% | 8,637 | 25.64% | 8,511 | 25.50% | 6,571 | 25.32% | 5,320 | 25.15% | |

| 2002 | 28,871 | 25.29% | 8,680 | 25.77% | 8,265 | 24.76% | 6,462 | 24.90% | 5,464 | 25.83% | |

| Married (p < 0.01) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 78,562 | 68.82% | 24,920 | 73.98% | 24,096 | 72.18% | 17,555 | 67.66% | 11,991 | 56.70% | |

| No | 35,600 | 31.18% | 8,763 | 26.02% | 9,286 | 27.82% | 8,392 | 32.34% | 9,159 | 43.30% | |

| Living Area (p < 0.01) | |||||||||||

| Big Metro | 72,580 | 63.58% | 21,684 | 64.38% | 21,297 | 63.80% | 16,553 | 63.80% | 13,046 | 61.68% | |

| Metro | 27,775 | 24.33% | 8,201 | 24.35% | 8,175 | 24.49% | 6,249 | 24.08% | 5,150 | 24.35% | |

| Urban | 5,118 | 4.48% | 1,434 | 4.26% | 1,468 | 4.40% | 1,163 | 4.48% | 1,053 | 4.98% | |

| Less Urban | 7,140 | 6.25% | 1,954 | 5.80% | 1,999 | 5.99% | 1,641 | 6.32% | 1,546 | 7.31% | |

| Rural | 1,549 | 1.36% | 410 | 1.22% | 443 | 1.33% | 341 | 1.31% | 355 | 1.68% | |

| State Buy-In (p < 0.01) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 6,640 | 5.82% | 1,662 | 4.93% | 1,957 | 5.86% | 1,494 | 5.76% | 1,527 | 7.22% | |

| No | 107,522 | 94.18% | 32,021 | 95.07% | 31,425 | 94.14% | 24,453 | 94.24% | 19,623 | 92.78% | |

| PSA (p < 0.01) | |||||||||||

| Available | 87,923 | 77.02% | 27,770 | 82.45% | 26,969 | 80.79% | 19,759 | 76.15% | 13,425 | 63.48% | |

| Not Available | 26,239 | 22.98% | 5,913 | 17.55% | 6,413 | 19.21% | 6,188 | 23.85% | 7,725 | 36.52% | |

AA patients were diagnosed with PC at relatively younger ages (chi-square test: p < 0.01); 35% of AA were diagnosed at ages 65–69 compared to only 28% of Whites, while only 16% of AA were diagnosed at age 80+ compared to 19% of Whites.

Table 1.b shows that the percentage of men who were married at diagnosis decreased with age from 74.0% to 56.7% (chi-square test: p < 0.01), while Table 1.a shows that the proportion of married White men was 29% greater than married AA men (chi-square test: p < 0.01).

White Hispanic patients diagnosed with PC were 7.3 times more likely, and AA patients were 4.0 times more likely to receive some financial assistance related to healthcare coverage from the state compared to White non-Hispanics (chi-square test: p < 0.01).

The proportion of patients who received a PSA test prior to their PC diagnosis ranged from 76.2% to 77.2% (chi-square test: p < 0.01) across racial/ethnic groups. There was a much wider range across age groups; the proportion of men with a prior PSA test decreased from 82.5% for patients aged 65–69 to 63.5% for patients aged 80+ (chi-square test: p < 0.01).

