Abstract

Objective

This study assessed the micro-morphological changes in demineralized dentin scaffold following incubation with recombinant dentin matrix protein 1 (rDMP1).

Design

Extracted human molar crowns were sectioned into 6 beams (dimensions: 0.50 × 1.70 × 6.0 mm), demineralized and incubated overnight in 3 different media (n = 4): rDMP1 in bovine serum albumin (BSA), BSA and distilled water. Samples were placed in a chamber with simulated physiological concentrations of calcium and phosphate ions at constant pH 7.4. Samples were immediately processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) after 1 and 2 weeks.

Results

Analysis of the scaffold showed that decalcification process retained the majority of endogenous proteoglycans and phosphoproteins. rDMP1 treated samples promoted deposition of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) precursors and needle shaped hydroxyapatite crystals surrounding collagen fibrils. The BSA group presented ACP bound to collagen with no needle-like apatite crystals. Samples kept in distilled water showed no evidence of ACP and crystal apatite. Results from rDMP1 immobilized on dentin matrix suggests that the acidic protein was able to bind to collagen fibrils and control formation of amorphous calcium phosphate and its subsequent transformation into hydroxyapatite crystals after 2 weeks.

Conclusion

These findings suggest a possible bio-inspired strategy to promote remineralization of dentin for reparative and regenerative purposes.

Keywords: dentin matrix protein 1, teeth, dentin, remineralization, electron microscopy, tissue regeneration

Introduction

Dentin, the bulk of the tooth, is a unique balance of hydroxyapatite and organic matrix that provides the tissue with specific biochemical and biomechanical properties. Dentin comprises 70% mineral (by weight), 20% organic component and 10% water. Fibrillar type I collagen accounts for 90% of the organic matrix while the remaining 10% consists of non-collagenous proteins (NCP), primarily phosphoproteins and proteoglycans. The regeneration of missing/compromised dentin structure is limited by the ability of this tissue to remodel.

Loss of tooth mineral takes place during dental caries progression or trauma. Dental caries is the most prevalent chronic disease in children; and geriatric population experience similar or higher levels of new dental caries than do school children (Griffin et al., 2004) due to increased occurrence of root caries. The demineralization of the root surface is the first step in the lesion development, and mineral dissolution will take place at a higher pH than that of enamel surfaces. The exposed organic dentin is then susceptible to degradation by proteases and its presence is believed to decrease caries progression (Hara et al., 2003). In addition, maintenance of the collagen is essential for dentin remineralization (Butler, 1995). As major component of the dentin organic matrix, fibrillar type I collagen plays a number of structural roles, such as defining compartments within the tissue that become impregnated with mineral, providing a periodic 3-dimensional template for the orderly deposition and packing of the mineral crystals, providing viscoelastic properties, and serve as a substrate for other matrix molecules either for the initiation and/or inhibition of mineralization (Beniash et al., 2000; Butler, 1995; Cheng et al., 1996; Eyre et al., 1984; Yamauchi et al., 1988).

NCP’s are believed to play essential roles in the formation of mineralized tissue; where a common characteristic feature among NCP is high content of acidic amino acids, i.e. aspartate, phosphoserine and glutamate. Among the NCP’s, dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) has been shown to be actively involved in the regulation of temporal and spatial aspects of mineral initiation (George et al., 1995; He et al., 2003; Kamiya and Takagi, 2001) by specific collagen fibril-DMP1 interaction (He and George, 2004). DMP1, a carbonate apatite nucleator, is a phosphoprotein from the SIBLING family that was first identified and isolated in dentin and later detected in bone. Recent in vitro studies have shown DMP1 to play a role in mineral formation in intra (Nudelman et al., 2011) and extra-fibrillar spaces (Beniash et al., 2011). No studies to this date have explored the use of DMP1 on remineralization of existing dentin scaffolds.

The remineralization of tooth structure using existing dentin matrix as a scaffold for mineral deposition may provide new insights for dental caries therapies and repair. Tissue mineralization is herein proposed by using recombinant DMP1 to mediate remineralization of completely demineralized human dentin. Micro-morphological changes in existing demineralized dentin following incubation with dentin matrix were accessed using electron microscopy.

