Abstract

The epigenetic control of neuronal gene expression patterns has emerged as an underlying regulatory mechanism for neuronal function, identity and plasticity, where short-to long-lasting adaptation is required to dynamically respond and process external stimuli. To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the physiology and pathology of the brain, it becomes essential to understand the mechanisms that regulate the epigenome and transcriptome in neurons. Here, we review recent advances in the study of regulated neuronal gene expression, which are dramatically expanding as a result of the development of new and powerful contemporary methodologies, based on the power of next-generation sequencing. This flood of new information has already transformed our understanding of the biology of cells, and is now driving discoveries elucidating the molecular mechanisms of brain function in cognition, behavior and disease, and may also inform the study of neuronal identity, diversity and cell reprogramming.

Introduction

Epigenetics is a fascinating and rapidly growing field of biology that investigates stable, heritable, but yet dynamic and reversible changes in chromatin modifications that have a direct impact on regulation of transcription. Epigenetic mechanisms assure precise transcriptional response to intrinsic and extrinsic signals, and enable the storage of regulatory information in the genome even after signals have subsided. Epigenetic modifications have already been proven to be a core mechanism of many neuronal processes, from the establishment of neuronal identity to individual adaptation throughout life, including a vast diversity of mental disorders.

The epigenome (the pattern of epigenetic modifications in the genome) is the result of a complex interplay between enzymes that modify DNA and histones, proteins that can recognize these modifications, sequence-specific and non-specific DNA binding factors, scaffold proteins, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), the chromatin structure and the organization of the genome in the nuclear space. The epigenome plays an essential role in the regulatory mechanisms that define the transcriptome (the profile of all the transcripts expressed in a cell). Hence, the analysis of the epigenome and transcriptome can be indicative of what defines a cell type, its physiological state, and pathological stage in a disease.

There are two main categories of epigenetic modifications or “marks”: DNA methylation and histone post-translational modifications. The precise spatial and temporal deposition and removal of these marks is crucial to dictate the epigenomic state of a cell, and it is achieved by the combinatorial action of different classes of histone- and DNA-modifying enzymes. These proteins can be classified as “readers”, “writers” or “erasers” based on their ability to recognize, add or remove epigenetic modifications, respectively. Distinct epigenetic marks, in turn, can recruit multiprotein complexes harboring different enzymatic activities and thus amplifying the combinatorial potential of epigenetic marks. Finally, transcription factors orchestrate the expression of distinct sets of genes by recognizing sequence-specific motifs in the genome and recruiting the necessary machinery to initiate and maintain the transcriptional response.

In the past few years, striking advances in genomic technologies based on deep sequencing have revolutionized our understanding of epigenetic regulation of transcription, shifting our focus from the classical single-locus experimental approach to studying epigenetic events on a genome-wide scale. Deep sequencing outputs provide relatively short DNA reads [50-400bp] (Kircher and Kelso, 2010), which renders it especially amenable for assays dedicated to the study of regulation of gene expression. It is beyond the scope of this Review to describe all possible applications. A schematic overview of these approaches is shown in Figure 1 and a brief description of them can be found in Table 1. In this Review, we attempt to highlight the way in which recent advances in technologies that survey the genome, epigenome and transcriptome are expanding our understanding of the role of epigenetic processes in gene regulation in neuronal as well as in non-neuronal systems, and we will discuss the relevance of these findings for elucidating brain function and disease.

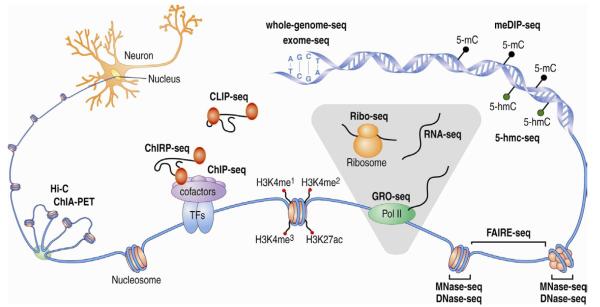

Figure 1. A high diversity of next-generation or deep sequencing approaches is currently available for profiling genomes, epigenomes, methylomes, and transcriptomes.

A plethora of deep sequencing approaches are now available, ranging from approaches to map the primary sequence of DNA (whole-genome-seq and exome-seq), mapping DNA methylation marks (meDIP-seq, 5-hmC-seq, and many others), profiling chromatin structure (MNase-seq, DNaseI-seq, and FAIRE-seq), profiling all the different stages of the transcriptome (GRO-seq, RNA-seq, and ribo-seq), profiling transcription factors, cofactors, and histone marks (ChIP-seq), profiling RNA interactions to the genome or the transcriptome (ChIRP-seq and CLIP-seq, and variants), to finally profile the structure of the genome in the tridimensional space (ChIA-PET, HiC, and several others). All these approaches are now available for the neurobiology community and are primed to revolutionize the field.

|

Assays profiling the association of

methylated marks to the genome |

Affinity enrichment-based

assays |

MeDIP-seq (Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation), MBD- seq |

Based on immunoisolation of methylated DNA fragments using an antibody that recognizes 5-methylcytosine (MeDIP-seq) or using the methyl-binding-domains of MBD2 or MeCP2 (MBD-seq). |

|

Enzyme digestion-based

assays |

MRE-seq (Methylation-sensitive Restriction Enzyme) | Based on cleavage of DNA by methylation sensitive restriction enzymes to fragment DNA at methylation sites before sequencing. |

|

|

Bisulfite conversion-based

assays |

Bis-seq (Bisulfite-sequencing), Reduced Representation Bis- Seq (RRBS). |

Based on the chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine into uracil. Identifies methylated cytosines at nucleotide resolution by comparison to untreated DNA samples or reference genome. Bisulfate based approaches can be combined with pre-enrichment methods, such as array capture or bead technology, which can enrich specific DNA genomic regions for sequencing. |

|

|

OxBS-seq (Oxidative bisulfite), TAB-seq (Tet-assisted bisulfite), and 5-hmCyt-seq (5hydroxy-methylcytosine) |

Variants of Bis-seq that specifically discriminate between 5-mC and 5-hmC | ||

|

Assays profiling the association of proteins/histone marks/RNA to the

genome |

ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation) | Based on enrichment of crosslinked DNA-protein complex isolated by an antibody raised against a protein or specific histone mark of interest. The bound chromatin fraction is identified by deep sequencing. |

|

| ChiRP-Seq (Chromatin RNA Immunoprecipitation) | Variant of ChIP-seq that specifically detects association of RNA molecules to the genome. Based on hybridization of a pool of non-overlapping, biotinylated oligonucleotides that complement to the sequence of the RNA of interest. The bound DNA are processed as in ChIP-seq |

||

| Assays profiling the association of proteins to (RNA) the transcriptome |

CLIP-seq (Crosslinking and Immunoprecipitation ) PAR-CLIP (Photoactivatable Ribonucleoside-enhanced- CLIP) |

Based on UV-crosslinking to stabilize RNA and RNA-binding proteins interactions, followed by immunoisolation of the RNA-protein complex using a specific antibody for the protein. Enriched RNAs are then converted into cDNAs for sequencing (CLIP-seq). PAR-CLIP differs from CLIP-seq in the incorporation of photoactivatable ribonucleoside analogs into the nascent transcripts that facilitate UV-crosslinking between labeled RNAs and proteins. |

|

| Assays profiling nucleosome positioning |

MNase-seq (Micrococcal Nuclease), DNase-seq (DNase I hypersensitive sites sequencing), FAIRE-seq (Formaldehyde Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) |

Nucleosome positioning is identified by sequencing DNA that is protected by nucleosomes from digestion by micrococcal nucleases (MNase-seq). Alternatively, open chromatin regions are identified and sequenced based on their hypersensitivity to DNase I digestion (DNase-seq) or based on their solubility in the aqueous phase during phenol-chloroform extraction after formaldehyde crosslinking (FAIRE-seq). |

|

| Assays profiling the organization of the genome in the nuclear space | 3C, 4C, Hi-C, ChIA-PET | Chromosome conformation capture techniques determine the physical interaction between known genome regions (3C), unknown regions of the genome and a known bait (4C) or all genome-wide occurring interaction in an unbiased fashion (Hi-C). ChiA-PET involves an immunoisolation step that allows the identification of the genomic interaction sites of a specific protein. |

|

| Assays profiling the transcriptome | RNA-seq, miR-seq |

RNA-seq profiles transcripts genome-wide in their steady-state form. Different information can be obtained based on the specific pool of RNAs utilized, such as nuclear, cytoplasmic, or based on specific strategies of enrichment, such as polyadenylated RNAs or small RNAs (i.e. miR-seq). |

|

| Ribo-seq (ribosome profiling) | Ribo-seq profiles transcripts undergoing translation, based on sequencing ribosome-associated RNAs. Tagging strategies of ribosomal proteins allow their affinity purification. |

||

| GRO-seq (Global Run-on) |

GRO-seq profiles nascent transcripts exclusively undergoing transcription. It is based on the rapid isolation of nuclei and subsequent addition of biotinylated nucleotides during a short period in which transcription is allowed to shortly proceed in vitro, effectively mapping the position, amount, and orientation of transcriptionally engaged RNA polymerases genome-wide. |

||

Re-defining the organization of the genome and control of transcription in neural function

