Abstract

The renal manifestations of patients infected with HIV are diverse. Patients may have podocytopathies ranging from a minimal-change–type lesions to FSGS or collapsing glomerulopathy. Furthermore, such patients produce a variety of autoantibodies without clinical signs of the disease. Antiretroviral drugs also cause renal injury, including crystals and tubular injury, acute interstitial nephritis, or mitochondrial toxicity. In these circumstances, it is essential to perform a renal biopsy for diagnosis and to guide treatment. Here we describe a patient with HIV who presented with AKI and hematuria without concomitant systemic manifestations. Renal biopsy elucidated the cause of acute deterioration of kidney function.

The renal manifestations of patients infected with HIV are diverse (Table 1). The most common histologic type of glomerular disease is HIV-associated nephropathy. A variety of other glomerular diseases occur to a lesser degree, including various immune-complex glomerulonephritides, such as membranous nephropathy, IgA nephropathy, membranoproliferative GN, lupus-like nephritis, and cryoglobulinemia, or amyloidosis and minimal change disease.1 Acute kidney injury (AKI) may relate to drug effects, thrombotic microangiopathy, or ischemic or toxic acute tubular injury.2

Table 1.

Major renal diseases associated with HIV infection

| Category | Major Renal Diseases Associated with HIV Infection |

|---|---|

| Glomerular | HIV-associated nephropathy, FSGS, IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, membranoproliferative GN, minimal change disease, thrombotic microangiopathy |

| Tubular | Crystal nephropathy, acute tubular injury, Fanconi syndrome, diabetes insipidus |

| Interstitial | Interstitial nephritis |

Clinical History

A 42-year-old man presented with malaise and 101°F temperature of 1 week’s duration, lower back and abdominal pain, hematuria, and nausea and vomiting of 1 day’s duration. His medical history included AIDS (current CD4+ count of 679 cells/ml) and previously treated AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. His medications included emtricitabine, tenofovir, and efavirenz. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 100.7°F and BP of 124/78 mmHg. His lungs were clear to auscultation, his abdomen was mildly tender to palpation in the left lower quadrant, but he had no lower-extremity edema. Laboratory studies revealed a serum creatinine (SCr) of 1.89 mg/dl, increased from 1.0 mg/dl 2 months earlier. Dipstick urinalysis revealed large blood and 10 mg of protein per dl, and urine microscopy showed 166 red blood cells (RBCs)/high-power field but no RBC casts or dysmorphic RBCs. Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 891 mg/mg. The patient was admitted for further assessment of his AKI. His ESR was 84 mm/hr (normal, 0–15 mm/hr), and the C-reactive protein level was 233.5 mg/L (normal, 0–10 mg/L). Results of tests for antinuclear antibody, ANCA, rheumatoid factor, serum complement levels, and antibodies to hepatitis B and C virus were negative. On hospital day 3, the patient’s SCr was 2.5 mg/dl, and he was treated with methylprednisolone. On hospital day 4, a percutaneous renal biopsy was performed.

Kidney Biopsy

The initial 13 slides sectioned for standard light microscopy revealed only two intact glomeruli with focal intense interstitial inflammation and tubulitis with focal eosinophils, suggesting a diagnosis of acute interstitial nephritis. However, a small area of necrosis was present in one of these areas, with two adjacent arterioles suggesting the inflammation could be due to a destructive glomerular process. There was no global or segmental sclerosis. Mesangial matrix and cellularity were normal, and there was no endocapillary proliferation or spikes or double contours of glomerular basement membranes (GBMs). Three glomeruli showed segmental fibrinoid necrosis with GBM breaks. One of these also had a cellular crescent with disruption of the Bowman capsule and inflammation and hemorrhage in the adjacent interstitium (Figure 1); one glomerulus had a cellular crescent only. There was about 5% interstitial fibrosis with proportional tubular atrophy. Extensive acute tubular injury was seen, with 70%–80% of tubular profiles showing apical/luminal blebs and cytoplasmic vacuolization, with rare RBC casts, but without microcystic changes. Arterioles and interlobular arteries were unremarkable, without vasculitis.