Material and Methods

Substrate preparation

Five unerupted 3rd molars teeth were collected in UIC dental school of patients with 18–30 years age range. Teeth were not identifiable and determined not to be human subjects study by the Institutional Review Board from the University of Illinois at Chicago (protocol 2009-0198). Teeth were immediately placed in 0.1% thymol solution for 1 week, cleaned and kept frozen until use (approximately 2 weeks). The teeth were thawed, cleaned of adhering soft tissues, and the occlusal surfaces were ground flat with #320 grit silicon carbide abrasive paper under running water to remove part of the enamel (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA). Flattening of the occlusal surface by cusp removal enables more accurate sectioning of samples. The root portion was sectioned 1 mm below the CEJ and discarded. Teeth were sectioned into 0.5 ± 0.1 mm thick beams (n = 5 beams per tooth) in the mesio-buccal direction with a slow speed diamond wafering blade (Buehler-Series 15LC Diamond) under constant water irrigation. The sections were further trimmed using a cylindrical diamond bur (#557D, Brasseler, Savannah, GA, USA) in a high speed handpiece, to a final rectangular dimension of 0.5 mm thickness × 1.7 mm width × 6.0 mm length. Specimens were immersed in 10% phosphoric acid solution (LabChem Inc, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for a period of 5 hours and thoroughly rinsed with distilled water for 10 minutes (Bedran-Russo et al., 2011). X-rays were taken of the specimens to verify complete tissue demineralization (Cheng et al., 1996).

Composition of Dentin Scaffold

Additional demineralized dentin samples were analyzed to characterize the composition of the dentin beam scaffold.

Potential collagen solubilization during scaffold demineralization was detected on the supernatant using standard hydroxyproline assay as previously described (Bedran-Russo et al., 2011). Briefly, a 0.5 ml aliquot of the supernatant was collected and hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl at 90 °C overnight. Aliquots were mixed with water, transferred to glass tubes and adjusted to pH 7.0. A 500 µl aliquot was added to 1 ml of chloramine T buffer, followed by the addition of 1 ml of 3.15 M perchloric acid, and then 1 ml of p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde buffer was added at 60 °C for 20 min. Absorbance was measured at 557 nm in a spectrophotometer 96-well plate reader (Spectramax Plus, Molecular devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Standard curves were generated using OH–l-proline. Hydroxyproline content for each specimen was averaged from duplicate measurements.

A 100 µl aliquot of the supernatant (demineralization and rinsing solutions) were used for a micro-assay of sulfated glycosaminoglycan chains (GAGs) to evaluate removal of endogenous proteoglycans. The content of sulfated chains in the supernatant was determined using 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) solution as previously described (Barbosa et al., 2003). Briefly, the aliquot was added to working DMMB solution and vortexed to promote complete complexation of the GAGs with DMMB. The GAG–DMMB complex was separated from the soluble material, including excess DMMB. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was dissolved in a 500 µl decomplexation solution. Samples were analyzed in duplicate at 656 nm absorbance using a spectrophotometer (Spectramax Plus). Shark chondroitin sulfate sodium salt was used to determine standard curves.

Histological detection of endogenous phosphoproteins was carried out using non-specific stain for all phosphoproteins as previously reported (Rahima et al., 1988). A negative control was prepared in the same manner but treated with 1mg/ml Trypsin TPCK treated (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0.2 M ammonium bicarbonate solution (pH 7.5) to remove phosphoproteins. Dentin beam scaffolds were prepared, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 5 µm-thick sections and attached to glass slides. Following deparaffinization, sections were re-hydrated and stained with 2.5% Stain-All (Sigma-Aldrich) in propanol for 10 minutes; washed in 25% propanol solution for 10 minutes and imaged in optical microscope (Axio Observer equipped with Axiovision imaging software - Carl Zeiss Microscopes, Jena, Germany).

Remineralization strategy

Recombinant DMP1 protein without any post-translational modifications was expressed and purified as published earlier (Narayanan et al., 2003). The molecular weight of the full length rDMP1 is 60 KDa (Srinivasan et al., 1999). Briefly, the DMP1 cDNA was amplified from the rat tooth germ without the signal peptide and cloned into pGEX-4T-3 vector (Invitrogen) and expressed as Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) fusion proteins in BL21-DE3 cells. The fusion protein was then purified by binding to a glutathione sepharose column, cleaved using thrombin to remove the fusion tag and eluted through a benzamidine-sepharose column to remove thrombin (Srinivasan et al., 1999).