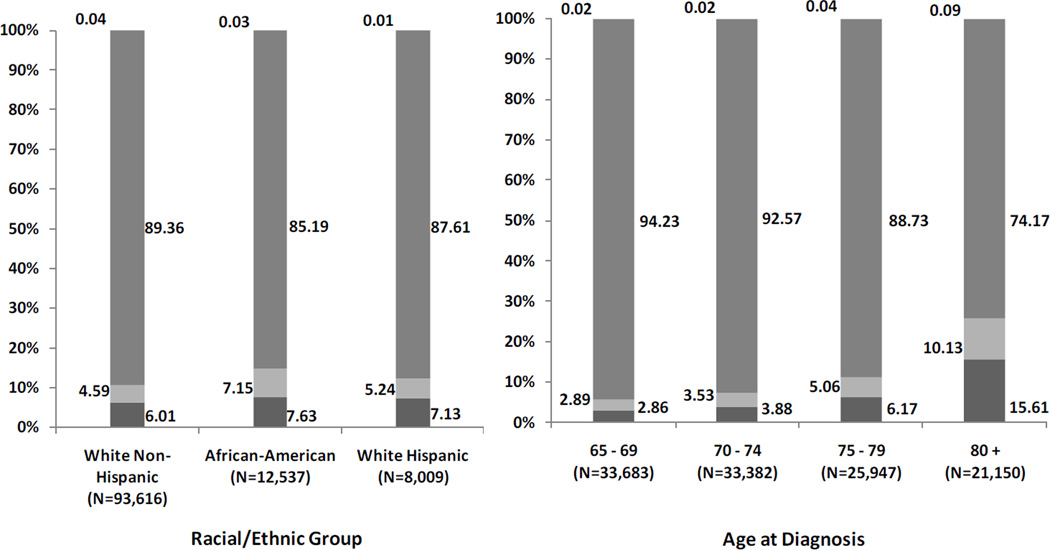

Figures 1.a and 1.b represent the distribution of historical stage by race (chi-square test: p < 0.01) and age (chi-square test: p < 0.01), respectively. Figure 1.a shows that 6% to 8% of all men with PC were not staged. In addition, AA were 56% more likely to be staged with distant metastasis and 27% more likely to be unstaged compared to non-HW. Figure 1.b shows that the proportion of unstaged patients by age group ranged from 3% (age 65–69) to 16% (age 80+). In addition, patients 80 and older were 3.51 times more likely to be staged with distant metastatic disease and 5.46 times more likely to be unstaged compared to the reference group (65–69 year olds).

Figure 1.

a Staging Distribution of Elderly SEER-Medicare Prostate Cancer Patients by Race/Ethnicity

Unstaged (N=7,158)

Unstaged (N=7,158)

Distant (N=5,609)

Distant (N=5,609)

Local/Regional (N=101,351)

Local/Regional (N=101,351)

In-situ (N=44)

In-situ (N=44)

b Staging Distribution of Elderly SEER-Medicare Prostate Cancer Patients by Age

Unstaged (N=7,158)

Unstaged (N=7,158)

Distant (N=5,609)

Distant (N=5,609)

Local/Regional (N=101,351)

Local/Regional (N=101,351)

In-situ (N=44)

In-situ (N=44)

Tables 2.a and 3.a present results from the two regression models without interactions. The outcome of the first model is being staged and that of the second model is being staged with distant metastatic versus in-situ or local/regional disease conditional on being staged. According to these models, the observed disparities in PC staging remain even after controlling for covariates.

Table 2.

| a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors Influencing The Odds Of Seer-Medicare Prostate Cancer Patients Being Staged1 | |||

| Adjusted Odds Ratios | |||

| Point Estimate |

95% Wald Confidence Limits |

||

| Race | |||

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African-American** | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.86 |

| White Hispanic | 0.99 | 0.89 | 1.11 |

| Age | |||

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old** | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.82 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.56 |

| 80+ years old** | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.24 |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||

| 1998 (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1999 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.02 |

| 2000** | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.29 |

| 2001** | 1.71 | 1.55 | 1.88 |

| 2002** | 1.64 | 1.49 | 1.81 |

| b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors Influencing The Odds Of Seer-Medicare Prostate Cancer Patients Being Staged1 / With Time Trend Interactions / | ||||

| Adjusted Odds Ratios | ||||

| Point Estimate |

95% Wald Confidence Limits |

|||

| Race |

Year of Diagnosis |

|||

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 1998 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 1998 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 1.23 |

| African-American | 1998 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 1.02 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 1999 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 1999 | 1.18 | 0.91 | 1.52 |

| African-American ** | 1999 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.86 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 2000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 2000 | 0.97 | 0.80 | 1.17 |

| African-American ** | 2000 | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.94 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 2001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 2001 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 1.17 |

| African-American ** | 2001 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.88 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 2002 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 2002 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 1.21 |

| African-American | 2002 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 1.03 |

| Age | ||||

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 1998 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old | 1998 | 0.80 | 0.63 | 1.02 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 1998 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.60 |

| 80+ years old** | 1998 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.27 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 1999 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old** | 1999 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.83 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 1999 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.52 |

| 80+ years old** | 1999 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.25 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 2000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old** | 2000 | 0.69 | 0.59 | 0.81 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 2000 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.67 |

| 80+ years old** | 2000 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.27 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 2001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old | 2001 | 0.88 | 0.72 | 1.06 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 2001 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.68 |

| 80+ years old** | 2001 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 2002 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old* | 2002 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.96 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 2002 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.61 |

| 80+ years old** | 2002 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.25 |

Significant at p < 0.05

Significant at p < 0.01

The model controls for marital status, urban/rural living area, state buy-in (low income), PSA test prior to diagnosis, census tract median household income by race, and SEER cancer registry.