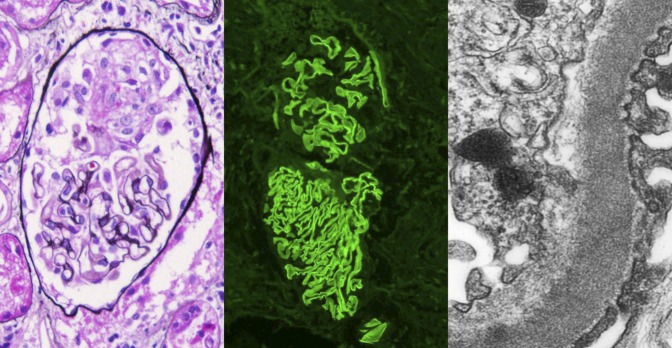

Figure 1.

Crescentic GN with linear GBM staining on immunofluorescence. There is a small cellular crescent with fibrinoid material, with no proliferation or sclerosis of the glomerular tuft (left panel, Jones silver stain; original magnification ×400). By immunofluorescence, there is linear staining along the GBM with antibody to IgG. The top glomerulus also shows a small cellular crescent (middle panel, anti-IgG immunofluorescence; original magnification ×200). By electron microscopy, a high-power view of the capillary wall shows intact foot processes (right), and no deposits were present in a subepithelial or subendothelial location. Reticular aggregates were present in the endothelial cell cytoplasm, consistent with high interferon levels in this HIV-positive patient (transmission electron microscopy; original magnification ×8000).

Immunofluorescence revealed two glomeruli: one with a crescent and both with linear GBM staining for IgG and κ in 3+ intensity (scale, 0–3+), with 1–2+ C3 and λ in the same pattern. There was no staining for IgA, IgM, or C1q. No nuclear or tubular basement membrane staining was seen.

Electron microscopy revealed one glomerulus with an early cellular crescent with fibrin tactoids without immune complex deposits, with only about 10% podocyte foot process effacement; thus, the findings did not indicate podocytopathy. Endothelial cells showed rare reticular aggregates, consistent with the patient’s HIV-positive status. Cells of proximal tubules demonstrated reduced formation of microvilli, but tubular mitochondria were unremarkable.

The final diagnosis was anti-GBM antibody–mediated necrotizing crescentic GN. There was no evidence of HIV-associated nephropathy or immune complexes or drug toxicity.

Clinical Follow-up

After the biopsy, additional laboratory data revealed an anti-GBM titer of 366 AU/ml (reference value, 0–25 AU/ml). SCr on day 4 was 4.5 mg/dl, and the patient was treated with plasmapheresis for 14 days, oral cyclophosphamide, and pulse intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone. On hospital day 7, his serum SCr was 6.2 mg/dl and hemodialysis was initiated.

He was subsequently admitted 1 month later with dyspnea ultimately thought to be due to volume overload and pulmonary manifestations of anti-GBM disease. His anti-GBM antibody titers were 104 AU/ml, and he was restarted on plasmapheresis. A month later, he was admitted with multifactorial pancytopenia in the presence of Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus viremia and prior treatment with myelosuppressive prophylactic antibiotics. At 7 months after the renal biopsy, he continues to undergo peritoneal dialysis but is free of markers of disease activity, with plans to be considered for renal transplantation.

Discussion

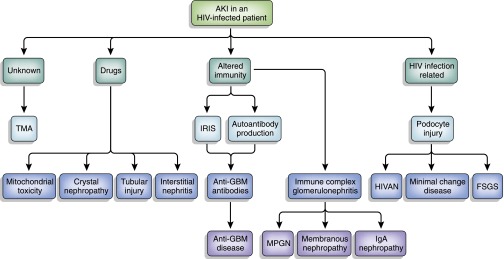

This case demonstrates the importance of performing renal biopsy in an HIV-infected patient with renal dysfunction. AKI in an HIV-infected patient can represent a variety of causes with different implications for management (Figure 2). AKI was initially thought to be due to a combination of volume depletion and nephrotoxicity from the patient’s antiretroviral therapy. We were surprised to identify anti-GBM disease on the kidney biopsy specimens, with subsequent positivity for anti-GBM antibodies in the serum. To our knowledge, only three cases of HIV infection and concomitant anti-GBM disease have been reported.3–5 Each case had a different presentation, course of treatment, and clinical outcome (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Schema of pathophysiologic mechanisms of AKI in HIV-positive patients. HIVAN, HIV-associated nephropathy; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; MNGN, membranoproliferative GN; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy.

Table 2.