The combination of deep sequencing with molecular biology techniques provides for the first time the means to study not just expression, but also regulation of transcription at the whole-genomic level. In particular, the profiling of histone marks by chromatin immunoprecipitation combined with deep sequencing (ChIP-seq – see Table 1) has been instrumental in the functional re-definition of the genome, including a more comprehensive annotation of gene bodies, promoters, insulators and enhancers regions (Barski et al., 2007; Heintzman et al., 2009; Heintzman et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2008). Most recently, a slew of publications from The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Project (www.nature.com/encode) provides a broad and detailed analysis of structures and functions of genomic elements (Bernstein et al., 2012). For example, it has been calculated that 56% of the genome consists of regions highly enriched in epigenetically modified histones, although this number may easily increase with the discovery and mapping of new histone marks (Tan et al., 2011). This finding implies that a large proportion of what was once called “junk DNA” might indeed be critical for proper regulation of gene expression.

Another seminal finding coming from the application of deep sequencing is the observation that the human genome is pervasively transcribed. Based on RNA-seq analysis, the ENCODE Project currently estimates that as much as 76% of the genome is transcribed, of which only ~35% lies within protein-coding genes. Therefore, over half of the RNA molecules that have been detected correspond to ncRNAs, including at least 8,800 small (<200 nucleotide) and 9,600 long (>200 nucleotide) RNAs (Djebali et al., 2012). These ncRNAs encompass classes of RNA previously described (e.g., tRNAs, snoRNAs and miRNAs) but also new ones of mostly yet unknown function and structure (discussed in a later section). In this respect, the application of assays to profile RNAs that are specifically undergoing transcription, such as the global run-on experiment (GRO-seq), will be a valuable tool to complement the catalog of transcribed regions (Core et al., 2008).

Promoters

Gene promoters can now be predicted based on the presence of the promoter-specific histone mark, H3K4me3. Additional histone marks can be used to identify promoters in a particular transcriptional state. For example, association of H3K4me3 with H3K9ac and H3K27ac usually correlates with promoters of actively transcribed genes, whereas H3K4me3 associated with H3K27me3 correlates with promoters of genes that are primed for activation but not transcribed (“poised genes”). In neuronal progenitors, H3K4/27me3-marked promoters (so called “bivalent domains”) are associated with genes of differentiated neurons and glia (Bernstein et al., 2006) (Garrison et al., 2007). Interestingly, independent of cell type, many promoters harbor H3K4me3, suggesting their competence for activation even when RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is not actively transcribing their corresponding genes, thus essentially defining most genes as “poised” for elongation (Heintzman et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2012). This type of polymerase “stalling” may operate in all cell types, including neurons, although the precise mechanisms required for establishing poised promoters have not yet been defined.

Enhancers

An innovative accomplishment of deep sequencing technologies has been the mapping and characterization of enhancers at genome-wide scale. Enhancers are cis-acting regulatory elements that can enhance gene transcription from a distance and independently of orientation. As a result of numerous genome-wide studies, enhancers have emerged as regulatory elements that drive cell-type-specific patterns of gene expression through binding of cell/lineage-specific transcription factors. Enhancers contain distinctive histone modification patterns and histone variants compared with other cis-regulatory elements in the genome. For example, Ren and colleagues made a seminal contribution observing that enhancers show H3K4me1 in the absence/low levels of H3K4me3, and are enriched in the histone variant H2A.Z (Heintzman et al., 2007). In addition, enhancers that harbor H3K27ac strongly correlate with cell-type-specific gene expression programs (Heintzman et al., 2009). Similarly, enrichment of specific cofactors has been reported to be part of a general enhancer signature. For example, the histone acetyltransferase p300 has been found to be an effective predictor of functional enhancers in a tissue-specific manner (Visel et al., 2009). Similarly, Greenberg and colleagues have reported that the p300-related acetyltransferase, CBP, along with RNAPII, is recruited in an activity-dependent manner at enhancer regions upon neuronal response to KCl treatment (Kim et al., 2010). The authors have further shown that enhancer elements are actively transcribed, uncovering a novel type of long non-coding RNAs (eRNAs). Although the functional relevance of these transcripts is still an open question, their expression levels are intimately correlated with mRNA expression at nearby genes, and hence they might be useful to determine functional enhancers (Kim et al., 2010; Sanyal et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011). Another common feature of enhancers is their occupancy by specific combinations of cell/lineage-specific transcription factors. For example, a comprehensive classification of enhancers in seventeen mouse tissues, including adult cerebellum, cortex and embryonic E14.5 brains, revealed the existence of neuronal subtype-specific enhancers (cortex–, cerebellum–, or E14.5 brain specific) that contain consensus DNA binding sites for a common set of neuronal transcription factors (e.g., Atoh1 motif in cerebellum-specific enhancers) (Shen et al., 2012). Finally, promoters and enhancers engage in long-range interactions, raising the question of whether this physical association functions as an additional step to control the proper transcriptional outcome (Sanyal et al., 2012). The mechanisms by which enhancers contribute to regulation of transcription is still under intense investigation; however, one hypothesis is that these elements regulate both polymerase recruitment and polymerase release from poised promoters and thus the rate of transcription occurs in a cell type/lineage- and/or signal-specific manner (Hah et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011).

Transcription factors

Studies in almost every system have shown that tissue-specific gene expression is tightly regulated by the coordination of lineage-specific transcription factors. The application of ChIP-seq and previously ChIP-chip technologies has been instrumental in uncovering the regulatory mechanism by which these proteins act at a genome-wide scale. For example, it has been observed that only a relatively small number of binding events of cell-type specific transcription factors occurs at promoter regions, while the vast majority of these events occurs at distal regulatory elements including enhancers. Deep-sequencing technologies developed to profile the chromatin structure (e.g., DNase-seq, MNase-seq, and FRAIRE-seq; Table I) have also confirmed at genome-wide scale that these events occur at “open” chromatin regions (Thurman et al., 2012).

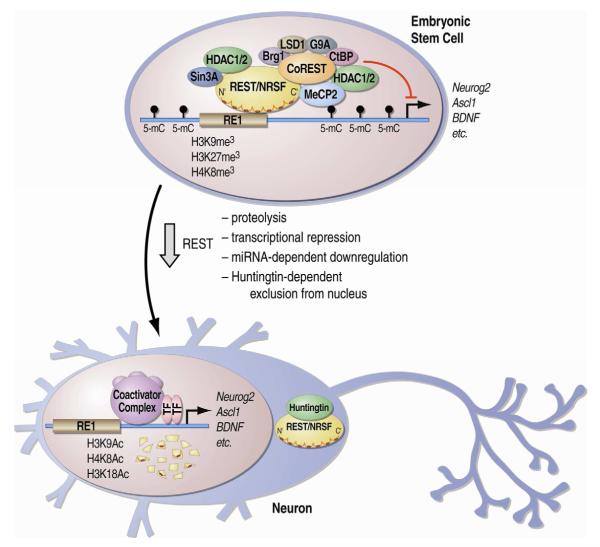

One of the classic transcription factors that govern neuronal identity is the neuron-restrictive silencer factor, NRSF/REST. A large body of evidence shows how REST represses transcription in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or non-neuronal cells through epigenetic processes upon binding to thousands of sites in the genome, as detected by ChIP-seq (Johnson et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2009). As illustrated in Figure 2, REST/NRSF-mediated repression in ESCs is achieved through recruitment of two separate co-repressor complexes, mSin3 and CoREST, that in turn act as molecular scaffolds for DNA/histone-modifying enzymes and chromatin-remodeling factors, including histone deacetylases (e.g., HDAC1/2), demethylases (e.g., LSD1), and methyltransferases (e.g., G9a). These enzymes dictate a repressive chromatin state for a specific subset of genes, exhibiting an enhancement in methylated histone marks implicated in transcriptional silencing (Coulson, 2005; Qureshi and Mehler, 2009). During neuronal differentiation or in neuronal cells, REST protein level is decreased and loss of its binding from many genomic sites is correlated with histone modifications implicated in transcriptional activation, such as increase in acetylated histone marks (Zheng et al., 2009) (Figure 2). These studies on the mechanism of action of NRSF/REST in repressing neuron-specific genes illustrate how transcription factors can influence epigenetic processes by recruiting specific enzymatic activities to target loci.