Table 3.

| a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors Influencing The Odds Of Seer-Medicare Prostate Cancer Patients Being Staged With Distant Disease1 | |||

| Adjusted Odds Ratios | |||

| Point Estimate |

95% Wald Confidence Limits |

||

| Race | |||

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African-American** | 1.61 | 1.47 | 1.76 |

| White Hispanic | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.19 |

| Age | |||

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old** | 1.25 | 1.15 | 1.36 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 1.85 | 1.70 | 2.02 |

| 80+ years old** | 4.33 | 3.99 | 4.69 |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||

| 1998 (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1999** | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.94 |

| 2000** | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| 2001** | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.87 |

| 2002** | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.83 |

| b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors Influencing The Odds Of Seer-Medicare Prostate Cancer Patients Being Staged With Distant Disease1 / With Time Trend Interactions / | ||||

| Adjusted Odds Ratios | ||||

| Point Estimate |

95% Wald Confidence Limits |

|||

| Race |

Year of Diagnosis |

|||

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 1998 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 1998 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.35 |

| African-American** | 1998 | 1.55 | 1.26 | 1.90 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 1999 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 1999 | 1.16 | 0.88 | 1.55 |

| African-American ** | 1999 | 1.52 | 1.21 | 1.90 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 2000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 2000 | 0.82 | 0.65 | 1.04 |

| African-American ** | 2000 | 1.70 | 1.46 | 1.99 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 2001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic ** | 2001 | 1.42 | 1.17 | 1.72 |

| African-American ** | 2001 | 1.46 | 1.24 | 1.73 |

| White Non-Hispanic (Ref.) | 2002 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White Hispanic | 2002 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 1.18 |

| African-American ** | 2002 | 1.75 | 1.49 | 2.05 |

| Age | ||||

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 1998 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old** | 1998 | 1.39 | 1.11 | 1.74 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 1998 | 1.86 | 1.48 | 2.33 |

| 80+ years old** | 1998 | 4.27 | 3.44 | 5.29 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 1999 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old | 1999 | 1.10 | 0.87 | 1.38 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 1999 | 1.56 | 1.24 | 1.96 |

| 80+ years old** | 1999 | 3.48 | 2.80 | 4.32 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 2000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old* | 2000 | 1.22 | 1.03 | 1.45 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 2000 | 1.83 | 1.54 | 2.16 |

| 80+ years old** | 2000 | 4.17 | 3.56 | 4.88 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 2001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old** | 2001 | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.58 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 2001 | 1.78 | 1.49 | 2.12 |

| 80+ years old** | 2001 | 4.57 | 3.90 | 5.36 |

| 65 – 69 years old (Ref.) | 2002 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70 – 74 years old | 2002 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 1.45 |

| 75 – 79 years old** | 2002 | 2.15 | 1.80 | 2.56 |

| 80+ years old** | 2002 | 4.81 | 4.08 | 5.66 |

Significant at p < 0.05

Significant at p < 0.01

The model controls for marital status, urban/rural living area, state buy-in (low income), PSA test prior to diagnosis, census tract median household income by race, and SEER cancer registry.

The adjusted odds ratio estimates in Table 2.a indicate that 70–74, 75–79, and 80+ year old men are 0.76, (95% CI = 0.69 – 0.82), 0.52 (95% CI = 0.48 – 0.56), and 0.23 (95% CI = 0.21 – 0.24) times as likely to be staged relative to PC patients aged 65–69. The odds of being staged for AA are 0.78 times that of non-HW (95% CI = 0.72 – 0.86). The likelihood of being staged in 1999, compared to 1998, did not significantly differ (95% CI = 0.84 – 1.02). However, the model shows that the odds of being staged improved in 2000, 2001, and 2002 versus 1998. The corresponding odds ratio estimates are 1.18 (95% CI = 1.07 – 1.29), 1.71 (95% CI = 1.55 – 1.88), and 1.64 (95% CI = 1.49 – 1.81).