Cases of anti-GBM GN in HIV-infected patients

| Study (Reference) | Age (yr) | Sex | CD4 Count (cells/ml) | Organs | SCr (mg/dl) | Renal Pathology | Treatment | Outcome | Anti-GBM Level | Complications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | ||||||||||

| Monteiro et al. (3) | 30 | Male | 495 | Kidney | 13.5 | Necrotizing crescentic (50%) GN | PLEX × 14 d Corticosteroidsa Cyclophosphamide, 1.5 mg/kg per d | ESRD | 68 U/ml | NA | NA |

| Wechsler et al. (4) | 55 | Male | 305 | Kidney | 3.5 | Necrotizing crescentic (10%) GN | PLEX × 14 d Corticosteroidsb | Resolution | 8.6 EU/mlc | 0 EU/ml | Nausea, vomiting, hematemesis |

| SCr 1.1 mg/dl 6 wk after treatment | |||||||||||

| IgA nephropathy | MMF IVIG Rituximab × 4 wk | ||||||||||

| Singh et al. (5) | 33 | Male | 214 | Kidney | 19.3 | Necrotizing crescentic GN | PLEX × 5 d | ESRD | 361 AU/ml | 40 AU/ml | Hypoxia (atypical pneumonia versus hemorrhage) |

| Lung | ATN | Corticosteroidsd | |||||||||

| Current report | 42 | Male | 679 | Kidney | 1.89 | Necrotizing crescentic GN | PLEX × 14 d Corticosteroidse Cyclophosphamide, 100 mg/d | ESRD | 366 AU/mlf | 104 AU/ml | EBV and CMV viremia |

SCr, serum creatinine; anti-GBM pre and post, anti-GBM antibody titers before and 4 wk after treatment; PLEX, plasmapheresis; NA, not available; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; ATN, acute tubular necrosis;

1 mg/kg per day.

40 mg/d.

Reference values, 0–5 EU/ml.

Methylprednisone, 1000 mg/d × 3 d; IVIG, 140 g (10% solution); rituximab, 375 mg/m2 per wk × 4 wk.

Methylprednisolone, 750 mg/d × 1 d, 500 mg/d × 1 day, 250 mg/d × 1 day, then prednisone, 80 mg/d × 5 d, then 60 mg/d.

Reference values, 0–19 AU/ml.

Antibody formation to the GBM has been linked to a conformational change in quaternary structure of the α-345 noncollagenous-1 (NC1) hexamer.6 It has been hypothesized that the formation of anti-GBM antibodies represents an autoimmune phenomenon in which an environmental factor, such as cigarette smoking or other disease processes with renal manifestations, may cause such a conformational change that exposes hidden antigen to the immune system. It has been proposed that CD4 T cells that are autoreactive to the α-3NC1 domain escape thymic deletion and may contribute to autoantibody formation.7 Several cases of membranous nephropathy or ANCA vasculitis associated with additional anti-GBM antibody formation and disease have been reported.8,9 ANCA antibodies may occasionally be produced before anti-GBM antibody formation and clinical disease.10

HIV infection presents an additional level of complexity in anti-GBM disease. HIV-infected individuals produce a variety of antibodies thought to be due to dysregulation of humoral immunity.11 Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is a complication that may occur after initiation of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Most cases appear during the first 3 months of therapy; however, some can present as late as 2 years after start of therapy.12 Although this is usually associated with worsening of preexisting or subclinical infections, autoimmune thyroiditis and Graves disease appearing shortly after institution of HAART have been reported.13 It is possible that HIV infection of the glomerular capillaries or podocytes causes endothelial or podocyte injury, leading to damage to of the underlying GBM and revealing the antigen described above to individuals who are predisposed to autoantibody formation. This may explain the appearance of anti-GBM antibodies in 17% of HIV-infected patients.11 Our patient presented with a fever after having received HAART for years. It is unclear whether this represented immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; however, one can clearly see that careful interpretation of autoantibodies in HIV-infected patients with renal disease is warranted and demonstrates the value of a renal biopsy in such circumstances.