Figure 2. Schematic model of regulation of gene expression by REST/NRSF.

In embryonic stem cells, REST/NRSF is associated with RE1-containing sequences and assures silencing of target genes by tethering repressive components, including HDAC1/2, LSD1, G9a, Suv39h1, CtBP, MeCP2 and Brg1 among others. During differentiation towards neuronal cell fate, the REST protein level is dramatically reduced via several mechanisms such as direct proteosomal degradation of the protein as well as via transcriptional repression and miRNA-dependent degradation of the mRNA. Remaining low levels of REST/NRSF protein are excluded from nucleus through interaction with Huntingtin.

Long-range interactions

An additional layer of regulatory complexity in transcription depends on long-range interactions in the genome that can be profiled genome-wide by chromatin conformation capture techniques integrated with deep-sequencing (de Wit and de Laat, 2012) (Table I). The original 3C assay tests the interaction between two known distal genomic regions. In a recent study, circular 3C (or 4C), which is a 3C variant that detects physical interactions between a known bait with unknown distal regions, was employed to explore the in vivo dynamics of the three-dimensional architecture of the Hox gene clusters, which are expressed in a spatial and temporal manner during body axis development in vertebrates (Noordermeer et al., 2011). Aligning the long-range interactions detected by 4C with the repressive H3K27me3 and active H3K4me3 histone marks, the authors showed that inactive Hox genes (e.g., those silenced in forebrain) are organized in a single repressive three-dimensional domain, while active Hox genes (e.g., those transcribed in anterior or posterior trunk tissues) are organized in three-dimensional domains that are bimodal (H3K4/K27-me3) and transcriptionally active (Noordermeer et al., 2011), suggesting that genome architecture may be involved in regulating gene expression programs during development. Additionally, Dekker and collaborators mapped short and long-range interactions in the genome of several cell lines using chromosome conformation capture carbon copy (5C), which detects interactions between two targeted sets of genomic loci, such as transcription start sites (TSS) and distal regulatory elements. The authors found that there is a significant correlation between gene expression, promoter-enhancer interactions and the presence of eRNAs, further confirming the functional relationship among distal regulatory regions in the genome (Sanyal et al., 2012). Finally, the application of HiC (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009), which is a completely unbiased and open-ended 3C variant that does not predefine which interactions will be interrogated, was used to examine the three-dimensional architecture of the genome in several mouse and human cells types. This analysis reported that there are megabase-sized, highly stable and conserved “topological domains” throughout the genome, which are separated by boundary regions enriched in the zinc-finger protein CTCF and specific histone marks that constrain heterochromatin spreading, suggesting that mechanisms establishing higher order structures may be evolutionary conserved (Dixon et al., 2012).

Emerging concepts in DNA methylation and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms of neuronal function

DNA methylation is probably the most studied epigenetic mark in the field of neurobiology (Bird, 2002; Day and Sweatt, 2011). However, our understanding of the methylome (the genome-wide distribution of DNA methylation) has been redefined by recent studies combining ”traditional” techniques to identify DNA methylation and genome-wide-based approaches, licensed by deep sequencing (Harris et al., 2010; Laird, 2010). These studies have been instrumental in redefining some long held views on the stability, derivative forms, and functions of this mark. In particular, these techniques include assays to detect 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) using antibodies against methylated DNA (MeDIP-seq) or methyl binding proteins (MBD-seq); enzyme-digestion based assays (MRE-seq); and chemical conversion-based assays that distinguish methylated versus non-methylated cytosines (e.g. Bis-seq) (Table I).

One of the first examples of whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (Bis-seq) compared the methylome of human ESCs to IMR90 fibroblasts, along with their transcriptome and ChIP-seq analysis of histone marks (Lister et al., 2009). This study uncovered the diverse methylation landscape at nucleotide resolution and identified widespread differences in the composition and patterning of cytosine methylation between the two cell types, as well as features such as pervasive methylation on transcribed gene bodies, depletion from 5′UTRs, TSS and transcription termination sites, depletion of CG methylation at protein-DNA interaction sites and a surprising abundant fraction of non-CG methylation. A similar approach has since been applied to neuronal systems as well, for example, finding that non-CG methylation is also abundant in adult mouse brain and may play a role in imprinting (Xie et al., 2012).

Insights into the functions of methylation in the brain have also been obtained by application of affinity enrichment-based approaches that provide qualitative estimates of genome-wide methylation at a much lower cost than Bis-seq, such as MeDIP-seq (Jacinto et al., 2008) and MBD-seq (Serre et al., 2010). In particular, MeDIP-seq has recently been successfully employed to identify brain region-specific patterns of the methylome in post-mortem normal adult human brains, revealing that there are distinct differences in DNA methylation patterns between different brain regions, especially at intragenic CpG islands (CGIs) and CGI “shores”, near genes implicated in brain development and neurobiological function (Davies et al., 2012). Furthermore, in a recent study using a combination of MeDIP-seq and MRE-seq, it was discovered that in human brain samples, the majority of methylated CpG islands were shown to be in intragenic and intergenic regions associated with transcribed regions, as assessed by RNA-seq, whereas less than 3% of CpG islands in 5′ promoters were methylated. In addition, tissue-specific DNA methylation regulated intragenic promoter activity, leading to alternative transcripts expressed in a tissue- and cell type-specific manner, from distinct brain regions, thus supporting a role for intragenic methylation in regulating cell context-specific alternative promoters in gene bodies (Maunakea et al., 2010). These finding demonstrate that different cell types or tissues are characterized by distinct DNA methylation patterns and suggest that this epigenetic modification may play a direct role in establishing cell type-specific patterns of gene expression.

Our understanding of the role of DNA methylation in repression of imprinted genomic regions has also increased by the use of deep sequencing approaches. Imprinted regions are broad genomic domains, which are heavily methylated and transcriptionally repressed. Recently, Ren and colleagues utilized Bis-seq to identify new imprinted brain loci by comparing parents and offspring derived from breeding two different strains of mice (Xie et al., 2012). By generating an allelic methylation map, they discovered 55 imprinted CpGs clusters, which include 23 novel imprinted clusters, with some occurring on microRNAs genes, as well as abundant non-CpG methylation that can be allele specific. These results may provide a basis to further understand the mechanisms of imprinting and allele specific gene expression. Moreover, the authors observed that the adjacent sequence have a strong impact in determining DNA methylation suggesting an evolutionarily conserved sequence code controlling DNA methylation in the mammalian genomes.

Dynamics of DNA methylation and the new appreciation for de-methylation as regulatory mechanism in the brain

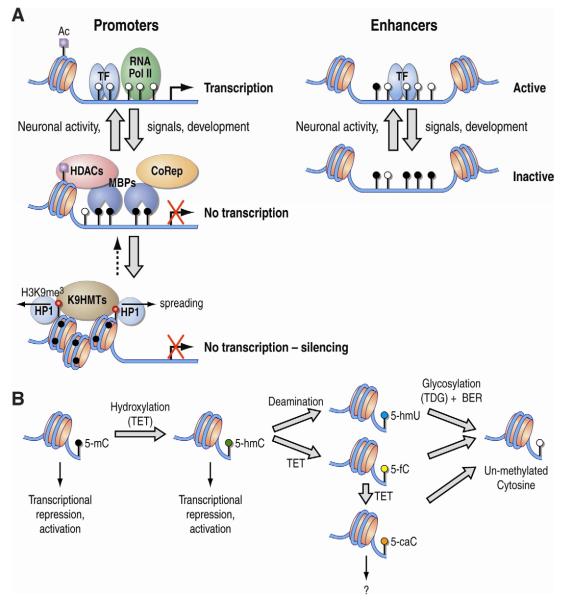

Until recently, DNA methylation had been considered a permanent, non-reversible epigenetic modification of DNA that could only be lost by a passive process due to consecutive cell divisions in the absence of DNA methyltransferase, Dnmt1, which is responsible for DNA methylation maintenance. However, DNA demethylation has garnered renewed interest since it now appears that active DNA-demethylation can occur by different enzymatic mechanisms including direct removal of the methyl group of 5-mC, base excision repair (BER) through direct excision of the 5-mC, deamination of 5-mC to T followed by BER of the T/G mismatch, nucleotide excision repair (NER), oxidative demethylation and radical SAM-based demethylation (Wu and Zhang, 2011; Wu and Zhang, 2010) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. A. Dynamics of DNA methylation.