Nucleation of calcium phosphate polymorphs

Dentin fragments were incubated overnight with 150 µg/ml of rDMP-1 in PBS. Negative control groups were either incubated in BSA or left in distilled water. Nucleation was carried out as described previously (He et al., 2003; He and George, 2004). Briefly, after incubation, the samples were rinsed with DD water and placed into a chamber containing channels connecting two halves of an electrolyte cell, one compartment containing calcium buffer (165mM NaCl, 10mM HEPES, 2.5mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and the other phosphate buffer (165mM NaCl, 10mM HEPES KH2PO4 pH 7.4). A small electric current of 1mA was passed through the system to facilitate even distribution of the ions on the specimen. The buffers were changed regularly to maintain a constant pH. At the end of 7 and 14 days the specimens were removed, washed with distilled water and prepared for imaging analyses.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Specimens were fixed in 2.5% paraformaldehyde/glutaraldehyde in 0.1M Sodium cacodylate for 3 days. Specimens were rinsed and dehydrated in increasing concentration of ethanol (50% - 20 min, 75% - 20 min, 90% - 30 min, 95% - twice – 30 min, 100% twice- 60 min). Specimens were infiltration with LR White resin (Electron microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Specimens were sectioned into 70nm thick section using a diamond knife attached to an ultra-microtome (Ultracut UCT, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL). Sections were placed on copper grids and post-stained with uranyl acetate for 1 minute. Sections were imaged and analyzed on TEM (JEM-1220, JEOL, Peabody, MA) at 80Kv. Additional unstained sections were placed on carbon coated grids for selected area electron diffraction (SAED) and atomic resolution imaging using a TEM (JEM-3010, JEOL) at 300Kv.

Field-emission electron microscopy (FE-SEM)

Specimens were dehydrated in increasing concentration of ethanol (50% - 20 min, 75% - 20 min, 90% - 30 min, 95% - twice – 30 min, 100% twice- 60 min) and immediately fixed using Hexamethyldisilazane for 20 minutes. Specimens were mounted in aluminum stubs using carbon tape, gold sputter coated and surface was analyzed on FE-SEM (Jeol JSM-6320F) at 5Kv.

Results

Dentin scaffold composition

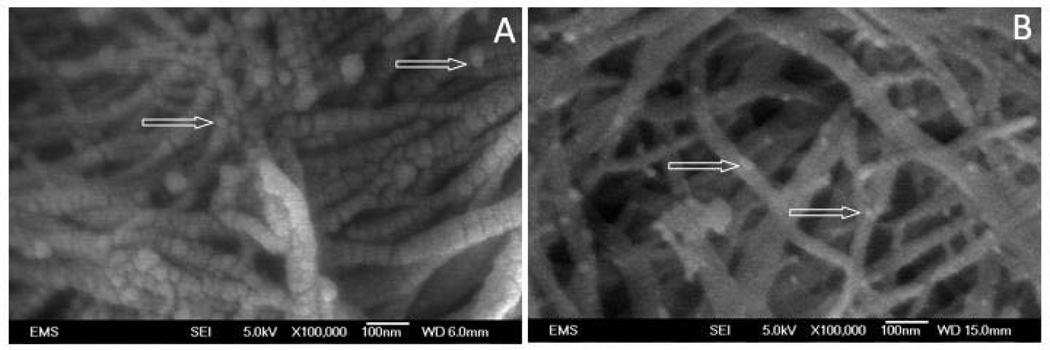

The use of 10% phosphoric acid solution did not solubilize collagen, as determined by no detection of hydroxyproline in the demineralization and rinsing solution. GAGs chains were not detected in the phosphoric acid solution following demineralization and small concentration was detected in rinsing solution (6.05 ug/ml), which indicates that great amount of PG remained in the dentin scaffold following demineralization. Light microscopy images of crown dentin matrix stained for all phosphoproteins show the presence of endogenous phosphoproteins, with dense and homogenous distribution throughout the scaffold (Figure 1). Reduced staining was observed in trypsin treated specimens (negative control) ruling out false positive (figure not shown).

Figure 1.