Not all patients with HIV and circulating serum anti-GBM antibodies have clinical anti-GBM disease. Some patients with Alport syndrome develop anti-GBM antibodies after renal transplantation, but not all patients who develop antibodies develop anti-GBM disease.14 Thus, even with a positive serologic test result, a renal biopsy may be necessary to investigate whether the antibody has damaged the kidney. Szczech et al. demonstrated the importance of a renal biopsy in three HIV-infected patients with circulating serum anti-GBM antibodies.15 Each patient presented with clinically significant renal disease and positivity for anti-GBM antibodies in the serum, but the renal biopsies did not show characteristic findings of anti-GBM disease. Two of the three patients had adequate biopsy samples. One showed HIV-associated nephropathy with moderate glomerular staining for IgM and C3 in a mesangial pattern on immunofluorescence, and the other showed membranous nephropathy with no findings suggestive of anti-GBM disease on immunofluorescence. All three patients recovered renal function and were spared treatment for anti-GBM disease. Our patient had an atypical presentation for anti-GBM disease, including lack of pulmonary symptoms. The renal biopsy in this case was thus essential to diagnosis and management of this life-threatening illness.

Besides aiding in an appropriate diagnosis, the renal biopsy can help guide treatment. Standard therapy for anti-GBM disease includes plasmapheresis in combination with steroids and cyclophosphamide. Immunocompromised status can further complicate treatment. In the reported cases, only one developed hypoxia due to a possible atypical pneumonia.5 Our patient developed cytomegalovirus viremia with pancytopenia, presumably as a result of therapy. Once again, obtaining tissue for accurate diagnosis provides value to managing patients with HIV and anti-GBM antibodies. It has the potential to spare harmful treatment and the associated adverse effects and also guide treatment to ultimately preserve organ function.

Disclosures

None

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Wearne N, Swanepoel CR, Boulle A, Duffield MS, Rayner BL: The spectrum of renal histologies seen in HIV with outcomes, prognostic indicators and clinical correlations. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 4109–4118, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine DM, Fogo AB, Alpers CE: Thrombotic microangiopathy and other glomerular disorders in the HIV-infected patient. Semin Nephrol 28: 545–555, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monteiro EJB, Caron D, Balda CA, Franco M, Pereira AB, Kirsztajn GM: Anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis in an HIV positive patient: Case report. Braz J Infect Dis 10: 55–58, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wechsler E, Yang T, Jordan SC, Vo A, Nast CC: Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease in an HIV-infected patient. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 4: 167–171, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh P, Barry M, Tzamaloukas A: Goodpasture’s disease complicating human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Nephrol 76: 74–77, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedchenko V, Bondar O, Fogo AB, Vanacore R, Voziyan P, Kitching AR, Wieslander J, Kashtan C, Borza DB, Neilson EG, Wilson CB, Hudson BG: Molecular architecture of the Goodpasture autoantigen in anti-GBM nephritis. N Engl J Med 363: 343–354, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salama AD, Chaudhry AN, Ryan JJ, Eren E, Levy JB, Pusey CD, Lightstone L, Lechler RI: In Goodpasture’s disease, CD4(+) T cells escape thymic deletion and are reactive with the autoantigen alpha3(IV)NC1. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1908–1915, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basford AW, Lewis J, Dwyer JP, Fogo AB: Membranous nephropathy with crescents. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1804–1808, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clyne S, Frederick C, Arndt F, Lewis J, Fogo AB: Concurrent and discrete clinicopathological presentations of Wegener granulomatosis and anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 1116–1120, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olson SW, Arbogast CB, Baker TP, Owshalimpur D, Oliver DK, Abbott KC, Yuan CM: Asymptomatic autoantibodies associate with future anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1946–1952, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez GT, Critchfield JM, Rodriguez RA: Interpretation of serologic tests in an HIV-infected patient with kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 708–712, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French MA, Meintjes G: Disorders of immune reconstitution in patients with HIV infection. In: Infectious Diseases, edited by Cohen J, Opal SM, Powderly WG, 3rd Ed., Philadelphia, Elsevier Limited, 2010, pp 975–980 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jubault V, Penfornis A, Schillo F, Hoen B, Izembart M, Timsit J, Kazatchkine MD, Gilquin J, Viard JP: Sequential occurrence of thyroid autoantibodies and Graves’ disease after immune restoration in severely immunocompromised human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 4254–4257, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson BG, Tryggvason K, Sundaramoorthy M, Neilson EG: Alport’s syndrome, Goodpasture’s syndrome, and type IV collagen. N Engl J Med 348: 2543–2556, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szczech LA, Anderson A, Ramers C, Engeman J, Ellis M, Butterly D, Howell DN: The uncertain significance of anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody among HIV-infected persons with kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 48: e55–e59, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]