DNA methylation changes can be brought about by diverse signals such as neuronal activity or during development. Active promoters are generally unmethylated (open circles) allowing the binding of transcription factors (TF), recruiting RNA polymerase (RNA Pol II) and other factors for transcription to occur. Upon methylation (closed black circles), Methyl binding proteins (MBPs) are recruited to promoters and recruit repressive machinery such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) and Corepressors (CoRep), which lead to reduced transcription. In some cases, further recruitment of other enzymes such as the H3K9HMT Suvar39h (K9HMTs), which deposit the H3K9me3 mark on histone tails, can lead to further repression by recruiting HP1, condensation of the chromatin, and spreading of the repressive state. Similarly, DNA methylation changes can occur on enhancers, which when unmethylated (open circles), allow the binding of transcription factors (TF) and other proteins required for enhancer activity. B. DNA methylation variants. A series of enzymes are capable of demethylating 5-methyl Cytosines (5-mC) to an unmethylated state, with various intermediates. TET1, a member of the Tet family of proteins, is a 5-mC dioxygenase responsible for catalyzing the conversion of 5-mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) and further to 5-formylcytosine (5-fC) and/or 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC). Alternatively, 5-hmC can be deaminated to 5-hydroxymethyluracil (5-hmU). These derivatives of 5-hmC can be further converted to an unmethylated state via various mechanisms such as glycosylation by TDG and the base excision repair machinery (BER). These various modifications highlight the newly found diversity and dynamics in the DNA methylation landscape; however, the precise roles of these modifications have yet to be determined. The suggested role of these modifications is described below each of them.

However, the biological implications of methylation dynamics have been addressed, until recently, predominantly in non-neuronal systems. In particular, DNA methylation levels can be dramatically reduced in response to ligand-dependant nuclear receptor signaling, suggesting that DNA demethylation may play a role in regulated gene expression, particularly in response to acute stimuli, such as upon hormone stimulation (Kim et al., 2009; Metivier et al., 2008). In neuronal models, recent genome-wide efforts have shown activity-dependent changes in DNA methylation in the brain. Song and colleagues used a single nucleotide MSCC sequencing based methodology (a variant of MRE-seq) to assay for changes in CpG methylation following synchronous activation of hippocampal dentate granule cells by electroconvulsive stimulation (Guo et al., 2011). The authors found that a subset of CpG dinucleotides from the ~200,000 CpGs assayed either gained or lost methylation after activity-dependent signals. The genes associated with the changes in CpG methylation were related to brain-specific genes and their expression was anti-correlated to increased methylation. Interestingly, a large proportion of the dynamically methylated CpGs were not associated with gene regions, raising the possibility that they might be associated either with the expression of non-annotated genes, such as ncRNAs or affecting distal genomic regulatory elements, rather than promoters or gene bodies directly, suggesting that neuronal activity-dependent changes in methylation may play a role in distal regulation of transcription, such as enhancers and/or insulators. This is supported by the observation that DNA methylation affects the level of transcription factor binding to the genome and that changes in DNA methylation have been directly observed at enhancer regions (Stadler et al., 2011; Thurman et al., 2012; Wiench et al., 2011). Schubeler and colleagues surveyed the methylome in ESCs and neural progenitor cells (NPCs) using Bis-Seq (Stadler et al., 2011). They found that while most CpGs in the genome were highly methylated, as expected, a small subset (~4%) showed low to intermediate levels of methylation, in the range of 10–50% methylation. These areas, coined “low methylated regions” (LMRs), were evolutionarily conserved, and were not found in CGIs, which were identified as regions of low CpG methylation. These regions contained chromatin marks that are characteristic of distal regulatory elements and function as enhancers in experimental assays. Moreover, when ESCs were differentiated to NPCs, new LMRs were formed adjacent to genes important for neuronal development. Thus, LMRs may define a subset of methylated regions that are dynamically changed, possibly through the recruitment of DNA binding transcription factors, allowing for highly localized changes in methylation during development in order to regulate specific gene transcription programs. Taken together, these provocative results suggest that methylation dynamics in the brain may be more common than previously anticipated and may serve as a mechanism to control gene expression in response to neuronal activity. However, the full spectrum of changes in methylation has yet to be characterized, and the response to other forms of neuronal activity needs yet to be explored.

5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) and other cytosine modifications emerging as new epigenetic modifications in development and disease

5-hmC is another product of the 5-mC demethylation process, and is emerging as an important epigenetic mark that is particularly enriched in brain regions, perhaps playing a role in development, aging and disease (Tan and Shi, 2012). The initial challenge for detecting 5-hmC was that bisulfite conversion could not discriminate between 5-mC and 5-hmC. This was recently overcome by pre-treating DNA with reagents that selectively modify the conversion properties of either 5-mC or 5-hmC in the bisulfite treatment. Several similar strategies allow the identification of 5-hmCs after subtracting the sequencing information obtained by this procedure compared to standard bisulfite procedure alone (OxBS-seq (Booth et al., 2012), TAB-seq (Yu et al., 2012) and 5-hmC-seq (Szulwach et al., 2011).

Using such approaches, 5-hmC was initially found in pluripotent cells (ESCs), but is about 10 fold more abundant in terminally differentiated cells, such as Purkinje neurons (Kriaucionis and Heintz, 2009). Studies using affinity-based approaches have demonstrated that 5-hmC is enriched at promoters, enhancers, CTCF-binding sites and gene bodies (particularly exons), suggesting a role in gene regulation. In fact, in a recent study, half of all 5-hmC modification sites observed in ESCs occurred in distal and chromatin accessible genomic sites, as mapped by ChIP-seq, DNase-Seq, and TAB-seq (Yu et al., 2012). This work also revealed strand asymmetry at 5-hmC sites, in contrast to 5-mC sites, and detected high levels of 5-hmC and reciprocally low levels of 5-mC near but not at cis-regulatory elements for transcription factors. While it is still unclear what the significance of these new DNA modifications will be, it is clear that in some instances genes known to be involved in brain function are tightly linked with such DNA modifications. For example, it has been shown that 5-hmC levels were inversely correlated with the dosage of MeCP2, which is a methyl-binding protein mutated in the autism spectrum disorder Rett syndrome (Szulwach et al., 2011). In this study, the levels of 5-hmC in Mecp2-null mice brains were shown to be increased mainly on gene bodies, and also that MeCP2 was able to block in vitro TET-dependent conversion of 5-mC to 5-hmC. However, at dynamically differential 5-hydroxymethylated regions, 5-hmC was reduced in the MeCP2 null brains, suggesting the role of MeCP2 in maintaining proper 5-hmC levels may be context dependent and that 5-hmC-mediated epigenetic modification may be critical in neurodevelopment and disease. This will still need to be further studied, since recent work has shown that indeed 5-hmC is primarily bound in the brain by MeCP2 and is associated with active transcription, but no change in 5-hmC levels were detected in MeCP2 null neurons (Mellen et al., 2012).

How do neurons “read” DNA methylation and interpret changes in levels of DNA methylation?

A wealth of data suggests that the ability to “read” DNA methylation is important for brain development and function. However, what are the mechanisms that are required to read this mark and in what way, and what are the consequences of not reading them correctly? Until recently, the most common outcome of DNA methylation demonstrated was transcriptional repression, especially when affecting promoter regions. One of the main mechanisms that impart this repression is through direct recognition of the methylated DNA by methyl binding proteins (MBDs), which recruit HDACs to deacetlyate histones. It can also further recruit other enzymes such as the H3K9 histone methyltransferase Suvar39h, which can lead to further repression by recruiting HP1 and spreading of the repressive state (Cheutin et al., 2003; Schotta et al., 2004), as well as the recruitment of DNMT1, which can further methylate adjacent DNA and lead to heterochromatization and more robust silencing of the region (Smallwood et al., 2007). This mechanism is known to occur in X chromosome inactivation (Sado et al., 2000) (Figure 3A). However, one of the most striking examples for the requirement to properly read the methylation mark is the autism spectrum disorder, Rett syndrome, in which mutations in a DNA methylation “reader,” MeCP2, causes widespread defects in neuronal maturation, leading to deficiencies in learning, behavior and seizures, and it is an example of a protein linking epigenetic and neuronal function (Guy et al., 2011; Moretti and Zoghbi, 2006). Alternatively, specific mutations in MeCP2 have been suggested to impair its ability to bind 5-hmC rather than 5-mC in the brain, leading to reduced transcriptional activity (Mellen et al., 2012).