Representative light microscopy image of section of dentin matrix scaffold stained for all phosphoproteins. A - Abundant presence of phosphoproteins is clearly detected by intense purple staining of inter-tubular dentin following demineralization, indicating significant presence of endogenous phosphoproteins. B - Negative control included to rule out background staining of dentin scaffold. Removal of phosphoproteins by trypsin digestion indicated by weak staining confirms presence of endogenous proteins in dentin scaffold. Magnification: 30×

Electron microscopy

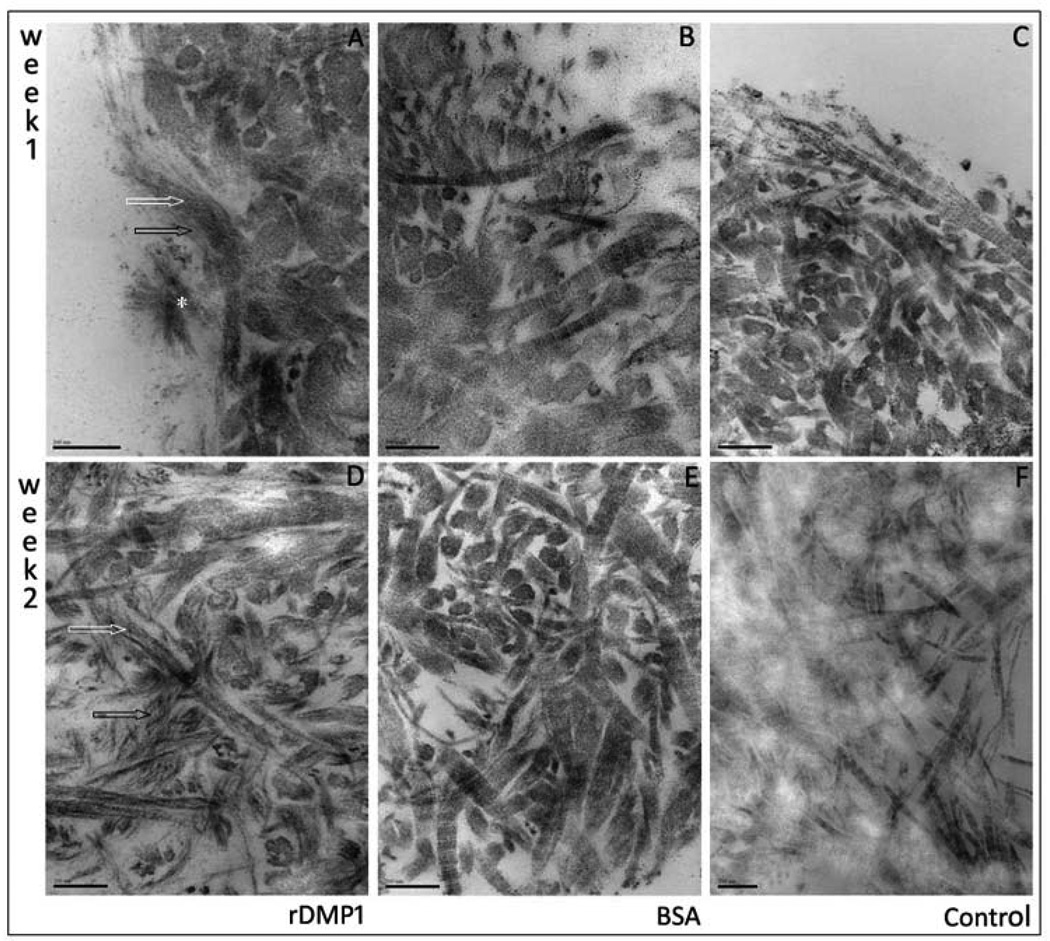

After 1 week remineralization, DMP1 treated samples presented amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) precursors and needle-like shaped hydroxyapatite crystals surrounding collagen fibrils (Figure 2). Limited visualization of collagen banding and presence of fibrillar mineral deposition was observed when compared to control and BSE groups (Figure 2). Dentin slabs incubated in distilled water and BSA showed no evidence of ACP and crystal apatite; intense collagen structure could be visualized with well defined banding.

Figure 2.

Representative transmission electron microscopy images of dentin matrix scaffold after 1 and 2 week nucleation of calcium and phosphate polymorphs in presence of physiological concentrations of calcium and phosphate. One week remineralization: A – rDMP1 incubated samples show inter-fibrillar (black arrow) and fibrillar (white arrow) needle like crystals. Asterisk indicates large nucleation site on scaffold surface with needle like apatite crystal. BSA (B) and distilled arrow (C) show no evidence of remineralization or ACP precursors. Two week remineralization: D – rDMP1 resulted in great increase in apatite crystal formation that affected visualization of collagen banding; No crystal formation could be visualized in BSA (E) and distilled water (F).