The adjusted odds ratio estimates in Table 3.a provide additional insight into PC staging. They show that the probability of distant metastatic PC versus in situ or local/regional disease is higher for AA (OR = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.47 – 1.76) and older men (OR = 1.25 [95% CI = 1.15 – 1.36], 1.85 [95% CI = 1.70 – 2.02], and 4.33 [95% CI = 3.99 – 4.69] for 70–74, 75–79, and 80+ versus 65–69 year olds)

Table 3.a contains estimates from the sub-stage model for being staged with distant metastatic disease among the staged patients. It demonstrates that the odds of being staged with distant disease steadily decreased from 1998 to 2002. The odds ratio estimates are 0.85 (95% CI = 0.76 – 0.94), 0.83 (95% CI = 0.76 – 0.92), 0.79 (95% CI = 0.72 – 0.87), and 0.76 (95% CI = 0.69 – 0.83) for men diagnosed with PC in 1999, 2000, 2001 and 2002 versus 1998.

Tables 2.b and Table 3.b contain results from two alternative models that control for the same covariates as before, but also include interaction terms of race and age with year of diagnosis. Table 2.b shows that the positive increase observed in Table 2.a in the likelihood of PC staging over time did not narrow the observed racial and age disparities in cancer staging. The odds of being staged for AA patients remained between 0.71 (95% CI = 0.58 – 0.86) and 0.85 (95% CI = 0.71 – 1.03) times that of non-HW diagnosed in the same year. Similarly, differences in PC staging between older and younger patients remained relatively unchanged throughout the study period (Table 2.b). For instance, the odds ratios of 70–74 relative to 65–69 year old patients remained between 0.65 (95% CI = 0.52 – 0.83) and 0.88 (95% CI = 0.72 – 1.06) for all years of diagnosis,

Table 3.b tells a similar story. Even though the likelihood of being staged with distant metastatic disease decreased over the 1998–2002 period, as seen in Table 3.a, the racial gap in staging remained consistent and the odds ratios of being staged with distant disease for AA versus Whites remained between 1.46 (95% CI = 1.24 – 1.73) and 1.75 (95% CI = 1.49 – 2.05) for each year. The age gap also remained despite the overall decrease in the likelihood of being staged with distant metastatic disease. For example, the odds ratios of 80+ relative to 65–69 year old patients stayed between 3.48 (95% CI = 2.80 – 4.32) and 4.81 (95% CI = 4.08 – 5.66) for all years of diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

In general, over time there has been an increase in the proportion of PC patients who are being staged. However, our analysis of SEER-Medicare data showed that elderly and AA PC patients were less likely to be staged than other men with PC. This result was consistent across the time intervals examined, and there was no evidence of improvement in these age and racial disparities gaps. Some may argue that watchful waiting is an option and may be preferred by a proportion of elderly or AA men. Nonetheless, it seems contrary to informed decision-making to select a management option, including watchful waiting, in the absence of staging information.

Our results that the racial disparities gap did not decrease are consistent with a recent study by Gross and colleagues who examined SEER-Medicare data for the 1992 to 2002 time period.13 Their findings suggest that racial disparities in treatment for PC with “definitive therapy,” defined as prostatectomy, brachytherapy, or external beam radiation, did not change over time. 13

A separate study by Abraham and colleagues reported a reduction in racial disparities in the staging evaluation for PC. Their results showed that AA men were less likely to undergo bone scan than White men during 1991 to 1994, but this disparity was no longer seen between 1995 and 1999.14

Our analysis explored changes in staging over time and, therefore, we chose to use the historical stage variable as the parameter to assess PC status in patients. As previously noted, SEER uses the EOD classification system as its primary staging system. EOD was designed for use by tumor registrars rather than physicians, and is applied to data derived from the medical record rather than direct examination of the patient. In the present analysis, we used the SEER historic stage variable, which is a collapsed version of EOD, and is maintained by the NCI in accordance with the End Results Group recommendations for using the historical staging variable to examine changes in staging over time. Ultimately, our decision to accept the historical staging variable instead of the AJCC staging variable was based on empirical model specification using the regression error specification test (RESET) developed by Sunil Sapra.17

This study has some limitations that are related to the use of SEER-Medicare data. First, the generalizability of our findings may be limited only to the elderly (65+) population covered by Medicare. Furthermore, despite the wide geographic spread of SEER registries, these registries intentionally oversample minorities and therefore may not be nationally representative. Second, potentially important explanatory variables, such as measures of social support, and patient beliefs and preferences, which will influence the decision to obtain staging information, are absent from the data. Third, the socioeconomic patient characteristics available in SEER are measured at the census tract level, and as ecologic variables, are subject to variability within the census tract. In addition, we did not control for comorbidity in our analysis. While comorbidities may influence treatment decisions, they are less likely to influence the decision as to whether or not staging information should be obtained for a patient diagnosed with PC.