Another example is in the case of imprinting, when one of the parental alleles must be silenced via a methylation mechanism in order to allow normal development. Aberrant imprinting of specific regions can cause severe mental retardation and autism, such as in Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome, where the imprinting control regions fail to be methylated, leading to aberrant expression and disease (Barlow, 2011; Chamberlain and Lalande, 2010).

Methylation of transcription factors binding site is another mechanism whereby the transcriptional response of cells can be epigenetically regulated by methylation. For example, CTCF, a factor known to function in transcriptional repression, insulator function and chromatin looping, fails to bind to its binding site when it is methylated, initially shown on the H19/Igf2 imprinting control region (Bell and Felsenfeld, 2000; Hark et al., 2000). More recently, the ENCODE effort estimated that 40% of variable CTCF binding is linked to differential methylation, mainly at two critical positions within the CTCF binding motif (Wang et al., 2012). Other examples include AP-2, which plays a critical role in regulating gene expression during early development (Comb and Goodman, 1990), and YY1, a protein that is involved in repressing and activating a diverse number of promoters (Kim et al., 2003; Tate and Bird, 1993). It may be possible that in addition to chromatin structure, methylation of transcription factor binding sites is a general mechanism by which cells epigenetically regulate which site will be “accessible” for binding at a given time and cell type, from the myriad of potential binding sites available in the genome (Choy et al., 2010). This raises the possibility that modulating the methylation landscape in a cell can contribute to modulating the pattern of transcription factor binding at a genome-wide scale. Conversely, it is also possible that the ability to methylate a transcription factor binding site might be dependent on the occupancy of that site by the specific factor, since it has been suggested that in cancer a major factor determining the ability to de-novo methylate specific sequence motifs at CpG islands is the absence of the cognate transcription factor (Gebhard et al., 2010). More recently, the ENCODE project compared methylation across 19 cell types using RRBS for which DNase I hyper-sensitivity data was also available, a measure of chromatin accessibility mostly due to regulatory factor binding (Neph et al., 2012; Thurman et al., 2012). Of ~35,000 DNAse I hypersensitivity sites that contained CpGs, 20% showed significant association between methylation and accessibility, predominantly indicating that increased methylation was negatively associated with accessibility. These analyses highlight the advantage of obtaining a genome-wide methylation map at single base pair resolution by restricting the potential cohort of regulating transcription factors of a given gene by suggesting those which have available (non-methylated) binding sites.

Taken together, although methylation has been studied extensively for many years, new sequencing based methodologies are facilitating new and exciting discoveries that are helping to redefine our understanding of the functions of this important epigenetic modification.

The epigenome in cognitive function and behavior

Epigenomic and transcriptomic signatures of brain plasticity

Accumulating lines of evidence have shown that crucial players of synaptic plasticity function as epigenetic regulators and that mutations and variations in their genes are linked to mental illnesses. Therefore, epigenomic and transcriptomic profiles may serve as signatures of physiological states and pathological stages. Different experimental approaches have been used to correlate neural plasticity with epigenetic control of gene expression. Indeed, activity-dependent gene expression responses (West and Greenberg, 2011), along with changes in post-translational modifications of histone tails such as acetylation, phosphorylation and methylation, have been observed in hippocampus-dependent memory formation in rodents (Bredy et al., 2007; Chwang et al., 2006; Fischer et al., 2007; Gupta et al., 2010). Taking advantage of ChIP-seq, Peleg and colleagues mapped the genome-wide pattern of acetylated histone marks in aging brain and showed that, surprisingly, H4K12Ac levels on gene bodies of “learning-associated genes” rose during associative learning, thus suggesting an epigenetic control of transcriptional elongation during memory formation (Peleg et al., 2010). Moreover, the authors demonstrated that Fmn2, a gene that encodes an actin regulatory protein and is required for normal memory formation, exhibits impaired transcription in aged mice together with reduced H4K12 acetylation, supporting the hypothesis that dysregulation of epigenetic mechanisms can be causally involved in cognitive decline.

Cognitive functions have also been correlated with the activity of histone-modifying enzymes. One of the best examples is the histone acetyltransferase CREB-binding protein (CBP), a protein encoded by a gene mutated in the Rubinstein-Taybi neurodevelopmental syndrome characterized by mental retardation (Petrij et al., 1995). Genetic mutations of the Cbp gene in mice impair memory formation and long-term potentiation (Alarcon et al., 2004). Similarly, HDACs are involved in the regulation of cognition. For example, overexpression of the Hdac2 gene in the hippocampus of mice negatively regulates synaptic plasticity and memory formation (Guan et al., 2009). Consistently, Hdac2 overexpression is detected in mouse models of neurodegeneration, as well as in Alzheimer’s disease patients, along with repression of genes implicated in learning and memory (Graff et al., 2012). In fact, pharmacological interventions that regulate epigenetic mechanisms in neurons, such as HDAC inhibitors, promote long-term potentiation, lead to the reactivation of learning-induced gene expression in the aging brain, and restore learning ability in mice exhibiting severe neurodegeneration (Fischer et al., 2007; Levenson et al., 2004; Peleg et al., 2010).

Histone methylation is also emerging as a central mechanism underlying cognitive functions. For example, genetic ablation of the histone H3K4 methyltransferase MLL1 interferes with consolidation of contextual fear memories (Gupta et al., 2010); and the postnatal neuron-specific deletion of the histone methyltransferase G9a/GPL in mice elicits cognitive and behavioral defects through deregulation of H3K9 methylation (Schaefer et al., 2009).

While mutations in genes encoding epigenetic regulators can be directly associated with distinct congenital disorders, psychiatric disorders are etiologically complex diseases involving both genetic predisposition and environmental factors. The lack of straightforward genetic causes together with the observation of long lasting gene expression changes in many affected individuals (Balu and Coyle, 2010) have prompted the hypothesis that epigenetic mechanisms may act as a “bridge” connecting the gap between genetic risk factors linked to major psychoses and autism (copy number variation, polymorphisms) and environmental events, such as stress, diet, drug exposure, and social behavior (Feil and Fraga, 2012). In fact, differences in both DNA methylation and histone marks have been observed in studies of postmortem human brain of individuals suffering these various diseases (Dempster et al., 2011; Mill et al., 2008). Moreover, genetic studies in mice implicate histone modifying enzymes in the regulation of affective behaviors, including the H3K9 methyltransferases SETDB1 (Jiang et al., 2010) and G9a/GLP (Schaefer et al., 2009), and the H3K4 methyltransferase SMCX (Tahiliani et al., 2007).

Taken together, these and other studies support the hypothesis that a fine-tuned regulation of chromatin signatures acts as a molecular mechanism tightly associated with neuronal plasticity and environmental adaptation. The challenge now will be to expand these studies with genome-wide approaches that may identify new association between the epigenome and behavioral traits in normal and diseased brain.

RNA dynamics and nuclear architecture may play a role in neuronal function and mental disorders