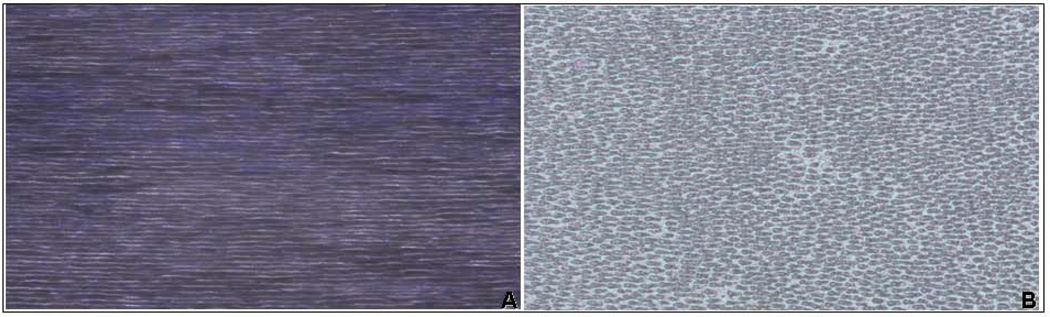

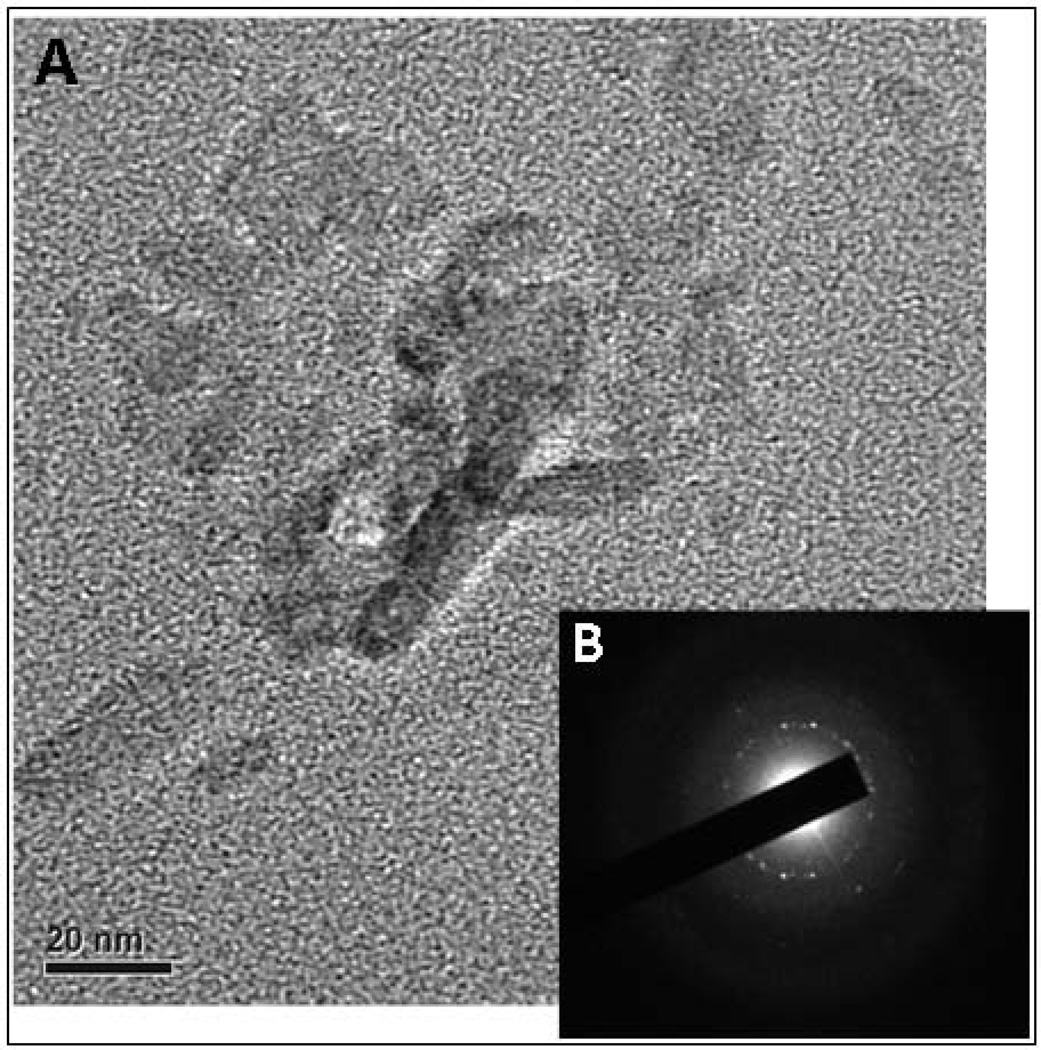

After 2 weeks, increased fibrillar and inter-fibrillar mineral deposition was evident on the rDMP1 treated samples which impaired visualization of collagen banding in most sites (Figure 2). Surface imaging using field-emission SEM showed increased ACP precursors observed on BSA group with no apatite crystals formation (Figure 3). Samples kept in distilled water showed no evidence of ACP or crystal apatite formation (Figure 2); intense collagen structure displaying well defined banding and clear inter-fibrillar spaces were shown in this group. SAED of unstained dentin section remineralized for 2 week confirms the microcrystalline nature of the deposits found in the dentin sections (Figure 4). Atomic resolution TEM images show the stacking pattern of crystal formation (image not shown). It is important to note that the visualization of collagen banding in all sections is due to uranyl acetate staining and does not indicate presence of intra-fibrillar mineralization.

Figure 3.

Representative field emission scanning electron microscopy images of dentin matrix scaffold after 2 week nucleation of calcium and phosphate polymorphs in presence of physiological concentrations of calcium and phosphate: A - rDMP1 clearly shows amorphous calcium phosphate precursors and mineral deposition over collagen fibrils; B – BSA incubation show presence of various amorphous calcium phosphate precursors with no apparent mineral deposition in collagen fibrils. (White arrow: amorphous calcium phosphate precursors).

Figure 4.

(A) Transmission electron microscopy images of unstained dentin matrix incubated with rDMP-1 after 2 week nucleation of calcium and phosphate polymorphs. Presence of electron-dense area indicates presence of mineralization. (B) Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) analysis confirms the microcrystalline nature of the deposits impregnating the type I dentin collagen.

Discussion

The present study is a proof-of-principal that the use of a recombinant non-phosphorylated DMP1 (rDMP1), can mediate initial apatite crystal formation and deposition on completely demineralized dentin scaffold. Novel approaches for dentin remineralization has intensified in the past decade due to increased demand for innovative and effective therapies for reparative and regenerative dentistry. Traditional therapies using fluoride for caries control have shown to be more challenging in root surfaces (Heilman et al., 1997) as opposed to enamel due to the complex collagen scaffold based remineralization. Use of bioactive materials such as amorphous calcium phosphate, MTA and calcium phosphate are promising but lack evidence of assisted mineral deposition. Current knowledge in the regulation of dentin mineralization process has inspired the use of phosphoprotein analogs such as polyvinylphosphonic acid-polyacrylic acid (Tay and Pashley, 2008) and sodium trimetaphosphate (Liu et al., 2011) to guide remineralization of dentin that lost mineral during restorative procedure or carious progression.