The observed racial and age disparities in PC staging and treatment are still not fully explained. The contributing causes include some combination of biology, patient preferences, quality of care and access barriers, comorbidity and perhaps some unintended disparities in treatment.

CONCLUSION

In addition to prior reports that African American and older men are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced staged prostate cancer, we find that there also is a higher probability that African American and older men with prostate cancer will not be staged. These results are based upon historical SEER-Medicare data and document that there are disparities among diagnosed prostate cancer patients in the probability of being staged. Furthermore, prostate cancer staging did not improve from the years 1998 to 2002 for African-American men and older men.. In addition, when staging did take place, the probability of having distant metastatic disease was higher for African-American men and also for all men as they aged, compared to the reference group of 65–69 year olds. Part of the observed disparities in staging may reflect informed patient decision-making, but continued monitoring and education regarding new treatment options should continue for all men with prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements and Disclosures:

This work was supported by sanofi-aventis US. Part of Dr. Hussain’s salary is supported by a Merit Review Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Part of Dr. Mullins? salary for health disparities research is supported by grant NCMHD/NIH #P60 MD000532 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the VA, or sanofi-aventis US. The authors wish to acknowledge Van Doren Hsu, PharmD, and the Pharmaceutical Research Center (PRC) for data management and analytic support and Vu Cap for technical assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Brian Seal is an employee of Sanofi-Aventis. C. Daniel Mullins and Arif Hussain received consulting and/or grant support from Sanofi-Aventis and Pfizer, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

C. Daniel Mullins, Pharmaceutical Health Services Research Department, University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy.

Eberechukwu Onukwugha, Pharmaceutical Health Services Research Department, University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy.

Kaloyan Bikov, Pharmaceutical Health Services Research Department, University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy.

Brian Seal, Sanofi-Aventis, Inc..

Arif Hussain, Greenebaum Cancer Center, University of Maryland, School of Medicine and Baltimore VA Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen JH, Schoenbach VJ, Kaufman JS, et al. Racial differences in clinical progression among Medicare recipients after treatment for localized prostate cancer (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:803. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilligan T, Wang PS, Levin R, et al. Racial Differences in Screening for Prostate Cancer in the Elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1858. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States: findings from the National Program of Cancer Registries Patterns of Care Study. Cancer. 2008;113:582. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell IJ. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Prostate Cancer in African-American Men. The Journal of Urology. 2007;177:444. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godley PA, Schenck AP, Amamoo MA, et al. Racial Differences in Mortality among Medicare Recipients after Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1702. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tewari A, Horninger W, Pelzer AE, et al. Factors contributing to the racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. BJU Int. 2005;96:1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Harlan LC, et al. Trends and black/white differences in treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Med Care. 1998;36:1337. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shavers VL, Brown M, Klabunde CN, et al. Race/ethnicity and the intensity of medical monitoring under 'watchful waiting' for prostate cancer. Med Care. 2004;42:239. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000117361.61444.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prostate Cancer Institute. Watchful Waiting. 2009 vol. [Google Scholar]

- 10.AJCC: The American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for Staging. 5th. Lippin-Cott Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SEER Fast Fact Sheet. Prostate. 2009 vol. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross CP, Smith BD, Wolf E, Martin A. Racial disparities in cancer therapy. Cancer. 2008;112:900. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham N, Wan F, Montagnet C, et al. Decrease in racial disparities in the staging evaluation for prostate cancer after publication of staging guidelines. The Journal of Urology. 2007;178:82. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosmer DW, Lemesbow S. Goodness of fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods. 1980;9:1043. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapra S. A regression error specification test (RESET) for generalized linear models. Economics Bulletin. 2005;3:1. [Google Scholar]