The regulatory functions of ncRNAs in the epigenetic control of transcription

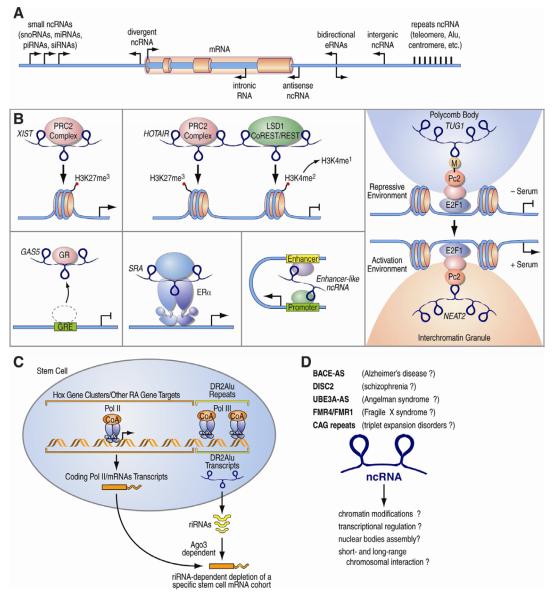

As previously mentioned, transcriptomic data generated by high-throughput sequencing methods have established that most of the genome is transcribed. However, the majority of expressed transcripts do not derive from coding genes, but from small and long non-coding genes or genomic sequences without apparently protein-coding potential. Intriguingly, many of these non-coding transcripts are far more than just transcriptional “noise” (Wang and Chang, 2011). Different sequencing-based assays have been developed to profile RNAs (Table I). Furthermore, genome-wide profiling of histone marks that are indicative of promoters or gene bodies also provides an unbiased strategy to identify ncRNAs. These assays have revealed an unexpected anatomy of genome organization, whereby ncRNAs can be transcribed from overlapping coding sequences, intergenic loci or highly specialized chromosomal regions (e.g., telomeres and centromeres) in both sense and antisense or bidirectional orientations (Figure 4A). Different sequencing-based assays to profile RNA molecules on a genome-wide scale have been developed (Table I). Small ncRNAs, including snoRNAs, miRNAs, piRNAs, siRNAs and Alu-derived RNAs, are highly conserved and generally mediate gene-silencing regulating mRNA stability and translation in a post-transcriptional manner (Holley and Topkara, 2011). Long ncRNAs, in contrast, do not show a high degree of sequence conservation and engage in a broad range of biological pathways acting as direct regulators of gene expression (Wang and Chang, 2011) (Figure 4B). Indeed, long ncRNAs can serve as molecular signatures of specific spatio-temporal, developmental and signal-specific events, as in the case of XIST, a ncRNA whose expression marks active silencing during X chromosomal inactivation (Zhao et al., 2008). Long ncRNAs can also function as “guides” to dictate chromatin states by targeting histone-modifying activities to specific loci either in cis or in trans, such as HOTAIR, which recruits Polycomb complex 2 (PRC2) and lysine demethylase LSD1 to specific genomic loci (Rinn et al., 2007; Tsai et al., 2010). Long ncRNAs can act in trans as molecular decoys sequestering specific DNA binding proteins, such as Gas5 that inhibits the action of the glucocorticoid receptor, GR (Kino et al., 2010). LncRNAs can also guide transcription factors, as in the case of the ncRNA SRA that co-activates nuclear receptors, including estrogen receptor (ERα), as part of a ribonucleoprotein complex (Cooper et al., 2011; Lanz et al., 1999). Additionally, lncRNAs can mediate short and long-range chromosomal interactions by connecting enhancer and promoter regions, thus functioning as enhancer-like elements despite being RNAs (Orom et al., 2010). Finally, lncRNAs can function as scaffold molecules to assemble subnuclear structures, such as MALAT1 and TUG1 (Yang et al., 2011). Therefore, some ncRNAs can be considered as functional molecular regulators comparable to proteins, and are likely to combine different mechanisms to achieve a specific biological function.

Figure 4. ncRNAs function in the brain.

A. Schematic illustration of various classes of RNA species derived by different genomic locations, including coding, short and long non-coding RNAs. Often lncRNAs are defined based on their location relative to the coding gene as divergent, antisense, intronic, and bidirectional. Intergenic lncRNAs are transcribed by separate transcriptional units. B. lncRNAs mechanisms of action: “guide” histone modifying enzymes to chromatin (XIST); scaffold molecules that bring together proteins complexes with different enzymatic activities (HOTAIR); “looping” of distant genomic regions through the recruitment of protein complexes (enhancer-like RNAs); inhibition of transcription factors binding to their cognate DNA motifs (GAS5); transcriptional activation by interacting with TFs; nucleation of nuclear structures (MALAT1) or “guide” of specific histone mark readers in distinct nuclear structures (TUG1). C. Model of RA-induced transcription of riRNAs in stem cells, where they target various mRNAs in an AGO3-dependent mechanism. D. Many lncRNAs have been linked to various neurological disorders, but their mechanism of action remains elusive.

ncRNAs as regulators of neuronal function and their link to disease

Increasing evidence has revealed the role of ncRNAs in regulating neural gene expression programs across the lifespan (McNeill and Van Vactor, 2012; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012). Many ncRNAs, especially miRNAs and lncRNAs, are highly enriched in the CNS and show precise temporal and spatial expression patterns in different developmental stages, brain regions, cell types, and subcellular localizations (Belgard et al., 2011; Kapsimali et al., 2007; Mercer et al., 2008). In particular, there are examples of ncRNAs that mediate epigenetic mechanisms in neural processes. For example, Rajasethupathy and colleagues, using a small RNA-seq approach, demonstrated that piRNAs levels are regulated during serotonin-induced long-term facilitation in the Aplysia CNS and modulate this synaptic plasticity event by inducing CpG methylation and silencing the expression of a key plasticity-related gene, CREB2 (Rajasethupathy et al., 2012). Another class of small ncRNAs, derived from Alu repeat elements, has been identified as the cause of a degenerative condition (Kaneko et al., 2011). Indeed, a deficiency in the miRNA regulator DICER1, which is observed in human patients affected by macular degeneration, is responsible for the accumulation of Alu transcripts in mice and, therefore, for their cytotoxic effect mediated by inflammatory responses (Tarallo et al., 2012). Alu-derived transcripts have also been associated with stem cell maintenance during retinoic acid (RA)-induced differentiation (Hu et al., 2012). Indeed, using bioinformatic analyses, it was found that 10% of Alu repeats in the human genome harbor nuclear receptor binding sites (Polak and Domany, 2006), including retinoic acid receptor (RAR). Hu and colleagues show that in ESCs retinoic acid induces the transcription of DR2-Alu elements leading to the AGO3-dependent generation of a new type of RA-induced small RNAs (riRNAs), which cause the degradation of mRNAs necessary to maintain the stem cell proliferative state that might be a crucial in neuronal differentiation. Whether Alu-derived transcripts induced by ligand-dependent nuclear receptors have a function in the brain will be a fascinating question to address (Figure 4C).

Several reports have raised provocative questions on the function of another class of repetitive elements, the retrotransposable elements LINE-1 (L1), which have been proposed to contribute to somatic mosaicism in the brain (Singer et al., 2010). These studies provide evidence of active retrotransposition of L1 during brain development and adult neurogenesis (Coufal et al., 2009; Muotri et al., 2005; Muotri et al., 2009). Subsequent studies also implicate the activity of L1 elements in brain disorders; particularly, Rett syndrome associated mutations have been shown to elevate the rate of transposition both in mice models of RTT and patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (Muotri et al., 2010). However, there is still controversy regarding the contribution of this mechanism to the brain’s genetic heterogeneity. Indeed, a recent finding, based on the amplification of single neuronal genomes from human brain, failed to detect significant somatic insertions by deep sequencing (Evrony et al., 2012).

Finally, different lncRNAs have been implicated in regulatory mechanisms of gene expression via different mechanisms in neurons. For example, RNA-seq analysis in cultured neurons showed that the expression of activity-dependent genes is correlated to bi-directional transcription of eRNAs, which are derived by nearby enhancer elements marked by H3K4Me1 and by the activity-induced binding of CBP and RNAPII, as detected by ChIP-seq (Kim et al., 2010). Whether eRNAs have a functional role in neuronal transcriptional regulation or establishment of neuronal chromatin states is yet to be determined. However, a recent report suggested a functional role for these ncRNAs in transcriptional regulation, showing that eRNAs, which are transcribed from enhancer elements bound by the transcription factor p53, are able to enhance transcription of neighboring p53 target genes in a RNA tethering reporter assay or by suppressing them via siRNAs (Melo et al., 2012). In this regard, the application of GRO-seq methodology might be of a great value to profile signal-dependent transcription of eRNAs (Core et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011).

Many lncRNAs have also been identified from loci associated with neurological and neurodegenerative disorders; however, their function remains elusive in most cases (Figure 4D). For example, lncRNA SCAANT1 derived from a triplet repeat expansion locus mutated in the spinocerebellar ataxia type 7 (Sopher et al., 2011); lncRNAs transcribed from the FMR1 locus associated to Fragile-X syndrome (Khalil et al., 2008); UBEA3-AS transcript linked to the Angelman syndrome (Lalande and Calciano, 2007); lncRNAs involved in neurodegenerative diseases, such as REST-dependent lncRNAs in Huntington’s disease (Johnson et al., 2009) or BACE-AS and 17A lncRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease (Faghihi et al., 2008; Massone et al., 2010); and DISC2 associated with psychiatric disorders (Chubb et al., 2008).

The advent of deep-sequencing methods has also provided an unprecedented tool to uncover novel functions of RNA-protein and RNA-DNA interactions. In respect to RNA-protein interactions, CLIP-seq and PAR-CLIP, which are two similar deep sequencing approaches, have been developed to profile the association of RNA-binding proteins to the transcriptome (Table I). Particularly in neurons, CLIP-seq of Nova, a neuron-specific splicing factor that is targeted by autoantibodies in brain tumors, led to the discovery that Nova regulates alternative polyadenylation of transcripts in the brain (Licatalosi et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2010). Similarly, CLIP-seq of FMRP, a protein encoded by a gene mutated in Fragile X syndrome, uncovered a new function for FMRP as a translational repressor capable of stalling ribosomal translocation (Darnell et al., 2011).