Recombinant DMP1 collagen has been previously shown to initiate mineralization in insoluble collagen (He & George, 2004), which can be further accelerated by introduction of poly-l-aspartic acid (Nudelman et al., 2011). The present study showed that mediated mineral deposition was possible in demineralized human dentin under physiological concentrations of calcium and phosphate. Imaging analysis of demineralized dentin matrix clearly shows needle like apatite crystals in the collagen inter-fibrillar spaces but intra-fibrillar mineralization is unclear.. Although not measured, it is evident that collagen fibrils are thicker in rDMP1 exposed specimens which is an indicator of fibrillar mineralization (Zeiger et al., 2011). The incubation of demineralized dentin matrix with rDMP1 indicates that the acidic protein was able to bind to collagen fibrils and mediate formation and regulation of amorphous calcium phosphate into hydroxyapatite crystals. Mineralization of DMP1 treated samples was evident after 1 week and more remarkable after 2 weeks. After 2 weeks, limited collagen banding was observed in several areas due to apatite deposition (Figure 2). Amorphous calcium phosphate precursors in BSA treated samples did not further develop into apatite crystals (Figure 2 and 3). BSA has been shown to induce amorphous calcium phosphate deposition. Interestingly no precursors were observed in samples kept in distilled water, regardless of the presence of endogenous phosphoproteins.

Following dentin demineralization, intense phosphoprotein stain was observed in inter-tubular dentin, which indicates strong binding affinity with collagen. Phosphoproteins have been localized in inter-tubular dentin of rodent teeth (Rahima et al., 1988) and DMP1 immunolocalized in rodents (Aguiar and Arana-Chavez, 2011; Massa et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2004) and permanent human molars (Orsini et al., 2008). Interestingly, endogenous phosphoproteins remaining in the dentin matrix scaffold (Figure 3) were not able to initiate mineral formation and deposition (control group) after 2 weeks. It is possible that conformational changes following demineralization could have affected the calcium binding affinity of the phosphoproteins that may have impaired their ability to initiate mineralization. Longer remineralization period is needed to further characterize remineralization ability of endogenous phosphoproteins remaining in the tissue.