In respect to RNA-DNA interactions, the genome-wide binding profile of HOTAIR by ChIRP-seq, which is a method to profile the association of RNA molecules to the genome, revealed the important role of this lncRNA in silencing gene transcription by nucleating Polycomb complexes at specific genomic loci and facilitating the formation of repressive H3K27me3 regions (Chu et al., 2011). Given the abundance of lncRNAs in the brain and their known link to various neuronal functions, the application of this assay may be of particular value in the field of neurobiology.

Finally, another general theme emerging from multiple functional analyses of ncRNAs is their tendency to nucleate the assembly of multisubunit ribonucleoprotein complexes. For example, the lncRNA MALAT1, which is functionally essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles, controls synapse formation through regulating gene expression and alternative splicing in hippocampal neurons (Bernard et al., 2010). Interestingly, the lncRNAs MALAT1 and TUG1 are capable of guiding the relocation of signaling-induced genes from the silencing environment of Polycomb bodies to the transcriptionally active subnuclear compartment of interchromatin granules (Yang et al., 2011). It would be interesting to test whether neuronal activity could induce such a relocation strategy to regulate gene expression. It is not surprising, therefore, that alterations in nuclear organization have recently been linked to CNS diseases, such as laminopathies (Maraldi et al., 2011) and cohesinopathies (Liu and Krantz, 2009), or neurodegenerative disorders characterized by nuclear inclusions (Casafont et al., 2009). Indeed, it is now evident that gene regulation involves a complex genomic architecture organized in functional nuclear territories (Caudron-Herger and Rippe, 2012; Mao et al., 2011). Deep sequencing assays to profile the organization of the genome in the nuclear space could shed light on the underlying molecular mechanisms of these disorders. For instance, it will be interesting to decipher the network of chromosomal interactions induced by neuronal activity involving distant functional elements, such as CBP-regulated enhancers and promoters.

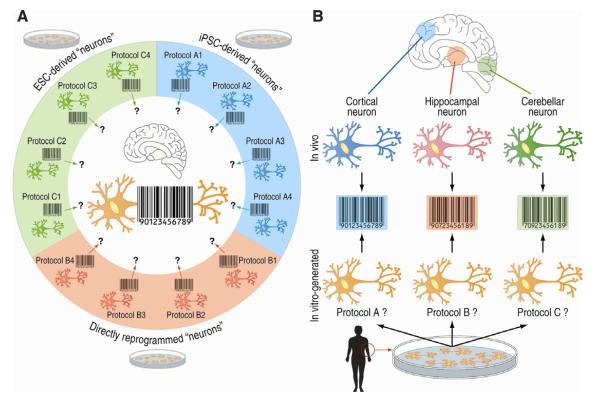

The value of the epigenome in the field of in vitro-generated neurons

In vitro-generated neurons are emerging as a valuable tool to study multiple aspects of neuronal function and disease. The classic approach to derive human neurons in vitro involves the differentiation of pluripotent ESCs into NPCs and then into neurons (Peljto and Wichterle, 2011). More recently, however, somatic cells have also been reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells, or iPSC (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al., 2007) and then differentiated into neurons (Brennand et al., 2011; Chamberlain et al., 2010; Ebert et al., 2009; Israel et al., 2012; Karumbayaram et al., 2009; Marchetto et al., 2010; Park et al., 2008; Pasca et al., 2011). Somatic cells can also be directly converted (or transdifferentiated) into NPC and/or neurons via transduction of neural-specific transcription factors and/or ncRNAs, or more recently via repression of a single RNA binding polypyrimidine-tract binding (PTB) protein (Ambasudhan et al., 2011; Caiazzo et al., 2011; Lujan et al., 2012; Pang et al., 2011; Pfisterer et al., 2011; Qiang et al., 2011; Ring et al., 2012; Son et al., 2011; Vierbuchen et al., 2010; Xue et al., 2013; Yoo et al., 2011). These new strategies have garnered extraordinary attention since they uniquely allow generation of neurons from patient-derived cells, which is expected to be particularly valuable in the study of neuronal disease, the development of personalized therapies and regenerative medicine in the future (Abdullah et al., 2012; Ronaghi et al., 2010; Young and Goldstein, 2012). We will not discuss these interesting aspects here since they fall beyond the scope of this Review. Instead, we propose to highlight how the use of new sequencing methodologies could help to assess a pertinent long-standing question in the neurobiology field; in particular, what defines the identity of a neuron and how does that relate to the vast neuronal diversity observed in the brain? In fact, the possibility of generating neurons by these different approaches, especially considering the multiple experimental protocols that have been reported, raises the intriguing technical question of whether all these variants are equivalent in generating similar types of cells. Arguably, this question needs to be addressed in order to determine to what extend in vitro-generated neurons can mimic the rich repertoire of neuronal diversity that exists in the brain. Since epigenetic regulators (writers, erasers, and readers) are key in “erasing” somatic epigenetic features and then “rewriting” new ones that define the reprogrammed state, we propose that a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the epigenome of in vitro-derived neurons and a direct comparison with the epigenome of endogenous neurons of the different regions of the brain can be instrumental in answering such questions, perhaps also contributing to harnessing the full clinical potential of these cells.

Using “epigenomic barcodes” to define neuronal identity

The challenge of generating a “neuron” does not end when reprogrammed cells show expected neuronal properties, since: 1) they should not concurrently show non-neuronal features; and, 2) they should not simultaneously show features of different neuronal subtypes. In fact, there are substantial physiological and morphological variations among neurons from different regions in the brain (Urban and Tripathy, 2012), which need to be accounted for when defining a neuron in vitro. We can certainly trace specific “biomarkers” and their neuronal functions to establish the identity of a neuron, but such an approach might not be sufficiently comprehensive considering the complexity of these cells and the mechanisms employed to generate them in vitro. Instead, genome-wide transcriptome and epigenome profiles may provide a more global assessment of the level of neuronal differentiation, transdifferentiation, or reprogramming. Transcriptomic profiles of steady-state mRNA (measured by either microarray or RNA-seq) have already been shown as highly valuable for identifying neuronal subtypes (Hawrylycz et al., 2012), and in the future even more if complemented with profiles of RNA undergoing transcription (measured by GRO-seq) and translation (measured by Ribo-seq) (Table 1 and Figure 1). In fact, RNA profiles undergoing translation have been already exploited in the identification of region-specific neuronal signatures, which is exemplified by an ongoing collaborative effort at the Rockefeller University for the development of the Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification (TRAP) methodology, which is an elegant genetic approach that enables the expression of an EGFP-tagged ribosomal protein in a particular cell population of the mouse brain and, therefore, the isolation of polyribosomes and the profiling of associated mRNAs only from the cell population of interest (Doyle et al., 2008; Heiman et al., 2008). Such a strategy has the potential to overcome the technical limitations associated with isolating and characterizing region-specific neurons within the large complexity of cell types in the brain. However, transcriptome profiles may fail to provide key identity information that is only harbored by the epigenome, such as some cell fate features (Garrison et al., 2007) and the depth of identity resetting when neurons are generated in vitro. In this regard, a recent comparison of iPSCs and the original somatic cells revealed that the reprogrammed cells maintain epigenetic features that are reminiscent of their origin, or contain new features that result from the reprogramming process itself (Lister et al., 2009) (Marro et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2011). The epigenome may also provide information for neuronal identity and diversity via enhancer profiles. For example, a recent profile of enhancer-specific histone marks showed robust patterns that were distinctive of cortex, cerebellum, olfactory bulb and E14.5 brain regions (Shen et al., 2012). Other studies have similarly shown DNA methylation profiles distinctive of different brain regions (Davies et al., 2012; Ladd-Acosta et al., 2007; Maunakea et al., 2010). Therefore, histone marks and DNA methylation patterns are valuable ‘barcodes’ of neuronal identity and diversity, which could be exploited to elucidate similarities and differences between the epigenome of in vitro-generated neurons and neuronal subtypes by the different protocols available to generate these cells. With a parallel comprehensive analysis of endogenous neurons from different regions in the brain (as similarly done in the analysis of the transcriptome), it may now be possible to determine which strategy most faithfully generates a neuron that best resembles its endogenous counterpart (Figure 5). Obviously, these aspects represent enormous challenges since it is unclear to what extend all neuronal subtypes have been identified, and if current experimental approaches can efficiently and unambiguously isolate these subtypes.

Figure 5. The epigenome to assess neuronal identity of reprogrammed cells.

A. There are three common strategies to generate a neuron in vitro (differentiated from ESCs, iPSCs, or directly transdifferentiated from somatic cells), and each might be accomplished by different protocol variants (represented as 1-4). However, it remains unclear how similar is the level of conversion, efficiency, and reproducibility to the neural lineage between them, and which is the most similar to endogenous neurons (center of the image). Since transcriptomes may miss some identity features that epigenomes reveal, we propose a systematic use of the second as potential “barcodes” to establish the most appropriated protocol. B. Neurons show an especially high identity diversity or heterogeneity, a systematic effort of epigenetic profiling might be a useful tool to catalog and distinguish between these different identities. Furthermore, such catalogs may facilitate the search and identification of the best protocols to generate these different identities in vitro (bottom).

In summary, the profiling of the epigenome might provide a more comprehensive profile of the identity of an in vitro-generated neuron compared to the assessment of a limited number of neuronal traits. It may also help to establish which protocol derives neurons with the best fidelity to endogenous neuronal subtypes and which minimizes the residual effects of the conversion process. If performed systematically and comprehensively, these analyses may likely facilitate our future understanding of the neuron and facilitate the application of in vitro-generated cells in both the basic science and clinical arenas, perhaps minimizing potential future controversies caused by use of differential methodologies and mitigating risks when applied to potential therapies.

Challenges in the future of deep sequencing

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing approaches, particularly when combined with analyses of epigenetic processes, have now allowed us to: 1) classify and/or ascribe potential regulatory functions to vast sections of the genome, many of which were previously considered “junk,” 2) uncover the considerable cell type specificity of enhancer profiles and the predominance of these elements over promoters as the drivers of cell identity; 3) consider a redefinition of what constitutes a functional gene unit, since many enhancers and even promoters interact in the three dimensional nuclear space for proper gene expression; 4) identify a multitude of new ncRNAs in addition to the protein-coding transcripts; and, 5) particularly in neurons, to identify the importance of epigenomic mechanisms in neuronal function, identity, diversity, in vitro-generation and in disease.

The avalanche of new data that has accompanied these new discoveries has also raised some important questions: What is the conceptual difference between a promoter and an enhancer, since both regions bind transcriptional regulatory proteins and generate RNA transcripts? How can gene promoters be assigned to their respective regulating enhancers? What are the rules governing the promoter-enhancer interactions as well as interactions between other distal regulatory elements? Exactly how and to what extent does the three-dimensional organization of the nucleus exert a regulatory function on gene expression? How long are the dynamic epigenetic changes, induced by brain activity, maintained or propagated? To what extent are they required for proper neuronal function? What is the variation in these changes when probed at the level of single neurons and are such differences based on stochastic or predefined mechanisms? In this respect, new developments in single-cell sequencing methodologies have already allowed us to amplify genomes of single neurons to assess the genomic diversity of human brains (Evrony et al., 2012).

While the value of current and developing deep sequencing-based approaches is undeniable, there are still substantial technical and analytical challenges associated with their application (Kircher and Kelso, 2010). For example, differences in reagents and sequencing platforms can lead to certain biases that may give rise to differential results and complicate comparisons between separate studies. There is also the significant computational challenge of uniformly analyzing and effectively sharing deep sequencing data, and the financial burden for scientific programs worldwide that is associated with the massive production and maintenance of these datasets. However, arguably the biggest challenge of all is how to effectively mine the vast information derived from deep sequencing data. Computational and systems biology scientists clearly must play a major role in the discovery process, devising computational tools and increasing the accessibility to sequencing based data. The continuing discovery of additional histone and DNA modifications and their respective distributions in the genome, and the continuing ingenious application of sequencing technologies to biological questions, will undoubtedly provide fertile ground for further research into their function.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to those researchers whose important work we were not able to cite because of space limitations. The authors would like to thank J. Hightower for assistance in figure preparation, and R. Pardee for assistance in the editing and proofreading of the manuscript. Work from our laboratory was supported by grants from NINDS and NIDKK to MGR. F.T is supported by a Fellowship from the John Douglas French Alzheimer Disease’s Foundation. I.G.B. is a Liz Tilberis Scholar (Estate of Agatha Fort, OCRF). M.G.R. is an HHMI Investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdullah AI, Pollock A, Sun T. The path from skin to brain: generation of functional neurons from fibroblasts. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;45:586–595. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8277-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon JM, Malleret G, Touzani K, Vronskaya S, Ishii S, Kandel ER, Barco A. Chromatin acetylation, memory, and LTP are impaired in CBP+/− mice: a model for the cognitive deficit in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome and its amelioration. Neuron. 2004;42:947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambasudhan R, Talantova M, Coleman R, Yuan X, Zhu S, Lipton SA, Ding S. Direct reprogramming of adult human fibroblasts to functional neurons under defined conditions. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balu DT, Coyle JT. Neuroplasticity signaling pathways linked to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:848–870. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DP. Genomic imprinting: a mammalian epigenetic discovery model. Annual review of genetics. 2011;45:379–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgard TG, Marques AC, Oliver PL, Abaan HO, Sirey TM, Hoerder-Suabedissen A, Garcia-Moreno F, Molnar Z, Margulies EH, Ponting CP. A transcriptomic atlas of mouse neocortical layers. Neuron. 2011;71:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AC, Felsenfeld G. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 2000;405:482–485. doi: 10.1038/35013100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard D, Prasanth KV, Tripathi V, Colasse S, Nakamura T, Xuan Z, Zhang MQ, Sedel F, Jourdren L, Coulpier F, et al. A long nuclear-retained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. EMBO J. 2010;29:3082–3093. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Birney E, Dunham I, Green ED, Gunter C, Snyder M. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16:6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth MJ, Branco MR, Ficz G, Oxley D, Krueger F, Reik W, Balasubramanian S. Quantitative sequencing of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine at single-base resolution. Science (New York, NY. 2012;336:934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1220671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredy TW, Wu H, Crego C, Zellhoefer J, Sun YE, Barad M. Histone modifications around individual BDNF gene promoters in prefrontal cortex are associated with extinction of conditioned fear. Learn Mem. 2007;14:268–276. doi: 10.1101/lm.500907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennand KJ, Simone A, Jou J, Gelboin-Burkhart C, Tran N, Sangar S, Li Y, Mu Y, Chen G, Yu D, et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;473:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiazzo M, Dell’Anno MT, Dvoretskova E, Lazarevic D, Taverna S, Leo D, Sotnikova TD, Menegon A, Roncaglia P, Colciago G, et al. Direct generation of functional dopaminergic neurons from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nature. 2011;476:224–227. doi: 10.1038/nature10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casafont I, Bengoechea R, Tapia O, Berciano MT, Lafarga M. TDP-43 localizes in mRNA transcription and processing sites in mammalian neurons. J Struct Biol. 2009;167:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudron-Herger M, Rippe K. Nuclear architecture by RNA. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SJ, Chen PF, Ng KY, Bourgois-Rocha F, Lemtiri-Chlieh F, Levine ES, Lalande M. Induced pluripotent stem cell models of the genomic imprinting disorders Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17668–17673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004487107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SJ, Lalande M. Neurodevelopmental disorders involving genomic imprinting at human chromosome 15q11-q13. Neurobiology of disease. 2010;39:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheutin T, McNairn AJ, Jenuwein T, Gilbert DM, Singh PB, Misteli T. Maintenance of stable heterochromatin domains by dynamic HP1 binding. Science (New York, NY. 2003;299:721–725. doi: 10.1126/science.1078572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy MK, Movassagh M, Goh HG, Bennett MR, Down TA, Foo RS. Genome-wide conserved consensus transcription factor binding motifs are hyper-methylated. BMC genomics. 2010;11:519. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, Artandi SE, Chang HY. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol Cell. 2011;44:667–678. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb JE, Bradshaw NJ, Soares DC, Porteous DJ, Millar JK. The DISC locus in psychiatric illness. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:36–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwang WB, O’Riordan KJ, Levenson JM, Sweatt JD. ERK/MAPK regulates hippocampal histone phosphorylation following contextual fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2006;13:322–328. doi: 10.1101/lm.152906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comb M, Goodman HM. CpG methylation inhibits proenkephalin gene expression and binding of the transcription factor AP-2. Nucleic acids research. 1990;18:3975–3982. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Vincett D, Yan Y, Hamedani MK, Myal Y, Leygue E. Steroid Receptor RNA Activator bi-faceted genetic system: Heads or Tails? Biochimie. 2011;93:1973–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core LJ, Waterfall JJ, Lis JT. Nascent RNA sequencing reveals widespread pausing and divergent initiation at human promoters. Science. 2008;322:1845–1848. doi: 10.1126/science.1162228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coufal NG, Garcia-Perez JL, Peng GE, Yeo GW, Mu Y, Lovci MT, Morell M, O’Shea KS, Moran JV, Gage FH. L1 retrotransposition in human neural progenitor cells. Nature. 2009;460:1127–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature08248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]