Phosphoric acid is a common dentin conditioner used during restorative procedures and was chosen in this study to expedite demineralization. The concentration and application time have been extensively used for the evaluation of dentin biomechanical and biochemical characterization (Bedran-Russo et al., 2011; Bedran-Russo et al., 2008). The demineralization protocol did not solubilize collagen as verified by HYP analysis of the supernatant. Higher concentrations of phosphoric acid applied for a shorter period of time has been shown to not affect collagen biochemistry (Ritter et al., 2001). Although previous study reported reduced GAGs immunoreactivity in dentinal tubules following treatment with high concentration of phosphoric acid solutions (Oyarzun et al., 2000); the majority of proteoglycans seem to remain in the demineralized scaffold. Higher quantity of GAGs detected in the digested scaffold (data not shown) and histology of GAGs (data not shown) support previous finding of limited PGs removal by 10% phosphoric acid (Bedran-Russo et al., 2011).

The presence of remineralization was limited to about 15 microns within the dentin scaffolds coated with rDMP1. The average diameter of a protein with size ranging from 50KDa to 100KDa is between 2.4 and 3.05nm. (Erickson, 2009). Considering that interfibrillar spaces range between 50nm to greater than 1um, the rDMP1 molecule would theoretically have space to infiltrate. However, glycosaminoglycans chains in proteoglycans are highly negatively charged and function as a barrier for molecule diffusion through the matrix (Torzilli et al., 1997). Insufficient rDMP1 or limited penetration within the scaffold could have affected the remineralization at deeper sites within the scaffold. Enhancing penetration of rDMP1 needs to be further investigated.

In conclusion, the qualitative imaging analyses show that rDMP1 mediates remineralization at the outer layer of demineralized dentin scaffolds. The present findings suggest a possible bioinspired strategy to promote remineralization of dentin for application in preventive and reparative/regenerative dentistry.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for Dr. Carina Castellan’s assistance on the dentin specimen preparation. This research was supported by research grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health (DE017740).

Glossary

- DMP

Dentin matrix protein 1

- NCPs

non-collagenous proteins

- DMMB

1,9-dimethylmethylene blue

- GAGs

glycosaminoglycans chains

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors disclose no actual or potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aguiar MC, Arana-Chavez VE. Immunocytochemical detection of dentine matrix protein 1 in experimentally induced reactionary and reparative dentine in rat incisors. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;55(3):210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa I, Garcia S, Barbier-Chassefiere V, Caruelle JP, Martelly I, Papy-Garcia D. Improved and simple micro assay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans quantification in biological extracts and its use in skin and muscle tissue studies. Glycobiology. 2003;13(9):647–653. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedran-Russo AK, Castellan CS, Shinohara MS, Hassan L, Antunes A. Characterization of biomodified dentin matrices for potential preventive and reparative therapies. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(4):1735–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedran-Russo AK, Pashley DH, Agee K, Drummond JL, Miescke KJ. Changes in stiffness of demineralized dentin following application of collagen crosslinkers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;86B(2):330–334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E, Deshpande AS, Fang PA, Lieb NS, Zhang X, Sfeir CS. Possible role of DMP1 in dentin mineralization. J Struct Biol. 2011;174(1):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E, Traub W, Veis A, Weiner S. A transmission electron microscope study using vitrified ice sections of predentin: structural changes in the dentin collagenous matrix prior to mineralization. J Struct Biol. 2000;132(3):212–225. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler WT. Dentin matrix proteins and dentinogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;33(1–3):59–65. doi: 10.3109/03008209509016983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Caterson B, Neame PJ, Lester GE, Yamauchi M. Differential distribution of lumican and fibromodulin in tooth cementum. Connect Tissue Res. 1996;34(2):87–96. doi: 10.3109/03008209609021494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson HP. Size and shape of protein molecules at the nanometer level determined by sedimentation, gel filtration, and electron microscopy. Biol Proced Online. 2009;11:32–51. doi: 10.1007/s12575-009-9008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre DR, Koob TJ, Van Ness KP. Quantitation of hydroxypyridinium crosslinks in collagen by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1984;137(2):380–388. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Silberstein R, Veis A. In situ hybridization shows Dmp1 (AG1) to be a developmentally regulated dentin-specific protein produced by mature odontoblasts. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;33(1–3):67–72. doi: 10.3109/03008209509016984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SO, Griffin PM, Swann JL, Zlobin N. Estimating rates of new root caries in older adults. J Dent Res. 2004;83(8):634–638. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara AT, Queiroz CS, Paes Leme AF, Serra MC, Cury JA. Caries progression and inhibition in human and bovine root dentine in situ. Caries Res. 2003;37(5):339–344. doi: 10.1159/000072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Dahl T, Veis A, George A. Nucleation of apatite crystals in vitro by self-assembled dentin matrix protein 1. Nat Mater. 2003;2(8):552–558. doi: 10.1038/nmat945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, George A. Dentin matrix protein 1 immobilized on type I collagen fibrils facilitates apatite deposition in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(12):11649–11656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilman JR, Jordan TH, Warwick R, Wefel JS. Remineralization of root surfaces demineralized in solutions of differing fluoride levels. Caries Res. 1997;31(6):423–428. doi: 10.1159/000262433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya N, Takagi M. Differential expression of dentin matrix protein 1, type I collagen and osteocalcin genes in rat developing mandibular bone. Histochem J. 2001;33(9–10):545–552. doi: 10.1023/a:1014955925339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li N, Qi Y, Niu LN, Elshafiy S, Mao J, Breschi L, Pashley DH, Tay FR. The use of sodium trimetaphosphate as a biomimetic analog of matrix phosphoproteins for remineralization of artificial caries-like dentin. Dent Mater. 2011;27(5):465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa LF, Ramachandran A, George A, Arana-Chavez VE. Developmental appearance of dentin matrix protein 1 during the early dentinogenesis in rat molars as identified by high-resolution immunocytochemistry. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;124(3–4):197–205. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan K, Ramachandran A, Hao J, He G, Park KW, Cho M, George A. Dual functional roles of dentin matrix protein 1. Implications in biomineralization and gene transcription by activation of intracellular Ca2+ store. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):17500–17508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman F, Pieterse K, George A, Bomans PH, Friedrich H, Brylka LJ, Hilbers PA, de With G, Sommerdijk NA. The role of collagen in bone apatite formation in the presence of hydroxyapatite nucleation inhibitors. Nat Mater. 2011;9(12):1004–1009. doi: 10.1038/nmat2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini G, Ruggeri A, Mazzoni A, Nato F, Falconi M, Putignano A, Di Lenarda R, Nanci A, Breschi L. Immunohistochemical localization of dentin matrix protein 1 in human dentin. Eur J Histochem. 2008;52(4):215–220. doi: 10.4081/1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzun A, Rathkamp H, Dreyer E. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evaluation of the effects of phosphoric acid etching on dentin proteoglycans. Eur J Oral Sci. 2000;108(6):546–554. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahima M, Tsay TG, Andujar M, Veis A. Localization of phosphophoryn in rat incisor dentin using immunocytochemical techniques. J Histochem Cytochem. 1988;36(2):153–157. doi: 10.1177/36.2.3335773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter AV, Swift EJ, Jr, Yamauchi M. Effects of phosphoric acid and glutaraldehyde-HEMA on dentin collagen. Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109(5):348–353. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Chen B, Gorski JP, George A. Recombinant expression and characterization of dentin matrix protein 1. Connect Tissue Res. 1999;40(4):251–258. doi: 10.3109/03008209909000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay FR, Pashley DH. Guided tissue remineralisation of partially demineralised human dentine. Biomaterials. 2008;29(8):1127–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torzilli PA, Arduino JM, Gregory JD, Bansal M. Effect of proteoglycan removal on solute mobility in articular cartilage. J Biomech. 1997;30(9):895–902. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi M, Woodley DT, Mechanic GL. Aging and cross-linking of skin collagen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;152(2):898–903. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, MacDougall M, Zhang S, Xie Y, Zhang J, Li Z, Lu Y, Mishina Y, Feng JQ. Deletion of dentin matrix protein-1 leads to a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization, and expanded cavities of pulp and root canal during postnatal tooth development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):19141–19148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiger DN, Miles WC, Eidelman N, Lin-Gibson S. Cooperative calcium phosphate nucleation within collagen fibrils. Langmuir. 2011;27(13):8263–8268. doi: 10.1021/la201361e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]